Upper Basin of the Colorado River

The Colorado River provides water to nearly 40 million people, flows through 9 National Parks, and drives a $1.4 trillion economy. If the Colorado River basin were a country, it would be the world’s 7th largest by economic output. But the river is stretched to its limit. Climate change and increasing water demand due to an expanding population is and will continue present significant challenges that if left unaddressed, will impact our regional and national economies, degrade the environment, challenge our agricultural heritage and food production, and limit recreational opportunities from fishing and boating to skiing.

The Upper Colorado River Basin, defined by the river network above Lee’s Ferry in northern Arizona, is comprised of 4 states – Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming. Collectively, the Upper Basin States contribute the vast majority of the water coming in to the Colorado River Basin, primarily through winter snowpack, but with the impacts of climate change altering the amount of snowpack and timing of spring runoff, water supply in the Colorado River is increasingly strained.

Colorado

Colorado, known has the Headwaters State, is home to the headwaters of 4 major river basins; the Platte (northern Front Range), the Arkansas (southern Front Range), the Rio Grande (southern Colorado), and the Colorado (Western Colorado), and collectively supplies water to 17 western states. The main-stem Colorado River flows west from Poudre Pass on the west slope of Rocky Mountain National Park, and connects to world renowned tributary rivers for fishing, whitewater, and agriculture such as the Animas (via the San Juan), Eagle, Dolores, Gunnison, Yampa, Blue, and Roaring Fork Rivers. By volume, the Colorado River Basin is the largest in Colorado.

Wyoming

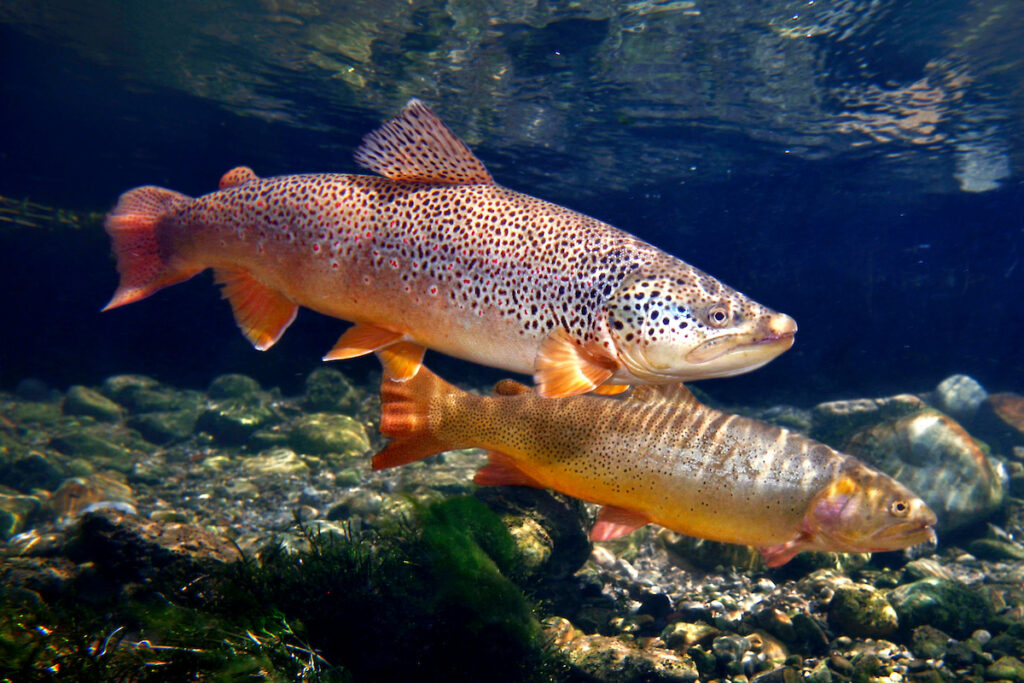

The Green River, the largest tributary to the Colorado, flows out of the Wind River Range, south of Jackson Hole. The Green provides water for thousands of acres of irrigated ranch land, offers excellent trout fishing opportunities in the upper reaches, and flows through some of the nation’s most striking canyons including Flaming Gorge and Gates of Ladore. The Green’s flow nearly doubles when it joins the Yampa in Dinosaur National Monument in northwestern Colorado.

New Mexico

New Mexico is home to the longest undammed tributary in the Colorado River Basin, the Gila River. While New Mexico is an Upper Basin State, the Gila River flows southwest into the Lower Basin state of Arizona, providing water to farmers, cities, and Native American Tribes, as well as supporting endangered birds and fish, like the Southwestern Willow Flycatcher and Gila Trout. Like Denver and other Front Range cities, Santa Fe and Albuquerque also depend in part on the Colorado River even though they are located in the Rio Grande Basin. The San Juan Chama project diverts water out the San Juan river in Colorado to the Rio Grande to support agriculture and municipal water supply.

Utah

Below Flaming Gorge Dam, the Green River flows several hundred miles through Utah (and 26 miles through Dinosaur National Monument in Colorado). Multiple tributaries including the Yampa, White, Duchesne, and the San Rafael rivers join the Green River on its way to Lake Powell. After leaving Wyoming (and Colorado), the Green flows through a spectacular red-rock landscape, including Desolation-Gray and Labyrinth Canyons before it meets the main-stem Colorado River in Canyonlands National Park. It then continues south through Cataract Canyon before flowing into Lake Powell. Once through Lake Powell, the river continues on through Glen Canyon Dam and shortly thereafter, through Lee’s Ferry (the delineation between the Upper Basin and Lower Basin) and into the Grand Canyon, 277 miles through one of our nation’s most iconic National Parks.

The Threats

The Upper Basin faces many of the same challenges as the Lower Basin – persistent drought, climate change, population growth. While water availability in the Upper Basin is more dependent on seasonal precipitation, it has been trending downward since 2000. Recognizing that diminishing river flows are creating risk for rivers, clean, safe, reliable drinking water supply for cities, and agricultural productivity, water managers, farmers, and conservation organizations are working together to develop an Upper Basin Drought Contingency Plan (DCP) which will identify and implement solutions allowing everybody who depends on the Colorado River to do more with less, share water more efficiently, and keep more water in the rivers for fish, wildlife, and recreation. Core to this vision is a developing program called Demand Management.

Demand management is a program that compensates farmers, cities and other water users on a voluntary basis to reduce water use without losing their legally allocated water rights. This saved water would then be left in the river to flow downstream to Lake Powell where it is “banked” to reduce water supply risk to the basin if drought persists. On its journey down to Lake Powell, the saved water would provide substantial environmental and recreational benefits for the river and could be timed in ways to benefit endangered fish, restore riverside habitat, and enhance recreational opportunities to support local economies. While there are a number of challenges in realizing a permanent Demand Management program in the Upper Colorado River Basin including ensuring that the conserved flows remain in the river, establishing a funding source to compensate water users, and providing certainty to water users that their right to water is protected. Conservation organizations like American Rivers, agricultural producers, and cities are increasingly working together to ensure Demand Management is part of the solution for how we manage our critical water supplies in the face of climate change and increasing demand.

Let's stay in touch!

We’re hard at work in the Southwest for rivers and clean water. Sign up to get the most important news affecting your water and rivers delivered right to your inbox.

Working together on solutions that provide benefits for rivers, agriculture, and people is key to American Rivers’ approach. We realize that if we are going to achieve lasting success in the Colorado River Basin, we must identify shared values and work with agriculture, cities, and other water users, and always with the overall health of our rivers in mind. In the Headwaters of the Colorado River, American Rivers is working with a coalition of ranchers, Trout Unlimited, and Front Range Water providers to restore over 30 miles of the Colorado River that has been severely dewatered due to water diversions that deliver water from the Colorado River to the Front Range. This project, known has the Colorado Rivers Headwaters Project, will benefit river habitat, water quantity and quality, and agricultural operations. When completed, The Headwaters Project will represent one of the largest river restoration projects in the Upper Colorado River Basin and provide a replicable model for how we restore rivers in the 21st century.

Our commitment to working alongside different water users has created opportunities to pursue innovative approaches to permanently protect rivers through new Wild and Scenic Designations and instream flow water rights – finding legal and practical ways to protect our rivers. Stabilizing the Colorado River Basin to ensure a positive future for nearly 40 million people is critically important for economies, and people, but so is the permanent protection of the basin’s last wild rivers. American Rivers is working to protect Colorado River tributaries like the Yampa River, the Crystal River, Upper Green River, and Deep Creek by pioneering approaches to river protection that works for all who rely on these amazing elements of our natural environment.