Green-Duwamish River

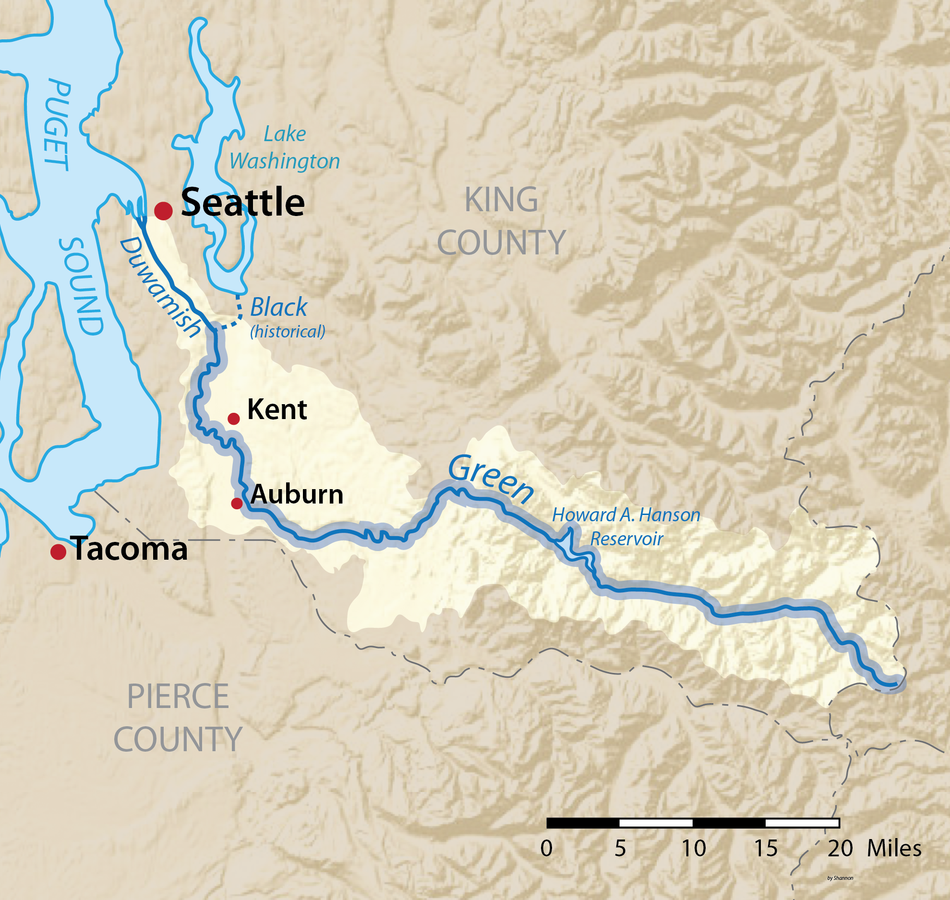

Seattle may be surrounded by water, but the Green-Duwamish is the city’s only river. The Green flows out of the Cascade Mountains just north of Mount Rainier, through Flaming Geyser State Park, and down to Elliott Bay through communities including Auburn, Kent, and Tukwila. At Tukwila the Green turns into the Duwamish River, where there was once a confluence with the since-rerouted Cedar and Black rivers.

Threats and Opportunities

The Green River Valley – where Kent and Auburn are located – is home to the second largest warehouse district on the West Coast. Below that, the Duwamish is an industrial river that feeds into the heart of the Port of Seattle.

Up higher in the system, threatened salmon and steelhead are effectively blocked from the river’s headwaters by Howard Hanson Dam, a flood control structure that lacks a passage system for outmigrating juvenile salmon. An adult fish passage system at Tacoma Water’s diversion dam just downstream is essentially useless until juvenile fish passage is constructed at Howard Hanson Dam.

American Rivers is working to integrate improvements to river habitat in the lower Green/Duwamish with fish passage in and out of the river’s headwaters.

In the lower Green River, we are focusing on ensuring that the Green River System-Wide Improvement Framework process currently underway includes a robust plan to restore and broaden significant portions of the Green’s highly developed floodplain, as well as provide for planting trees along the river to reduce water temperatures that currently can be deadly for adult salmon returning upriver to spawn.

In the upper Green, we are fighting for a juvenile fish passage system to be installed at the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Howard Hanson Dam, a flood control project that also helps store water for the City of Tacoma’s water supply. This fish passage system was supposed to be complete by the early 2000s, but it is still sitting on the drawing board without funding.

Funding floodplain restoration makes more sense with juvenile fish passage and vice versa – each project makes the other a more valuable investment.

Gila River

The Origin of Wilderness

The Gila River could be considered the birthplace of wilderness.

When Aldo Leopold convinced the US Forest Service that the headwaters of the Gila should be designated the world’s first primitive area back in 1924, it set the stage for the Wilderness Act of 1964. Deservingly, the Gila became the nation’s first congressionally designated Wilderness and remains the largest Wilderness Area in New Mexico.

The West Fork, Middle Fork, and much of the East Fork of the Gila River sit in the shadows of the Black Range along the Continental Divide and the rugged Mogollon Mountains looming at elevations upwards of 10,000 feet in the Gila Wilderness. Surrounded by a varied landscape that includes one of the world’s largest and healthiest Ponderosa Pine forests, the Gila headwaters help sustain abundant wildlife ranging from wild turkeys, eagles, and dusky grouse to deer, pronghorn, elk, bighorn sheep, javelina, cougars, and black bears. Several packs of reintroduced endangered Mexican wolves have established themselves in the Wilderness Area alongside the world’s largest population of rare Mexican spotted owls.

Renowned for its high quality bird habitat and populations of unusual species like the endangered Southwestern Willow Flycatcher, threatened Yellow-billed Cuckoo, Common Black-Hawk, Montezuma Quail, and Elf Owl, the upper Gila is a unique recreational attraction. The surrounding wilderness offers fishing for native trout, hunting, backpacking, horseback riding, and camping across hundreds of miles of trails. There’s generally a short boating season in the spring with the bonus of several natural hot springs to soak in along the river.

The Backstory

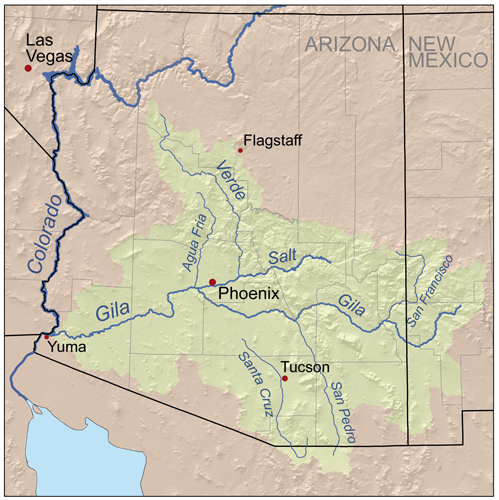

Few people realize that the Gila is one of the longest rivers in the West. That’s because it’s typically drained dry before getting halfway through its 500-mile voyage west to the Colorado River near Yuma, AZ. Once navigable by large riverboats from its mouth to Phoenix, the Gila below Phoenix today crosses the Gila River Indian Reservation as an intermittent trickle due to large irrigation diversions.

Thanks to the leadership of New Mexico Senators Martin Heinrich and Tom Udall, we have the opportunity to protect this amazing, historic watershed, permanently. In May 2020, the Senators introduced the M.H. Dutch Salmon Greater Gila Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, which would protect nearly 450 miles of the Gila and San Francisco Rivers and their tributaries under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, the premiere federal river protection legislation in the United States.

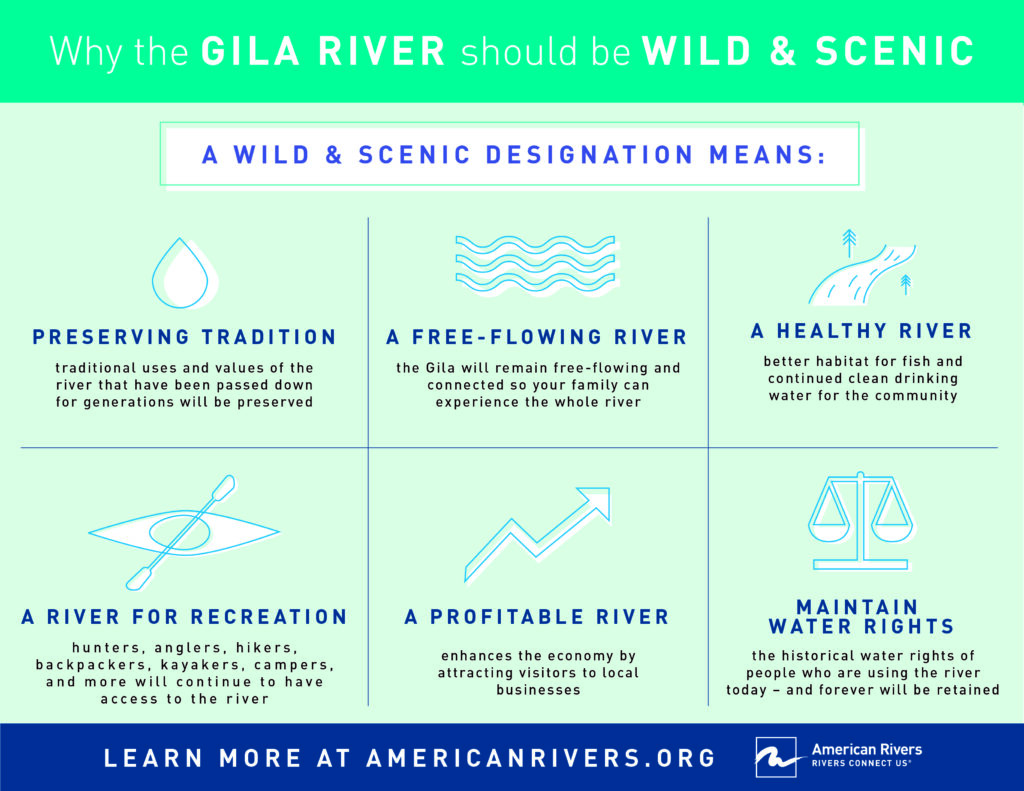

Why a Gila River Wild & Scenic designation?

Of the 108,014 miles of river in New Mexico, only 124 miles are permanently protected as Wild & Scenic.

The current Wild & Scenic proposal would protect more than 436 miles of the Gila and San Francisco Rivers, all on existing federal public lands.

The outdoor recreation industry employs about 99,000 New Mexicans and generates more than $623 million in state and local taxes annually. The Gila River is an important part of that contribution to the state’s economy.

A Wild and Scenic designation would protect access to the river for hunting, fishing, rafting, hiking, camping, and other forms of outdoor recreation, as well as existing and historic water rights.

ABOUT THE GILA RIVER

The Gila Wilderness, where the three forks of the Gila River converge, was the first federally designated Wilderness Area in the nation.

The Gila Wilderness is the largest in New Mexico, bordering Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument and the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Area, named for the former Forest Service supervisor who fostered the idea of wilderness designation.

At nearly 60,000 square miles, the Gila River watershed covers more area than the entire Green River basin and four times as big as the drainage of Idaho’s Salmon River.

Between 1848 and 1853, the Gila River briefly marked the southern boundary of the United States.

What states does the river cross?

New Mexico

In order to be considered for Wild and Scenic designation, a river must exhibit some Outstandingly Remarkable Values, and the Gila certainly qualifies with a number of these ORV’s. It is definitely scenic, it has rich historic and cultural qualities. It features varied recreational opportunities, as well as a vibrant recreational economy that benefits many people across the region. Lastly, there are abundant fish and wildlife throughout the region, including rare and endangered species like the Gila trout, the Southwest Willow Flycatcher, and the northern Mexican garter snake.

Wild and Scenic River designation neither limits the public from accessing public lands nor opens private lands to public access. Designation does not change the existing water rights or irrigation systems. Fishing and hunting regulations will stay the same while the habitat that makes New Mexico’s outdoor traditions special will be protected.

A Wild and Scenic rivers designation for the Gila River is a great way to protect one of the Southwest’s most iconic and treasured rivers, as well as the vast agricultural and recreational economies that depend on it. It protects existing, traditional uses of the river, it permanently maintains historical water rights, and it preserves the healthy, free-flowing nature of one of New Mexico’s last remaining wild rivers.

James River

America’s “Founding River”

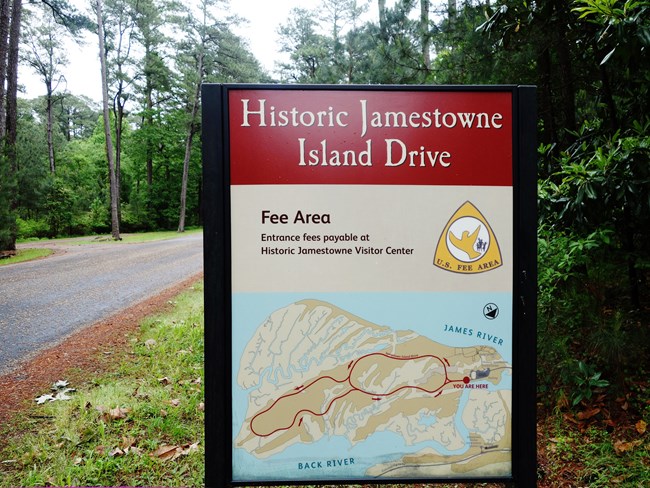

The James is known as America’s “founding river” because it was the site of the first permanent English colony at Jamestown in 1607 and home to Virginia’s first colonial capital at Williamsburg. Indigenous people lived in Virginia for 16,000 years before colonists arrived. The tribes of the Powhatan Confederacy settled in villages near the James, and the river served as a transportation corridor for Native Americans and early colonists. The James River was the site of critical battles in the Revolution and the Civil War.

Today, the James River watershed spans 39 counties and 19 cities and towns. One-third of all Virginians live in the James River watershed and rely on the river for drinking water, recreation, and commerce. The James River area attracts more than 3.5 million visitors every year. The river is part of the Captain John Smith Water Trail, designated as the first national water trail in 2006.

In 2024, Richmond was voted as the No. 1 on the America’s Best Towns to Visit list, thanks in large part to the many recreational benefits provided by the James River. Richmond has since emerged as a creative hub, with the James River playing a significant role in its cultural renaissance. The river’s proximity to the city has inspired countless artists, musicians, and entrepreneurs, making it a focal point for creative expression and innovation. The riverfront has become a vibrant area, hosting festivals, art installations, and outdoor performances, further solidifying Richmond’s reputation as a cultural and creative center in the Mid-Atlantic region.

The James is critical habitat for Atlantic sturgeon, a species that has existed for 120 million years, and is one of the largest roosting areas on the eastern seaboard for bald eagles. The river’s diverse ecosystems support a wide range of species, and ongoing conservation efforts aim to protect these habitats from the pressures of urbanization and climate change. The James River is also an essential corridor for migratory birds and other wildlife, providing critical connections between various ecosystems across the state.

American Rivers, working with our partners, seeks to protect the James River and its key tributaries to conserve the ecological, recreational, and community benefits they provide.

The National Park Service has found that the James is “one of the most significant historic, relatively undeveloped rivers in the entire northeast region.” The river’s historical and cultural significance continues to grow as Richmond’s creative community draws inspiration from its natural beauty and rich history, further emphasizing the need for its protection.

Because of these outstanding qualities, the Park Service found the James River and some of its high-value tributaries eligible for Wild and Scenic River designation as a part of its Nationwide Rivers Inventory. The agency determined that these rivers are free-flowing and have outstanding values of national or regional significance that warrant their inclusion in the National System of Wild and Scenic Rivers.

The Maury and Rivanna Rivers, two high-value tributaries of the James River, also qualify as free-flowing and have several outstandingly remarkable values, including recreation, fisheries, and scenery. Protecting these tributaries will help prevent further degradation of the James River from harmful development and other threats.

Portions of the James River and its tributaries are prime candidates for the Partnership Wild & Scenic Rivers Program, a successful model of designation that helps communities preserve and manage their own river-related resources locally by bringing together state, county, and community managers. Somewhat different from traditional Wild and Scenic River designation, the Partnership Program protects nationally significant rivers that flow through privately-owned or state-owned lands.

Transmission Lines

American Rivers has been supporting efforts challenging Dominion Energy’s transmission lines across the James River. The massive power lines and 17 transmission towers harm the integrity of this unique landscape and historic viewshed. This stretch of the James is listed in the Nationwide Rivers Inventory and has been found to have “outstandingly remarkable” historical values.

Despite strong public opposition, the Army Corps of Engineers granted a permit to Dominion Energy to construct the power lines in 2017 – but the Army Corps did not require an Environmental Impact Statement. Dominion proceeded with construction, while our partners challenged the permit in court. American Rivers filed a friend of the court brief in support of the National Parks Conservation Association, arguing the Army Corps violated the National Environmental Policy Act. The transmission lines were completed while the legal battle continued.

In February 2019, the U.S. Court of Appeals ruled that the Army Corps violated federal law and ordered the Army Corps to prepare an Environmental Impact Statement.

“The public is deeply connected to this area and the river due to its historical significance and aesthetic beauty. We need to work together to protect the Commonwealth’s priceless heritage and America’s Founding River.”-Bob Irvin, Former President of American Rivers

American Rivers has urged the Army Corps to consider energy demand, endangered species, and the Clean Water Act as well as to ignore any costs for the removal of the transmission lines and related infrastructure. Those costs were incurred after Dominion assured the District Court for the District of Columbia and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit that any construction could easily be reversed if it was found that the transmission towers and accompanying infrastructure were installed under the auspices of an unlawful permit.

“Sustainable power production and transmission are critical needs, but it’s important we look at alternatives that can serve the region’s evolving needs while preserving the character and values of the James River. The public is deeply connected to this area and the river due to its historical significance and aesthetic beauty,” said Bob Irvin, President of American Rivers

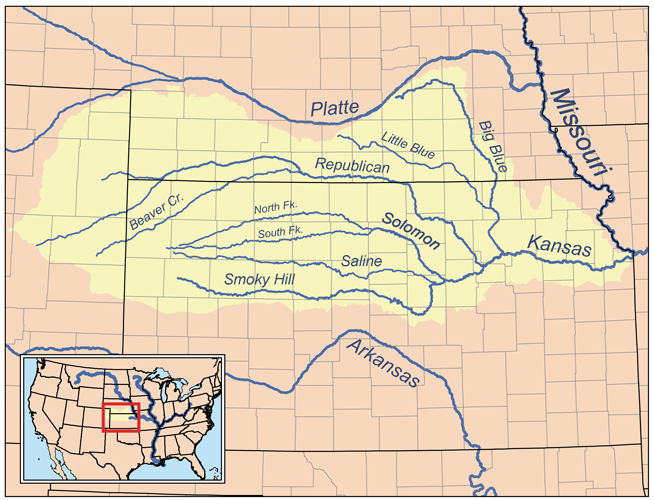

KANSAS RIVER

Midwestern Secret

It can get downright hot in The Sunflower State. Fortunately, there’s more than 170 miles of cool Kansas River flowing through the heartland to help take summer’s edge off.

The Kansas River, or “Kaw” as it’s affectionately known, is its namesake state’s most popular river for canoeing, kayaking, rowing, and fishing. Unlike many of its midwestern neighbors, the river has not been over-engineered with dams and navigation control structures, rendering it relatively free-flowing. As a result, hundreds of acres of sandbars and islands are sprinkled among meandering riverbends, providing animal habitat and opportunities for boaters to pull ashore to camp and get close to nature on what may be the top recreational treasure in the state.

As the largest tributary of the Missouri River, the Kansas is considered one of the world’s longest prairie rivers, beginning at Junction City, KS, and flowing to Kansas City. Along the way it serves as a critical drinking water supply for more than 600,000 people in addition to being used for irrigation, municipal wastewater and industrial discharges, cooling water for three coal-fired power plants, and a source of commercial sand and gravel.

But the Kaw has an undeniable fun side too. The river is dotted with more than 20 public access points and the U.S. Department of the Interior has declared the Kansas River Water Trail one of its Top 101 Conservation Projects. Canoeing and kayaking revenue is calculated at about $3.7 million per year in Kansas.

The University of Kansas rowing team uses the pool above the Bowersock Dam — the largest obstruction on the river — for training, and the Kansas City Boat Club regularly rows on the final reach of the river, near the confluence. The river and its tributaries are also home to fourteen threatened or endangered fish species.

Did You know?

The state of Kansas was named for the river. Its name (and nickname) come from the Kanza (Kaw) people who once inhabited the area.

When including the Republican River and its headwater tributaries, the length of the Kansas River system is 743 miles, making it the 21st longest river system in the U.S.

From June 26-29, 1804, the Lewis and Clark Expedition camped at Kaw Point at the river’s mouth. They praised the scenery in their accounts and noted the area would be a good location for a fort.

Because of its shallow depth, slow drainage, high silt contents, and proximity to industrial centers, the Kansas River was ranked as the 21st most polluted water body in the U.S. in 1996.

What states does the river cross?

Kansas

The Backstory

The Kansas River is no stranger to American Rivers’ Most Endangered Rivers® list, having been included five times since 1995. Some progress has been made since the most recent in 2012, although the Kaw still faces many threats. The most intense among them are impacts from in-river sand and gravel dredging used to make concrete. Dredging widens and deepens the river channel, lowering the water level of the river and the water table.

Dwindling access to water is a major threat to animals, humans, plants, and a significant agriculture industry in Kansas, especially when the looming concern of climate change is factored in. Scientific studies show that dredging a prairie river like the Kaw is particularly harmful since when sand is removed, the river attempts to fill the holes by carving away soil from the riverbanks. That erosion damages valuable farmland and wildlife habitat, to say nothing of the taxpayer-funded infrastructure like flood control structures, bridges, roads, and intake pipes for public water supplies.

The Corps of Engineers granted five-year permits for dredging operations at 10 locations along the Kansas River in 2007. But those permits to extract sand and gravel from the river stipulate that they would be terminated in any five-mile reach of the river where the average riverbed elevation dropped more than 2 feet. At least three of those permits have since been terminated, and a 2014 environmental review prompted the Corps to require a full Environmental Impact Study (EIS) before the remaining dredging permits on the Kansas River will be reauthorized.

The EIS is expected to be published in late 2016. The current permits, originally scheduled to expire Dec. 31, 2012, have been extended through the process.

The Future

The time has come to end the harmful practice of dredging in the Kaw and move on to addressing other issues. The river, for example, also drains more than 53,000 square miles of prime commercial farmland, and suffers greatly from fertilizer and animal waste pollution.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers should complete a new Environmental Impact Study on dredging, deny all new permit and tonnage requests, and end dredging on the Kansas River by 2017.

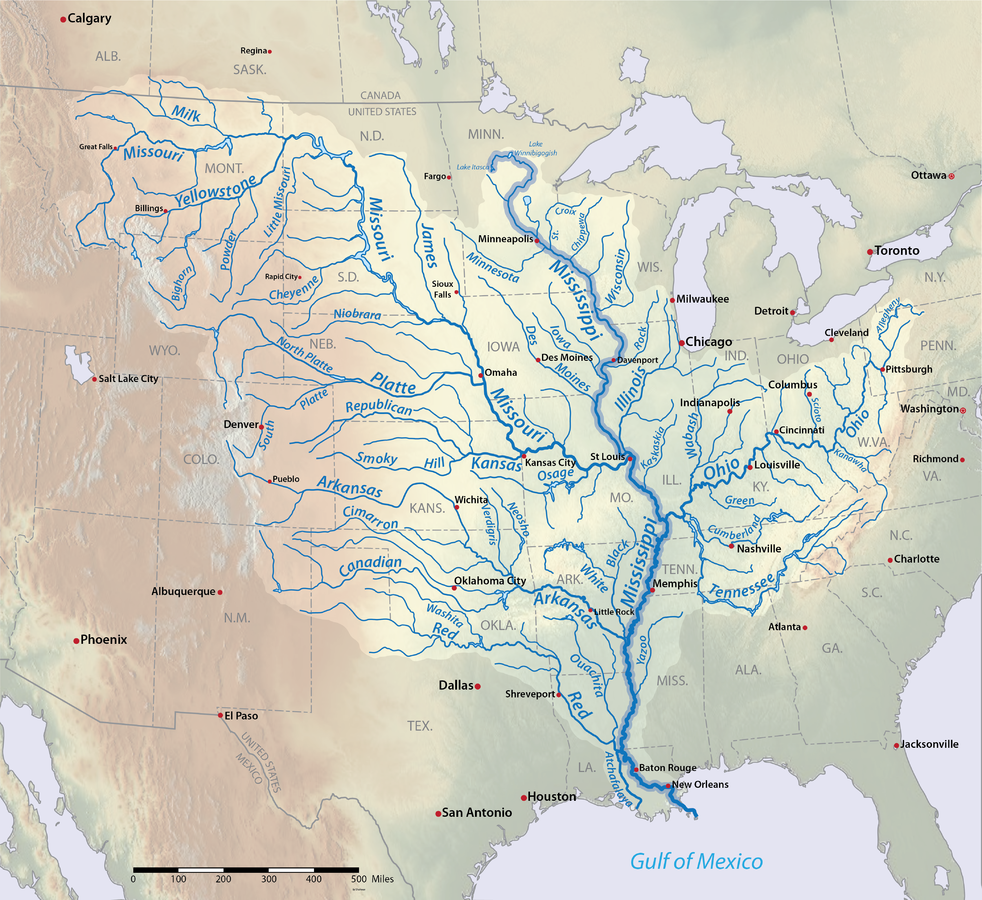

Mississippi River

A Cultural Treasure

What more can be said about the mighty Mississippi River that hasn’t been said already? Plenty, apparently.

Even the river’s resident literary laureate, Mark Twain, noted how much of the 2,320-mile Mississippi’s finest landscape has been long overlooked as our collective gaze has been fixed upon the river below St. Louis. In 1886, he told the Chicago Tribune, “Along the Upper Mississippi every hour brings something new. There are crowds of odd islands, bluffs, prairies, hills, woods and villages—everything one could desire to amuse the children. Few people ever think of going there, however… We ignore the finest part of the Mississippi.”

There is so much to consider along this great American waterway as it courses through 10 states—Minnesota, Wisconsin, Iowa, Illinois, Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Mississippi, and Louisiana—it would seem easy to overlook a few pieces. Yet, the connectivity of the river that drains 41 percent of the continental United States and carries more water than any other American river remains its most critical component.

The fabric of America truly is woven from the common thread of the Mississippi River. It’s the backdrop for countless American stories and serves as a constant muse for artists and musicians from Minneapolis through St. Louis to the Louisiana Delta. The river is a cultural treasure for the nation.

North of Davenport, IA, the Upper Mississippi River National Wildlife and Fish Refuge weaves recreation, ranging from paddling, fishing, hunting, hiking and birdwatching, into the tapestry. The upper river was once a world-renowned freshwater fishery and a full 25 percent (260 species) of all fish species in North America have been reported in the basin.

Did You know?

The Mississippi’s watershed drains all or parts of 31 U.S. states and 2 Canadian provinces between the Rocky Mountains and Appalachian Mountains.

The Mississippi ranks as the fourth-longest and ninth-largest river in the world by discharge.

The Upper Mississippi River is not the main stem of the Mississippi River. The Missouri River is far longer and larger than the Upper Mississippi. That was obvious to explorers, but the Upper Mississippi River made a convenient boundary between the United States and the French Louisiana Territory.

The sport of water skiing was invented in 1922 by Ralph Samuelson of Lake City, MN, on the river in a wide region between Minnesota and Wisconsin known as Lake Pepin.

Slovenian long-distance swimmer Martin Strel swam the length of the river, from Minnesota to Louisiana, over the course of 68 days in 2002.

What states does the river cross?

Arkansas, Illinois, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Tennessee, Wisconsin

Recreation declines as you travel south of St. Louis and the abundance of levees disconnects people from the river. Still, tourism, fishing, and recreation generate about $21.4 billion each year, and contribute 351,000 jobs along the length of the Mississippi. The river and its floodplain support more than 400 different species of wildlife, and some 40 percent of North America’s waterfowl migrate along its flyway. There are seven National Park Service sites along the corridor, including the 72-mile Mississippi National River and Recreation Area in Minnesota dedicated to protecting and interpreting the Mississippi River itself.

As the nation’s second-longest river, behind only the conjoining Missouri, the Mississippi provides drinking water for millions and supports a $12.6 billion shipping industry, with 35,300 related jobs. It’s one of the greatest water highways on earth, carrying commerce and food for the world. Half the nation’s corn and soybeans are barged on the section above the Ohio River confluence, known as the Little Mississippi.

The Backstory

Native Americans have lived along the Mississippi River since at least the 4th millennium BCE, including the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Quapaw, Osage, Caddo, Natchez, and Tunica in the Lower Mississippi, and the Sioux, Sac and Fox, Ojibwe, Pottawatomie, Illini, Menominee, and Winnebago in the Upper Mississippi. The river provided transportation, clean water, and abundant food, including freshwater mussels and fish.

The richness of resources proved equally tempting to European settlers who first learned of the Mississippi from Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto in 1541, followed by French explorers Louis Jolliet and Jacques Marquette who traveled south down the river in the 17th century. Soon after, the race between countries to settle the river’s shores led to conflict and eventual development. Britain, Spain, and France all laid claim to land bordering the Mississippi River until the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. Following the United States victory over Britain in the War of 1812, the highly coveted Mississippi River officially and permanently belonged to the Americans.

The river was essential to the nation’s growth throughout the industrial revolution and beyond, altered and harnessed over time to advance navigation and reduce flood damages. Following the monumental flood of 1927, an era of federally funded levees, dredging, and diking ensued. In man’s attempt to control the river, we have leveed more than 2,000 miles of the Mississippi watershed, isolating it from its floodplain.

As a result, the mosaic of backwaters, wetlands and sloughs that once spread out seasonally across floodplain ecosystems were drained and cut off from the river, degrading habitat and threatening the vast array of fish and wildlife that traditionally call the Mississippi River home. The basin provides critical habitat for more than 300 candidate species of rare, threatened or endangered plants and animals listed by state or federal agencies.

A 2010 St. Louis Dispatch editorial had this to say:

“For thousands of years, the Mississippi River provided fertile habitat for millions of birds and fishes along its 3,000 miles. Then came the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, damming and channeling the big river until it assumed its form today: A giant barge canal, mostly devoid of animal life.”

These days, the Mississippi is more an over-engineered canal prone to catastrophic flood than the dynamic natural system it once was. While some areas are reconnecting the floodplain to the river, it still struggles to regain natural floodplain functions, and in many areas levees are seen as the only tool to manage flood risk. In addition to the lingering habitat-degradation problems, the river now contends with invasive species issues and excessive nutrient pollution from agriculture that isn’t regulated under the Clean Water Act.

The Future

American Rivers dedicates the majority of our Mississippi work to restoring the Upper Mississippi River, where the resurrection story is just beginning to unfold. We’re focused on opportunities to help reconnect the Mississippi River to itself through dam removal in Minneapolis and levee modifications that will help restore lost habitat and river function.

In both 2014 and 2015, we helped secure full funding of $31 million for the Upper Mississippi River Restoration Program and in 2015 Congress closed the Upper St. Anthony Falls Lock. Closure of the navigation lock could open the door to restoration of an 8-mile stretch of historic big river rapids through downtown Minneapolis.

Long-term restoration goals begin with increasing buyouts of properties in the floodplain, followed by levee setbacks that enable the river to occupy more of that floodplain. That allows silt to deposit in a more natural way and lets wetlands absorb polluted runoff.

We’re actively working against proposals by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to build unnecessary and costly new locks at several dams on the Upper Mississippi River system that would expand a process recognized as a primary driver of habitat degradation along the river. Several efforts to build new or raise existing levees along the Upper Mississippi also remain. One battle dates back to the 1950s over a proposed levee in New Madrid, MO, that would cut off the region’s last remaining piece of floodplain connected to the Mississippi River and drain an area of wetlands the size of Washington, DC.

Meanwhile, we’re working to draw attention to the Upper Mississippi restoration program that is routinely underfunded even as experts estimate costs of about $1 billion annually to fully restore historic river habitat. It’s a lot of money, and a lot of work.

But let’s face it: There’s only one Mississippi River, and it still has plenty of story left to tell.

Maumee River

Ripe for Rediscovery

The Maumee River is on the brink of a recreational renaissance Sure, the massive river draining into Lake Erie just outside of Toledo, Ohio, has been on the map for centuries, serving agriculture, industry and early Native Americans. But lately this hard-working river has been showing its leisurely side.

With the largest watershed of any Great Lakes river (8,316 square miles), the Maumee officially begins at the confluence of the St. Joseph and St. Mary’s rivers in Fort Wayne, Indiana, draining all or part of 17 Ohio counties, two counties in Michigan, and five more in Indiana. That’s a lot of river to roam.

The fish—and fishermen—have long made use of all that water, especially in spring, when one of the largest migrations of riverbound walleyes east of the Mississippi makes its way up the Maumee from Lake Erie, the Detroit River and Lake St. Clair in Michigan. The annual event attracts anglers by the thousands. Upstream, the scenic rural setting doubles as a birder’s paradise.

And now cities like Toledo are looking to bolster that recreation economy by building new parks along the Maumee that improve community access and help foster a connection to the river. The recently unveiled Maumee River Water Trail proposed between Antwerp, Ohio, and Maumee Bay in Toledo includes access points spaced about every 10 miles for floating, fishing and a growing number of stand-up paddlers.

The Backstory

A lot of development has occurred around the Maumee through the years, beginning with draining the entire Great Black Swamp in order to farm the basin south of the river near Toledo. An extensive ditch system helps remove more than 70 percent of the watershed for agricultural use, eventually making its way back into the river carrying a heavy load of nutrients from phosphorus-rich fertilizer spread across some 3.2 million acres of surrounding farmland.

Did You know?

At 8,316 square miles, the Maumee is the largest river basin in all the Great Lakes.

The Maumee has been known to experience a tide-like phenomenon known as a “seiche,” which is a standing wave oscillating in a body of water. More info »

The river was also known as the “Miami” in United States treaties with Native Americans.

What states does the river cross?

Indiana, Michigan, Ohio

Combined with stormwater runoff and sewage that overloads outdated infrastructure, the nutrients have triggered enormous algae blooms over drinking water supplies in Lake Erie in recent years. In August 2014, the City of Toledo issued a “do not drink” advisory, warning nearly half a million residents not to use their tap water for more than two days due to elevated levels of microcystin in their treated drinking water. In 2013, toxins in the tap water led to a drinking water advisory in Carroll Township, just east of Toledo.

The algae bloom was the largest yet in 2015. And although it has not yet impacted fishing in the river, it has begun to take a toll on Lake Erie’s $12.9 billion recreation and tourism economy in Ohio. The lake’s reputation for fishing suffers from the unsightly, foul-smelling algae, and charter boats are forced to move farther offshore in summer months.

The Future

With more intense and frequent rainfall events predicted due to climate change in the Great Lakes basin, the likelihood of future blooms is inevitable and can only be prevented through a comprehensive cleanup strategy that reduces the amount of phosphorous in the basin and improves stormwater management.

Positive steps include an increase in the amount of green stormwater infrastructure like rain barrels, rain gardens and green roofs throughout the basin. Pervious pavement is being used in the right scenarios and cities are incorporating more bio-retention areas along roadways.

The hands-on effort to connect the community to the Maumee River through recreation may be the most important educational tool of all. Fortunately, the wheels are already in motion, although there’s still much to be done.

Marsh Creek

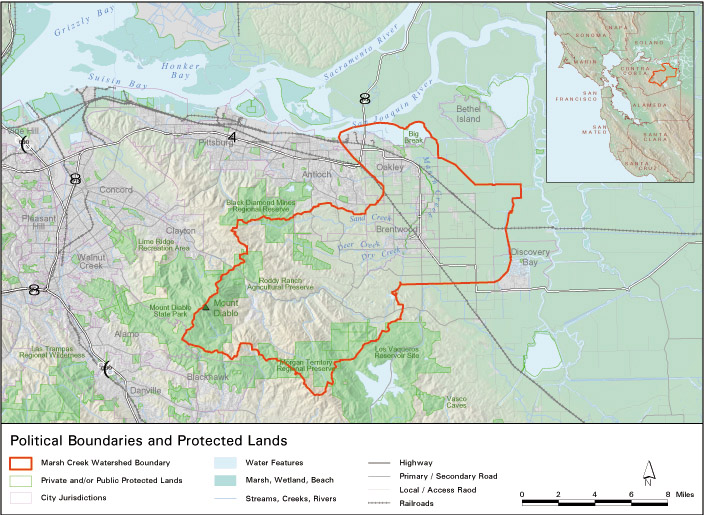

Located in Contra Costa County, the Marsh Creek watershed is quickly urbanizing due to the rapid growth of several communities.

The headwaters of Marsh Creek is located on the eastern side of Mount Diablo, and the creek then runs 30 miles through the communities of Oakley, Brentwood, and Antioch before reaching its mouth at the western side of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, northeast of Oakley.

The Marsh Creek Reservoir, created in the 1960s by damming a section of the creek, helps regulate the flow and provide flood protection of Marsh Creek through developed areas. The lower portion of Marsh Creek (below Marsh Creek Reservoir) was channelized in the 1950s and 1960s to help control flooding in this agricultural area. However, agricultural lands are fast giving way to urban and suburban development. Constrained, unvegetated floodplains lack the capacity to slow floodwaters, filter incoming sediment and other pollutants, or to create a cool and shady habitat for fish and wildlife. As the landscape transforms, American Rivers is working with local groups and agencies to help integrate a healthy and functional river into the human landscape.

Due to its unique connection between the Diablo Range and the Sacramento-San Joaquin Basin, Marsh Creek is considered a priority watershed for habitat restoration for spawning salmon. American Rivers has been leading a partnerships to restore Marsh Creek starting in 2010 with a fish ladder that now enables Chinook salmon to pass a 6-foot high dam and access 7 miles of upstream spawning habitat.

Marsh Creek is the first tributary encountered by salmon returning from the ocean through the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, thus Salmon spawned in Marsh Creek will enter the Delta in a prime location: adjacent to Dutch Slough, one of the largest habitat restoration projects in the Delta and downstream from most Delta diversions and other mortality sources.

American Rivers is now engaged with the City of Brentwood, East Bay Regional Parks, Friends of Marsh Creek Watershed (FOMCW) and especially, with the Contra Costa Flood Control District to restore floodplain habitat to the straightened and narrowed Marsh Creek channel that runs through the rapidly urbanizing corridor. Where tributaries Deer and Sand Creeks join Marsh Creek, our team is restoring nearly a mile of riparian corridor in the heart of Brentwood at the “3-CREEKS PROJECT”. Land moving to widen the creek corridor and improve the Marsh Creek Regional Trail, a pedestrian path along Marsh Creek, is complete as of mid-December 2020. Restoration planting of native tree, shrub and forb species will begin early in 2021. We are happy and proud to be helping lead this transformation of a somewhat beleaguered flood control channel back to a healthy and vibrant living creek that will support local kids and grownups, salmon, birds, wildlife, and native plants.

The East Bay Regional Park District Manages the 6.5-mile Marsh Creek Regional Trail, which provides community members with hiking and biking opportunities along Marsh Creek. The trail will eventually be 14 miles long and will connect the Delta with Morgan Territory Regional Preserve and Round Valley Regional Park.

Lower Basin of the Colorado River

The Colorado River provides drinking water for one in ten Americans, nourishes cities including Las Vegas, Los Angeles, Denver, and Phoenix, and the lower half of the river waters nearly 90 percent of the nation’s winter vegetables. However, water demands are outstripping supply, and climate change makes the situation even more urgent. The river is at a breaking point, with looming shortages in supply that could threaten the security of water and food production and a significant portion of the national economy. The Trump Administration, Lower Basin state water leaders and the Congressional delegations of Arizona, Nevada and California must prioritize collaborative water management solutions to ensure the Lower Colorado can continue to sustain the Southwest and the nation as a whole.

Transitioning from Upper Basin to Lower Basin at Lee’s Ferry below Lake Powell in northern Arizona, the Lower Colorado river winds through Nevada, Arizona, California, and into Mexico, but with so much water withdrawn along the way for agricultural, industrial, and municipal uses, it dries up before reaching its natural delta in the Gulf of California. The river provides drinking water to 30 million people in some of the largest and fastest-growing metropolitan areas in the U.S., including Las Vegas, Phoenix, Tucson, Los Angeles, and San Diego.

The river is critical to the future of agriculture in the region, providing water for over five million acres of farmland growing crops worth roughly $600 million annually. The Lower Colorado supports thriving recreation and tourism, carving the Grand Canyon and supplying water to the fountains along the Vegas Strip. All told, the Lower Colorado has an annual economic impact of $900 billion. The river also provides essential habitat for six threatened and endangered species and is a treasured recreational and spiritual resource in the region. Additionally, a number of Native American tribes, both along the river and across Arizona and Southern California, hold a deep cultural and spiritual connection to the river. Their voice in the future of the Southwest is important, and critical to how the river is both respected and managed in coming decades.

The Threat

In short, with all that’s asked of it, the Colorado River is overused. More water is taken out each year than goes in, leading to a supply deficit that threatens the long-term stability of the cities, farms, and tribes in the region. Each year, the Lower Basin uses an average of 1.2 million more acre-feet of water (an acre-foot is about 325,000 gallons or about one football field of water, one foot deep) than it receives in flows from the Upper Colorado River Basin. This is roughly equivalent to the water use of two and a half million households in the Southwest. Historically, Lower Colorado Basin water users have overcome this supply imbalance by drawing from storage (the combination of Lake Mead and Lake Powell) that accumulated over decades when water demand was lower. This is not a sustainable solution in the face of climate change, drought, and rapid population growth, which are now consistently straining the river’s water supply.

Over the past several years, federal agencies and state, local, and tribal water leaders have made considerable progress toward water conservation and programs that reduce overuse of the river. In order to protect this crucial water supply for the long term, water agencies and leaders in all 3 Lower Basin states have been cooperating to reduce water withdrawals and shore up critical water levels in Lake Mead. They have been operating under terms laid out in a 2007 agreement, and negotiating new terms to allocate the risk of water shortages. These new terms, known as the Drought Contingency Plan, have been hammered out in concept but final agreement has so far been stymied by local political disagreements, particularly within Arizona. Overcoming these challenges will require Arizona water agencies, users, and elected leaders to emphasize collaboration over competition, and make hard compromises to ensure the stability of water supply for the state’s residents and economy.

Additionally, progress on the river is threatened by the Trump Administration’s Fiscal Year 2018 Budget proposal, the implementation of which would cut funding to critical federal programs like the Bureau of Reclamations’ System Conservation Program, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Regional Conservation Partnership Program, and the Department of Interior’s WaterSMART program and Title XVI grants for municipal conservation and efficiency efforts. These cuts could potentially reverse progress made by states, cities and farmers to reduce water consumption in the Lower Colorado River Basin.

Failing to address the overdraft in the immediate future will result in severe economic and ecological impacts to the Lower Colorado River. Water levels will continue to drop, triggering an official “shortage declaration” by the Bureau of Reclamation and forcing mandatory water delivery curtailments. While heavy snowpack in the Rocky Mountains may temporarily reduce the risk of shortage, as recently as August 2016, the Bureau projected a greater than 50 percent chance of shortage in 2018. Cities and farms would almost certainly face new water use restrictions. Arizona water users would be the hardest hit — even though California farms and cities are further downstream, federal law gives Arizona lower priority access to Colorado River water.

What Must Be Done

The Colorado River, from its headwaters in the Colorado and Wyoming Rockies, through the Grand Canyon and on to the once-massive estuary in the Gulf of California, is the tangled thread that ties the entire Intermountain West together. Our economy, our recreation, our food, and our culture and spirituality are all connected by the waters that flow through the veins and arteries of this system. We are inherently connected to it, and the river forms both a cultural connection as well as a life-sustaining support system for a broad cross-section of our nation. It deserves our respect, our care, and our diligence.

Water users in Arizona are engaged in negotiations about how they will adjust to the reduced supply of water under DCP conditions. Governor Ducey, the Arizona Department of Water Resources, and the Central Arizona Project have been instrumental leaders in creating partnerships to develop and support an Arizona DCP plan which will reduce demand on the river and create a more flexible water supply system. Ultimately, these water leaders, the state’s cities and Tribes, and the Arizona legislature hold the keys to a successful DCP, and to the long-term security of the state’s water supply. American Rivers, its members and partners, are working collaboratively with these decision makers to identify key actions, and ensure support for sound water management.

Little Tennessee River

Living Large

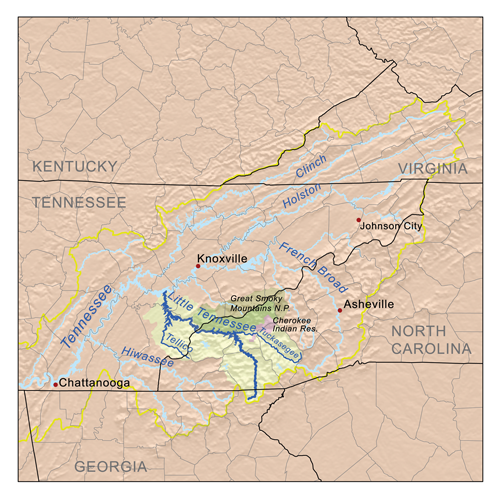

You’d be hard pressed to pick just one exceptional aspect of the Little Tennessee River. From its headwaters in the Chattahoochee National Forest of northeast Georgia, through the mountains of scenic western North Carolina, along the southern border of Great Smoky Mountains National Park, on down to Fontana Lake and its eventual confluence with the Tennessee River near Knoxville, the “Little T” is 135 miles of Appalachian Mountain glory.

Nestled amid some of the oldest mountains on Earth, the basin harbors an incredibly rich ecosystem. More than 3,000 species of plants provide habitat for a wide variety of mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish, and mussels. More than half the rural basin is publicly owned and nearly 90 percent is forested, a portion of it in the Cataloochee Valley that serves as the site for successful reintroduction of elk eradicated from the region more than a century ago.

Legendary trout streams and family-friendly whitewater (Class I-III), plus miles of mountain biking, horseback, and backpacking trails—including the Appalachian Trail—make the free-flowing upper basin a vital driver of western North Carolina’s vibrant recreation-based tourism economy. The watershed drains portions of three national forests and the bounty of waterfalls in Panthertown Valley, southwest of Asheville, NC, serve as incentive to explore further. Fortunately, Smoky Mountain Blueways has 51 public access points mapped out on the upper watershed alone, including the Cheoah, Nantahala, Oconoluftee, Tuckasegee, and the Little Tennessee itself.

But the basin’s most impressive feature is its ability to nurture a vast array of aquatic life. The Little Tennessee is designated as a Native Fish Conservation Area, containing more than 100 species of native fish, 10 species of native mussels, and a dozen crayfish species. It’s home to 35 fish, mussel, or crayfish species considered rare at the state or federal level, including fish like the Citico darter and Smoky madtom and Little Tennessee crayfish, which isn’t found anyhere else in the world. The 24-mile reach of the the river from Franklin to Fontana Reservoir is believed to contain all aquatic wildlife present prior to colonialization’s effects.

Water quality is excellent throughout the majority of the basin, and the Little T provides clean drinking water to surrounding municipalities, including Franklin, Sylva and Cherokee, a reservation that is home to the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, numbering more than 13,000, and stewarding the area’s rich natural resources.

Did You know?

The 24-mile reach of the Little Tennessee River between the town of Franklin and Fontana Reservoir is believed to contain all of the same aquatic wildlife that was present when British colonists arrived in North America.

As a Native Fish Conservation Area, the Little Tennessee River is home to more than 100 species of native fish, 10 species of native mussels, and a dozen crayfish species, including 32 species considered rare at the state or federal level.

Panthertown Valley, where the Tuckasegee River originates in North Carolina, is often referred to as the “Yosemite of the East” because of its granite rock formations. It’s home to dozens of waterfalls and miles of hiking and biking trails.

The Nantahala River, another tributary of the Little Tennessee, is a very popular whitewater paddling destination, and was home to the IFC World Freestyle Kayaking Championships in 2013.

What states does the river cross?

Georgia, North Carolina, Tennessee

The Backstory

At 480 feet, the concrete dam forming Fontana Lake is the highest in the eastern U.S. and impoundments throughout the lower basin remain an ongoing issue. Much of the native fish biodiversity remaining around dams on the Little Tennessee and its tributaries survives in isolated fragments of relatively intact native habitats.

However, a pair of recent dam removals on tributaries has helped restore natural flows, enhanced recreational opportunities, and increased aquatic habitat for endangered species. The Dillsboro Dam removal in 2012 saw the return of endangered Appalachian elktoe mussels and the Citico Dam removal gave new life to three endangered fish, including the exceedingly rare Citico darter.

The more pressing threat is seen in habitat degradation due to urban sprawl and swift, uncontrolled development in the basin. With little zoning regulation, development historically has occurred on the flatter ground in the floodplain along the riverside. The loss of riparian habitat due to development has led to increased sedimentation and diminishing water quality through polluted runoff within the Little Tennessee River Basin. As rapid population growth and urbanization continue to push into the watershed, pressure placed on the region’s intrinsic ecological and recreational values is increasing at a pace unanticipated 10-20 years ago.

The Future

Community leaders within the basin have recognized the impacts of development and zoning is coming around to address land use in rapid growth areas. Recognizing the importance of the resource to the region’s outdoor-tourism economy, officials in Jackson County, NC, have even drafted legislation aiming to designate their community the “trout capital” of North Carolina, where mountain trout fishing has an annual economic impact of $174 million.

American Rivers is prioritizing efforts on the Tuckasegee River, a significant tributary in the upper basin, focusing on restoration, recreation, and conservation opportunities surrounding the popular trout fishery. In order to further connect the community to the river and increase critical land conservation, American Rivers is proud to share the newest Blue Trail in North Carolina.

Little Plover

The Little Plover River flows six miles from clear, cold headwater springs before joining the Wisconsin River. However, dramatic increases in groundwater withdrawals have reduced river flows. Once prized for native brook trout and popular with anglers, the river’s flow has decreased to levels that threaten the persistence of fish populations. In the past decade, portions of the Little Plover River were repeatedly sucked dry, making the river the unfortunate poster child for Wisconsin’s inadequate groundwater management. The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources must adequately manage High Capacity Water Wells to safeguard the Little Plover and other rivers and lakes across the state.

Threats to This River

The Little Plover River was under great stress and its story has become a sad cautionary tale. Since shallow groundwater sources often provide water to rivers, High Capacity Wells (with a pump capacity of 100,000 or more gallons per day) can have as much or more impact on river flow than surface pipes directly drawing water from the river. Taking water from all directions can cause rivers to run dry if enough water is withdrawn. Models based on 60 years of data show reductions in flow in the Little Plover River beginning in the mid-1970’s, with more than half the historic flow missing by 2006. This reduction mirrors the more than doubling of the number of irrigation wells, which now account for about 85% of water withdrawals in the Little Plover Basin since 1980; it is compounded by municipal and industrial wells pulling from the same source.

The Little Plover River, along with several lakes in the Central Sands region, has been the most visible victim of poor groundwater management, but the problem is statewide. Wisconsin is a water-rich state, but groundwater, the water source for 70% of the population and over 90% of water used for farming and industry, is limited. Wisconsin law leaves streams, lakes, and wetlands unprotected from excessive groundwater pumping, and does not require consideration of the impacts of High Capacity Wells and their cumulative effects on groundwater supply or groundwater-dependent surface waters except in limited circumstances. Nearly all water resources are left high and dry by current law, and there is no mechanism to restore water to clearly impacted resources such as the Little Plover River.

What states does the river cross?

Wisconsin

Recently, in a positive turn of events, an administrative law judge recently issued a decision finding that the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR) must consider the cumulative impacts of groundwater pumping when considering new high-capacity well permits.

The ruling came in a case brought by Friends of the Central Sands (FOCS) and others challenging a well permit for the proposed Richfield Dairy concentrated animal feeding operation (CAFO) in Adams County. The DNR had said it lacked authority to take the impacts of existing and future wells into account when issuing new high-capacity well permits.

The judge found that the DNR, “took an unreasonably limited view of its authority,” and that the public trust doctrine, statutes, and decades of court precedent required DNR to consider cumulative impacts.

The judge’s decision reduced the allowable amount of water the dairy may pump in one year. In a companion case, the administrative law judge determined the DNR should have established a cap on the number of animals that may be confined at the CAFO.

Kootenai River

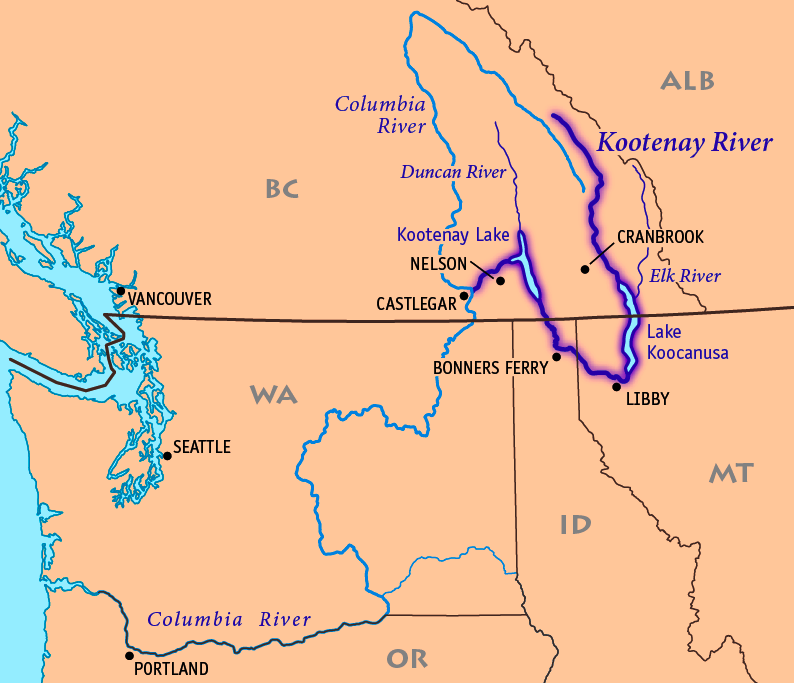

One of our country’s wildest rivers, the Kootenai River provides critical habitat for several rare and threatened native fish species, as well as wildlife like grizzly bear and woodland caribou. However, the river is threatened by runoff and waste from current mining and proposed expansions of five open-pit coal mines along the Elk River in British Columbia, a tributary to the Kootenai.

The U.S. State Department must involve the International Joint Commission in order to halt the mine expansions until an independent study of the impact of current and future mines on water quality, fish, and wildlife is completed.

Threats to This River

Large scale open-pit coal mining is currently degrading water quality and impacting fisheries and other aquatic life in the Elk River in British Columbia, which flows into the headwaters of the Kootenai River. Teck Coal operates five open-pit coal mines in the Elk River Valley. Multiple new mines that are being proposed, along with expansions at existing mining operations, are posing unprecedented risks to the clean water, fish and wildlife, and recreation values of the Kootenai River system.

Selenium, a naturally-occurring element, is released as a result of the mining, and becomes toxic at very low levels in the aquatic environment. Despite documented violation of provincial and federal water quality guidelines for selenium, four of the five mines are expanding. Each mine expansion is being considered individually, with no legal requirement to evaluate the cumulative water quality and aquatic life impacts from all five mines.

In addition to the expansions, one new mine has also been proposed and three large scale exploration projects are currently underway that could lead to even more mine proposals.

Teck Coal’s own data show that they have exceeded British Columbia’s selenium standard since 2006, with levels steadily increasing and detectable in Montana and Idaho. Selenium is a pollutant that bioaccumulates in the environment. That means its impact multiplies as it moves through the food chain. Elevated levels of selenium have already been detected in Kootenai River fish. Due to selenium contamination, the State of Montana has listed Lake Koocanusa (a dammed section of the Kootenai River on the U.S./Canadian border) as an impaired water body under Section 303(d) of the U.S. Clean Water Act.

British Columbia is expected to issue permits for expansions of two of the five open-pit coal mines in the near future. Both of Montana’s Senators have requested that the U.S. State Department investigate the existing and potential downstream impacts from the open-pit coal mines. In addition, a coalition of tribes has requested that the governments of the U.S. and Canada refer this matter to the International Joint Commission (IJC). International scrutiny of the proposed mines expansion, through the objective auspices of IJC, is the best way to ensure protection of water quality and native fisheries in the Kootenai River system.

Specifically, the U.S. State Department should direct the IJC to investigate and report on the current discharges from the five open-pit coal mines, and the current cumulative adverse impacts on water quality, fisheries, wildlife, and the environment. Given the B.C. government’s accelerated timeline for approving the mine expansions, the U.S. State Department should also request an immediate moratorium on current mine expansions based on a lack of analysis of the cumulative and downstream impacts to water quality and fish habitat.

Klamath River

Klamath River Named as 2024 River of the Year

American Rivers announced that Oregon and California’s Klamath River is the 2024 River of the Year, celebrating the biggest dam removal and river restoration in history. The River of the Year honor recognizes significant progress and achievement in improving a river’s health.

“On the Klamath, the dams are falling, the water is flowing, and the river is healing,” said Tom Kiernan, President and CEO of American Rivers. “The Klamath is proof that at a time when our politics are polarized and the reality of climate change is daunting, we can overcome seemingly insurmountable challenges and make incredible progress by working together. This is why American Rivers is naming the Klamath the River of the Year for 2024.”

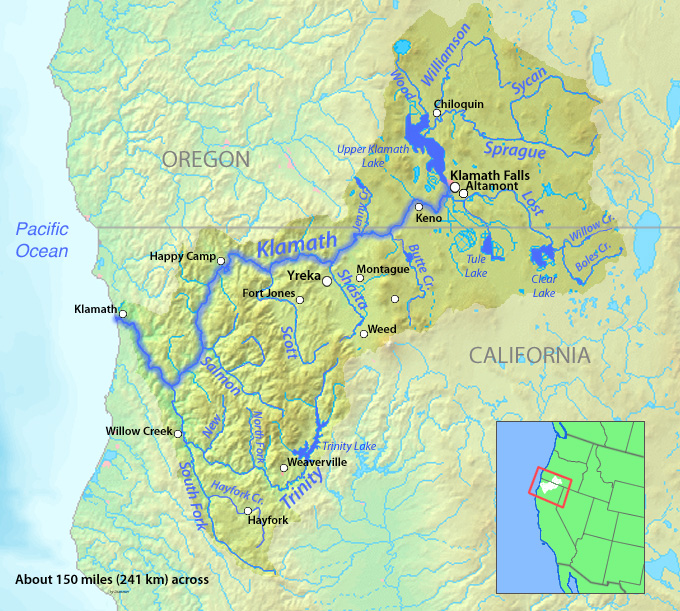

The Klamath River flows from a broad patchwork of lakes and marshes at the foot of the Cascade Mountains on the California-Oregon border and winds southwest into California. After passing through five hydropower dams, the river reaches the Pacific Ocean south of the fishing community of Crescent City.

The river has been home to indigenous people for thousands of years and tribes including the Yurok, Karuk, Hoopa, Shasta, and Klamath rely on, and care for, the river today.

Klamath River salmon runs were once the third-largest in the nation, but have fallen to just eight percent of their historic numbers. Chinook and coho salmon, steelhead and coastal cutthroat trout, green and white sturgeon, and Pacific lamprey all rely on the Klamath.

More than 75 percent of birds migrating on the Pacific Flyway feed or rest in the upper basin and the largest population of bald eagles in the lower 48 states winters in several national wildlife refuges there.

The Upper Basin

The upper Klamath basin has been called the “Everglades of the West.” However, almost 80 percent of the upper basin’s wetlands have been converted to grow thirsty crops such as potatoes, alfalfa, and hay, including nearly 23,000 acres on the Tule Lake and Lower Klamath National Wildlife Refuges. Irrigation withdrawals and polluted farm runoff have harmed the river and its fisheries.

Thanks to the efforts of our partners, MANY PROJECTS have been completed or are currently underway that are designed to improve water quality and fish habitat while making it easier for landowners to meet water quality goals that both satisfy regulators and ensure healthy water supplies for people and wildlife.

Did You know?

The Southern Oregon/Northern California Coast coho is federally listed as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act.

Low water flows in September 2002, led to the death of an estimated 34,000-70,000 chinook, coho, and steelhead on the Klamath, making it the largest salmon kill in the history of the American West.

With 286 miles classified as wild, scenic, or recreational, the Klamath is the longest Wild and Scenic River in California. Another 11 miles of the upper Klamath are designated in Oregon.

The Klamath River watershed is as big as Massachusetts and Connecticut combined.

What states does the river cross?

California, Oregon

Guardians of the River

In this film by American Rivers and Swiftwater Films, Indigenous leaders share why removing four dams to restore a healthy Klamath River is critical for clean water, food sovereignty, and justice.

Watch: ‘Voices of the Klamath’ shorts

Klamath River Dams

The original Klamath River agreements were crafted through the leadership of Tribes in the basin who came together with American Rivers and other conservation organizations, PacifiCorp, state and federal agencies, commercial fishing representatives, and members of the agricultural community to remove the dams, restore habitat and resolve decades-long water management disputes.

Dam removal will restore access to more than 300 miles of habitat for salmon. It will also improve water quality – currently, toxic algae in the reservoirs behind the dams threaten the health of people as well as fish.

Why is removing a dam important for a river’s healing? Dr. Ann Willis, California Regional Director at American Rivers, answers this question in front of one of 4 dams that will be removed as part of the largest dam removal project in history underway now on the Klamath River.

How does dam removal support communities? Dr. Ann Willis joins us from Iron Gate Dam on the Klamath River to reflect on the benefits of dam removal for salmon, clean water, Tribal Nations, and climate resilience.

But perhaps more important than the size of the dams is the amount of collaboration and the decades of hard work that have made this project possible. American Rivers has been fighting to remove the dams since 2000. Thanks to the combined efforts of the Karuk and Yurok tribes, irrigators, commercial fishing interests, conservationists, and many others, our goal of a healthy, free-flowing river is now within reach.

The Klamath River Renewal Corporation is managing the dam removal project.