Klamath River

Klamath River Named as 2024 River of the Year

American Rivers announced that Oregon and California’s Klamath River is the 2024 River of the Year, celebrating the biggest dam removal and river restoration in history. The River of the Year honor recognizes significant progress and achievement in improving a river’s health.

“On the Klamath, the dams are falling, the water is flowing, and the river is healing,” said Tom Kiernan, President and CEO of American Rivers. “The Klamath is proof that at a time when our politics are polarized and the reality of climate change is daunting, we can overcome seemingly insurmountable challenges and make incredible progress by working together. This is why American Rivers is naming the Klamath the River of the Year for 2024.”

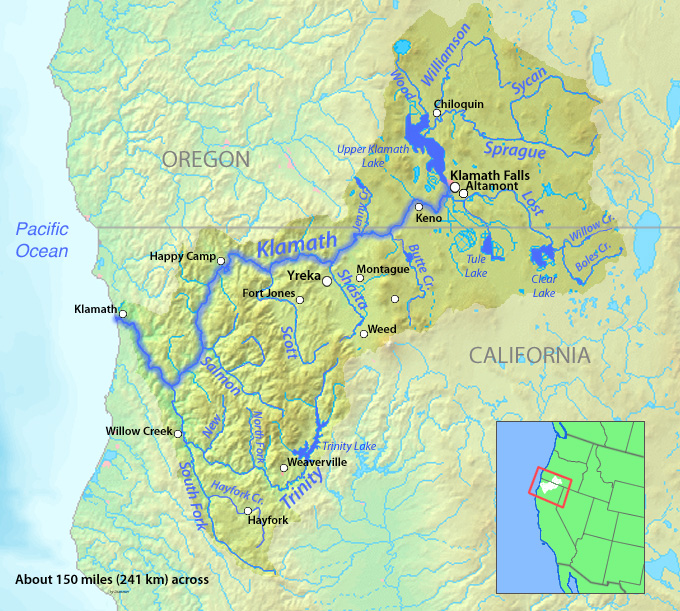

The Klamath River flows from a broad patchwork of lakes and marshes at the foot of the Cascade Mountains on the California-Oregon border and winds southwest into California. After passing through five hydropower dams, the river reaches the Pacific Ocean south of the fishing community of Crescent City.

The river has been home to indigenous people for thousands of years and tribes including the Yurok, Karuk, Hoopa, Shasta, and Klamath rely on, and care for, the river today.

Klamath River salmon runs were once the third-largest in the nation, but have fallen to just eight percent of their historic numbers. Chinook and coho salmon, steelhead and coastal cutthroat trout, green and white sturgeon, and Pacific lamprey all rely on the Klamath.

More than 75 percent of birds migrating on the Pacific Flyway feed or rest in the upper basin and the largest population of bald eagles in the lower 48 states winters in several national wildlife refuges there.

The Upper Basin

The upper Klamath basin has been called the “Everglades of the West.” However, almost 80 percent of the upper basin’s wetlands have been converted to grow thirsty crops such as potatoes, alfalfa, and hay, including nearly 23,000 acres on the Tule Lake and Lower Klamath National Wildlife Refuges. Irrigation withdrawals and polluted farm runoff have harmed the river and its fisheries.

Thanks to the efforts of our partners, MANY PROJECTS have been completed or are currently underway that are designed to improve water quality and fish habitat while making it easier for landowners to meet water quality goals that both satisfy regulators and ensure healthy water supplies for people and wildlife.

Did You know?

The Southern Oregon/Northern California Coast coho is federally listed as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act.

Low water flows in September 2002, led to the death of an estimated 34,000-70,000 chinook, coho, and steelhead on the Klamath, making it the largest salmon kill in the history of the American West.

With 286 miles classified as wild, scenic, or recreational, the Klamath is the longest Wild and Scenic River in California. Another 11 miles of the upper Klamath are designated in Oregon.

The Klamath River watershed is as big as Massachusetts and Connecticut combined.

What states does the river cross?

California, Oregon

Let's stay in touch!

We’re hard at work in the California for rivers and clean water. Sign up to get the most important news affecting your water and rivers delivered right to your inbox.

Guardians of the River

In this film by American Rivers and Swiftwater Films, Indigenous leaders share why removing four dams to restore a healthy Klamath River is critical for clean water, food sovereignty, and justice.

Watch: ‘Voices of the Klamath’ shorts

Klamath River Dams

Dam Removal on the Klamath River

For nearly 100 years, dams on the Klamath River have blocked salmon and steelhead trout from reaching more than 400 miles of habitat, encroached on Indigenous culture, and harmed water quality for people and wildlife. But now, four dams – J.C. Boyle, Copco No. 1, Copco No. 2, and Iron Gate – built between 1908 and 1962, are coming down. This river restoration project will have lasting benefits for the river, salmon, and communities throughout the Klamath Basin.

The original Klamath River agreements were crafted through the leadership of Tribes in the basin who came together with American Rivers and other conservation organizations, PacifiCorp, state and federal agencies, commercial fishing representatives, and members of the agricultural community to remove the dams, restore habitat and resolve decades-long water management disputes.

Dam removal will restore access to more than 300 miles of habitat for salmon. It will also improve water quality – currently, toxic algae in the reservoirs behind the dams threaten the health of people as well as fish.

Why is removing a dam important for a river’s healing? Dr. Ann Willis, California Regional Director at American Rivers, answers this question in front of one of 4 dams that will be removed as part of the largest dam removal project in history underway now on the Klamath River.

How does dam removal support communities? Dr. Ann Willis joins us from Iron Gate Dam on the Klamath River to reflect on the benefits of dam removal for salmon, clean water, Tribal Nations, and climate resilience.

But perhaps more important than the size of the dams is the amount of collaboration and the decades of hard work that have made this project possible. American Rivers has been fighting to remove the dams since 2000. Thanks to the combined efforts of the Karuk and Yurok tribes, irrigators, commercial fishing interests, conservationists, and many others, our goal of a healthy, free-flowing river is now within reach.

The Klamath River Renewal Corporation is managing the dam removal project.