This blog was written by Olivia Dorothy, Upper Mississippi River Basin Director, American Rivers & Brad Gordon, 2017-2019 American Rivers Lapham Fellow, currently the Southern Minnesota Program Manager at Great River Greening

In the Midwest, nitrogen and phosphorus pollution from farms is a persistent problem. In excess, these nutrients, which plants need to thrive, can cause toxic conditions in lakes, rivers, streams and aquifers. Too much nitrogen in a water supply can interrupt the delivery of oxygen to your body’s cells, which can lead to death, particularly in infants. Both phosphorus and nitrogen pollution can also contribute to toxic algae blooms in lakes, rivers and estuaries. The over-production of blue-green algae can suck all the oxygen out of the water column and cause massive fish kills. Some types of algae can also produce a toxin, microcystin, that can cause a range of stomach problems and liver failure.

In 2014, a large toxic algae bloom in Lake Erie caused 400,000 people in Toledo to lose access to clean drinking water.i Nutrient pollution-fueled “dead zones” along the U.S. coasts costs our seafood and tourism industries at least $82 million a year.ii Even communities along hundreds of miles of the Ohio River had to issue drinking water advisories in 2019 due to drought-like conditions that helped the toxic algae flourish.iii

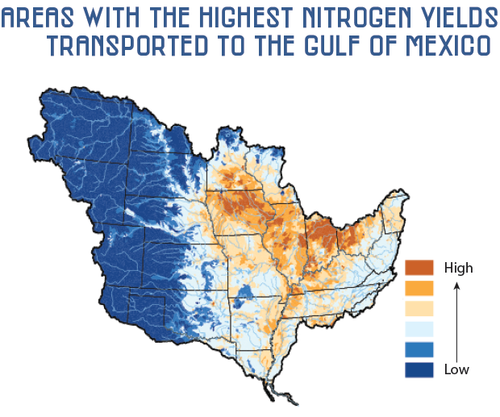

While nutrient pollution is a global problem, it is particularly prevalent in the Upper Midwest Corn Belt. Corn requires massive amounts of fertilizer that farmers deliver in the raw, inorganic forms. The inorganic forms of fertilizer are more water soluble, meaning the plant can take up the nutrients faster. But it also means that they are easily washed downstream during precipitation events, where they cause problems for aquatic ecosystems and drinking water supplies.

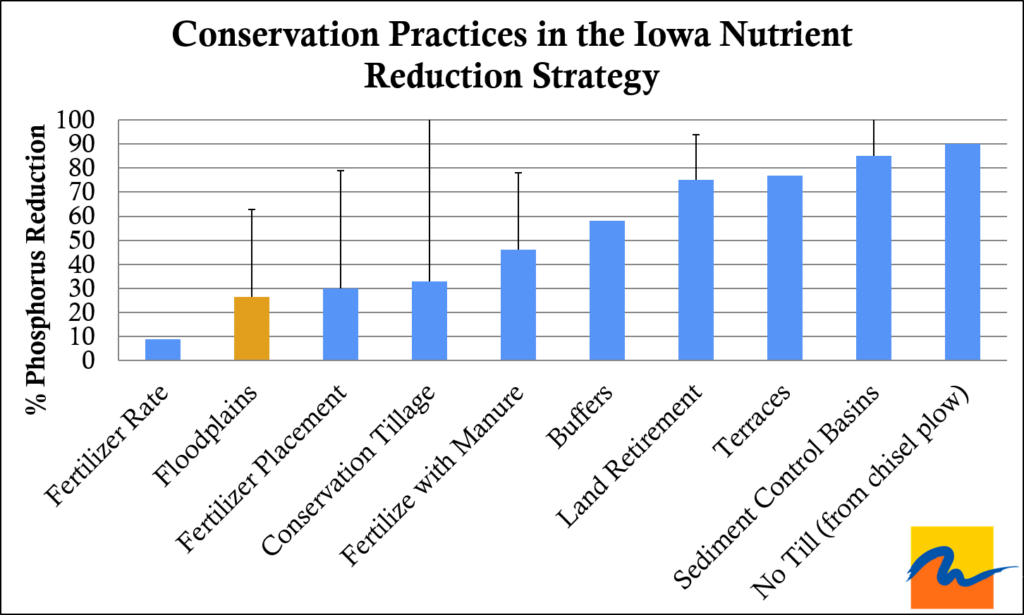

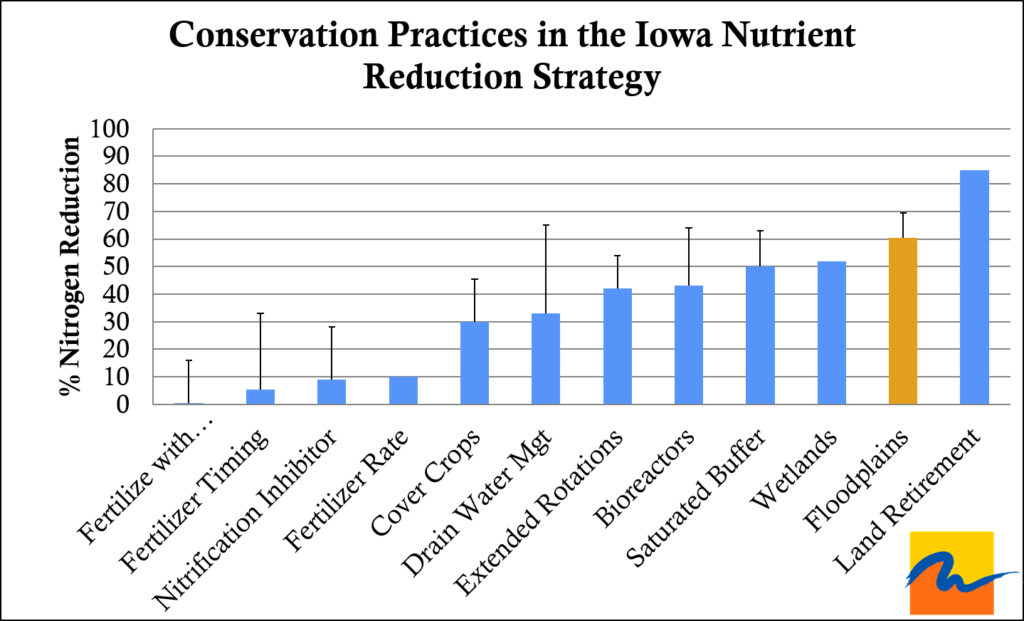

To respond to this growing environmental crisis, Mississippi River Basin states have developed nutrient reduction strategies to target investments in voluntary on-farm conservation and land management practices that will reduce nutrient pollution. While several strategies call for more enrollment of land into conservation easements and the establishment of wetlands, most states have overlooked floodplain restoration as an important tool to help reduce nutrient pollution.

In addition to floodplain restoration’s potential to remove nutrient pollution from rivers, floodplain restoration has the benefit of providing many additional ecosystem services for communities. Reconnecting and restoring floodplains can help convey floodwater away from people and critical infrastructure, provide habitat for native plants and animals, recharge groundwater supplies, spur economic developing and property tax revenues, and increase the quality of life for communities by providing natural areas for recreation and relaxation.v

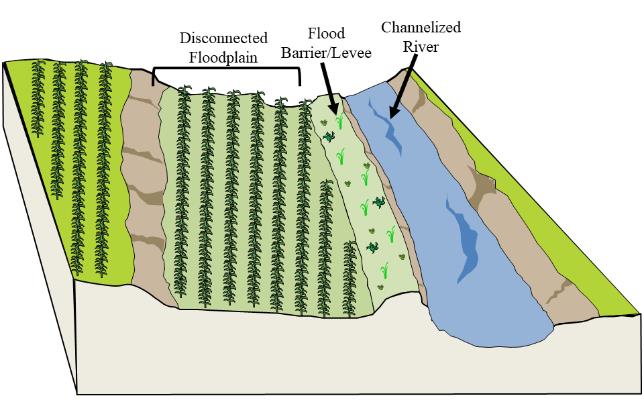

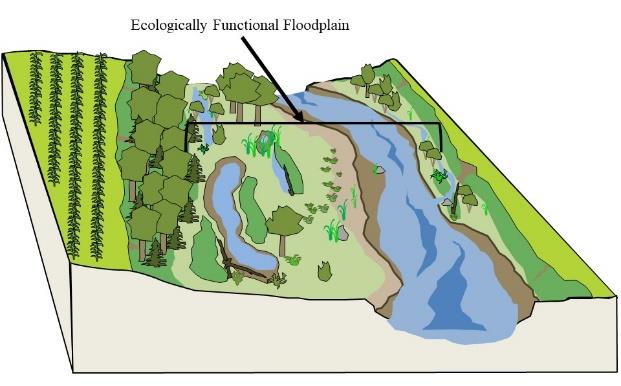

This is a depiction of a disconnected and non-functional versus an ecologically functional floodplain. Ecologically functional floodplains flood regularly without constructed barriers or incised main channels that prevent water from entering the floodplain during high-flow events. They are also capable of supporting plant and animal communities native to that region.

To better understand the nutrient removal potential of ecologically healthy floodplains, American Rivers conducted a literature review of over 200 studies from North America and Europe, 40 of which contained relevant data for our study. We found that floodplain reconnection and ecosystem restoration has the potential to permanently remove both nitrogen and phosphorus from the water column.

Based on literature reviewed, The mean removal of nitrate-N (NO3–-N), the primary form of N in floodplain studies, was 200 (SD = 198) kg-N ha-1 year-1, and of total or particulate P was 21.0 (SD = 31.4) kg-P ha-1 year-1.

The literature review also found that nutrient retention potential of floodplains is likely based on a few key design features. These include:

- Engineering the floodplain landscape to slow the water down. Although more flow across the floodplain could lead to a greater total mass of nutrients removed, the floodplain will lose effectiveness (the percent removal) as flow rates increase.

- Incorporating a permanently inundated wetland in the floodplain area. Permanent inundations with shallow or gently graded banks provide the most aquatic-terrestrial fringe habitat that is ideal for bacteria that remove nitrogen. Ephemeral wetlands that dry out completely and ponds with steep banks have limited nitrogen removal potential.

- Ensuring geomorphic diversity across the floodplain. Incorporating dips and swells into the floodplain landscape will help slow the water down so it can drop out phosphorus laden soil. Most soil is consolidated and buried on the floodplain and will not be released over the long-term.

- Restoring dense vegetation in the floodplain. Vegetation improves nutrient removal by providing organic matter for denitrifying microbes and slows water flow for better sedimentation and accretion.

- Harvesting vegetation from floodplains where feasible. This may aid in phosphorus removal, but caution should be taken due to the unknown impact on native plant communities.

- Restoring floodplains along waterways with higher concentrations of nutrients. Floodplains can permanently remove large amounts of nutrients as long as the water is slowed down to maximize nutrient removal.

Floodplain restoration should be used more in the Midwest as a tool to remove nutrient pollution. Too often, floodplain development projects overlook restoration as an option. Ecosystem restoration is often perceived as having a low or negative return on investment. Home buyouts in floodplains might allow the river to be reconnected, but the ecosystem functionality is not restored – the land is usually maintained as paved or turfed “open space.” Where ecosystem restoration projects do take place in floodplains, reconnection to the river is rare as funding sources usually prohibit restoration projects in frequently flooded lands.

Our publication adds to a growing body of evidence that floodplain restoration is an essential tool to improve water quality and build more resilient communities.

Read the full paper here.

Citation: Gordon, Brad, Olivia Dorothy, Christian Lenhart. 2020. Nutrient retention in ecologically functional floodplains: A review. Water, 12, 2762.

Just like the seasons, rivers change, and change is hope (a particularly valuable commodity nowadays). While summer and spring tend to receive the most fanfare, we think each season on the river holds its own special beauty and adventures. These are a few of our favorite things about getting out on the river, no matter the season:

More than any other season, a river in spring is a messenger of hope. Their floods nourish the ground with fresh soil. They invite us to join in the songs and dances of animals, to do something new and bold. Watching life sprout up after a long winter can sometimes be all it takes to regain the strength inside us to keep pushing for a better world.

Spring also brings the start of National River Cleanup® season! Across the country, people volunteering for National River Cleanup® commit their time and energy to keeping our rivers clean for all to enjoy. We are grateful to our sponsors for helping to inspire their communities to join us – in 2019 Cascade Blonde pledged to work in their communities along side National River Cleanup and local river organizations to keep 100,000 pounds of trash from waterways. There’s no better (or more fun) way to see the power a single person can have within a community than joining a river clean up.

Summer on the river gets all the attention, with good reason! When the thermometer starts creeping up, nothing beats hitting the gravel road, rolling down the window and making your way to the river. It’s not just about beating the heat and escaping to bask in the cooler temperatures rivers provide. From serene paddles to whitewater action; from lazy floats to fly-fishing; from riverside hikes to family picnics — summer rivers have it all.

Honestly, the only hard part is, no matter how excited we are for fall, it still hurts to see the treasured days of summer slip through our fingers. Oh, and toxic algae.

Ah fall: when every leaf is a flower and every river a painting. Every autumn, river and stream valleys around the country erupt with beautiful fall colors and the chorus of migrating birds making their way south. Finally, the perfect opportunity to flex those photography skills!

It’s also the time for bundling up in flannels and hiking boots. Finally, you can explore and camp without every insect in a five mile radius begging to make your acquaintance. The change in humidity, that crisp air we all love, also means hiking doesn’t have to drench you in a layer of your own perspiration. The same is true for heading to the river to help clean up plastics and litter. You’ll be surprised how long you can stay out there on a cool fall day with a thermos of something warm.

When the days grow short, some of us prefer hibernating. But for the winter river warriors out there, new sights and adventures await. Where it gets cold enough, ice crystals turn ordinarily beautiful rivers into extraordinary exquisite rivers and skiing makes their trails even more accessible.

Photo by Lee Cohen

Even in the middle of winter, water and rivers are the ultimate source of life. If you’re lucky, you might catch a peek at some of the amazing animals that take on the cold temperatures, harsh weather, and limited food supplies in their own special way. Plus, we all know there’s no better feeling than really earning that cozy cup of hot cocoa after a day out in the cold.

If nothing else, the winter gives us the opportunity to mark the end of another year with the people and rivers we love.

Let’s be real:

Rivers are perfect every second, minute and day, no matter the season!

Whats your favorite river season?

When two tribes, two states and Warren Buffett step up and commit to the world’s biggest dam removal project – it’s a big deal.

That’s what happened last week, when the Karuk and Yurok tribes, California Governor Newsom, Oregon Governor Brown, the Klamath River Renewal Corporation and PacifiCorp, a subsidiary of Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway, announced an agreement that advances the removal of four dams on the Klamath River.

This river restoration has taken decades of effort by the tribes, American Rivers and many partners. We are thrilled to reach this milestone and we’re going to keep at it until we reach the finish line – and see this river flowing free.

We hope this ad, running in USA Today and the Salem Statesman Journal, expresses our deep gratitude to Governor Brown, Governor Newsom, the Karuk and Yurok tribes, PacifiCorp and the KRRC.

The press conference on November 17 was moving, with everyone speaking from the heart.

Here are some highlights:

Yurok Chairman Joseph L. James –

“This dam removal is more than just a concrete project coming down. It’s a new day and a new era for tribes.”

“We are connected with our heart and prayers to these creeks, lands and animals, and our way of life will thrive with these dams coming out.”

“It is our duty and our oath to bring balance to the river.”

“The effort to heal the Klamath River is an expression of tribal sovereignty, a fulfillment of Indian rights and a restoration of justice. It benefits our neighbors up and down the West coast. The effort to heal the Klamath River is who we are. We walk it, we live it, we pray it.”

Karuk Chairman Russell “Buster” Attebery –

“The Karuk people have been dependent on salmon, steelhead, sturgeon, eels since the beginning of time.”

“My worst day as chairman is when I said there were no fish available for our tribal members, our elders, our children…I’m looking forward very much to having the best day as chairman of the Karuk Tribe when I can say we have restored those fish and we can enjoy those bonding times with our children, when we can go to the river and put the food on the table together.”

“We hope it is a benefit to everyone. Everyone who comes into contact with the Klamath River. Everyone who lives close to the river who wants to vacation here, the farmers and irrigators who live in the upper basin. We want to make sure there is enough water for everybody. Working together, we can do that.”

Oregon Governor Kate Brown –

“What we are doing is more than just signing a legal document. We are taking an incredibly important step forward on the path toward restorative justice for the people of the Klamath basin and toward restoring the health of the river as well as everyone and everything that depends on it.”

“The agreement is about far more than the removal of four dams. It’s a step toward righting historic injustices while also putting these lands and waters on a path to the future that everyone can share.”

“In Oregon, our Klamath tribes remember a time when their livelihoods were supported by clean, healthy and vibrant waters. It is that vision, that promise that we are working toward restoring for generations to come.”

California Governor Gavin Newsom –

“One of the wonderful things about the history of this endeavor is the dialectic between tribal nations, tribal elders… we simply wouldn’t be here without you and your leadership, the council’s leadership, tribal elders’ leadership.”

“Some of my greatest memories are going up to this river with my father…passion doesn’t begin to describe his environmental stewardship, and he really made that indelible in my life … It’s in that generational mindset that I’m here…”

“In a time that we’re filled with so much cynicism, so much anxiety, so much negativity, that we’re here on the precipice of the largest river restoration project in the history of this country…what an extraordinary moment.”

Greg Abel, Berkshire Hathaway –

“I am pleased today to restate PacifiCorp and Berkshire Hathaway’s commitment to the agreement…including the removal of the dams and more important, the restoration of the river and the lives of the tribal communities.”

“We know the issue of removal of these dams is of incredible importance to the tribes and is a matter of social, economic and racial justice.”

Meadows in the Sierra Nevada mountains are critical components of our rivers and watersheds. They are places of beauty, diversity, and important habitat for many native animals, birds, and plants. Meadows also contain large quantities of carbon in their rich, deep soils. While it has been known for some time that meadows harbor large quantities of soil carbon, whether meadow soils are gaining or losing carbon and how this might be related to meadow condition, has been unclear.

Research published in the scientific journal Ecosystems revealed that meadows with wetland plant communities and dense root mats were large net carbon sinks, meaning they removed carbon from the atmosphere. In fact, per acre, the amount of carbon captured in these meadows was similar to rates measured in tropical rainforests. On the other hand, meadows with more bare ground and plant communities associated with drier soil released large amounts of carbon from the soil to the atmosphere. In the long-term, such changes to the large soil carbon stocks in meadows could add up. And unlike in forests, where most carbon is sequestered in wood aboveground, the change in carbon in meadows is belowground. This means meadow soil carbon is less vulnerable to disturbances such as wildfire and may persist in the ecosystem for longer than aboveground carbon. These findings will help us identify meadows to protect to maintain soil carbon gains and meadows in need of restoration to prevent additional losses of soil carbon to the atmosphere.

This Sierra wide study was born through a collaboration between CalTrout, American Rivers, Stillwater Sciences, University of Reno, UC Merced, Plumas Corp, Truckee River Watershed Council, Sierra Foothill Conservancy and South Yuba River Citizen’s League. This collaboration, that eventually grew into the Sierra Meadows Partnership, has demonstrated that meadows throughout the region are both gaining and losing carbon at high rates. Capture and storage of carbon in soil is a natural way to reduce carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere and combat climate change. However, human activities can disrupt natural processes and lead to the loss of soil carbon to the atmosphere. These results suggest that meadow management may either contribute to climate change or mitigate the harmful effects of increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide. The study is aimed at arming restoration practitioners with information to help make good management decisions.

“It was fantastic to see the amount of dedicated hard work done by literally dozens of people to collect and analyze reliable and consistent samples throughout the Sierra over a three-year period. UNR graduate student Cody Reed added the essential missing parts not included in our original proposal, making it possible to gain a much better understanding of how much carbon is actually going into or out of the soil with healthy versus degraded meadows. The results have been very nicely articulated by Cody in this article,” said Amy Merrill of American Rivers, also a coauthor of the study. Amy helped initiate and the orchestrate this project while at Stillwater Sciences and now, at American Rivers, is leading the second half of this project to determine if these changes in carbon sequestration can be observed once the degraded meadows are restored, and if there is a way to predict those changes through modeling.

Cody Reed, a doctoral student in Ben Sullivan’s lab at the University of Nevada, Reno, took the lead on the first half of the funded project. Cody added several important aspects to the research design, including an isotope tracing study to better elucidate the flow of carbon through the plant-soil system. Steve Hart at the University of California Merced provided critical scientific insights and has had several undergraduate and graduate students engage in this project. Field soil, vegetation, and gas sample collection was orchestrated by Stillwater Sciences and UNR, with the eight partner organizations each engaged in data collection, and Stillwater Sciences and the two Universities performing laboratory analyses.

“Meadows are hotspots of diversity in the forested landscape of the Sierra Nevada. It is fantastic to see these numbers, demonstrating that healthy meadows provide all kinds of benefits, from habitat for diverse plant and animal species, to improved downstream summer flows and water quality, and now to super impressive rates of carbon sequestration. We now know, like many native American tribes have known for many centuries, that these are places to treasure, restore, and protect.”

One of my favorite quotes is from Leonardo da Vinci, “In rivers, the water that you touch is the last of what has passed and the first of that which comes; so with present time.” Elections are like rivers, framed by what has happened in the past and full of possibility for the future. This year’s election is no exception.

Now that it appears that Joe Biden is our President-elect, American Rivers is ready to work with President Biden, Vice President Harris, and their administration to repair the substantial damage to rivers and clean water done by the Trump administration over the past four years and, going forward, make real progress in protecting and restoring rivers and conserving clean water. We’ve identified five priorities for the Biden-Harris administration and Congress in our 2021 Blueprint for Action:

- Invest in rivers and clean water to recover from COVID-19

- Reverse regulatory rollbacks and restore strong, effective federal protection for rivers and clean water

- Improve protection and management of the nation’s floodplains

- Launch a national initiative to prioritize and fund dam removals

- Increase protection of Wild and Scenic rivers

While some of these priorities can be accomplished by the new administration itself, many will require congressional action. Regardless of which party controls the Senate (and we may not know until January following runoff elections in Georgia), Congress will continue to be closely divided, making bipartisanship even more important.

The need for bipartisanship was amply demonstrated in this year’s election when voters on Colorado’s Western Slope voted overwhelmingly to pass ballot measure 7A, raising property taxes to provide nearly $5 million annually for protecting water supplies for farmers and ranchers, drinking water for Western Slope communities, and rivers for fish, wildlife, and recreation. American Rivers joined with a bipartisan group of stakeholders to lead the campaign for 7A. As Colorado River District general manager Andy Mueller said in The Aspen Times, the results prove that water “was the one issue that’s not partisan, that was about uniting a very politically diverse region. Everybody is so sick of the nasty, divisive, partisan politics. People with Trump signs and Biden signs voted for the same thing.”

Our slogan at American Rivers, Rivers Connect Us, is worth remembering as a newly elected President Biden and Congress tackle the nation’s pressing issues in the next four years. While there is a Republican River that flows through Nebraska and Kansas, and a Democrat Creek in Colorado, support for rivers and clean water should not be a partisan issue.

If you’re like me, you probably have at least a dozen different river stories in the back of your mind.

Some conjure memories of family, friends and the shared experiences on the river, while others might evoke visceral memories of waiting out an hours-long summer afternoon storm, drenched and freezing cold. Your river story might include reeling in the fish of a lifetime, or a long swim through a class five rapid. Maybe there’s a special river you were married on, or another on which you spent your honeymoon, or perhaps you spread the ashes of a loved one on yet another river that holds important meaning.

This week, my river story didn’t involve one specific river, but concerned the protection of many rivers that have shaped my life over the last decade. After the years of outreach I have conducted to Montanans from all walks of life, I know that I’m not alone in harboring a cadre of rivers stories. There are generations upon generations of stories like mine intertwined with the rivers that hold them. And this week, Senator Jon Tester (D-MT) announced his plans to introduce legislation that will forever protect the rivers that hold some of our most sacred and informative stories as Montanans.

On Tuesday, October 27th, as I drove the long winding lane from Trout Chasers Lodge in Gallatin Gateway, down to the banks of the Gallatin River, I was overflowing with excitement and nervousness. As a steering committee member of the coalition Montanans for Healthy Rivers, I had been helping to plan a press event with Senator Jon Tester’s staff for weeks. This was a moment many of us had been waiting for the last several years or more: The Senator planned to announce he would be introducing the Montana Headwaters Legacy Act.

If you’ve read any of my past blogs or spend time in the river world, you are probably already very familiar with the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. As the highest form of protection a river can receive, Wild and Scenic designation forever maintains a river’s free flowing nature, clean water and “outstandingly remarkable values.”

Montana’s original Wild and Scenic Rivers – the North, Middle and South Forks of the Flathead River and the Upper Missouri River – were all designated in 1976. Montana did not have another Wild and Scenic designation until East Rosebud Creek gained protection in 2018, bringing the state’s total miles of federally designated Wild and Scenic Rivers to just shy of 400. This still amounts to less than ¼ of 1% of the state’s total river miles.

When the Montana Headwaters Legacy is passed, it will nearly double the number of river miles in Montana that are protected forever as clean and free-flowing.

After parking my vehicle and getting out to greet my colleagues, I took a few moments to absorb my surroundings. The excited chatter of reporters and supporters alike, the smell of a campfire burning to lend some warmth to attendees, and the sound of the Gallatin River in the background will forever cement that day in my memory. To say this is a milestone in the state’s conservation history is an understatement, let alone in my career as a conservation professional.

I have met Senator Jon Tester a few other times over the years, but this time was going to be different. On this occasion, I would be listening to him announce his plans to introduce legislation that my colleagues and I have spent the last nine years of our lives crafting and gathering support for. To be clear, this type of thing doesn’t happen too many times during a conservation-focused career. And legislation that leaves a long-lasting legacy like this one doesn’t happen too many times in a lifetime.

Like many important occasions of my life, the entire press event went by in a flash. I was so focused on capturing the event for social media, I couldn’t remember what anyone said until I watched it later on my phone at home. And now, almost two days later as I write this blog, am I only starting to put words to my emotions around what happened this week and the weight of its significance.

For those that grew up in the 90s and watched the sitcom “Family Matters,” you might recall the theme song and infamous line, “it’s a rare condition this day in age, to read any good news on the newspaper page.” I feel that’s especially true lately when the shock of each day’s headlines seems to top the previous day’s, and so on and so on. On the rare occasion that good news makes headlines or a reason for celebration presents itself, I find myself humming that tune.

Well friends, this was one of those occasions.

After the press event concluded, a few of my fellow coalition members and I bought a six-pack of beer and traveled down to a nearby river access site to toast the day’s event. At that moment and in the one which I’m writing, I can’t help but reflect on the feeling of immense gratitude.

I felt gratitude as I watched Senator Tester drive off towards home, after an extremely long travel day from Washington D.C., on top of several long days of hearings in the Senate. I feel gratitude for leaders like Senator Tester who make decisions with conviction and genuine care for their constituents and the generations of people they will never know. I feel gratitude for my colleagues in this movement, who work tirelessly for the causes they believe in and the people behind those causes.

It feels a bit like I’m giving an acceptance speech for some award I didn’t win, but during these challenging times we find ourselves in, sifting out the moments I feel thankful seems to be the only way I can make sense of the world and feel comfortable in it.

I hope you read this and feel some sense of comfort in knowing that during such challenging times there can still be reasons to celebrate and be thankful for what we still have to protect. I encourage you to send Senator Jon Tester a personal thanks for this monumental step he is taking to secure Montana’s conservation legacy so that you and I can continue to create the stories that have shaped us to this point. A minute of your time now has the potential to give hours of time to future generations on a river that will undoubtedly shape them.

If you’d like to watch the event yourself, check out the live video stream.

While the national election still hangs in the balance, we have great news for the Colorado River, and rivers on Colorado’s Front Range.

Across the western slope, more than 70% of voters easily passed Ballot Measure 7A, providing much needed funding for the Colorado River District. The ballot measure would raise property taxes across the River District and was approved in 14 of the 15 counties in the district’s region. American Rivers, and several diverse partners were strong advocates for the measure.

A second measure, also on the ballot as 7A, passed on the Front Range, in the St. Vrain – Left Hand District, which encompasses parts of Boulder, Larimer, and Weld Counties. While a smaller district, the success of the measure (similar in structure to the Colorado River District’s question) is no less important to water supply, water quality, and stream health in the area. The measure passed with 68% of the vote – a remarkable accomplishment in such a divided time.

Matt Rice, American Rivers Colorado Basin Director, said that the results prove that water, and protecting the Colorado River, is one issue where western slope voters are united.

“This is a big win for the Colorado River, the two River Districts, and the future of Colorado’s water supplies. The overwhelming support for these measures shows that Coloradans value healthy rivers for our environment, economy and our future. In a polarized election season, we proved that water, and rivers, connect us.”

In their implementation plans, the River Districts plan to use funds raised by the ballot measures to go towards funding water projects backed by local roundtables and communities in five categories, including healthy rivers, water quality and watershed health, productive agriculture, infrastructure improvements, and conservation and efficiencies.

It has never been more urgent to support funding for the Colorado River. 20 years of drought caused by climate change and increasing demand have diminished water supplies, put the health of rivers at risk and threaten the viability of agriculture. 65% of the flow in the entire Colorado River Basin originate in the Colorado River District’s jurisdiction.

The Colorado River, like all rivers, is critically important to communities on both the West Slope and the Front Range, and to the state of Colorado as a whole. The Colorado River drives a $3.8 billion dollar recreation economy, generates over 26,000 recreation related jobs, and irrigates thousands of acres of farmland.

This is a guest blog by David Stokes, Executive Director of Great Rivers Habitat Alliance.

The City of St. Charles, Missouri, sits between the Missouri and Mississippi rivers within the peninsular county of the same name. Like almost all cities and counties within major floodplains, St. Charles has experienced significant flooding events in recent years. Many of their flooding problems have been caused by irresponsible floodplain developments in neighboring cities and counties.

In early 2020, the City of St. Charles announced it was embarking on two new studies for major levee projects to “protect” parts of the city. The proposed Elm Point levee within the Mississippi River watershed is a typical “build it and they will come” floodplain development project intended to take undeveloped land out of the floodplain (as defined by FEMA) via a new 500-year levee to allow for major commercial development after the levee is built. These types of floodplain developments have been a common occurrence in the St. Louis-region, leading to increased flooding, environmental damage, abuse of tax subsidies, and further harms.

The other proposal, the Frenchtown levee alongside the Missouri River, is slightly more defensible. In this case, existing residents and businesses have seen increased flooding, and the city is trying to help address the situation. While a new, 500-year levee is not the proper answer (and will only make flooding worse for someone else nearby), the people of the Frenchtown neighborhood do deserve help.

Great Rivers Habitat Alliance became concerned as soon as we heard about these proposals. We raised our objections to community groups, local media, and to St. Charles city and county officials. Our objections focused on these projects being just the latest additions in the ongoing regional levee race that has resulted in water being higher and flooding being worse for all our communities. This levee race costs enormous amounts of money, harms the environment, damages vital habitat, and threatens public safety by creating larger and faster floods.

In July, we were informed by Mayor Dan Borgmeyer of St. Charles that the city was cancelling the Elm Point levee study. While they are continuing with the Frenchtown study, it was a great win for the environment that the Elm Point levee proposal has been cancelled. It was also a relatively fast win. For non-profits used to drawn out policy fights that can last for years (including one our organization had with the neighboring city of St. Peters, Missouri, from 2005 to 2011), convincing a local government to cancel a bad proposal this quickly is uncommon. How did it happen and what can we all take from it?

I think the most important lesson is the importance of routinely following the agendas of local governments in the regions your organization may cover. We learned about these two studies in their embryonic stages just after they had been proposed. Too often, activists hear about projects of all types well after the backers have performed much of the behind-the-scenes work, including consulting fees, preliminary engineering work, etc., that can cost significant money. Spending that money makes it more difficult for a government to just cancel a project. We learned about and began objecting to the Elm Point levee early on, making it easier for the city to listen to our arguments and end the project before expending taxpayer money.

Another lesson is the importance of building good relationships with local officials. In our meeting with city officials, local media, and other groups, we always kept our objections professional and never let it devolve into a personal dispute. Since the decision to end the project, I have given credit where it is due – and will continue to do so – by properly praising Mayor Borgmeyer and other city officials for this great decision. We want a good relationship with the Mayor so that we can be a part of the conservation and debate about the Frenchtown levee. The pressures from developers to pave over America’s floodplains never ends. All we can do as activists is be prepared to fight for our beliefs as effectively as we can.

David Stokes is a Saint Louis native and a graduate of Fairfield (Conn.) University. Stokes has been the executive director of Great Rivers Habitat Alliance (GRHA) since 2016. He focuses his efforts on preserving the Confluence floodplain of the Mississippi, Missouri, and Illinois rivers from harmful development. Prior to joining GRHA, he was an assistant to Saint Louis County Councilman Kurt Odenwald from 2001 through 2006. Stokes was a policy analyst at the Show-Me Institute from 2007 to 2016. He currently serves on the University City Commission for Access and Local Original Programming (CALOP) and is a past president of the University City Library Board. Stokes was the 2012 representative to the Electoral College from Missouri’s First Congressional District. He lives in University City, Missouri with his wife and their three children.

This blog was written by Jeff Odefey, American Rivers; Shanyn Viars, American Rivers; Janet Clements, Corona Environmental Consulting; Caroline Koch, WaterNow Alliance

American Rivers, Corona Environmental Consulting, and WaterNow Alliance are delighted to congratulate the first Green Infrastructure Funding Academy cohort on their completion of this in-depth funding and financing training series. Unbowed, and perhaps even further motivated, by this volatile period in utility management and in the face of uncertain local conditions, participants came together over the past six months to gain a deep understanding of stormwater credit trading and debt financing structures and opportunities. The cohort included representatives from Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District; Tuscon, Arizona; Greensboro, North Carolina; Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Cook County, Illinois; Eugene, Oregon; Atlanta Department of Watershed Management; Sheboygan, Wisconsin; San Mateo County, California; Metropolitan St. Louis Sewer District; and Green Bay, Wisconsin—cities and utilities across the country representing a diversity of stormwater challenges and perspectives.

In five workshops, the Academy curriculum covered a range of issues informed by the participants’ unique and common stormwater management and green infrastructure implementation challenges. Building from an initial convening to find common ground around key goals and expectations, we launched into a series of monthly web-based workshops that covered the fundamentals of stormwater credit trading and essential information related to using debt financing for green infrastructure projects. Through these sessions, staff from the partner organizations and outside experts led discussions into the feasibility of both approaches, and the detailed, often arcane essentials related to economic, legal and tax considerations. Finally, in October 2020, the Academy culminated in a two-day conference that allowed us to devote considerable time and attention adding detail to earlier topics and exploring other issues of concern. These longer sessions brought Academy participants together with industry leaders, academic experts and community advocates in a unique and rewarding opportunity for small group conversations.

While the cohort’s stormwater challenges ranged from flooding to combined sewer overflows to compliance with MS4 permits, a few common themes emerged over the course of the Academy. The group grappled with ongoing operation and maintenance concerns and heard about opportunities to support local workforce development as a possible solution. Participants shared their concerns about the cost of administering a stormwater credit trading program and learned of ways to streamline that process. The cohort reviewed the legal, accounting, and tax implications of using municipal bonds to finance green infrastructure investments on private property and gained insights into the types of projects that can be part of a stormwater system.

With the Green Infrastructure Funding Academy now at a close, we have four key takeaways. First, as the Academy organizers, we are not only grateful for our participants’ thorough engagement and interest in these issues but are also impressed by their eagerness to learn—from Academy presenters as well as each other—and consider new approaches to age old challenges. Second, alternative financing methods allow municipalities to fully capture the multiple benefits of green infrastructure including job growth through green/blue careers, increased walkability, reducing urban heat island, among many others. Third, collaboration between agencies, NGOs and community leaders is important to achieving stormwater goals and fostering climate resilient cities. Finally, scaling adoption of green infrastructure will not only take creative market-based approaches and capitalization of private property investments but also identifying stable operation and maintenance funding.

American Rivers, Corona Environmental Consulting, and WaterNow Alliance look forward to hosting future green infrastructure workshops and working with communities as they continue to build sustainable, resilient water management solutions. If you’re interested in participating in a future workshop or learning more about stormwater credit trading or debt-financing, please feel free to contact Jeff Odefey at jodefey@americanrivers.org for inquiries to American Rivers or Caroline Koch at cak@waternow.org for inquiries to WaterNow Alliance.

Saturday, October 24th is World Fish Migration Day, a one-day global celebration of migratory fish and open rivers. Every day is a good one to celebrate and advocate for connected rivers, and as spring runs of migratory fish are making their way up river it is a particularly good time.

Many species of fish migrate between freshwater and salt water as a key part of their life-cycle. Some fish, such as well-known species of salmon, spawn in freshwater and then migrate out to the ocean where they grow to be adults, returning to rivers to spawn. Still others do just the opposite, like the American eel, living their adult lives in freshwater and returning to the open ocean to spawn. Their paths are as diverse as the fish themselves. West coast Chinook salmon have been tagged traveling as much as 3,500 miles, while some east coast river herring are content to travel a few miles upstream to a freshwater pond for spawning.

The Mill River is diverted as a worker uses a saw to begin the removal of the West Britannia Dam in January 2018, the final of three removals in Taunton Massachusetts. | Amy Singler

It isn’t only the ocean-going fish that need to move. Fish that live the entirety of their lives in freshwater also move between different types of habitat throughout their lives, accessing tributaries, the floodplain, and the main channel. These fish are persistent in their efforts. Brook trout at one study site in western Massachusetts have been recorded repeatedly attempting a 2-foot leap into a metal culvert in order to access a small side tributary protected from larger fish in the main channel.

We don’t make it easy on the fish to get where they are going. On most rivers dams stand in their way, blocking access to upstream habitat and creating challenges navigating downstream. Levees separate channels from nursery floodplains. Roads-stream crossings disrupt habitat connectivity even at the small scale.

Without access to vital habitat, fish populations decline. We need to support efforts to reconnect and keep connected rivers through removing unnecessary dams, reconnecting floodplains, managing our water use, and managing hydropower for sustainable rivers. And that is what World Fish Migration Day is all about.

Celebrate connected and healthy rivers with us. Keep an eye on our social media. Find a World Fish Migration Day event close to join at http://www.worldfishmigrationday.com/.

This article first appeared in The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

For decades, the neighborhoods of Peoplestown and Summerhill have suffered from flooding and sewage overflows, exacerbated by the stormwater runoff from nearby highways and parking lots surrounding the former Olympic Stadium. When it rains, the stormwater rushed over the pavement, overwhelming aging water infrastructure and causing health risks and property damage. It’s the type of longstanding environmental injustice that communities of color face here in Atlanta and nationwide.

The area, the headwaters of Intrenchment Creek, is a tributary to Atlanta’s other river, the South River, and was once covered in trees and lush vegetation. The soil could naturally soak up rainwater, and the creek could shrink and expand with the seasons and storms. Fast forward to today: downtown’s high-rise buildings, the State Capitol, sprawling parking lots and highways dominate the headwaters. So when we — with our many local partners and community leaders —began to confront the challenge of modern-day flooding and sewage overflows, we looked to nature for lessons. To restore clean water and the healthy hydrological function of the watershed meant designing solutions including “bioretention” cells — or large rain gardens—to capture and infiltrate stormwater, as well as plantings to filter pollutants.

The project was completed in the spring and is the first of its kind in Georgia — the Georgia Department of Transportation’s first-ever green infrastructure retrofit. We’re thrilled with the result. The two bioretention cells east and west of the Capitol Avenue bridge will infiltrate 750,000 gallons of stormwater runoff from the highways annually. The landscaped rain gardens will provide ongoing beautification to the area and, if scaled, could go a long way toward enhancing this gateway to Atlanta. And to gauge the success of the project long-term, the University of Georgia is assessing the amount of runoff reduction and monitoring bacteria and nutrient levels in the stormwater discharge.

This project is part of a larger effort on the part of the Intrenchment Creek One Water Management Task Force, a partnership of local community leaders, environmental justice advocates at Atlanta-based ECO-Action, government agencies, businesses, and the City of Atlanta Department of Watershed Management. The aim? To address flooding and sewer overflows and secure community benefits. The project was made possible with $400,000 of GDOT funding, a $197,745 grant from the Georgia Environmental Protection Division and support from Central Atlanta Progress and the Turner and Kresge Foundations. And the project will continue to thrive with ongoing maintenance provided by Central Atlanta Progress.

This investment will pay dividends for years to come. A new report by American Rivers, “Rivers as Economic Engines: Investing in Clean Water, Communities and our Future”, details the jobs and economic benefits of investing in this kind of water infrastructure and river restoration. It also makes the case for a federal investment of $500 billion over the next 10 years to benefit clean water and healthy rivers. That kind of investment would benefit Georgia and communities nationwide. Such an investment could mean more successful efforts like those in the Intrenchment Creek headwaters.

Here in the heart of the city, we’re showing how the issues of clean water and community strength are interconnected, and how the only way forward is by working to address these issues together.

Today, the Trump Administration officially put forward a proposal to build the Yazoo Pumps – a shockingly irresponsible project that will put tens of thousands of people at risk, threaten the integrity of the Clean Water Act, and degrade hundreds of thousands of acres of globally significant natural resources.

The Yazoo Pumps was vetoed under President George W. Bush in 2008 because it would drain or damage globally significant wetlands in the Mississippi-Yazoo Delta, the historic Mississippi River floodplain north of Vicksburg, MS. Despite the veto, the Trump Administration is proposing the move forward with constructing the Yazoo Pumps under the auspices of “flood control.” However, the project will actually increase flood risk for most people living and working in the area.

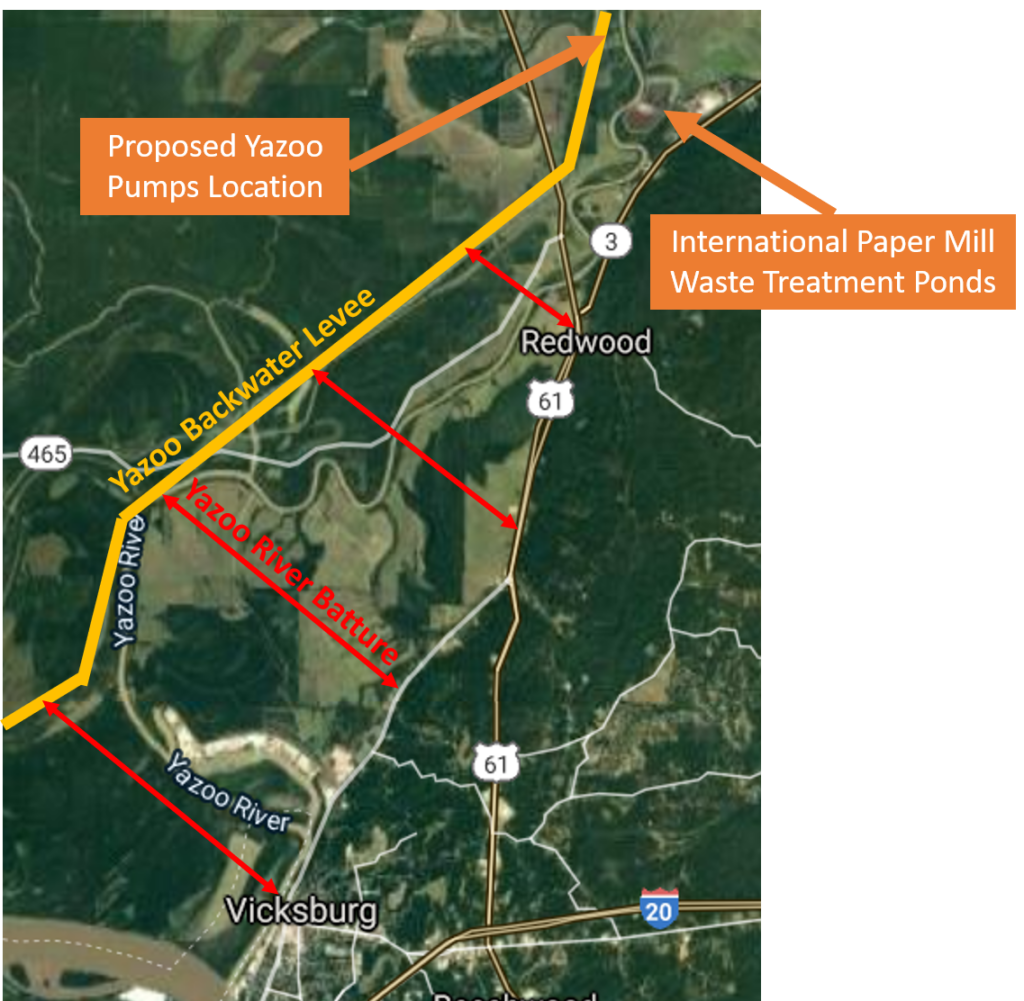

Communities in the Yazoo River batture land north Vicksburg, MS will see a lot more water as much as 9 billion gallons of water will be pumped into the Yazoo River every day during flood events. Just downstream of the pump’s proposed location, the International Paper Mill has two wastewater treatment ponds in the Yazoo River floodplain that are protected by low berms. Should those berms give way, the residents in downstream Vicksburg, MS could be flooded with toxic water from the paper mill’s treatment ponds.

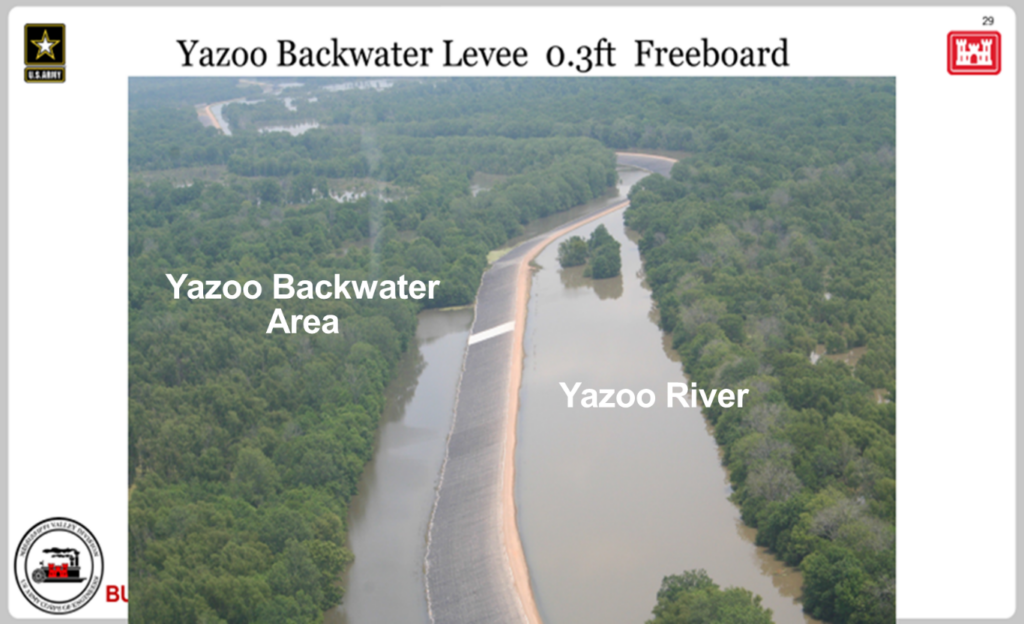

And, horrifyingly, the Yazoo Pumps would actually threaten to flood the very people it is falsely touted to protect. By pumping an additional 9 billion gallons of water per day into the Yazoo River during flood events the project would actually threaten the integrity of the Yazoo Backwater Levee. This levee was within inches of overtopping during the 2019 Flood. If the Yazoo Backwater Levee fails, the entire Mississippi-Yazoo Delta would flood, threatening more than 41,000 people and almost 19,000 structures.

The decision by the George W. Bush Administration to veto the Yazoo Pumps safeguards vital wetlands in the Delta National Forest, Panther Swamp National Wildlife Refuge and countless other conservation areas in the Mississippi-Yazoo Delta. These wetlands represent some of the last remaining bottomland habitat that is still partially connected to the Lower Mississippi River and provide critical habitat to hundreds of fish and wildlife species. The Mississippi-Yazoo Delta is in the heart of the Mississippi River flyway – a migration corridor that conveys a vast array of migrating species traveling the globe.

- Millions of birds use the area during their fall and spring migrations. This includes 20 percent of the nation’s duck population!

- American eels migrate from their breeding grounds in the mid-Atlantic Sargasso Sea to North American rivers, using floodplain wetlands, like those in the Mississippi-Yazoo Delta, to grow and mature on a rich diet of frogs and insects.

- Even tiny ruby-throated hummingbirds and monarch butterflies can be spotted loading up on nectar-rich flowers before flying across the Gulf of Mexico to their over-wintering grounds in South and Central America.

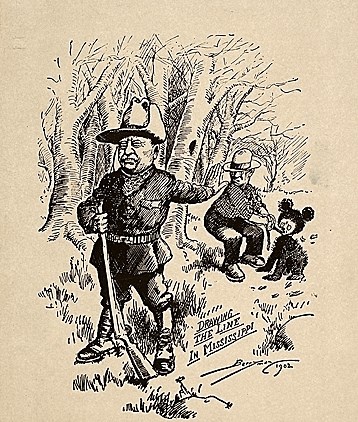

In addition to migrating species, this area is important to several at-risk species, including the federally-threatened wood stork, the federally-endangered pallid sturgeon, the federally-threatened American alligator, and the state-endangered Louisiana black bear. The Louisiana black bear is the species renown for inspiring the Teddy Bear. President Theodore Roosevelt refused to shoot one that had been tied to a tree on the banks of the Big Sunflower River in the Mississippi-Yazoo Delta – the very same area at risk today! The bear was recently removed from the federal threatened and endangered species list thanks, in part, to reintroduction efforts in the Mississippi-Yazoo Delta.

While President George W. Bush’s administration vetoed the project because of the catastrophic environmental impacts, it’s not just fish and wildlife who need these wetlands. The Mississippi-Yazoo Delta is also a critically important aquifer recharge zone for the Mississippi River Valley Alluvial Aquifer, part of the Mississippi Embayment, which provides drinking water for 8 million people in Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas, Missouri, Mississippi, Alabama, Tennessee, and Kentucky. Irrigation withdraws from this aquifer system to support cotton production in the southern states has already caused some of the most severe groundwater declines in the U.S. The Yazoo Pumps would siphon off water from wetlands that are critically important for the aquifer’s recharge, potentially exacerbating the region’s already significant groundwater depletion.

The Clean Water Act veto authority has only been used 13 times since the Act was authorized in 1972 to protect and restore the nation’s water resources. This decision to build the Yazoo Pumps, if allowed to proceed, would neuter the Clean Water Act veto authority and raises the specter of the 12 other projects that have been vetoed. This includes projects like Spruce No. 1 Surface Mine – one of the largest mountain top removal project ever conceived – and the Two Forks Dam – one of the largest water storage projects ever proposed in the West.

The Yazoo Pumps is a shockingly irresponsible project. Instead of building the Yazoo Pumps, investment is needed in projects and programs that will protect people from flood losses. These alternatives include buying out homes, elevating or flood-proofing infrastructure, and purchasing wetland easements from farmers. Local leaders need to work with state and federal agencies to find long-term affordable housing for poor residents who may be displaced to avoid climate change fueled flooding. Investing in these economic and sustainable options would provide financial security for residents while protecting and enhancing the valuable natural resources of the Mississippi-Yazoo Delta.

Take action today and tell the Trump Administration not to build the Yazoo Pumps!