Rivers and their restoration are complex, and any effort to rehabilitate a river system needs to be based on a sound understanding of the ecological benefits and drawbacks of a proposed restoration plan.

Over the past three decades, the scientific community has advanced our understanding of rivers and helped us to realize the significant negative impacts that dams have on river systems. Dams disrupt a river’s natural course and flow, alter water temperatures in the stream, redirect river channels, transform floodplains, and disrupt river continuity. These dramatic changes often reduce and transform the biological make-up of rivers, isolating populations of fish and wildlife and their habitats within a river.

While there is a need for more specialized research on the ecological impacts of dams and dam removal, several studies indicate that dam removal can be a highly effective river restoration tool to reverse these impacts and restore rivers. Angela T. Bednarek, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Pennsylvania recently conducted a comprehensive review of the short- and long-term ecological impacts of dam removal. Bednarek conducted a literature search to identify and review all available published (and many unpublished) studies on dam removal to determine if and how dam removal can be effective in improving water quality and restoring fish and wildlife habitat in and around a river. Her study focused on numerous ecological measures that are critical to assessing the positive and negative impacts of dam removal both from short- and longterm perspectives, including:

- Flow;

- Shift from reservoir to free-flowing river;

- Water quality (e.g., temperature and supersaturation);

- Sediment release and transport; and

- Connectivity (e.g., migration of fish and other organisms).

While there are some limited short-term ecological consequences of dam removal, Bednarek’s study found that the long-term ecological benefits of dam removal—as measured in improved water quality, sediment transport, and native resident and migratory species recovery — demonstrates that dam removal can be an effective long-term river restoration tool.

This paper summarizes Bednarek’s findings and comments on Bednarek’s call for additional research to further the scientific community’s knowledge of the ecological impacts of dam removal. The paper is organized into five sections: (1) reestablishment of a natural flow regime; (2) transformation from reservoir to river system; (3) change in river temperatures and oxygen levels; (4) sediment release and transport; and (5) migration of fish and other organisms. Bednarek’s paper was published in the journal, Environmental Management, in spring 2001 (Bednarek, Angela. 2001. “Undamming Rivers: A Review of the Ecological Impacts of Dam Removal.” Environmental Management 27(6):803-814.). To obtain a copy, please contact the Rivers Unplugged campaign at American Rivers by calling (202) 347-7550.

Our nation’s network of rivers, lakes, and streams originates from a myriad of small streams and wetlands, many so small they do not appear on any map. Yet these headwater streams and wetlands exert critical influences on the character and quality of downstream waters. The natural processes that occur in such headwater systems benefit humans by mitigating flooding, maintaining water quality and quantity, recycling nutrients, and providing habitat for plants and animals. This paper summarizes the scientific basis for understanding that the health and productivity of rivers and lakes depends upon intact small streams and wetlands. Since the initial publication of this document in 2003, scientific support for the importance of small streams and wetlands has only increased.

Both new research findings and special issues of peer reviewed scientific journals have further established the connections between headwater streams and wetlands and downstream ecosystems. Selected references are provided at the end of the document.

Historically, federal agencies, in their regulations, have interpreted the protections of the Clean Water Act to broadly cover waters of the United States, including many small streams and wetlands. Despite this, many of these ecosystems have been destroyed by agriculture, mining, development, and other human activities. Since 2001, court rulings and administrative actions have called into question the extent to which small streams and wetlands remain under the protection of the Clean Water Act. Federal agencies, Congress, and the Supreme Court have all weighed in on this issue. Most recently, the Supreme Court issued a confusing and fractured opinion that leaves small streams and wetlands vulnerable to pollution and destruction.

We know from local/regional studies that small, or headwater, streams make up at least 80 percent of the nation’s stream network. However, scientists’ abilities to extend these local and regional studies to provide a national perspective are hindered by the absence of a comprehensive database that catalogs the full extent of streams in the United States. The topographic maps most commonly used to trace stream networks do not show most of the nation’s headwater streams and wetlands. Thus, such maps do not provide detailed enough information to serve as a basis for stream protection and management.

Scientists often refer to the benefits humans receive from the natural functioning of ecosystems as ecosystem services. The special physical and biological characteristics of intact small streams and wetlands provide natural flood control, recharge groundwater, trap sediments and pollution from fertilizers, recycle nutrients, create and maintain biological diversity, and sustain the biological productivity of downstream rivers, lakes, and estuaries. These ecosystem services are provided by seasonal as well as perennial streams and wetlands. Even when such systems have no visible overland connections to the stream network, small streams and wetlands are usually linked to the larger network through groundwater.

Small streams and wetlands offer an enormous array of habitats for plant, animal, and microbial life. Such small freshwater systems provide shelter, food, protection from predators, spawning sites and nursery areas, and travel corridors through the landscape. Many species depend on small streams and wetlands at some point in their life history. A recent literature review documents the significant contribution of headwater streams to biodiversity of entire river networks, showing that small headwater streams that do not appear on most maps support over 290 taxa, some of which are unique to headwaters. As an example, headwater streams are vital for maintaining many of America’s fish species, including trout and salmon. Both perennial and seasonal streams and wetlands provide valuable habitat. Headwater streams and wetlands also provide a rich resource base that contributes to the productivity of both local food webs and those farther downstream. However, the unique and diverse biota of headwater systems is increasingly imperiled. Human-induced changes to such waters, including filling streams and wetlands, water pollution, and the introduction of exotic species can diminish the biological diversity of such small freshwater systems, thereby also affecting downstream rivers and streams.

Because small streams and wetlands are the source of the nation’s fresh waters, changes that degrade these headwater systems affect streams, lakes, and rivers downstream. Land-use changes in the vicinity of small streams and wetlands can impair the natural functions of such headwater systems. Changes in surrounding vegetation, development that paves and hardens soil surfaces, and the total elimination of some small streams reduces the amount of rainwater, runoff, and snowmelt the stream network can absorb before flooding.

The increased volume of water in small streams scours stream channels, changing them in a way that promotes further flooding. Such altered channels have bigger and more frequent floods. The altered channels are also less effective at recharging groundwater, trapping sediment, and recycling nutrients. As a result, downstream lakes and rivers have poorer water quality, less reliable water flows, and less diverse aquatic life. Algal blooms and fish kills can become more common, causing problems for commercial and sport fisheries. Recreational uses may be compromised. In addition, the excess sediment can be costly, requiring additional dredging to clear navigational channels and harbors and increasing water filtration costs for municipalities and industry.

The natural processes that occur in small streams and wetlands provide Americans with a host of benefits, including flood control, adequate high quality water, and habitat for a variety of plants and animals.

Stormwater runoff is a major problem for watersheds across the country, particularly the Chesapeake Bay. Green infrastructure is being used as a tool to mitigate stormwater runoff by restoring natural ground cover which allows precipitation to infiltrate into the soil. Urban agriculture is an innovative green infrastructure practice because it provides many benefits to the community as well as to watersheds. Urban farms mitigate stormwater runoff, increase the nutritional health of communities, improve the local economy, and provide residents with greenspace.

Cities across the country, especially in the Chesapeake Bay watershed, should integrate urban agriculture into their planning materials and zoning codes in order to promote this all around beneficial green infrastructure tool. Our report discusses the importance of urban agriculture to cities and their watersheds as well as gives recommendations to city officials on how to promote the use of urban agriculture in their community.

Check out these links to learn more about urban agriculture:

- modernfarmer.com

- greenroofs.com

- greenroofs.org

- seedstock.com

- urbanfarmonline.com

- urbanfarming.org

- growingpower.org

- beginningfarmers.org/urban-farming

American Rivers’ 2014 Upper Flint River Resiliency Action Plan aims to guide work by a variety of stakeholders to restore drought resilience to the upper Flint River system of west-central Georgia. It follows on discussions and efforts of the Upper Flint River Working Group and on the RUNNING DRY report which we published with Flint Riverkeeper in 2013. Designed to be a “living document,” the Action Plan charts a plan of work that will be updated and expanded in future years as collaborative efforts in the river basin progress.

This action plan seeks to outline specific strategies to restore resilience to some of the most stressed portions of the river basin, along with highlighting key needs in the areas of policy, research and information. It includes a focus on preserving existing natural resources of value in the basin. This plan charts collaborative, transparent and practical efforts by the full range of individuals, communities, businesses, organizations and public entities that have a stake in the long-term health of the upper Flint River. In this spirit, this resiliency action plan serves as a starting point for collaborative work toward an integrated, basin-scale, science-based and practical approach to restoration throughout the upper Flint River basin.

Communities across the country are struggling to deal with the rising costs of controlling stormwater runoff and sewer overflows. Crumbling infrastructure and the expansion of hard surfaces such as pavement and roofs are sending polluted stormwater and sewage into surrounding waterways with increasing frequency. A changing climate defined by more severe storms will only increase this burden.

In the face of these challenges, many communities are embracing a new approach to managing runoff that focuses on capturing rainfall and preventing it from polluting surrounding waterways. By using green infrastructure techniques such as green roofs, rain gardens, tree planting, and permeable pavement, they are managing stormwater problems at a lower cost and realizing a wide range of other benefits from reduced air pollution, energy use, and urban heat island effect to improved wildlife habitat and aesthetics. These techniques also provide defenses against more frequent and severe heat waves, droughts, and flooding that a changing climate is bringing to many urban areas. Green infrastructure is a powerful tool for managing existing problems and preparing for the future.

A Challenge To Green Infrastructure Implementation

The Value of Green Infrastructure helps municipalities overcome a key barrier to more widespread adoption of green infrastructure. Our failure to value the full range of benefits from green infrastructure and the difficult challenge to translate these benefits into dollar figures so they can be compared to alternatives is restricting comprehensive integration of green infrastructure into local water management. And, determining the value of green infrastructure benefits for a locality has required studies beyond the resource capacity of most localities.

Evaluating The Benefits Of Green Infrastructure In Your Community

The guide produced by the Center for Neighborhood Technology and American Rivers, provides a framework that allows local communities to assess the local benefits of green infrastructure. The guidebook outlines a methodology for measuring and valuing the improvements in air quality, energy savings, carbon sequestration, and other areas. These benefits are above and beyond the stormwater control benefits, which are assumed to be equal to a similar investment in gray infrastructure. This guide allows communities to make more educated investments in infrastructure by helping them evaluate the full range of benefits from sustainable approaches to water management and realize green infrastructure’s potential to make communities more livable and less vulnerable to climate change.

staying green

Without proper maintenance, any type of infrastructure can lose functionality and ultimately fail. As more communities move towards adopting green infrastructure as a cost-effective approach to manage polluted runoff, it is critical that local governments address barriers to operations and maintenance. Despite the benefits of green infrastructure, operations and maintenance has been repeatedly raised as a technical barrier to adoption of green infrastructure and remains a concern for many local governments in the Chesapeake Bay region and across the country.

American Rivers and Green for All collaborated to develop two companion reports exploring different elements of operations and maintenance of green infrastructure in the region. The Staying Green: Strategies to Improve Operations and Maintenance of Green Infrastructure in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed report highlights existing information related to costs of green infrastructure maintenance, identifies the significant barriers to effective operations and maintenance of these practices, recommends strategies to improve operations and maintenance, and provides resources and case studies that local governments can use as models.

STAYING GREEN AND GROWING JOBS

Our companion report, Staying Green and Growing Jobs: Green Infrastructure Operations and Maintenance as Career Pathway Stepping Stones, assesses existing and potential occupations in green infrastructure operations and maintenance, highlights existing workforce development programs that can provide models for local governments or community organizations, and recommends strategies to improve career opportunities and job quality in the field of green infrastructure operations and maintenance.

The upper Flint River of west-central Georgia is a river running dry. While rivers and streams in arid parts of the United States often dry up seasonally, the Southeast has historically been known as a water-rich area with plentiful rainfall, lush landscapes, and perennial streams and rivers. The upper Flint River supports recreation, fisheries, local economies, and threatened and endangered species that all depend on healthy and reliable flows which are becoming increasingly rare.

Examining and addressing low-flow problems in the upper Flint River basin is important for the entire Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint river basin. The Flint also offers examples of what can and likely will happen to more rivers in urbanizing areas and in historically wet regions facing increasing water quantity stress.

What’s wrong in the upper Flint? Recent droughts have reduced popular sections of the river to wide expanses of exposed rock with trickles of water running in between. And, in most summers the river runs lower, and for longer, than it did in the past.

This report seeks to bring greater awareness and understanding to the upper Flint’s low-flow problems, to point the way toward solutions, and to begin productive dialog among all stakeholders in a healthy upper Flint River.

These low-flow problems cannot be attributed to any single factor, but rather to many factors which have come into play over a period of decades. Among these factors are:

- Urbanization and land use change;

- Increased frequency of drought;

- An increase in ponds, lakes and reservoirs of all sizes throughout the tributary stream network;

- Increasing demand on the river system for public water supply; and

- A lack of direct return flows of water withdrawn from the river system.

When droughts arrive, the river has lost its resilience against damaging low flows due to the various different demands on its water. In other words, it is now more vulnerable and delicate in the face of chronically dry weather conditions.

Healthy flows can be restored in the upper Flint River basin, but it will take time and a broad group of stakeholders to leverage such a change. Given the wide range of factors that have led to the upper Flint’s low-flow problems, flow restoration opportunities include the following:

- Expand on the recent work by water providers to find areas of water loss in their systems and implement programs to eliminate leaks;

- Improve water efficiency and conservation, especially with regard to outdoor irrigation in the summer months;

- Employ green stormwater infrastructure to infiltrate more rainwater and restore the natural water cycle;

- Increase the volume of return flows to the river system;

- Explore more potable water reuse in the basin;

- Manage existing reservoirs to better ensure healthy flows downstream.

Taking steps to restore healthy flows can reduce the stress on the river system and enable it to regain some of its natural resilience, better preparing the river for droughts to come and protecting the river for the benefit of communities today and for future generations.

Learn more about the Upper Flint River Working Group and the plans to address these issues through the Upper Flint River Resiliency Action Plan.

In this report, Ceres and American Rivers join forces to highlight a range of innovative approaches to creating sustainable financing for our communities’ water systems. The report discusses specific actions that environmentalists, economists, water utilities, water users, financial institutions, foundations, investors and labor groups to create opportunities can adopt to improve predictable, secure revenue streams, leverage funding and financing options, and create partnerships to build and operate water infrastructure.

This report originates from a convening of water providers, finance experts and NGOs in August 2011, as part of The Johnson Foundation’s Charting New Waters. With support from the Russell Family Foundation, Ceres and American Rivers were able to continue that dialogue in a series of interviews. This document is an attempt to distill those ideas into a set of high‐priority, high‐impact strategies that can be jointly pursued by the many stakeholders who have a stake in shaping a more resilient water future.

Like many sources of water pollution, stormwater generally falls under the prohibitions and requirements created by the federal Clean Water Act. For over a dozen years, these requirement have found their way into permits for municipal storm sewer systems. Unfortunately, these permits have not done enough to stem the flow of stormwater pollutants into our urban waters. Truly protecting, and restoring, our waters will require a different approach to stormwater permits, one that emphasizes building homes, businesses, and communities in ways that reduce the amount of stormwater running off of parking lots, streets and rooftops.

This guide is intended to be a resource for community and watershed advocates that provides clear examples of new stormwater permits that encourage or require “low impact development” or “green infrastructure.” These permits represent an emerging new generation of regulatory approaches and reflect the emerging expertise of water advocacy organizations, stormwater professionals and permitting agencies. Our goal is to provide information about new trends in stormwater permitting and examples of permits that demonstrate leadership toward standards that will build green infrastructure and compliance with water quality standards. With this tool, we hope to inform and inspire continued progress toward stormwater permitting and management that protects our rivers and other shared waters, invigorates healthy communities, and provides cost-effective solutions for stormwater managers.

The guide is organized as a matrix that combines model permit language along with excerpts from comment letters that have helped to drive this evolution. The concerns raised by watershed advocates, and the support they often provide to state permit agencies, frequently have been instrumental in shaping better stormwater permits. We hope that providing examples of the expertise shown by both communities that we can inform a broader movement toward better control of urban stormwater.

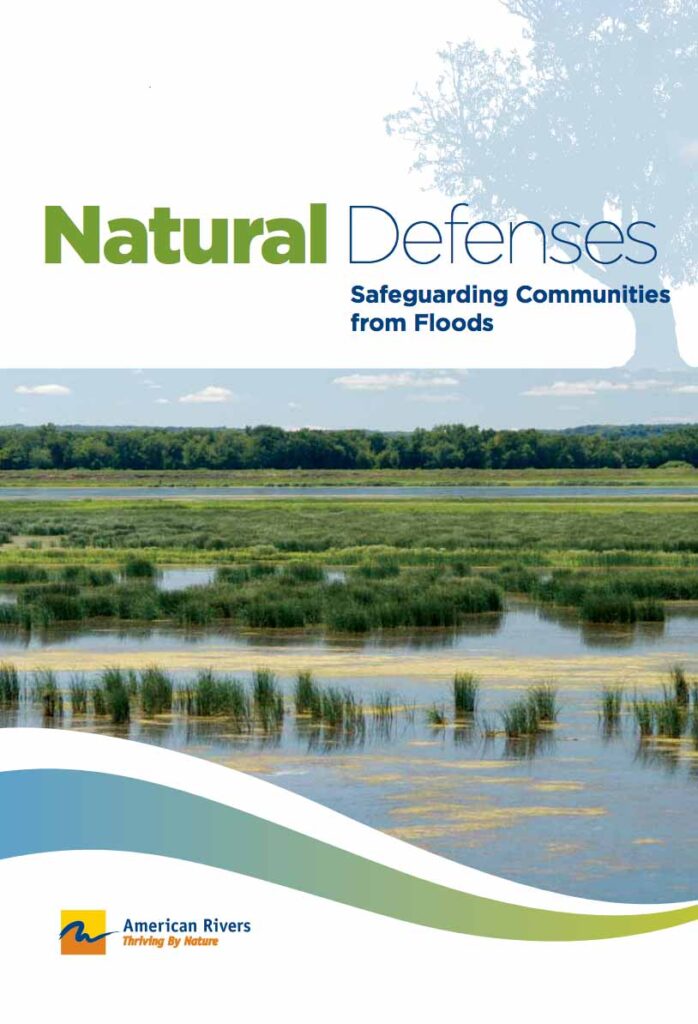

INCREASING FLOOD RISK IN A CHANGING CLIMATE

The impacts of our changing climate are becoming more apparent every day. In the first decade of the new millennium, extreme rainfall events, combined with changes in land use, have resulted in an increase in flood events and in an increase in annual flood losses from $6 billion to $15 billion despite the billions of dollars invested in flood control.

As the climate changes, bringing more frequentn and intense storms and floods, communities living near streams and rivers and on our coasts are facing increasing threats. Lives and property are increasingly at risk, flood damages are straining tax-payer dollars, and clean water and wildlife habitat are suffering. Our changing climate, outdated management approaches and policies, underfunded and under utilized green infrastructure, and increasing urbanization are causing a flood management crisis for federal agencies and communities alike.

Traditional Gray Infrastructure Will Continue To Place People In Harm’s Way

Our country is struggling to break out of a long-standing negative feedback loop. Gray infrastructure such as dams, levees and concrete flood control channels, incentivizes people to live in harm’s way. Living in harm’s way creates a perceived need for more gray infrastructure that ultimately makes flooding worse, passes the problems downstream, disrupts natural river processes, and perpetuates a flood-damage-repair cycle that has devastating costs to life, property, taxpayers, and the environment.

Securing reliable supplies of clean water for today and the future is a critical concern for communities across the country, and particularly in the Southeast, where communities are grappling with water scarcity issues more than ever before.

This report documents the financial risks and water resource risks tied to the development of new water supply reservoirs in the Southeast. It comes as many local governments throughout Georgia, the Carolinas and neighboring states are considering significant spending of public taxpayer and ratepayer dollars to build new water supply reservoirs.

Georgia reservoir proposals on the drawing board, for example, could total $10 billion in taxpayer and ratepayer dollars. The report also shines a light on recent water supply reservoir projects that provide cautionary tales of communities burdened by expense and debt.

The report outlines the following financial and resource risks inherent in the pursuit of new water supply from reservoirs:

- Reservoirs are highly expensive, racking up debt for ratepayers and taxpayers.

- A reservoir’s price tag is typically a moving target.

- Reservoir financing plans often rely on inflated population growth projections, ultimately leaving existing residents holding the bag.

- In order to remain full, a reservoir depends on increasingly uncertain rainfall. And, a reservoir loses water when high temperatures cause evaporation.

- Reservoir water is a contested resource subject to competing demands in the river system.

The report also offers five key recommendations for local leaders who seek to reduce their communities’ risks—both financial risks and closely linked water resource risks—in planning for enough clean water for the future:

- Optimize existing water infrastructure first.

- Plan for water use to decrease as a community grows.

- Pursue flexible water supply solutions, like efficiency measures.

- Demand accurate assessments of costs.

- Examine water availability to minimize resource risks.

As communities endeavor to find ways to secure water supplies, it is critical that decision-making add to a community’s flexibility and resilience. The high-price, high-risk water supply reservoir strategy can leave a community financially vulnerable, tying up assets and leaving taxpayers and ratepayers on the hook without a guarantee that the water will be there when they need it.

There is a more prudent and proven path to providing water supply and ensuring flexibility for the future, one rooted in stewardship of public dollars and natural resources both. As Southeastern communities move forward to develop strategies to meet tomorrow’s needs, the communities that choose a prudent path will be better positioned—from both a financial and water resource perspective—to address the needs of today and the future.

The Southeast United States faces unprecedented challenges to its water supply. Growing populations and the impacts of climate change are putting new strains on communities and their rivers. Our local leaders are facing the pressing question of how to ensure a clean, reliable water supply for current and future generations.

Traditionally, building more dams and reservoirs was the first and only answer to water supply problems. But these 19th century approaches should not be the primary solutions for our new 21st century challenges. They don’t address the root problem — water is finite and we are not using the water we do have wisely. Relying solely on building large new dams is not costeffective and it won’t solve today’s water needs. Per gallon, dams cost up to 8500 times more than water efficiency investments. Dams are fixed in one place and hold a limited amount of water. Even when we do get sufficient rains to fill reservoirs, these giant pools can lose tremendous amounts of water through evaporation.

For these reasons, building new dams should be the absolute last alternative for solving our water supply needs. Hidden Reservoir makes the case that water efficiency is our best source of affordable water and must be the backbone of water supply planning. By implementing the nine water efficiency policies outlined in this report, communities across the Southeast can secure cost-effective and timely water supply.