It’s hard to watch the news of the destructive fires in southern California without despairing for the safety and well-being of our loved ones, friends, and neighbors. Our hearts go out to all of you, as well as our impacted partners and supporters.

Today, many are rightly focused on the urgent need to protect themselves and their communities, and follow the guidance of emergency personnel who are putting their lives on the line to manage a dangerous and deadly situation. For those of us who are humbly embracing the gift of having time and space to think about recovery after this crisis, there are some truths on which we can ground ourselves to be more effective partners in helping the people and places we love.

We must acknowledge the reality of our situation, focus on facts, and not be misled by fiction. The climate crisis continues to deepen its impact on all people, regardless of identity, wealth, or geography. Today, parts of southern California are experiencing their driest winter season in the past 150 years. These exceptionally dry conditions are happening at the same time as extreme and prolonged winds, creating optimal conditions for catastrophic fires in our communities. Sadly, these kinds of disastrous fires are likely to become even more common as the effects of climate change become more severe.

We must also acknowledge our power to put solutions in place that will help people and communities right now and lessen the long-term impacts of climate change. Extreme fires not only threaten our homes and lives, but also the thing survivors need to live: clean, safe water for people and the environment. Fortunately, as we adapt to our ever-changing world, we know what we need to do:

We need to invest in water infrastructure for community safety. Healthy rivers are unmatched when it comes to providing clean, healthy water for people and nature, along with many other benefits. We know that the places in which we live are as much a part of our water infrastructure as the pipes that carry water to our homes. Stewarding rivers and the surrounding landscape through wildfire management – as opposed to suppression – is key to protecting our communities. Wildfire management does not only reduce the intensity of uncontrolled fires. It protects the land and rivers where water flows and the dams, pipes, and homes where water goes. Californians have already taken a critical step to make this work possible. Nearly 60% of voters approved $10 billion in state funds to pay for climate resilient solutions. These solutions include: drought, flood, and water supply projects; protecting communities from wildfire; and restoring and protecting natural areas.

Now, we can ensure those public funds can be accessed by continuing our support for the people and places who need them most. Whether through the largest dam-removal project in history or the largest meadow restoration in the headwaters of one of California’s most pristine drinking water sources, private-public partnerships have yielded unprecedented success in California to restore rivers and the clean, healthy water they provide for people and nature. We’ve done it before; we will do it again. Most importantly, we will do it together.

Rivers are wild and ever-changing; they are born to run free. And yet, more than 550,000 dams of all sizes choke rivers across our country. While many provide useful services including hydropower and water supply, many outdated, obsolete, and unsafe dams threaten rivers and communities. Dams contribute to the extinction of aquatic species, overall decline of river health, emission of greenhouse gases from reservoirs, and the destruction of Indigenous cultural sites and lifeways. Removing dams is the single most impactful way to bring a river back to life.

Low-head dams are hazards to public safety. These dams, while generally smaller in size, are not small in their impact or danger. Water continuously flows over the crest of these dams, which can create a recirculating hydraulic at the base of the dam which can entrap and drown people recreating near it. More than 1,400 fatalities have been recorded at these structures. Removing these structures is a permanent solution to the safety hazard they impose.

Since 1912. more than 2,100 dams have been removed to restore rivers. Free-flowing rivers promote healthy habitat for wildlife, reduce flood risk to communities, and support cultural traditions. Up to 85 percent of the 90,000 dams cataloged by the US Army Corps of Engineers are unnecessary, harmful, and even dangerous. We must remove thousands of them quickly.

Dams are infrastructure and we need elected leaders who are ready to address water infrastructure to restore rivers and protect public safety. We need laws that support the removal of obsolete and unsafe dams and ensure that dams staying in place are maintained to protect nearby communities. That’s why it’s important to #VoteRivers this November.

As the impacts of climate change stress our rivers, we need to restore them to their natural free-flowing state. Undammed rivers are better able to adapt to climate change while supporting healthy ecosystems and providing clean drinking water. When we #VoteRivers, we are voting for free-flowing rivers, for clean water, and for our future.

Beneath the concrete and asphalt, high rises and shops, playgrounds and schools, lies a hidden network of creeks, streams, and rivers. Some may flow underground through pipes, but they’re there. Now a growing number of cities are realizing just how important their forgotten waterways are — and how revitalizing them can lead to happier, healthier lives for all of us.

Here’s why urban rivers matter

Consider this: More than 80 percent of people in our country live in cities, and most of us live within a mile of a river. Yet many urban rivers and streams are unhealthy and polluted. They’ve been paved over and used as dumping grounds. This means a large portion of our population lacks access to clean, natural places crucial for health and wellness. Plus, polluted rivers don’t just impact their immediate surroundings — they impact entire ecosystems and communities downstream. In any interconnected system, damage to one part ripples throughout the rest.

Further complicating matters, most of our cities were built for weather patterns and populations of the past. Our infrastructure cannot handle the escalating flooding, sewage spills, and water pollution of today — let alone into the future, as climate change increases the frequency and severity of storms in many areas. These issues deeply impact Communities of Color, who have been excluded from decision-making processes and denied access to resources. Access to clean, reliable water and nature shouldn’t be a privilege — it’s a basic need for everyone.

To meet these challenges, we need to connect people to their rivers, rebuild our water infrastructure, making our communities more resilient and equitable. And we need to transform our cities into healthy, integrated parts of whole river systems.

So, what makes a River City?

A River City has thriving communities connected to its rivers, creeks, and streams. Clean water supports healthy people and healthy urban wildlife, flowing freely through a visible, above-ground river network with floodplains that allow water to spread out safely without risk to property or lives. The stream network is safe and accessible. Communities steward their resource and are engaged and leaders in issues related to water access and governance.

Over the past 25 years, we’ve worked with community leaders, water utilities, and city and community leaders in places like Milwaukee, Toledo, Tucson, Atlanta, and Grand Rapids — and we’ve learned invaluable lessons along the way.

Here are five criteria River Cities strive for:

- Clean: Healthy, clean waters flow through communities without trash or sewage, benefiting people and wildlife that rely on riverside habitats.

- Free: Creeks and streams flow freely without obstruction from dams, pipes, and fences.

- Safe: Communities have reduced flood risk and people feel safe visiting their local rivers.

- Fun: People have thriving natural places to enjoy in ways that are relevant to them, their friends, and family.

- For everyone: All communities have access to the benefits of healthy rivers and clean water, especially Communities of Color that do not have equitable access to nature and rivers. It also means that everyone is part of the decision-making about water and rivers in their cities.

From hidden to thriving — our work in Grand Rapids

Let’s explore what happens in a River City, using our work in Grand Rapids, Michigan, as an example.

STAGE 1: Discovery

To connect to a place, people must first discover the place. In Grand Rapids, after a series of intense storms, the city’s stormwater-management department went door to door in the Plaster Creek neighborhood, which lies near the most polluted creek in the Grand River watershed, to educate residents about issues with erosion and outdated infrastructure. The community was relieved to learn that there were solutions to the problem and was ready to work with the city to address the issues.

STAGE 2 Imagination

Once people are aware of their waterways, it’s time to envision. American Rivers’ local partners in Grand Rapids provided watershed education — and communities set priorities for greening their neighborhoods to improve the health of their creek.

STAGE 3: Momentum

This is where tangible progress begins. In Grand Rapids, a group of local nonprofits worked alongside community leaders to plan, design, and implement a set of “rainscaping” projects, such as rain gardens, bioswales, and native plants and trees, to mitigate flooding and improve the health of their urban creek. American Rivers, working with the city and local partners, created an innovative, market-based approach to incentivize private-property owners to install green infrastructure on their properties.

STAGE 4: Thriving

The final stage ensures long-term success can take root and flourish through community leadership. American Rivers is leading a group of local community leaders and nonprofits – including the West Michigan Environmental Action Council, Lower Grand River Organization of Watersheds, and Plaster Creek Stewards – to advocate for community needs, develop shared priorities, and work with city to fund and implement priority projects.

A river city renaissance

Whether by addressing pollution and flooding, improving access to nearby rivers and streams, or building resilience to climate change, American Rivers and our partners in cities around the country are helping urban communities rediscover and reimagine their relationship with their rivers and water. The next time you walk through your city, consider the hidden streams and rivers that may be beneath your feet. Through dedicated effort and community leadership, transformation of hidden creeks and streams into neighborhood assets that promote health and wellness is not only possible but inevitable.

Are you ready to be part of the River City transformation?

From Capitol Hill to mountain meadows to urban waterways, American Rivers is amplifying its impact nationwide. This progress is thanks to you and thousands of passionate advocates, partners, volunteers, and expert staff who contribute to our mission daily. Together, we’re building a future of healthy rivers and clean water for everyone, everywhere. Join us in celebrating our biggest success stories from the past year.

America’s Most Endangered Rivers® #1 spotlight drives action

New Mexico’s waterways face unprecedented threats, with nearly all rivers and wetlands at risk of pollution due to the loss of Clean Water Act protections. Yet recently, a significant breakthrough has inspired hope for the future. New Mexico allocated funding for a state program to regulate pollution and joined the America the Beautiful Freshwater Challenge. This ambitious initiative by the Biden administration sets a national goal to protect, restore, and reconnect 8 million acres of wetlands and 100,000 miles of our nation’s rivers and streams by 2030.

Our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® listing and partners’ leadership played important roles in raising public awareness and securing these positive steps forward. Looking ahead, we’re committed to supporting our partners as they gear up for a critical year of advocating to restore clean water protections in state laws and regulations.

Washington protects over 950 miles of pristine river systems

After years of advocacy by American Rivers and our local partners, the Washington Department of Ecology designated more than 950 miles of the Cascade, Green, and Napeequa river systems as Outstanding Resource Waters. These rivers are now protected for their cultural and spiritual significance to Tribal Nations, critical habitat for salmon and wildlife, and their role in providing a sanctuary of clean, cool water for species adapting to a rapidly changing climate.

$50 million boost for Flint River headwaters revitalization

We helped secure $50 million in federal funds to build a trail network that gives Southside Atlanta communities access to the Flint River headwaters greenspace, while also addressing stormwater flooding that threatens homes, businesses, and public safety. After a decade of work with local communities to draw attention to water challenges, this influx of funding is especially gratifying.

Yosemite’s groundbreaking meadow restoration effort

A groundbreaking restoration effort is underway in Yosemite National Park’s Ackerson Meadow, a critical biodiversity hotspot. American Rivers and our partners are restoring 230 acres of habitat for endangered wildlife, which will also improve water quality and boost groundwater storage capacity by an estimated 20 million gallons annually. Groundwater is an important source of clean, dependable drinking water.

Protecting thousands of miles of rivers across five states

Several of our highest-priority river protection bills advanced in Congress, bringing them closer to becoming law. These bills will safeguard thousands of miles of rivers and streams in Washington’s Olympic Peninsula, Oregon’s Owyhee River Canyonlands, Colorado’s Dolores River watershed, California’s Ackerson Meadow complex, and New Mexico’s Pecos River. The Owyhee bill would also move tens of thousands of acres of sacred lands into a trust for the Burns Paiute Tribe.

Philadelphia’s climate change leaders of tomorrow

Fostering Philadelphia’s environmental leaders of tomorrow, we partnered with Overbrook Environmental Education Center to launch an inspiring climate change career discovery program. Over three months, local high schoolers gained hands-on experience in diverse conservation skills, learning everything from assessing stream channels and flood risks to engaging with policy leaders, preparing them for environmental careers or college.

Grand Rapids advances green infrastructure

We received funding from the Grand Rapids City Commission to advance our sustainable approach to stormwater pollution. Communities of Color, who disproportionately feel the impacts of pollution, are important partners in this work. Our approach encourages installing natural features like rain gardens and bioswales, which filter and absorb excess water, contributing to a healthier, cleaner Grand River.

A co-published blog by American Rivers and the Getches-Wilkinson Center at Colorado Law.

The Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of 1968 has been the preeminent tool to protect free-flowing rivers in the United States since it was passed more than 50 years ago. Under the Act, rivers with “outstandingly remarkable scenic, recreational, geologic, fish and wildlife, historic, cultural or other similar values,” as well as their immediate environments, are protected from dams and other potential harms. In spite of its success, the Act largely omits Tribes, failing to give Native Nations the authority to designate, manage, and co-manage Wild and Scenic rivers within their own boundaries and on ancestral lands. Correction of this omission is long overdue.

A current example of this omission was brought to our attention through conversations with Indigenous community members along the Little Colorado River (LCR) in Arizona. The LCR was threatened in recent years by a series of pumped-storage hydropower projects proposed on Navajo Nation lands by non-Indigenous developers, and against the will of the Navajo Nation, Hopi Tribe, Pueblo of Zuni, and others who find the LCR culturally important. Historically, under the Federal Power Act, proposed hydropower projects have been given a preliminary permit on tribal trust lands by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) against the will of the Tribe whose land the projects would be located on. Indigenous community advocates understandably wanted to know, “What can we do to permanently protect the Little Colorado River from these unwanted hydropower projects?”

Designating a river under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act is a powerful defense against unwanted dams and diversions–it is the only designation that prevents new dams and diversions on designated rivers. The problem is that since Tribes were largely omitted from the 1968 Act, they were not given the power to designate or manage Wild and Scenic rivers, even on their own lands. That management power currently defaults to the National Park Service, even when a designated river is on tribal lands. To say that this is a disincentive for Tribes to utilize the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act to protect their rivers is an understatement.

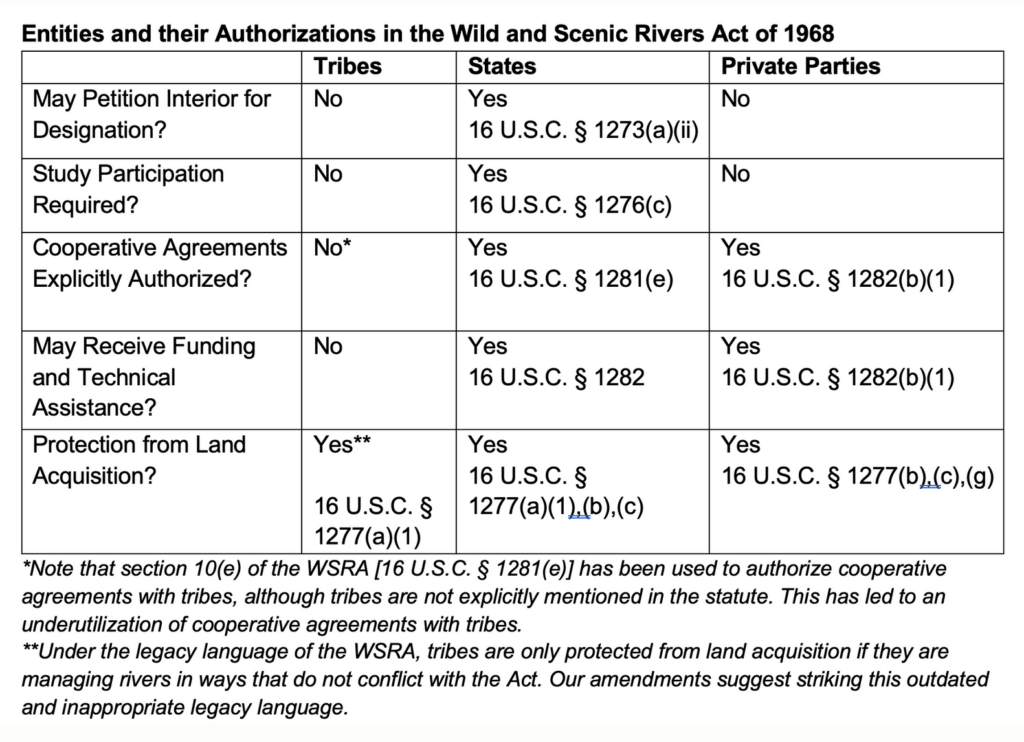

And that’s not all. As the Table below shows, Tribes don’t even have some of the powers that have been given to states and private parties under the Act, such as the ability to petition the Secretary of Interior to give Wild and Scenic protections to state-protected rivers, or the ability to receive funding and technical assistance, which both private parties and states can. Co-management/co-stewardship agreements and cooperative agreements are also not explicitly authorized for Tribes in the Act, which is a potential disincentive for federal agencies to explore such agreements with willing, interested, and knowledgeable Tribes.

As sovereign nations, Tribes should at least have the power that states and NGOs have regarding river designations. Tribes should be able to manage Wild and Scenic Rivers on their lands, ask the Secretary of Interior to include rivers protected by Tribes under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, be formally authorized to engage in co-stewardship agreements with federal agencies, and have the ability to receive funding and technical assistance when managing rivers on their lands.

Correcting the omission of Tribes in the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act remains long overdue. We heard from both legal scholars and tribal communities that creating a well-researched, draft proposal—which you can download here—would be the best way to begin an informed conversation. This is in no way intended to be a finished product, but meant to engage Tribes, advocates, and legal thinkers in what might be possible, and in turn help us make that a reality.

We also realize that proposing to amend a bedrock natural resources law is no small undertaking, and not without some risks. The structure of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act makes amending the Act easier and less risky than amending other similar laws. Currently, each new river designation is added to the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System through an amendment to the original Act, which means that a new Wild and Scenic designation by a Tribe that includes these proposed amendments would be all that would be necessary to implement them. Furthermore, the Concept Paper proposes extending existing authorities to Tribes through the addition of new sections in the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, not changes to existing protections that have been settled law for over 50 years.

In this way, and with your help, we not only propose to retain the protections that the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act has afforded outstanding free-flowing rivers across the county for the last half century, but to expand the ability for Tribes to utilize those same protections to safeguard free-flowing rivers of cultural and ecological importance into the future. Now is the time to address the omission of Tribes in the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act and other bedrock natural resources laws. Doing so would be a measure of restorative justice, while also benefiting Tribes and all life which depends on rivers.

Please download and read the Concept Paper and Draft Model Legislation, and let us know what you think. We look forward to hearing from you.

Click HERE to download a PDF of the Concept Paper and Draft Model Legislation. Please send feedback, questions, and comments to info@tribalwildandscenic.org or through our website www.tribalwildandscenic.org.

The Wild and Scenic Rivers Act Amendments Project was founded in 2021 by American Rivers, the Grand Canyon Trust, and the Getches-Wilkinson Center in response to Indigenous advocates seeking a tool to protect culturally and ecologically important rivers on Tribal lands from FERC-licensed hydropower projects. More input from Tribes, river advocates, and legal scholars is being sought for the next phase of this project.

I was recently camping with my son’s Boy Scout troop, near some caves in West Virginia. The caves were formed by a stream running down the mountain, that carved out a piece of limestone. The stream currently runs through several cow pastures, and we regularly found cow manure right next to the stream. While hiking through the cave with our guide, one of the Scouts decided to take a swim in one in the cave pools, dunking his head and playing around with some of the other Scouts — all good fun for a bunch of rambunctious kids. Unfortunately for him there is a lot of bacteria in cow manure (well, any sort of poop, really) and because he ingested some of the water while swimming, he ended up sick and throwing up most of the next morning.

Thankfully he recovered, but his experience with getting sick from manure or pollution getting into the water is more common than one would think. This past June, over 20 people swimming in Lake Anna, in Virginia, became ill due to E. Coli (the most common bacteria found in feces).

The irony is, many of our rivers are great places to recreate and swim in. Rivers are generally much cleaner than they were 50 years ago — prior to the Clean Water Act being passed — but a lack of investment in wastewater and stormwater infrastructure, and a growing rollback of clean water laws continues to prevent progress in cleaning up our rivers and streams; And in many cases actually making them worse.

The solution to cleaner water is a simple one — maintain and enforce common sense, scientifically supportable clean water laws, and invest in maintaining and modernizing America’s clean water infrastructure. Both of these solutions can only happen when we have elected officials who care about protecting our communities and want to invest in the infrastructure needed to ensure we have clean water. That’s why it’s important to #VoteRivers this November.

There are lawmakers, on both sides of the aisle, who understand the need for clean water. There are others who need to hear about why it needs to be a priority. We need more elected officials to stand up and champion the laws and the funding to keep our water clean.

It’s only when we all #VoteRivers that we can guarantee there will be clean water when you turn on your faucet, boat on your river, or, like the Scout I was with, swim in a stream.

With the election season in full swing, you are likely hearing a lot about something called “Project 2025.” Project 2025, a document produced by the conservative think-tank, the Heritage Foundation with the support of 30 other leading conservative organizations, is a suggested blueprint for the next conservative President. Regardless of your politics, there are a number of recommendations that have a serious impact on the environment and rivers and clean water, specifically. On the positive side, there are multiple suggestions for infrastructure investment, which would likely be a good thing for rivers. Unfortunately, the vast majority of the changes the blueprint proposes would have a decidedly negative impact on rivers.

In addition to broad cuts within the Department of Agriculture, the Forest Service, and the Department of Energy, among other agencies, there are specific changes called out that will have significant repercussions for rivers.

1. Within the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), it suggests eliminating the

- Office of Environmental Justice and External Civil Rights

- Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assistance

- Office of Public Engagement of Environmental Affairs

The plan also recommends to “review grant programs to ensure that taxpayer funds go to organizations focused on tangible environmental improvements free from political affiliation.” Project 2025 also recommends a “day one executive order” to stop all grants to advocacy groups. And on water specifically, Project 2025 recommends codifying a “navigable water” clause to “respect private property rights.”

What this means for rivers: This means that federal funding currently going to conservation organizations, like American Rivers or those on the ground removing dams to restore rivers, could be held up or eliminated. Weakening federal safeguards for clean water means that it will be up to the states to decide, meaning access to clean water will be depend on the politics of one’s state, not necessarily what is needed for healthy communities or ecosystems. And because rivers don’t stop at state borders, pollution could increase everywhere. Many federal safeguards currently in place to protect rivers and clean water, especially in communities that have traditionally been under-served due to their race, cultural, or income makeup, will no longer be enforced.

2. Project 2025 suggests lifting the ban on fossil fuel extraction on federal lands, which would put countless miles of rivers and streams at risk.

What this means for rivers: Putting climate change concerns aside for the moment, with any new fossil fuel extraction, the risk of accidents, leaks, and spills goes up considerably. And as we have seen numerous times before, one accident can damage a river and clean water supplies for decades. Further, the headwaters of many rivers in the U.S. are found on national public land. More pollution, means more risk to the literal places where rivers are born, and that will have impacts to everyone who uses it as a water source.

3. Project 2025 calls for the dismantling of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) by moving some responsibilities to other agencies and privatizing other duties. The National Marine Fisheries Service would be streamlined and some duties transferred to the Fish and Wildlife Service, and the “America the Beautiful” and “30×30” programs withdrawn.

What this means for rivers: The NOAA website says it best:

“From daily weather forecasts, severe storm warnings, and climate monitoring to fisheries management, coastal restoration and supporting marine commerce, NOAA’s products and services support economic vitality and affect more than one-third of America’s gross domestic product. NOAA’s dedicated scientists use cutting-edge research and high-tech instrumentation to provide citizens, planners, emergency managers and other decision makers with reliable information they need, when they need it.”

Without a central agency monitoring our climate and weather, and informing the many parts of our government that need that data, we run the risk of being unprepared for the next hurricane, storm, flood, or drought. We already know that climate change impacts every drop of water in our lives. Ignoring this fact threatens our safety and way of life on Earth.

4. With the Department of Energy (DOE), Project 2025 reinforces support for fossil fuels by encouraging more extraction and streamlining public safeguards.

What this means for rivers: We already know that a reliance on fossil fuels will continue to warm our world and intensify floods and droughts. With more drilling and fewer safeguards, threats to rivers and their wildlife and communities will increase.

5. The plan recommends moving the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) from the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to the Department of Interior or Department of Transportation, and suggests phasing out programs like the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) to private insurance. Disaster preparedness grants would be changed to only go to states – NGOs, Tribal governments, and localities would need to go through State governments for funds.

What this means for rivers: As floods become more frequent and severe, FEMA and the resources it provides become more and more vital. Moving these critical emergency response tools away from an agency that already has the national infrastructure set up to respond when needed would be unnecessarily putting lives at risk. Eliminating federal support programs in favor of state or — even worse — private, control, assures the same vulnerable communities that historically have suffered the most will continue to be under-served, and will have a harder time recovering from the next disaster.

Interested in doing more for rivers? Download our election guide to better understand the threats rivers face in this election. Or join us right now in taking action for clean water by asking Congress to increase federal protections for all streams and wetlands. This is our chance to make a difference!

On Friday, June 28th, the Supreme Court overturned the Chevron doctrine in a 6-3 decision in Loper Bright v. Raimondo. In doing so, the Court unleashed a new era of uncertainty for the environmental regulations that protect rivers and clean water. Named for the landmark case Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc. (1984), the Chevron doctrine has shaped the way courts defer to administrative agencies’ interpretations of ambiguous statutes for the last forty years. The doctrine allowed agencies to take a pragmatic approach to complex regulatory challenges by relying on agency expertise rather than explicit Congressional direction.

Judicial review has long been a part of the regulatory rule-making process in the highly-litigious environment of the United States. Typically when reviewing agency regulations, the courts first determine whether or not Congress has spoken directly to the issue in question. If the Congressional intent is clear, the courts follow that intent. In cases of Congressional ambiguity, however, the Chevron doctrine required judges to defer to the expertise of agency staff. The reasoning for this deference was the recognition that agency staff often possess specialized knowledge and expertise in their respective fields.

The overturn of the Chevron doctrine now disrupts this delicate balance between judicial oversight and administrative expertise by eliminating deference to agency expertise and allowing the courts increased discretion to interpret, according to their individual judgment, whether agency regulations are permissible. Critically, it limits the role of experts in the development of regulations in favor of statutory clarity and judicial review by non-experts.

The end of Chevron deference will have a notable impact on the environmental protection of rivers, wetlands, and streams. Particularly at issue will be the scope and interpretation of the Clean Water Act (CWA). Enacted in 1972, the CWA is the cornerstone of federal environmental law aimed at restoring and maintaining the integrity of the nation’s waters by regulating the discharge of pollutants and setting water quality standards. Regulatory agencies, including the Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, are charged with enforcing the provisions of CWA. For nearly half a century, these agencies have had broad latitude to interpret the CWA and enforce a reasonable regulatory regime. However, this power of interpretation has now largely been stripped away from the agencies and applied to the judiciary.

Now more than ever it is important for Congress to take action for rivers and clean water. With agencies now constrained in their ability to broadly interpret the law in favor of environmental protection, Congress must make clear its intentions to protect clean water for all. The end of Chevron deference is a call for Congress to write laws better and more explicitly as well as an opportunity for states to step up their own regulatory regimes, filling a gap now found at the federal level.

While the full impact of the overturn of the Chevron doctrine remains to be seen, regulatory policy will no doubt be a subject of intense scrutiny and debate for the foreseeable future. As federal agency regulations continue to evolve and face scrutiny in courts, the interpretation and enforcement of environmental laws like the CWA will continue to undergo changes, impacting how well the nation is able to address water quality and environmental protection for our rivers, wetlands, and streams.

This is a guest blog by Tim Palmer.

In river conservation we strive to make our work and stories known, and we sometimes succeed. But when rivers flood, they always make it into the news.

In what has become a milestone in the history of American flooding, and of our responses to it, a deluge justifiably called the “Great Flood” of the Mississippi held the nation rapt in 1993 with images of mayhem and misery. But American Rivers’ then President Kevin Coyle and his media master, Randy Showstack, knew that the tale of misfortune, along with the response of mercy and recovery, was not complete without asking the hard but mandatory questions: What should we be doing differently? What can we accomplish to not just alleviate the losses but to stop them from continuing? Furthermore, how can the life and health of rivers be better reflected in the stories we tell and paths we take following a flood?

Responding to these questions, American Rivers launched an insightful campaign that looked toward actually solving the flooding problem, focusing on a brighter future rather than a tragic past. Scoring the attention of national talk-show host Larry King, plus big newspapers nationwide, Coyle and Showstack urged recognition that floods are natural events destined to reoccur no matter how much we try to stop them. Our response must be to avoid damage in the future rather than just pay for it after the harm is done.

In fact, while billions of taxpayer dollars have been spent building dams to stop floods from occurring, and more billions spent building levees to keep floods away from homes, and multi-billions more subsidizing people to rebuild in the aftermath, relatively little has been spent to protect floodplains from new development that will otherwise aggravate future disasters, and little has been invested to help people relocate away from deadly hazards whenever the flood victims are willing to go.

The Natural Resources Defense Council recently found that every $1.70 our government spends helping people move away from flood hazards has been matched with $100 helping people stay in the danger zone by paying for relief, rebuilding, and subsidized insurance, all in order await the next flood. None of that covers the cost of the dams and levees that are too often ineffective or even hazardous with risks of over-topping and failure in the largest floods—not to mention the well-known damage that dams and levees often do to the nature of rivers.

The challenge to public policy here goes far beyond practical and pragmatic issues of spending, and directly into the realm of river conservation with goals of healthy rivers in mind. Floods, after all, are natural events that ultimately cannot be stopped by dams and levees. Floods are necessary phenomena that shape streams with essential pools and riffles. Floods recharge groundwater that half our population depends upon for drinking supplies, that nourish riparian corridors as the most important habitats to wildlife, and that create conditions needed for fish to survive and spawn. Rivers need floods and nature needs floodplains.

High-water problems have floated to the top of public agendas ever since the Flood Control Act of 1936, which unleashed a fifty-year frenzy of dam building on virtually every major river in America. Seeing the futility of relying solely on dams-and-levees, Congress in 1973 bolstered a latent national flood insurance program with incentives for local governments to qualify their residents for subsidized flood insurance provided the communities also zone lowlands to limit development from the most hazardous areas. Fast forward to the 2000s, and we’re promoting “natural solutions,” such as watershed management and floodplain reconnection. In spite of it all, damages continue to rise with greater losses occurring from continuing disasters.

And now the floods are increasing. High water is becoming more intense, more frequent, more widespread. The US Global Change Research Program in 2018 forecast precipitation to grow up to 40 percent across much of the country. Virtually all reputable sources report that flooding will increase with the increasing warming of the planet’s climate. It has to; every 1 degree rise in atmospheric temperature allows the sky to hold 4 percent more water, and it all comes back down as rain or snow.

A long list of sensible approaches have succeeded in denting the armor of this problem. The metro government of Nashville has sustained a floodplain management and relocation program for decades and succeeded in halting development on high hazard floodplains while helping 400 home owners voluntarily move to safer terrain. Charlotte, North Carolina, and Tulsa, Oklahoma, have similar initiatives. Lycoming County, Pennsylvania succeeded in getting all fifty-two of its local municipalities to enact floodplain zoning and launched a buy-out program that continues, helping people move to drier ground. Napa, California transformed a conventional proposal for higher levees to a plan that expanded acreage dedicated to flooding and that created new parklands along the river. The Susquehanna Greenway Partnership strives to protect recreational greenways along hundreds of miles of the East Coast’s largest waterway.

My personal engagement with flooding began at the height of the Hurricane Agnes Flood in Pennsylvania when I lived in the danger zone at ground-zero of that storm—one that caused unprecedented flooding across eight states. Working as a county planner back then, my job was to figure out what should be done differently to not just recover from the disaster but to avoid the next one. In the aftermath I saw how dams had failed to contain the flood crest, how levees had ruptured when we needed them the most, and how post-flood relief was costly, inadequate, and useless in coping with the floods of the future. There had to be a better way. I set out on a search to find that path, and then, fifty years later, to write a book about this fascinating story of nature, community, culture, economics, engineering, climate, crisis, and always of rivers.

American Rivers led the way toward better understanding back after the Great Flood of 1993, and a similar mission continues with the organization’s current floodplain restoration goal of “reconnecting 20,000 acres of floodplains to their rivers” during the next few years. Doing this will allow flood waters to spread out, benefiting freshwater ecosystems and reducing damage to homes, businesses, water lines, roads, and other infrastructure.

Rivers make the news when they saturate the homes where people live, but that’s the bad news. The good news is that floodplains can be protected for when rivers do overflow, and so that our streams can deliver the benefits that only high water can bring, all provided we are not living in the path of the greater floods to come.

Former American Rivers board member Tim Palmer is the author of Seek Higher Ground: The Natural Solution To Our Urgent Flooding Crisis, published by the University of California Press, 2024, and other books about river conservation. See www.timpalmer.org.

Yesterday at the White House, the Biden Administration announced bold and exciting new national goals for the protection of rivers and freshwater resources as a part of its America the Beautiful Freshwater Challenge. These goals include protecting and restoring 8 million acres of wetlands and 100,000 miles of rivers by 2030. These are the most ambitious benchmarks for clean water and rivers put forth by any administration, and build on unprecedented new protections and clean water investments under the Bi-Partisan Infrastructure Law. These would be a major contribution to American Rivers overall goal of protecting 1 million miles of rivers across the country.

The Administration announced these new goals at a Water Summit held at the White House that brought together roughly 100 inaugural signatories to the Freshwater Partnership, a collaboration of mayors, tribal leaders, state representatives, philanthropists, and members of the conservation community, including American Rivers. The Summit dug into the meaty freshwater issues facing communities that rely on the Mississippi, the Hudson, the Great Lakes, the Columbia, and the Klamath. I was fortunate to participate on behalf of American Rivers and was blown away by the collective vision, passion and commitment shown by the Administration and participants. The shear scale of what the Biden Administration and communities are doing to invest in and protect clean water nationwide was an inspiration.

Not surprisingly, the Summit included very strong Tribal representation, including members of the Confederated Tribes of Warms Springs in Oregon, the Yurok from California, and the Gila River Indian Community in Arizona. At the outset Chairman Gerry Lewis of the Yakama Nation led the Summit in a tribal prayer and reminded us that water is life, a “first food” worthy of the highest honor in their ceremonies honoring the Creator. The Chairman noted that the Yakama Nation has already been working hard to meet ambitious conservation goals, having protected over 2,000 miles of rivers, 14,000 acres of wetlands, and reestablished connectivity for 200 miles of rivers through barrier removal.

There was also a number of mayors from Louisiana, Michigan, Wisconsin, and New York who participated in the Summit and spoke about the ways they are working on the front lines of the fight to protect nature and put federal infrastructure funding to work to provide access to clean water for all Americans. Mayor Torrance Harvey from Newburgh, New York, 60 miles north of New York City, spoke eloquently about the importance of access to clean water as not only a public health issue, but also as a public safety issue. We should invest in clean water like we invest in other public safety needs, such as firefighting or law enforcement, since it too is a fundamental aspect of our community’s well-being.

Two young river leaders, Keeya Wiki and Ruby Rain Williams from the Klamath River Basin in northern California, stole the show with their impassioned plea for why we must act to protect rivers and support youth involvement in the outdoors. With leaders like the two of them the future of river conservation is in good hands.

Safe to say I was incredibly inspired by all of these speakers and thrilled to participate in this unprecedented event kicking off the Administration’s expanded commitment to freshwater protection nationwide. The Summit really reflected the full array of conservation and investments needed to meet the biodiversity, climate, and cultural crises that face us all. Along with all the mayors and Tribes who attend the Summit, American Rivers is committed to doing whatever is necessary to achieving these freshwater conservation goals and ensuring clean water for all.

Though a century of damming has had one of the largest impacts on the health of the Klamath River, its ecosystems, and the fish and wildlife that depend on them, they are not the only obstacles the river faces on the road to recovery. It is difficult to understate the ecological significance of the four dam removals on the Klamath River: with over 400 vertical feet scheduled for removal in 2023 and 2024, its sheer scale is why dam removal is such an important start to the river’s recovery. Now that the dam removals are underway, we are shifting our focus forward to improve the health of the entire watershed, from the meadows of the Upper Klamath downstream to the estuary at the Pacific and the tributaries in between. Below are three post-removal restoration priorities that are key to watershed-wide recovery.

- Establishing environmental flows: Environmental flows (water allocated for ecosystems, rather than directly for human use) are a big deal in the Klamath and its tributaries. An undammed river is not necessarily a wild river, and we need to designate water for the environment to enhance the health of our ecosystems. In the Klamath watershed, some of the undammed rivers like the Scott (which is vital for native fish and wild salmon) run dry year after year because of agricultural and municipal water use. No single person or place is responsible for diverting the river; but together, all these small diversions are creating severely degraded and unhealthy rivers. Setting environmental flows help people know when and where water is available for diversions, and when and where it is critical for a healthy river.

- Restoring the Upper Klamath: Though four major dams are being removed, the Klamath River will not be free-flowing. The upper river remains dammed, with Keno Dam and Link River Dam still in place. The water that runs through these dams is managed to maintain a steady water supply for agricultural water users and wildlife refuges, and the landscape around the river has mostly been converted for agriculture use. These developments have eliminated most of the wetlands in the headwaters that were crucial for shallow groundwater storage and improved water quality in the river, and many waterways run through many active working ranches and farms. While land management and water management have improved substantially from earlier practices, the damage done in previous decades remains. We need to scale stream restoration and habitat restoration so we can promote watershed-wide river health. Some of this work has already started, but more work remains. By working with landowners and rightsholders to reconcile how people live and work with rivers, we can provide a model of healthy rivers and healthy communities

- Restoring the Klamath’s Headwaters: The headwaters of the Klamath extend far beyond upper Klamath region in Oregon. The headwaters of tributaries like the Shasta, Scott, Salmon, and Trinity rivers play a vital role in the overall health and biodiversity of the Klamath watershed. Healthy headwaters create healthy rivers, and as the Klamath flows downstream, it draws water from the surrounding landscape. But with larger and more destructive fires fueled by climate change, water quality can be seriously impacted. As wet mountain meadows dry, they lose the capacity to store and filter water. These processes are critical to river health. We are taking the lessons learned from our meadow restoration and forestry management work in the Sierra Nevada with the Sierra Meadows Partnership (SMP) and integrating them into our work in the Klamath. American Rivers has joined the core team of the Klamath Meadows Partnership (KMP), a coalition dedicated to scaling the sort of work that can build towards resilience in Klamath’s headwaters and a more resilient future across the region.

Until now, American Rivers has trained our focus on dam removal, and for good reason. Now we are transitioning to the next chapter: post-dam removal river restoration. This work truly takes a village and depends on the combined efforts of Tribes , private philanthropy, the state and federal government, NGOs, private landowners, and impacted communities. To learn more about how to get involved as we look towards our collective future, please reach out to Pat Callahan at pcallahan@americanrivers.org.

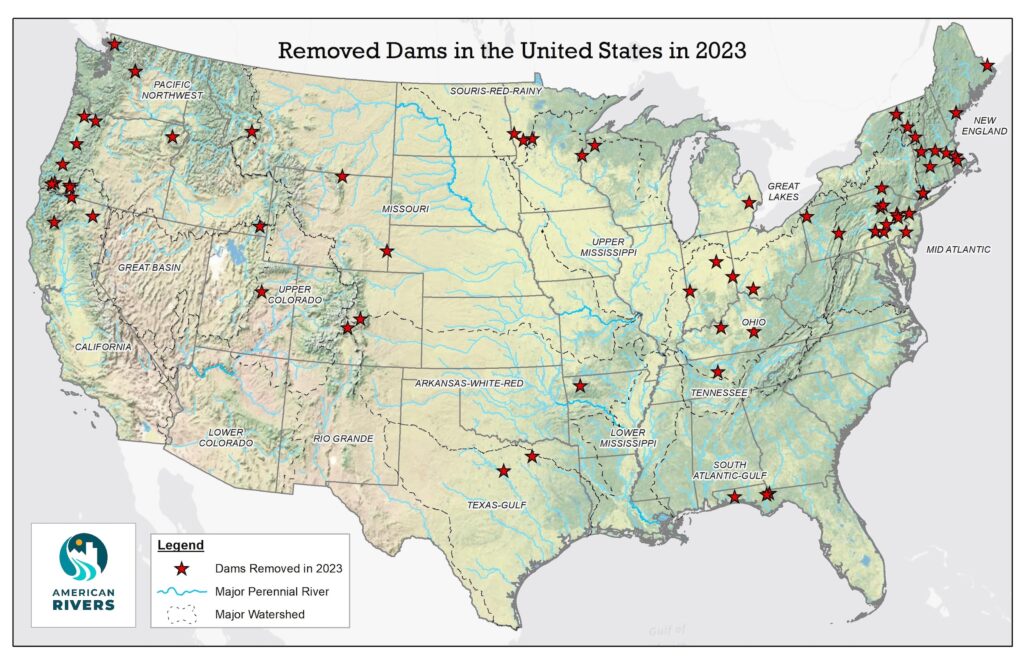

As many have heard by now, 2023 was a major milestone year for dam removal in the U.S., with the initiation of the largest dam removal project in the country on the Klamath River in California. However, you may not have heard about the 79 other dams that were removed, reconnecting 1,160 upstream river miles. These projects reestablished migration corridors, made natural and human communities more resilient to climate change, improved access to habitat to promote biodiversity, eliminated safety hazards and maintenance costs, enhanced access to rivers for local communities, reestablished natural processes for healthy rivers, and many other benefits.

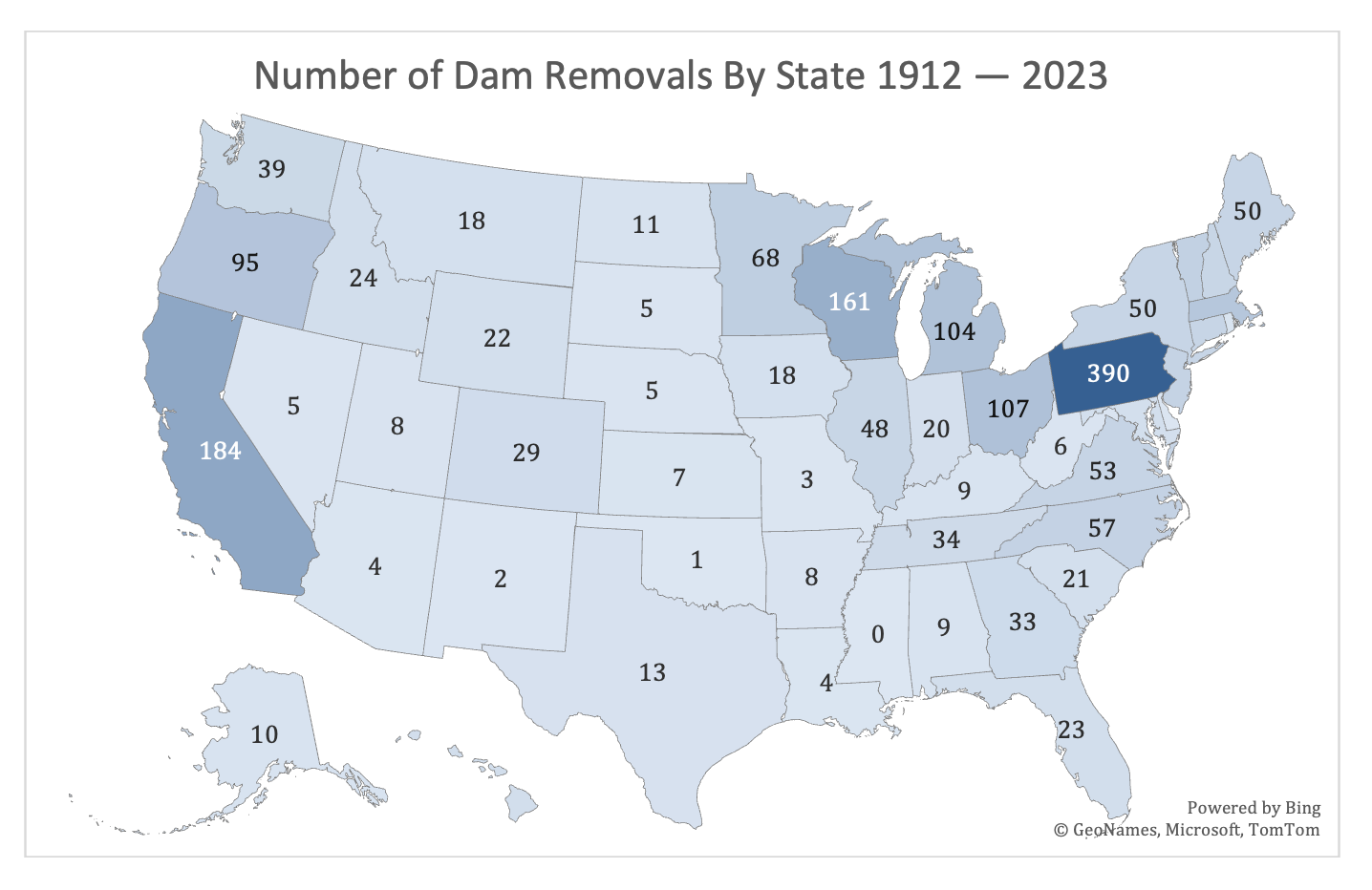

As a nationwide leader in river restoration, American Rivers tracks dam removal trends and maintains a national dam removal database. A total of 2,119 dams have been removed in the U.S. since 1912.

In 2023, the states leading in dam removal were:

Pennsylvania (15 removals)

Oregon (9 removals)

Massachusetts (6 removals)

Twenty-two other states also removed dams in 2023: Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Idaho, Indiana, Kentucky, Maine, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Vermont, Washington, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

Pennsylvania still leads the country in all time number of dam removals at 390!

As Katie Schmidt recently shared, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law has promoted a bump in removals, helping with at least 18 of this past year’s projects. We need more funding like this in order to address the backlog of dilapidated infrastructure out there.

Many dams in the U.S. are no longer serving the purpose for which they were constructed and/or are deteriorating and in need of significant repairs. Dilapidated dams pose safety hazards and threaten the resilience of human and natural communities. This year, the National Low Head Dam Inventory Task Force, in partnership with the Southeast Aquatic Resources Partnership, catalogued hundreds of thousands of dams, bringing the national total to more than 531,000 dams. American Rivers is building a movement to remove 30,000 dams by 2050, in partnership with communities, Tribal Nations, and state and federal agencies, to ensure that rivers can continue to sustain life.

You can read more about some of the projects completed in 2023 in our annual dam removal summary.

If you work on dam removals in some capacity (practitioner, regulator, researcher, contractor, community advocate, etc.), we invite you to join our National Dam Removal Community of Practice. We will be working with this community to build out strategies to get to 30,000 dam removals by 2050. If you aren’t heavily involved in dam removal, but you still love the idea of it, we would appreciate your financial support to keep the lights on.

Lastly, if you want to hear more about some case studies from the 2023 cohort of dam removals, please consider joining us for a webinar on February 21 at 3PM ET. You can register here.

We can make this happen together!