Historically, the infrastructure that makes up our water systems has been funded by government grants, loans, and by traditional municipal bond issuances. Adding private investment, in the form impact bonds, P3s or outcomes-based financing, can create additional opportunities to deliver water projects efficiently and effectively. This report explores innovative finance models through the lens of economically disadvantaged communities in Northern California.

Senator Tom Udall

Hart Senate Office Building, 531

Washington, DC 20510

Senator Martin Heinrich

Hart Senate Office Building, 303

Washington, DC 20510

Dear Senators Udall and Heinrich,

Thank you for introducing the M.H. Dutch Salmon Greater Gila Wild and Scenic River Act, which would protect nearly 450 miles of the Gila and San Francisco Rivers and their tributaries as Wild and Scenic. For nearly a decade, a groundswell of support for these protections has been growing from Tribes, sportsmen and women, veterans, small business owners, faith and civic organizations, local municipalities and governments, and outdoor recreation and conservation organizations. Today, we join them in applauding your leadership on this effort.

At a time when Americans are experiencing vast economic hardship and unprecedented uncertainty from the COVID-19 pandemic, designating these rivers and tributaries as Wild and Scenic will ensure local, rural economies that depend upon time-tested traditions like grazing, ranching, and hunting and fishing can continue. Additionally, it gives us all hope — and an indomitable reminder of the value of our wild places.

The Gila and San Francisco rivers, along with their tributaries, make up one of the largest free-flowing watersheds remaining in the Lower 48 states. Flowing through the nation’s first wilderness area, a place of which Aldo Leopold wrote, “Wilderness is the one kind of playground which mankind cannot build to order… I contrived to get the Gila headwaters withdrawn as a wilderness area, to be kept as pack country, free from additional roads, ‘forever.’”

These wild and rugged landscapes form the bedrock of our outdoor economy, providing boundless inspiration and giving roots to our American way of life. Simply put, safeguarding our common waters and lands is vital to our economy, health and communities.

Outdoor recreation is big business in New Mexico, generating nearly $10 billion in consumer spending, roughly $3 billion in wages and salaries, $623 million in state and local tax revenues, and directly employing 99,000 people. And it doesn’t stop there. Each year, the outdoor recreation industry generates $887 billion in consumer spending and 7.6 million jobs.

Never has it been more vital for us to come together as a country and work together to protect our communities and wild places for all of us today and for future generations. Thank you for continuing to do what it takes to fight for our shared values — even, and especially when it hasn’t been easy. We stand with you and call on the Senate to move this legislation, and for it to quickly become law.

Sincerely,

The OARS Family of Companies

Tyler and Clavey Wendt, Owners

Merlin, Oregon and Angels Camp, California

Aspen Skiing Company

Auden Schendler, VP Sustainability

Aspen, Colorado

REI Co-op

Taldi Harrison, Government and Community Affairs Manager

Kent, Washington

Taos Fly Shop

Nick Streit, Owner

Taos, New Mexico

The Reel Life

Ivan Valdez, Owner

Santa Fe, New Mexico

Red River Angler and Sport

Sloan Covington, Owner

Red River, New Mexico

Yakima Products Inc.

Ryan Martin, CEO

Beaverton, Oregon

Alpacka Raft

Thor and Sarah Tingey, Owners

Mancos, Colorado

Buckley Associates

Lucy Buckley, CEO

Boulder, Colorado

LaSportiva

Jonathan Lantz, President

Boulder, Colorado

Sawyer Paddles

Zac Kauffman, CEO

Gold Hill, Oregon

Ruffwear

Allison Miles, Community and Content Manager

Bend, Oregon

Backbone Media

Penn Newhard, Founder

Carbondale, Colorado

Wild Rye

Cassie Able, Founder

Ketchum, Idaho

Uinta Brewing Company

Jeremy Ragonese, President

Salt Lake City, Utah

KEEN

Erik Burbank, Chief Brand Officer

Portland, Oregon

Nite Ize

Cassie Ryan, Social Media Specialist

Boulder, Colorado

Far Flung Adventures

Steve Harris, CEO

El Prado, New Mexico

Kokapelli Raft Adventures

Kelly Gossett, Owner

Santa Fe, New Mexico

New Mexico River Outfitters Association

Steve Harris, Public Affairs Director

Embudo, New Mexico

Patagonia

Hans Cole, Director of Environmental Campaigns and Advocacy

Ventura, California

Protect Our Winters

Torrey Udall, Director of Development

Boulder, Colorado

Justin Balie Photography

Justin Balie, Owner

Nehalem, Oregon

rygr

Brian Holcombe, Principle

Carbondale, Colorado

Mountain, Stream, and Trail Adventures, LLC

Michael T Carney, Co-founder

Albuquerque, New Mexico

AIRE, Inc.

Alan Hamilton, Co-founder

Bosie, Idaho

Orvis

Simon Perkins, President

Sunderland, Vermont

Badfish SUP

Mike Harvey, Co-owner

Salida, Colorado

Hydro Flask

Larry Witt, President

Bend, Oregon

Klean Kanteen

Caroleigh Pierce, Nonprofit Outreach Manager

Chico, California

Los Rios River Runners

Francisco Guevara, Owner

Santa Fe, New Mexico

Santa Fe Rafting

Jarrod McClure, Owner

Santa Fe, New Mexico

New Mexico River Adventures

Wendy Gontram, Owner

Embudo, New Mexico

New Wave Rafting

Britt Huggins, Owner

Embudo, New Mexico

Under Solen Media

Emily Nuchols, Owner

Portland, Oregon

NRS

Mark Deming, Director of Marketing

Moscow, Idaho

The Conservation Alliance

Brady Robinson, Executive Director

Bend, Oregon

Jack’s Plastic Welding Inc.

Errol Baade, CEO

Aztec, New Mexico

NM Outdoor Recreation Business Alliance

James Glover, Co-Director

Farmington, New Mexico

In recent years, green infrastructure has become a proven solution to address many of the challenges created by urban stormwater. By soaking up stormwater and harvesting it to grow trees and plants, green infrastructure can provide multiple benefits to landowners, neighborhoods and communities. Green infrastructure can be particularly useful for transportation projects by reducing stormwater pollution at its source, minimizing localized street flooding, and cooling urban roadway systems.

American Rivers is committed to supporting Transportation Departments in their move to embrace green infrastructure solutions. Our previous report, Rivers and Roads, highlights techniques for planning, funding and designing green infrastructure for urban areas, and relates two case studies for using nature-based solutions to reduce roadway runoff impacts in Atlanta and Toledo.

However, this report and many of the resources that highlight green infrastructure techniques feature programs and projects from the Pacific Northwest or Atlantic Northeast – places where it rains a lot. Building green infrastructure for desert communities requires a slightly different skill set and expertise.

Working with long-time partners in Tucson, Arizona, American Rivers produced this resource library tailored for transportation professionals and community planners working in arid environments. While primarily focused on Tucson and the surrounding Pima County region, the planning, funding, and project design elements it discusses will be relevant to other Southwestern communities.

The report is broken down into three sections: Integrating Green Infrastructure into Project Planning, Funding Green Infrastructure as Part of Transportation Projects, and Green Infrastructure Design, Implementation, and Maintenance for Arid Landscape Transportation Projects. It contains stepwise checklists for integrating green infrastructure into roadway projects, as well as design and maintenance checklists. An annotated bibliography of design guides provides links to technical standards developed by Southwestern cities.

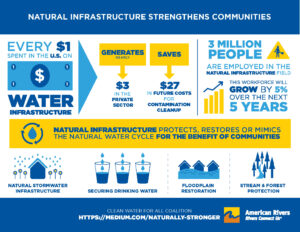

We are at a pivotal moment in time. In the wake of COVID-19, Congress has made — and is considering additional — investments to jump-start the economy and bring the millions of unemployed Americans back to work. At the same time, Congress has a historic opportunity to make significant investments in our crumbling infrastructure, which has been underinvested in for decades. Investment in water infrastructure and healthy rivers will not only create jobs, it will also strengthen our communities, improve public health and safety, address longstanding injustices and improve our environment.

Clean water and healthy rivers are smart investments that can contribute significantly to economic growth and job creation. The Value of Water Campaign3 estimated that every $1 million spent on water infrastructure in the United States generates more than 15 jobs throughout the economy. Similarly, the University of Oregon4

found that every $1 million invested in watershed restoration creates 16 new or sustained jobs on average. Healthy rivers also spur tourism and recreation, which many communities rely on for their livelihoods. The Outdoor Industry Association’s National Recreation Economy Report5 found that Americans participating in watersports and fishing spend over $174 billion on gear and trip related expenses. And, the outdoor watersports and fishing economy supports over 1.5 million jobs nationwide.

To put our economy back on track, while addressing some of our nation’s most pressing challenges, Congress must increase funding for healthy rivers and clean water. Any infrastructure, economic stimulus or jobs bill crafted to address the COVID-19 economic crisis must include major investments in water infrastructure, flood management and watershed restoration. American Rivers recommends Congress invest $500 billion for rivers and clean water over the next 10 years. We recommend an initial investment of at least $50 billion to address the urgent water infrastructure needs associated with COVID-19 and shovel-ready projects to improve flood management and restore rivers across the country.

As climate change continues to roll out new and increasingly unpredictable conditions all over the country, it’s becoming clear that, for some communities, water scarcity is a problem that isn’t going to be solved when the weather “goes back to normal.” This is especially true when extremes of flood and drought are compounded by landscape urbanization, water use and outdated infrastructure. How do we solve seemingly insoluble environmental problems like these through partnerships and collaborations forged at home, in our communities, watersheds and local governments?

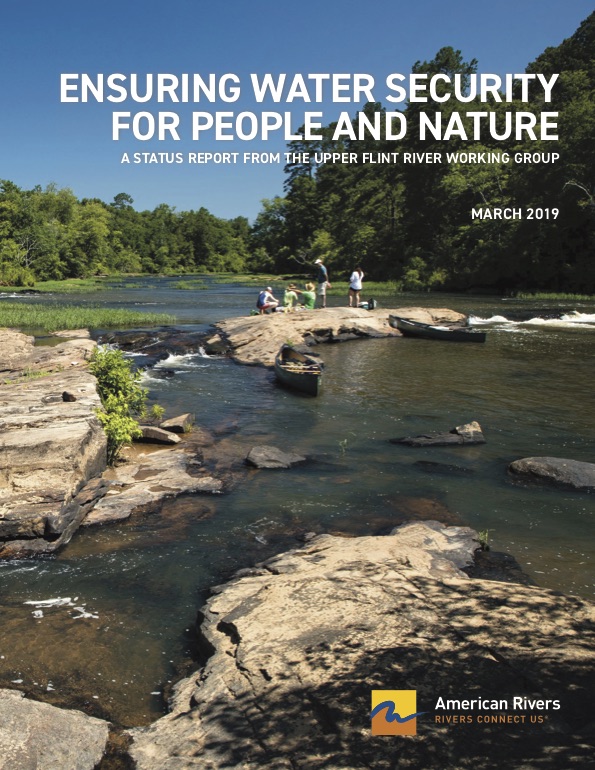

In Georgia, American Rivers and our partners are working on these challenges in the upper Flint River, whose headwaters spring up just north of Atlanta’s international airport—the busiest airport in the world—and flow to the Fall Line of central Georgia between Macon and Columbus. Since 2013, American Rivers has convened the Upper Flint River Working Group, a voluntary collaborative of diverse partners who share the same vision for this watershed: to maintain a river system healthy enough to support the various social, ecological, recreational and economic benefits the upper Flint River system provides. These include water supply, recreation, fisheries, property values and a healthy river ecosystem, to name a few. The Working Group is made up of the leadership of all the large water utilities in the upper basin, local conservationists, non-profit conservation organizations, and Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport staff.

Arguably more than any river in the Southeast—or even the eastern United States—the Upper Flint is suffering the strains of water scarcity. Since 2000, the river basin has experienced four major droughts that have caused alarmingly low river river flows: 30 to 50 percent lower than anything seen in the 20th century, even during the driest times. During these dry periods, the upper Flint shrinks to a trickle, signaling the river system is less resilient to drought conditions than it once was. This makes the upper Flint a good place to dig deeper into a collaborative approach to addressing the challenges of water scarcity.

After five years of working together, the Working Group developed Ensuring Water Security for People and Nature, a report outlining the group’s progress and the inroads it’s made into addressing water security and drought resilience in the basin, both for the ecology of the river and the communities that depend on the river for water supply.

The report, published in March 2019, has three purposes:

- To document the five-year history of the Upper Flint River Working Group, where dialogue and collaboration have led to key achievements and successes. These successes include new water infrastructure that returns more water to the Flint and protects major tributaries from extreme low flows, initial improvements to reservoir management on the county level, new research performed by municipal governments into regional water supply dynamics, and green stormwater infrastructure installed at the Atlanta airport.

- To publish the group’s consensus-based goals for managing the river system in the future.

- To share future plans for actions to improve water availability for people and nature in the basin, such as pursuing water efficiency and conservation, further improving reservoir management, utilizing green infrastructure at multiple scales to manage urban runoff, and protecting lands that support healthy flows in the Flint.

As Working Group participants have gained an increased awareness of the critical nature of drought flows in the upper Flint, they have chosen to emphasize and accelerate the implementation of projects that support mutual goals of the group. All these projects—and more on the way—will improve drought resilience and water availability for people and nature in the upper Flint basin in the future. Going forward, the Working Group also plans to collaborate with additional river stakeholders and with scientists researching the upper Flint who can help improve our collective understanding of environmental water needs and hydrologic trends in the basin.

In addition to restoring healthy flows and drought resilience to the Flint River, American Rivers and the Upper Flint Working Group are testing a process as much as a product. We’re hopeful that further success in this voluntary, collaborative process for addressing shared water resources can help inform the way communities nationwide approach 21st-century water scarcity and security challenges.

Around the country, municipalities, stormwater agencies and their partners are developing creative solutions to close the resource gap. Stormwater credit banks and trading programs provide compliance flexibility while bringing private capital and property into the solution mix. Optimized grant programs can target priority outcomes and align with other funding sources. Public-private partnerships and pay-for-performance contracting models can bring private sector financing to bear. “Green bonds” match environmental and community benefits to public expenditures.

These solutions also open the possibility of developing projects on private property. When private property owners can contribute to, and benefit from, municipal green stormwater infrastructure programs, limited public funding and resources can be leveraged to create multiple benefits for clean water and communities.

The principal law that regulates drinking water safety is the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA). The SDWA provides a comprehensive set of water quality standards, enforcement authority, and reporting requirements for water systems that provide water to the public. Like other environmental laws that follow the cooperative federalism model, the federal government provides states the opportunity to implement the law themselves. The SDWA provides minimum standards that states can either adopt or improve on. In other words, the SDWA acts as the federal floor; any state that wishes to implement it must do so at least as protectively as the federal government, but can have as high a ceiling as it wishes.

With increased attention on localized public health concerns related to drinking water, it is up to everyone to learn where their drinking water comes from; understand what consumer confident reports tell us; and advocate for improvements in laws, regulations, and policies that directly affect the safety of our drinking water. We also need to better understand where our influence and advocacy efforts are needed. Is our local issue a result of a shortcoming or failure of federal, state, or local government? Or could it be a result of all three? It may be hard to tell before knowing where specific decisions related to concerns are being made and how best to understand complex government provisions that may be spread out in numerous laws, supporting regulations, and guidance documents.

In order to provide a snapshot of information to the reader, we have focused this report on eight aspects of the SDWA: MCLs, treatment techniques, and monitoring standards; regulation of lead as a drinking water contaminant; consumer confidence reporting; loans and grants; public participation in standards development, permits, and enforcement; operator certification; management of drinking water emergencies; and management of algal blooms. While not regulated by the SDWA, as a way to better understand states’ overall approach to drinking water, the report also looks at how states regulate private water well protection through private well construction codes and through regulation of other activities that can pollute private wells. It also addresses PFAS, which are not currently regulated by an MCL.

For each topic, the report answers two fundamental questions. First, how does the federal law address the topic? Second, how does each state address the topic differently? The focus is on actual laws. For that reason, it addresses mostly statutes and regulations.

This report is introductory in nature, yet provides a wealth of information. In order to get the most out of the information provided and advance your advocacy efforts, utilize the end notes where you’ll find specific laws, documents, and links that will take you further into your journey to better understand the SDWA in general and how your Great Lakes state is implementing the SDWA.

October 2017

Whereas American Rivers’ mission is to protect wild rivers, restore damaged rivers, and conserve clean water for people and nature; and

Whereas the nation’s federal public lands, including national monuments, are home to many of the great rivers of the United States, such as the Columbia, Yellowstone, Colorado, Rio Grande, Missouri, and countless smaller rivers and streams that provide clean water for drinking, irrigation, fish and wildlife, and recreational opportunities for millions of Americans; and

Whereas by proclaiming national monuments pursuant to authority under the Antiquities Act, Presidents since Theodore Roosevelt have provided among the highest levels of protection for federal land and water resources; and

Whereas the Wild and Scenic River System created under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of 1968 is the most effective federal program for protecting wild, free-flowing rivers, particularly those on federal public lands; and

Whereas several designated and eligible Wild and Scenic Rivers could be negatively impacted by the Trump administration’s proposed revisions to prior national monument proclamations, including those establishing Bears Ears, Grand Staircase- Escalante, Rio Grande del Norte, Cascade-Siskiyou, and Katahdin Woods and Waters national monuments;

Now therefore be it resolved that the Board of Directors of American Rivers opposes any and all attempts by the Trump administration to reverse or revise prior national monument proclamations as such actions are potentially detrimental to the protection of federal public lands and waters.

Clean water is essential to our health, our communities, and our lives. Yet our water infrastructure – drinking water, wastewater and stormwater systems, dams and levees – is seriously outdated. In addition, we have degraded much of our essential natural infrastructure – forests, streams, wetlands, and floodplains. Global warming will worsen the situation, as rising temperatures, increased water demands, extended droughts, and intense storms strain our water supplies, flood our communities and pollute our waterways.

The same approaches we have used for centuries will not solve today’s water challenges. We need to fundamentally transform the way we manage water.

A 21st century approach would recognize “green infrastructure” as the core of our water management system. Green infrastructure is the most cost-effective and flexible way for communities to deal with the impacts of global warming. It has three critical components:

- Protect healthy landscapes like forests and small streams that naturally sustain clean water supplies.

- Restore degraded landscapes like floodplains and wetlands so they can better store flood water and recharge streams and aquifers.

- Replicate natural water systems in urban settings, to capture rainwater for outdoor watering and other uses and prevent stormwater and sewage pollution.

This report highlights eight forward-looking communities that have become more resilient to the impacts of climate change by embracing green infrastructure. They have taken steps to prepare themselves in four areas where the effects of rising temperatures will be felt most: public health, extreme weather, water supply, and quality of life. In each case study we demonstrate how these water management strategies build resilience to the projected impacts of climate change in that area and how the communities that have adopted them will continue to thrive in an uncertain future.

A twist on a familiar adage amongst water managers is “when it rains, it drains.” While not unique to Pennsylvania, in suburban and urban municipalities, centuries of strong growth, including recent decades of sprawl, have transformed much of the state’s natural land cover into extensive impervious surface. As a result, instead of soaking into soils and groundwater, stormwater drains directly into rivers and streams contributing to — and often exacerbating — flooding and pollution.

The ideal approach to resolving the adverse impacts of stormwater would be to return the landscape to its natural cover. A highly cost-effective, efficient, and viable solution is to adopt “green” infrastructure practices that protect, restore, and replicate nature’streatment of stormwater. Green infrastructure includes low-impact development practices at new and re-developing sites, and the incorporation of features such as rain barrels, green roofs, and permeable pavement on already-developed sites. Green infrastructure is becoming widely understood and accepted, and is being implemented on the ground in cities across the nation, including Pittsburgh and Philadelphia.

The challenge to broader implementation in smaller municipalities throughout the Commonwealth is ensuring that regulatory, management, and funding institutions work in concert to promote the use of green infrastructure. To begin with, Pennsylvania is challenged by historical patterns of funding water management that have prioritized wastewater treatment and drinking water delivery over stormwater management. Traditionally, funding also has favored hard structural solutions to management (known as “gray” infrastructure) rather than nonstructural or “green” practices that address the problems associated with runoff at its source. Further, regulation of stormwater management has failed to sufficiently integrate greener solutions and to promote nonstructural practices in the management of Pennsylvania’s water resources.

The unfortunate result is that Pennsylvania has received a failing grade for its management of stormwater. In 2009, the Chesapeake Stormwater Network ranked Pennsylvania last of five Chesapeake Bay states on its Baywide Stormwater scorecard. With an overall grade of “D” for implementing a stormwater program that meaningfully protects and restores the Bay, Pennsylvania received an “F” with regard to its funding of stormwater management needs to address the 21st century challenges posed by aging and deteriorating infrastructure, increasing demands on water use, and impacts of a changing climate.

Today, Pennsylvania has an unprecedented and timely opportunity to transform its water infrastructure. Following federal guidance, state regulations are being revised to incorporate greener approaches to stormwater management. Also, suggestions to adopt innovative management practices, including green infrastructure and conservation measures, are evolving from stakeholder discussions. Finally, funding institutions are quickly adapting to finance green infrastructure, catalyzed in part by the passage of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA) which includes investments in green infrastructure and water efficiency advocated for by American Rivers. In 2009, $44.6 million in federal stimulus funds directed toward Pennsylvania for water infrastructure has leveraged more than $66 million in spending the state describes as “green.”

It is imperative to seize this chance to make progressive and institutional “green” investments to avert “pouring money down the drain.” Pennsylvania’s rivers and communities depend upon clean water and require a swift remedy to current infrastructure woes. “Green” solutions have the added benefit of facilitating the resilience rooted in nature that communities need to adapt to the impacts of climate change on vital freshwater resources.

Towards those ends, American Rivers has investigated the capacity of Pennsylvania’s funding institutions to support efficient and cost-effective green infrastructure practices to enhance sustainable water management over the long term. Our findings highlight several recommendations for formalizing funding for green infrastructure that will help Pennsylvania municipalities achieve clean and abundant supplies of fresh water for healthy communities and future generations.

These recommendations will facilitate efficient and cost-effective green practices to address Pennsylvania’s stormwater management challenges. The results will yield benefits in the form of reduced tertiary treatment costs, decreased flood damages, and healthier ecosystems and communities throughout Pennsylvania that are also better prepared to adapt to a changing climate.

The majestic Colorado River cuts a 1,450-mile path through the American West before drying up well short of its natural finish line at the Gulf of California. Reservoirs once filled to the brim from the river and its tributaries are at historic lows due to an unprecedented drought and growing human demands. Diminished stream flows now pose serious challenges for wildlife and recreation, as well as cities, farms, and others who rely upon the river. Steps currently being taken to improve the situation are not up to the task of bringing the river system back into balance and providing a reliable water supply for all the communities who depend upon the Colorado River.

Fortunately, we have five feasible, affordable, common-sense solutions that can be implemented now to protect the flow of the river, ensure greater economic vitality, and secure water resources for millions of Americans.

- Municipal conservation, saving 1 million acre-feet

- Municipal reuse, saving 1.2 million acre-feet

- Agricultural efficiency and water banking, saving 1 million acrefeet

- Clean, water-efficient energy supplies, saving 160 thousand acrefeet

- Innovative water opportunities, generating up to 1 million acrefeet

Proven Solutions, Progress We Can See

Federal, state and local officials can help make most these changes today, and start reaping many benefits within a year or two. A few solutions will require longer-term collaboration among governments and users, sometimes a rarity in today’s national political and economic climates. Yet, Colorado River basin states and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation have a solid record of increased cooperation over the last two decades. What’s more, many basin states are already taking steps to update their state water plans with innovative, creative ideas for improving water management. The common-sense and money-saving approaches outlined here are the best path forward. We’ve already seen strong progress; dozens of successful programs have already been implemented. From citywide conservation efforts to innovative rainwater capture, to successful and mutually beneficial agricultural solutions, we know these work. What’s more, we know they are the most efficient, cost-effective, widely available steps we can take right now to solve our supply/demand gap on the Colorado River without doing any harm, while continuing to grow our western economy.

Communities in the United States are being threatened by sewage overflows, flooding, polluted stormwater, leaky pipes, and at-risk water supplies. These threats are a result of our nation’s outdated water infrastructure and water management strategies, and their impacts fall disproportionately on low-wealth neighborhoods and communities of color that are already suffering from a lack of investment and opportunity. To solve this problem, we do not just need more investment in water infrastructure. We need a new kind of water infrastructure and management, and we need it in the right places. The solution is the equitable investment in and implementation of natural infrastructure. Naturally Stronger makes the case that if natural infrastructure is used in a more integrated water system, we can transform and restore our environment, invigorate the economy, and confront some of our country’s most persistent inequities.