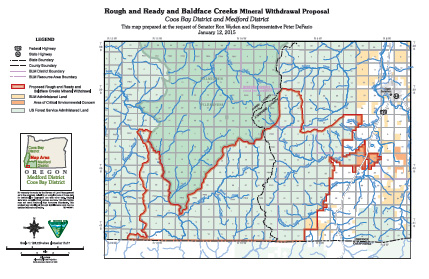

Rough & Ready and Baldface Creeks

Rough & Ready and Baldface Creeks, tributaries of the Wild and Scenic Illinois and North Fork Smith rivers, flow clean and clear through some of the wildest country in the West.

These eligible Wild and Scenic Rivers are celebrated by wildflower enthusiasts and hikers. Unfortunately, nickel mines threaten to destroy these unique, wild streams. Members of the Oregon Congressional delegation previously asked the Obama Administration to withdraw the area from mining, but the Administration did not act.

Congress and the Interior and Agriculture Secretaries must now permanently protect the natural treasures of Rough & Ready and Baldface Creeks from mining before their clean water, fish and wildlife, and wild character are irreparably harmed.

Threat to This River

At Rough & Ready Creek, a recently formed mining company has located new claims and submitted a new mining plan to USFS. It includes mining lands recommended as Wilderness, miles of road construction in the Rough & Ready Creek Botanical Area and South Kalmiopsis Roadless Area, and a smelter facility on the Rough & Ready Creek Area of Critical Environmental Concern.

At Baldface Creek, a foreign-owned mining company has submitted a plan to conduct exploratory drilling at 59 sites in the Baldface Creek/North Fork Smith watershed, across approximately 2,000 acres of the South Kalmiopsis Roadless Area. The information gathered will be used to advance mine development. Baldface Creek’s watershed was recommended as Wilderness by the Bush Administration.

The Environmental Protection Agency identified metal mining as the largest toxic polluter in the U.S. Strip mining, road construction, and metal processing would devastate this fragile, precious wild area. If one mine starts operating, thousands of acres of other nickel claims could be developed on nearby federal public lands— impacting designated and eligible Wild and Scenic Rivers and turning one of North America’s most important rare plant centers and clean water supplies into an industrial wasteland. The Forest Service already concluded that this type of mining would have drastic and irreversible impacts at Rough & Ready Creek. Dangers include high chromium content smelter waste, naturally occurring asbestos, air and water pollution, and impacts to a world-class salmon and steelhead river.

Members of Oregon’s Congressional delegation have repeatedly asked the Obama Administration to help them protect these Oregon treasures by withdrawing the federal lands in the Rough & Ready and Baldface Creek area from the 1872 Mining Law. Despite the extremely high scientific, social, and ecological values at risk, the area remains open to destructive mining and acquisition by mining companies under this unjust antiquated law.

San Joaquin River

Most people think of agriculture when they think of the San Joaquin River. They don’t consider king salmon swimming upstream through cool waters to spawn on the high slopes of the southern Sierra Nevada, or vast wetlands supporting millions of waterfowl and even elk herds. But they should.

The hardest working river in California originates from headwaters that include Yosemite and Kings Canyon National Parks and the Ansel Adams Wilderness. Principal tributaries like the Tuolumne and Merced provide inspiring reminders of what the 366-mile river coursing through the fertile San Joaquin Valley south of Sacramento once offered, and may yet offer again.

The river meets the other half of the state’s largest watershed at the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta where the combined rivers flow west through the Carquinez Strait into San Francisco Bay.

An abundance of wildlife depends on this river, including a significant portion of the Pacific salmon fishery that once flocked upstream by the millions. The breadth of the watershed supports a recreation industry that generates billions of dollars in economic activity and includes world-class whitewater paddling, salmon and trout fishing, and waterfowl hunting.

They also support some of the most productive and profitable agriculture in the world, irrigating more than two million acres of arid land. The rivers generate enough hydropower for more than 4 million homes, and provide drinking water to over 25 million people, including the cities of San Francisco and Los Angeles.

Did You know?

Before agricultural development of its valley, the San Joaquin was navigable by steamboats as far upstream as Fresno.

At 31,800 square miles, the San Joaquin watershed is the largest single river basin entirely in California, comparable in size to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan.

The Sacramento, when combined with the Pit, is one of the longest rivers in the United States entirely within one state. Only the Kuskokwim in Alaska and the Trinity in Texas are longer.

Groundwater withdrawal has led to land subsidence of more than 28 feet in the San Joaquin Valley near Mendota.

The Sacramento supports nearly 60 species of fish and 218 types of birds. Native bird populations on the river have declined steadily since the 19th century.

The Backstory

Humans have not treated these rivers well through the years. More than a century of managing them for agriculture, hydropower, and flood control has taken its toll. The health of the San Joaquin River has suffered the impacts of hundreds of dams, levees stretching thousands of miles, and countless water diversions. More than 95 percent of floodplain and freshwater tidal marsh habitat has been converted to development or agriculture. Once-iconic salmon runs teeter on the brink of extinction.

The problems are so acute that American Rivers named the San Joaquin River one of America’s Most Endangered Rivers® in 2014. In 2016, it rose to the No. 2 position on the list.

Man’s manipulation has severely hurt river habitat and opportunities for recreation and community access. More than 100 miles of the San Joaquin’s main stem have been dry for over 50 years, and water diversions along the tributaries take more than 70 percent of the natural flow. Before irrigation development, the river and its tributaries once supported the third-largest run of Pacific salmon in California, measuring more than 200,000. Today, the few remaining fish have nowhere to go.

People are at risk as well. Outdated approaches to water management have made communities vulnerable to increasingly frequent and severe droughts and floods.

The Future

There is hope on the horizon, however. California has never experienced a greater opportunity to address these threats and American Rivers is already hard at work.

There are many reasons for optimism. Voters recently passed a $7 billion “Water Bond” designed to jumpstart critical improvements to fisheries, habitat, flood safety, and water quality. The State Water Board is developing a new plan to meet water quality standards and protect the public values provided by the San Joaquin, Sacramento, and Delta watershed. More than two dozen dams must get new operating licenses that better protect rivers, native fish and water quality. The Central Valley Flood Protection Plan will be updated in 2017.

All that adds up to more water in the rivers. The Water Board must act this year to increase flows in the San Joaquin so that the watershed is healthy enough to support fish and wildlife, sustainable agriculture, and resilient communities for generations to come. In order to comply with state and federal laws, the Board must require dam owners to release more water to the river in a manner that mimics the natural flow regime.

Meanwhile, American Rivers has embarked on multi-benefit projects on the San Joaquin designed to enhance flood safety and restore salmon-rearing habitat by reconnecting the floodplain. Projects designed to improve water quality, increase water quantity, and improve quality of life by establishing the river as a more vibrant community asset are also underway.

While drought and climate change are affecting water patterns, they are also teaching Californians to adapt, improve groundwater storage and figure out ways to make a finite resource stretch farther. The San Joaquin River and the communities that depend on them are currently being acted upon by a confluence of forces that will create opportunities for historic success, or epic failure.

San Miguel River

Like many Southwest rivers, the San Miguel River moves in steep and dramatic motions from alpine to arid. With origins at nearly 13,000 feet in the Southern San Juan Mountains, and lower reaches that weave through red river canyons, the San Miguel flows freely for nearly 81 miles before converging with the Dolores River along the Colorado/Utah border.

Did You Know?

During the late 1800’s, the San Miguel River was channelized in the Telluride Valley Floor to make more lands accessible for flooding and agriculture. In 2016, the Town and partners of Telluride completed a project aimed at restoring the river’s original character. They added nearly 1,300 feet to renew its original sinuosity, and now, with the beavers, the river is functioning more like it did before settlement.

Approximately 62 percent of the San Miguel Watershed is publicly owned

Approximately 9 percent of the total watershed is used for agricultural purposes

What Can I Do to Help?

Stay informed with what is going on with rivers across the Southwest by following our Southwest River Protection Program.

Tell the Trump Administration to retain and support the Waters of the United States rule under the Clean Water Act. Take action here.

WHAT STATES DOES THE RIVER CROSS?

Colorado

One of the last free-flowing rivers in the Southwest, the San Miguel’s complex character marks a birth among alpine wildflowers before the river topples over Bridal Veil Falls and winds through the Telluride Valley Floor. The river meanders through the high mountain valley, where bike paths and signs celebrate its recently restored sinuosity. Between Sawpit and Placerville, the river flows past the Angler Inn where avid fly-fishers catch rainbow and brown trout. Before converging with the Dolores River, and then on to the Colorado River, the San Miguel moves through San Miguel and Norwood canyons—providing phenomenal Class I – Class IV runs for boating enthusiasts. Birders come to the shores of the river to watch American dippers nest along the canyon walls.

The San Miguel is one of the few naturally functioning rivers in Colorado, and the Southwest, providing most of the water that maintains the imperilled Dolores River through its lower canyons. More than 30 miles of the San Miguel River are protected in preserves, largely because of the important and rare riparian habitat the river’s natural hydrograph and limited development provide and protect. Narrowleaf cottonwood, Colorado blue spruce , and thinleaf alder are just a few of the important forest species that thrive in the steep canyons of the San Miguel.

The San Miguel’s cool, clean water provides a rare refuge for native fish. Cold water mottled sculpin and cutthroat trout make home on the cobbled river bottom. Seven genetically pure populations of cutthroat thrive in its waters. Downstream, warm water fish like the roundtail chub, flannelmouth sucker, and bluemouth sucker rely on consistent flows throughout the season for reproduction.

In 2015, the Colorado Supreme Court upheld the instream water rights for the San Miguel river, approving protections for up to 325 cubic feet per second in-stream flows to protect fish and wildlife. Faced with warming temperatures and decreasing snowpack under future climate conditions, and threatened by growing demand, the future of the small but critical river remains tenuous. American Rivers and our local and regional partners are working to better understand and identify ways to keep the river functioning in the decades to come through participation in stream management planning.

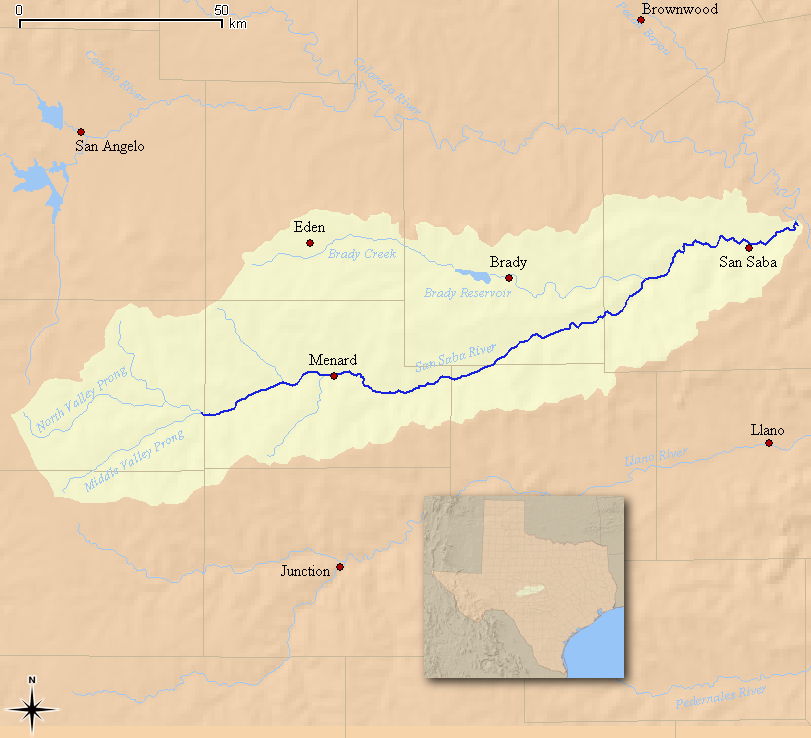

SAN SABA

The San Saba River is a scenic waterway located on the northern boundary of the Edwards Plateau in Texas. Flows of sparkling, clear water course through limestone bluffs and hills, supporting fish, wildlife, and recreation. Through wasteful water use and unregulated pumping, irrigators are transforming a vibrant, pristine river into a dried-up riverbed.

The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality must enforce the law to ensure adequate flows are maintained. Further, the Texas Legislature should appoint a watermaster on the upper stretch of the San Saba River to better manage flows and protect the river long-term.

Threats to This River

Texas law provides that all natural surface water found in rivers is owned by the state and is held in trust for its citizens. There are no sealed meters and no accurate methods for the state to know whether irrigators around Menard, Texas, are exceeding their allowed limits.

Excessive pumping for agricultural irrigation has been diverting the river’s flow into a canal (where 30 percent or more is lost due to evaporation and leaks). Moreover, some irrigators place extremely shallow wells next to the river to pull water from the river under the guise of groundwater wells. This unregulated pumping in the last twelve years has almost dried up over 50 miles of the river for an average of five months of the year. This hurts downstream ranchers who need water, damages the river ecosystem, and negatively impacts the Austin chain of lakes.

While pumping is certainly legal by permitted landowners, such permit holders are required to leave a flow in the river sufficient to service the domestic and livestock users downstream. In 2011, after priority calls were made by ranchers, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) did the right thing and suspended pumping. The river filled up and flowed again despite irrigators’ claims that it was drought– not excessive pumping– that had dried up the river. When irrigators pumped the river dry again in 2012, the TCEQ inexplicably denied the priority calls from downstream ranchers, refusing to enforce the law because they claimed they did not feel the suspension would result in restored river flows. This position was puzzling since the flow returned to the river after the suspension in 2011– the year of the worst drought in more than 60 years.

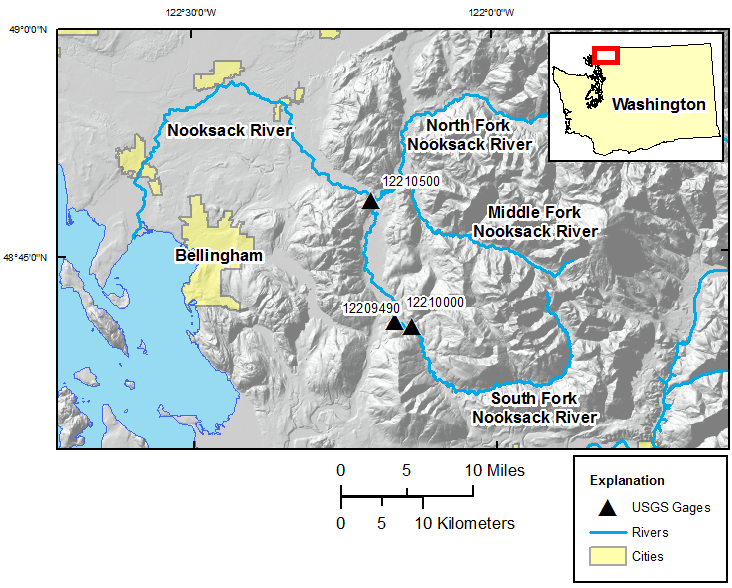

Nooksack River

The only thing it lacks is the Wild and Scenic label

The Nooksack River puts the great in the Great Northwest. Its spectacular North Fork is the northernmost river in Washington, running wild with icy glacial snowmelt from the snowfields of 10,778-foot Mount Baker and 9,127-foot Mount Shuksan in North Cascades National Park, before being joined by the Middle and South forks as it weaves through forests and farmlands on its way to the Salish Sea in Puget Sound north of Bellingham.

With volcanic Mt. Baker and the Twin Sisters Range of the jagged North Cascades dominating the surrounding landscape, the upper river was shaped as much by fire as ice through the millennia, creating a one-of-a-kind watershed treasured for its vast array of scenery and recreation. Whether it’s whitewater paddling beneath (or skiing atop) towering snowcapped summits; fishing in ancient forests for five species of native salmon, steelhead, resident rainbows, and cutthroat trout; hiking past waterfalls on the nearby network of trails; or scoping out abundant bald eagles, black bears, mountain goats, elk, spotted owls and even the rare bull trout, the Nooksack does not disappoint.

If there is a downside, it is found in lack of permanent protection for this great Northwestern treasure. Such high-quality habitat is increasingly rare and valued by millions for the clean water it provides for drinking, farming, outdoor recreation, and tourism. A cultural mix of native tribes, heritage farm towns, burgeoning New West communities, and the wildlife surrounding them all depend upon an unspoiled Nooksack River connecting glacial headwaters with the sea. Yet the majority of this vital river system remains deprived of even the most fundamental protection.

Did You know?

Mt. Baker (feeding the Nooksack River) is one of the snowiest places in the world. In 1999, Mt. Baker Ski Area set the world record for recorded snowfall in a single season—1,140 inches.

The endangered Marbled Murrelet is a small Pacific seabird that nests in old growth forests surrounding the Nooksack but has declined in numbers since humans began logging in the region.

The Nooksack Indian Reservation is in Whatcom County Washington. Whatcom was the name of a Nooksack chief and means “noisy water” in the Nooksack language.

What states does the river cross?

Washington

Other Resources

Check out these other resources to learn more about the river:

Nooksack Wild and Scenic Campaign website

The Backstory

The Nooksack Wild and Scenic effort is about conserving the ecological and recreational values of this magnificent river system. A diverse array of interested citizens, business owners, and organizations has worked for years to build widespread public support for Wild and Scenic River legislation designed to permanently protect over 100 river miles and 32,000 acres of riverside habitat in the upper Nooksack basin, including portions of all three forks and eight tributary streams.

Like much of the Northwest, some 40 hydroelectric dams have been proposed for various sites on the Nooksack since the 1970s, the legacy of logging impact remains along portions of the river, and a diversion dam on the Middle Fork has blocked passage of salmon and steelhead for nearly 70 years. Tremendous efforts are underway to restore the ecological health and improve the habitat of the Nooksack River and protecting the headwaters as Wild and Scenic would help protect these investments in restoration.

The Future

Keeping the Nooksack great remains a top priority in the region. Wild and Scenic designation would ensure that the river’s “Outstandingly Remarkable Values” are protected and enhanced in the future and prevent any new dams or other projects that would degrade the river’s natural character and healthy flows. The Nooksack Wild and Scenic campaign is working toward drafting legislation by 2017.

Recreational access around the river corridor is also a major concern and American Rivers is working with a variety of partners to implement recommendations in the Upper Nooksack River Recreation Plan, a planning effort spearheaded by American Rivers intended to improve access and guide recreational use in the region for the next 10-15 years. American Rivers is also an advisory committee member on Washington Department of Natural Resource’s new recreation planning effort called the Baker to Bellingham Recreation Plan.

In late 2020, American Rivers worked with several partners including Washington State Department of Natural Resources, Whatcom Land Trust, the Nooksack Tribe, American Whitewater, and others, with technical assistance from the National Parks Service, to finalize a plan for the Maple Creek Public River Access and Restoration Site. This site was identified in the Upper Nooksack River Recreation Plan as an ideal location for safe public recreation access along the North Fork Nooksack River, while also allowing natural resource managers to protect, restore, and enhance the adjacent riparian forest and natural river systems.

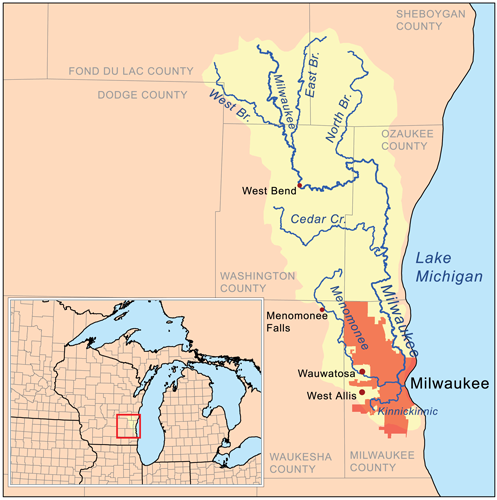

Kinnickinnic River

At 33 square miles and 96 percent urban land cover, the Kinnickinnic River is the smallest and most developed watershed in the Milwaukee River basin — a watershed that covers approximately 850 square miles and is home to more than 1.5 million people.

The Kinnickinnic River, which lies almost entirely in the city of Milwaukee, empties into the Milwaukee Estuary and then Lake Michigan.

The entire Milwaukee Estuary has been designated as a Federal Area of Concern (AoC), including 2.8 miles of the Kinnickinnic River from Lake Michigan to Chase Avenue, due to toxic contaminants and urbanization of the river. The Kinnickinnic River is located in one of the most populated, racially diverse and poorest areas of the city of Milwaukee.

The communities around the river endure poor water quality, a lack of recreational opportunities, and diminished and unsafe access to the river. Once consisting of a vast marsh, a vibrant crawfish fishery and multitudes of shipyards, the river still remains vital to the local boating industry, though the build up of contaminated sediment severely hampers all boating activities, both recreational and commercial.

Threats to This River

Like many urban rivers across the country, the Kinnickinnic River has been neglected — laced with toxic contamination, lined with concrete, degraded and ignored. Extensive efforts and studies have highlighted these problems, and many local organizations and agencies have made Kinnickinnic River restoration a top priority.

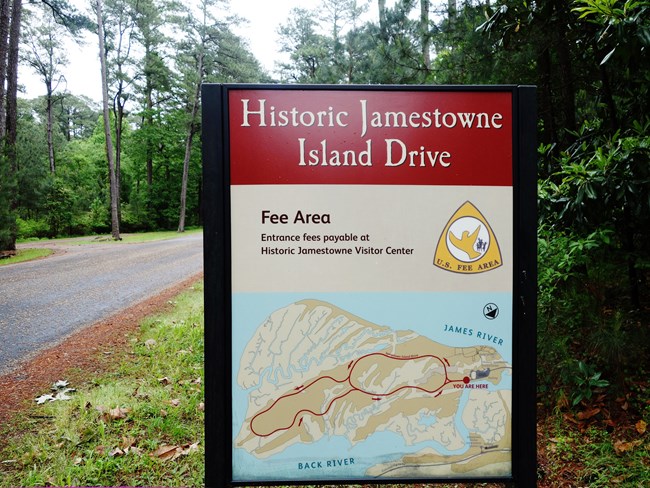

James River

America’s “Founding River”

The James is known as America’s “founding river” because it was the site of the first permanent English colony at Jamestown in 1607 and home to Virginia’s first colonial capital at Williamsburg. Indigenous people lived in Virginia for 16,000 years before colonists arrived. The tribes of the Powhatan Confederacy settled in villages near the James, and the river served as a transportation corridor for Native Americans and early colonists. The James River was the site of critical battles in the Revolution and the Civil War.

Today, the James River watershed spans 39 counties and 19 cities and towns. One-third of all Virginians live in the James River watershed and rely on the river for drinking water, recreation, and commerce. The James River area attracts more than 3.5 million visitors every year. The river is part of the Captain John Smith Water Trail, designated as the first national water trail in 2006.

In 2024, Richmond was voted as the No. 1 on the America’s Best Towns to Visit list, thanks in large part to the many recreational benefits provided by the James River. Richmond has since emerged as a creative hub, with the James River playing a significant role in its cultural renaissance. The river’s proximity to the city has inspired countless artists, musicians, and entrepreneurs, making it a focal point for creative expression and innovation. The riverfront has become a vibrant area, hosting festivals, art installations, and outdoor performances, further solidifying Richmond’s reputation as a cultural and creative center in the Mid-Atlantic region.

The James is critical habitat for Atlantic sturgeon, a species that has existed for 120 million years, and is one of the largest roosting areas on the eastern seaboard for bald eagles. The river’s diverse ecosystems support a wide range of species, and ongoing conservation efforts aim to protect these habitats from the pressures of urbanization and climate change. The James River is also an essential corridor for migratory birds and other wildlife, providing critical connections between various ecosystems across the state.

American Rivers, working with our partners, seeks to protect the James River and its key tributaries to conserve the ecological, recreational, and community benefits they provide.

The National Park Service has found that the James is “one of the most significant historic, relatively undeveloped rivers in the entire northeast region.” The river’s historical and cultural significance continues to grow as Richmond’s creative community draws inspiration from its natural beauty and rich history, further emphasizing the need for its protection.

Because of these outstanding qualities, the Park Service found the James River and some of its high-value tributaries eligible for Wild and Scenic River designation as a part of its Nationwide Rivers Inventory. The agency determined that these rivers are free-flowing and have outstanding values of national or regional significance that warrant their inclusion in the National System of Wild and Scenic Rivers.

The Maury and Rivanna Rivers, two high-value tributaries of the James River, also qualify as free-flowing and have several outstandingly remarkable values, including recreation, fisheries, and scenery. Protecting these tributaries will help prevent further degradation of the James River from harmful development and other threats.

Portions of the James River and its tributaries are prime candidates for the Partnership Wild & Scenic Rivers Program, a successful model of designation that helps communities preserve and manage their own river-related resources locally by bringing together state, county, and community managers. Somewhat different from traditional Wild and Scenic River designation, the Partnership Program protects nationally significant rivers that flow through privately-owned or state-owned lands.

Transmission Lines

American Rivers has been supporting efforts challenging Dominion Energy’s transmission lines across the James River. The massive power lines and 17 transmission towers harm the integrity of this unique landscape and historic viewshed. This stretch of the James is listed in the Nationwide Rivers Inventory and has been found to have “outstandingly remarkable” historical values.

Despite strong public opposition, the Army Corps of Engineers granted a permit to Dominion Energy to construct the power lines in 2017 – but the Army Corps did not require an Environmental Impact Statement. Dominion proceeded with construction, while our partners challenged the permit in court. American Rivers filed a friend of the court brief in support of the National Parks Conservation Association, arguing the Army Corps violated the National Environmental Policy Act. The transmission lines were completed while the legal battle continued.

In February 2019, the U.S. Court of Appeals ruled that the Army Corps violated federal law and ordered the Army Corps to prepare an Environmental Impact Statement.

“The public is deeply connected to this area and the river due to its historical significance and aesthetic beauty. We need to work together to protect the Commonwealth’s priceless heritage and America’s Founding River.”-Bob Irvin, Former President of American Rivers

American Rivers has urged the Army Corps to consider energy demand, endangered species, and the Clean Water Act as well as to ignore any costs for the removal of the transmission lines and related infrastructure. Those costs were incurred after Dominion assured the District Court for the District of Columbia and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit that any construction could easily be reversed if it was found that the transmission towers and accompanying infrastructure were installed under the auspices of an unlawful permit.

“Sustainable power production and transmission are critical needs, but it’s important we look at alternatives that can serve the region’s evolving needs while preserving the character and values of the James River. The public is deeply connected to this area and the river due to its historical significance and aesthetic beauty,” said Bob Irvin, President of American Rivers

Holston River

The Holston River begins in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains and flows for 274 miles through Virginia into Tennessee. The river ends at the confluence of the Holston and French Broad rivers to form the Tennessee River. It is home to 47 species of fish including smallmouth bass, brown trout, rainbow trout, redline darter, and bigeye chub.

The Holston River has played an important role in the history of East Tennessee from prehistoric times to today. In 1791, the Treaty of the Holston was signed between the United States and the Cherokee Indian Nation establishing that the U.S. would protect and manage the affairs of the Cherokees. Many Civil War battles were fought along the banks of the Holston, as the river had great strategic importance for commerce in the Tennessee Valley.

In the 1940’s and 50’s, the Tennessee Valley Authority built four dams on the Holston River to provide electricity and flood control. Today, the river is the most important source of drinking water for many communities that border the South Holston River in Tennessee, as well as a place for fishing and recreational use.

Hitchcock Creek

Hitchcock Creek, a tributary of the Pee Dee River, flows through Rockingham, North Carolina. Thanks to a recent dam removal and the creation of a blue trail, the creek is experiencing a renaissance and the local community is reconnecting to this valuable natural asset.

Threats to This River

Until 2009, the Steeles Mill Dam degraded Hitchcock Creek, blocking migrating fish and preventing the community from safely enjoying the river through recreation. In June 2009, removal of Steeles Mill Dam began, marking a renaissance for Hitchcock Creek, and emblematic of a river restoration trend in North Carolina and nationwide.

What states does the river cross?

North Carolina

Originally built in the late 1800s to generate power for a cotton mill, the 15-foot tall Steeles Mill Dam had fallen into disuse by 1999. The removal of the dam restored more than 15 miles of habitat for species including hickory shad, blueback herring, striped bass and Atlantic sturgeon. The dam removal was the result of efforts by partners including American Rivers, the City of Rockingham and NOAA.

“This is the beginning of a great new chapter for Hitchcock Creek and nearby communities,” said Gerrit Jöbsis, Southeast regional director for American Rivers, at the time of the dam removal. “Healthy rivers are the lifeblood of our communities and it is hard to overstate the many benefits they provide. When we tear down old infrastructure like obsolete dams, we build up our natural infrastructure – the streams, wetlands and floodplains that give our communities essential services like clean water, flood protection, and other economic benefits.”

HITCHCOCK CREEK BLUE TRAIL

Following the dam removal, American Rivers worked with the City of Rockingham to create a new 14 mile blue trail from Ledbetter Lake to the Pee Dee River. Blue trails, the water equivalent to hiking trails, are created to facilitate recreation in and along rivers and other water bodies. They can stimulate local economies, encourage physical fitness, improve community pride, and make rivers and communities healthier.

“This isn’t just about removing a dam, it’s about revitalizing Hitchcock Creek into an even greater asset for our community. We are excited about the creation of a new blue trail, and the economic, recreation, and quality of life rewards that will bring. Soon, a healthy Hitchcock Creek will be a source of pride for all of us, and residents and visitors alike will be able to reap the benefits,” said Gene McLaurin, the Mayor of Rockingham.

As small communities around the country struggle to grow their economies, the city of Rockingham has recognized the ability of restoration projects to inject new dollars into the community. Projects such as these can lead to greater economic stability over the long term by restoring commercial and recreational fishing, improving tourism, and creating new business and recreation opportunities. Community liabilities can be remade into community assets.

As part of this effort, the City of Rockingham protected 100 acres of bottomland forest along the Blue Trail, purchased two river access areas, and acquired a boat launch.

HAW RIVER

The Haw River flows 110 miles from its headwaters in the north-central Piedmont region of North Carolina to the Cape Fear River just below Jordan Lake Reservoir. The river and its watershed provide drinking water to nearly one million people living in and around the cities of Greensboro, Burlington, Chapel Hill, Cary, and Durham. This 1700 square mile watershed is home to a variety of fish and wildlife, including blue heron, bald eagle, beaver, deer, otter, largemouth and smallmouth bass, bowfin, crappie, carp, and bluegill. The Haw also contains important habitat for the endangered Cape Fear shiner and an assortment of rare freshwater mussel species.

Local residents appreciate the Haw for its outdoor recreational opportunities, including hiking, paddling, swimming, fishing, and picnicking, as well as the solitude and quiet the river offers. The Haw River is the most popular whitewater paddling river in the North Carolina Piedmont Region, and Jordan Lake (a 14,000 acre reservoir) provides recreation for about 1 million visitors a year for boating, swimming, camping, and fishing.

The Backstory

The Haw River has been the victim of death by a million cuts. Millions of gallons of wastewater and polluted runoff (i.e., rainwater that picks up pollution as it flows over roads and parking lots) have washed into the Haw. Population growth since the 1960s has overwhelmed the systems put in place to protect clean water. Aging pipes and infrastructure result in raw sewage spills and the increased development has made flooding worse and added pollution to the rivers across the watershed. This pollution has caused large algal blooms in backwaters along the river and is a major contributor to the problems that inflict Jordan Lake Reservoir, a major drinking water reservoir near the end of the watershed, impacting the health of people and the ecosystem that depends on it. In 2014, American Rivers listed the Haw River as a Most Endangered River to highlight the problems that the river faced.

There are dozens of small dams in the watershed. They had powered the initial industrial revolution in the watershed and have primarily fallen into disrepair and have been abandoned by their owners. These dams fragment rivers, devastate fisheries and disrupt natural river functions. They also create a significant hazard to communities as the pools behind them create inviting places to swim but the hydraulics in front of them will suck a person in and likely drown them.

The Future

The Haw River has caught the attention of the community around it- with places like Saxapahaw centering much of their community and economic growth on the health of the river. North Carolina has developed a clean-up plan for the problems seen in the Jordan Lake Reservoir but that plan has not been able to be fully implemented and missed the opportunity to engage the entire watershed and bring the values of a healthy river system to all the communities in the watershed.

In 2015, American Rivers led the development of a new approach to managing water in the Haw River. This new approach was based on the principles of Integrated Water Management or One Water that looks to find the value in all water (stormwater, drinking water, reclaimed water, wastewater, etc.) This creates management efficiencies that save money and reduce regulatory burden while producing more ecological benefits.

The Jordan Lake One Water (JLOW) initiative was launched in 2017. It brought together communities from across the watershed from Greensboro to Cary and interest groups from across the spectrum include other environmental advocates, Farm Bureau, NC Home Builders, and private businesses. The group is working to eliminate the silos dividing the work that each of the groups is doing and finding new partnerships and greater investment in strategies that restore the ecological health- and therefore the economic health- of the watershed. This system will invest in projects and develop policies that build resilience in the watershed to climate change including the impacts from flooding and droughts, builds community stability and opportunity, reduces pollution of all sorts going into the streams across the watershed, and restores the ecosystem of the watershed.

This attention to the river has also helped to encourage a greater interest in recreation and reconnecting the river by removing the antiquated dams that dot it. We’ve removed several remnant dams- the Upper Swepsonville dam and the Granite Mill dam– to restore the river. We hope to work with more communities and dam owners to find the long-term sustainable restoration solutions for many of the remaining dams in the system.

Harpeth River

The Harpeth River flows 125 miles from its headwaters in Eagleville to its confluence with the Cumberland River.

A portion of the Harpeth is designated a State Scenic River as it flows through the Nashville metro area, and a series of state, county, and city parks along the Harpeth connect natural, archaeological, and historic sites.

Due to its natural beauty and proximity to a major urban area, countless paddlers, anglers, and other outdoor lovers enjoy the river every summer.

The Harpeth River and its tributaries are home to rich freshwater biodiversity, including more than 50 species of fish and 30 species of mussels. Several of these species are classified by Tennessee as rare and in need of management, and two mussel species are protected under the Endangered Species Act. The Harpeth also played a major role in the Battle of Franklin 150 years ago, a battle that determined the outcome of the Nashville Campaign, and ultimately the western theater of the Civil War.

Threats To This River

The Harpeth River flows through the heart of downtown Franklin, the 14th fastest growing city in the United States, and traverses Williamson County, one of the fastest growing counties in Tennessee. This rapid development has already caused harm to the river from adding treated sewage, increasing stormwater runoff, and withdrawing water. If not managed responsibly, it could cause irreparable damage to the river.

Since the state of Tennessee first issued its required 303(d) list of impaired waters in 1999, the Harpeth has been listed because the river frequently fails to meet water quality standards for fish and aquatic life and recreational use during periods of low summer flow. Nearly 60 percent of the entire length of the main river is impaired, along with 37percent of its more than 1000 miles of tributary streams.

The river’s impairment is caused by dangerously low levels of dissolved oxygen driven by high concentrations of nutrients – particularly phosphorus – that fuel oxygen-hungry algal blooms that can lead to toxic conditions. Primary sources of nutrient pollution include treated sewage effluent and stormwater runoff. During summer months when the river experiences natural low flows, sewage effluent can dominate the river and significantly contribute to the total nutrient load downstream from the City of Franklin’s sewage treatment plant. For example, on average in August 2014, downstream from the sewer plant, 32 percent of the river’s total flow came from treated effluent that contained phosphorus levels 3.5 times higher than the river’s levels just upstream, according to the city’s own data.

The pollution problem is exacerbated by the City of Franklin’s aging 2 million gallons-a-day drinking water plant that withdraws water from the river not far upstream from its sewer plant. The city wants to replace its plant even though the Harpeth is too small to supply the city with its drinking water needs. The city’s primary, and most reliable, source of drinking water is a substantial utility that produces water from the much larger Cumberland River. This utility provides three-fourths of the city’s annual demand and up to 100 percent during the summer or when the city’s plant is down. Meanwhile, the city withdraws up to 20 percent of the Harpeth’s flow during low flow periods. According to the state, this is problematic for fish and aquatic life, and reduces the capacity of the river to handle the city’s treated sewage discharges and other pollutants downstream.

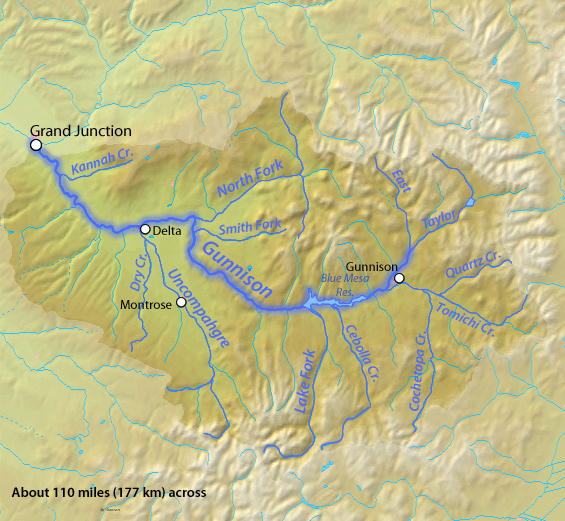

Gunnison River

Thoroughly Western

From the heart of Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park, it’s easy to appreciate the raw power of the Gunnison River. Monolithic walls of ebony schist, slashed by veins of granite, and carved to depths of more than 2,000 feet tell the tale of 2 million years of the mighty Gunnison relentlessly churning through mountains of stone.

The abyss was considered impassable by anything but the river until 1901, when a team of surveyors hiked through and mapped out plans for a 5.8-mile diversion tunnel that still shuttles more than 300,000 acre-feet of water from the Gunnison to a smaller tributary in the Uncompahgre Valley every year. Upstream of the Black Canyon, dams have impeded the once wild river’s passage, creating a series of storage and hydropower reservoirs, including Colorado’s largest at Blue Mesa.

The state’s second largest river still has its moments, though. Between its headwaters along the Continental Divide and its confluence with the Colorado River near Grand Junction, the Gunnison alternates between pristine trout fisheries, public recreation areas, heritage ranches, and tumultuous whitewater fed by snowmelt runoff from some of the tallest mountains in the Rockies. Robust herds of mule deer and North American elk roam the surrounding forests and peaks with bears, mountain lions, and bighorn sheep.

Below the town of Gunnison, Blue Mesa Reservoir holds trophy mackinaw and the state’s largest population of kokanee salmon, which migrate upstream every autumn to the delight of anglers and eagles alike. Downstream of the dams, world-class rock climbing, paddling, scenery and Gold Medal trout fishing draws visitors from around the country to the Black Canyon and more accessible Gunnison Gorge just above the confluence with the river’s North Fork.

The focus is on agriculture in the lower basin, delicately balanced against the needs of several species of fish listed under the Endangered Species Act. By the time it connects to the Colorado River, the Gunnison will have drained nearly 8,000 square miles of rugged terrain in rural western Colorado, though its renown reaches far beyond.

Did You know?

Among all the tributaries to the Colorado River, only the Green River is bigger than the Gunnison in terms of water contributed.

The Black Canyon of the Gunnison was named a national monument in 1991 before Congress declared it a national park in 1999.

Although its headwaters originate along the Continental Divide, the Gunnison formally begins at the confluence of the Taylor and East Rivers south of Crested Butte.

Both the river and town are named for Lieutenant John Gunnison, an engineer sent to survey a railroad route across the Rockies in 1853.

other resources

Check out these other resources to learn more about the river:

What states does the river cross?

Colorado

The Backstory

To protect “the roar of the river,” President Herbert Hoover declared the Black Canyon a national monument in 1933. In 1999, Congress declared it a National Park. Though beautiful and partially protected, the Gunnison River has been starkly impacted by man nonetheless.

Three dams operated by the Bureau of Reclamation just upstream from the park have severely altered the natural flow of the river. The Aspinall Unit, as the dams are collectively known, inundated more than 40 miles of prime native trout waters to allow more consistent control of the river’s water for irrigation and hydropower.

After being named America’s Most Endangered River® in 1991 and returning to the list at No. 4 in 2003, a coalition of stakeholders and litigators hammered out a decree to protect the natural values of the Black Canyon in 2008. Decades of conflict eventually resulted in water rights that now promise a spring peak flow, shoulder flows and base flows critical to the health of the river.

The Future

Like other rivers in the Southwest, the Gunnison suffers from periodic drought, placing stress on agriculture, fish, and habitat. But water users throughout the basin are proactively addressing these challenges by installing water-saving irrigation infrastructure, investigating water sharing opportunities, and promoting in-stream flow protections, particularly at critical headwaters. Delta County, in the basin, is piloting a new agricultural hydropower program focused on pressurized sprinkler irrigation rather than flood irrigation in order to spur water conservation.

The Gunnison River is one of the last major sub-basins in Colorado that has not been diverted to provide water to ballooning Front Range communities, marking it as a potential target for the future. A major diversion out of the basin would have severe impact on fish, wildlife, agriculture and a growing recreation economy. For now though, the resilient river endures.