The Columbia River Basin was once the world’s largest producer of salmon and steelhead, with an estimated 10-16 million adults returning from the Pacific Ocean each year to spawn in the basin’s freshwater rivers and streams prior to 1850. Today we evaluate overall returns based on trends due to the high variability among species, populations, habitats and myriad other factors and metrics from one year to the next. What is clear in those trends today is that salmon and steelhead overall are returning to the Columbia Basin now at an alarmingly small, often single-digit percentage of historical abundance. Sometimes lower. Thirteen populations are listed for protection under the Endangered Species Act (ESA), including four populations in the Snake River Basin, the Columbia’s largest tributary that historically produced the most salmon. The Snake Basin’s upper reaches in north-central Idaho hold the largest, best-protected salmon habitat in the lower 48. So why, when we have the habitat, do we continue to see such a decline? Let’s dig in.

As the effects of climate change worsen, the actions we take now to build, restore and fully realize resilience in salmon and steelhead habitats become all the more vital to their ability to survive.

Hot water kills salmon and steelhead—period—and a warming climate means warming water. The changing climate’s impacts on salmon and steelhead are amplified in heavily dammed systems like the Columbia and Snake, where giant lakes of impounded water behind dams warm quickly in summer and early fall months—and stay warm. The result is essentially massive, warm-water migration barriers in the mainstem Columbia and Snake, often lethal to fish that try to get through. Natural oases of cold water associated with gravel bars and groundwater upwellings that migrating fish have historically relied on to hopscotch through the warm seasons disappear. Major fish kills are becoming more common too. In 2015 for example, 96 percent of the Snake River sockeye died trying to navigate through lethally warm waters to cooler tributaries and spawning grounds upstream.

So why all the focus on the Snake? The Snake River’s importance to the overall Columbia Basin salmon and steelhead recovery picture—and climate—can be broken down into two basic points: 1) Snake River tributaries in watersheds like the Salmon, Selway and Clearwater in Idaho offer some of the most intact, productive and climate-resilient salmon and steelhead habitat anywhere on the West Coast; and 2) In order to fully realize the vast recovery potential within these habitats, salmon and steelhead have to be able to reach it—alive—and to migrate back out to the ocean as juveniles.

Evidence indicates that currently, in places, they are not: one US Forest Service study in the pristine Middle Fork Salmon River found Chinook salmon redds in 2019 were just 0.7 percent of those from the 1950s and 60’s. The four federal dams built on the lower Snake between 1955 and 1975 are taking their toll. What used to take a few days to a week for a salmon to make its way to the ocean, can now take up to a month. Those four dams make the lower Snake River warm, slow and treacherous, and that means returning salmon struggle to reach the upstream habitat and smolts are less able to make their way to the ocean. Every year a warming climate means the water impounded behind the four dams is warmer and salmon increasingly cannot survive the slow-moving warming water.

Scientists with conservation group Trout Unlimited forecast that by 2080, 65 percent of the “coldest, most climate resilient stream habitats on the West Coast” will lie in the Snake River Basin. Restoring a free-flowing lower Snake River represents the surest way salmon, steelhead and the region can take fullest advantage of the recovery potential we have right now, both in access to and from those intact tributary habitats that are largely protected as Wilderness and Wild and Scenic Rivers and in restored mainstem habitats as well.

Many also point to ocean conditions as a driving factor for salmon declines. While we need to address climate change and resilience on all fronts, the Fish Passage Center recently reported, “…the number of smolts that enter the ocean is dependent on freshwater survival and management strategies that result in the highest freshwater survival possible, because not even the best ocean conditions can resurrect a dead fish.”

In short: we’ve got to clear the path for wild Snake River salmon and steelhead recovery and resilience and all signs point to the Snake-Salmon-Clearwater basin in Idaho.

Well before 2021, the Northwest had moved beyond the idea that the economy and environment were distinct sectors to be considered separately, somehow independent of one another. The Northwest has long understood the two are interconnected and for our region, that is a good thing. The integration of the economy and the environment is one of the Northwest’s greatest strengths and competitive advantages, and it is one we’ll be wise to rely on even more into the future.

It’d be easy to call our rivers the Northwest’s greatest natural strength and most valuable asset if we didn’t have so many others too. Rivers are integrated into nearly everything we do here, from fishing and boating to energy and agriculture to transportation and tourism to drinking water and showers. And lots more. The Northwest’s river-related economic portfolio is, to say the least, robust, and diverse. Right now, is as good a time as any to make sure the investments we’re making in stewardship of Northwest rivers are providing the highest return possible.

Sound investments in the health of our rivers—especially those that could use some help—often bring rapid returns that continue to grow over time: improved health of the river and everything that depends on it; greater capacity to support local river-related business; and river restoration jobs can provide a boost to the local economy, to name a few. River restoration today is its own industry; it’s growing, it’s got good jobs, and it reaches all corners of the region. The University of Oregon has studied the economics of restoration extensively and says that every $1 million spent on watershed restoration results in an average of 16 new or sustained jobs along with $2.2 to 2.5 million in total economic activity. Even better, 80% of project funds invested stays in the county where projects are located.

Ensuring the health of Northwest rivers is not just the right thing to do for our ecosystems, healthy rivers also support other, long-time, bedrock economic sectors of our region and help them grow. According to the American Sportfishing Industry, recreational fishing in Oregon, Idaho and Washington combined generates more than $5.3 billion annually in economic benefits and supports 36,740 jobs. The Outdoor Industry Association says that fishing and water-related recreation generates over $175 billion in retail spending annually, and more than 1.5 million jobs nationwide. A good chunk of that is in the Northwest, naturally.

When we fail to be good stewards of our rivers, that tends to harm livelihoods and local economies. Oftentimes it is the smaller towns and tribal communities that get hit the hardest. In 2019 on Idaho’s Clearwater River, for example, where sport fishing brings an estimated $8 million a month to local communities, fishing shut down due to critically low numbers of steelhead. Fisheries that Nez Perce families rely on for subsistence closed down too, on both the Clearwater and the Snake. As a region, we can do better.

The Northwest is blessed with a wealth of great rivers. The region’s traditions, cultures, economies, and identity are supported by them. Taking care of Northwest rivers today is one of the smartest investments in our future we can make.

The rush to build a massive open-pit gold mine in the headwaters of one of Idaho’s most important salmon-spawning rivers has hit a roadblock.

On July 1, the developer of the controversial Stibnite Gold Project announced that the US Forest Service would delay a final permitting decision, originally anticipated to be released in December 2020, for at least another two years in order to allow time for additional environmental analysis to be completed.

Perpetua Resources, a mining corporation that is majority-owned by a New York hedge fund, has been seeking regulatory approval to move forward with an enormous mountaintop removal operation in the headwaters of the South Fork Salmon River. If allowed to proceed, the Stibnite Gold Project would be one of the largest gold mining operations in the nation and adversely impact one of the country’s most cherished rivers forever. The project plans to create immense craters where mountains once stood, bury pristine headwater streams and valleys on the Payette National Forest, and create a 450-foot-high earthen dam that would hold back a 400-acre toxic tailings reservoir that must be maintained into perpetuity.

The South Fork Salmon River is a national treasure that provides critical spawning habitat for the longest distance, high-elevation salmon migration on earth, as well as world class whitewater recreation, fishing, and opportunities for solitude. The South Fork and its cold, pristine headwaters support a growing and sustainable recreation economy, supply clean water for agriculture and communities, and help downstream river ecosystems be more resilient to our changing climate. The proposed mine site is also located within the ancestral homelands of the Nez Perce Tribe, whose treaty reserved right to access the area would be restricted for decades if approved.

For three out of the past four years, American Rivers has named the South Fork Salmon River as one of America’s Most Endangered Rivers®. This past fall, we joined the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), concerned citizens, and many others who called on US Forest Service to conduct a supplemental environmental analysis to address missing information and serious threats to water quality that have not been properly evaluated.

While it’s good news the US Forest Service will now evaluate an amended plan the company submitted in December, slowing down the permitting process yet again, American Rivers believes it is critical that the supplemental review must also address the suite of substantive concerns that have been raised by the Nez Perce Tribe, EPA, conservation groups, and others.

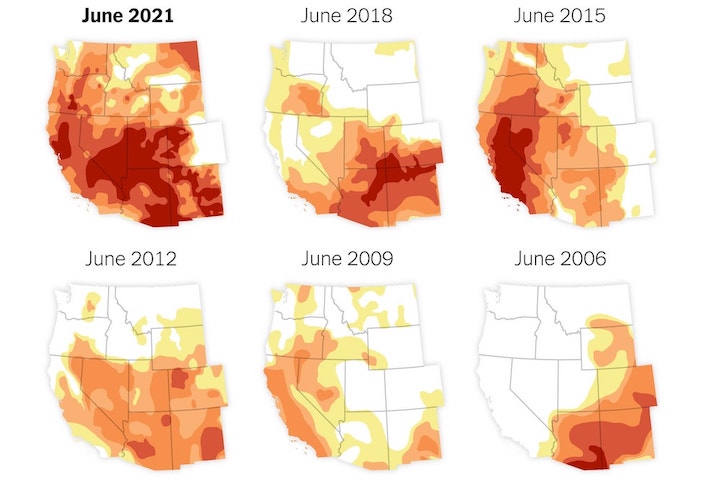

If 2020 and the global COVID-19 pandemic will be remembered for shining a light on the realities of our connected world, then the summer of 2021 will be remembered for the mirror it held up to the realities of a warming and drying future for water in the Colorado River Basin.

We’re on the brink of the federal government declaring a water shortage, Lake Mead and Lake Powell have plummeted, and any sign of replenishing flows is precarious at best. But unlike COVID-19, this shortage has been on the horizon for decades. Water managers, scientists, and non-profits like American Rivers are sounding the alarm (and have been), about the realities of a simultaneously drying and ever-more-demanding West.

Concerns about drought and impacts to everything from fish to farmers are not political statements—they’re true ones, backed now by a bounty of science. The harsh reality of these truths is that the scale and pace of climate-related changes in the Colorado River Basin pose a gargantuan challenge, unprecedented in the history of water management.

It’s not that we haven’t made attempts to respond. Certainly, we have. Conservation efforts have long centered on balancing supply and demand, but these are in-the-moment and short-term responses to a very long-term challenge. What we need now is forward thinking strategies to adapt, respond to, and mitigate the steady, compounding, and extreme risks of climate change to economies, communities, wildlife, landscapes, and at the root of all of it—the rivers we rely on.

At this precipice, our future demands that we invest our time, energy, and financial resources boldly and immediately in strategies that will work—that will build for all of us the kind of future we want for our children.

A recent report to which American Rivers contributed entitled “Ten Strategies for Climate Resilience in the Colorado Basin,” authored by Martin & McCoy and Culp & Kelly, LLP, outlines those strategies (see below). To arrive at this list of top ten, report authors asked:

- Could the investment help the Basin adapt to ongoing climate shifts?

- To what extent would the investment reduce pressure on existing water supplies?

- Would the investment help mitigate climate change?

- Could the investments strengthen economic resilience in communities?

The resulting top 10 investment strategies for a more resilient future are:

- Forest Management & Restoration – Prioritizing forest management and restoration to maintain system functionality and biodiversity

- Natural Distributed Storage – Restoring highly degraded natural meadow systems to improve local aquifer recharge, water retention, reconnect historic floodplains, and support productive meadows and riparian ecosystems

- Regenerative Agriculture – Promoting voluntary farming and ranching principles and practices that enrich soils, enhance biodiversity, restore watershed health, and improve overall ecosystem function and community health

- Upgrading Agricultural Infrastructure & Operations – Upgrading diversion, delivery and on-farm infrastructure and operations, including irrigation systems

- Cropping Alternatives & New Market Pathways – Developing on-farm operational shifts and market and supply chain interventions to incentivize water conservation, e.g. shifting to lower water-use crops

- Urban Conservation & Re-Use – Incentivizing conservation technologies, indoor and outdoor conservation programs, and direct and indirect potable reuse

- Industrial Conservation & Re-Use – Incentivizing modifications and upgrades to reduce water use and increase energy efficiencies

- Coal Plant Retirement Water – Purchasing or reallocating water rights from closed or retiring coal plants to be used for system or environmental benefits, or other uses

- Reducing Dust on Snow – Improving land management practices to reduce the dust on snow effect — which controls the pace of spring snowmelt that feeds the headwaters of the Colorado River.

- Covering Reservoirs & Canals – Implementing solutions to reduce evaporation from reservoirs and conveyance systems

The full report outlines, in detail, not just the near-term next steps for moving these strategies forward but includes demonstration projects, investments and action-oriented research.

But it’s important to emphasize that these strategies can’t be implemented in a silo. “I” doesn’t work in these conditions. We all rely on rivers, and water, and their continued existence. Our ability to count on them well into the future will be dependent upon our willingness to develop cross-sector partnerships and basin-wide funding for these investments that can be cohesively implemented at a scale commensurate to the challenge. Local, state, and tribal governments must be on board. Our private land partners need voluntary measures and incentives, not mandates.

And we can’t wait for calls on the river, fallowed fields, and dry stretches to act. These investments in climate resilience for the Colorado River are needed now.

Calling all river-lovers and map enthusiasts! A new web project called River Runner, created by data analyst Sam Learner, allows you to follow the path of a raindrop anywhere in the contiguous United States. Using data from the United States Geological Survey, Learner mapped the flow of water throughout all 48 adjoining states. Just click on any spot on the map to create your raindrop and watch it flow downstream.

We are excited about this tool because it provides you with a bird’s eye view of the river and its surroundings. Landmarks such as lakes and major mountains are marked, and the degree of detail and vertical distance from the river is flexible, which means you control the detail. Depending on where you begin your journey, you can start on an unnamed stream or a small river, or you might jump right on to the path of a major river.

Here are some trips we suggest trying out:

Follow the Colorado River

As you trace the path of the Colorado, you’ll notice many of the country’s famous natural wonders. The River Runner website shows the river’s nearby topography, and you’ll see it flow alongside mountains, mesas, and canyon walls. Look down on the river flowing through the Grand Canyon or farther north, and you’ll see it flow through other National Parks, including Rocky Mountain and Canyonlands.

As you watch its course, keep in mind that even a grand river has its limits. Demand for the Colorado River’s water is exceeding its supply. Seven different states rely on water from the Colorado, but its usage is unsustainable. While watching it flow virtually, consider how essential it is that we take measures to ensure it does not dry up.

Follow the Snake River

Using River Runner you’ll encounter the Snake River, a tributary of the Columbia River, predominantly in Idaho, but also in Wyoming, Oregon, and Washington.

Along the Snake River, you’ll notice several dams. These include the Little Goose and Ice Harbor Dams. While the river continues to flow through them, unfortunately migratory fish face each of the dams as a barrier, preventing them from moving freely to their natural spawning grounds. A high proportion of juvenile salmon are killed in their attempts to swim downstream. As you follow the Snake River’s path, consider the benefits of making this a truly free-flowing river.

Follow the Mississippi River

You can start your path on the lengthy Mississippi from an incredible number of places, as it flows through ten states and drains 41 percent of the continental U.S. In fact, if you’re in the mood to explore, you’ll notice that to follow the Mississippi’s route downstream, you don’t need to start all that close to the river itself. Waterways as far away as Montana and Pennsylvania will ultimately drain into the Gulf of Mexico via the Mississippi.

While watching the Mississippi’s path, think about the changes the river has undergone over its history. Throughout the 1900s, wetlands and other floodplain ecosystems were drained and cut off from the river. This immensely degraded the habitat of native species and made flooding far more dangerous. Restoring the river’s natural floodplains is crucial moving forward.

These are just a few examples of the literally thousands of possible water sources you can start with. What the website makes abundantly clear is the extent to which our waterways are linked, demonstrating that the problems facing one body of water will seldom remain exclusive to it. This impact was intentional.

Learner explained, “What I really hope people take away from the tool, besides a fun visual experience, is just how interconnected our waterways are, and the implications of that in terms of pollutants, agriculture, or water use.”

We encourage you to try out the tool, and whether you want to see where the water in your own backyard goes, want to trace the banks of mighty rivers, or even seek to develop conservation strategies, we know you will learn something about how water runs through the country.

This blog was written by Ted Illston and Brian Graber.

The impacts of climate change — felt first and hardest on rivers and water resources in the form of floods and droughts — threaten fragile ecosystems, public health and safety, cultural heritage, our economy and our future. It’s why restoring healthy, free-flowing rivers must be a top priority for Congress and the Biden administration. It’s also why we must chart a smart course for hydropower: a source of energy that may be low-emission but often comes with a high price for river health.

Today, our efforts to ensure a future of healthy rivers and climate resilience took a major step forward.

Representative Annie Kuster (NH-02) introduced legislation that advances the environmental, safety, and economic benefits of healthy rivers and charts a course for hydropower in our nation’s future. The bill, which provides $24.8 billion in spending over 5 years, is designed to accelerate the rehabilitation, retrofit, or removal of the nation’s more than 90,000 dams. Rep. Kuster was joined by Representatives Don Young (AK-AL), Kim Schrier M.D. (WA-08), Julia Brownley (CA-26), Jared Huffman (CA-02), Debbie Dingell (MI-12), Emanuel Cleaver (MO-05), Nanette Diaz Barragán (CA-44), and Bonnie Watson Coleman (NJ-12) in introducing this legislation today. Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-CA) will introduce companion legislation in the Senate later this month.

This bill is urgent and timely, as Congress and the Biden administration consider national infrastructure legislation. Dams are a major component of our nation’s infrastructure – and many are outdated and unsafe. The American Society of Civil Engineers gave dams a “D” grade on its report card on America’s infrastructure. The failure of Michigan’s Edenville Dam last year, and the spillway breach at California’s Oroville Dam in 2017, raised the alarm about the safety of dams in the U.S. An element of the legislation is critical investment to protect the public from the ticking time bombs of unsafe dams.

American Rivers played a key role in crafting the legislation, with vital partnership from organizations including the Association of State Dam Safety Officials, American Whitewater, Trout Unlimited, The Nature Conservancy, Hydropower Reform Coalition, Low-Impact Hydropower Institute, National Hydropower Association, and others.

If enacted, the bill – which is not focused on any particular U.S. dam, river or region – would restore more than 10,000 miles of rivers by enhancing their climate resilience through the rehabilitation or removal of hundreds of the nation’s most hazardous dams. The legislation would also secure the nation’s existing hydropower dams by improving their performance, resilience, and safety. Additionally, it would provide a significant investment in existing federal dams to enhance environmental performance and improve dam safety. Collectively, these efforts will support or create approximately 500,000 jobs.

Key elements of the legislation include:

- Increase federal financial assistance to improve dam safety – $9.75 billion total over 5 years.

- Leverage the federal tax code to incentivize investments in dam safety, environmental improvements, grid flexibility and availability, and dam removal – $4.71 billion for a 30% Tax Credit.

- Create a public source of climate resilience and conservation funding for removal of dams that have reached the end of their useful life – $7.5 billion over 5 years. (Because federal hydropower dam removals require individual negotiations and usually Congressional authorization, they are excluded from this bill’s dam removal funding, but all other dams are eligible.)

- Invest in existing federal dams and relevant research programs to accelerate decarbonization, increase renewable power generation, enhance environmental performance, improve dam safety, leverage innovative technologies, and evaluate disposition – $12 billion over 5 years (combination of $11 billion for dam-owning federal agencies and $1 billion for research).

American Rivers and our partners crafted the legislation as a complete package, and it is essential that these pieces remain whole and connected as the bill moves through Congress.

Since 1912, more than 1,700 dams have been removed nationwide, restoring thousands of miles of rivers. The river restoration movement in the U.S. is stronger than ever, yet there is simply not enough funding to advance all of the projects that are needed for public safety and river restoration. With this legislation, we’re poised to supercharge dam removal – taking river restoration to the next level, with a multitude of benefits for communities nationwide. We’re also acknowledging there is a role for hydropower in our energy future, as long as we balance smart hydro with our need for healthy, free-flowing rivers.

It’s also important to note that American Rivers is unwavering in our support and advocacy for a critical river restoration effort that is not included in this legislation – the effort to remove the four dams on the lower Snake River in the Pacific Northwest, to save endangered salmon and orca. American Rivers views the Twenty-First Century Dams Act, and the effort to restore the Snake River – which we named America’s Most Endangered River® of 2021 — as top priorities and both must move forward.

We urge you to contact your elected officials and urge them to support both of these vital river restoration efforts.

Hydropower and salmon in the Pacific Northwest have had a long, if not occasionally rocky, relationship. The argument over the four lower Snake River dams and salmon recovery seems to be the one that’s always still there the next morning.

There are currently 31 federal hydroelectric dam projects in the Columbia River Basin. Together these 31 dams make up the Federal Columbia River Power System (FCRPS). The Bonneville Power Administration, the agency created to market and transmit power generated by the FCRPS, says hydropower generates about half of the Northwest’s energy.

The four federal dams on the lower Snake River in eastern Washington—Ice Harbor, Lower Monumental, Little Goose and Lower Granite—are part of the FCRPS. For decades, Tribes, conservationists, sportsmen and others have argued the lower Snake River dams pose too great a risk for the long-term survival of Snake River salmon and steelhead. Others have argued the dams are too important to consider removal. Numbers vary annually, but on average these four dams supply about 4 percent of the Northwest’s electricity supply (approx. 1000 average megawatts, or aMW).

Any argument that starts with “all dams are bad” isn’t any more defensible than one that starts with “all dams are good.” Federal dams, like any public infrastructure, should be evaluated based on their overall benefit against overall costs over time. Numbers being numbers, there are obviously disparities among Northwesterners between what constitutes value and what constitutes cost. The best we can do in evaluating the lower Snake River dams is to compare cost and value as we see them using the best available information.

Likewise, any argument that says “replacing the 1000aMW from the lower Snake River dams is no big deal” isn’t a serious one. The argument that says “we can do it, affordably, with clean and renewable electricity we have now,” however, is. In the last 20 years, more than 2,500 aMW from wind, solar, geothermal and biomass has come online in the Northwest, with another 1,500 aMW under construction. A 2018 study shows that a balanced portfolio of clean, renewable energy can place the power produced at the four dams without a loss in the system’s reliability. What’s more, ever-increasing energy efficiencies and conservation are reducing demand significantly. Different analyses have the cost of replacing the electricity production of the lower Snake dams with clean renewables would cost ratepayers on average about an additional dollar a month. Many argue that such an approach is an opportunity to modernize the grid in the Pacific Northwest and create new jobs and growing tax bases across the region.

Operational costs at the four lower Snake dams, built between 1955 and 1975, are hard to estimate. The US Army Corps of Engineers, which operates the dams, announced a $58 million project in 2016 to upgrade two of the six turbines at Ice Harbor, acknowledging that the dam’s 1961-vintage turbines are about worn out. These are aging dams and like any other infrastructure, are not expected to last forever. They are at the point where they need significant investments to maintain them. Over the past 30 years the federal government and Northwest ratepayers have made massive investments in salmon recovery in the Columbia-Snake Basin totaling more than $17 billion, and the costs of ongoing efforts to get and keep operations at the aging dams in compliance with statutes like the Clean Water Act and Endangered Species Act continue to rise.

At American Rivers, we believe that any plan to remove the four lower Snake River dams must include an equitable and robust economic transition plan for affected communities. A key component of our regional dialogue must include the feasibility of replacing the dams’ services with alternative methods of transportation, energy, and water delivery.

Studies show that power from the lower Snake dams can be replaced by new renewable resources like wind and solar with little or no increase in rates or greenhouse gas emissions. Given green energy mandates in the region and the early retirement of coal plants, developing an energy transition plan that supports reliable and low cost energy and that is also equitable is needed. Developing wind and solar replacements for the dams on the lower Snake River will provide jobs, as well as increased reliability and flexibility for the Pacific Northwest energy system.

Inland Northwest farmers feed our nation — and the world. Generations of families have dry land farmed the rolling hills of the Palouse, and Washington continues to be one of the nation’s leading wheat-exporting states. Dry land winter wheat was a natural fit for the semi-arid climate and soils of the Palouse. By the 1930s, Inland Northwest wheat was big business, with ready markets in Asia, but suffered a competitive disadvantage having to move its crop overland to ports in Seattle and Portland by rail. Other wheat-producing regions could move more volume cheaply by barge. The mighty lower Snake and Columbia rivers right there in the front yard were still untamed—too treacherous yet for barge traffic.

Between 1938 and 1975, river transportation arrived. A series of eight federal hydroelectric dams equipped with navigational locks—four on the mainstem Columbia and four on the lower Snake—created a 465-mile barging corridor and made Lewiston, Idaho, the furthest inland port on the West Coast of the United States. Millions of tons of Inland Northwest wheat still make the journey to port on barges every year.

America’s bold bet on barging and hydropower on the Columbia and Snake—and the massive commitment to infrastructure and technology it required—changed the Northwest. We know now that along with the benefits came an enormous cost. Already declining salmon and steelhead runs in the Snake and Columbia—once the world’s greatest—nosedived when the four lower Snake dams came online in the 1970s. Northwest tribes lost ancestral homelands and the salmon our treaties agree they can catch, are being wiped out. Entire economies driven or supported by fishing suffered or dried up altogether.

The 20th century was when we tamed mighty rivers for transportation and energy. Our challenge for the 21st century is to repair this system so salmon, wildlife, and recreation on the lower Snake River can coexist with new energy technology and continued farming. This is a region that can tackle big challenges and achieve them.

American Rivers supports major, job creating investments in transportation infrastructure, technology and efficiency that make moving soft white wheat and other crops and commodities from the Inland Northwest to market better, faster, and more reliable. Crops such as apples, alfalfa, grapes, onions, potatoes, and sugar beets are grown with irrigation water from the reservoir behind Ice Harbor Dam, the lowermost dam on the Snake River near Pacso, WA. Infrastructure upgrades that extend pipes to reach the new river level, add pumps, and deepen wells will allow irrigation to continue along the lower Snake River.

American Rivers envisions a free-flowing lower Snake River, a future of healthy, harvestable wild salmon and steelhead that honors commitments to Native American tribes, renewed fishing economies and vibrant agriculture that helps feed the world.

Salmon and orca are facing extinction as dams block river habitat and climate change heats up Northwest streams. That’s why the Salmon and Orca Summit on July 7 and 8, hosted by the Nez Perce Tribe and the Affiliated Tribes of Northwest Indians, is so timely. The summit, which will take place on the traditional homelands of the Squaxin Island Tribe, represents hope, opportunity, and a chance for real solutions.

The tribes are providing the leadership our region needs right now. Let’s celebrate all that salmon and orca mean to us and seize this moment.

In May, the Affiliated Tribes of Northwest Indians passed a resolution “calling on the President of the United States and the 117th Congress to seize the once-in-a-lifetime congressional opportunity to invest in salmon and river restoration in the Pacific Northwest, charting a stronger, better future for the Northwest, and bringing long-ignored tribal justice to our peoples and homelands. The fate of our Tribes and the Northwest salmon are intertwined.”

American Rivers stands with these 57 tribes in their call to action. We named the Lower Snake River America’s Most Endangered River® of 2021 because no river is in more need of bold, urgent action. We need federal investment this year in a plan that includes the removal of the four dams on the lower Snake to restore the free-flowing river that salmon need. The plan must include infrastructure investments to replace the dams’ services. A well-crafted, comprehensive solution would not only benefit the Northwest, but the nation as a whole by restoring salmon runs, bolstering clean energy and strengthening the economy of one of the most dynamic regions in the country.

We look forward to listening and learning from the native leaders at the summit. It is a historic government-to-government moment in the movement for Indigenous sovereignty and treaty and human rights. Please join us in thanking the leaders participating in the summit. Together, we can save salmon, deliver justice, and invest in the Northwest.

You can watch a live-stream of the summit on the Nez Perce Tribe’s Facebook page.

On June 17, 2021, the American Council of Engineering Companies (ACEC) honored the Patapsco Interceptor Relocation and Bloede Dam Removal, Catonsville, Maryland, at its 2021 Engineering Excellence Awards. This is a national juried competition that evaluates projects from around the world on their excellence in technical savvy, innovation and overall social impact. Projects are rated on the basis of: uniqueness and/or innovative application of new or existing techniques; future value to, and enhancing public awareness/enthusiasm for the engineering profession; social, economic, and sustainable development considerations; complexity; and successful fulfillment of client/owner’s needs, including schedule and budget. Earlier this year, the project was awarded the Grand Prize by the ACEC Maryland Chapter.

American Rivers managed this complex dam removal project in Patapsco Valley State Park on behalf of the dam owner, Maryland Department of Natural Resources. The lead engineering firm was Inter-Fluve, Inc., with support from the firms Hazen & Sawyer (sewer line relocation engineer), Kiewit Corporation (construction firm), and KCI Technologies Inc. (construction management engineer). Removal of Bloede Dam was made possible through a partnership of American Rivers, the Maryland Department of Natural Resources, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Friends of the Patapsco Valley State Park, as well as monitoring partners U.S. Geological Survey, Maryland Biological Stream Survey, Maryland Geological Survey and University of Maryland Baltimore County.

The century-old, 34-foot-high Bloede Dam on Maryland’s Patapsco River was safely demolished starting in September 2018, to restore the river to its natural state. The dam also had become a bane to the region’s health and safety as nine people had died there since the 1980s. The engineering achievement honored with this award highlights the passive release sediment management strategy for removal of 300,000 cubic yards of impounded dam sediment, and the relocation and installation of a new 42-in-diameter sanitary sewer line to replace an outdated cast-iron siphon that ran along the river’s edge.

Removal of this dam is the linchpin of a larger effort to remove four mainstem dams on the Patapsco River aimed at restoring more than 65 miles of spawning habitat for blueback herring, alewife, American shad, hickory shad, and more than 183 miles for American eel, and improve the resiliency of the Patapsco River to a changing climate.

This project was funded with grants from Maryland Department of Natural Resources, Maryland State Highways, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (both through a grant administered by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation as part of the Hurricane Sandy Coastal Resiliency Competitive Grant Program and through the Hurricane Sandy Disaster Relief Appropriations Act of 2013), Coca Cola Foundation and Keurig-Green Mountain.

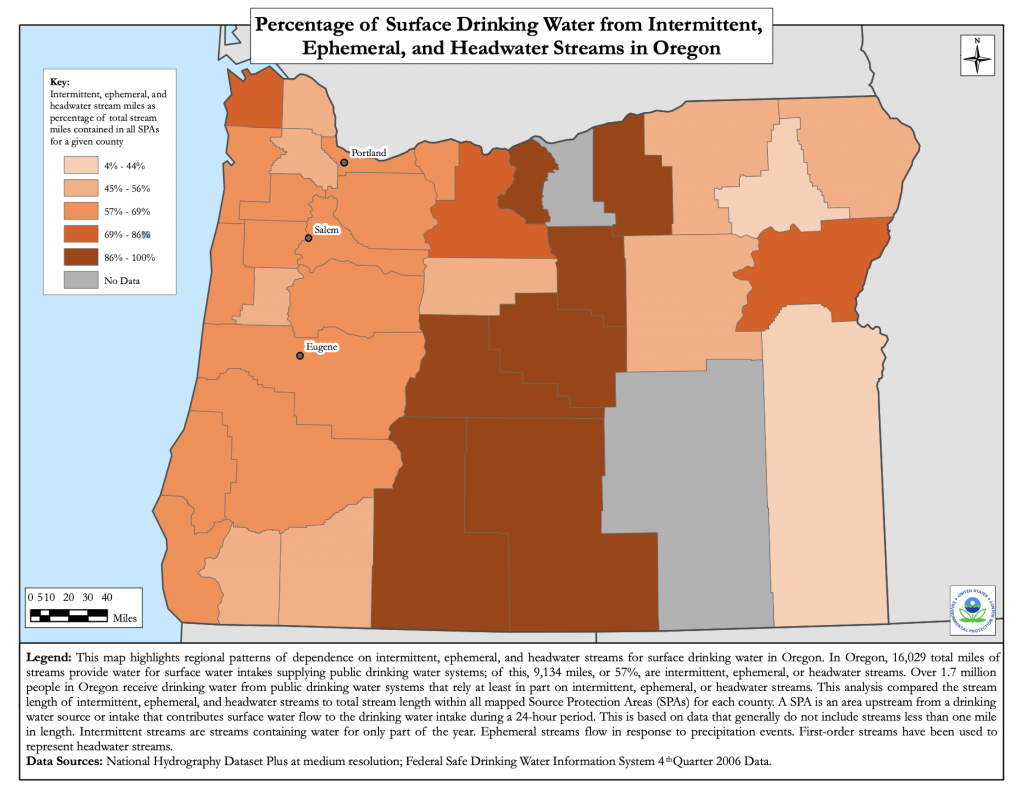

As our collective understanding of the value of healthy watersheds has grown, so too has our appreciation of the critically important role of source water and intermittent streams — those that flow only part of the year — play in providing clean water, habitat and recreation. Across Oregon we have many examples of intermittent and headwater streams that may not flow year round, but provide a myriad of benefits to the larger landscape, watersheds and communities.

If we want to preserve our clean water, recreation, and habitat, it is just as important to protect these streams as it is to protect better known rivers such as the Deschutes, the Owyhee, and the Rogue — in fact, many of these legendary rivers are fed by the vital intermittent headwater streams that come to life each season. These often ephemeral streams give life to the larger rivers and surrounding ecosystems and are increasingly important in the face of climate change. They are the capillaries of the circulatory system of a watershed that allow the river to fan out across the landscape and breathe, delivering life to every corner of Oregon.

More than 1.7 million people in Oregon receive drinking water from public drinking water systems that rely at least in part on intermittent, ephemeral, or headwater streams. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, in Oregon 16,029 total miles of streams provide water for surface water intakes supplying public drinking water systems; of this, 9,134 miles (57 percent) are intermittent, ephemeral, or headwater streams.

For years, we’ve learned the hard way what can happen when we leave these streams unprotected. Hindsight being what it is, we now know it would have been easier to leave a river’s floodplain or wetlands connected to a river to help store floodwaters or recharge aquifers than to reconnect them decades later, for example. We used to remove all of the wood from rivers and streams thinking that the salmon could migrate more easily, but now we know the importance of woody debris in rivers to provide habitat and a shady sanctuary when temperatures rise. Each lesson provides a better understanding of the ways watersheds and rivers work — from top to bottom and side to side — and informs our own work to protect intact functionality before it’s compromised or lost.

Headwaters sort, store and distribute vital nutrients downstream; whole communities of bugs, plants, fish and birds rely on nutrients that originate in headwater streams. They also filter out pollutants, excess silt and maintain water quality throughout a watershed. Even streams that run dry seasonally or intermittently — some 60 percent of all those in the US — are in themselves essential ecosystems that support entire biological communities based on the predictability they’ll run dry during certain times. Headwater streams represent essential migration corridors for spawning salmonids and all manner of wildlife.

Among their many vital roles, headwater streams are the frontline of defense for rivers against climate change. Many serve a dual role as the gatekeepers of vital groundwater — both as collection areas for recharge and as distributors of cold, clean groundwater and snowmelt that help keep temperatures livable for fish and so many others downstream dependent on it, not to mention freshwater for humans to drink and irrigate with. Nowhere is this function more important than in arid desert watersheds.

Headwater streams at upper reaches of watersheds come loaded with lessons about their critical function to the perennial streams and rivers they feed downstream. We’d be wise to protect headwaters now as there may be no do-overs on this one. Without headwaters, by definition, there is no river downstream. Damage or loss of headwater habitats echoes throughout the watershed and beyond.

Fortunately for Oregonians, Senators Wyden and Merkley have introduced the River Democracy Act, aimed at protecting more than 4,600 miles of new Wild and Scenic Rivers in the state, including many intermittent and headwater streams. This bill, informed by listening sessions in urban centers, remote communities and everywhere in between, aims to protect rivers and streams nominated by more than 15,000 Oregonians. The Wild and Scenic Rivers Act is one our nation’s best tools for safeguarding freshwater rivers and streams for future generations, and will ensure our rivers keep functioning as nature intended — including those that show themselves during certain seasons. Whether we can see them or not, these streams are working hard for all of us, and it’s time we get to work for them.

Take action to thank Senators Wyden and Merkley for their leadership: https://ouroregonrivers.org/take-action/.

Learn more about two Headwater and Intermittent streams protected in the River Democracy Act:

- Dry Creek, a tributary of the Owyhee River in southeast Oregon, courses through rarely seen combinations of rock and erosion patterns that have carved its long pools. Dry Creek’s unique geology and has allowed it to retain a genetically unique population of redband trout in an area where most neighboring redband populations have been compromised or lost. Dry Creek also provides outstanding wildlife habitat for sensitive species such as the Columbia spotted frog.

- Rough and Ready Creek is a key tributary of the Illinois River in southwest Oregon. Originating in the Kalmiopsis Wilderness, Rough and Ready meanders down through the South Kalmiopsis Roadless Area in characteristic bends and braids. Its unique geology, natural diversity and gin-clear waters have combined over the ages to form a floodplain environment exceptionally rich in rare plant communities, earning Rough and Ready its reputation as a “botanical wonderland.”

- Basin Creek is a headwater stream in the Joseph Creek watershed an important sub-watershed of the Grand Ronde River. Basin Creek is a cold water source that emerges on lands of the Nez Perce Tribe in Northeast Oregon before flowing through National Forest. They refer to this area as the “Precious Lands” and Basin creek is a prime source of clean water important for salmon and steelhead.

Even as much of Oregon has barely begun the recovery process from last year’s catastrophic wildfires, this year’s fire season has gotten off to an early and ominous start. The Pomina fire in drought-stricken Klamath County — started in mid-April — is yet another sign that wildfires all across the West are starting earlier, burning hotter across larger areas, and burning later into the year than ever before. As of writing this post, according to the Oregon Department of Forestry, 350 individual fires have already sparked across our state.

In a recent Instagram post, Oregon Senator Ron Wyden wrote, “This fire season has the potential to be the most devastating in our nation’s history. The climate crisis is here, and we’re living it.” The threats are so severe that Senator Wyden and fellow Oregon Senator Jeff Merkley have already sent a letter to federal agencies pressing them to “ensure our state has the resources it needs to fight these fires and keep communities safe.”

Thankfully, Oregon’s senators have already been at work crafting legislation to bolster wildland firefighting and resources. In February, Senators Wyden and Merkley introduced federal legislation — the River Democracy Act — that will more than triple Oregon’s Wild and Scenic river miles and in doing so also strengthen wildfire preparedness statewide. On June 23, the U.S. Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources held a hearing on the bill, moving it one step closer to protecting more than 4,600 miles of Wild and Scenic rivers in Oregon.

The River Democracy Act provides for stronger wildfire risk assessment and planning for homes and businesses near Wild and Scenic rivers, greater inter-agency coordination in fighting wildfire including with Native American Tribes, and more federal resources to repair wildfire damage to infrastructure, drinking water quality, and watersheds. The bill also provides $30,000,000 annually for Wild and Scenic Rivers that provide drinking water for downstream communities or those that have been degraded by catastrophic wildfire.

Most of us associate Wild and Scenic River designations with protecting the natural, recreational, cultural and ecological values of these waters — and we should. We should also understand the critical importance of national Wild and Scenic River designations as a tool to help us prepare and protect against an ever-increasing combined threat from catastrophic wildfire, warming climate, drought cycles and more people in harm’s way. Healthy, resilient rivers lead to healthy, resilient communities — and the importance of these life-giving rivers only becomes more vital in the face of climate change and fire seasons like the one we’re looking at this year.

But you don’t have to take my word for it. Over the next several weeks, we’ll be sharing guest posts from people who have been — and still are — on the front lines.

Stay tuned and stay safe.