Patapsco River

Say Can You See?

Without the Patapsco River, America wouldn’t have its National Anthem. Baltimore wouldn’t have its Inner Harbor and Maryland wouldn’t have its first state park. Talk about a powerful river.

The mouth of the Patapsco River forms Baltimore Harbor, the site of the Battle of Fort McHenry, where Francis Scott Key wrote “The Star-Spangled Banner” aboard a British ship during the War of 1812. Today, a red, white, and blue buoy marks the spot where the HMS Tonnant was anchored.

The river’s more popular association is upstream of Baltimore at Patapsco Valley State Park, however. With recreational opportunities including hiking, fishing, camping, canoeing, horseback riding, mountain biking, and picnicking along a 32-mile segment of the Patapsco and its branches, the park was officially celebrated as Maryland’s first in 2006.

The park’s history traces back more than a century, though, intimately intertwined with the river itself. Completion of Bloede Dam on the Patapsco in 1906 required protections to prevent silting from nearby farms, and the area was established as Patapsco State Forest Reserve in 1907 to protect the valley’s forest and water resources. Now known as Patapsco Valley State Park, it has grown to 16,000 acres highlighted by a rocky gorge cut by the river some 200 feet deep and laced with cliffs and tributary waterfalls.

The river’s entire main stem flows fewer than 40 miles from Mariottsville through Elkridge, Ellicott City and other Maryland towns, drawing from a watershed of just 680 square miles, before it reaches the harbor and the Chesapeake Bay. Yet it remains one of the Baltimore area’s hidden jewels, providing the people of Maryland with a favorite fishing hole, Class I-II canoe and kayak rapids, trails to wander, and cool relief from the summer heat.

Did You know?

Francis Scott Key wrote the poem that later became the “Star-Spangled Banner” during the Battle of Ft. McHenry at the Patapsco River mouth in the Baltimore Harbor.

Bloede Dam, in Patapsco Valley State Park, was the first known instance of a submerged hydroelectric plant, where the power plant was actually housed under the spillway. The dam is scheduled for removal by July, 2017.

In 1999, final scenes of The Blair Witch Project were filmed in the Griggs House, a 200-year-old building located in Patapsco Valley State Park near Granite, MD.

What states does the river cross?

Maryland

The Backstory

Many historians consider the Patapsco River flowing through Baltimore one of the birthplaces of the Industrial Revolution, and dams built along the waterway were important sources of power. Bloede Dam was the first hydropower dam in the U.S. where the turbines were housed internally. However, as with many things, the Patapsco dams became obsolete as industry pivoted to other ventures.

Yet the old Patapsco dams continued to disrupt the natural function of the river and block passage for migratory fish like shad and river herring, and American eel. The dams also posed a safety hazard for paddlers, swimmers, and fisherpersons in Maryland’s most visited state park, which resulted in several deaths at Bloede Dam over the years.

Working with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Friends of the Patapsco Valley State Park, and many other partners, American Rivers has helped spur the removal of three of the Patapsco River’s four major dams—the Union Dam in 2010,the Simkins Dam in 2011, and the Bloede Dam in 2018—and is investigating the potential removal of the Daniels Dam, currently the farthest downstream dam on the Patapsco. Removal of Daniels Dam would complete the reconnection of more than 65 miles of the river and its branches, with only the upstream Liberty Dam remaining (currently providing water supply to the City of Baltimore and not slated for removal).

Although largely protected and hopefully soon to be reconnected, the Patapsco still suffers on its highly urbanized eastern end, which empties into Baltimore Harbor. Stormwater runoff and other forms of water pollution are exacerbated by aging infrastructure, often leading to hazardous water quality. Local infrastructure has been challenged by extreme weather events, leaking as much as 100 million gallons of sewage into the river during major storms.

The Future

American Rivers has been working for more than a decade on the Patapsco River Restoration Project which is benefitting water quality, river safety, native fish and wildlife, and the overall health of the river and the Chesapeake Bay downstream. This project is a priority for American Rivers and our partners because it addresses the three major crises impacting rivers across the country—biodiversity, climate change, and environmental justice.

The Patapsco River Restoration Project is more than just a dam removal project. It is an opportunity for collective visioning about the future of Patapsco Valley State Park. With millions of visitors annually, it is important to consider the needs of the park users and the local community. These projects build upon the great work of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources to support the park, as well as local groups such as Friends of Patapsco Valley State Park and Patapsco Heritage Greenway. American Rivers hopes to engage other groups as well, as we work towards a free-flowing Patapsco River.

Running through Ellicott City and ultimately down into Baltimore Harbor, the Patapsco River is uniquely situated to connect people and nature— healing the scars of an impaired industrial landscape and exploring how to live in harmony with the river and what that looks like for different communities. We hope to talk with a broader audience about this special place and help more people connect with the river.

For more information, contact Jessie Thomas-Blate with American Rivers at info@americanrivers.org.

Rio Grande

IN HIGH DEMAND

Will Rogers once described the Rio Grande as “the only river I know of that is in need of irrigating,” a prescient observation considering how fragmented this fabled river has become. At nearly 1,900 miles, the Rio Grande is runner-up only to the combined Missouri-Mississippi system in length within the continental U.S. Or it would be, if it still flowed the length of its channel.

Rio Grande, Rio Bravo, El Rio Bravo del Norte, The Rio. Whatever you call it, however you know it, the Rio Grande, at nearly 2,000 miles long, is the 3rd longest river in the continental US, and a source of life for the more than 6 million people and countless wildlife species and ecosystems that rely on it. It is one of the most important rivers in the Southwest, supporting communities, agriculture and ecosystems in Colorado, New Mexico, Texas and the Republic of Mexico. From its headwaters to its terminus in the Gulf of Mexico, communities rely on the Rio and its tributaries for drinking water, agriculture, abundant recreation, habitat for birds and is quite literally the backbone of local economies.

This immensely critical but often overlooked river originates in the alpine ranges of the San Juan Mountains in southern Colorado. It flows east and south through the agriculturally rich San Luis Valley into New Mexico, eventually entering Texas at El Paso then forming the border with Mexico as it flows east through Big Bend National Park and on to its terminus with the Gulf of Mexico just east of Brownsville.

Like many of the Southwest’s rivers, the Rio Grande is critical to the livelihood of communities along its banks, but is under increasing pressure. Climate impacts, coupled with the fact that the Rio Grande is significantly overallocated and over-appropriated, has resulted in it sometimes running dry before reaching the Colorado – New Mexico border in water-scarce years. And now, a new transbasin export proposal in Colorado’s San Luis Valley threatens to make the situation even worse.

stretches, a pair of National Monuments, and two National Parks – Great Sand Dunes in Colorado and Big Bend in Texas.

It’s a solid 600 miles between rapids before the river reaches its lower Wild & Scenic designation surrounding Big Bend National Park along the Texas border with Mexico. Despite being diverted and depleted for hundreds of miles before reaching El Paso, the river gets replenished by Mexico’s Rio Conchos just upstream from Big Bend’s eastern boundary – enough to feed a 191-mile segment of Wild & Scenic River, established in 1978.

Towering limestone walls stretching up to 1,500 feet in the park’s Santa Elena and Mariscal canyons provide much of the scenery amidst a remote, rugged wilderness that extends far beyond Big Bend’s 118-mile river boundary.

Did You know?

The Rio Grande (“Big River”) was named “El Rio Bravo del Norte,” or “The Fierce River of the North,” by Spanish explorers in the 1500s. It is still known as “Rio Bravo” in Mexico.

Despite its name, the Rio Grande averages only about one-fifth as much water as its neighbor, the Colorado River.

Colorado’s San Luis Valley along the upper Rio Grande is a spring layover for more than 20,000 migrating sandhill cranes and hosts an annual “Crane Fest” at surrounding wildlife refuges.

WHAT STATES DOES THE RIVER CROSS?

New Mexico, Texas

The Backstory

For over a million years, the Rio’s flow was dictated solely by the rhythms of snow and rain, winter and summer. Sometimes, it surged—flooding its banks and ushering sediment downstream. In other years, it whispered its winding way across the landscape. Now, human demands and diversions dictate the course and flow of the river. And, increasingly, a warming climate will establish a rhythm determined by sparse snow and limited runoff.

For people and wildlife that depend on the Rio Grande, this shift in snow and water availability is a cause for serious concern. Less snow means less water for trees, making them more vulnerable to wildfire. It means less water in the river, which means less water in fields and wetlands that dry up and stretches of river where fish can no longer swim.

But climate change isn’t the only threat facing the Rio, its tributaries, and the connected underground sources of water. Since the late 20th Century, developers in Colorado have proposed various plans to pump water out of the aquifers that sit below the Rio Grande for expanding communities on the Colorado Front Range. The latest threat manifests as a developer buying up land and water rights in the northeastern portion of the San Luis Valley, with plans to pump groundwater nearly 200 miles over Poncha Pass in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains to communities north of Colorado Springs.

Existing diversions for municipal and agricultural use already claim a significant portion of the Rio Grande’s average annual flow, and Elephant Butte, the major reservoir south of Albuquerque, only reliably provides irrigation water during a short irrigation season. Increasingly frequent droughts in the face of climate change and growing populations around Albuquerque and El Paso could exacerbate the problem.

The San Luis Valley

In Colorado’s San Luis Valley, the Rio Grande River supports both people and wildlife. The Valley is home to the Rio Grande National Forest, three National Wildlife Refuges and thousands of acres of private lands supporting well-known and lesser-loved wildlife, including the Rio Grande cutthroat trout and the Sandhill Crane. Over 250 unique species of bird are found in the Great Sand Dunes National Park alone. The iconic Sandhill Crane relies on the Valley’s wetlands, stopping here in the spring and fall to rest and gain strength for their journey between New Mexico and the northern United States and Canada.

After winding its way through some of the most productive trout waters in southern Colorado, the Rio Grande tumbles into a cavity of sheer-walled canyons carved from the volcanic rock near northern New Mexico’s Taos Pueblo. The box canyons of the Rio Grande del Norte National Monument, designated in 2013, offer dramatic wilderness and important bird sanctuary surrounding some of the finest whitewater in the West for skilled paddlers, highlighting an outdoor recreational mecca that extends downstream along 74 miles of designated Wild & Scenic river.

It’s a solid 600 miles between rapids before the river reaches its lower Wild & Scenic designation surrounding Big Bend National Park along the Texas border with Mexico. Despite being diverted and depleted for hundreds of miles before reaching El Paso, the river gets replenished by Mexico’s Rio Conchos just upstream from Big Bend’s eastern boundary – enough to feed a 191-mile segment of Wild & Scenic River, established in 1978.

Towering limestone walls stretching up to 1,500 feet in the park’s Santa Elena and Mariscal canyons provide much of the scenery amidst a remote, rugged wilderness that extends far beyond Big Bend’s 118-mile river boundary.

Check out the below resources on the San Luis Valley to gain a better understanding of why protecting and preserving the health of the Rio Grande, the viability of aquifers, and the deep history of the San Luis Valley is as critical for communities that rely directly on the river as it is for the state of Colorado and the Southwest.

The Future

The Rio Grande undoubtedly faces challenges from its headwaters in Colorado to its terminus in the Gulf of Mexico. However, work is being done across its full length to sustain this essential river.

In Colorado, the Rio Grande ties together generations of people and communities across the San Luis Valley. Brought together by shared ethics of caring for land and water, everyone in the San Luis Valley depends deeply on the Rio Grande – for their livelihoods, the rich diversity of wildlife and activities they enjoy, and their connection to the rich history of people who have come before them.

Communities in the San Luis Valley are learning to do more with less, and every drop of water works just a little bit harder. A number of planning initiatives within the Valley have identified multi-benefit projects and solutions to help address the challenges they face. This includes water sharing agreements, restoring riparian areas and instream restoration, implementing nature-based solutions, and upgrading agricultural infrastructure. These strategies will all help restore the river and bolster water flowing underneath the Valley. Learn more about the interdependent nature of the people, wildlife, and the river in our film Through Line. Watch Through Line here.

In New Mexico, water partners and stakeholders are beginning to work with the Bureau of Reclamation on the Rio Grande New Mexico Basin Study. This is a collaborative study that looks to evaluate and develop strategies to help the river and populations who depend upon it adapt to a future with much less water while supporting the basin’s unique human culture and ecosystems. This study will increase preparedness for future changes in water supply and demand and provide a technical basis for water planning and policy decisions throughout the Basin. The Basin Study is anticipated to launch in early 2022.

Communities throughout the Rio Grande Basin understand the challenges facing their sources of water. A balanced approach to water management and investments in activities to improve the resilience of the river and the communities that depend on it is needed if the once mighty Rio Grande hopes to recover.

San Joaquin River

Most people think of agriculture when they think of the San Joaquin River. They don’t consider king salmon swimming upstream through cool waters to spawn on the high slopes of the southern Sierra Nevada, or vast wetlands supporting millions of waterfowl and even elk herds. But they should.

The hardest working river in California originates from headwaters that include Yosemite and Kings Canyon National Parks and the Ansel Adams Wilderness. Principal tributaries like the Tuolumne and Merced provide inspiring reminders of what the 366-mile river coursing through the fertile San Joaquin Valley south of Sacramento once offered, and may yet offer again.

The river meets the other half of the state’s largest watershed at the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta where the combined rivers flow west through the Carquinez Strait into San Francisco Bay.

An abundance of wildlife depends on this river, including a significant portion of the Pacific salmon fishery that once flocked upstream by the millions. The breadth of the watershed supports a recreation industry that generates billions of dollars in economic activity and includes world-class whitewater paddling, salmon and trout fishing, and waterfowl hunting.

They also support some of the most productive and profitable agriculture in the world, irrigating more than two million acres of arid land. The rivers generate enough hydropower for more than 4 million homes, and provide drinking water to over 25 million people, including the cities of San Francisco and Los Angeles.

Did You know?

Before agricultural development of its valley, the San Joaquin was navigable by steamboats as far upstream as Fresno.

At 31,800 square miles, the San Joaquin watershed is the largest single river basin entirely in California, comparable in size to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan.

The Sacramento, when combined with the Pit, is one of the longest rivers in the United States entirely within one state. Only the Kuskokwim in Alaska and the Trinity in Texas are longer.

Groundwater withdrawal has led to land subsidence of more than 28 feet in the San Joaquin Valley near Mendota.

The Sacramento supports nearly 60 species of fish and 218 types of birds. Native bird populations on the river have declined steadily since the 19th century.

The Backstory

Humans have not treated these rivers well through the years. More than a century of managing them for agriculture, hydropower, and flood control has taken its toll. The health of the San Joaquin River has suffered the impacts of hundreds of dams, levees stretching thousands of miles, and countless water diversions. More than 95 percent of floodplain and freshwater tidal marsh habitat has been converted to development or agriculture. Once-iconic salmon runs teeter on the brink of extinction.

The problems are so acute that American Rivers named the San Joaquin River one of America’s Most Endangered Rivers® in 2014. In 2016, it rose to the No. 2 position on the list.

Man’s manipulation has severely hurt river habitat and opportunities for recreation and community access. More than 100 miles of the San Joaquin’s main stem have been dry for over 50 years, and water diversions along the tributaries take more than 70 percent of the natural flow. Before irrigation development, the river and its tributaries once supported the third-largest run of Pacific salmon in California, measuring more than 200,000. Today, the few remaining fish have nowhere to go.

People are at risk as well. Outdated approaches to water management have made communities vulnerable to increasingly frequent and severe droughts and floods.

The Future

There is hope on the horizon, however. California has never experienced a greater opportunity to address these threats and American Rivers is already hard at work.

There are many reasons for optimism. Voters recently passed a $7 billion “Water Bond” designed to jumpstart critical improvements to fisheries, habitat, flood safety, and water quality. The State Water Board is developing a new plan to meet water quality standards and protect the public values provided by the San Joaquin, Sacramento, and Delta watershed. More than two dozen dams must get new operating licenses that better protect rivers, native fish and water quality. The Central Valley Flood Protection Plan will be updated in 2017.

All that adds up to more water in the rivers. The Water Board must act this year to increase flows in the San Joaquin so that the watershed is healthy enough to support fish and wildlife, sustainable agriculture, and resilient communities for generations to come. In order to comply with state and federal laws, the Board must require dam owners to release more water to the river in a manner that mimics the natural flow regime.

Meanwhile, American Rivers has embarked on multi-benefit projects on the San Joaquin designed to enhance flood safety and restore salmon-rearing habitat by reconnecting the floodplain. Projects designed to improve water quality, increase water quantity, and improve quality of life by establishing the river as a more vibrant community asset are also underway.

While drought and climate change are affecting water patterns, they are also teaching Californians to adapt, improve groundwater storage and figure out ways to make a finite resource stretch farther. The San Joaquin River and the communities that depend on them are currently being acted upon by a confluence of forces that will create opportunities for historic success, or epic failure.

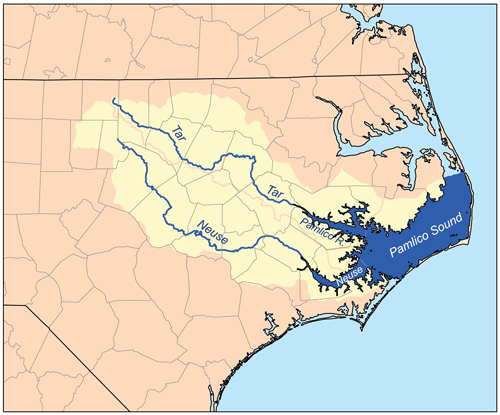

Neuse River

RIVER OF PEACE

The Neuse—derived from the Native American Neusiok tribe and translating to “peace”—is an excellent river to experience. Linking North Carolina’s original capital city of New Bern to its current capital of Raleigh, the Neuse River serves as a 250-mile connection between past and future—and the Piedmont and Pamlico Sound. A lot can happen over that kind of distance.

The action gets underway at the headwaters, where the dynamic community of Raleigh-Durham remains one of the fastest growing regions in the nation. Roughly 2.5 million people live within the river basin, most of them on this upper end. The Flat and Eno Rivers merge to form the Neuse River under Falls Lake Reservoir, Raleigh’s primary water supply, which spans more than 12,000 acres and also provides some structural flood control in the basin. The removal of the antiquated Milburnie Dam in the fall of 2017 allowed the unbridled river to glide from Falls Lake Reservoir all the way to the Atlantic, making it one of the longest free-flowing rivers in the Southeast.

The Neuse River Greenway Trail winds through wetlands on a boardwalk and courses alongside the river as Raleigh’s contribution to the state’s Mountains-to-Sea Trail that runs from the Great Smoky Mountains to the Outer Banks. In 2020 the Neuse River Blueway was launched creating a interconnected network of paddle and walking trails. About halfway between Raleigh and the river mouth, the Cliffs of the Neuse rise up as an impressive 100-foot canyon within the coastal plain at Seven Springs. Hiking trails at the surrounding state park explore the riverside habitats and their mature forests and lead to some quiet fishing spots along the waterway.

Did You know?

The Neuse is the longest river contained entirely within North Carolina.

The Neuse is considered one of the widest rivers in the U.S. Six nautical miles across at its widest point, it averages more than three miles in width between the Intracoastal Waterway and New Bern.

Established at the river mouth in 1710, New Bern is the first capitol of the state of North Carolina.

At an estimated 2 million years old, the Neuse is one of the oldest rivers in the U.S. Archeological evidence shows that humans settled around the Neuse some 14,000 years ago.

What states does the river cross?

North Carolina

The plot thickens near the mouth of the Neuse, where the river changes to slow-moving estuary habitat before joining the Tar and Pamlico Rivers in Pamlico Sound. Easily explored by kayak, canoe or SUP, the estuary is home to a wide variety of coastal game fish as well as birds, oysters, and countless other species. Dolphins and alligators are seen regularly in the estuary, and sharks and manatees occasionally appear as far upriver as New Bern, about 35 miles from the Atlantic.

The Neuse has an excellent striper run, and is home to several species of fish that split their time between the ocean and freshwater, like shad, herring, and American eel. Many endangered species including the Carolina madtom (a freshwater catfish), Tar River spinymussel, piping plover, dwarf wedge mussel, and loggerhead turtle remain in the Neuse River basin. The Neuse is also home to vital populations of blue crab and oysters.

The Backstory

The Neuse has suffered from municipal and agricultural pollution issues for decades now, prompting its listing as one of America’s Most Endangered Rivers® in 2007 after multiple nominations. Currently, the river is plagued by excessive nitrogen and phosphorous from agricultural-wastewater and polluted-stormwater runoff from urbanized and rural areas. The impacts of climate change have also led to extreme flooding events across the watershed.

On the main stem of the river, recurring algal blooms continue to show that the controls designed to reduce excessive pollution are not meeting the needs of a balanced ecosystem. The algae can produce toxins leading to some of the largest fish kills in the nation. An estimated 150,000 fish died as a result of a low oxygen “dead zone” in the Neuse River estuary over 10 days in July, 2015.

Falls Lake Reservoir has a major impact on the basin. While it has been very effective at flood control, it also separates the Neuse River from its floodplain, eliminating critical habitat, reducing water quality, and impairing the river’s ability to recover from increasing droughts and floods.

In the headwaters, the amount of water flowing in the tributaries to Falls Lake Reservoir has been declining for years due to development and land use conversion, droughts, and increased water demands. Only a small amount of the reservoir is dedicated to water supply, and there is a growing awareness that Raleigh’s reliance on Falls Lake Reservoir for a clean and abundant water supply into the future is in jeopardy. Raleigh Metro is already home to 1.3 million people and growing at a rate of 2.2 percent a year. North Carolina is expected to add more than 3 million people by 2029.

The reservoir is also impaired due to excessive nitrogen and phosphorous from failing wastewater treatment plants upstream and stormwater runoff from the surrounding urbanized and rural areas in Durham, Orange, Granville, and Person County. Many of the streams flowing into the reservoir have been impacted as well and need restoration to allow them to be an asset for the communities around them.

The Future

The Neuse’s free-flowing nature from Raleigh to the Atlantic provides great opportunities for communities around the river to embrace it as a recreational and economic resource. Of the 3.5 million acres that comprise the Neuse Basin, 48,000 acres are state parks, 110,000 acres are game lands held by the Wildlife Resources Commission, and 58,000 acres are National Forest.

But the issues surrounding water quality and the water supply in the Neuse need to be solved together. The Neuse River watershed is at the center of a tangle of federal, state, and local regulations and incentives, each designed to address a specific issue without taking into account the system as a whole and the interconnections that exist between having clean water and ensuring water supplies for people and nature. A new water management system needs to be developed that reduces the silos of management existing today and relies on natural infrastructure to restore the balance of the watershed. That involves updating the management of Falls Lake Reservoir in order to meet the needs of the growing population and working to restore the floodplain to reduce downstream pollution from agricultural operations.

The basin is losing crucial elements of its natural systems—healthy streams, wetlands, forests, and floodplains—that filter clean water and provide flood protection. Major developments proposed to accommodate the projected population increase of a million new residents in the Neuse River basin will magnify the issue if steps are not taken to balance the system. American Rivers’ long-term goal is to create a comprehensive water management system within the Neuse basin that provides reliable, sustainable clean-water supplies and recreational opportunities for growing urban and rural communities while protecting and restoring the ecology of the basin.

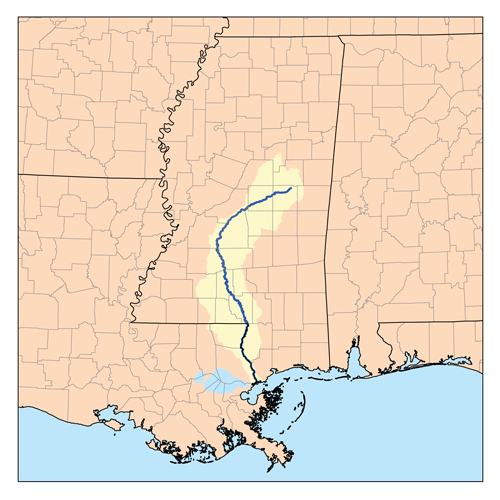

Pearl River

The Pearl River ranks 4th in freshwater discharge among the rivers draining into the Gulf of Mexico. This river provides drinking water to hundreds of thousands of residents in Metropolitan Jackson, Mississippi. In addition, estuaries in Louisiana and Mississippi at the Pearl’s mouth are highly influenced by the river’s freshwater flows. Productive oyster reefs in the Mississippi Sound and in Louisiana’s Biloxi marshes need the salinity moderation the river provides. The marshes and oyster reefs in these areas took a direct hit from Hurricane Katrina in 2005, sustaining considerable damage that was later compounded by the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010. Oyster reef restoration projects near the mouth of the Pearl River are ongoing in both states.

The Pearl River is home to 110 species, including two federally-threatened species (Gulf sturgeon and the endemic ringed sawback turtle) and other species of special concern (pearl darter and frecklebelly madtom). This project would also impact floodplain forest bottomlands along the Pearl River in Jackson, including part of LeFleur’s Bluff State Park, which is designated as an Important Bird Area by Audubon Mississippi.

Threats to This River

The Pearl River is threatened by a new dam that would create another impoundment on its main channel. The Ross Barnett Dam, built in 1963, created a 32,000 acre reservoir for drinking water and recreation north of Jackson, Mississippi. Operation of that dam has changed downstream reaches in two ways. First, banks are unstable, often collapse, and contribute more sediment than the lower river can move efficiently. Second, dam operation coupled with evaporation effects cause water deficits downstream in Louisiana’s Honey Island Swamp and at the coast. Furthermore, water releases at the Barnett Dam during storms or hurricanes have, at times, contributed to coastal storm surges, exacerbating flooding along the lower Pearl River. Sea level rise on the coast, coupled with low flows, already cause saltwater intrusion in the lower basin’s cypress swamps. Climate change will magnify these impacts.

This year, the Rankin-Hinds Pearl River Flood and Drainage Control District is sponsoring an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) and feasibility study for a new dam, impounding a new reservoir 9 miles downstream of the existing Barnett Dam. This proposed artificial lake is a dredging project to widen, deepen, and straighten 7 miles of the river and place a low-head dam or weir at the downstream end. This project is being advertised as a flood control strategy to decrease flood elevation in urban Jackson. While the flood control features of this lake design are unproven, areas immediately downstream of this new dam will likely feel the negative effects of faster flows and riverside habitat in a state park will be submerged. Ultimately, levees will need to be improved, and more bank collapse, sedimentation, erosion, and rapid evaporation are certain to follow. Further changes to the amount and timing of freshwater discharge threaten coastal fisheries, especially the oyster industry. The Pearl River needs comprehensive restoration and natural flood protection strategies, not more outdated dam projects.

One Louisiana Parish and the Mississippi Commission on Marine Resources have passed resolutions in opposition to the project. Additionally, the Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Agency and the Louisiana Wildlife and Fisheries Department are both on record outlining serious concerns about the project.

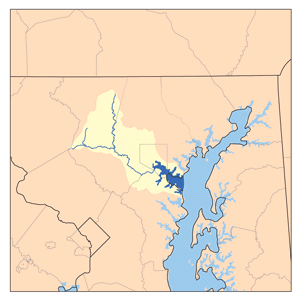

Potomac River

America’s River

George Washington could have built his home anywhere on the Eastern Seaboard. He chose the Potomac River, forever identifying it as the “Nation’s River.”

But even more significant than Washington’s riverside estate at Mt. Vernon and the Federal City bearing his name just upstream, the Potomac’s first calling is its service as the southern headwaters of the Chesapeake Bay. The cultural and historic lifeblood of our nation’s capital remains a living, pulsing force providing sustenance and vitality to the most important estuary in the East.

Only the Susquehanna River emptying into the Chesapeake’s northernmost point at Havre de Grace, MD, qualifies as a larger tributary than the Potomac. Originating in the Allegheny Mountains of West Virginia and drawing from the hills of Virginia and Maryland, which are collectively recognized as the Potomac River Highlands, the river offers a diversity of culture, history, and wildlife as it channels the border between those states and Washington, DC, on its 380-mile run to the Tidewater at Point Lookout, MD.

Along the way, it picks up water from key tributaries including the Anacostia, Shenandoah, and Monocacy rivers, and connects people to nature. Its watershed of 14,670 square miles is nearly 60 percent forest, qualifying it as one of the most forested in the country. It provides critical habitat for wildlife and multiple species of fish while offering the nation’s capital a place to play.

Fishing, paddling, hiking, boating, wildlife watching and riverside sightseeing are just a few of the popular pastimes for the millions who visit the vast river basin. More than four million people come to the historic Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historic Park annually, with the thundering Great Falls of the Potomac Gorge as one of the park’s biggest draws. From fly fishing shops and whitewater kayakers to commercial fishermen, marinas, and restaurants, everyone benefits from access to clean river water.

President Bill Clinton designated the Potomac as an American Heritage River in 1998, which, for five years, allowed communities along the rivers to access federal resources to help revitalize their rivers, riverfronts, and local economies.

Did You know?

The largest flow ever recorded on the Potomac at Washington, DC, was 425,000 cubic feet per second in March, 1936. The lowest flow ever recorded at the same location was 600 cfs in September, 1966.

After assassinating President Lincoln in April of 1865, John Wilkes Booth attempted to escape by crossing the Potomac by boat. Due to poor navigation, he landed downstream in Blossom Point, MD.

In 1930, Congress deemed the Great Falls area of the river a national park and the National Park Service took over its operations in 1966.

President Bill Clinton designated the Potomac as an American Heritage River in 1998.

What states does the river cross?

Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Washington DC, West Virginia

The Backstory

President Lyndon B. Johnson had a different perspective back in 1965, when he called the Potomac “a national disgrace” because of the polluted water that filled the channel. Wetlands and streams had been bulldozed, filled in, and destroyed. The river that provides 90 percent of the drinking water to the Washington, DC, metro area was overrun with algae and trash.

The headwaters of the river may have suffered even more. Originating in the heart of America’s coal country, the fragile streams making their way east to the Atlantic fell as casualties to the impacts of mining development and deforestation along their way to the farmlands of the mid-Atlantic, where they were loaded with nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment. Urban runoff from streets and parking lots, and other contaminants in the water, like pharmaceuticals, further contributed to the river’s deterioration as it wound its way to the bay.

Native fish, including bass, muskellunge, pike, walleye, shad, and white perch all suffered as a result. Meanwhile, the invasive northern snakehead made its way into the river basin along with predatory blue catfish, putting native species at risk.

The Future

The Clean Water Act of 1972 started the resurgence of the Potomac and rivers across the country. Thanks to the safeguards of the Clean Water Act, the Potomac is significantly healthier than before and has become a magnet for recreation and an asset to nearby residents. After decades of decline, the Potomac River is on its way to recovery.

The Potomac Conservancy has given the river increasingly higher marks since 2011, saying it’s the only major Chesapeake Bay tributary to achieve short- and long-term nutrient reductions in its headwaters. The top three pollutants in the Potomac—nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment—are on the decline, and shad, white perch, and other common game fish are making a comeback. Protections for more than 25 percent of the region’s land is providing tributaries with clean, healthy water and more people than ever are experiencing the river through fishing, water-access trails, and state parks.

The downside is that polluted urban runoff remains as the only growing source of pollution in the Potomac and Chesapeake Bay. Poorly-planned development in once-rural areas is paving over river-friendly forests. Underwater grasses and water clarity in the Potomac have been slow to recover.

Still, progress is being made for this lifeline to the Chesapeake Bay. And as our elected officials gaze upon the Potomac there is hope that soon it will re-achieve the standards of excellence worthy of our Nation’s River.

Rogue and Smith Rivers

Wild and Scenic. Rogue and Smith. There was never any question.

Southwest Oregon’s Rogue River is an icon among Western waterways. As one of eight charter members of the Wild and Scenic Rivers System in 1968, the 200-mile Rogue flows from the Cascade Range near Crater Lake westward to the Pacific, offering inspiring beauty, world-class recreation and abundant wildlife virtually the entire way.

Did You know?

California’s Smith River contains a 325-mile segment designated as Wild and Scenic, the longest in the U.S.

The federally-managed public lands in the Illinois Valley have the highest concentration of rare, threatened, endangered, or sensitive plants in the world.

The 345-foot-high William L. Jess Dam blocks the Rogue River 157 miles from its mouth, preventing salmon migration above that point.

WHAT STATES DOES THE RIVER CROSS?

California, Oregon

The deep green pools, sparkling waterfalls, and playful whitewater of the Rogue’s lush upper canyons have made it the most famous river trip in the Pacific Northwest. And an average of 100,000 salmon and steelhead returning to the river each year qualify the lower basin as one of the most productive fish runs on the entire West Coast (second only to the Columbia). Its largest tributary, the Illinois River, is the wild salmon and steelhead refuge for the Rogue Basin and home to the highest concentration of rare plants in Oregon.

Just to the south, the emerald-green Smith River is a free-flowing gem tumbling down the slopes of the Siskiyou Mountains in the far northwestern corner of California. As the last remaining free-flowing river system in the state, it holds the California state record for steelhead (27 pounds) and produces many of the biggest salmon outside of Alaska. Breathtaking scenery includes one of the state’s premier stands of old-growth redwoods in Jedediah Smith State Park.

Much of the Smith watershed has been protected by a 305,000-acre National Recreation Area that forms the northern border to Redwood National and State Parks. Together with the Rogue and Illinois, the threesome establish the highest concentration of Wild and Scenic Rivers in the contiguous United States. The 325-mile segment of the Smith constitutes the longest Wild and Scenic River in the U.S.

The Backstory

This treasure trove of outstanding scenery, inviting whitewater, ancient forests, rich biodiversity, and thriving fisheries has come under attack in recent years as mining companies have submitted plans strip mine and drill on dozens of sites previously recommended as federal Wilderness or Roadless Areas.

The Rogue and Smith rivers were listed among America’s Most Endangered Rivers® in 2015 after nickel strip mining was proposed in the headwaters of Hunter Creek and the Pistol River, along the Wild Rivers Coast between the Rogue and Smith river watersheds. Hunter Creek and North Fork Pistol River are known for their strong native salmon and steelhead runs, designated Botanical Areas, and two BLM Areas of Critical Environmental Concern. The collection of rivers is prized by boaters, botanists, anglers, and local communities.

The Smith River watershed faces the added threat of a foreign-owned mining company’s ongoing attempt to conduct exploratory drilling at 59 sites along important tributaries across approximately 3,000 acres of the South Kalmiopsis Roadless Area. The Bush Administration recommended a portion of this watershed for Wilderness designation.

The Future

Mining for metals is recognized by the EPA as the biggest toxic polluter in the U.S. and the Forest Service has already concluded that this type of mining would have drastic and irreversible impacts in Rough and Ready Creek, one of the threatened tributaries in the Rogue watershed.

Salmon, steelhead, cutthroat, and world-renowned biologically diverse plant species are not the only things that would suffer the devastation of this precious wild area. Local communities in Southwestern Oregon and Northern California also depend on these rivers for clean drinking water, recreational and commercial fishing, and a recreational economy that generates hundreds of thousands of dollars each year.

Prompted by the threat of mining, Senators Ron Wyden and Jeff Merkley (OR) and Representative Peter DeFazio (OR) and Jared Huffman (CA) have introduced the Southwestern Oregon Watershed and Salmon Protection Act that would permanently protect these watersheds from new mining activity. Federal agencies stepped up with a temporary ban and a public process to consider a five-year ban on new mining while Congress considers the introduced legislation. The ban would prevent new mining claims and require proposed mines to meet a rigorous review process.

Immediate closure of the area to mining is the most effective way to help prevent the development of nickel strip mines from turning the pristine headwaters of the highest concentration of wild rivers in the country into an industrial mining zone. The U.S. Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, and Department of Interior must withdraw this area from mining immediately to protect this wild treasure.

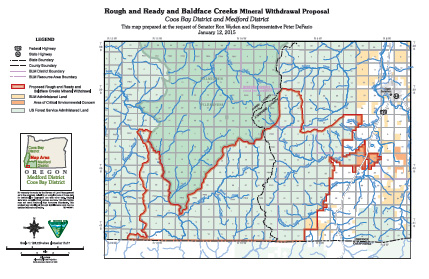

Rough & Ready and Baldface Creeks

Rough & Ready and Baldface Creeks, tributaries of the Wild and Scenic Illinois and North Fork Smith rivers, flow clean and clear through some of the wildest country in the West.

These eligible Wild and Scenic Rivers are celebrated by wildflower enthusiasts and hikers. Unfortunately, nickel mines threaten to destroy these unique, wild streams. Members of the Oregon Congressional delegation previously asked the Obama Administration to withdraw the area from mining, but the Administration did not act.

Congress and the Interior and Agriculture Secretaries must now permanently protect the natural treasures of Rough & Ready and Baldface Creeks from mining before their clean water, fish and wildlife, and wild character are irreparably harmed.

Threat to This River

At Rough & Ready Creek, a recently formed mining company has located new claims and submitted a new mining plan to USFS. It includes mining lands recommended as Wilderness, miles of road construction in the Rough & Ready Creek Botanical Area and South Kalmiopsis Roadless Area, and a smelter facility on the Rough & Ready Creek Area of Critical Environmental Concern.

At Baldface Creek, a foreign-owned mining company has submitted a plan to conduct exploratory drilling at 59 sites in the Baldface Creek/North Fork Smith watershed, across approximately 2,000 acres of the South Kalmiopsis Roadless Area. The information gathered will be used to advance mine development. Baldface Creek’s watershed was recommended as Wilderness by the Bush Administration.

The Environmental Protection Agency identified metal mining as the largest toxic polluter in the U.S. Strip mining, road construction, and metal processing would devastate this fragile, precious wild area. If one mine starts operating, thousands of acres of other nickel claims could be developed on nearby federal public lands— impacting designated and eligible Wild and Scenic Rivers and turning one of North America’s most important rare plant centers and clean water supplies into an industrial wasteland. The Forest Service already concluded that this type of mining would have drastic and irreversible impacts at Rough & Ready Creek. Dangers include high chromium content smelter waste, naturally occurring asbestos, air and water pollution, and impacts to a world-class salmon and steelhead river.

Members of Oregon’s Congressional delegation have repeatedly asked the Obama Administration to help them protect these Oregon treasures by withdrawing the federal lands in the Rough & Ready and Baldface Creek area from the 1872 Mining Law. Despite the extremely high scientific, social, and ecological values at risk, the area remains open to destructive mining and acquisition by mining companies under this unjust antiquated law.

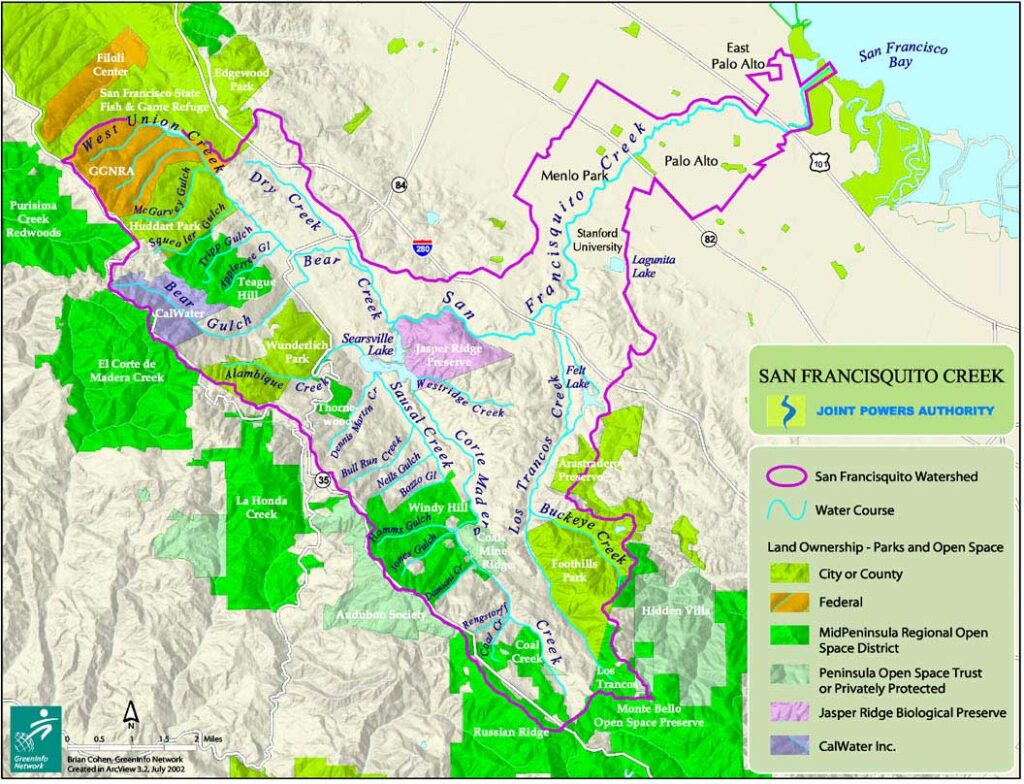

San Francisquito Creek

Urban Oasis

Nearly hidden among a kaleidoscopic community of some four million Californians, San Francisquito Creek has managed to remain a remarkably undeveloped riparian oasis beneath scattered oak and redwood. The small stream that managed to escape urbanization as the boundary between the cities of Palo Alto, East Palo Alto and Menlo Park offers a sliver of hope for the most viable remaining native steelhead population in the South San Francisco Bay.

Fueled by winter rains and year-round springs, the creek’s 45 square mile watershed gathers dozens of small tributaries draining the Eastern Slope of the Santa Cruz Mountains. The short San Francisquito main stem, formed at the confluence of Bear Creek and Corte Madera Creek, flows for 12 miles east through Stanford University before meeting the southern portion of San Francisco Bay, the largest estuary on the West Coast.

Disagreements between bordering counties managed to preserve San Franciscquito as one of the only San Francisco Bay streams that is not confined to a concrete channel. Yet it could not prevent the construction of 65-foot Searsville Dam, the only thing standing between wild steelhead and access to 20 miles of native habitat upstream.

Evidence suggests coho salmon likely inhabited the stream at one time as well, alongside a host of native fish ranging from the Sacramento sucker, California roach, and three-spined stickleback to the no-longer-present Sacramento perch, squawfish, and seldom seen prickly sculpin. On the river’s edge, gray foxes have been documented near the mouth of San Francisquito Creek and on the Palo Alto Golf Course.

Did You know?

The tree from which Palo Alto takes its name, El Palo Alto, stands on the banks of San Francisquito Creek.

David Starr Jordan, the first President of Stanford University, included a rendering of a “sea-run rainbow trout from San Francisquito Creek” in the Pacific Monthly (now known as Sunset magazine) in 1906.

Originally called the Arroyo de San Francisco, San Francisquito Creek forms the boundary between San Mateo and Santa Clara counties, reflecting the original boundary between the Spanish Missions at San Francisco and Santa Clara.

The Backstory

Built more than 120 years ago to provide drinking water for Stanford University students, Stanford-owned Searsville Dam never served that purpose and is no longer needed for the school’s non-potable water supply. Yet it continues to cause significant harm to San Francisquito Creek and the fish and wildlife that depend on it.

Steelhead trout were documented in the watershed as far back as the 1800s. The fish still migrate from the bay up to the barricade, but Searsville Dam serves as a complete barrier to their natal streams above. The dam blocks access to 20 miles of steelhead habitat upstream and reduces flows downstream, often blocking all flows in summer. It also drowned the confluence of five creeks and extensive wetlands, trading important riparian habitat for several species of birds, frogs, turtles, salamanders and other wildlife for a sediment-filled slackwater reservoir.

The reservoir is bad for native species because it has lower water oxygen levels, higher water temperatures, supports invasive species and algae blooms, and encourages the loss of water through evaporation. More than 90 percent of Searsville Reservoir is already filled in with sediment, eliminating its usefulness as a water storage facility. Unless Stanford takes action soon, the reservoir will fill in completely in coming years, posing safety risks to several nearby communities.

The Future

Despite an internal advisory committee at Stanford recommending in 2007 that Searsville Dam remain and the lake be dredged to maintain open water, the university is currently seeking additional analysis and a decision on dam removal is expected sometime in the next year.

But the writing’s on the wall. Already, San Francisquito Creek hosts the most viable remaining native steelhead population in the South San Francisco Bay, and the Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration named San Francisquito an anchor watershed for the recovery of wild steelhead trout in the bay. In 2014, a systematic study of more than 1,400 dams in California identified Searsville Dam as a high-priority removal candidate to improve environmental flows for native fish conservation.

It is time for Stanford to remove this obsolete dam to restore the health of the creek and secure the safety of its communities.

Niobrara River

The Niobrara River is an oasis for paddlers, anglers, and wildlife. A major tributary of the Missouri River, the lower portion of the Niobrara is protected as a federal Wild and Scenic River.

The Lower Niobrara is increasingly threatened by too much sediment backing up in the upper reaches of Lewis and Clark Lake behind the Missouri River’s Gavins Point Dam.

The sediment is raising the level of the Niobrara and threatening local communities with flooding. To safeguard the Wild and Scenic Niobrara and its communities, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers must improve sediment management within the Missouri River system and must prioritize funding for this critical issue in their budget.

Threats to This River

Dams and other flood control structures built in the mid-1900’s on the Missouri River have caused sediment to accumulate in the reservoir system. When sediment builds up on the riverbed it raises river levels, creating flooding issues for tributaries like the Niobrara River. At one time, most of that sediment was flushed out of the system to the Mississippi River where it helped build coastal wetlands along the Louisiana Delta— keeping saltwater intrusion at bay. Now, reservoirs behind dams act as sediment traps, slowing the flow of the river and allowing sediment to settle, accumulate, and consequently deplete reservoir flood storage capacity. At the same time, water management for navigation using water released from dams has caused lowering of the riverbed below Gavins Point Dam. Without sediment replenishment, it takes more water to serve downstream authorized purposes.

The sediment build-up is so extreme at the confluence of the Niobrara and Missouri Rivers that the overall level of the local water table has increased substantially. This leads to flooded cropland and basements, and greatly impacts boating and other recreation. Flooding due to sedimentation forced relocation of the Village of Niobrara in 1973. Downstream from the confluence, Lewis and Clark Lake is expected to lose 50 percent of its water storage capacity by 2045 due to sediment accumulation in the reservoir— to date, it has already lost 30 percent of capacity.

As the sediment builds within the system, the Lower Niobrara is slowly losing the seeps, springs, riparian forests, prairies, and canyons that characterize this Wild and Scenic River. Only a few of the great cottonwood trees in the confluence area have survived the recent sustained high waters. The USACE has purchased thousands of acres of riverside land to limit future liability, but this is not the long-term answer. The underlying sediment problem must be addressed now to secure a future for this Midwestern treasure.

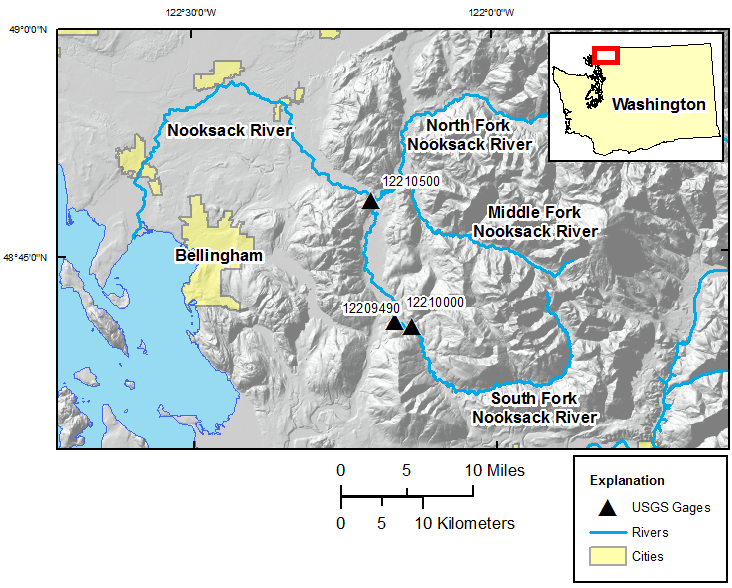

Nooksack River

The only thing it lacks is the Wild and Scenic label

The Nooksack River puts the great in the Great Northwest. Its spectacular North Fork is the northernmost river in Washington, running wild with icy glacial snowmelt from the snowfields of 10,778-foot Mount Baker and 9,127-foot Mount Shuksan in North Cascades National Park, before being joined by the Middle and South forks as it weaves through forests and farmlands on its way to the Salish Sea in Puget Sound north of Bellingham.

With volcanic Mt. Baker and the Twin Sisters Range of the jagged North Cascades dominating the surrounding landscape, the upper river was shaped as much by fire as ice through the millennia, creating a one-of-a-kind watershed treasured for its vast array of scenery and recreation. Whether it’s whitewater paddling beneath (or skiing atop) towering snowcapped summits; fishing in ancient forests for five species of native salmon, steelhead, resident rainbows, and cutthroat trout; hiking past waterfalls on the nearby network of trails; or scoping out abundant bald eagles, black bears, mountain goats, elk, spotted owls and even the rare bull trout, the Nooksack does not disappoint.

If there is a downside, it is found in lack of permanent protection for this great Northwestern treasure. Such high-quality habitat is increasingly rare and valued by millions for the clean water it provides for drinking, farming, outdoor recreation, and tourism. A cultural mix of native tribes, heritage farm towns, burgeoning New West communities, and the wildlife surrounding them all depend upon an unspoiled Nooksack River connecting glacial headwaters with the sea. Yet the majority of this vital river system remains deprived of even the most fundamental protection.

Did You know?

Mt. Baker (feeding the Nooksack River) is one of the snowiest places in the world. In 1999, Mt. Baker Ski Area set the world record for recorded snowfall in a single season—1,140 inches.

The endangered Marbled Murrelet is a small Pacific seabird that nests in old growth forests surrounding the Nooksack but has declined in numbers since humans began logging in the region.

The Nooksack Indian Reservation is in Whatcom County Washington. Whatcom was the name of a Nooksack chief and means “noisy water” in the Nooksack language.

What states does the river cross?

Washington

Other Resources

Check out these other resources to learn more about the river:

Nooksack Wild and Scenic Campaign website

The Backstory

The Nooksack Wild and Scenic effort is about conserving the ecological and recreational values of this magnificent river system. A diverse array of interested citizens, business owners, and organizations has worked for years to build widespread public support for Wild and Scenic River legislation designed to permanently protect over 100 river miles and 32,000 acres of riverside habitat in the upper Nooksack basin, including portions of all three forks and eight tributary streams.

Like much of the Northwest, some 40 hydroelectric dams have been proposed for various sites on the Nooksack since the 1970s, the legacy of logging impact remains along portions of the river, and a diversion dam on the Middle Fork has blocked passage of salmon and steelhead for nearly 70 years. Tremendous efforts are underway to restore the ecological health and improve the habitat of the Nooksack River and protecting the headwaters as Wild and Scenic would help protect these investments in restoration.

The Future

Keeping the Nooksack great remains a top priority in the region. Wild and Scenic designation would ensure that the river’s “Outstandingly Remarkable Values” are protected and enhanced in the future and prevent any new dams or other projects that would degrade the river’s natural character and healthy flows. The Nooksack Wild and Scenic campaign is working toward drafting legislation by 2017.

Recreational access around the river corridor is also a major concern and American Rivers is working with a variety of partners to implement recommendations in the Upper Nooksack River Recreation Plan, a planning effort spearheaded by American Rivers intended to improve access and guide recreational use in the region for the next 10-15 years. American Rivers is also an advisory committee member on Washington Department of Natural Resource’s new recreation planning effort called the Baker to Bellingham Recreation Plan.

In late 2020, American Rivers worked with several partners including Washington State Department of Natural Resources, Whatcom Land Trust, the Nooksack Tribe, American Whitewater, and others, with technical assistance from the National Parks Service, to finalize a plan for the Maple Creek Public River Access and Restoration Site. This site was identified in the Upper Nooksack River Recreation Plan as an ideal location for safe public recreation access along the North Fork Nooksack River, while also allowing natural resource managers to protect, restore, and enhance the adjacent riparian forest and natural river systems.

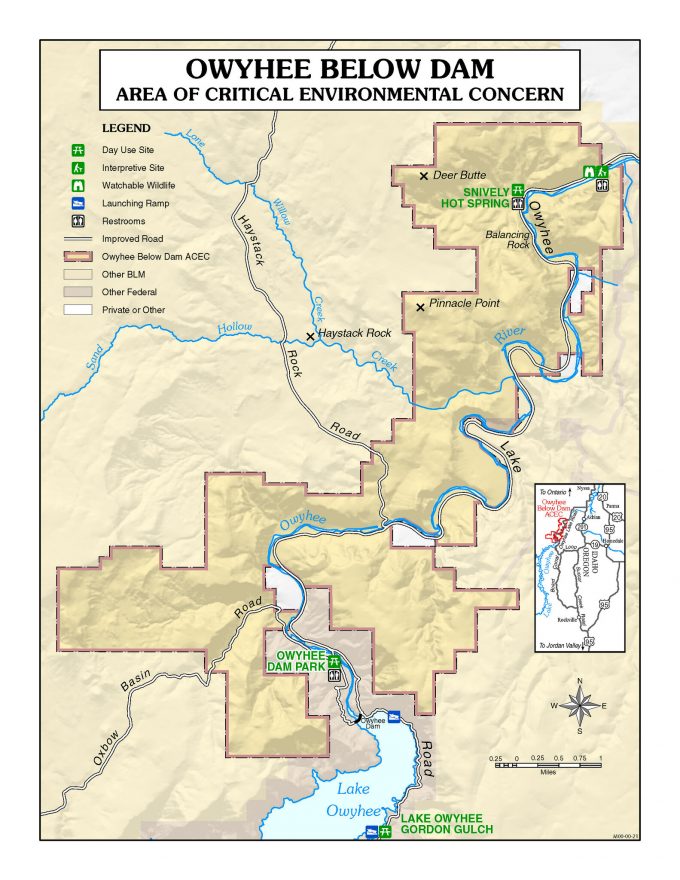

Owyhee River

The Owyhee Canyonlands is a national treasure and a crown jewel of the great state of Oregon. It’s one of the most remote, wild and untouched places in the American West. The Owyhee is irreplaceable—and represents one of the largest conservation opportunities remaining in the continental United States.

Reaching more than 2 million acres in the eastern stretches of Oregon, the opportunities for solitude, adventurous recreation, backcountry experiences in the Owyhee are unparalleled. However remote, the Owyhee is bursting with life. From time immemorial the Native American tribes of the Upper Snake River have called this area home, and the vast tracts of public lands are leased to support traditional ranching opportunities and are increasingly attracting tourism to the region. Rugged red-rock canyons, carved by desert rivers and blue-ribbon trout streams, the Owyhee’s diverse wild lands and waters is also home to more than 200 species, including golden eagles, pronghorn antelope, elk, the imperiled Greater sage-grouse and the largest herd of California bighorn sheep in the nation.

However, the landscape is threatened by unmanaged recreational use, desecration of tribal sacred sites, wildfires, invasive species and unsustainable grazing practices. While remoteness has long safeguarded the Owyhee, development pressure — including mining and oil and gas development — is clawing at its edges. Fortunately, local advocates had the foresight to work together to speak up for this wild place and all it stands for. And statewide and local support continues to grow.

Starting in 2018, at the invitation of Oregon Senator Ron Wyden, American Rivers worked with the Owyhee Basin Stewardship Council, a locally based ranching organization, the Burns Paiute Tribe, the Upper Snake River Foundation and our conservation partners to establish a meaningful collaboration between tribal nations and the ranching community to protect the Owyhee Canyonlands. The objectives of the collaborative are to develop strategies for invasive species encroachment, address fire risk and secure protections for more than 1.2 million acres of public land and 15 miles of the Owyhee River as Wild and Scenic in Malheur County.

Did You know?

Indigenous peoples have lived in this landscape since time immemorial, and the Owyhee is the homelands to regional tribes, including the Burns Paiute, Fort McDermitt Paiute-Shoshone, Shoshone-Bannock, Shoshone-Paiute, Cayuse, Umatilla and Walla Walla.

Spanning three states, the vast Owyhee watershed includes more than 500 miles of rivers, streams and springs that support fish, wildlife and people.

In Idaho and Oregon’s portion of the Owyhee river system, there are more than 300 miles of Wild & Scenic River and many more that are worthy of protection.

Prior to the dam-building era of the 1930s, salmon historically made their way from Nevada to the Pacific Ocean and back via the Owyhee, Snake, and Columbia Rivers.

The Owyhee Canyonlands is one of the best places to view the night sky and the Milky Way and in the coming decade with development scientists say it may become one of the only places to view these starry wonders in the lower 48.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has pinpointed the Owyhee Canyonlands as one of six areas in the nation critical to the Greater sage-grouse’s survival.

The Owyhee is home to 14 species of bats.

It is estimated that there are at least 28 species of plants that are found nowhere else in the world save the Owyhee, including Packard’s blazing star and the Owyhee clover.

What states does the river cross?

Oregon

want to learn more?

Everything about the Owyhee is big. The landscape, the threats — and the opportunities we have to protect it. Learn more and take action:

Explore the one-of-a-kind Owyhee Canyonlands: https://www.owyheewonders.org/

Learn more about the growing coalition of people working to protect the Owyhee Canyonlands: https://wildowyhee.org/

Thank Oregon Senators Wyden and Merkley for introducing the Malheur Community Empowerment for the Owyhee Act: https://wildowyhee.org/thank-your-senators/

Thanks to the work of this collaborative to reach an agreement, Oregon Senators Ron Wyden and Jeff Merkley introduced the Malheur Community Empowerment for the Owyhee Act in late 2019 to codify the principles of economic security for rural communities while establishing durable conservation protections for the Owyhee Canyonlands.