Klamath River

Klamath River Named as 2024 River of the Year

American Rivers announced that Oregon and California’s Klamath River is the 2024 River of the Year, celebrating the biggest dam removal and river restoration in history. The River of the Year honor recognizes significant progress and achievement in improving a river’s health.

“On the Klamath, the dams are falling, the water is flowing, and the river is healing,” said Tom Kiernan, President and CEO of American Rivers. “The Klamath is proof that at a time when our politics are polarized and the reality of climate change is daunting, we can overcome seemingly insurmountable challenges and make incredible progress by working together. This is why American Rivers is naming the Klamath the River of the Year for 2024.”

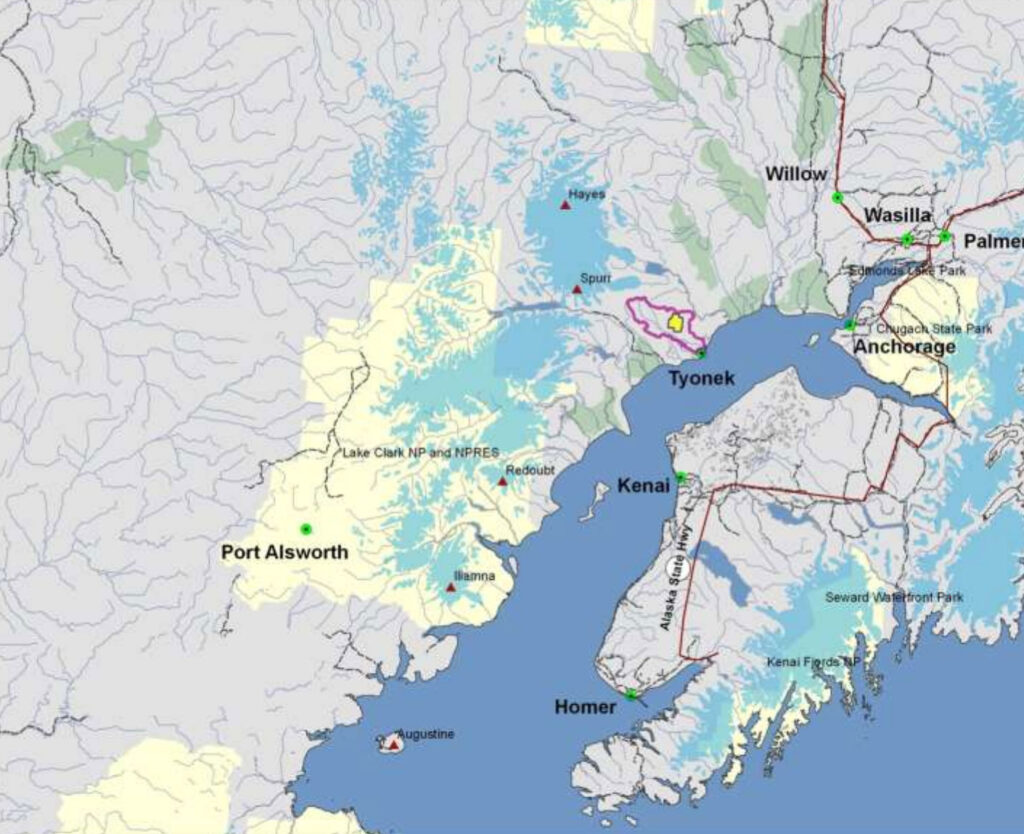

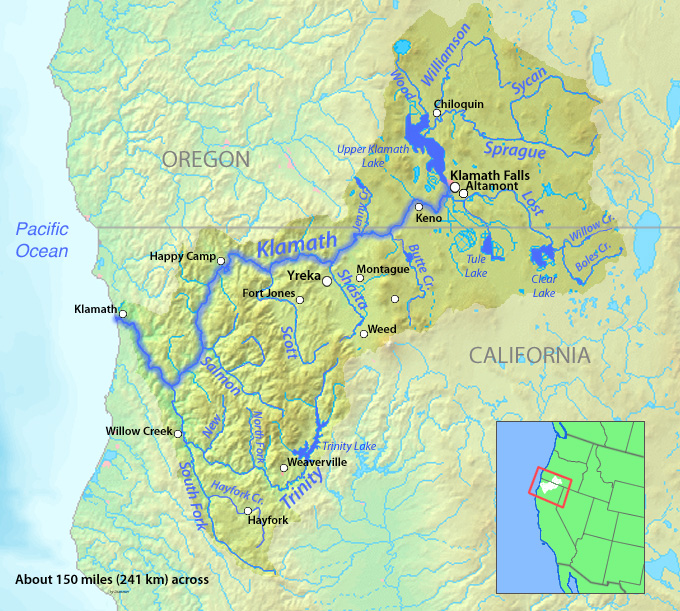

The Klamath River flows from a broad patchwork of lakes and marshes at the foot of the Cascade Mountains on the California-Oregon border and winds southwest into California. After passing through five hydropower dams, the river reaches the Pacific Ocean south of the fishing community of Crescent City.

The river has been home to indigenous people for thousands of years and tribes including the Yurok, Karuk, Hoopa, Shasta, and Klamath rely on, and care for, the river today.

Klamath River salmon runs were once the third-largest in the nation, but have fallen to just eight percent of their historic numbers. Chinook and coho salmon, steelhead and coastal cutthroat trout, green and white sturgeon, and Pacific lamprey all rely on the Klamath.

More than 75 percent of birds migrating on the Pacific Flyway feed or rest in the upper basin and the largest population of bald eagles in the lower 48 states winters in several national wildlife refuges there.

The Upper Basin

The upper Klamath basin has been called the “Everglades of the West.” However, almost 80 percent of the upper basin’s wetlands have been converted to grow thirsty crops such as potatoes, alfalfa, and hay, including nearly 23,000 acres on the Tule Lake and Lower Klamath National Wildlife Refuges. Irrigation withdrawals and polluted farm runoff have harmed the river and its fisheries.

Thanks to the efforts of our partners, MANY PROJECTS have been completed or are currently underway that are designed to improve water quality and fish habitat while making it easier for landowners to meet water quality goals that both satisfy regulators and ensure healthy water supplies for people and wildlife.

Did You know?

The Southern Oregon/Northern California Coast coho is federally listed as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act.

Low water flows in September 2002, led to the death of an estimated 34,000-70,000 chinook, coho, and steelhead on the Klamath, making it the largest salmon kill in the history of the American West.

With 286 miles classified as wild, scenic, or recreational, the Klamath is the longest Wild and Scenic River in California. Another 11 miles of the upper Klamath are designated in Oregon.

The Klamath River watershed is as big as Massachusetts and Connecticut combined.

What states does the river cross?

California, Oregon

Guardians of the River

In this film by American Rivers and Swiftwater Films, Indigenous leaders share why removing four dams to restore a healthy Klamath River is critical for clean water, food sovereignty, and justice.

Watch: ‘Voices of the Klamath’ shorts

Klamath River Dams

The original Klamath River agreements were crafted through the leadership of Tribes in the basin who came together with American Rivers and other conservation organizations, PacifiCorp, state and federal agencies, commercial fishing representatives, and members of the agricultural community to remove the dams, restore habitat and resolve decades-long water management disputes.

Dam removal will restore access to more than 300 miles of habitat for salmon. It will also improve water quality – currently, toxic algae in the reservoirs behind the dams threaten the health of people as well as fish.

Why is removing a dam important for a river’s healing? Dr. Ann Willis, California Regional Director at American Rivers, answers this question in front of one of 4 dams that will be removed as part of the largest dam removal project in history underway now on the Klamath River.

How does dam removal support communities? Dr. Ann Willis joins us from Iron Gate Dam on the Klamath River to reflect on the benefits of dam removal for salmon, clean water, Tribal Nations, and climate resilience.

But perhaps more important than the size of the dams is the amount of collaboration and the decades of hard work that have made this project possible. American Rivers has been fighting to remove the dams since 2000. Thanks to the combined efforts of the Karuk and Yurok tribes, irrigators, commercial fishing interests, conservationists, and many others, our goal of a healthy, free-flowing river is now within reach.

The Klamath River Renewal Corporation is managing the dam removal project.

Catawba River

once wild

Spanning two states and more than 200 miles, the Catawba is more a linked series of reservoirs than a genuine river anymore.

This once-wild waterway named for the Catawba tribe of Indigenous People — “the people of the river” — rises in the Blue Ridge Mountains just east of Asheville, NC, and yields for no fewer than 11 impoundments on its way to and through South Carolina, where it eventually becomes known as the Wateree River before landing in Congaree National Park for its final 10 miles above Lake Marion.

Along the way, it weaves through some of the finest countrysides in the Carolinas, alternating between rural and urban landscapes, and passes by densely populated Charlotte, where it forms the 33,000-acre Lake Norman, a mecca of outdoor recreation.

The 30-mile stretch of the Catawba River between the Lake Wylie Hydro Station and the upper end of Fishing Creek Lake is now the longest portion of the Catawba River that remains undammed, forming a significant portion of the Wateree Blue Trail that winds 75 miles south to meet the Congaree River Blue Trail within the national park. The land bordering much of the Catawba-Wateree along the Blue Trail remains a wooded and natural floodplain forest, creating a haven for bald eagles, river otters, belted kingfishers, and wildlife of all sorts.

The Catawba River is also rich in history, providing for ancestors of the Catawba Indian Nation for some 12,000 years. European explorers and early American settlers eventually found their way to the valley and continue to flock to the region, all leaving their mark on the river. The basin is one of a precious few areas left in the southeast with significant populations of the rocky shoals spider lily (Hymenocallis coronaria), with notably the world’s largest population left at Landsford Canal State Park.

THE BACKSTORY

Beginning in 1904, a series of hydroelectric dams were constructed to harness the power of the river in an effort to foster growth in the region and meet increasing demands for energy. The hydro station forming Lake Wylie was the cornerstone of what is now Duke Energy, the largest electric power company in the U.S.

More than two million people now live in the Catawba-Wateree basin, and rapid growth is putting a strain on water resources. The lack of an overall plan for efficient water use is one of the reasons why American Rivers named the Catawba River one of America’s Most Endangered Rivers® in 2008. In 2010, the Southern Environmental Law Center (SELC) named the Catawba-Wateree basin one of the top 10 most endangered places in the Southeast for the same reason. The Catawba Wateree Water Management Group has been focused on addressing some of the issues around water management that was highlighted by the droughts from 2007-2009 and the pressures of a growing population.

Did You know?

The Catawba River changes its name to the Wateree near the flooded confluence of Wateree Creek, reflecting the name of the native American tribes that inhabited the various regions of the river.

The Wateree River joins the Congaree River at Congaree National Park, forming the Santee River that eventually makes its way to the Atlantic Ocean.

The 30-mile section of the Catawba River downstream from Lake Wylie dam was designated a South Carolina State Scenic River in June 2008.

The section of the Catawba passing through Landsford Canal State Park is known for its large stand of rocky shoals spider lily, which has a spectacular bloom in mid-May to mid-June that may be viewed by boat or on foot.

WHAT STATES DOES THE RIVER CROSS?

North Carolina, South Carolina

The river’s 11 hydroelectric dams combined with drought, climate change, and rampant development contribute to a variety of issues—including flow management, polluted runoff, and industrial waste—that continue to pose significant risk to the health of the river and the people that depend on it.

The tributary rivers that flow into the Catawba are littered with legacy small dams that powered the textile industry of the region but have now fallen into disrepair. Most of these dams have outlived their useful lives and now are just ecological and community liabilities. We have worked with some communities- like Hickory, NC on the Henry Fork- to remove some of these dams to restore the river and improve recreational and economic activities and there are many more such stories to come.

Coal ash, a byproduct of power generation, has historically threatened the river and local water supply with pollution. In 2020, the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality approved a suite of plans to close and excavate the coal ash move it to lined landfills or recycle it for beneficial use. This was a great victory for improving the health of the Catawba River.

The Future

It has been more than 100 years since the town of Great Falls, South Carolina has lived up to its name. But a landmark hydropower operating license has restored continuous flows to areas that have been bypassed since Duke’s Great Falls Hydro and reservoir were built in the early 1900s. In 2022, the new license will restore flows to whitewater rapids, create kayak and raft launches, and provide fishing areas with hopes of introducing ecotourism to the economically struggling town. Special whitewater releases are planned in the late spring and summer for visitors to enjoy.

Duke Energy’s relicensing process was the biggest hydroelectric dam relicensing in the nation, and the outcomes are leading to great improvements to the health of the river by dramatically altering reservoir operations, providing continuous river flows, enhancing water quality and reshaping how people use and value the river for the next half century. The new, 40 year license will improve the entire river system.

The FERC relicensing is reflective of modern conservation values and returns water to five sections of the Catawba-Wateree by establishing continuous flow requirements rather than daily averages, where the river could essentially be turned off and on in order to meet requirements. Some improvements are already being implemented, putting water back in the river channel where it historically has been redirected to generate electricity or cool power stations. That translates to improved recreational access as well as general river health for people, fish and wildlife, including endangered sturgeon and other fish species that make their home in the Catawba-Wateree river system.

Population growth and a changing climate are requiring new strategies for addressing water management in the basin. The most effective way of addressing them is through an integrated water management approach that protects critical areas of the watershed, invests in improved water delivery and treatment systems, and manages stormwater as a resource while restoring floodplains to better store excessive water filtering it and slowly releasing it back to the streams and rivers.

There are hundreds of dams in the watershed that are ripe for removal. We have been building a team of restoration specialist who can work with their communities to address these liability and support the removal of the unnecessary dams.

Chuitna River

The wild Chuitna River winds for 25 miles from the base of the Tordrillo Mountains to Cook Inlet.

The river’s pristine waters are the lifeblood of the region, emblematic of true Alaskan wilderness. In a world where most salmon runs have been depleted and destroyed, the Chuitna boasts abundant runs of all five species of wild Pacific salmon.

These prolific salmon runs support a significant subsistence, recreational, and commercial fishery, and are an essential source of nourishment for humans and wildlife in this region.

The Chuitna is bordered by two communities: Tyonek, a Native community, and Beluga, a frontier outpost. These communities rely on the river’s salmon, moose, and waterfowl populations for subsistence, and the average resident harvests roughly 200 pounds of fish and meat annually. Additionally, these communities are home to a number of commercial fishermen whose top-quality salmon are sold across the nation. Studies have demonstrated that the potential costs of the mine in the form of lost economic opportunity and environmental damage would exceed the potential benefits by a staggering rate of $3 to $6 in costs for every dollar of revenue generated.

Threats To This River

The Chuitna River is threatened by PacRim Coal’s proposed Chuitna Mine. If approved, the project would carve a 300-foot deep pit through 13.7 miles of the Chuitna’s headwater streams. It would be one of our nation’s largest open-pit coal mines and would destroy 30 square miles of irreplaceable wild river habitat. The project would be the first in Alaska to mine directly through a wild salmon stream, setting a dangerous precedent that could endanger hundreds of other wild Alaskan rivers. Additionally, the project would irrevocably harm thousands of acres of wetlands, forests, and bogs that play an important role in maintaining the Chuitna River’s water quality and serve as important habitat for bears, moose, upland birds, and waterfowl.

Adjacent areas not directly strip mined by PacRim would be inundated with 7 million gallons of mine waste every day. This waste would flow into the Chuitna River and subsequently the Cook Inlet, creating a toxic trail that would harm a wide array of fish and other wildlife, including the endangered Beluga whale.

Making matters worse is PacRim’s plan to construct a large export facility that would ship the Chuitna’s low-grade coal exclusively to Asian markets. This infrastructure would include a two-mile-long trestle into Cook Inlet, cutting off the natural migration patterns of salmon and Beluga whales.

Of even greater concern, this infrastructure would enable PacRim and other companies to act on existing coal leases that are currently uneconomical due to shipping limitations, potentially opening up the entire 33 billion-ton Susitna-Beluga coal field and decimating some of Alaska’s most wild and pristine rivers.

Colorado River

The beating heart of the American Southwest

From its genesis on the Continental Divide in Colorado’s Rocky Mountain National Park, the river originally known as the Grand grows from a cold mountain trout stream into a classic Western waterway slicing through jagged gorges between sweeping, pastoral ranchlands on the upper leg of a 1,450-mile journey.

Its stature continues to swell as it carves through some of the planet’s most iconic landscapes—desert canyons, buttes, and mesas—before being bottled up and sucked dry by agriculture and municipal demand. Its once-mighty flow ends, in fact, several miles shy of the Gulf of California in Mexico.

Even the Colorado’s signature attraction—the awe-inspiring Grand Canyon—wasn’t recognized as a national monument by President Teddy Roosevelt until 1908 and a national park 11 years later. But the once-lonely river began attracting attention soon after a series of mid-century hydraulic-engineering projects overtook the basin that today quenches the thirst of some 36 million people. The 277-mile segment of river passing through the Grand Canyon is bracketed by the two largest storage impoundments in the nation—Lake Powell and Lake Mead—required to fulfill an insatiable demand on the resource.

The hardest working river in the West is as diverse as it is unique. Passing through no less than 11 different national parks and monuments as it tumbles through the varied landscapes of seven states and two countries, it’s a critical water supply for agriculture, industry, and municipalities, from Denver to Tijuana, which fuels a $1.4 trillion annual economy. Fishing, whitewater paddling, boating, backpacking, wildlife viewing, hiking, and myriad other recreational opportunities contribute some $26 billion alone.

The Backstory

As famous as the Colorado may be, it’s equally infamous for the stresses placed upon it due to over-allocation, overuse, and more than a century of manipulation. The watershed spanning a remarkable 8 percent of the continental U.S. funnels into the sixth-longest river in the nation, yet overestimations of the river’s bounty when the Colorado River Water Compact was ratified back in 1922 established a bank account destined to be permanently overdrawn.

Following decades of wasteful water management policies and practices, demand on the river’s water now exceeds its supply, and storage levels at Lake Powell and Lake Mead are critically low. More dams and diversions are planned, particularly in the upper basin in Colorado, where 50 percent of the headwater flows are already diverted east of the Continental Divide.

Did You know?

At 1,450 miles long, the Colorado River is the sixth longest in the nation, passing through seven states and two nations.

The Colorado basin spans 260,000 square miles, about 8 percent of the continental U.S.

The river flows through 11 national parks and monuments.

The Grand Canyon is one of the Eight Natural Wonders of the World and a Unesco World Heritage Site.

The Grand Canyon is about 277 river miles long, but requires about 650 miles to walk.

The Colorado River Water Compact drafted in 1922 to divide water between upper and lower basin states was based on analysis of one of the wettest 10-year periods in history, establishing a permanent deficit.

A third of the entire Latino population in the U.S. lives in the Colorado basin.

WHAT STATES DOES THE RIVER CROSS?

Arizona, California, Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah, Wyoming

EXPLORE THE COLORADO BASIN

The Lower Colorado River, which provides water to Las Vegas, Los Angeles, San Diego, Phoenix, and Tucson, already faces a one million acre-foot deficit and is in danger of running dry far before the Pacific. Climate change is expected to further reduce the river’s flow by 10 to 30 percent by 2050.

The battery of threats facing the natural masterpiece the river has carved through the Grand Canyon have earned that segment the number one spot on American Rivers’ Most Endangered Rivers® report in 2015. Insults menace from all sides: a proposed industrial-scale construction project reaching into the sacred heart of the canyon, radioactive pollution from uranium mining, and an expansion of groundwater pumping if a massive potential development on the south rim goes through. These things threaten the Grand Canyon’s wild nature and the profound experience that belongs to every American.

The Future

There is still hope for the Colorado, and even a few success stories. Our partners at Western Resource Advocates have identified five things we can do right now that would save 4.4 million acre-feet of water in the Colorado River basin while protecting the West’s recreational economy even in drought years.

By expanding municipal water conservation through improved landscaping and water-saving appliances, increasing municipal water re-use, improving agricultural efficiency and water banking, escalating renewable energy (wind, solar, geothermal, and thermoelectric), and implementing innovative water saving opportunities such as removing invasive plants along the river, reducing dust on snow that increases evaporation, and targeted desalinization of inland groundwater, we can exceed anticipated water demand through 2060.

The City of Tucson already has implemented a substantial water conservation program leading to a nearly 40-year surplus of recharged groundwater supply for the city even if water drops below critical levels in Lake Mead. The recently developed Colorado Water Plan identified key goals to achieve in the next few years that will keep the growing population hydrated until 2050 while prioritizing the health of rivers, including the Colorado.

And in the Grand Canyon, public outcry dealt a major setback to the South Rim development proposal at Tusayan, with the vast majority of about 230,000 comments received by the U.S. Forest Service during a recent scoping period leading to a permit denial. Likewise, the Obama administration has instituted a 20-year moratorium on new leases for uranium mining on the canyon rim, although it does not apply to legacy mines.

Plenty of work remains to be done. But a renewed appreciation and focused efforts on enhancing the resource may yet write the pivotal chapter in the story of the great Western treasure that is the Colorado River.

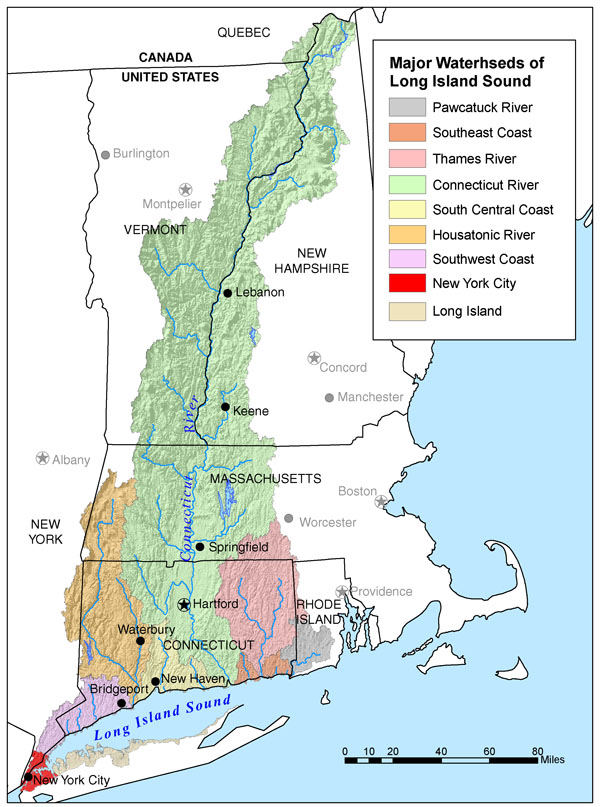

Connecticut River

NEW ENGLAND STRONG

New Englanders take great pride in the region’s longest river, and they should. Wild, natural scenery abounds along the 410-mile Connecticut River, which is heralded as the first—and only—National Blueway designated under the America’s Great Outdoors initiative by the Obama administration in 2012. The program was dismantled in 2014, but the national landmark that is the Connecticut River endures.

The river that flows from the Canadian border to the Long Island Sound in Connecticut didn’t always merit such lofty praise. Once described as America’s “best landscaped sewer,” the Connecticut has largely rebounded from hard times and today provides drinking water for millions and supports recreational uses, important fisheries, and healthy landscapes. The river and its tributaries have received several federal designations for their wild and scenic nature and importance to the region’s cultural heritage.

With a watershed that includes more than 2.4 million residents spread across some 400 communities, the Connecticut means much to many. Outstanding boating opportunities range from kayaking and quiet water boating on its more placid reaches to whitewater paddling on tributaries like the Deerfield, Farmington, and West rivers, extending downriver to heavy motor traffic between the town of Essex and the river mouth. Due to the heavy silt loads carried by the river that obstruct ship navigation, the Connecticut is one of the few major rivers in the United States without a major city at its mouth. Its largest cities—Hartford and Springfield—lie 45 and 69 miles upriver, respectively.

Abundant cold-water habitat throughout the watershed provides great opportunities for fishing, and several species of fish—both resident and migratory—can be found, including brook trout, winter flounder, blueback herring, alewife, rainbow trout, large brown trout, American shad, hickory shad, smallmouth bass, Atlantic sturgeon, and striped bass. After an absence of more than 200 years, Atlantic salmon have been reintroduced to the Connecticut by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Meanwhile, lake trout and landlocked salmon reside in the upper river surrounding the Connecticut Lakes.

The Silvio O. Conte National Fish and Wildlife Refuge serves as a cornerstone of the fishery and surrounding ecosystem since 1997. Located within parts of four New England states—New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, and Connecticut—the 36,000-acre refuge, named for its championing Congressman, is the only refuge of its kind to encompass an entire watershed. Its creators recognized the need to protect the whole river system and its wide variety of unique habitats ranging from northern forest to salt marshes in order to protect migratory fish and other species dependent upon the Connecticut River corridor.

Did You know?

The Connecticut River was designated the first National Blueway under the America’s Great Outdoors Initiative by the Obama administration in 2012.

As testament to its watershed-wide mission, the Silvio O. Conte National Fish and Wildlife Refuge is one of only three refuges in the National Wildlife Refuge System that has “Fish” in its title.

In 1997, the Connecticut River was designated one of only 14 American Heritage Rivers in recognition of its “distinctive natural, economic, agricultural, scenic, historic, cultural, and recreational qualities.”

WHAT STATES DOES THE RIVER CROSS?

Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Vermont

The Backstory

The history of the Connecticut River can be told through dams. New England communities were built along the banks of rivers and dams have been a central component since the beginning to provide water for irrigation, power generation, industrial operations, and drinking. The Connecticut remains among the most extensively dammed rivers in the nation.

Many of those dams are now obsolete. Yet more than 3,000 of these obstructions still impound the tributaries of the Connecticut River, with adverse impacts on river health, flooding, local economies, and community quality of life. The river’s great anadromous fish runs have suffered extensively through years of obstruction and warm-water discharges extending for miles below the Vermont Yankee Nuclear Power Plant in Vernon, VT. Downstream in South Hadley Falls, MA, American shad declined by 80 percent between 1992 and 2005, as measured at the Holyoke Dam.

Road-stream crossings are another longstanding challenge within the watershed, which contains more than 44,000 crossings. Many are undersized relative to stream size. Ideally, each crossing would mimic the natural stream banks and allow fish and wildlife to pass under while cars and travelers pass safely over. But the Connecticut’s undersized crossings are easily obstructed and prone to failure during large storms such as Tropical Storm Irene in 2011, when over 1,000 culverts and 500 bridges failed.

What’s New

American Rivers works hard to ensure that hydropower dams balance energy production and improve river health. There are five hydropower dams owned by FirstLight and Great River Hydro that are being relicensed for the next 40-50 years. These five dams dramatically impact the health of over 200 miles of the Connecticut River. We are actively working with state and federal agencies and our partners to ensure that these projects better support fish passage, river health, and better recreation infrastructure.

The Future

The Connecticut River has come a long way, but there are plenty more opportunities to improve river access for recreation, river connectivity, habitat restoration, and flows at the large hydro facilities throughout the corridor.

The river could soon flow at a more natural pace, should the computer-modeling efforts of scientists at the University of Massachusetts to coordinate water releases between the river’s 54 largest dams pay off. With the addition of fish ladders at multiple dams on the river, access to historic spawning habitat for anadromous fish is returning as well

Like much of New England, the watershed has more forested land today than it did 150 years ago. Combined with the cultural and recreational value of the river system, that natural landscape has helped major tributaries like the Eight Mile River, Farmington River, and Westfield River earn Wild and Scenic River designation, with potential for more on the horizon.

Building off the federal Connecticut River Blueway Designation, American Rivers is continuing to bring expertise in developing river recreation and protection opportunities to the watershed to engage with partners and help direct funding for these efforts.

Delaware River

LIFEBLOOD OF THE NORTHEAST

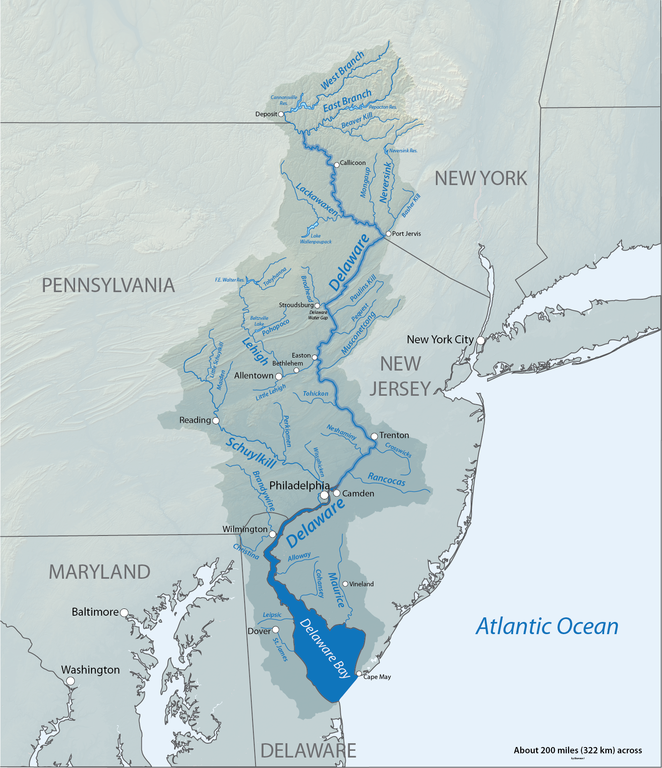

More than 17 million people get their drinking water from the Delaware River basin, including two of the five largest cities in the U.S.—New York City and Philadelphia. Any yet, the river offers so much more than a drinking water supply to the 42 counties and five states it passes through on its way to the Atlantic Ocean. Steeped in history, dripping with scenic beauty, and essential to the existence of some of the most significant communities along the Eastern seaboard, the Delaware River undeniably contributes its share to the lifeblood of the nation. From Gen. George Washington’s celebrated Revolutionary War crossing near Trenton, upstream to the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area and into the forests and farmlands of its headwaters, the river offers something for everyone.

The upper Delaware was an obvious choice as one of America’s first Wild and Scenic Rivers. Since 1978, the 73 miles downstream from the confluence of the East and West branches cascading out of the Catskill Mountains have been formally recognized for their natural appeal and recreation value. Undammed for the entire 330 miles of its main stem, the free-flowing character of the upper Delaware provides exceptionally clean water and superior ecological integrity that hosts wildlife in abundance. Mink, muskrat, beavers, white-tailed deer, wild turkeys, owls, bobcats, and otters all call the river valley home.

More than 200 avian species along the Atlantic Flyway rely on the upper Delaware, and the watershed hosts one of the largest populations of wintering bald eagles in the northeast. Great blue herons can sometimes be seen hunting American shad that travel unobstructed between the upper reaches of the river and the Atlantic Ocean. The urban Delaware River is home to globally rare freshwater tidal marshes and the nation’s first Urban National Wildlife Refuge and the Delaware Bay boasts the largest breeding population of horseshoe crabs in the world.

The Delaware River is well known for its fishing opportunities. Combined with its tributaries, the river supports more than 60 fish species—popular game fish like Eastern brook trout, striped bass, and migrating river herring among them. That’s a big part of the attraction for more than 500,000 people drawn to the Delaware annually to boat, camp, hunt, hike, watch wildlife, or just enjoy the scenery.

Did You know?

The Delaware Water Gap NRA was the result of a failed plan to build a dam on river at Tocks Island, just north of the Delaware Water Gap, for flood control and hydroelectric power. Due to environmental opposition and dwindling funds, the government transferred the property to the National Park Service in 1978.

George Washington’s army crossed the Delaware on the night of Dec. 25-26, 1776, for a successful surprise attack on the Hessian troops occupying Trenton, NJ, during the American Revolution.

The glowing neon sign across the river reading “Trenton Makes, the World Takes” originated from a 1910 Chamber of Commerce contest to sum up the city’s manufacturing virtues.

WHAT STATES DOES THE RIVER CROSS?

Delaware, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania

What’s New

NEW REPORT: A Study of Fair and Green Investments in the State Revolving Funds of the Delaware River Watershed.

New Along the Delaware stories highlighting infrastructure funding workshops for municipalities, and the Search for the Cooper River expedition. See the story map

Gateway Gardens: a new approach to stormwater management. Download the brochure.

NEW FACT SHEET: Infrastructure Funding Advocacy Tips for the Delaware River Watershed.

NEW GUIDE: Using Clean Water State Revolving Funds for Greening and Climate Resilience: A Guide for Municipalities.

For all of these reasons (and more!) the Delaware River is one of two priority river basins for American Rivers in the Mid-Atlantic region, and our 2020 River of the Year.

Despite successful conservation efforts across the Delaware River basin, the hard-working river has not been immune to the pressures of development. Impacts from logging and mining in the headwaters, commercial and industrial activity downstream, and the burdens of sprawling and increasingly dense populations all require considerable management to overcome. The cleanup of industrial pollution in the Delaware River and estuary have been recognized as one of the premier water pollution control success stories in the U.S. However, the impacts of development combined with the unpredictable threat of climate change continue to threaten this vibrant river system.

THE FUTURE

These days, tourism is the largest industry in the Upper Delaware region. For example, in Pike County, PA it provides jobs to 10 percent of the local population and $65 million to the local economy. In Sullivan County, NY, the year-round population more than triples on typical summer weekends, as folks seek out a place to play. Overall, the watershed contributes $22.5 billion a year to the economy from recreation, hunting and fishing, water quality and supply, ecotourism, forest, agriculture, open space, and port benefits.

The importance of connectivity remains a key part of the management plan, protecting headwater tributaries from the impacts of fracking as the river is restored downstream from historic mining damages. Tributary dam removal projects aim to further enhance water quality and potentially add to the watershed’s portfolio of more than 430 miles of Wild and Scenic River designation extending to the Maurice and Musconetcong Rivers in New Jersey, and the entire White Clay Creek in Pennsylvania and Delaware.

Smart and sustainable management will be required if the Delaware River is to remain resilient to the challenges of natural gas exploration, aging water infrastructure, continued urban development, and climate change. American Rivers intends to be part of the solution, collaborating with the entire conservation community to increase awareness and federal funding for restoration in the basin, employ innovative policy to improve water quality and habitat, and help boost recognition of the importance of a drinkable, fishable, and swimmable Delaware River by local residents.

ALONG THE DELAWARE

The Delaware River is an extraordinary example of restoration and a model for equitable and innovative clean water solutions. Hop on our five day tour of 2020’s River of the Year, highlighting local leaders and clean water solutions! LEARN MORE

Desolation – Gray Canyons of the Green River

For 84 sinuous miles, the Green River of eastern Utah carves its way through one of the largest roadless areas in the lower 48 states, forming the remote and rugged country of Desolation and Gray canyons as it cuts through the Tavaputs Plateau. Desolation Canyon was so named when, in 1869, John Wesley Powell first chronicled the river’s nearly 60 side canyons, describing the journey as one through “a region of wildest desolation.”

Desolation Canyon

Remote and spectacular, Desolation Canyon has been home to Fremont People, their stories left behind in the pictographs, petroglyphs, and ancient dwellings, towers and granaries that still decorate the canyon’s walls. Since time immemorial, the Desolation Canyon region has also been home to the Ute Indian Tribe, whose Uintah and Ouray Reservation borders the east side of the river from above Sand Wash to Coal Creek Canyon, or 70 miles of Desolation/Gray Canyons.

Now, boaters of all persuasions relish multi-day river trips through relatively easy riffles and rapids, where sandy beaches with massive Fremont cottonwoods provide shade and cover from wind. The piñon, juniper and douglas fir-covered slopes of the canyon harbor wintering deer and elk, nesting waterfowl, bison, mountain lions, migrating birds and the occasional sun-bleached blackbear. Of the 84 river miles, 66 miles are within the Desolation Canyon Wilderness Study Area, the largest WSA in the lower 48 states. Looking up from the river, the edge of the canyon is nearly 5,000 feet overhead , and anywhere from 2-150 million years old. Of the canyon’s unique and exposed geologic history, celebrated southwest writer Ellen Meloy wrote: “You launch in mammals and end up in sharks and oysters.”

DID you know?

There are more than 60 rapids on the Desolation – Gray stretch of the Green River, ranging from class I-III

Edward Abbey floated the Green in November 1980 and described it as “one of the sweetest, brightest, grandest, loneliest of primitive regions still remaining”

In 2019, 63 miles of the Green River (including Labyrinth Canyon and the last 5.3 miles of Deso/Gray) were designated as a Wild & Scenic River in the Emery County Public Land Management Act.

What states does the river cross?

Utah

how can i help?

Our public lands, and by extension our last, best, wild rivers, are under threat.

Tell the Trump Administration to retain and support the Waters of the United States rule under the Clean Water Act. Take action here.

Eat locally – locally grown food cuts down on transportation, reducing our demand for oil and gas, and reduces the need for more drilling on public lands.

Stay informed with what is going on with rivers across the Southwest by following our Southwest River Protection Program. ] and signing up to receive action alerts. Early in 2021, the Comprehensive River Management Plan (CRMP) for the portion of the Green River that was designated as Wild and Scenic in 2019 will begin, and American Rivers will be working with BLM on the effort. We would love your help!

THREATS

While it’s true that Desolation Canyon remains one of the most remote places in the contiguous United States, the threats it faces are not so remote. And ironically, the canyon’s deep and layered history and geology in some ways, threaten the river most. The Green River Formation, formed between 33-56 million years ago, is a much sought after petroleum resource. A recent report by the USGS posited that the formation could hold as much as 1.3 trillion barrels of oil. In order to convert tar sands and oil shale into usable oil (1.55 million barrels/day), producers would require about 378,000 acre feet of water per/year, likely from the Green. While the inner gorge of Desolation Canyon is a designated wilderness study area, on the state, tribal, and federal lands surrounding it, oil rigs march right to the canyon’s edge.

The canyon’s existing protections are tenuous at best. In 2019, 142,996 acres were designated as the Desolation Wilderness in the Dingell Act, and 5.3 miles of Desolation-Gray from the Ute Reservation boundary to the take-out were designated under the Wild & Scenic Rivers Act. While this is a good start, 78.6 miles of the river remain lacking permanent protections.

Like so many rivers in the Colorado River Basin, the Green is subject to threats from persistent drought, climate change, and increased consumption from a growing population.

Let’s Stay In Touch Image: Anthracite Creek, Co. | Sinjin Eberle

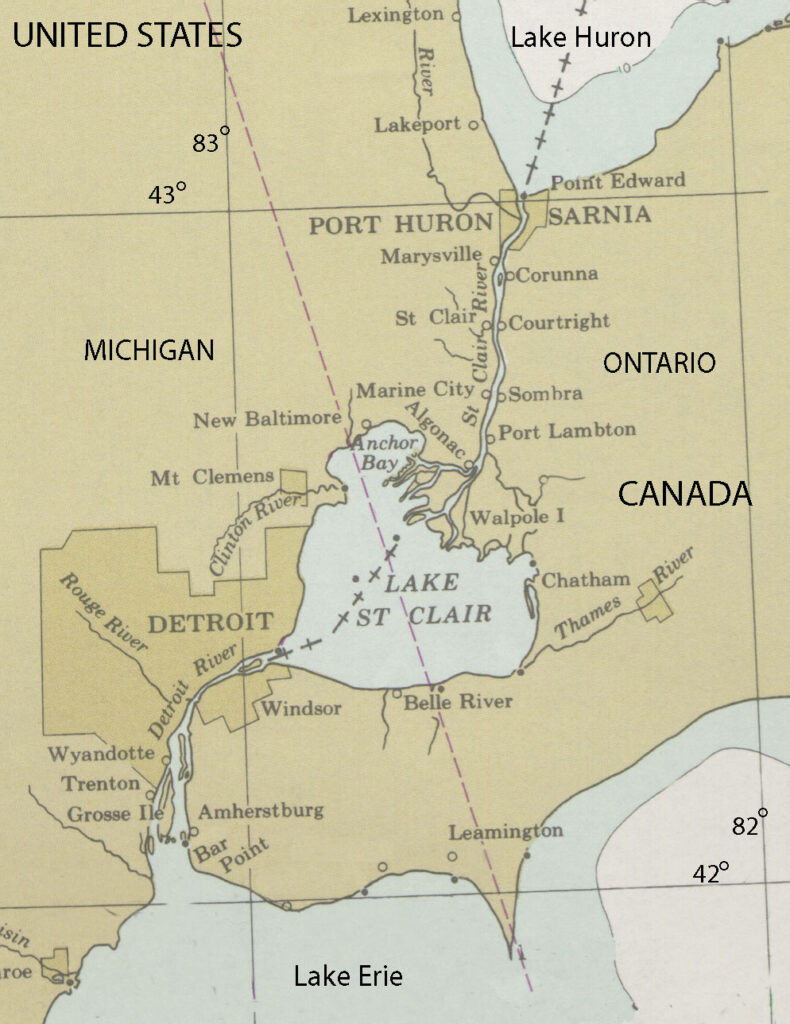

Detroit River

urbanization and the river

In the early 1900s, Detroit became one of the largest cities in the United States, and the Detroit River played a major role.

The river is 28 miles long and serves as the international border between Canada and the United States, connecting Lake St. Clair and the Upper Great Lakes to Lake Erie, and is one of the busiest waterways in the world. Heavy traffic and the urbanization on its shores led the Detroit River to become very polluted.

In recent years, though, local environmental groups have been working to reverse this trend, coordinating plans to clean up the river, and similar initiatives are being undertaken by American Rivers in locations across the Great Lakes region. These efforts are helping to reduce urban pollution and preserve these incredibly important natural resources for future generations.

On September 11, 1997, the Detroit River was named as one of 14 American Heritage Rivers by President Bill Clinton. These rivers were selected because local communities had specific plans in place to restore the environment, revitalize the economy, renew the culture, and preserve the history of their rivers. Since being designated, things have been looking up for the Detroit River.

Threats to This River

The Detroit River helped Detroit, the nation’s auto manufacturing hub, grow to become the country’s fifth largest city in 1950, but this enormous urban center led to problems with pollution, and the river suffered. According to the EPA, the river has faced 11 beneficial use impairments, including beach closings, restrictions on water consumption, and loss of fish and wildlife habitat.

These impairments are caused by bacteria, PCBs, PAHs, metals, and oils and greases entering the watershed, coming from municipal and industrial discharge and urban runoff, among other means. The contaminated river was undrinkable and virtually uninhabitable for many types of wildlife, but cleanup efforts that are now in place have made the Detroit River suitable for human and animal use once again.

A number of animals have returned to the Detroit River over the last few years, including sturgeon, whitefish, peregrine falcons, bald eagles, walleyes, and most recently beavers, which had not been seen in the river for 75 to 100 years. The fact that the river is providing adequate habitat for all of these species is clearly a sign of progress, and suggests the Detroit River is returning to health.

Urban runoff has been a big problem in Detroit, as 7.8 billion to 18.2 billion gallons of rainwater run off the land instead of being absorbed by it each year, but local efforts to make the city green, such as green roof construction and promoting urban farming, are helping reduce pollutants entering the water supply.

Dolores River

After nearly 20 years of collaborative work, Colorado Senator Michael Bennet introduced the Dolores River National Conservation Area and Special Management Area Act in July 2022. Colorado Senator John Hickenlooper co-sponsored the bill, and Colorado Congresswoman Lauren Boebert introduced companion legislation in the House, emphasizing the bipartisan nature of this proposal. The Act was introduced at the behest of Dolores, Montezuma, and San Miguel counties, as well as the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, agricultural producers, fish and wildlife managers, and conservation and recreation organizations.

The resulting legislation is bi-partisan and consensus-based, establishing a new National Conservation Area and Special Management Area that will protect wildlife, cultural and historical resources, and existing uses of the land while enhancing local economies well into the future.

What states does the river cross?

Colorado, Utah

WHAT CAN YOU DO?

Please join us in thanking Senator Bennet for introducing the Dolores River National Conservation Area bill!

Stay informed with what is going on with rivers across the Southwest by following our Southwest River Protection Program.

ABOUT THE DOLORES RIVER

The River of Our Lady of Sorrows, the Dolores River, was named “El Rio de Nuestra Senora de Dolores” when a Spanish trader encountered the river in 1765. But in many ways, the only sorrowful thing about the Dolores River is that like so many rivers in the West, it is, perhaps, too well loved, resulting in chronically low flows. Recently introduced National Conservation Area legislation has brought the Dolores River back into the spotlight.

Humans have lived in the region the Dolores flows through for more than 10,000 years, and the archeology in some of the steep, sandstone canyons is unmatched. Now, humans treasure this high-desert river for its sacred value, the crops and cattle it waters, the habitat it sustains for plants and wildlife, the amazing experience of boating it, and the clean water it provides for drinking, among other things.

With headwaters at 14,000 feet and a nearly 230-mile run to its confluence with the COLORADO RIVER near Utah, the Dolores is a gateway to truly world-class scenery. Like its neighbor, the SAN MIGUEL, the headwaters of the Dolores River and West Dolores River are also in the San Juan Mountains, but both branches flow southwest before converging just above the town of Dolores. McPhee Reservoir, where Dolores River waters are held for agriculture, is located just southwest of the town. And from there, the Dolores meets a fate shared by many rivers in the West, as every drop is allocated to agricultural production. While some reservoirs help buffer fluctuations in water availability between wet and dry years, that isn’t the case for the Dolores. Despite being the second largest reservoir in Colorado, McPhee Reservoir doesn’t have the storage capacity to store enough water to satisfy both agricultural rights and flows for recreation and endangered fish.

Water released from the dam flows sharply northwest through Ponderosa and Slickrock Canyons, uniting with the San Miguel before flowing through the Paradox Valley and, ultimately, through Gateway Canyon and into the Colorado River.

When water is released, nearly 170 miles of it are floatable. In 2016, the Dolores River ran for the first time in five years. A healthy winter snowpack translated to some short-lived and well-celebrated releases that allowed for boating through the amazing Dolores River Canyon. On the rare opportunity to float, paddlers marvel at the towering sandstone walls, the regular encounters with beavers, the unique way floating the Dolores becomes paddling through coyote brush and tamarisk. Because high water flows are such a rare occurrence, campsites are overgrown and under established.

Since 1968 when initial construction on the McPhee Dam began, stakeholders in the region have worked to develop river management plans that support the river’s cold water fish species, alongside agricultural irrigation and the desire for recreation flows. The reservoir was completed in 1984, and in 1990, a dry summer limited flows from McPhee to less than 20 CFS, resulting in a major kill of cold water fish. Even lower summer flows have been recorded in recent years, killing native fish, destroying the geomorphology of the channel, shorting irrigators and the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, and stressing wildlife.

WILD AND SCENIC ELIGIBILITY

In both 1976 and again in 2013, the Dolores River was found suitable for designation under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act by the U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management, giving the Dolores River administrative protections for its free-flowing character and outstanding values. After a lengthy negotiation process, language in the Dolores River National Conservation Area bill would trade away Wild and Scenic suitability for similar protections of the river’s free-flowing character and outstanding values within the National Conservation Area (NCA) and Special Management Area (SMA). However, this would not preclude designating the Dolores River or its tributaries under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act in the future it there is social and political support for such a designation.

Congaree River

SOUTH CAROLINA’S WILDERNESS CONNECTION

It’s only 50 miles long, but the Congaree is many rivers in one. From its origin at the confluence of the Broad and Saluda rivers near the Piedmont fall line in downtown Columbia, South Carolina, to its remote, bottomland terminus at Congaree National Park, the Congaree has a rich cultural history, varied wildlife and remarkable habitat linking South Carolina’s capital city to one of its large natural landscapes.

There is much to explore along the Congaree River, making it an obvious choice for the first Blue Trail established by American Rivers and our partners in 2007. Starting near Columbia, the aquatic trail is the ideal way to experience all the river has to offer through canoeing, kayaking, fishing, and other family-friendly activities. But the undeniable highlight of the journey is Congaree National Park, the largest protected wilderness in South Carolina.

Designated as an old growth forest, an International Biosphere Reserve, a Globally Important Bird Area and a National Natural Landmark, Congaree National Park boasts 90 species of trees and the tallest Loblolly Pines alive today (169 feet). The park preserves the largest tract of old-growth bottomland hardwood forest left in the US, including enormous bald cypress trees throughout. The wilderness provides cover for bobcats, deer, wild pigs, coyotes, armadillos, turkeys, and otters while the river hosts turtles, snakes, alligators, and several types of fish.

Visitors can enjoy nature study, hiking, fishing, birding and camping. They can also paddle 20 miles of the Blue Trail within the park. The Congaree merges with the Catawba-Wateree to form the Santee River at the southeast corner of the park before flowing into Lake Marion and eventually the Atlantic. The Congaree merges with the Catawba-Wateree to form the Santee River at the southeast corner of the park before flowing into Lake Marion and eventually the Atlantic.

Did You know?

The Blue Trail program was founded on Congaree River when 50-mile river was recognized as an important connection between the city of Columbia and Congaree National Park.

Congaree National Park is South Carolina’s only National Park. In 2014, Congress voted to fund expansion of the park by 2,000 acres in order to connect the section on the Wateree River Blue Trail.

The Congaree River is home to many of the tallest trees in the Southeast, found within the federally designated wilderness area in Congaree National Park.

WHAT STATES DOES THE RIVER CROSS?

South Carolina

The Backstory

The Congaree River is heavily influenced by upstream dams, including the 200-foot-high Saluda Dam that creates 48,000-acre Lake Murray, the Columbia Diversion Dam on the Broad River just above the confluence, and the Parr Shoals Dam forming Parr Shoals Reservoir about 25 miles higher upstream.

After being blocked by the Columbia Diversion Dam and Canal for 125 years, those 25 miles of the Broad River above Columbia are now open to American shad and other migrating fish—and to the anglers who chase them—thanks to a fish passage installed in 2006. In addition to shad, blueback herring, and American eel, the rare robust redhorse sucker and other resident species now use the fishway to ascend the river and return to native spawning grounds.

The fishway was the first in the Southeast to be constructed and operated through the federal licensing renewal process. In a separate relicensing agreement for the Saluda Dam in 2009, American Rivers helped negotiate an agreement that provides more natural, seasonal flows on the Saluda River for several weeks a year that benefit the health of the river and its web of life extending to the Congaree. The agreement includes protection and restoration measures for striped bass and shortnose sturgeon as well as rare freshwater mussels and rocky shoal spider lilies. Recreational access and special water releases for fishing and whitewater paddling are also included.

The Future

The next piece of the federal relicensing trifecta is on the Broad River’s Parr Shoals Dam, where American Rivers is among a coalition currently seeking more water released downstream from Parr Shoals and its sister reservoir, Monticello. We’re also asking dam operators South Carolina Electric & Gas to install a fish ladder and improve recreational access as part of the relicensing process that occurs every 30 to 50 years.

It’s the least we can do for the Congaree River, that does so much for so many. Programs like Blue Trails, born on the Congaree, have helped thousands to connect to nature and learn important life skills, earning recognition from the Department of the Interior as a model for how communities are connecting with America’s great outdoors through their rivers.

Escalante River

The Escalante River rivals the Paria for the steep and varnished canyon it winds its way through. Cottonwoods and hanging vines wedge themselves against canyon walls. The Escalante River is remote and rugged, its flows perennial and vital in an arid landscape.

When the first Anglos, members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, entered the valley, they were struck by the bounty of wild potatoes growing there, and deemed it “potato valley”. It was more romantically named during Powell’s 1872 survey expedition in honor of Silvestre Vélez de Escalante—who led the 1776 Dominquez-Escalante Expedition.

Upper Valley and Birch Creeks collide to form the Escalante, near its namesake town in south-central Utah. Atop the Aquarius Plateau, the headwaters cut through high alpine spruce forests before descending into old-growth ponderosa, pine, and aspen. At this high end of its reach, the Escalante provides critical habitat for mule deer, upon which the resident bear and mountain lion populations rely. The river carves its way off the plateau through a canyon with walls that reach nearly 1,100 feet in places.

The ephemerality of paddleable flows demands the same of those desiring to float it. Harry Aleson and Georgie Clark were the first, on record, to manage a trying float through the river’s canyon, timing their epic journey with the unpredictable spring and summer flows fed by early season runoff and monsoons.

Rated Class II overall, the Escalante can be deceiving. Aside from the fact that it’s nowhere near any beaten bath, there are a lot of variables: debris carried on flood waters can create strainers that require portages, floods themselves are a major risk, and there are few exits. For both the Escalante and the Paria, and as is the nature of so many desert rivers, the window to run is short, unpredictable, and unparalleled in humbling and spectacular scenery, and true adventure. During low flows, the canyon-carved river and its critical tributaries offer unmatched hiking and backpacking.

Did You know?

The Escalante River was one of the last sizable rivers to be discovered in the contiguous US.

During peak runoff, the Escalante can be as much as 100 bigger than the flows it maintains the rest of the year.

The Escalante River basin provides critical habitat and resources for nearly 300 species of birds, fish, mammals, reptiles, and amphibians.

What states does the river cross?

Utah

how can I help?

Stay informed with what is going on with rivers across the Southwest by following our Southwest River Protection Program.

Tell the Trump Administration to retain and support the Waters of the United States rule under the Clean Water Act. Take action here.

It is this—the river’s spectacular beauty, the habitat it provides, the adventure it inspires—that make the Escalante so vital to the Southwest. Though the Escalante River has been identified for Wild & Scenic protections by the National Park Service and various non-profits, this rare river is threatened by mining claims, impacts of climate change, and development. Constant threats including reductions to the size of Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument further imperil the rare intactness of this fragile desert ecosystem. For decades, volunteers have spent millions of dollars and countless hours to remove nonnative species and improve the river’s habitat and condition, but proposed management changes invite devastating impacts from increased grazing, mining, and oil and gas drilling, and erosion from OHV use that would directly impact water resources.

Feather River

The Feather River flows from the northern end of Sierra Valley in southeastern Plumas County, and consists of three branches. As the Sierra Nevada’s largest and northernmost river, it flows 185 miles from its headwaters to the Sacramento River.

78 miles of the Middle Fork of the Feather River (above Oroville Reservoir) is listed as a National Wild and Scenic River, with different sections classified as wild, scenic, and recreational. The Middle Fork also has a 111-mile dam-free river reach, from the source of headwaters to Oroville Reservoir. Popular for fishing Steelhead, Chinook salmon, catfish, shad, and bass, the river offers an excellent Class I-II, 94-mile canoe trip from Oroville to the American River confluence in Sacramento.

The 3,200 square mile watershed is comprised of 65% public land, managed by the U.S. Forest Service. The watershed hosts camping and swimming opportunities, riverfront oak savanna, and riparian forests. The watershed is also home to Feather River stonecrop, an endemic plant that grows along the slopes of the river in Plumas and Butte counties.

Historically, the Middle Fork was one of 12 originally designated rivers in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System (1968). Water from the Feather River is heavily used and diverted into irrigation ditches for agricultural purposes. The river has formed several valleys, including Indian Valley and American Valley, which are used primarily for grazing, hay production, and agriculture. The site of the river’s headwaters, Sierra Valley, is the largest high-alpine meadow within the continental United States, and is an important stopover site for migratory birds.

THREATS TO THIS RIVER

American Rivers played a lead role in the relicensing of Oroville Dam, the tallest in the United States and the largest dam in the CALIFORNIA STATE WATER PROJECT. Oroville blocks salmon and steelhead from reaching many miles of spawning habitat and dramatically alters the flows and water quality of the Feather River downstream. In 2006, participants in the relicensing reached a settlement agreement that will benefit the Feather River in several ways, including improving flows and water temperatures for salmon, restoring floodplain habitat and expanding habitat for salmon and steelhead, and improving opportunities for river recreation.

As of March 2013, implementation of the settlement agreement is still pending approval of the National Marine Fisheries Assocation. American Rivers is currently working to establish a Blue Trail through Oroville, CA in conjunction with the projects planned as provisions of the settlement agreement. A Blue Trail will provide benefits and opportunities to the local community and visitors alike, and will integrate area attractions like the Oroville Wildlife Area and other settlement agreement projects and enhancements.