The majestic Colorado River cuts a 1,450-mile path through the American West before drying up well short of its natural finish line at the Gulf of California. Reservoirs once filled to the brim from the river and its tributaries are at historic lows due to an unprecedented drought and growing human demands. Diminished stream flows now pose serious challenges for wildlife and recreation, as well as cities, farms, and others who rely upon the river. Steps currently being taken to improve the situation are not up to the task of bringing the river system back into balance and providing a reliable water supply for all the communities who depend upon the Colorado River.

Fortunately, we have five feasible, affordable, common-sense solutions that can be implemented now to protect the flow of the river, ensure greater economic vitality, and secure water resources for millions of Americans.

- Municipal conservation, saving 1 million acre-feet

- Municipal reuse, saving 1.2 million acre-feet

- Agricultural efficiency and water banking, saving 1 million acrefeet

- Clean, water-efficient energy supplies, saving 160 thousand acrefeet

- Innovative water opportunities, generating up to 1 million acrefeet

Proven Solutions, Progress We Can See

Federal, state and local officials can help make most these changes today, and start reaping many benefits within a year or two. A few solutions will require longer-term collaboration among governments and users, sometimes a rarity in today’s national political and economic climates. Yet, Colorado River basin states and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation have a solid record of increased cooperation over the last two decades. What’s more, many basin states are already taking steps to update their state water plans with innovative, creative ideas for improving water management. The common-sense and money-saving approaches outlined here are the best path forward. We’ve already seen strong progress; dozens of successful programs have already been implemented. From citywide conservation efforts to innovative rainwater capture, to successful and mutually beneficial agricultural solutions, we know these work. What’s more, we know they are the most efficient, cost-effective, widely available steps we can take right now to solve our supply/demand gap on the Colorado River without doing any harm, while continuing to grow our western economy.

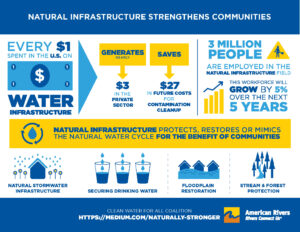

Communities in the United States are being threatened by sewage overflows, flooding, polluted stormwater, leaky pipes, and at-risk water supplies. These threats are a result of our nation’s outdated water infrastructure and water management strategies, and their impacts fall disproportionately on low-wealth neighborhoods and communities of color that are already suffering from a lack of investment and opportunity. To solve this problem, we do not just need more investment in water infrastructure. We need a new kind of water infrastructure and management, and we need it in the right places. The solution is the equitable investment in and implementation of natural infrastructure. Naturally Stronger makes the case that if natural infrastructure is used in a more integrated water system, we can transform and restore our environment, invigorate the economy, and confront some of our country’s most persistent inequities.

Bringing Federal Policy into the 21st Century

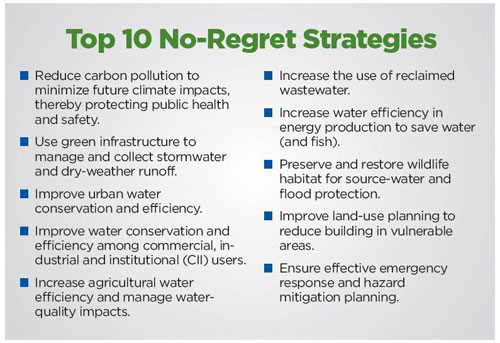

Many federal policies still encourage the same backward-looking water management approaches that didn’t work in the past and are even less suited to the future. Federal funding and policies reward wasteful water use and support destructive, inflexible infrastructure projects, while important programs that would help save water or preserve valuable wetlands and floodplains fall woefully short of what is needed. There is a widespread failure to plan for and address the changing conditions we know are coming. Too many federal policies are moving us in the wrong direction and making communities and wildlife more vulnerable.

The following ten reforms are some of the best ways we can change outdated federal policies and embrace a forward-looking approach to water management. They represent proactive steps Congress and the Executive Branch can take to address climate change.

- National Flood Insurance Program: Change flood insurance rates and maps to ensure they reflect risk and discourage construction and reconstruction in vulnerable areas

- Farm Policy: Reward farmers for being responsible stewards of land and water resources and encourage better flood management practices on agricultural lands

- Bureau of Reclamation: Develop comprehensive water management plans for Reclamation projects to create greater flexibility and improve the health of rivers

- Energy Policy: Integrate water management and energy planning and ensure that energy and water are being used as efficiently as possible

- Clean Water Act: Restore protections to wetlands and streams and improve implementation and enforcement of protections for all waters

- Water Resources Development Policy: Reform the principles that guide construction of federal water infrastructure projects to minimize damages to rivers, wetlands, and floodplains and prioritize more cost-effective, flexible projects

- Clean Water and Drinking Water Infrastructure Funding: Reform funding criteria to ensure that funded projects embrace green infrastructure and can adapt to changing conditions

- National Forest Management: Diversify Forest Service management practices to prioritize effective water management

- Transportation Policy: Ensure that funded projects minimize impacts on surrounding water resources and wildlife populations

- Wildlife Management: Better coordinate federal actions and invest in climate change planning to help maintain healthy fish and wildlife populations

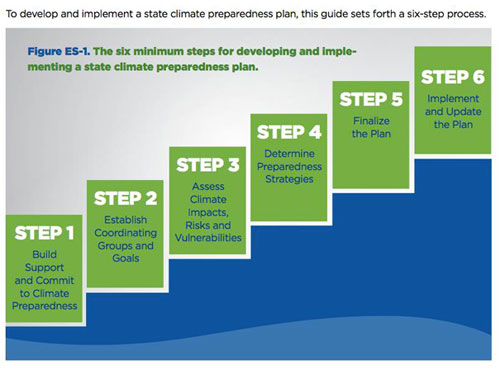

A Water Preparedness Guide for State Action

In recent years, a record number of extreme weather events including floods, heat waves, droughts, fires and snowstorms have wreaked havoc in the United States. As carbon pollution continues to warm the planet and fuel extreme weather, it is critical that states begin planning for a new “normal.”

This guide provides information for state governments, water managers, and other stakeholders to use in preparing for the consequences of hotter temperatures, more variable and volatile precipitation events, and rising seas. By undertaking climate preparedness planning, states can better manage the impacts of climate change and protect the well-being of residents, communities, the economy and natural resources.

Fourteen different extreme weather events, including widespread drought and massive flooding, each caused damage of more than $1 billion in 2011. In 2012, scorching heat brought drought conditions to more than 65 percent of the country and contributed to large wildfire outbreaks in the West that burned more than 9.2 million acres. Severe storms and tornadoes also ravaged large swaths of the country. Additionally, in late October 2012, Superstorm Sandy devastated communities along the northeastern seaboard with record-breaking storm surges and historic flooding. In total, 11 extreme weather events in 2012 had costs exceeding $1 billion each. Moreover, 2012 was the hottest year since record-keeping began in the U.S. in 1895, As climate change increasingly fuels extreme weather, this trend of more extreme and record-breaking climate events shows no signs of abating.

Many extreme weather events as well as warmer temperatures, changing precipitation patterns and rising sea levels are expected to intensify as climate change continues. These deviations from historical climatic norms are affecting our communities and natural resources by threatening public health, affecting water availability and quality and energy production, placing vulnerable homes and infrastructure at risk, and jeopardizing vital ecosystems and habitats.

To address these challenges, more than 35 states have conducted planning to reduce the carbon pollution that contributes to climate change. Despite these efforts, however, states already are experiencing the impacts of climate change and will need to plan and prepare for the wide-ranging consequences of increasingly warmer temperatures, variable precipitation patterns and higher seas. To date, only 10 states have developed comprehensive plans to prepare for these climate-related impacts. Remarkably, most other states are not planning and remain ill-prepared for the challenges of climate change both now and in the years ahead.

States can use the six-step process in this guide to comprehensively plan and prepare for the water-related impacts of climate change. Although this guide focuses exclusively on climate impacts related to water, non-water impacts also will have wide-ranging ramifications for people, communities and ecosystems and must also be considered in climate preparedness planning.

Climate impacts will vary by region, and the strategies and resources available to manage these impacts will be shaped and limited by existing state laws, policies and resources. Accordingly, the process for developing a state climate preparedness plan contained in this guide is divided into three different tracks: Basic, Moderate and Robust. States can follow a single track throughout the planning process or choose to follow different tracks for each step. Additionally, specific examples are included to illustrate how some states have conducted their planning process. The most important message is that all states must start the planning process now. The signs of a changing climate are already being seen, and continued delay and inaction will only magnify the impacts and the cost of addressing them.

The Bay Delta Conservation Plan (BDCP) is more than 15,000 pages long and covers a wide range of issues ranging from water supply, new facility construction, aquatic and terrestrial ecosystem management, governance and costs. Few outside of the handful of people deeply involved in BDCP actually know what is in the document due to its imposing size. This is particularly true for the various stakeholder groups who lack either the staff or the technical capacity to review the document and to evaluate the complex analyses that underpin it.

Saracino & Mount, LLC, was asked to assemble a panel of independent experts to review portions of the Plan to help guide decision making by two non governmental organizations: The Nature Conservancy and American Rivers. Guided by a narrow set of questions about how the Plan would impact water supply and endangered fishes, the panel reviewed the Plan documents and conducted analyses of data provided by the project consultants. The following document is a summary of our results.

Across the country, communities are struggling with how to fix and replace failing and outdated infrastructure and meet new demand to manage stormwater and protect clean water. American Rivers worked with the American Society of Landscape Architects, ECONorthwest, and the Water Environment Federation to release the “BANKING ON GREEN” report to build on the current understanding of the cost-effectiveness of green infrastructure and examine how these practices can increase energy efficiency and reduce energy costs, reduce localized flooding, and protect public health.

When rainwater hits hard surfaces like roads and parking lots, it can’t soak into the ground and instead runs along the surface until it flows into a storm drain or into a local river or stream. Known as stormwater runoff, this water can pick up pollutants such as heavy metals, brake linings, and deicing salts which contaminate local waters. Additionally, high volumes of stormwater can exacerbate localized flooding posing a threat to public health and safety. In older urban areas with combined sewer systems, high volumes of stormwater runoff can overwhelm the capacity of the system and result in combined sewer overflows (CSOs) which send untreated sewage and stormwater into rivers and streams.

This report evaluates opportunities to better integrate green infrastructure for postconstruction stormwater management into transportation projects, focusing specifically on roads and highways. The report summarizes transportation planning and structure, capital improvement planning, and the role of stormwater management in these processes. It examines the role of the Clean Water Act and other regulatory drivers for stormwater management on roads and highways and highlights case studies from across the country to identify best practices in integrating green infrastructure at the transportation planning and project development stages. The report also provides recommendations to fund green infrastructure on roads and highways. Although the overall focus is primarily on the federal context, the report provides two case studies in Toledo, Ohio and Atlanta, Georgia and develops specific recommendations for both the state Departments of Transportation (DOTs) and the cities themselves to better integrate green infrastructure into transportation projects. Both cities are moving forward with green infrastructure planning and these recommendations can provide additional resources as they address specific opportunities and challenges related to transportation.

Clean water and healthy communities go hand in hand. Urban areas are increasingly using green infrastructure to create multiple benefits for their communities. However, there have been questions whether strong stormwater standards could unintentionally deter urban redevelopment and shift development to environmentally damaging sprawl. Working with Smart Growth America, the Center for Neighborhood Technology, River Network and NRDC, we commissioned a report by ECONorthwest titled ”Managing Stormwater in Redevelopment and Greenfield Development Projects Using Green Infrastructure.” Highlighting several communities that are protecting clean water and fostering redevelopment, the findings show that clean water and urban redevelopment are compatible.

Storm events are increasing in frequency and severity throughout the Great Lakes basin, and the increase in rainfall is overwhelming our infrastructure. When rain falls in open, undeveloped areas not occupied by buildings or pavement, the water is absorbed into the ground and filtered by soil and plants. But, when water falls on roofs, streets, and parking lots, the water cannot soak into the ground. Instead, it enters the sewer system and it then has to be managed by municipalities and counties. STORMWATER goes from being the property-owner’s problem to the community’s problem really fast. And once it is the community’s problem, government agencies need to solve it.

Whether they go gray or green, for many communities, stormwater infrastructure repairs are no longer a luxury; they are a necessity to reduce chronic flooding and improve impaired rivers and streams. Communities need to repair old systems and build new, modern systems that embrace technological advances from the last 100 years. But, communities also need money to do it. A stormwater utility is an equitable way for communities to raise some of the money they need to fix the most immediate stormwater problems.

This Stormwater Utility Toolkit contains materials to ensure local leaders, city and county staff, and partners have the tools necessary to create a stormwater utility that is supported by the entire community. These tools are designed to give you the language and structure needed for jumpstarting a public engagement process. These tools are designed to be edited and personalized to fit your own community’s policies, values and personalities.

This toolkit contains:

- A stormwater utility overview and technical resources

- A strategy for building public support for a stormwater utility

- Sample outreach materials

- Draft press release

- Social media posts

- Website language

- Tips for running successful public meetings

- Sample stormwater utility ordinance language

You can also download:

- Stormwater Utility Kit factsheet

- Stormwater Utility Toolkit factsheet (en Español)

- Doorhanger

- Doorhanger (en Español)

- Microsoft Word document of templates (draft press release, social media posts, ordinance language, etc.)

Did you ever have a favorite place growing up that now, every time you drive by, it reminds you of your childhood? Whether it is a bridge, farm, a dam, or some other memorable landmark, there are historic structures and places across the country that have special significance to their communities.

Historic preservation laws were devised to protect cultural, archaeological, and architectural sites, structures, and landscapes that are significant to our heritage. While one generally envisions houses, cemeteries, and battlefields as having historic significance, other structures such as dams and bridges can be historically significant and may receive protection if their engineering is unique and/or they served an important role in local, state, or national history. Historic preservation and conservation organizations often partner on issues such as urban sprawl and smart growth, finding ways to simultaneously preserve our nation’s heritage and natural environment. As our nation’s infrastructure continues to age and we come to recognize its impact on the environment, river restoration projects can create opportunities for historic preservation and environmental restoration interests to work together.

In some cases, efforts to restore rivers involve proposals for removal of dams. A majority of dams were constructed prior to passage of both the National Historic Preservation Act (1966) and the National Environmental Policy Act (1969) and thus were built without the procedural safeguards now mandated by those statutes. Some of the dams that were once integral to our nation’s growth—providing power for grist mills and industrial cities, municipal drinking water, and electricity —no longer serve their intended purpose; costly repair may be needed to prevent their failure and ensure safety as these structures age. According to the American Society of Civil Engineers, one-quarter of the nation’s dams are older than 50 years; that number will increase to 85 percent by the year 2020. Because of their deterioration and additional documentation on the detrimental effects dams have on river ecosystems, dam removal has become an increasingly pragmatic method for restoring natural river functions and eliminating unsafe infrastructure. Removing a dam can provide many benefits, such as allowing migratory fish species access to historic spawning grounds, improving water quality and the natural movement of sediment and other nutrients, and reestablishing the natural flow regime . However, restoring environmental balance to our nation’s rivers may affect historic structures and archaeological sites, triggering state and federal historic preservation laws, and interest in preserving a piece of local history, as well as providing an opportunity for historic discovery .

Dam Removal and Historic Preservation: Reconciling Dual Objectives was written because too often advocates for river restoration through dam removal find themselves in the middle of a project and at odds with potential partners over matters of historic preservation. Dam removal proponents need to better understand the processes established to protect historic values so they can work more effectively in partnership with historic preservation interests to establish and achieve mutual goals. While the historic fisheries that helped build this nation, from providing sustenance to Washington’s troops during the American Revolution to their role as a sacred species to many tribes, deserve recognition, it is also important to respect the role of the dam, and in some cases the impoundment, in building local communities and sometimes as the social center for a town. The primary audiences for this report are dam removal project managers such as state agencies, community leaders, watershed groups, consultants. It is also our hope that local historic preservation societies and associations will also find it useful. Furthermore, we hope that this document will help parties involved in such endeavors to build constructive relationships and successfully reconcile potentially competing objectives.

This report begins with a primer on Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act, the federal law that applies to many proposed dam removal projects. State and local historic preservation laws may also pertain to proposed dam removal projects. In most cases, state and local historic preservation laws parallel the federal law, and compliance with all levels of jurisdiction can be achieved in a single process.

The report also examines opportunities for historic preservation and environmental interests to participate in productive discussions about whether a proposed dam removal could adversely affect historic resources and, if so, work together to identify methods for avoiding, minimizing or mitigating the adverse effects of the dam removal project.

Finally, this report provides case studies of actual dam removal projects that have addressed historic issues (see Appendix A), and an overview of federal, state, and tribal historic preservation laws (see Appendix B). Whether you are a dam owner, community member, state or federal agency, historical society, an advocate for river restoration and/or historic preservation, this report provides you with important information about reconciling the dual objectives of dam removal and historic preservation and making the often difficult choices between compelling cases to restore rivers or retain historic value.

Dam owners and communities are increasingly considering the option of removing dams that are unsafe, obsolete or simply causing more harm than good. But as more dam removal projects are proposed, many states are finding that the application of existing permitting processes can be unreasonably complicated, time consuming, and expensive for both the applicant and regulatory authorities. Indeed, dam failures have occurred during the prolonged process of permitting their controlled removal.

Despite the removal of at least 200 dams in the past six years, many states consider dam removal to be a new concept. And, due to its multidisciplinary nature, permitting decisions often fall under the jurisdiction of several entities. This can result in a number of factors that further complicate the permitting process: how to address conflicting goals, procedures and requirements among relevant authorities; the application of technical or regulatory standards that may be inappropriate for dam removal and associated restoration activities; and, the perennial challenge of effective inter- and intra-agency coordination.

Several states are now seeking advice from counterparts that have proactively addressed the regulatory challenges associated with dam removal projects. Many such challenges and recommendations were acknowledged in “Dam Removal: A New Option for a New Century.” This report was collaboratively developed by twenty-six experts from across the nation who participated in a two-year long dialogue on dam removal that was convened by The Aspen Institute.

Floodplains are an integral part of healthy rivers and floods are a natural occurrence on rivers. Natural floodplains provide many benefits to people and nature. They provide clean water supplies, recreation opportunities, habitat for fish and wildlife, and when left undeveloped they safely convey flood water.

Unfortunately, across the United States floodplains have been disconnected from rivers and modified on a massive scale resulting in a loss of floodplain benefits. But floodplains and their benefits to people and nature can be restored by getting water on the floodplain at the right time, in the right amount, and for the right duration to support natural floodplain habitats.

This report synthesizes the existing science on riverine floodplains to provide a single report that clearly defines what riverine floodplains are, why they’re important to healthy rivers, and how they can be restored. This report is intended to aid restoration practitioners, floodplain managers, river conservationists and others interested in laying a foundation for successful floodplain restoration efforts in their community and across the nation.

Riverine floodplains are dynamic systems that play an important role in the function and ecology of rivers. Where floodplains are connected to a river and periodically inundated, interactions of land, water, and biology support natural functions that benefit river ecosystems and people. In this paper we explore the hydrologic and ecological functions that floodplains provide, and how those functions are lost through floodplain disconnection and modification. We synthesize current river-floodplain science to develop an understanding of the biophysical and river flow attributes that underpin floodplain functions. We characterize four attributes that create and sustain functional floodplains; connectivity, variable flow, spatial scale, and habitat and structural diversity. To best restore floodplain systems, restoration practitioners should look beyond habitat features and focus on restoring floodplain functions. We propose a framework from which to consider process-based floodplain restoration using the four attributes of functional floodplains. Well-targeted restoration can return natural floodplain functions to rejuvenate rivers and benefit people.