Clean water and healthy communities go hand in hand. Urban areas are increasingly using green infrastructure to create multiple benefits for their communities. However, there have been questions whether strong stormwater standards could unintentionally deter urban redevelopment and shift development to environmentally damaging sprawl. Working with Smart Growth America, the Center for Neighborhood Technology, River Network and NRDC, we commissioned a report by ECONorthwest titled ”Managing Stormwater in Redevelopment and Greenfield Development Projects Using Green Infrastructure.” Highlighting several communities that are protecting clean water and fostering redevelopment, the findings show that clean water and urban redevelopment are compatible.

Storm events are increasing in frequency and severity throughout the Great Lakes basin, and the increase in rainfall is overwhelming our infrastructure. When rain falls in open, undeveloped areas not occupied by buildings or pavement, the water is absorbed into the ground and filtered by soil and plants. But, when water falls on roofs, streets, and parking lots, the water cannot soak into the ground. Instead, it enters the sewer system and it then has to be managed by municipalities and counties. STORMWATER goes from being the property-owner’s problem to the community’s problem really fast. And once it is the community’s problem, government agencies need to solve it.

Whether they go gray or green, for many communities, stormwater infrastructure repairs are no longer a luxury; they are a necessity to reduce chronic flooding and improve impaired rivers and streams. Communities need to repair old systems and build new, modern systems that embrace technological advances from the last 100 years. But, communities also need money to do it. A stormwater utility is an equitable way for communities to raise some of the money they need to fix the most immediate stormwater problems.

This Stormwater Utility Toolkit contains materials to ensure local leaders, city and county staff, and partners have the tools necessary to create a stormwater utility that is supported by the entire community. These tools are designed to give you the language and structure needed for jumpstarting a public engagement process. These tools are designed to be edited and personalized to fit your own community’s policies, values and personalities.

This toolkit contains:

- A stormwater utility overview and technical resources

- A strategy for building public support for a stormwater utility

- Sample outreach materials

- Draft press release

- Social media posts

- Website language

- Tips for running successful public meetings

- Sample stormwater utility ordinance language

You can also download:

- Stormwater Utility Kit factsheet

- Stormwater Utility Toolkit factsheet (en Español)

- Doorhanger

- Doorhanger (en Español)

- Microsoft Word document of templates (draft press release, social media posts, ordinance language, etc.)

Did you ever have a favorite place growing up that now, every time you drive by, it reminds you of your childhood? Whether it is a bridge, farm, a dam, or some other memorable landmark, there are historic structures and places across the country that have special significance to their communities.

Historic preservation laws were devised to protect cultural, archaeological, and architectural sites, structures, and landscapes that are significant to our heritage. While one generally envisions houses, cemeteries, and battlefields as having historic significance, other structures such as dams and bridges can be historically significant and may receive protection if their engineering is unique and/or they served an important role in local, state, or national history. Historic preservation and conservation organizations often partner on issues such as urban sprawl and smart growth, finding ways to simultaneously preserve our nation’s heritage and natural environment. As our nation’s infrastructure continues to age and we come to recognize its impact on the environment, river restoration projects can create opportunities for historic preservation and environmental restoration interests to work together.

In some cases, efforts to restore rivers involve proposals for removal of dams. A majority of dams were constructed prior to passage of both the National Historic Preservation Act (1966) and the National Environmental Policy Act (1969) and thus were built without the procedural safeguards now mandated by those statutes. Some of the dams that were once integral to our nation’s growth—providing power for grist mills and industrial cities, municipal drinking water, and electricity —no longer serve their intended purpose; costly repair may be needed to prevent their failure and ensure safety as these structures age. According to the American Society of Civil Engineers, one-quarter of the nation’s dams are older than 50 years; that number will increase to 85 percent by the year 2020. Because of their deterioration and additional documentation on the detrimental effects dams have on river ecosystems, dam removal has become an increasingly pragmatic method for restoring natural river functions and eliminating unsafe infrastructure. Removing a dam can provide many benefits, such as allowing migratory fish species access to historic spawning grounds, improving water quality and the natural movement of sediment and other nutrients, and reestablishing the natural flow regime . However, restoring environmental balance to our nation’s rivers may affect historic structures and archaeological sites, triggering state and federal historic preservation laws, and interest in preserving a piece of local history, as well as providing an opportunity for historic discovery .

Dam Removal and Historic Preservation: Reconciling Dual Objectives was written because too often advocates for river restoration through dam removal find themselves in the middle of a project and at odds with potential partners over matters of historic preservation. Dam removal proponents need to better understand the processes established to protect historic values so they can work more effectively in partnership with historic preservation interests to establish and achieve mutual goals. While the historic fisheries that helped build this nation, from providing sustenance to Washington’s troops during the American Revolution to their role as a sacred species to many tribes, deserve recognition, it is also important to respect the role of the dam, and in some cases the impoundment, in building local communities and sometimes as the social center for a town. The primary audiences for this report are dam removal project managers such as state agencies, community leaders, watershed groups, consultants. It is also our hope that local historic preservation societies and associations will also find it useful. Furthermore, we hope that this document will help parties involved in such endeavors to build constructive relationships and successfully reconcile potentially competing objectives.

This report begins with a primer on Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act, the federal law that applies to many proposed dam removal projects. State and local historic preservation laws may also pertain to proposed dam removal projects. In most cases, state and local historic preservation laws parallel the federal law, and compliance with all levels of jurisdiction can be achieved in a single process.

The report also examines opportunities for historic preservation and environmental interests to participate in productive discussions about whether a proposed dam removal could adversely affect historic resources and, if so, work together to identify methods for avoiding, minimizing or mitigating the adverse effects of the dam removal project.

Finally, this report provides case studies of actual dam removal projects that have addressed historic issues (see Appendix A), and an overview of federal, state, and tribal historic preservation laws (see Appendix B). Whether you are a dam owner, community member, state or federal agency, historical society, an advocate for river restoration and/or historic preservation, this report provides you with important information about reconciling the dual objectives of dam removal and historic preservation and making the often difficult choices between compelling cases to restore rivers or retain historic value.

October 2017

Whereas American Rivers’ mission is to protect wild rivers, restore damaged rivers, and conserve clean water for people and nature; and

Whereas the nation’s federal public lands, including national monuments, are home to many of the great rivers of the United States, such as the Columbia, Yellowstone, Colorado, Rio Grande, Missouri, and countless smaller rivers and streams that provide clean water for drinking, irrigation, fish and wildlife, and recreational opportunities for millions of Americans; and

Whereas by proclaiming national monuments pursuant to authority under the Antiquities Act, Presidents since Theodore Roosevelt have provided among the highest levels of protection for federal land and water resources; and

Whereas the Wild and Scenic River System created under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of 1968 is the most effective federal program for protecting wild, free-flowing rivers, particularly those on federal public lands; and

Whereas several designated and eligible Wild and Scenic Rivers could be negatively impacted by the Trump administration’s proposed revisions to prior national monument proclamations, including those establishing Bears Ears, Grand Staircase- Escalante, Rio Grande del Norte, Cascade-Siskiyou, and Katahdin Woods and Waters national monuments;

Now therefore be it resolved that the Board of Directors of American Rivers opposes any and all attempts by the Trump administration to reverse or revise prior national monument proclamations as such actions are potentially detrimental to the protection of federal public lands and waters.

Clean water is essential to our health, our communities, and our lives. Yet our water infrastructure – drinking water, wastewater and stormwater systems, dams and levees – is seriously outdated. In addition, we have degraded much of our essential natural infrastructure – forests, streams, wetlands, and floodplains. Global warming will worsen the situation, as rising temperatures, increased water demands, extended droughts, and intense storms strain our water supplies, flood our communities and pollute our waterways.

The same approaches we have used for centuries will not solve today’s water challenges. We need to fundamentally transform the way we manage water.

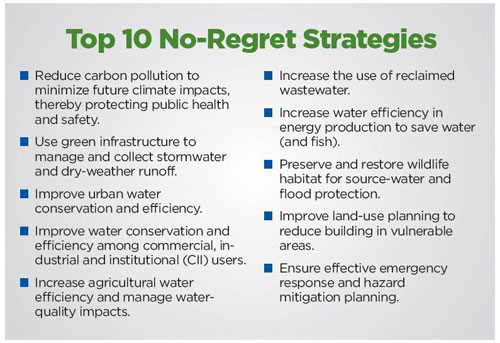

A 21st century approach would recognize “green infrastructure” as the core of our water management system. Green infrastructure is the most cost-effective and flexible way for communities to deal with the impacts of global warming. It has three critical components:

- Protect healthy landscapes like forests and small streams that naturally sustain clean water supplies.

- Restore degraded landscapes like floodplains and wetlands so they can better store flood water and recharge streams and aquifers.

- Replicate natural water systems in urban settings, to capture rainwater for outdoor watering and other uses and prevent stormwater and sewage pollution.

This report highlights eight forward-looking communities that have become more resilient to the impacts of climate change by embracing green infrastructure. They have taken steps to prepare themselves in four areas where the effects of rising temperatures will be felt most: public health, extreme weather, water supply, and quality of life. In each case study we demonstrate how these water management strategies build resilience to the projected impacts of climate change in that area and how the communities that have adopted them will continue to thrive in an uncertain future.

A Water Preparedness Guide for State Action

In recent years, a record number of extreme weather events including floods, heat waves, droughts, fires and snowstorms have wreaked havoc in the United States. As carbon pollution continues to warm the planet and fuel extreme weather, it is critical that states begin planning for a new “normal.”

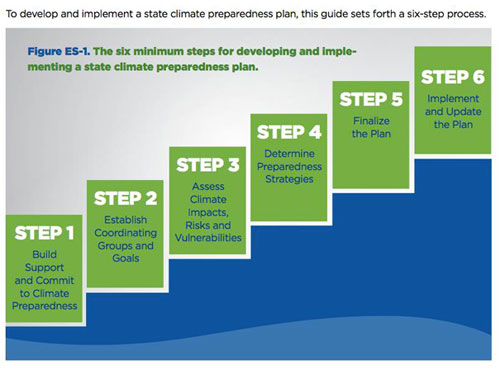

This guide provides information for state governments, water managers, and other stakeholders to use in preparing for the consequences of hotter temperatures, more variable and volatile precipitation events, and rising seas. By undertaking climate preparedness planning, states can better manage the impacts of climate change and protect the well-being of residents, communities, the economy and natural resources.

Fourteen different extreme weather events, including widespread drought and massive flooding, each caused damage of more than $1 billion in 2011. In 2012, scorching heat brought drought conditions to more than 65 percent of the country and contributed to large wildfire outbreaks in the West that burned more than 9.2 million acres. Severe storms and tornadoes also ravaged large swaths of the country. Additionally, in late October 2012, Superstorm Sandy devastated communities along the northeastern seaboard with record-breaking storm surges and historic flooding. In total, 11 extreme weather events in 2012 had costs exceeding $1 billion each. Moreover, 2012 was the hottest year since record-keeping began in the U.S. in 1895, As climate change increasingly fuels extreme weather, this trend of more extreme and record-breaking climate events shows no signs of abating.

Many extreme weather events as well as warmer temperatures, changing precipitation patterns and rising sea levels are expected to intensify as climate change continues. These deviations from historical climatic norms are affecting our communities and natural resources by threatening public health, affecting water availability and quality and energy production, placing vulnerable homes and infrastructure at risk, and jeopardizing vital ecosystems and habitats.

To address these challenges, more than 35 states have conducted planning to reduce the carbon pollution that contributes to climate change. Despite these efforts, however, states already are experiencing the impacts of climate change and will need to plan and prepare for the wide-ranging consequences of increasingly warmer temperatures, variable precipitation patterns and higher seas. To date, only 10 states have developed comprehensive plans to prepare for these climate-related impacts. Remarkably, most other states are not planning and remain ill-prepared for the challenges of climate change both now and in the years ahead.

States can use the six-step process in this guide to comprehensively plan and prepare for the water-related impacts of climate change. Although this guide focuses exclusively on climate impacts related to water, non-water impacts also will have wide-ranging ramifications for people, communities and ecosystems and must also be considered in climate preparedness planning.

Climate impacts will vary by region, and the strategies and resources available to manage these impacts will be shaped and limited by existing state laws, policies and resources. Accordingly, the process for developing a state climate preparedness plan contained in this guide is divided into three different tracks: Basic, Moderate and Robust. States can follow a single track throughout the planning process or choose to follow different tracks for each step. Additionally, specific examples are included to illustrate how some states have conducted their planning process. The most important message is that all states must start the planning process now. The signs of a changing climate are already being seen, and continued delay and inaction will only magnify the impacts and the cost of addressing them.

Ellerbe Creek Green Infrastructure Partnership: A NEW APPROACH TO RESTORING DURHAM’S STREAMS AND RIVERS

Our urban landscapes were not designed historically with the idea of protecting and restoring our natural environment. Weaving green stormwater infrastructure into an existing landscape can have significant benefits for both the human and natural communities by reducing flooding, improving water quality, reducing heat island affect, creating better access to green spaces, and many more! This report looks at the possibilities for using green stormwater infrastructure in a highly urbanized part of Durham, NC in the Ellerbe Creek watershed.

The most densely developed areas of the City and County were built along and on top of the headwaters of Ellerbe creek. The creek receives almost half of all the stormwater runoff from the city creating a huge problem for Ellerbe creek. The Durham State of Our Streams Report lists numerous pollutants in the creek that are directly related to excess stormwater runoff. Ellerbe Creek has been on the list of North Carolina’s most polluted water bodies since 1998 and stormwater pollution makes the creek nearly uninhabitable for aquatic life and at times dangerous for people.

Ellerbe Creek is the dirtiest stream in the Falls Lake Reservoir Watershed. High levels of nitrogen and phosphorous contribute to the current pollution problem in Falls Lake causing algae blooms and elevated bacteria levels leading to human health hazards, fish kills, drinking water contamination, and closed recreational beaches in the reservoir. Clean-up goals for the reservoir are in place and call for a 40% reduction in nitrogen and a 77% reduction in phosphorus. To restore clean water to the creek, the City of Durham will need to spend hundreds of millions of dollars using traditional stormwater management practices. This report shows a new innovative and cost effective approach to address these problems relying on integrating green infrastructure (e.g. rain gardens, green roofs, permeable pavement) into the city’s urban landscape to absorb and filter polluted stormwater and slowly release the cleaned, cooled water into the creek to restore its health and make it a more valuable resource for the community.

Removal of the Lower Snake River dams could have a significant benefit or a minimal negative impact on carbon emissions from grain transportation

The Grain Transportation Study released on July 8, 2022 by Dr. Miguel Jaller shows that carbon emissions see only a minimal decrease or increase if the lower Snake River dams are removed. While these findings may seem surprising, they are consistent with the one other study that focused directly on this question (Casavant and Bell, 2001).

Using one set of emissions factors, the new model showed a decrease in CO2 emissions of 9.14%. Using another, the model showed a slight increase of 1.37%.

- The Jaller study includes an estimate of current truck miles

- The Jaller study used the most recent publicly available emissions factors from studies that included truck, rail, and barge emissions, while a previous study appears to have used data that are over 40 years old.

- Rail is increasingly efficient

- This conclusion is well-supported by credible, independent studies

This study, commissioned by the Water Foundation and American Rivers, estimates the carbon emissions and other air pollution generated when transporting grain across the Pacific Northwest under two scenarios: current emissions and the emissions generated should the four Lower Snake River dams be breached. This study by Dr. Miguel Jaller adds to the body of research on the lower Snake River dams and is a data point that shows dam removal should have relatively little impact on carbon emissions as grain transportation shifts away from barges.

AN ASSESSMENT OF DEMAND FOR FLOODPLAIN EASEMENTS IN THE UPPER MISSISSIPPI RIVER BASIN

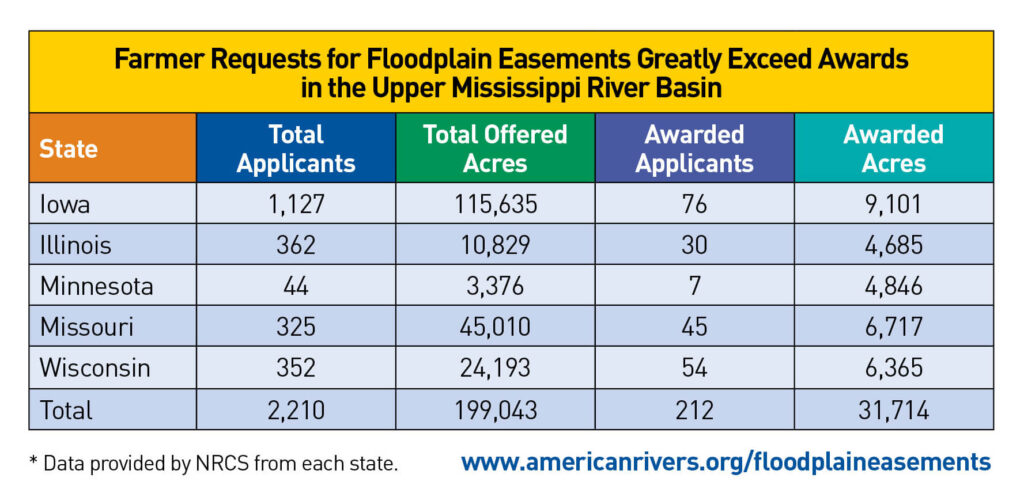

Floodplain easements are a land-management strategy that compensates landowners for permanently conserving flood-prone land. Floodplain easements provide multiple benefits, including storage of floodwater on the land, wildlife habitat, improved water quality and more.

USDA floodplain easements and flood damage-reduction investments are made through the Emergency Watershed Protection (EWP) Program, the EWP Program – Floodplain Easement Program (EWPP-FPE) and the Watershed Protection and Flood Prevention Program (WFPO) of the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS).

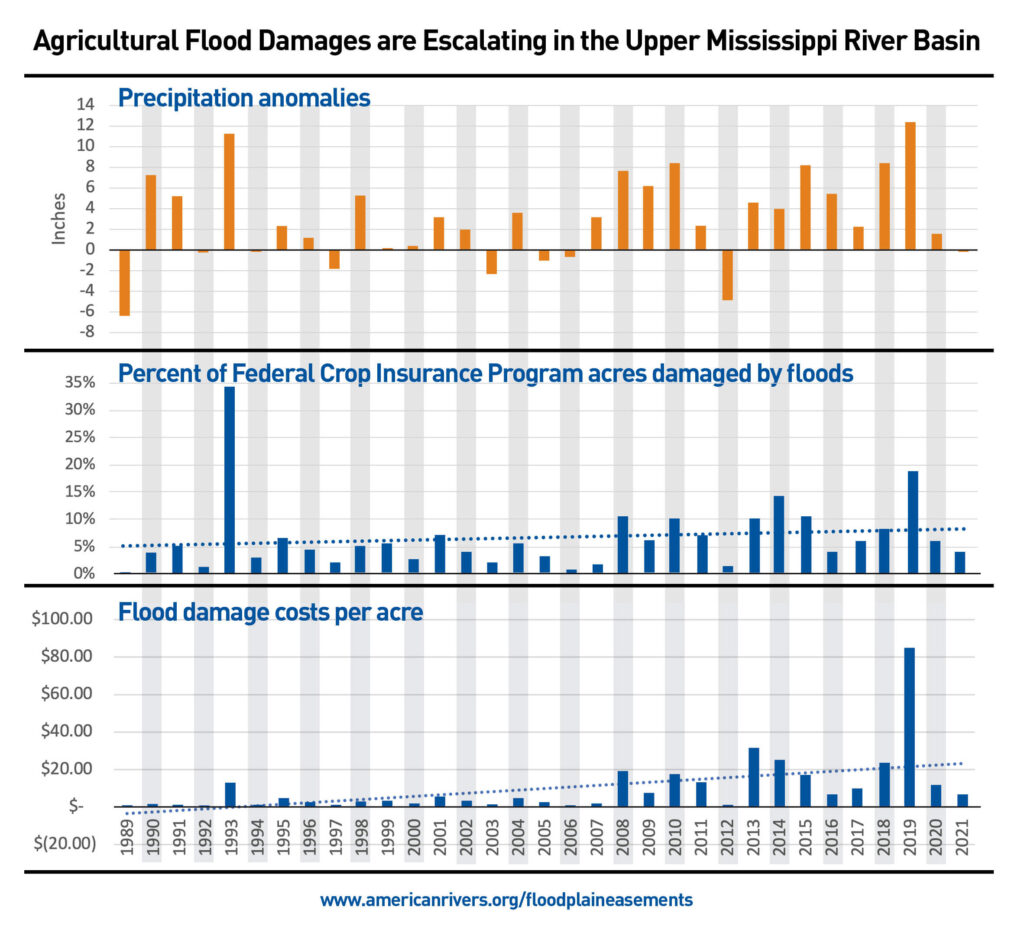

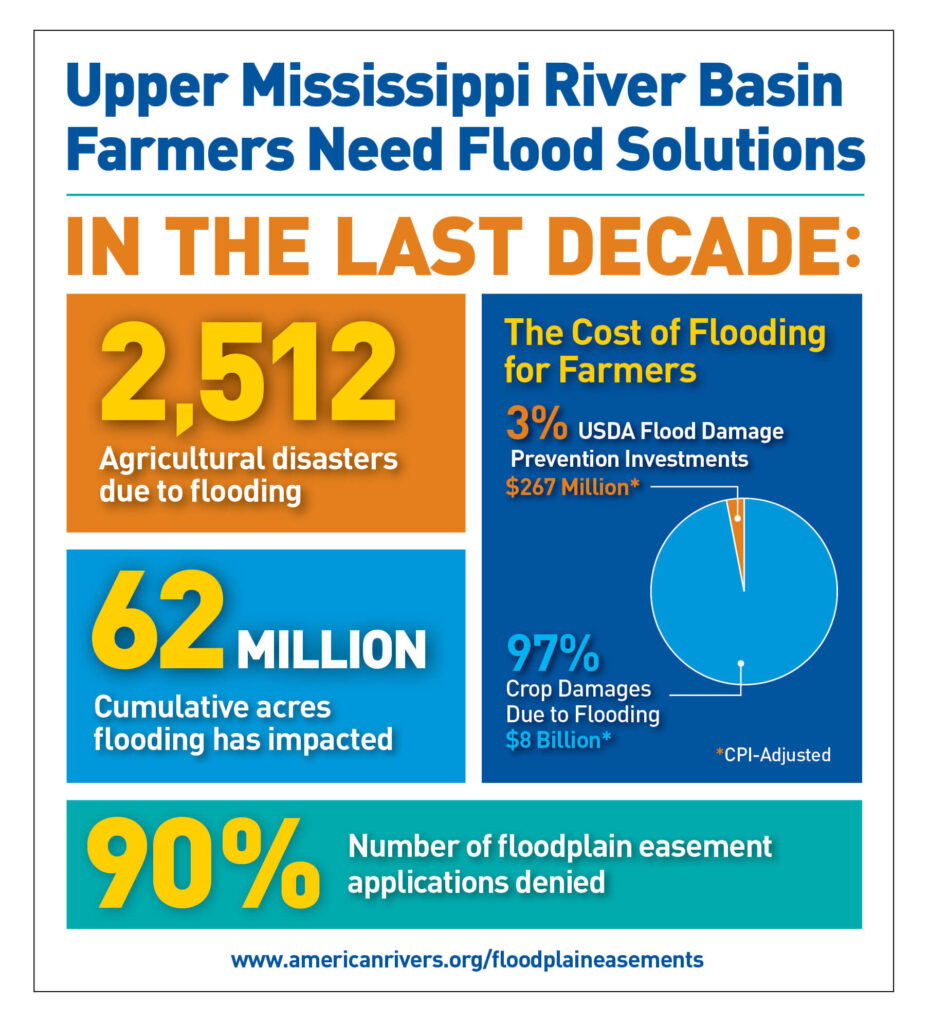

In the Upper Mississippi River Basin (UMRB), demand for flood assistant is very high, but these programs do not receive consistent, annual funding. Many years, Congress makes no funds available in the UMRB for flood damage reduction projects of any kind, despite the recurring costs of damages from flood and excess rain/moisture. The cost of damages from flood and excess rain/moisture ranks second only to drought in the UMRB, and these damages are escalating due to climate change.

Across the nation, flooding has caused $59.2 billion (CPI-adjusted) in damages over the last decade. Over that same period, farmers enrolled in the Federal Crop Insurance Program (FCIP) reported $29 billion in damages (CPI-adjusted) caused by floods and excess moisture, with the UMRB states representing 34 percent of those damages. The cost of flooding impacts on the nation and in the UMRB is rising as precipitation increases, and damages are expected to continue to escalate as climate-change impacts intensify.

Despite the significant and escalating amount of flood damage to crops on a regular basis, the EWPP and WFPO are only sporadically funded in the UMRB. Between 2011 and 2020, the USDA only invested $267 million (CPI-adjusted) into these two flood damage-reduction programs in the UMRB, while agricultural flood and excess rain/moisture damages exceeded $8 billion (CPI-adjusted).

In addition to saving farmers and taxpayers money, enrolling more acres in floodplain easements, and investing more in USDA flood risk reduction programs to plan floodplain easement and restoration would

- Promote resilient local economies by investing in floodplain projects that are rich in ecosystem services,

- Increase options for farmers to enroll acres that are routinely damaged by floods into a conservation program,

- Increase flood water storage in areas that are seeing significant rises in flood damages,

- Reduce nitrogen and phosphorus pollution in the Mississippi River by using floodplain restoration as a downstream water filtration tool,

- Prevent and slow the extinction of freshwater and floodplain-dependent species that are more at risk than marine and terrestrial species,

- Expand the use permanent easements that reduce long-term federal obligations, and

- Meet farmer demands for a more functional floodplain easement program.

The USDA Floodplain Easement Program needs to be reformed to enroll easement acres annually and make more substantial investments in flood damage reduction. To do this, Congress needs to include the following reforms in the 2023 Farm Bill

- Fund flood damage reduction and floodplain easement programs annually through USDA – Natural Resources Conservation Service.

- Establish a tracking and reporting system for floodplain easements within the Conservation Effects Assessment Project.

- Order USDA to collaborate with economic experts to better understand and quantify the ecosystem services provided by functional floodplains.

- Ensure floodplain easements are not subject to land-tenure requirements.

- Order USDA to collaborate with the US Army Corps of Engineers and the Federal Emergency Management Agency to prioritize investments in areas subject to recurring flood damages.

- Order USDA to develop Best Management Practices to reduce flood damages in the agricultural sector.

- Order USDA to improve guidance on floodplain restoration to meet multiple natural resource challenges.

Low-tech process based restoration (LTPBR) is a subset of process-based restoration (PBR) that seeks to re-establish natural stream processes by reconnecting incised streams with their floodplains and adjacent wetlands so that more frequent inundation of the floodplain occurs. Over the last decade, interest in designing and implementing LTPBR projects has grown considerably, and projects have been implemented across the west. This report reviews both published and unpublished research, case studies and project information on the effects of restoring incised and degraded headwater streams in Colorado and other western states with LTPBR.

LTPBR projects involve the use of simple, temporary, hand-built wood and rock structures that mimic natural beaver structures, acting as speed bumps that capture sediments to aggrade the stream. LTPBR approaches are substantially less expensive than form-based stream restoration approaches that employ heavy equipment.

Research and monitoring on LTPBR pilot projects have found a number of environmental and ecosystem service benefits. Benefits of LTPBR projects include:

- Drought and flood resilience: Studies indicate that healthy natural stream systems and restored headwater floodplains and wetlands recharge local aquifers. Reconnected floodplains enable infiltration of runoff into soils and wetlands, providing natural storage during spring runoff that can be slowly released to streams during the summer months. Healthy connected floodplains also help delay downstream flood peaks.

- Wildfire resilience: A 2020 study of large western US wildfires found that riparian vegetation around beaver complexes had a three times greater rate of survival than around stream segments without beavers.

- Improved habitat: By enhancing wetlands, LTPBR and beaver dams enhance important terrestrial habitat, and have also been shown to enhance fisheries

- Reduced Sedimentation: A study in England monitored 13 beaver ponds built from beavers re-introduced to a controlled 4.5-acre site. They determined that over the four years of monitoring the beaver ponds trapped on average 7.8 tons of sediment, totaling 101.5 tons. The authors concluded beaver ponds may help mitigate the downstream impacts of erosion and nonpoint source pollution.

- Increased water quality: Beaver dams have been shown to retain sediment and nutrients, as well as heavy metals, reducing downstream pollution levels.

- Increased forage: A 2018 study of LTPBR projects in Colorado, Oregon and Nevada showed that the projects increased vegetation productivity and extended it longer into the year. The authors noted that increased soil moisture due to the projects enabled vegetation to keep growing well during periods of low precipitation.

Research conducted for the report found ample evidence for many benefits from LTPBR. However, additional research is needed to better understand the hydrologic effects of LTPBR projects and beavers, including their potential to increase late-season flows and increase evaporation and water use by wetland vegetation. Existing research on the hydrologic effects has found the following:

- Key factors influencing the degree of LTPBR and beaver impacts on late-season flows include the extent of floodplain inundation and the length of time the inundation is sustained, as well as the porosity of structures.

- In regard to the potential for LTPBR to cause higher late-season flows and lower flows when a LTPBR project is first installed, one review found that small LTPBR projects tend not to have observable effects on streamflow, while larger projects can attenuate runoff and increase baseflows.

- A 2020 Montana study found that three years after the installation of a LTPBR project, the riparian vegetation had increased by ~25%, which resulted in a 0.7gpm increase in ET per structure. This small amount of decreased flow (0.0015cfs) was well below an amount that could be detected by a stream gage

Despite the documented benefits and low cost of LTPBR projects, challenges are impeding scaling up these projects. The social barriers to LTPBR and beavers are the largest challenges to solve. These include the potential impacts to human infrastructure from beaver dams, such as road and irrigation infrastructure flooding. This has stimulated the development of numerous solutions for preventing beaver from blocking water conveyances and ensuring sufficient water passage through beaver dams to prevent flooding problems. Additionally, more research is needed to understand the hydrologic effects of LTPBR projects and beaver complexes, including potential benefits to late-season flows and potential water rights impacts that can be avoided or mitigated. Demonstration projects in different types of stream systems and elevations are needed to provide more scientific understanding of these effects. Consulting with local stakeholders prior to developing an LTPBR project, carefully choosing location and project design, and ensuring compliance with any permitting requirements, can help overcome these challenges and enhance the chances for project success.

This report was written for American Rivers by Jackie Corday with Corday Natural Resource Consulting.

Water flowing in our streams, rivers, and creeks is a precious resource: It comprises two-thirds of our drinking water and is critical to the health of our communities. Rivers also serve as critical habitats for fish and wildlife. Plus, rivers sustain our economies, connect our communities to nature, and buffer our cities and towns against the worst impacts of climate change. Tragically, many rivers nationwide are polluted, dammed, and degraded, and most of the nation’s water infrastructure is in a state of disrepair.

With recent investments from the bipartisan infrastructure law and the Inflation Reduction Act, now is the time to ensure these much-needed funds are directed to clean water and river restoration projects that improve the lives and climate resiliency of people in rural and urban areas — and particularly Communities of Color and Tribal Nations, who are disproportionately impacted by water pollution, droughts, floods, and environmental degradation.

We must ensure federal agencies have the tools, resources, technical assistance, and capacity they need to solve today’s complex water challenges. Federal investment in efforts including natural infrastructure and river restoration can make rivers healthier and water cleaner for everyone.

The Fiscal Year 2024 River Budget outlines recommended federal priorities for agencies, including the Department of Interior, Department of Agriculture, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and Environmental Protection Agency, to promote climate-smart agriculture practices, improve water infrastructure, restore watersheds, modernize flood management, and support dam removal and rehabilitation. The River Budget spotlights needs in five key categories:

Promote climate-smart agriculture: Innovative conservation practices on farms and working lands can regenerate ecosystems, improve irrigation, and bolster agriculture. Yet water shortages are becoming increasingly common due to less rainfall, resulting in historic droughts. In 2022, the Mississippi River dropped to record-low water levels. In the Southwest, farmers, ranchers, and landowners are experiencing the most extreme drought in more than a millennium. In the Fiscal Year 2024 appropriations process and upcoming Farm Bill, Congress and the Administration must prioritize climate-smart agriculture to support rural communities, and a critical sector of our economy.

Restore watersheds: From the Great Lakes to the Chesapeake Bay, watersheds are essential to keeping ecosystems healthy and functioning as nature intended. These lands naturally store water, filter pollution, sequester carbon, control erosion and sediment, and provide habitats for wildlife. These natural services help strengthen communities in the face of climate change, and can buffer us against severe floods, droughts, and fires. Healthy watersheds also provide recreation benefits, including fishing, boating, swimming, hiking, biking, and wildlife watching. In 2020, hunters and anglers contributed $149 billion to the national economy, supported 970,000 jobs, and created over $45 billion in wages and incomes.

Modernize flood management: Inland and coastal communities need relief as environmental pressures and natural disasters including hurricanes and floods, threaten people and property. Nearly 41 million people live in flood-prone areas. Our nation needs to continue investing in flood-management solutions that protect communities and safeguard rivers. We call on Congress and the Administration to implement nature-based solutions to managing watersheds, floodplains, wetlands, and other water sources. This includes better coordination-mapping technology to produce maps that inform communities about flood risk and help them better prepare for extreme weather.

Improve water infrastructure: Our nation’s water infrastructure is essential to providing safe, reliable, affordable clean water. It is vital to public health, and to ensuring clean, healthy rivers. Every dollar invested in water infrastructure generates $2.20 in economic activity. Yet decades of underfunded and deferred maintenance has pushed the nation’s water infrastructure to the brink of collapse. Many cities hold, treat, and deliver water using pumps and pipes that are more than 100 years old. Older water systems contain bacteria, lead, and other hazardous chemicals, which exposed thousands to untreated water in Flint, Michigan, and Jackson, Mississippi. We must avoid humanitarian disasters by securing significant water infrastructure investments that protect the health of people and rivers.

Remove and rehabilitate dams: Removing dams and improving dam safety can restore natural functions of rivers, help fish and wildlife species recover, create jobs, and increase our communities’ resilience to droughts and floods. Dams disrupt the natural ecosystem by impacting water quality, cutting off migration routes, isolating habitats, and destroying fish spawning grounds. Some dams pose serious public safety risks. Prioritizing funding to remove, rehabilitate, and/or retrofit dams is the best way to bring life back to damaged rivers and protect communities.

These federal spending priorities in the Fiscal Year 2024 River Budget are a critical defense against the impacts of climate change and water pollution. The annual federal spending process charges Congress to work with the administration and focus on investments that are key to restoring rivers, from remote mountain streams to urban waterways. Taken together, these investments will improve public health and safety, boost climate resilience, deliver economic benefits, and improve agency programs that are responsible and responsive to meeting community needs.

For questions, contact:

Jaime D. Sigaran, Associate Director, Policy and Government Relations

jsigaran@americanrivers.org

Ted Illston, Vice President, Policy and Government Relations

tillston@americanrivers.org

The Bay Delta Conservation Plan (BDCP) is more than 15,000 pages long and covers a wide range of issues ranging from water supply, new facility construction, aquatic and terrestrial ecosystem management, governance and costs. Few outside of the handful of people deeply involved in BDCP actually know what is in the document due to its imposing size. This is particularly true for the various stakeholder groups who lack either the staff or the technical capacity to review the document and to evaluate the complex analyses that underpin it.

Saracino & Mount, LLC, was asked to assemble a panel of independent experts to review portions of the Plan to help guide decision making by two non governmental organizations: The Nature Conservancy and American Rivers. Guided by a narrow set of questions about how the Plan would impact water supply and endangered fishes, the panel reviewed the Plan documents and conducted analyses of data provided by the project consultants. The following document is a summary of our results.