Yadkin Pee Dee River

The Yadkin Pee Dee River Basin covers more than 7,200 square miles of the Carolinas connecting the mountains of northwestern North Carolina to the Lowcountry of South Carolina. From its headwaters near Blowing Rock, the Yadkin River flows east and then south across North Carolina’s densely populated midsection. It travels 203 miles — passing farmland; draining the urban landscapes of Winston-Salem, Statesville, Lexington and Salisbury; and fanning through seven man-made reservoirs before its name changes to the Pee Dee or Great Pee Dee River below Lake Tillery. The Great Pee Dee is a free-flowing river for another 230 miles to the Atlantic, leaving North Carolina near McFarlan, meandering through the South Carolina towns of Cheraw and Gresham, and the Waccamaw National Wildlife Refuge and ending its journey at Winyah Bay in South Carolina. It is the principal source of water for the central Carolina region; however, it is threatened by industrial pollution, population growth and poor management.

Since it originates in the Blue Ridge and drains portions of the Piedmont, Sandhills and Coastal Plain, the Yadkin Pee Dee River Basin contains a wide variety of habitat types, as well as many rare plants and animals. The basin’s rare species (including endangered, threatened, significantly rare or of special concern) include 38 aquatic animals. Two species are federally listed as endangered — the shortnose sturgeon, a migratory marine fish that once spawned in the river but has not been spotted in the basin since 1985; and the Carolina heelsplitter, a mussel now known from only nine populations in the world, including the lower basin’s Goose Creek. Five new species, all mollusks, have been added to the state’s endangered species list — the Carolina creekshell, brook floater, Atlantic pigtoe, yellow lampmussel and savannah lilliput.

Forests cover half of the basin, including the federal lands of the Pee Dee National Wildlife Refuge, the Blue Ridge Parkway, Uwharrie National Forest and the Waccamaw National Wildlife Refuge which lies completely within the basin. Most of the watershed’s forestland is privately owned though. Nearly one-third of the watershed is used for agriculture, including cropland (15.6 percent) and pastureland (14.1 percent). Just 13 percent of the land is developed, although this figure is rising rapidly.

The Backstory

The Yadkin Pee Dee River provides residents and visitors with a host of benefits, including scenic views, recreational and economic opportunities, clean drinking water and floodwater storage. However, the river and riverside lands that provide these values are at risk due to population growth and poorly planned development. Increasing water demand has led to more competition for the limited water resources available while outdated water reclamation facilities are causing unnecessary spikes in pollution. Riverside forests are also being cleared to make way for new development and forest products which increases polluted stormwater run-off that contaminates streams and pose challenges to drinking water treatment. High Rock Lake- south of Winston-Salem, NC- experiences dangerous and unnatural algal blooms due to the poor water management system in the upper portion of the river. Logging operations for wood pellet production have decimated wetlands critical to filtering pollutants out of stormwater and absorbing floodwaters. Additionally, numerous large and small dams clog the river disconnecting the natural flow through the system. These issues are exacerbated by the prolific growth of underregulated poultry farms that have questionable waste management strategies around water protection.

The Yadkin river has been significantly impacted by numerous dams built on it. The uppermost reservoir is W. Kerr Scott Reservoir. The southern portion of the Yadkin has been impounded by a chain of six reservoirs: High Rock, Tuckertown, Badin (Narrows), Falls, Tillery and Blewett Falls. The first four built in the first half of the 20th century to power Alcoa’s aluminum smelters and later two were built to provide power to the region. High Rock is the first and largest of the Yadkin chain lakes. Badin, the oldest, was built in 1917 just below the gorge called “the Narrows” to power an aluminum plant in Badin. Alcoa’s smelting operations have been closed in NC and Cube Hydro now operates those dams to sell power and Duke Energy is licensed to operate the other two for its electric utilities. The Pee Dee River is then free flowing through South Carolina to the ocean.

The region is also experiencing impacts from climate change. Frequent flooding has caused damage to infrastructure and loss of property. The frequency and intensity of storm events are expected to escalate as climate change causes greater hurricane activity and associated rainfall. Drought conditions have also affected natural and human communities in the basin. Combined, these changes are exacerbating existing water quality and quantity issues in critical habitats along the river, posing greater treatment challenges for the region’s utilities, and creating financial burdens for local governments, families and businesses.

Looking to the Future

The development pressures in the watershed require better water management. The upper portion of the Yadkin River is sandwiched between development occurring in Winston-Salem and the growth of Charlotte. In the lower portion coastal development is pushing into the floodplain endangering critical habitats, threatening water quality and placing infrastructure, homes and businesses in harms way. Investing in the protection and restoration of these rivers and riverside lands is a cost-effective and sustainable solution to these pressing climate and growth challenges and will ensure that they are preserved for generations to come.

Efforts that are designed to protect and restore rivers should center the voices of communities who are most impacted rivers and river-related decisions. Communities advocate for their rivers when they are connected to their rivers. Whether those connections include recreation, subsistence, advocacy, environmental education, sustainable economic development or other activities, communities should be supported in connecting to their local rivers in ways that address their needs, values and interests.

Collaboration between diverse partners including community leaders, local governments, conservation organizations and businesses is needed to build the financial support, knowledge, natural infrastructure, policies and community capacities needed to promote equitable watershed management strategies that safeguard clean water and build resilience for people and wildlife.

The growing communities of the watershed should look to use water management strategies that find the full value of water- such as an integrated water management or One Water approach. These strategies define the value of the natural landscapes and utilize water management strategies that mimic the natural processes- like green stormwater infrastructure and floodplain restoration.

The relicensing of the Cube Hydro and Duke Energy projects were completed between 2010 and 2018 and the projects will be improving their water quality and land protection investments in the coming years over the course of the license.

The poultry operations in the watershed continue to grow and more oversight is needed to ensure that ecological damage is avoided and sustainable agricultural operations are encouraged in the watershed.

Yuba River

An Enduring Sierra Classic

The Yuba River is a California classic. In the best sense, that includes the giant, polished granite boulders and emerald green water that creates cascades perfect for whitewater paddlers during high spring flows, transforming to idyllic swimming holes in the warm summer months.

Rising on the eastern border of the Tahoe National Forest, the Yuba’s North, Middle, and South Forks all have distinct characteristics, but each shares the beauty of the Sierra Nevada surroundings—and the legacy of mining and hydropower that comes with it.

Did You know?

The millions of cubic yards of hydraulic mining debris carried down the Yuba River raised stream beds up to 50 feet in some places, increasing flood risks. Hydraulic mining was eventually banned in 1884 due to the impacts of the debris flows on farming.

Much of the hydraulic mining debris remains as the “Yuba Goldfields,” a 10,000-acre riverside plot of oddly shaped gravel mountains, ravines, and pools created as mine waste flushed downstream.

Englebright Dam was built in 1941 to trap mining debris following the re-legalization of hydraulic mining in the 1930s. Today Englebright serves primarily for hydroelectricity generation.

The region’s historic gold rush once made it one of the most productive placer mining rivers in California, with operations quickly turning into large-scale industrial hydraulic mining before the practice was banned. And the steep, narrow canyons proved just a little too tempting to aquatic engineers, who left their mark with more than 30 dams, 20 powerhouses, and 500 miles of canals sprawling across the watershed.

Between reservoirs and hydropower installations lie miles of top-tier whitewater runs that draw paddlers from around the West to the various forks of the river with a captivating wilderness feel despite often close proximity to roads. The undammed North Fork drains the beautiful Sierra Buttes that provide a lookout all the way to Mt. Shasta to the north and west to Mt. Diablo in the Bay Area. And the snowmelt runoff provides excellent cold water habitat for trout and reintroduced historic species like Chinook salmon and steelhead.

A state Wild and Scenic River, the South Fork Yuba is the centerpiece of the South Yuba River State Park that stretches 20 miles to Englebright Reservoir, formed by a dam across the Yuba River’s main stem. The Pacific Crest Trail is among several passing through the watershed, making the area popular with backpackers, and a network of mountain bike trails pulls in fat tire fans.

In keeping with California culture, members of a local colony of artists, poets and musicians affectionately known as the “Yuba Nation” frequent the river for inspiration in summer months and to protest dams and other potential impacts to the river as they arise.

The Backstory

The Yuba River watershed is home to some of the first hydropower dams in California, in some cases dating back to structures built during the gold-rush era. These dams block access for anadromous fish along the 1,339-square-mile watershed that is considered one of the last remaining strongholds for Chinook salmon and steelhead runs.

Dams owned by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Yuba County Water Agency, Nevada Irrigation District, and Pacific Gas & Electric affect more than 250 miles of rivers by reducing stream flow levels, altering habitat, and affecting native amphibians and resident fish.

The threat of hydropower dams placed the Yuba River on the America’s Most Endangered Rivers® report for 2011. Meanwhile, remains from hydraulic mining operations are prevalent along the Yuba River, although restoration efforts along the altered Lower Yuba River are in progress.

The Future

Dams on the Yuba—including Englebright Reservoir, Bullards Bar hydroelectric dam, and Daguerre Point Dam—are currently going through the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) relicensing process, offering American Rivers an opportunity to push for improved stream flows, river habitat, and recreation access. Most significantly, it offers the opportunity for reintroduction of salmon and steelhead into their historic habitat in the upper Yuba basin.

For the foreseeable future, that reintroduction will come in the form of a “trap and transport” program circumventing the 260-foot Englebright Dam to reach the abundance of quality fish habitat found on the Yuba’s North Fork. As California continues to experience climate change and considers how to adapt to future climate conditions, fishery managers have come to recognize the importance of reintroducing salmon and steelhead to historic habitat at higher, and thus cooler, elevations to promote their recovery.

Until a realistic longterm solution is attainable, the transport method is the most effective way to return these fish to the Sierra Nevada for the first time in perhaps a century. Cold water flowing out of Englebright Dam combined with AR’s habitat restoration work on the lower Yuba River offers additional opportunity to establish a robust downstream fishery for spring-run Chinook and steelhead.

Ventura River

The Ventura River flows approximately 16 miles from the confluence of Matilija Creek and North Fork Matilija Creek to the Ventura River Estuary at the Pacific Ocean. With Matilija Creek, the river is 33 miles long. The 220-square mile watershed is made up of the Santa Ynez Mountains, chaparral, and the cities of Ojai and Ventura. The northern portion of the watershed is part of Los Padres National Forest, while the southern portion is made up of communities and agriculture, including cattle, citrus, and avocadoes.

WHAT STATES DOES THE RIVER CROSS?

California

Threats to This River

No imported water is used within the Ventura River watershed, meaning that the residents use entirely local water supplies. The watershed also hosts a number of organizations dedicated to volunteer water quality monitoring, river restoration and advocacy for the removal of the Matilija Dam on Matilija Creek. The Surfrider Foundation and the Matilija Coalition, along with other agencies and organizations, have developed three dam removal concepts which focus on reducing the removal cost and also maximizing benefits. Removal of the 190-foot tall dam would open nineteen miles of Steelhead spawning habitat.

The relatively high levels of rainfall in the river’s headwaters compared to rainfall levels at the coast contribute to flash flood conditions along the steep terrain of this watershed, which have historically damaged citrus groves, and a wastewater treatment plant.

Yampa River

Gorgeous gorges, wild and free

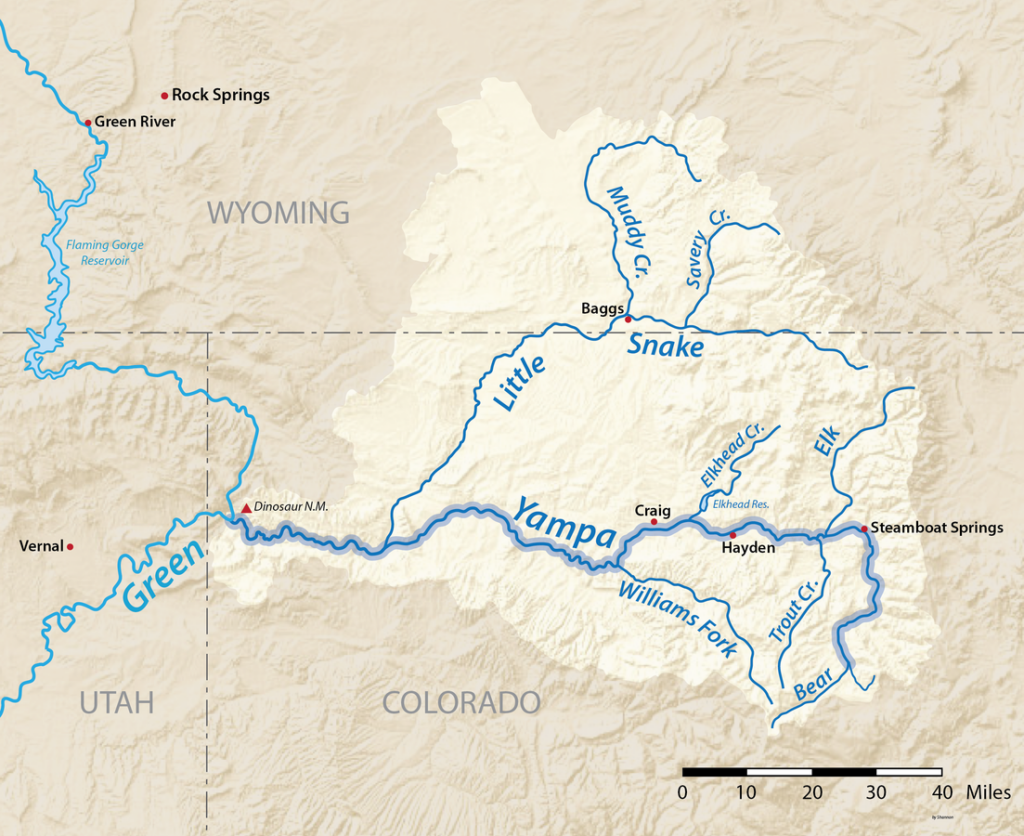

Rising from the Flat Top Mountains in northern Colorado, the wild Yampa River is one of the West’s best floats. It’s a recreational paradise pausing only briefly for a pair of relatively small storage reservoirs high in the basin that spill with spring runoff to retain the character of a free-flowing stream.

As a result, the unregulated Yampa runs free for almost its entire 300-mile journey to Dinosaur National Monument, where it joins the Green River at Echo Park. There it boasts one of the West’s most famous scenic floats at Yampa Canyon, which was the site of one of the nation’s most famous conservation battles when it narrowly escaped being dammed at its mouth in the 1950s. Had that proposed hub of the Colorado River Storage Project succeeded, it would have flooded the Yampa some 45 miles upstream to Deerlodge Park and the Green another 67 miles to Flaming Gorge Dam, and established a dangerous precedent of dam building in a national parks and monuments.

Instead, not one, but two of the world’s greatest multi-day floats remain (Yampa Canyon and Gates of Lodore on the Green). As the river passes through a 2,500-foot cut in the Uinta Mountains, boating Yampa Canyon is more about scenery than whitewater thrills. Rounded buttes and varnished slickrock walls punctuated by towering hoodoos dating back a billion years greet the fortunate few to win launch dates in the annual permit lottery designed to minimize impact to the gorgeous gorge.

More intense whitewater can be found upstream in the Class 4-5 Cross Mountain Gorge or steep tributary creeks feeding the main stem near the resort town of Steamboat Springs, where a playful whitewater park hosts hundreds of kayakers, stand-up paddlers, and inner-tubers throughout the spring and summer. Between the waves, anglers enjoy world class trout fishing meandering through pastoral rangeland and into the rural agricultural towns of Hayden, Milner, Craig and Maybell.

Did You know?

The Yampa River is one of a few river homes to four endangered fishes – the humpback chub, bonytail, colorado pikeminnow, and razorback sucker.

The Colorado pikeminnow can reach six feet long and is one of the world’s largest minnows.

The Yampa provides about one third of Colorado’s contribution to the Colorado River.

The Yampa’s peak recorded flow was 33,200 cfs at Deerlodge Park on May 18, 1984.

WHAT STATES DOES THE RIVER CROSS?

Colorado

The Backstory

Yampa Canyon and Dinosaur National Monument provided the launch site for the river conservation movement when a proposed dam at Echo Park was defeated more than 60 years ago. Today, dam builders are looking farther upstream, including a potential pumpback project that would transfer water across the Continental Divide to quench the thirst of Colorado’s rapidly growing Front Range communities.

Right now, the Yampa provides world-class recreation, is the source of a thriving agricultural economy, serves as the life blood for endangered fish species, and drives local economies from Steamboat Springs to Vernal, Utah. A large-scale diversion would have dramatic impacts on river function all the way to Lake Powell. Not only would it be an ecological disaster for the Yampa and the Upper Colorado River basin, it would cost billions of dollars, putting a huge burden on Colorado taxpayers and water rate payers.

The Future

Beyond the Yampa’s known entities lie several hidden gems. Little Yampa Canyon, Juniper Canyon, and Cross Mountain Gorge have all been determined as suitable for Wild and Scenic River designation by the Bureau of Land Management, prompting the Colorado River Conservation District to abandon conditional water rights for reservoirs that would have flooded those areas. Though still lacking formal W&S designation, they remain free to explore and are often visited by participants in the booming recreation economy surrounding Steamboat Springs.

While water requirements for potential shale-oil development remain a threat in the face of climate change, drought-diminished flows, and warming water temperatures conducive to invasive fish species like smallmouth bass and northern pike, collaborative efforts to protect Yampa River flows continue to succeed. The Colorado Water Trust has leased water from the Upper Yampa Conservancy District to help bolster flows for anglers and tubers later in the summer. And a sincere effort is underway to permanently protect flows required for endangered fish survival in the Yampa by advancing in-stream flow appropriations in the lower reaches through Dinosaur.

Verde River

Turning water into wine

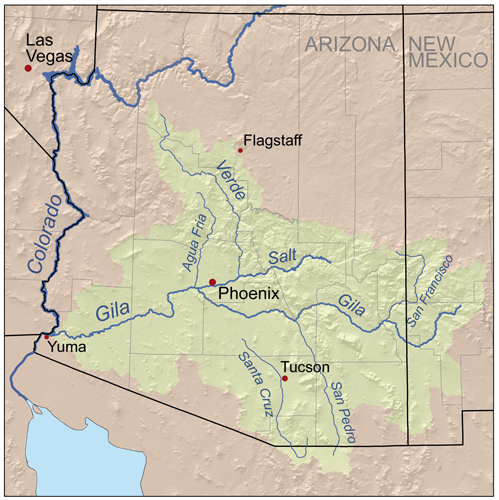

The Verde River is already about halfway through its 180-mile journey before it really becomes recognizable as a river. But by the time it accumulates enough of Arizona’s patchy precipitation about 30 miles southwest of Flagstaff, it blossoms into a perennial gem that passes through one of the most beautiful places on earth.

Just beyond the burgeoning Sedona-Verde Valley, the Verde grows large enough for mild whitewater boating in a unique and breathtaking landscape rich with wildlife and steeped in history.

Several stretches are ideal for canoeing, kayaking, or SUP adventures, but maybe none more enticing than the 40-mile segment recognized as the first of only two Wild and Scenic Rivers in Arizona, along with downstream tributary Fossil Creek.

The shallow, rugged canyon below Beasley Flats combines slightly spicier whitewater with stunning desert scenery rimmed by red rock bluffs and tiered with cactus-covered hillsides above a lush riparian corridor along the river’s edge.

Making its way into the Mazatzal Wilderness, Arizona’s largest, the Verde is a magnet for waterfowl and dozens of other bird species dependent upon its vital oasis amidst arid desert uplands. The high-quality habitat supports more than 50 threatened, endangered, sensitive, or special status fish and wildlife species.

Hikes galore offer chances to see ancient cliff dwellings in side canyons and trails that climb nearby ridges, including Montezuma Castle National Monument near Camp Verde. Like the early inhabitants that first made their home there, newer communities surrounding the river corridor depend upon the Verde still. Rather than irrigating subsistence crops, though, the modern focus is on tourism established in part through river recreation and a growing local wine industry, high yield harvests that keep more water in the river than row crops like cotton and alfalfa that have depleted the resource historically.

Did You know?

Wine production in the Verde Valley generates about $25 million annually, employs over 100 people and accounts for $6.5 million in spending at tasting rooms, vineyards and wineries.

Grapes are an ecologically sound crop using 1/10th of the water per acre that cotton or other row crops consume.

The Verde’s riparian and associated upland habitat supports over 60 percent of the vertebrate species that inhabit the Coconino, Prescott and Tonto National Forests.

The earliest hydropower plant in Arizona (now decommissioned) is located in the Verde corridor, as are the remains of one of the state’s first tourist developments, the Verde Hot Springs Resort.

WHAT STATES DOES THE RIVER CROSS?

Arizona

The Backstory

Much of the Verde Valley’s history can be traced back to a legacy of copper, gold, and silver mining in the surrounding hillsides, with little emphasis on the river once the hunter-gatherer Hohokam and Sinagua people disappeared. Market collapses led to yet another cultural shift as the spirit of mining towns abandoned in the 1950s has been rekindled through eco-tourism and a new-age metaphysical subculture.

Where nearby Sedona and the Oak Creek tributary of the Verde have long been on the tourism map, the greater Verde Valley has only recently begun to come into its own. The influx of visitors is a big boon to local economies, but it can put significant strain on natural resources already stretched thin by overuse and excessive withdrawals for outdated agriculture and growing municipalities.

Downstream, booming southwestern cities with scarce water sources render rivers like the Gila, the Salt, and its largest tributary, the Verde, almost entirely used up by the time they pass through the megalopolis of Phoenix. Should water levels in Lake Mead continue to drop, the remainder of the Verde River could easily become a target for central Arizona water supply.

The Upper Verde River

American Rivers and partners are hard at work in efforts to designate the Upper Verde River as Arizona’s next Wild and Scenic River. Check out these videos from Wild and Scenic Rivers Hill Week 2024 when the Upper Verde Wild and Scenic River Coalition met with members of Congress to discuss making this designation happen!

The Future

In the wake of Wild & Scenic designation, small towns like Jerome, Clarkdale, Cottonwood, and Camp Verde have come to embrace the river and are actively seeking ways to connect it to their communities as a lifestyle amenity. Those efforts are paying off.

Recognizing the economic benefits and lifestyle draw of a healthy river, even local businesses are getting on board. Mining conglomerate Freeport-McMoRan has set aside a conservation easement on the upper Verde River as a contribution to the quality of life the surrounding community hopes to maintain and carry into the future.

Yellowstone River

A Wildlife Paradise

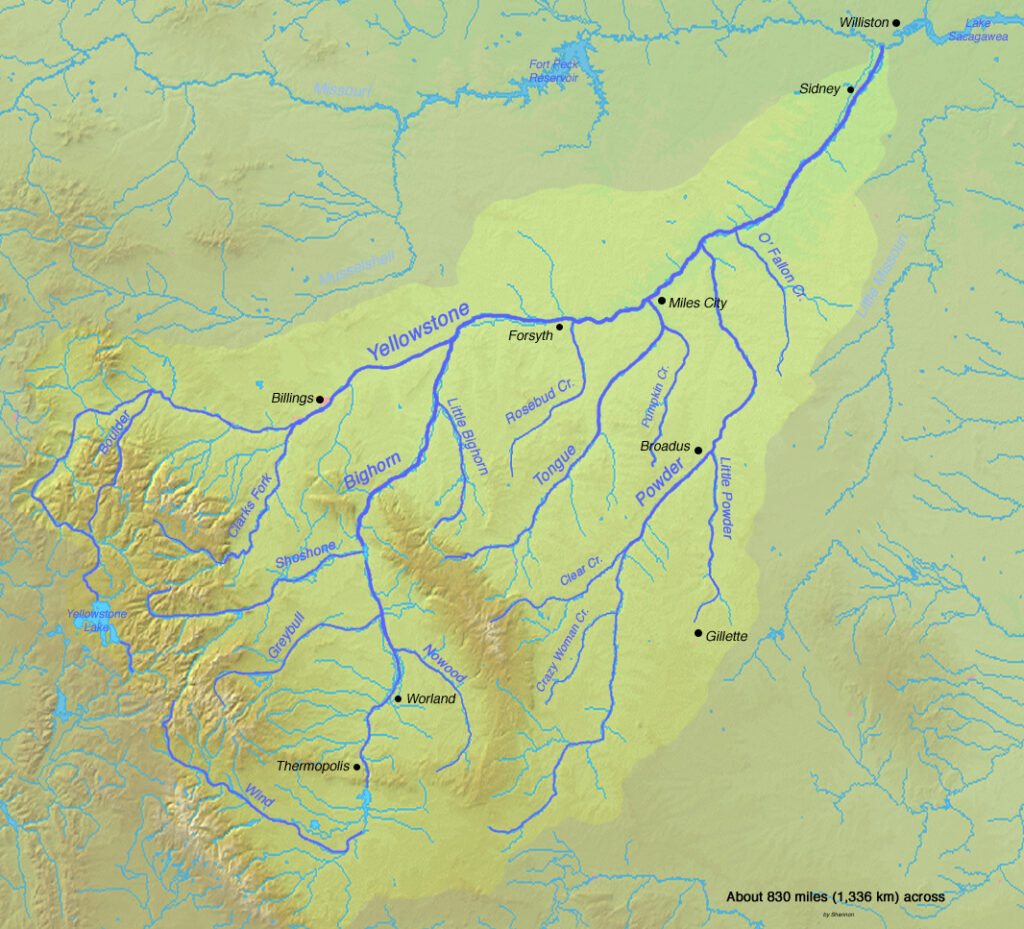

Rivers radiate in every direction from America’s first national park. But only one merits the name Yellowstone. Although its headwaters lie just outside the declared park border in Wyoming’s southern Absaroka Range, the Yellowstone River knows no bounds.

Cutting a diagonal northeast channel across Montana for nearly 700 miles to its confluence with the Missouri River in North Dakota, the Yellowstone River is the longest free-flowing river in the lower 48 states. Within and around Yellowstone National Park, its prestige is punctuated by picturesque waypoints including aptly named Inspiration Point overlooking the thunderous Upper and Lower Falls of the Yellowstone, plummeting 109 feet and 308 feet, respectively, into the near mythical Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone and Black Canyon of the Yellowstone beyond.

North of Yellowstone Park, the river passes through the sublime Paradise Valley, which offers more than 100 miles of Montana’s most popular floating and fishing as it flows casually between the Gallatin and northern Absaroka mountains. The Blue Ribbon trout fishery gradually transitions to cool water habitat along the Great Plains near Billings, where endangered Pallid sturgeon and similarly prehistoric-looking paddlefish join the system.

Throughout the Yellowstone River corridor, wildlife ranges from bald eagles to elk, whitetail deer, black and grizzly bears, native Yellowstone cutthroat trout, and so much more. Recreational activities including fishing, hunting, rafting, wildlife watching and even agate-hunting are incredibly popular along the Yellowstone and are a vital part of the local economy.

Did You know?

The Yellowstone River is considered the principal tributary of the upper Missouri.

At 692 miles, the Yellowstone is the longest free-flowing river in the Lower 48. Its headwaters in the southern Absaroka Mountains are located as far from a road as you can get in the Continental U.S.

The Gallatin, Madison, Snake, Shoshone, Clarks Fork, and Fall River are all major rivers originating in Yellowstone National Park.

Unlike most other national parks, boating is forbidden within Yellowstone National Park, leaving it with more than 400 miles of virtually unexplored rivers.

WHAT STATES DOES THE RIVER CROSS?

Montana, Wyoming

The Backstory

To this day, the defeat of the massive dam proposal that would have flooded Paradise Valley remains one of the greatest environmental victories in Montana’s history. Recreation-minded conservationists joined together in the 1970s to thwart the dam proposed in Allenspur Canyon that would have forever altered the landscape, ecology and economy of the region.

The biggest threat to the Yellowstone River today comes from unwise floodplain development. Widespread channelization projects in the form of levees and rip-rap put a straightjacket on the river and eliminate floodplain access and important side-channel habitat. In the Paradise Valley portion of the river through Park County, 25% of the riverbanks have been altered. The threat of further alterations landed the Yellowstone River on our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® list in 1995, 1999, and 2006.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers eventually responded by developing a Special Area Management Plan for the Park County reach of the river that put new limits on where and what types of channelization projects will be allowed. The plan was completed in 2011.

The Future

Poorly-constructed oil pipelines have proven prone to rupturing during floods and ice jams, leading to disastrous oil spills in the lower Yellowstone River in 2011 and 2015. Equally pressing, a proposed new dam downstream from Glendive could severely impede fish passage for endangered pallid sturgeon and many other native fish species. American Rivers vigorously opposes that proposed dam and is advocating for removal of the existing Intake Diversion Dam that currently obstructs the fish. The Corps of Engineers has been studying ways to improve fish passage around the diversion for years and is expected to issue a Draft Environmental Impact Statement in the summer of 2016.

Well upstream, the problem is the exact opposite. Invasive lake trout discovered in Yellowstone Lake in the 1990s have wreaked havoc on the entire ecosystem of Yellowstone National Park and efforts remain ongoing to remove the voracious predators that have depleted native trout in the lake by more than 90 percent. More than 40 bird and mammal species within the park feed on Yellowstone cutthroat trout, qualifying the fish as a keystone species with a disproportionately large impact on the food chain. American Rivers supports efforts to remove the lake trout before their impact is felt downstream.

St Louis River

Superior Waterway

The call of the wild may be no stronger anywhere in the lower 48 than the headwaters of the St. Louis River. Beginning in the Laurentian Uplands, where small streams divide in three directions toward Hudson Bay, Lake Superior, and the Mississippi River, it’s a land of timber wolves, moose, and Canada lynx. Wood turtles, sturgeon, walleye, northern pike, bass, bluegill, black crappie, channel catfish, and 163 species of breeding birds call the river home, savoring lush wetlands and wild rice lakes that led the Ojibwa people to settle the region.

This 194-mile river, which drains 2.4 million acres of Minnesota’s northern forests and wetlands, remains the primary reservation fishery for the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa. Below the reservation, it flows through the magnificent Jay Cooke State Park and into a rare freshwater estuary between the twin ports of Duluth, MN, and Superior, WI, where it enters Lake Superior as the largest U.S. tributary of the entire Great Lakes system. The lower St. Louis is the only river in the state with whitewater rafting opportunities.

The Backstory

Historically, the estuary was heavily impacted by industry, resulting in designation as a Great Lakes Area of Concern after the lower river became one of the most heavily polluted waterways in the state by the mid-20th Century. It still hosts the busiest port on the Great Lakes. However, an investment of more than $1 billion and a commitment to restoration and economic development by the City of Duluth has the lower St. Louis well on its way to recovery.

Upstream, the main stem of the St. Louis River and several of its larger tributaries have been dammed for hydropower generation, disrupting connectivity and increasing mercury bioaccumulation in fish. Additionally, the St. Louis River and its tributaries have been adversely impacted by more than a century of iron mining, with the loss of thousands of acres of headwaters wetlands and streams.

Did You know?

Jay Cooke State Park, one of the 10 most visited in Minnesota, celebrated its 100-year anniversary in June 2015.

The rocky gorge of the St. Louis River at Jay Cooke State Park was not navigable to canoes, so Native Americans blazed a 6.5-mile portage around it. Later voyageurs dubbed it the “Grand Portage of the St. Louis.”

Duluth, MN, at the mouth of the St. Louis River at Lake Superior was named for Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Lhut, the first European to explore the area in 1679.

WHAT STATES DOES THE RIVER CROSS?

Minnesota

The river found its way onto the America’s Most Endangered Rivers® list in 2015 due to the threat of sulfide-ore mining. This type of mining releases copper and nickel bound up in sulfide-bearing rock, and commonly results in acid mine drainage and increased levels of heavy metals and sulfates in downstream waters. Allowing this type of mining in the St. Louis River and Boundary Waters regions of Minnesota will ruin wild places and contaminate water for people, fish and wildlife.

Increased sulfate degrades wild rice stands and contributes to already high mercury levels in fish that threatens public health. A 2013 study by the Minnesota Department of Health found that 1 in 10 infants on the North Shore of Lake Superior are born with unsafe levels of mercury in their blood, potentially impairing normal development.

The first of the new mining proposals, PolyMet Mining’s NorthMet Project, would destroy 1,000 acres of wetlands and indirectly impact thousands more wetland acres. It would also require a complex federal land exchange resulting in the turnover of more than 6,000 acres of biologically rich lands from the Superior National Forest and the St. Louis River watershed to mining companies.

The Future

Now comes the bad news. Earlier in 2016, the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR) decided to allow PolyMet to move its mining project forward to the permitting stage despite the reality that no mine of this type has operated and closed without polluting nearby lakes, rivers and streams.

Minnesota Gov. Mark Dayton recently stated his support for protecting the nearby Boundary Waters from similar sulfide-ore mining, clearly acknowledging the risks inherent in this type of mining. The St. Louis River and its communities, tribes and wildlife deserve the same consideration and protection against sulfide-ore mining. If this project is allowed to proceed, there is no turning back.

White Salmon River

Wild Fish and Scenic Whitewater

Few things in life can top the intoxicating thrill of riding a whitewater raft or kayak down glacial runoff pouring from the flanks of a 12,000-foot volcano. Yet, in 2011, the White Salmon River found a way.

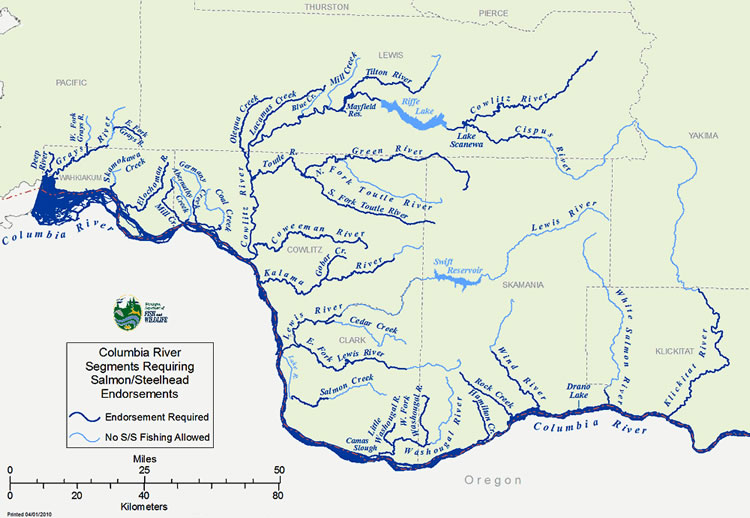

That was the year demolitions experts blew a gaping hole in the base of the 125-foot tall Condit Dam and reconnected the entirety of the White Salmon to the Columbia River, allowing the return of the once-abundant runs of wild salmon and steelhead that had provided physical, spiritual, and cultural nourishment to local Native American tribes. As an added bonus, the dramatic dam removal extended the whitewater thrill ride another five miles downstream, carrying paddlers all the way to the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area.

Not that the White Salmon is lacking for scenery in its own right. This iconic southwest Washington river flows from the snowy slopes of Mount Adams for 45 miles, more than 25 of which are federally designated as Wild and Scenic. The steep, breathtaking canyons and crystal clear water help drive a robust tourism and recreation industry around the river nationally recognized as a premier whitewater destination.

Ten outfitters run commercial trips on the river, and at least 25,000 boaters use the White Salmon each year, bringing an important economic influx to the local community. Paddlers now floating past the former dam site struggle to recognize the plug was ever there.

Did You know?

In addition to salmon and steelhead runs, the White Salmon is among the top three resident rainbow trout fisheries in the region.

The White Salmon offers Class III-IV whitewater in a natural setting that remains runnable virtually year-round.

At 12,307 feet, Mt. Adams (headwaters of the White Salmon) is the second highest peak in the Pacific Northwest after Mt. Rainier.

Condit Dam was the largest dam ever removed in the United States until the Elwha Ecosystem Restoration Project on the Olympic Peninsula removed the larger Elwha Dam and Glines Canyon Dams.

WHAT STATES DOES THE RIVER CROSS?

Washington

The Backstory

Built in 1913 to generate hydropower, Condit Dam was an important part of the history and development of the area. But the benefits came at a high cost. The towering dam disrupted natural river flows and was built with no fish passage, limiting salmon and steelhead to the lower three miles of river.

Condit ultimately created more ecological problems than it did electricity (an average of just 10 megawatts) and soon outlived its usefulness. Faced with the mounting costs of operating the aging dam, owner PacifiCorp signed an agreement in 1999 with diverse interests including American Rivers, the Yakama Indian Nation, government agencies, and other partners to remove it.

When the hole was blasted in Condit’s base in October 2011, the reservoir behind it drained in a matter of hours. Today, salmon have returned to historic upstream spawning grounds on the free-flowing river and the number of whitewater paddlers visiting the White Salmon continues to grow.

The Future

With the White Salmon once again flowing freely into the Columbia River, migrating salmon and steelhead have only the Bonneville Dam just downstream from the confluence to overcome. Bonneville does include fish ladders, although the large concentration of salmon awaiting their opportunity to swim upstream now attracts several California sea lions who prey on the fish. The dam has also blocked the upstream spawning migration of white sturgeon, although they still spawn in the Columbia River below Bonneville.

In 1986, the lower White Salmon between Gilmer Creek and Buck Creek earned Wild and Scenic designation, followed by a longer segment of the upper river between the headwaters and the boundary of the Gifford Pinchot National Forest in 2005. Further support for the Wild and Scenic campaign will help keep development threats in check and ensure the river will remain in its relatively pristine state for generations to come.

Teton River

A Tale of Two Rivers

The Teton is the last major free-flowing river in eastern Idaho. And apparently it intends to stay that way.

The 81-mile tributary of the Henry’s Fork that drains the placid Teton Valley along the Idaho-Wyoming border reasserted its stature as a wild, free-flowing river in 1976, when the Teton Dam failed catastrophically as it was being filled for the first time. The ensuing deluge claimed the lives of 11 people and 20,000 head of livestock while causing $2 billion in property damage as it gushed downstream. It is considered one of the worst dam failures in U.S. history.

The force of the failure took an incalculable toll on native fish and wildlife in the Teton River Canyon as water and debris washed away riparian zones and reduced the canyon walls. The river canyon has since recovered to provide vital habitat for native Yellowstone cutthroat trout along with the thousands of elk, mule deer, and trumpeter swans that overwinter in the canyon.

What remains is a Western treasure that serves as one of the last strongholds for imperiled Yellowstone cutthroat trout. The tranquil upper valley draws drift boats and dry-fly fishermen, while the rugged and scenic lower river supports a tremendous, albeit lightly used wild-trout fishery and stellar whitewater boating during the high water months.

Did You know?

Although it flows almost entirely in Idaho, the Teton River actually originates in Wyoming, on the west side of the Teton Range.

The Teton River bifurcates into two distributaries—the Teton and South Fork Teton—that merge with the Henry’s Fork at two different locations.

When the Teton Dam failed in 1976, an estimated 80 billion gallons of water scoured the town of Rexburg, ID, site of the Teton Flood Museum.

WHAT STATES DOES THE RIVER CROSS?

Idaho, Wyoming

The Backstory

Geologists and engineers recognized how poorly suited the porous soil and rock at the foundation of the Teton River Canyon is for a dam site, but that didn’t prevent the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation from building the earthen Teton River Dam there anyway. Nor did it dissuade the Idaho Legislature from appropriating $400,000 in 2008 to fund a study on rebuilding the Teton Dam, the most recent of many attempts to do so since the original dam failed. Technically, it’s still an authorized dam site.

Beyond the obvious risks, rebuilding the Teton Dam would destroy a tremendous wild-river recreational resource that thrives in large part due to the vital habitat it provides for Yellowstone cutthroat trout and countless other wildlife species. The dam would also create a barrier to higher elevation tributary streams, preventing fish from reaching the coldwater habitats they will need as the climate warms.

The Future

Fortunately, this time around the Bureau of Reclamation has placed rebuilding the Teton Dam low on its list of projects that can meet eastern Idaho’s future water supply needs without inflicting serious environmental damage. American Rivers also took part in the recent study of potential dam sites for the region and helped quash the idea of rebuilding Teton Dam, at least for the time being. Until it is permanently protected, threat of a new dam still lingers.

That’s why we’re advocating for a Wild and Scenic suitability study to determine if the Teton River Canyon and three of its major tributaries (Badger, Bitch, and Canyon creeks) should be added to the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. Wild and Scenic designation would forever protect them from new dams, dewatering and other threats. The U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM) plans to begin the study in 2016.

Meanwhile, improved water-conservation measures, aquifer recharge and creative water marketing strategies remain effective options for improving water supplies in lieu of a dam.

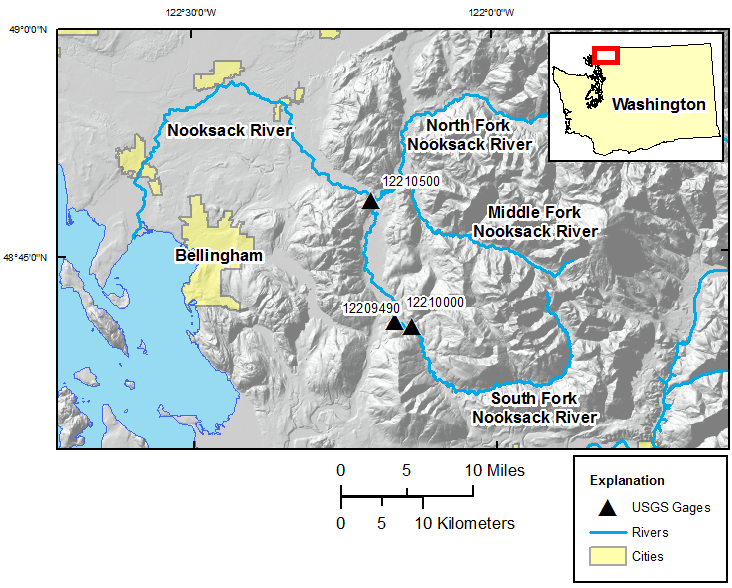

Nooksack River

The only thing it lacks is the Wild and Scenic label

The Nooksack River puts the great in the Great Northwest. Its spectacular North Fork is the northernmost river in Washington, running wild with icy glacial snowmelt from the snowfields of 10,778-foot Mount Baker and 9,127-foot Mount Shuksan in North Cascades National Park, before being joined by the Middle and South forks as it weaves through forests and farmlands on its way to the Salish Sea in Puget Sound north of Bellingham.

With volcanic Mt. Baker and the Twin Sisters Range of the jagged North Cascades dominating the surrounding landscape, the upper river was shaped as much by fire as ice through the millennia, creating a one-of-a-kind watershed treasured for its vast array of scenery and recreation. Whether it’s whitewater paddling beneath (or skiing atop) towering snowcapped summits; fishing in ancient forests for five species of native salmon, steelhead, resident rainbows, and cutthroat trout; hiking past waterfalls on the nearby network of trails; or scoping out abundant bald eagles, black bears, mountain goats, elk, spotted owls and even the rare bull trout, the Nooksack does not disappoint.

If there is a downside, it is found in lack of permanent protection for this great Northwestern treasure. Such high-quality habitat is increasingly rare and valued by millions for the clean water it provides for drinking, farming, outdoor recreation, and tourism. A cultural mix of native tribes, heritage farm towns, burgeoning New West communities, and the wildlife surrounding them all depend upon an unspoiled Nooksack River connecting glacial headwaters with the sea. Yet the majority of this vital river system remains deprived of even the most fundamental protection.

Did You know?

Mt. Baker (feeding the Nooksack River) is one of the snowiest places in the world. In 1999, Mt. Baker Ski Area set the world record for recorded snowfall in a single season—1,140 inches.

The endangered Marbled Murrelet is a small Pacific seabird that nests in old growth forests surrounding the Nooksack but has declined in numbers since humans began logging in the region.

The Nooksack Indian Reservation is in Whatcom County Washington. Whatcom was the name of a Nooksack chief and means “noisy water” in the Nooksack language.

What states does the river cross?

Washington

Other Resources

Check out these other resources to learn more about the river:

Nooksack Wild and Scenic Campaign website

The Backstory

The Nooksack Wild and Scenic effort is about conserving the ecological and recreational values of this magnificent river system. A diverse array of interested citizens, business owners, and organizations has worked for years to build widespread public support for Wild and Scenic River legislation designed to permanently protect over 100 river miles and 32,000 acres of riverside habitat in the upper Nooksack basin, including portions of all three forks and eight tributary streams.

Like much of the Northwest, some 40 hydroelectric dams have been proposed for various sites on the Nooksack since the 1970s, the legacy of logging impact remains along portions of the river, and a diversion dam on the Middle Fork has blocked passage of salmon and steelhead for nearly 70 years. Tremendous efforts are underway to restore the ecological health and improve the habitat of the Nooksack River and protecting the headwaters as Wild and Scenic would help protect these investments in restoration.

The Future

Keeping the Nooksack great remains a top priority in the region. Wild and Scenic designation would ensure that the river’s “Outstandingly Remarkable Values” are protected and enhanced in the future and prevent any new dams or other projects that would degrade the river’s natural character and healthy flows. The Nooksack Wild and Scenic campaign is working toward drafting legislation by 2017.

Recreational access around the river corridor is also a major concern and American Rivers is working with a variety of partners to implement recommendations in the Upper Nooksack River Recreation Plan, a planning effort spearheaded by American Rivers intended to improve access and guide recreational use in the region for the next 10-15 years. American Rivers is also an advisory committee member on Washington Department of Natural Resource’s new recreation planning effort called the Baker to Bellingham Recreation Plan.

In late 2020, American Rivers worked with several partners including Washington State Department of Natural Resources, Whatcom Land Trust, the Nooksack Tribe, American Whitewater, and others, with technical assistance from the National Parks Service, to finalize a plan for the Maple Creek Public River Access and Restoration Site. This site was identified in the Upper Nooksack River Recreation Plan as an ideal location for safe public recreation access along the North Fork Nooksack River, while also allowing natural resource managers to protect, restore, and enhance the adjacent riparian forest and natural river systems.

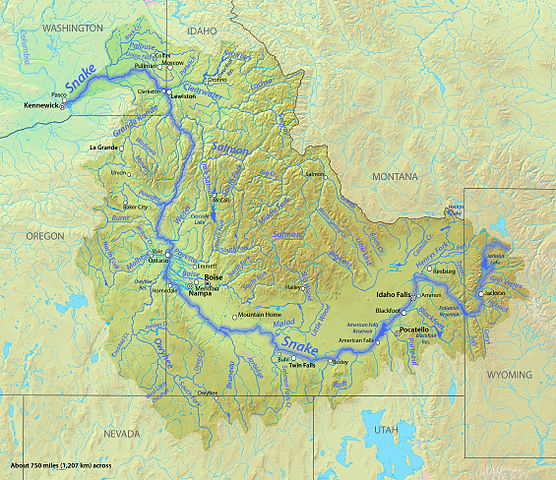

Snake River

The Snake River originates in Wyoming and arcs across southern Idaho before turning north along the Idaho-Oregon border. The river then enters Washington and flows west to the Columbia River.

It is the Columbia’s largest tributary, an important source of irrigation water for potatoes, sugar beets, and other crops. It also supports a vibrant recreation industry. A rare salmon fishing season in 2001 generated $90 million in economic impacts in Idaho, an amount that would more than double if wild salmon and steelhead are restored to the population levels of the 1950s.

The Snake River basin once produced about half of all spring chinook salmon returning to Columbia basin rivers. More than two million wild salmon and steelhead once returned to spawn in the Snake and its tributaries each year.

Today, these species are either extinct or threatened with extinction, as the most extensive freshwater salmon habitat in the lower 48 states is upstream of the four dams on the lower Snake.

Snake River salmon and steelhead begin their life’s journey high in the mountains of central Idaho, northeast Oregon, and southeast Washington. They then head out to sea, and after several years return to their natal rivers to spawn, an inland journey of more than 900 miles. The fish returning to the headwaters of Idaho’s Salmon River spawn at higher elevations than any other salmon and steelhead in the world.

Threats and Opportunities

Four U.S. Army Corps of Engineers dams and 140 miles of slack water reservoirs prevent salmon from migrating to and from the high-elevation spawning and rearing habitat in central Idaho, northeast Oregon, and southwest Washington.

The Lower Granite, Little Goose, Lower Monumental, and Ice Harbor dams create a hostile gauntlet of deadly turbines and warm, stagnant reservoirs full of hungry predators that have caused dramatic declines in the Snake River’s salmon runs.

The system of dams and reservoirs kills 50 to 80 percent of juvenile salmon and steelhead as the fish make their way downstream to the ocean. Climate change is already affecting runoff patterns in the Columbia basin, causing mountain snow to melt earlier in the spring, which leads to lower summertime flows and higher summer water temperatures.

If the dams remain in place, global warming could push the Snake River’s remaining wild salmon runs to extinction. A free-flowing river, on the other hand, would allow salmon and steelhead quicker, safer access to high elevation habitat that is expected to remain hospitable for these fish even with substantial warming.

Dam removal

The best available science concludes that removing these outdated dams and restoring a free-flowing lower Snake River would allow for the restoration of healthy, fishable salmon and steelhead runs to the largest potential block of healthy salmon habitat remaining in the lower 48 states.

The Salmon River’s high elevation habitat is likely to continue to be productive even in the face of climate change, but only if impacts of the four lower Snake dams – which heat up and slow down the river and provide refuge for predator fish that eat young salmon – are significantly reduced.

Win-win solutions

Before removing the four lower Snake River dams, the services they provide must be replaced with cost effective alternatives.

The economic benefits of restoring the lower Snake River and its salmon and steelhead have been estimated in the hundreds of millions thanks to the income it would generate for commercial fishing up and down the Pacific Coast, increased recreational fishing from Astoria, OR to Stanley, ID, and new boating, camping, hiking, and hunting opportunities along the scenic lower Snake River.

Dam removal would also eliminate a growing flood risk in the town of Lewiston, Idaho, where sediment is piling up behind Lower Granite Dam, the uppermost of the four lower Snake River dams. If Lower Granite is not removed, Lewiston’s levees, along with the city’s railroad and highway bridges, will have to be raised substantially to protect the community from the ever-rising river. Raising the levees could cost taxpayers up to $87 million and would further wall the city off from its riverfront.

The benefits these dams now provide can be replaced by other means, while still allowing the Northwest to have affordable, carbon-free energy. The dams produce the least amount of energy when it’s needed the most: during the cold of winter and heat of summer when river flows are low. The energy from the dams can be replaced through a combination of cost-effective energy efficiency, wind power, and other clean energy sources.

The freight transportation benefits of the dams are also replaceable. Currently, a significant proportion of Northwest wheat farmers rely on Snake River barges to get their grain to market. Dam removal will require targeted upgrades to southeastern Washington’s rail, highway, and Columbia River barge systems. Only one of the four dams provides irrigation water, a small amouth that could continue to be accessed by extending pumps into the free-flowing river. Dam removal would also likely be cheaper in the long run for taxpayers and electricity ratepayers, as it would reduce mitigation costs for the rest of the Columbia River dams.

American Rivers is ready to evaluate and even embrace an alternative plan that achieves recovery of harvestable salmon and steelhead runs, but none has come to light so far, which is why we have found ourselves engaged in long running litigation. As other river and water management settlements around the West have demonstrated, it takes hard work to chart out a win-win solution, but such outcomes can be and have been achieved.

In the Columbia-Snake basin, a win-win solution will be one that restores abundant, harvestable wild salmon, fosters investment in new renewable energy, ensures sufficient water supplies and transportation infrastructure for farms and communities, and reduces risk of flood damage. Reaching this outcome will require strong leadership from the White House, Northwest governors, and the Northwest congressional delegation. These leaders should encourage and even demand that Columbia Basin stakeholders get together to forge a comprehensive plan to restore imperiled salmon and protect and enhance their region’s economy and quality of life.

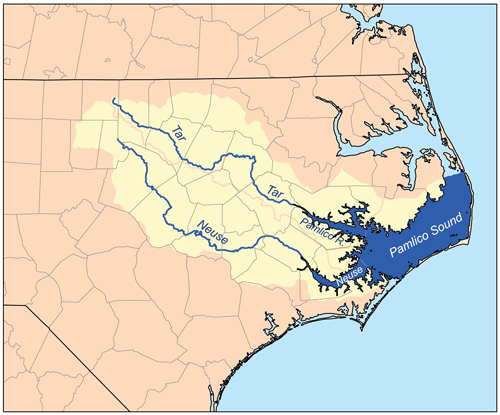

Neuse River

RIVER OF PEACE

The Neuse—derived from the Native American Neusiok tribe and translating to “peace”—is an excellent river to experience. Linking North Carolina’s original capital city of New Bern to its current capital of Raleigh, the Neuse River serves as a 250-mile connection between past and future—and the Piedmont and Pamlico Sound. A lot can happen over that kind of distance.

The action gets underway at the headwaters, where the dynamic community of Raleigh-Durham remains one of the fastest growing regions in the nation. Roughly 2.5 million people live within the river basin, most of them on this upper end. The Flat and Eno Rivers merge to form the Neuse River under Falls Lake Reservoir, Raleigh’s primary water supply, which spans more than 12,000 acres and also provides some structural flood control in the basin. The removal of the antiquated Milburnie Dam in the fall of 2017 allowed the unbridled river to glide from Falls Lake Reservoir all the way to the Atlantic, making it one of the longest free-flowing rivers in the Southeast.

The Neuse River Greenway Trail winds through wetlands on a boardwalk and courses alongside the river as Raleigh’s contribution to the state’s Mountains-to-Sea Trail that runs from the Great Smoky Mountains to the Outer Banks. In 2020 the Neuse River Blueway was launched creating a interconnected network of paddle and walking trails. About halfway between Raleigh and the river mouth, the Cliffs of the Neuse rise up as an impressive 100-foot canyon within the coastal plain at Seven Springs. Hiking trails at the surrounding state park explore the riverside habitats and their mature forests and lead to some quiet fishing spots along the waterway.

Did You know?

The Neuse is the longest river contained entirely within North Carolina.

The Neuse is considered one of the widest rivers in the U.S. Six nautical miles across at its widest point, it averages more than three miles in width between the Intracoastal Waterway and New Bern.

Established at the river mouth in 1710, New Bern is the first capitol of the state of North Carolina.

At an estimated 2 million years old, the Neuse is one of the oldest rivers in the U.S. Archeological evidence shows that humans settled around the Neuse some 14,000 years ago.

What states does the river cross?

North Carolina

The plot thickens near the mouth of the Neuse, where the river changes to slow-moving estuary habitat before joining the Tar and Pamlico Rivers in Pamlico Sound. Easily explored by kayak, canoe or SUP, the estuary is home to a wide variety of coastal game fish as well as birds, oysters, and countless other species. Dolphins and alligators are seen regularly in the estuary, and sharks and manatees occasionally appear as far upriver as New Bern, about 35 miles from the Atlantic.

The Neuse has an excellent striper run, and is home to several species of fish that split their time between the ocean and freshwater, like shad, herring, and American eel. Many endangered species including the Carolina madtom (a freshwater catfish), Tar River spinymussel, piping plover, dwarf wedge mussel, and loggerhead turtle remain in the Neuse River basin. The Neuse is also home to vital populations of blue crab and oysters.

The Backstory

The Neuse has suffered from municipal and agricultural pollution issues for decades now, prompting its listing as one of America’s Most Endangered Rivers® in 2007 after multiple nominations. Currently, the river is plagued by excessive nitrogen and phosphorous from agricultural-wastewater and polluted-stormwater runoff from urbanized and rural areas. The impacts of climate change have also led to extreme flooding events across the watershed.

On the main stem of the river, recurring algal blooms continue to show that the controls designed to reduce excessive pollution are not meeting the needs of a balanced ecosystem. The algae can produce toxins leading to some of the largest fish kills in the nation. An estimated 150,000 fish died as a result of a low oxygen “dead zone” in the Neuse River estuary over 10 days in July, 2015.

Falls Lake Reservoir has a major impact on the basin. While it has been very effective at flood control, it also separates the Neuse River from its floodplain, eliminating critical habitat, reducing water quality, and impairing the river’s ability to recover from increasing droughts and floods.

In the headwaters, the amount of water flowing in the tributaries to Falls Lake Reservoir has been declining for years due to development and land use conversion, droughts, and increased water demands. Only a small amount of the reservoir is dedicated to water supply, and there is a growing awareness that Raleigh’s reliance on Falls Lake Reservoir for a clean and abundant water supply into the future is in jeopardy. Raleigh Metro is already home to 1.3 million people and growing at a rate of 2.2 percent a year. North Carolina is expected to add more than 3 million people by 2029.

The reservoir is also impaired due to excessive nitrogen and phosphorous from failing wastewater treatment plants upstream and stormwater runoff from the surrounding urbanized and rural areas in Durham, Orange, Granville, and Person County. Many of the streams flowing into the reservoir have been impacted as well and need restoration to allow them to be an asset for the communities around them.

The Future

The Neuse’s free-flowing nature from Raleigh to the Atlantic provides great opportunities for communities around the river to embrace it as a recreational and economic resource. Of the 3.5 million acres that comprise the Neuse Basin, 48,000 acres are state parks, 110,000 acres are game lands held by the Wildlife Resources Commission, and 58,000 acres are National Forest.

But the issues surrounding water quality and the water supply in the Neuse need to be solved together. The Neuse River watershed is at the center of a tangle of federal, state, and local regulations and incentives, each designed to address a specific issue without taking into account the system as a whole and the interconnections that exist between having clean water and ensuring water supplies for people and nature. A new water management system needs to be developed that reduces the silos of management existing today and relies on natural infrastructure to restore the balance of the watershed. That involves updating the management of Falls Lake Reservoir in order to meet the needs of the growing population and working to restore the floodplain to reduce downstream pollution from agricultural operations.

The basin is losing crucial elements of its natural systems—healthy streams, wetlands, forests, and floodplains—that filter clean water and provide flood protection. Major developments proposed to accommodate the projected population increase of a million new residents in the Neuse River basin will magnify the issue if steps are not taken to balance the system. American Rivers’ long-term goal is to create a comprehensive water management system within the Neuse basin that provides reliable, sustainable clean-water supplies and recreational opportunities for growing urban and rural communities while protecting and restoring the ecology of the basin.