Escalante River

The Escalante River rivals the Paria for the steep and varnished canyon it winds its way through. Cottonwoods and hanging vines wedge themselves against canyon walls. The Escalante River is remote and rugged, its flows perennial and vital in an arid landscape.

When the first Anglos, members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, entered the valley, they were struck by the bounty of wild potatoes growing there, and deemed it “potato valley”. It was more romantically named during Powell’s 1872 survey expedition in honor of Silvestre Vélez de Escalante—who led the 1776 Dominquez-Escalante Expedition.

Upper Valley and Birch Creeks collide to form the Escalante, near its namesake town in south-central Utah. Atop the Aquarius Plateau, the headwaters cut through high alpine spruce forests before descending into old-growth ponderosa, pine, and aspen. At this high end of its reach, the Escalante provides critical habitat for mule deer, upon which the resident bear and mountain lion populations rely. The river carves its way off the plateau through a canyon with walls that reach nearly 1,100 feet in places.

The ephemerality of paddleable flows demands the same of those desiring to float it. Harry Aleson and Georgie Clark were the first, on record, to manage a trying float through the river’s canyon, timing their epic journey with the unpredictable spring and summer flows fed by early season runoff and monsoons.

Rated Class II overall, the Escalante can be deceiving. Aside from the fact that it’s nowhere near any beaten bath, there are a lot of variables: debris carried on flood waters can create strainers that require portages, floods themselves are a major risk, and there are few exits. For both the Escalante and the Paria, and as is the nature of so many desert rivers, the window to run is short, unpredictable, and unparalleled in humbling and spectacular scenery, and true adventure. During low flows, the canyon-carved river and its critical tributaries offer unmatched hiking and backpacking.

Did You know?

The Escalante River was one of the last sizable rivers to be discovered in the contiguous US.

During peak runoff, the Escalante can be as much as 100 bigger than the flows it maintains the rest of the year.

The Escalante River basin provides critical habitat and resources for nearly 300 species of birds, fish, mammals, reptiles, and amphibians.

What states does the river cross?

Utah

how can I help?

Stay informed with what is going on with rivers across the Southwest by following our Southwest River Protection Program.

Tell the Trump Administration to retain and support the Waters of the United States rule under the Clean Water Act. Take action here.

It is this—the river’s spectacular beauty, the habitat it provides, the adventure it inspires—that make the Escalante so vital to the Southwest. Though the Escalante River has been identified for Wild & Scenic protections by the National Park Service and various non-profits, this rare river is threatened by mining claims, impacts of climate change, and development. Constant threats including reductions to the size of Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument further imperil the rare intactness of this fragile desert ecosystem. For decades, volunteers have spent millions of dollars and countless hours to remove nonnative species and improve the river’s habitat and condition, but proposed management changes invite devastating impacts from increased grazing, mining, and oil and gas drilling, and erosion from OHV use that would directly impact water resources.

Elwha River

(Re)Born to be wild

Flowing from the heart of Washington’s Olympic National Park, the Elwha River is a sacred site. The creation story of the Lower Elwha Klallam people originates in the river’s fertile valley just east of Mt. Olympus, despite attempts to drown the Elwha behind a pair of towering dams a century ago. But the river once best known for its dams now serves as the home of America’s greatest re-creation story.

“The Elwha provides the most high-profile proof that dam removal works,” says Bob Irvin, president of conservation organization American Rivers. “On the Elwha, we are witnessing on a grand scale that rivers can come back to life if we just give them a chance.”

Claiming title to the largest dam removal project in history, the Elwha has once again run wild since August 26, 2014. The results have been astounding. Salmon runs at one time estimated at 400,000 fish annually are on track to surpass that number within the next 30 years. Bears, cougars, bobcats, mink, otter, and other wildlife sustained by the renewed food source have increased in abundance. Native plants are reclaiming riverbanks and silt and sand are moving downstream to rebuild the beach at the river’s mouth. It’s a living case study in the recovery and restoration of a wild river.

Did You know?

Elwha is a Native American word meaning “elk,” which winter in the valley.

The 210-foot Glines Canyon Dam is the tallest dam ever removed in the world.

The Olympic Peninsula, just west of Seattle, is the wettest place in the continental US, creating a dense concentration of rivers.

What states does the river cross?

Washington

other resources

Check out these other resources to learn more about the river:

The Backstory

The Elwha Dam stood 108 feet tall when it was built in 1913 just five miles from the river’s mouth in Puget Sound. It completely blocked robust runs of five different species of Pacific salmon from their native spawning habitat, stressing the ecosystem and obliterating tribal sustenance fishing. The 210-foot Glines Canyon Dam, built 14 years later, further obstructed the river and fish passage in what is now Olympic National Park.

After decades of work, sparked by a challenge to the relicensing of a hydropower dam within a national park, a coalition including the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, American Rivers, and other partners finally succeeded in authorizing dam removal and securing federal funding for the Elwha River restoration project in 1992. Elwha Dam removal began in September 2011, and the river was fully reconnected with the final blast to the Glines Canyon Dam in August 2014.

The Future

The Elwha is a story of a river returning to life. From its 6,000-foot headwaters in Olympic National Park to its mouth at the Strait of Juan de Fuca, the river once again flows freely from source to sea, with the rare benefit of being almost completely protected by park boundaries. Revegetation efforts throughout the formerly flooded valleys are ongoing, with park botanists and volunteers planting more than 400,000 native plants in the newly exposed sediment. What happens next, however, is up to Mother Nature.

But the immediate ecological and cultural benefits are undeniable. Local tribes and visiting anglers alike may once again thrive on the natural bounty of migrating fish. Now reconnected, the ecosystem is repairing itself, from the riparian old-growth forests reaping nutritional benefits from decomposing fish right down to orca whales thriving off a regenerating food source. With reestablished river flows, boaters, hikers, and other visitors are rediscovering the lush forests, deep valleys, and mountain views surrounding the Elwha River.

More than 100 years of dams does, however, take a toll on a river. Scientists say it could take a generation or more for the Elwha to fully heal. But it makes for compelling theater as the world watches a rare river rebirth. If there’s a better comeback story in American river restoration, we’re still waiting to hear it.

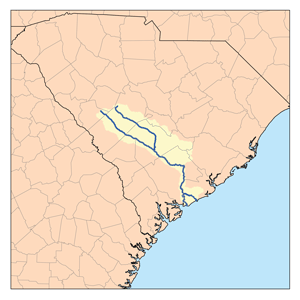

Edisto River

south carolina’s black beauty

As the longest free-flowing blackwater river in the nation, the tea-stained Edisto River is an intimate attraction that may serve as the single most inviting canoe run in South Carolina. No dams or rapids are found anywhere on the Edisto, just the lazy, lolling current and relaxing ambience one might expect from such a picturesque Southern sanctuary.

The river ranks among the prettiest in the East, framed by massive oaks draped in Spanish moss and the largest old-growth stands of tupelo-cypress in America, as it ambles from spring-fed headwaters in the central Sandhills, through the heart of floodplain forests to the rich estuary of the Ashepoo/Combahee/Edisto (ACE) Basin. It’s a paddler’s paradise of some 250 miles, punctuated by the 56-mile Edisto River Canoe and Kayak Trail passing through both Colleton and Givhan’s Ferry state parks, both offering camping and picnicking sites.

Francis Beidler Forest is a 15,000-acre National Audubon Society Sanctuary that’s an internationally renowned destination for spotting dozens of bird species, mammals, reptiles, amphibians, and several rare plants. The Edisto passes through the sanctuary where it meets the braided bottomlands of Four Holes Swamp. Stay on the lookout for redbreast sunfish and other fauna, including wild turkey, beaver, kingfisher, great blue heron, and egrets along the way.

THE BACKSTORY

Following the South Fork of the Edisto’s appearance in the 2014 America’s Most Endangered Rivers® report, the main stem landed on the list proper in 2015. It is the state’s most heavily used river for irrigation, and excessive water withdrawals continue to be a major threat to the Edisto, along with other rivers across the state.

While South Carolina has made great strides in reducing industrial and municipal impacts on river health and clean water through permits required during droughts and low flow periods on area rivers, the state needs to meet 21st-century needs for all water users and not just select groups. As it stands today, water policy still allows some water users to withdraw as much as one third of the river during low flow periods, enough water to supply a medium-sized city.

Did You know?

The Edisto is the longest free-flowing blackwater river in America.

It’s the only major river system in South Carolina completely contained in the state.

Both the endangered short-nosed sturgeon and Atlantic sturgeon, which can reach lengths of more than 10 feet, are known to spawn in the fresh water of the Edisto River.

What states does the river cross?

South Carolina

Such dramatically reduced flows have far-reaching consequences, including allowing salt water to encroach higher upstream, potentially killing trees and displacing wildlife that depends on fresh water. Fish habitat suffers, recreational opportunities are threatened and downstream users are increasingly uncertain of their fate.

The Future

American Rivers continues working to provide sustainable water supplies for all, while supporting river health and recreation on the Edisto.

More than 130,000 acres of land have been protected through public/private partnerships in the heart of the ACE Basin, qualifying it as one of the most acclaimed freshwater natural areas found on the East Coast. Undammed and largely undeveloped, the Edisto serves as one of the premier examples of a southern blackwater river from source to sea. It deserves to remain such.

East Rosebud Creek

OFF THE BEATEN PATH

If you truly want to discover the natural wonder and beauty of Montana and the Beartooth Mountains, take “The Beaten Path.” It’s a 25-mile backcountry hiking classic traversing over-the-top alpine scenery between dramatic canyon walls interlaced with waterfalls and more than a dozen sapphire lakes brimming with wild trout. At the heart of it all is East Rosebud Creek.

Did You know?

Montana currently has four Wild and Scenic Rivers – a 150-mile reach of the Upper Missouri and the North Fork, South Fork, and Middle Fork of the Flathead River.

All four of Montana’s Wild and Scenic Rivers were designated in 1976.

Along with the Stillwater Trail, East Rosebud Trail (“The Beaten Path”) is one of two trans-Beartooth Mountain routes.

What states does the river cross?

Montana

The path’s formal name is East Rosebud Trail. Originating near Red Lodge, the hike’s fame stems largely from the East Rosebud Valley, cut from the creek’s cascading waterfalls as it tumbles from the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness near Granite Peak (Montana’s highest at 12,807 feet). Just before it leaves the mountains, East Rosebud Creek flows through East Rosebud Lake before spilling into a glacially carved valley and then joining the Stillwater River, a tributary of the Yellowstone.

Both East Rosebud Creek and Lake have long been popular areas for trout fishing, whitewater paddling, hiking, and mountaineering. A cluster of cabins lines the north side of the lake, forming a quaint alpine village. Moose browse the willows while raptors soar overhead.

Because of its outstanding scenery, recreation, and geology, the U.S. Forest Service has declared 13 miles of East Rosebud Creek above the lake and 7 miles below it eligible for designation under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, our nation’s most powerful river protection tool. One look at the stunning beauty of East Rosebud Creek should convince even the fiercest skeptic that it is deserving of Wild and Scenic designation.

The Backstory

East Rosebud’s widely-popular Wild and Scenic campaign originated in 2009, when Bozeman-based Hydrodynamics Inc. applied for a permit to build a hydropower project on East Rosebud Creek. The project would have been located on public land within the Wild and Scenic–eligible reach just below East Rosebud Lake, and would have entailed building a 100-foot wide diversion dam, a 2-mile long penstock, substation, powerhouse, and transmission lines.

American Rivers and several of its conservation partners filed formal objections to the project and launched an aggressive media campaign that eventually pressured the hydropower company to abandon it in 2013. Although the dam is no longer an immediate threat, the proposal was the second of its kind since the year 2000, suggesting the need for constant vigilance.

The Future

In August 2018 President Trump signed the East Rosebud Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, which permanently protects 20 miles of the creek from all new dams, diversions and other threats and established Montana’s first new Wild and Scenic River since 1976 and the state’s fifth overall.

Dolores River

After nearly 20 years of collaborative work, Colorado Senator Michael Bennet introduced the Dolores River National Conservation Area and Special Management Area Act in July 2022. Colorado Senator John Hickenlooper co-sponsored the bill, and Colorado Congresswoman Lauren Boebert introduced companion legislation in the House, emphasizing the bipartisan nature of this proposal. The Act was introduced at the behest of Dolores, Montezuma, and San Miguel counties, as well as the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, agricultural producers, fish and wildlife managers, and conservation and recreation organizations.

The resulting legislation is bi-partisan and consensus-based, establishing a new National Conservation Area and Special Management Area that will protect wildlife, cultural and historical resources, and existing uses of the land while enhancing local economies well into the future.

What states does the river cross?

Colorado, Utah

WHAT CAN YOU DO?

Please join us in thanking Senator Bennet for introducing the Dolores River National Conservation Area bill!

Stay informed with what is going on with rivers across the Southwest by following our Southwest River Protection Program.

ABOUT THE DOLORES RIVER

The River of Our Lady of Sorrows, the Dolores River, was named “El Rio de Nuestra Senora de Dolores” when a Spanish trader encountered the river in 1765. But in many ways, the only sorrowful thing about the Dolores River is that like so many rivers in the West, it is, perhaps, too well loved, resulting in chronically low flows. Recently introduced National Conservation Area legislation has brought the Dolores River back into the spotlight.

Humans have lived in the region the Dolores flows through for more than 10,000 years, and the archeology in some of the steep, sandstone canyons is unmatched. Now, humans treasure this high-desert river for its sacred value, the crops and cattle it waters, the habitat it sustains for plants and wildlife, the amazing experience of boating it, and the clean water it provides for drinking, among other things.

With headwaters at 14,000 feet and a nearly 230-mile run to its confluence with the COLORADO RIVER near Utah, the Dolores is a gateway to truly world-class scenery. Like its neighbor, the SAN MIGUEL, the headwaters of the Dolores River and West Dolores River are also in the San Juan Mountains, but both branches flow southwest before converging just above the town of Dolores. McPhee Reservoir, where Dolores River waters are held for agriculture, is located just southwest of the town. And from there, the Dolores meets a fate shared by many rivers in the West, as every drop is allocated to agricultural production. While some reservoirs help buffer fluctuations in water availability between wet and dry years, that isn’t the case for the Dolores. Despite being the second largest reservoir in Colorado, McPhee Reservoir doesn’t have the storage capacity to store enough water to satisfy both agricultural rights and flows for recreation and endangered fish.

Water released from the dam flows sharply northwest through Ponderosa and Slickrock Canyons, uniting with the San Miguel before flowing through the Paradox Valley and, ultimately, through Gateway Canyon and into the Colorado River.

When water is released, nearly 170 miles of it are floatable. In 2016, the Dolores River ran for the first time in five years. A healthy winter snowpack translated to some short-lived and well-celebrated releases that allowed for boating through the amazing Dolores River Canyon. On the rare opportunity to float, paddlers marvel at the towering sandstone walls, the regular encounters with beavers, the unique way floating the Dolores becomes paddling through coyote brush and tamarisk. Because high water flows are such a rare occurrence, campsites are overgrown and under established.

Since 1968 when initial construction on the McPhee Dam began, stakeholders in the region have worked to develop river management plans that support the river’s cold water fish species, alongside agricultural irrigation and the desire for recreation flows. The reservoir was completed in 1984, and in 1990, a dry summer limited flows from McPhee to less than 20 CFS, resulting in a major kill of cold water fish. Even lower summer flows have been recorded in recent years, killing native fish, destroying the geomorphology of the channel, shorting irrigators and the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, and stressing wildlife.

WILD AND SCENIC ELIGIBILITY

In both 1976 and again in 2013, the Dolores River was found suitable for designation under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act by the U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management, giving the Dolores River administrative protections for its free-flowing character and outstanding values. After a lengthy negotiation process, language in the Dolores River National Conservation Area bill would trade away Wild and Scenic suitability for similar protections of the river’s free-flowing character and outstanding values within the National Conservation Area (NCA) and Special Management Area (SMA). However, this would not preclude designating the Dolores River or its tributaries under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act in the future it there is social and political support for such a designation.

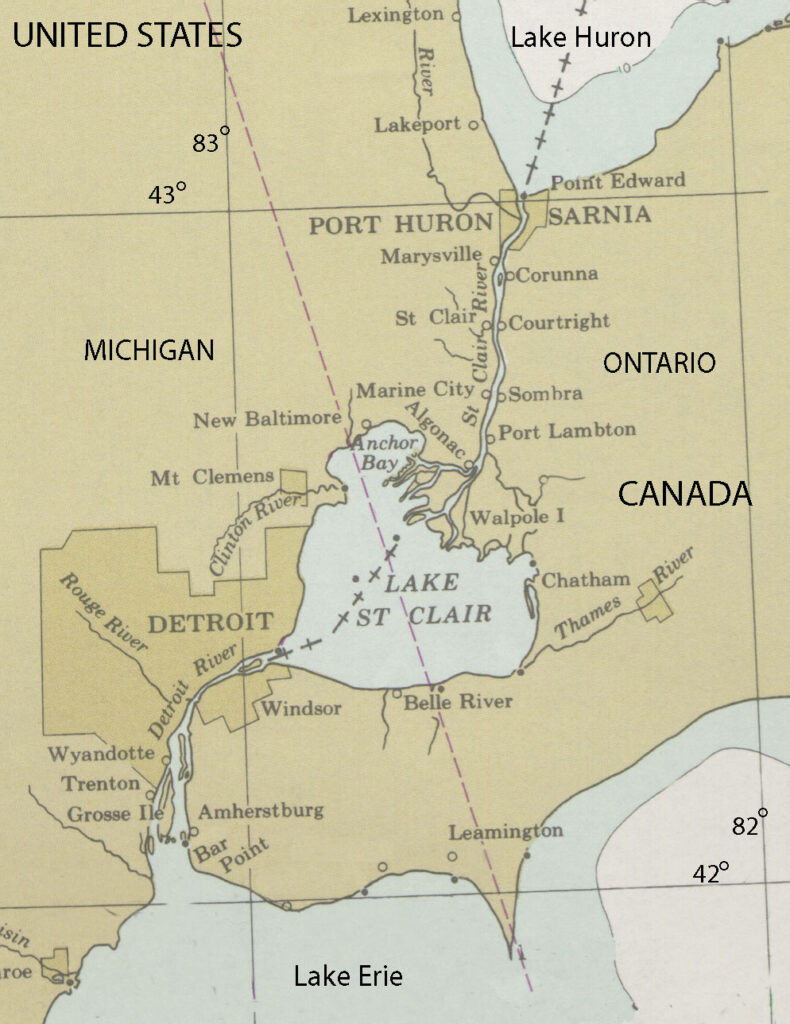

Detroit River

urbanization and the river

In the early 1900s, Detroit became one of the largest cities in the United States, and the Detroit River played a major role.

The river is 28 miles long and serves as the international border between Canada and the United States, connecting Lake St. Clair and the Upper Great Lakes to Lake Erie, and is one of the busiest waterways in the world. Heavy traffic and the urbanization on its shores led the Detroit River to become very polluted.

In recent years, though, local environmental groups have been working to reverse this trend, coordinating plans to clean up the river, and similar initiatives are being undertaken by American Rivers in locations across the Great Lakes region. These efforts are helping to reduce urban pollution and preserve these incredibly important natural resources for future generations.

On September 11, 1997, the Detroit River was named as one of 14 American Heritage Rivers by President Bill Clinton. These rivers were selected because local communities had specific plans in place to restore the environment, revitalize the economy, renew the culture, and preserve the history of their rivers. Since being designated, things have been looking up for the Detroit River.

Threats to This River

The Detroit River helped Detroit, the nation’s auto manufacturing hub, grow to become the country’s fifth largest city in 1950, but this enormous urban center led to problems with pollution, and the river suffered. According to the EPA, the river has faced 11 beneficial use impairments, including beach closings, restrictions on water consumption, and loss of fish and wildlife habitat.

These impairments are caused by bacteria, PCBs, PAHs, metals, and oils and greases entering the watershed, coming from municipal and industrial discharge and urban runoff, among other means. The contaminated river was undrinkable and virtually uninhabitable for many types of wildlife, but cleanup efforts that are now in place have made the Detroit River suitable for human and animal use once again.

A number of animals have returned to the Detroit River over the last few years, including sturgeon, whitefish, peregrine falcons, bald eagles, walleyes, and most recently beavers, which had not been seen in the river for 75 to 100 years. The fact that the river is providing adequate habitat for all of these species is clearly a sign of progress, and suggests the Detroit River is returning to health.

Urban runoff has been a big problem in Detroit, as 7.8 billion to 18.2 billion gallons of rainwater run off the land instead of being absorbed by it each year, but local efforts to make the city green, such as green roof construction and promoting urban farming, are helping reduce pollutants entering the water supply.

Desolation – Gray Canyons of the Green River

For 84 sinuous miles, the Green River of eastern Utah carves its way through one of the largest roadless areas in the lower 48 states, forming the remote and rugged country of Desolation and Gray canyons as it cuts through the Tavaputs Plateau. Desolation Canyon was so named when, in 1869, John Wesley Powell first chronicled the river’s nearly 60 side canyons, describing the journey as one through “a region of wildest desolation.”

Desolation Canyon

Remote and spectacular, Desolation Canyon has been home to Fremont People, their stories left behind in the pictographs, petroglyphs, and ancient dwellings, towers and granaries that still decorate the canyon’s walls. Since time immemorial, the Desolation Canyon region has also been home to the Ute Indian Tribe, whose Uintah and Ouray Reservation borders the east side of the river from above Sand Wash to Coal Creek Canyon, or 70 miles of Desolation/Gray Canyons.

Now, boaters of all persuasions relish multi-day river trips through relatively easy riffles and rapids, where sandy beaches with massive Fremont cottonwoods provide shade and cover from wind. The piñon, juniper and douglas fir-covered slopes of the canyon harbor wintering deer and elk, nesting waterfowl, bison, mountain lions, migrating birds and the occasional sun-bleached blackbear. Of the 84 river miles, 66 miles are within the Desolation Canyon Wilderness Study Area, the largest WSA in the lower 48 states. Looking up from the river, the edge of the canyon is nearly 5,000 feet overhead , and anywhere from 2-150 million years old. Of the canyon’s unique and exposed geologic history, celebrated southwest writer Ellen Meloy wrote: “You launch in mammals and end up in sharks and oysters.”

DID you know?

There are more than 60 rapids on the Desolation – Gray stretch of the Green River, ranging from class I-III

Edward Abbey floated the Green in November 1980 and described it as “one of the sweetest, brightest, grandest, loneliest of primitive regions still remaining”

In 2019, 63 miles of the Green River (including Labyrinth Canyon and the last 5.3 miles of Deso/Gray) were designated as a Wild & Scenic River in the Emery County Public Land Management Act.

What states does the river cross?

Utah

how can i help?

Our public lands, and by extension our last, best, wild rivers, are under threat.

Tell the Trump Administration to retain and support the Waters of the United States rule under the Clean Water Act. Take action here.

Eat locally – locally grown food cuts down on transportation, reducing our demand for oil and gas, and reduces the need for more drilling on public lands.

Stay informed with what is going on with rivers across the Southwest by following our Southwest River Protection Program. ] and signing up to receive action alerts. Early in 2021, the Comprehensive River Management Plan (CRMP) for the portion of the Green River that was designated as Wild and Scenic in 2019 will begin, and American Rivers will be working with BLM on the effort. We would love your help!

THREATS

While it’s true that Desolation Canyon remains one of the most remote places in the contiguous United States, the threats it faces are not so remote. And ironically, the canyon’s deep and layered history and geology in some ways, threaten the river most. The Green River Formation, formed between 33-56 million years ago, is a much sought after petroleum resource. A recent report by the USGS posited that the formation could hold as much as 1.3 trillion barrels of oil. In order to convert tar sands and oil shale into usable oil (1.55 million barrels/day), producers would require about 378,000 acre feet of water per/year, likely from the Green. While the inner gorge of Desolation Canyon is a designated wilderness study area, on the state, tribal, and federal lands surrounding it, oil rigs march right to the canyon’s edge.

The canyon’s existing protections are tenuous at best. In 2019, 142,996 acres were designated as the Desolation Wilderness in the Dingell Act, and 5.3 miles of Desolation-Gray from the Ute Reservation boundary to the take-out were designated under the Wild & Scenic Rivers Act. While this is a good start, 78.6 miles of the river remain lacking permanent protections.

Like so many rivers in the Colorado River Basin, the Green is subject to threats from persistent drought, climate change, and increased consumption from a growing population.

Let’s Stay In Touch Image: Anthracite Creek, Co. | Sinjin Eberle

Ashley River

SOUTH CAROLINA’S BLACK PEARL

From its slender Cypress Swamp origins to the wide salt marshes of the South Carolina low country, the Ashley River is the embodiment of southern charm rolled into a brackish package of history and recreation.

Dolphins make their way up the 30-mile stream from the Cooper River confluence at Charleston Harbor, fishing for striped bass, redfish, and speckled trout alongside anglers, kayakers, and canoeists paddling the Blue Trail that winds its way from the Ashley’s blackwater beginnings near Summerville past 26 separate sites listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

Paddlers can ride the tide in both directions if they time it right, leisurely taking in sights that include plantations predating the Revolutionary War and a diverse array of wildlife found along 22 miles designated as a State Scenic River.

The serene beauty of the upper Ashley offers refuge to deer and spectacular swallowtail kites as the river flows into the rapidly developing Charleston metro area and the saltwater ecosystem surrounding it. Bald eagles, osprey, and other birds of prey can be found along the river corridor, while lanky wading birds like egrets and great blue herons hunt the broad downstream marshes where redfish (locally known as spot-tailed bass) are more abundant. Endangered sturgeon can also be found making their way upstream to spawn.

Did You know?

The Ashley River is the “birthplace” of Charleston. In 1670, Charles Towne Landing was the first settlement on the Ashley, eventually becoming the city of Charleston.

Local lore holds that the Atlantic Ocean is formed at the confluence of the Ashley and Cooper rivers in Charleston Harbor.

The Ashley is one of 10 State Scenic Rivers established by South Carolina State Scenic Rivers Act of 1989.

What states does the river cross?

South Carolina

The Backstory

The Ashley River’s historical, cultural, and natural significance to South Carolina cannot be overstated. The river mouth served as the site of the state’s first permanent European settlement in the late 1600s and plantation owners began developing the upstream land along the river a century later. The river remains home to fish and wildlife, scenic landscapes, and opportunities for families to enjoy time together outside.

In 1992, the state’s Office of Coastal Resource Management worked with local communities to create the Ashley River Special Area Management Plan with the goal of preserving the river’s natural and historic character. In 1998, a portion of the river was designated as a State Scenic River in an effort to further protect its outstanding qualities. A second portion was added in 1999.

Today, the Ashley is part of one of the most rapidly growing regions in the United States. As a result, it is even more imperative to work now to promote and preserve the Ashley River as an easily accessible recreational oasis offering countless physical, mental, spiritual, and economic benefits.

The Future

The Ashley is a river at a crossroads right now. The ongoing threat of urban development is rapidly increasing as Charleston’s popularity as a community and top tourist destination continues to gain momentum and creep farther up the river corridor. Wisely planned growth is critical to the area and the Ashley River headwaters in particular.

Toward that end, plans for developing riverfront parkland, access points, special events, and programming that showcase the recreational value of the Ashley River figure prominently into Dorchester County’s current effort to create its first ever park system. Recently, American Rivers worked with local communities to create the Ashley River Blue Trail as a way to help those communities engage in the river and develop a vision for what it should look like in the future.

A Blue Trail is a river adopted by a local community that is dedicated to conserving riverside land and improving family-friendly recreation like fishing, boating, and wildlife-watching. Just as hiking trails are designed to help people explore the land, Blue Trails help people discover their rivers. They help communities improve recreation and tourism, benefit local businesses and the economy, and protect river health and wildlife. They are voluntary, cooperative, locally-led efforts that improve communities’ quality of life.