Connecticut River

NEW ENGLAND STRONG

New Englanders take great pride in the region’s longest river, and they should. Wild, natural scenery abounds along the 410-mile Connecticut River, which is heralded as the first—and only—National Blueway designated under the America’s Great Outdoors initiative by the Obama administration in 2012. The program was dismantled in 2014, but the national landmark that is the Connecticut River endures.

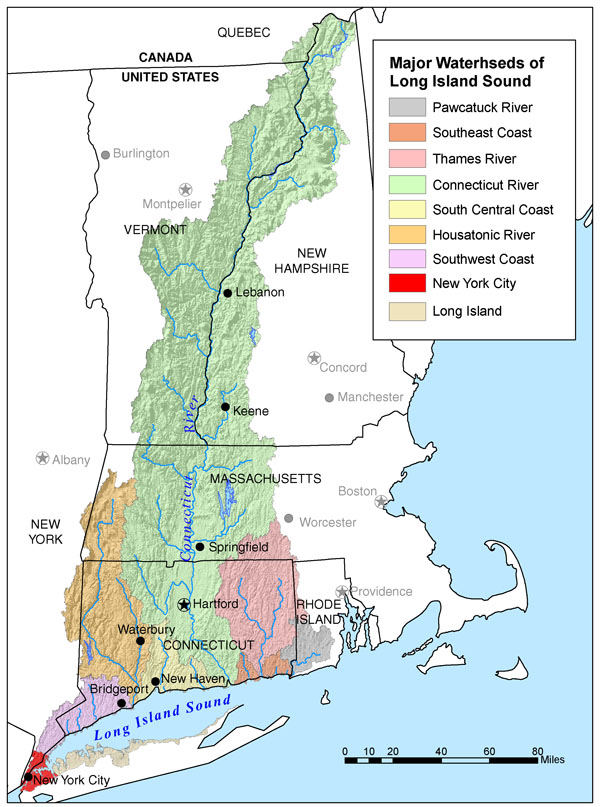

The river that flows from the Canadian border to the Long Island Sound in Connecticut didn’t always merit such lofty praise. Once described as America’s “best landscaped sewer,” the Connecticut has largely rebounded from hard times and today provides drinking water for millions and supports recreational uses, important fisheries, and healthy landscapes. The river and its tributaries have received several federal designations for their wild and scenic nature and importance to the region’s cultural heritage.

With a watershed that includes more than 2.4 million residents spread across some 400 communities, the Connecticut means much to many. Outstanding boating opportunities range from kayaking and quiet water boating on its more placid reaches to whitewater paddling on tributaries like the Deerfield, Farmington, and West rivers, extending downriver to heavy motor traffic between the town of Essex and the river mouth. Due to the heavy silt loads carried by the river that obstruct ship navigation, the Connecticut is one of the few major rivers in the United States without a major city at its mouth. Its largest cities—Hartford and Springfield—lie 45 and 69 miles upriver, respectively.

Abundant cold-water habitat throughout the watershed provides great opportunities for fishing, and several species of fish—both resident and migratory—can be found, including brook trout, winter flounder, blueback herring, alewife, rainbow trout, large brown trout, American shad, hickory shad, smallmouth bass, Atlantic sturgeon, and striped bass. After an absence of more than 200 years, Atlantic salmon have been reintroduced to the Connecticut by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Meanwhile, lake trout and landlocked salmon reside in the upper river surrounding the Connecticut Lakes.

The Silvio O. Conte National Fish and Wildlife Refuge serves as a cornerstone of the fishery and surrounding ecosystem since 1997. Located within parts of four New England states—New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, and Connecticut—the 36,000-acre refuge, named for its championing Congressman, is the only refuge of its kind to encompass an entire watershed. Its creators recognized the need to protect the whole river system and its wide variety of unique habitats ranging from northern forest to salt marshes in order to protect migratory fish and other species dependent upon the Connecticut River corridor.

Did You know?

The Connecticut River was designated the first National Blueway under the America’s Great Outdoors Initiative by the Obama administration in 2012.

As testament to its watershed-wide mission, the Silvio O. Conte National Fish and Wildlife Refuge is one of only three refuges in the National Wildlife Refuge System that has “Fish” in its title.

In 1997, the Connecticut River was designated one of only 14 American Heritage Rivers in recognition of its “distinctive natural, economic, agricultural, scenic, historic, cultural, and recreational qualities.”

WHAT STATES DOES THE RIVER CROSS?

Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Vermont

The Backstory

The history of the Connecticut River can be told through dams. New England communities were built along the banks of rivers and dams have been a central component since the beginning to provide water for irrigation, power generation, industrial operations, and drinking. The Connecticut remains among the most extensively dammed rivers in the nation.

Let's stay in touch!

We’re hard at work in the Northeast for rivers and clean water. Sign up to get the most important news affecting your water and rivers delivered right to your inbox.

Many of those dams are now obsolete. Yet more than 3,000 of these obstructions still impound the tributaries of the Connecticut River, with adverse impacts on river health, flooding, local economies, and community quality of life. The river’s great anadromous fish runs have suffered extensively through years of obstruction and warm-water discharges extending for miles below the Vermont Yankee Nuclear Power Plant in Vernon, VT. Downstream in South Hadley Falls, MA, American shad declined by 80 percent between 1992 and 2005, as measured at the Holyoke Dam.

Road-stream crossings are another longstanding challenge within the watershed, which contains more than 44,000 crossings. Many are undersized relative to stream size. Ideally, each crossing would mimic the natural stream banks and allow fish and wildlife to pass under while cars and travelers pass safely over. But the Connecticut’s undersized crossings are easily obstructed and prone to failure during large storms such as Tropical Storm Irene in 2011, when over 1,000 culverts and 500 bridges failed.

What’s New

Update on the Washburn Dam Removal Project

Congratulations to the whole American Rivers project team and partners! The Washburn Dam removal on the Mohawk River near Colebrook, NH, was completed in October 2024, marking a conservation milestone in the upper Connecticut River watershed. This high-priority dam removal reconnected 33 miles of high-quality habitat critical for native species, particularly wild brook trout, which rely on free-flowing rivers for migration and reproduction.

Demolition and the related channel and riverbank restoration work began in June 2024, with crews navigating various challenges. Record-high flood events and nonstop rain throughout much of the early stage required our contractor to repeatedly adjust work strategies. Our partners handled these challenges gracefully and managed to get the work done just a few weeks after the expected completion date.

American Rivers worked with several partners on the project, including NH Fish and Game, NH Department of Environmental Services, Interfluve, SumCo, Headwaters Consulting, LLC, and landowners and neighbors. Funding was provided by USFWS, NH Fish & Game, the Davis Conservation Fund, and the NH Charitable Foundation Mitigation and Enhancement Fund.

Special shout out to our newest Northeast team member, Sarah Lillie, for managing her first dam removal project! Amy Singler (now on a work detail with USFWS) was the spark plug that got the project off the ground and helped Sarah take the reins in March. It was a great way for Sarah to dip her toes before jumping into several upcoming removal projects across the Northeast!

American Rivers works hard to ensure that hydropower dams balance energy production and improve river health. There are five hydropower dams owned by FirstLight and Great River Hydro that are being relicensed for the next 40-50 years. These five dams dramatically impact the health of over 200 miles of the Connecticut River. We are actively working with state and federal agencies and our partners to ensure that these projects better support fish passage, river health, and better recreation infrastructure.

The Future

The Connecticut River has come a long way, but there are plenty more opportunities to improve river access for recreation, river connectivity, habitat restoration, and flows at the large hydro facilities throughout the corridor.

The river could soon flow at a more natural pace, should the computer-modeling efforts of scientists at the University of Massachusetts to coordinate water releases between the river’s 54 largest dams pay off. With the addition of fish ladders at multiple dams on the river, access to historic spawning habitat for anadromous fish is returning as well

Like much of New England, the watershed has more forested land today than it did 150 years ago. Combined with the cultural and recreational value of the river system, that natural landscape has helped major tributaries like the Eight Mile River, Farmington River, and Westfield River earn Wild and Scenic River designation, with potential for more on the horizon.

Building off the federal Connecticut River Blueway Designation, American Rivers is continuing to bring expertise in developing river recreation and protection opportunities to the watershed to engage with partners and help direct funding for these efforts.