San Francisquito Creek

Urban Oasis

Nearly hidden among a kaleidoscopic community of some four million Californians, San Francisquito Creek has managed to remain a remarkably undeveloped riparian oasis beneath scattered oak and redwood. The small stream that managed to escape urbanization as the boundary between the cities of Palo Alto, East Palo Alto and Menlo Park offers a sliver of hope for the most viable remaining native steelhead population in the South San Francisco Bay.

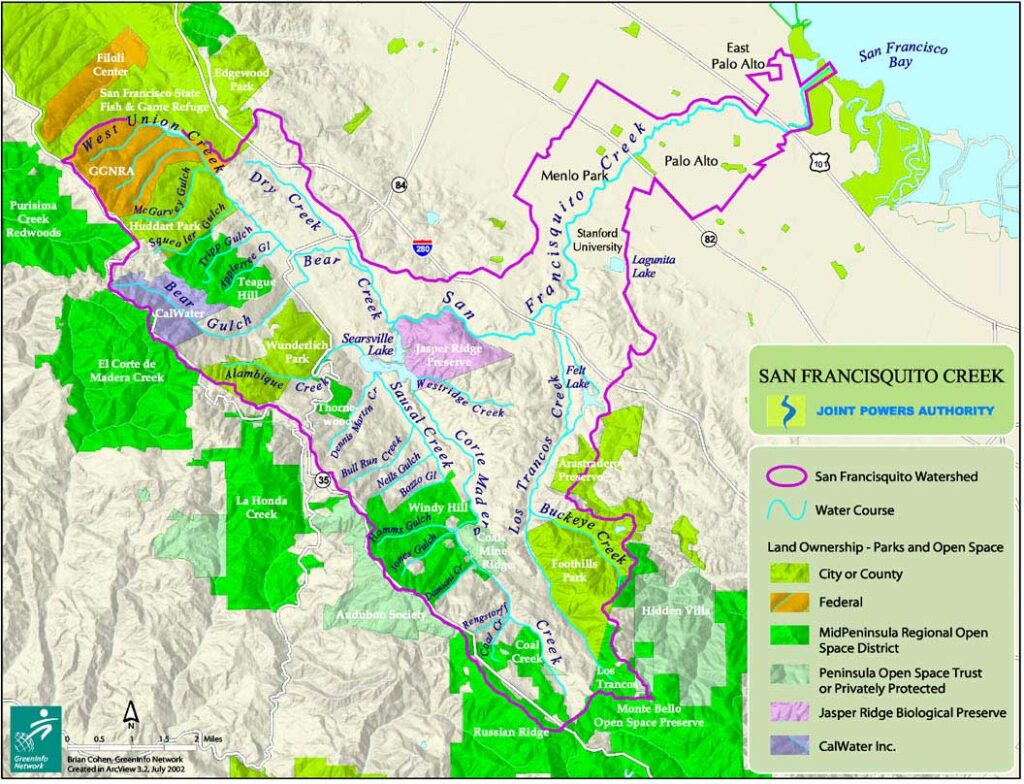

Fueled by winter rains and year-round springs, the creek’s 45 square mile watershed gathers dozens of small tributaries draining the Eastern Slope of the Santa Cruz Mountains. The short San Francisquito main stem, formed at the confluence of Bear Creek and Corte Madera Creek, flows for 12 miles east through Stanford University before meeting the southern portion of San Francisco Bay, the largest estuary on the West Coast.

Disagreements between bordering counties managed to preserve San Franciscquito as one of the only San Francisco Bay streams that is not confined to a concrete channel. Yet it could not prevent the construction of 65-foot Searsville Dam, the only thing standing between wild steelhead and access to 20 miles of native habitat upstream.

Evidence suggests coho salmon likely inhabited the stream at one time as well, alongside a host of native fish ranging from the Sacramento sucker, California roach, and three-spined stickleback to the no-longer-present Sacramento perch, squawfish, and seldom seen prickly sculpin. On the river’s edge, gray foxes have been documented near the mouth of San Francisquito Creek and on the Palo Alto Golf Course.

Did You know?

The tree from which Palo Alto takes its name, El Palo Alto, stands on the banks of San Francisquito Creek.

David Starr Jordan, the first President of Stanford University, included a rendering of a “sea-run rainbow trout from San Francisquito Creek” in the Pacific Monthly (now known as Sunset magazine) in 1906.

Originally called the Arroyo de San Francisco, San Francisquito Creek forms the boundary between San Mateo and Santa Clara counties, reflecting the original boundary between the Spanish Missions at San Francisco and Santa Clara.

The Backstory

Built more than 120 years ago to provide drinking water for Stanford University students, Stanford-owned Searsville Dam never served that purpose and is no longer needed for the school’s non-potable water supply. Yet it continues to cause significant harm to San Francisquito Creek and the fish and wildlife that depend on it.

Let's stay in touch!

We’re hard at work in the California for rivers and clean water. Sign up to get the most important news affecting your water and rivers delivered right to your inbox.

Steelhead trout were documented in the watershed as far back as the 1800s. The fish still migrate from the bay up to the barricade, but Searsville Dam serves as a complete barrier to their natal streams above. The dam blocks access to 20 miles of steelhead habitat upstream and reduces flows downstream, often blocking all flows in summer. It also drowned the confluence of five creeks and extensive wetlands, trading important riparian habitat for several species of birds, frogs, turtles, salamanders and other wildlife for a sediment-filled slackwater reservoir.

The reservoir is bad for native species because it has lower water oxygen levels, higher water temperatures, supports invasive species and algae blooms, and encourages the loss of water through evaporation. More than 90 percent of Searsville Reservoir is already filled in with sediment, eliminating its usefulness as a water storage facility. Unless Stanford takes action soon, the reservoir will fill in completely in coming years, posing safety risks to several nearby communities.

The Future

Despite an internal advisory committee at Stanford recommending in 2007 that Searsville Dam remain and the lake be dredged to maintain open water, the university is currently seeking additional analysis and a decision on dam removal is expected sometime in the next year.

But the writing’s on the wall. Already, San Francisquito Creek hosts the most viable remaining native steelhead population in the South San Francisco Bay, and the Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration named San Francisquito an anchor watershed for the recovery of wild steelhead trout in the bay. In 2014, a systematic study of more than 1,400 dams in California identified Searsville Dam as a high-priority removal candidate to improve environmental flows for native fish conservation.

It is time for Stanford to remove this obsolete dam to restore the health of the creek and secure the safety of its communities.