White Salmon River

Wild Fish and Scenic Whitewater

Few things in life can top the intoxicating thrill of riding a whitewater raft or kayak down glacial runoff pouring from the flanks of a 12,000-foot volcano. Yet, in 2011, the White Salmon River found a way.

That was the year demolitions experts blew a gaping hole in the base of the 125-foot tall Condit Dam and reconnected the entirety of the White Salmon to the Columbia River, allowing the return of the once-abundant runs of wild salmon and steelhead that had provided physical, spiritual, and cultural nourishment to local Native American tribes. As an added bonus, the dramatic dam removal extended the whitewater thrill ride another five miles downstream, carrying paddlers all the way to the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area.

Not that the White Salmon is lacking for scenery in its own right. This iconic southwest Washington river flows from the snowy slopes of Mount Adams for 45 miles, more than 25 of which are federally designated as Wild and Scenic. The steep, breathtaking canyons and crystal clear water help drive a robust tourism and recreation industry around the river nationally recognized as a premier whitewater destination.

Ten outfitters run commercial trips on the river, and at least 25,000 boaters use the White Salmon each year, bringing an important economic influx to the local community. Paddlers now floating past the former dam site struggle to recognize the plug was ever there.

Did You know?

In addition to salmon and steelhead runs, the White Salmon is among the top three resident rainbow trout fisheries in the region.

The White Salmon offers Class III-IV whitewater in a natural setting that remains runnable virtually year-round.

At 12,307 feet, Mt. Adams (headwaters of the White Salmon) is the second highest peak in the Pacific Northwest after Mt. Rainier.

Condit Dam was the largest dam ever removed in the United States until the Elwha Ecosystem Restoration Project on the Olympic Peninsula removed the larger Elwha Dam and Glines Canyon Dams.

WHAT STATES DOES THE RIVER CROSS?

Washington

The Backstory

Built in 1913 to generate hydropower, Condit Dam was an important part of the history and development of the area. But the benefits came at a high cost. The towering dam disrupted natural river flows and was built with no fish passage, limiting salmon and steelhead to the lower three miles of river.

Condit ultimately created more ecological problems than it did electricity (an average of just 10 megawatts) and soon outlived its usefulness. Faced with the mounting costs of operating the aging dam, owner PacifiCorp signed an agreement in 1999 with diverse interests including American Rivers, the Yakama Indian Nation, government agencies, and other partners to remove it.

Let's stay in touch!

We’re hard at work in the Pacific Northwest for rivers and clean water. Sign up to get the most important news affecting your water and rivers delivered right to your inbox.

When the hole was blasted in Condit’s base in October 2011, the reservoir behind it drained in a matter of hours. Today, salmon have returned to historic upstream spawning grounds on the free-flowing river and the number of whitewater paddlers visiting the White Salmon continues to grow.

The Future

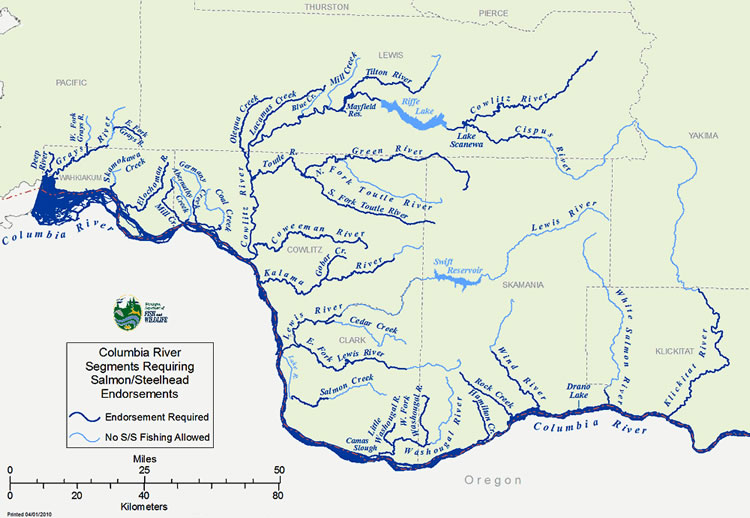

With the White Salmon once again flowing freely into the Columbia River, migrating salmon and steelhead have only the Bonneville Dam just downstream from the confluence to overcome. Bonneville does include fish ladders, although the large concentration of salmon awaiting their opportunity to swim upstream now attracts several California sea lions who prey on the fish. The dam has also blocked the upstream spawning migration of white sturgeon, although they still spawn in the Columbia River below Bonneville.

In 1986, the lower White Salmon between Gilmer Creek and Buck Creek earned Wild and Scenic designation, followed by a longer segment of the upper river between the headwaters and the boundary of the Gifford Pinchot National Forest in 2005. Further support for the Wild and Scenic campaign will help keep development threats in check and ensure the river will remain in its relatively pristine state for generations to come.