There are few things at American Rivers we argue over as much as the question: what is the best river song?

Traditionalists prefer the classic takes on “Ol’ Man River” or “Song of the Coulee Dam.” Old (and young) hippies swear by the Grateful Dead’s “Black Muddy River.” Pop-music lovers swim down Billy Joel’s “River of Dreams.” And millennials prefer current offerings, like Dar Williams’ newest, “Today and Everyday.”

Me? I am a neoclassical river-song lover. Led Zeppelin’s cover of “When the Levee Breaks” is a perennial classic. “Pain Lies on the Riverside” and LIVE’s anthemic drumming spoke to me in college. But my current favorite is Joni Mitchell’s iconic “River.” I’m fairly certain Joni didn’t intend that song to be about an actual river, but the rules about what makes a best “river” song are pretty loose, right?

Here are some other current favorites from our staff:

“In African American spiritual music, water (especially rivers) symbolizes safety, rebirth and the challenges we endure. This roots song is one of the latest in that long tradition. For me, it symbolizes the obstacles that we as African Americans face, but also the many moments of joy, love and triumph that are often hidden or ignored by popular media.” – Janae Davis, Associate Director of Conservation, South Carolina

“Proud Mary” — Creedence Clearwater, Ike & Tina Turner

“This song speaks to me with its rolling style and river imagery. Traveling, going with the flow: ‘You don’t have to worry if you got no money. People on the river are happy to give.’ I love road trips, and this song has that sense of adventure, of meeting new people, new towns and an easy-does-it simplicity. I sing along loudly and badly to any version.” – Pat Callahan, Director of Philanthropy, California

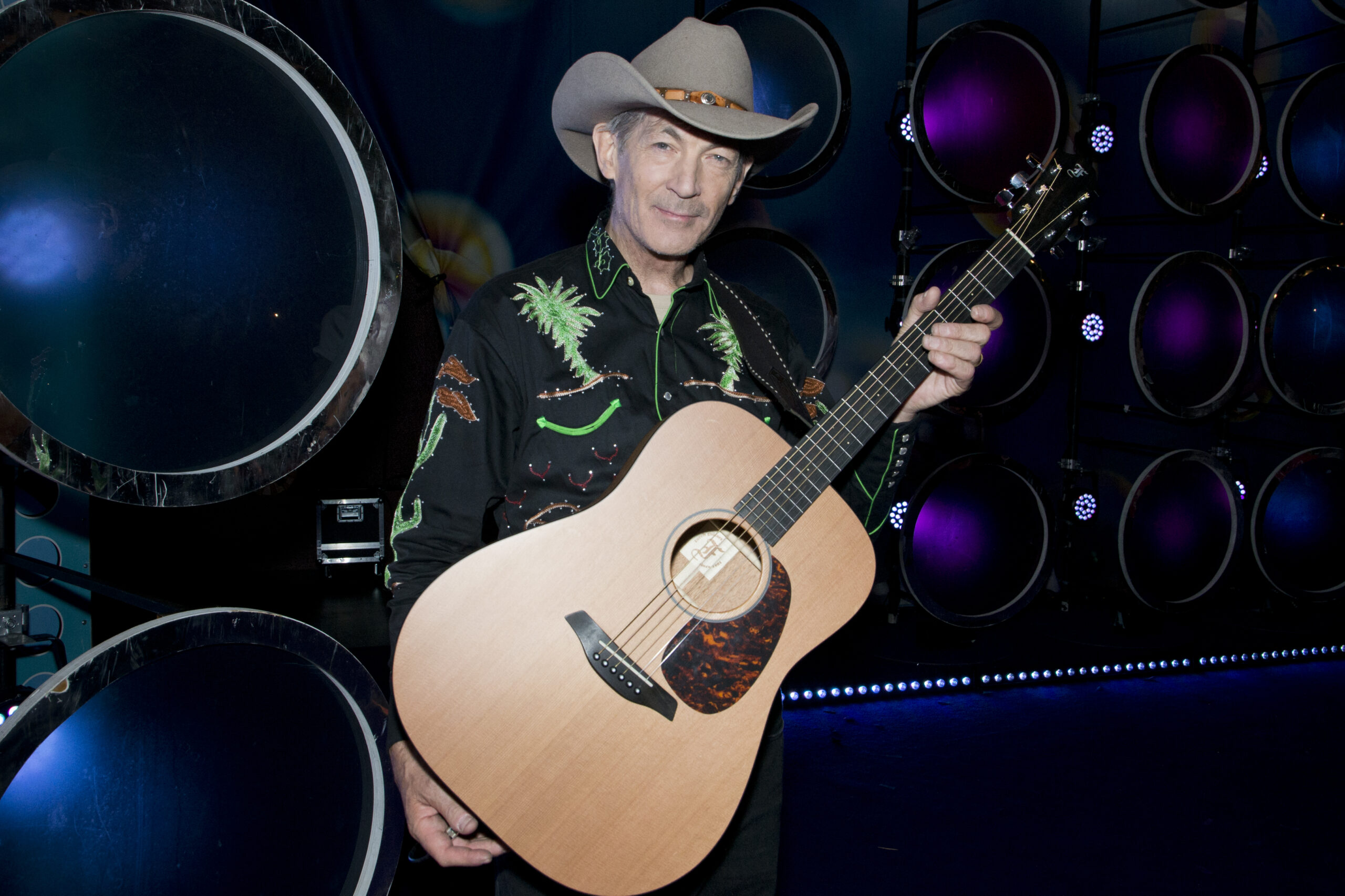

“Going Down to the River” — Doug Seegers

“Growing up, the rivers and creeks outside Austin were my sanctuary. They were my place to explore, grow and simply be a kid. This song reminds me that whatever is going on in your life, you can always go down to the river and be rejuvenated.” – Brandon Parsons, Associate Director of Restoration, Washington

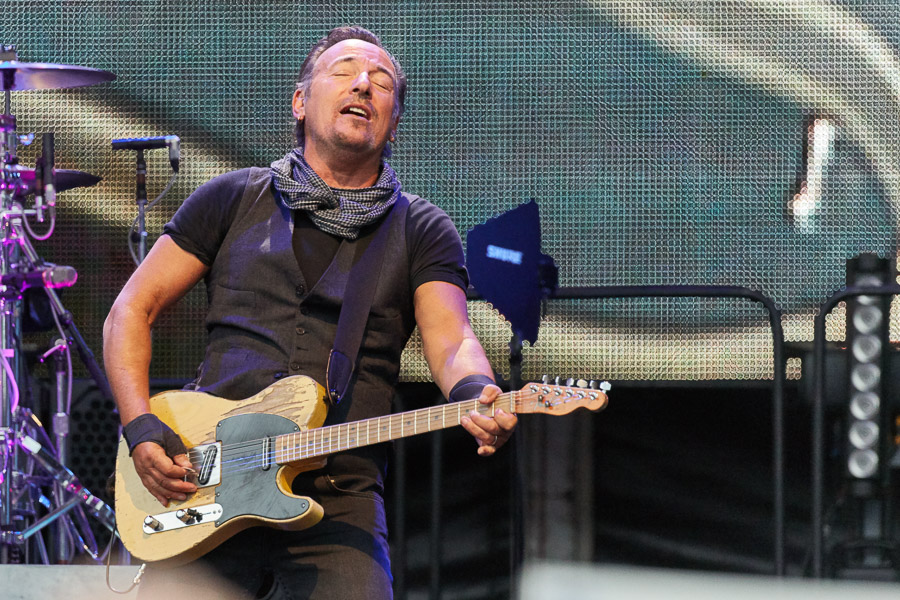

“The River” — Bruce Springsteen

“I can relate to this East Coast, blue-collar, coming-of-age story that is somehow sad, sweet and hopeful all at the same time. It talks about the river as a place where we go for freedom, celebration and respite, in a way that rings true to me and reminds me of what’s most important in life.” – Jen Adkins, Director of Clean Water Supply, Pennsylvania

The great thing about river songs is that the lyrics can be about anything. Yes, some are obviously about a memorable place in the songwriter’s life. Cripple Creek, the Green River, Yellow River, Kern River, Black River, Tennessee River and the James River all come to mind.

But then there are songs that actually have very little to do with rivers at all. We like to lump them onto lists like this for fun. A number of artists have done “Take Me to the River” and “Moon River,” both take on relationship melodrama. “Satan’s River” is either a gospel-country duet from Porter Wagoner and Dolly Parton or a metaphor for the climate change crisis. And then there is Patti Smith’s take on a river song, which is what Willie Nelson must do after being on the “Whiskey River.” (If you don’t get the reference, well….)

What makes a good river song is decided by the listener. We’ve been collecting river songs in a YouTube playlist over the years. Do you have a favorite? Are we missing something? Drop us a comment, or hit us up on social, we’d love to hear what you think are the all-time top river songs.

North American River Otters are cute, fluffy river dwellers, but did you know they are also a crucial indicator of an aquatic ecosystem’s health?

River otters are indicator species so their presence is a sign of good water quality. Freshwater ecosystem health is of particular concern to us humans because of our reliance on clean water. Think about it — most cities are built on rivers, all people need clean water.

Otters exhibit robustness and resilience to climate disruption events like strong storms, drought, sedimentation, and temperature shifts. However, the otter’s food is more sensitive to the impacts of climate change and other ecosystem impacts like pollution. Otters are at the top of the food chain which means impacts to their food can accumulate to impact otter populations. Other climate related threats to river otters and their food include sea-level rise and salt water intrusion into freshwater habitat.

The good news? These furry animals are extremely adaptable and occupy “a broad ecological niche.” This means otters thrive in a wide variety of environments and enjoy a wide variety of food.

North American River Otters, while cute, fluffy little beings that swim on their backs and flitter on river banks, are incredibly important at indicating how detrimental cumulative environmental changes can be. We see these little guys as barometers of their habitats, and ecosystems at large, as our climate changes. As climate change continues to affect freshwater environments, this is a species worth paying close attention to.

“We begin in water and we return to water,” contemplates Juanita Wilson, an enrolled member with the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, whose traditional lands span what are now eight states across the Appalachian Mountains.

She reflects on the Cherokee’s traditional relationship with rivers: “The Cherokees have always viewed the river as ‘Long Man (Gunahita Asgaya),’ whose head lay in the mountains and the feet in the sea. Long Man (or Long Person), was a revered figure among the Cherokee as one who provided water to drink, cleanliness, food, and numerous cultural rituals tied to medicine and washing away bad thoughts and sadness.”

American Rivers honors this relationship the Cherokee have with rivers, and we honor the deep, diverse connections that other Indigenous Peoples have with rivers and water. Across the country, tribes are caring for the land and are powerful leaders advocating for clean water and healthy, free-flowing rivers. Many are leading successful efforts to revive traditional knowledge in their communities and apply their skills and wisdom to protect and restore rivers especially in this era of climate change.

On Oregon and California’s Klamath River, for example, the Karuk, Yurok, Klamath and other tribes have led the effort to remove four dams to bring back salmon runs and improve water quality, with dam demolition scheduled to begin in 2023. In the Northwest, the Nez Perce Tribe, Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, Yakama Nation, Upper Snake River Tribes, and others are leading the effort to restore a free-flowing lower Snake River, in what would be the biggest river and salmon restoration effort in history. The Navajo and Hopi have fought to protect the Grand Canyon from harmful development. And the United Tribes of Bristol Bay were instrumental in killing the notorious Pebble Mine proposal that would have devastated the world’s biggest salmon runs.

It is important to also acknowledge that deep injustices persist toward Indigenous People. Tribes were forced out of their homelands and away from their sacred rivers and traditional food sources and continue to this day to disproportionately feel the impacts of dams, pollution, and inequitable water management decisions. Climate change, which is bringing increasingly severe floods and droughts, is exacerbating these current problems. For too long, Indigenous People have been kept out of decision-making and marginalized by the mainstream environmental movement.

We have a responsibility to do better. If we are to heal our relationship with rivers, if we are to confront the climate crisis and adapt to its on-going impacts, the traditional ecological knowledge and perspective held by Indigenous People is essential. Ensuring tribes play a leadership role in forging river conservation solutions is vital to the future of the environmental and river movement, and our nation as a whole.

On Indigenous Peoples Day, I ask you to join me in the small step of committing to learn more about the ancestral lands where you live and work (https://native-land.ca/ is one resource), and to support Indigenous-led river conservation efforts in your area.

On October 20 in western North Carolina, Juanita Wilson is inaugurating a river cleanup. She says her goal is to “live our connection with Long Man by cleaning trash out of waterways. However, this is much more than a one-time ‘river cleanup,’ it is a cultural awakening and/or re-awakening. Honoring Long Man Day cleanups will continue into the future.”

Today and every day, it is leaders like Juanita who are providing the vision and determination that our rivers and communities need to thrive.

Clear, spring-fed creeks trickling from the steep slopes of the Appalachian Mountains join into powerful rivers, then widen and flow into the sea. Long Man is a personification of the river, whose head lays in the mountains and feet stretch to the sea.

The rivers of the Appalachian region are some of the country’s most biodiverse ecosystems and have long been important to the traditional inhabitants of these lands, including the Cherokee.

“Long Man (Ga-nv-hi-dv A-s-ga-ya) is a revered figure among the Cherokee,” observes Juanita Wilson, a tribal member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians in North Carolina and head of the tribe’s Talent and Development Program. “Long Man provides water to drink, cleanliness, food, and numerous cultural rituals tied to medicine and the washing away of bad thoughts and sadness.”

This is why Juanita is inaugurating the first Honoring Long Man Day, on October 20, 2021, in Cherokee, North Carolina.

Juanita believes that if tribal youth learn about and reconnect with Long Man, they will also recognize that rivers provide for us every day — and that taking care of rivers is the right thing to do.

“On this day, we will live our connection with Long Man by cleaning trash out of our waterways. However, this is much more than a one-time ‘river cleanup.’ It is a cultural awakening and/or re-awakening. Honoring Long Man Day cleanups will continue into the future.”

The Honoring Long Man Day river cleanup will take place on the rivers around Cherokee — the Oconaluftee and Tuckasegee rivers and streams in the area. Honoring Long Man Day participants will gather in the morning to learn about Long Man and share breakfast.

Juanita hopes that this is just the beginning. She would like to see Honoring Long Man Day become an annual, regionwide event that inspires a new generation of people devoted to river stewardship.

Click here to register for the Honoring Long Man river clean up on October 20. We encourage EVERYONE to take some time on this day to clean up a waterway near you. Post a picture using #honoringlongman.

Those of us who care deeply about rivers have much to learn from the Indigenous People who are using their sovereignty, knowledge, and expertise to work for a future in which local communities and river ecosystems can thrive.

Together, listening to the wisdom of others, we can begin to give back to the rivers in our lives — and honor all that rivers give to us.

This is a guest blog by Boulder, CO based photographer Tim Romano. All images were taken by him. All rights reserved.

For decades, I have been exploring and photographing the Upper Colorado River and its tributaries. Not for any reason other than I love the watersheds associated with it, have grown up on them, and truly feel connected to these trickles of water. I literally can’t help it. As a photographer and river rat it’s always been something I’ve done. For fun…

Yet something this spring changed for me in that regard. After the COVID daze of the last year and surreal summer of fires the Upper Colorado endured last year, I felt compelled to actually go out and document what was happening, essentially in my home space.

It’s hard to put into words, but after a spring of running river miles by floating the San Juan, main stem of the Salmon, Gunnison, Arkansas, Roaring Fork, multiple small tributaries on the Front Range, and the Colorado I realized I was actually chasing something. Something deeper than simply the next great shot, or the next slick run through roiling whitewater, I literally was chasing the future of my home, and the home of my little girls.

For the first time in my life, I felt like I was doing it for something beyond just thrills. A certain truth set in for me this year as my home river was reduced to a mere trickle, smoke filled the air every day for a second or even third summer in a row, fires started, and water temperatures approached the mid-seventies. This is how it’s going to be. Maybe for the rest of my adult life and my kid’s as well? That’s not to say things can’t be done to reverse some of the damage, but throughout this summer I’ve felt like I must see and do as much as I reasonably could with the river. If I was invited on a permit, I said yes. If I could squeak in an extra lap on the St. Vrain after work, I did. If I had to drive four hours to fish a bit of river I’d never seen, I went.

In early July, a commercial photoshoot of mine was canceled due to smoke. I had already booked the time (a few days,) rented some gear, and had my camping stuff packed. I was frustrated, mad, and sad all at the same time. Instead of just moping and being angry, I decided that it would be cathartic for me to go see some of the fire damage from last year and experience what was really happening on some of the drainages that feed the Colorado. My need to document what’s going on was strong. So I went. It wasn’t necessarily uplifting, and the reality of the situation certainly hurt. But I had to share. Maybe you’ll find it depressing, educational, or somehow perhaps it will inspire you to take note of what’s going on, and maybe find something within you that you can do – for the river.

The extent of the devastation from the East Troublesome fire that ripped through much of the Colorado headwaters is like no fire scars I’ve ever seen. In one day the fire burned 120,000 acres and in total destroyed 193,812 making it the second largest in Colorado history. This image was taken just west of the Kawuneeche Valley in Rocky Mountain National Park.

Smoke has filled the air almost every day this Summer and sadly has become so normal that it just seems like a part of life now on the eastern edge of the Rocky Mountains. This image is from the top of Independence pass next to one of the nearly dried up feeder streams to the Roaring Fork river – a tributary of the Colorado.

The inflow at Highland Marina is basically non-existent as plants start to take hold on what was once the bottom of Lake Granby. One can almost walk from one side of the bay to the other without getting wet. The lake is the third largest body of water in Colorado and is a major storage reservoir for the Colorado river.

A backhoe pushes the dock store further out into what’s left of Lake Granby and backfills with dirt to make sure people can access it from the water. The background shows damage to the trees from the East Troublesome Fire which basically burned a good portion of the West side of the lake.

Thick smoke fills the air over the dewatered Roaring Fork River near Glenwood Springs while swallows take to the air consuming grasshoppers that are emerging months earlier than normal this year.

The “mighty” Colorado next to I-70 in Glenwood Springs is deeply discolored from fire-caused mudslides in Glenwood Canyon. There’s real concern that these heavy loads of sediment will not be easily washed away as lingering low flows year after year persist, smothering bug life and coating the bottom of the river with thick muck.

A lone trailer sits empty near the nearly dewatered confluence of the North Fork of the Gunnison and and main Gunnison Rivers earlier this summer. The North Fork’s flows were about 10 CFS (Cubic Feet per Second) and temperatures were approaching 80 degrees. Driving into the Gunnison River valley makes you realize that green wouldn’t even be a color on this thin ribbon of land if it wasn’t for this important artery of the Colorado.

Raft guides and clients walk a boat out of the sediment laden waters of the Colorado at the Grizzly Creek Rest Area in Glenwood Canyon on the Colorado, where a 36,631-acre fire that burned almost the entire canyon occurred, burning from August 10th until December 18th, 2020.

A lone raft launches from the Shoshone put-in on the Colorado. Since this image was taken several, 100 & 500 year rain events have coursed through the burn scars, completely covering both the highway and across the entire river, altering rapids and pumping thousands of cubic feet of mud and debris into the river.

A soiled and sad Colorado River below the dam that holds water for the Shoshone power generating station. Shoshone holds senior water rights to more than 1,250 CFS, pulling water from the headwaters of the Colorado westward, but sometimes dewatering this short stretch in Glenwood Canyon.

A quick stop on a misty evening on the top of Independence Pass en-route to a float can sometimes trick you into thinking all is fine down valley with low clouds, moisture and rain cascading down to the river.

Water clarity in the headwaters of the Colorado River seem to be more this color than anything else, after the fires of last year and monsoonal rain events that have followed this summer.

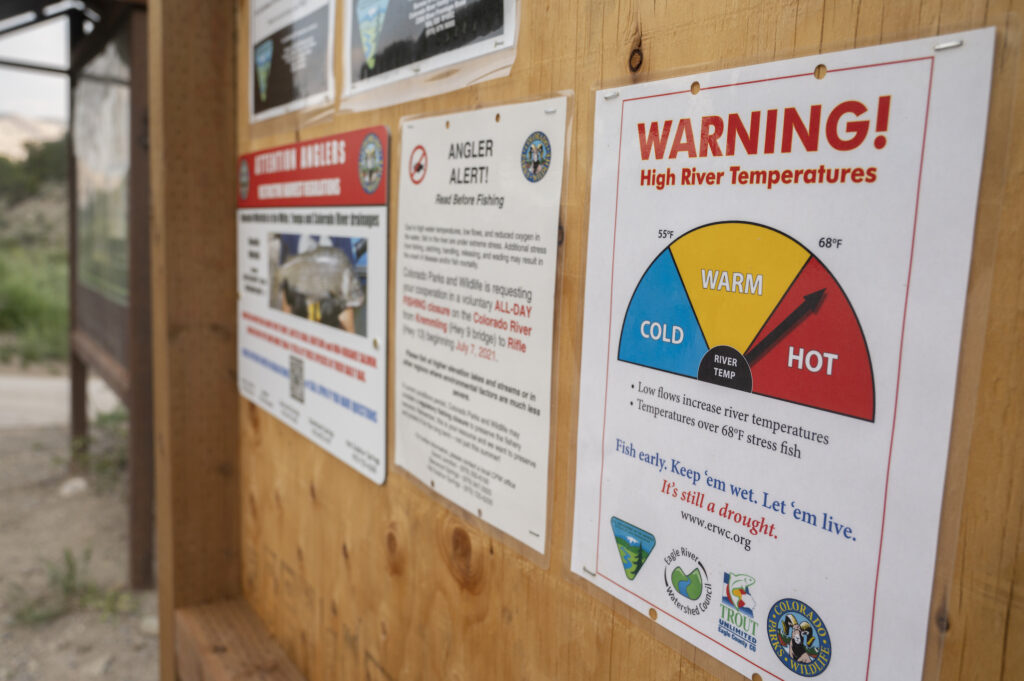

These signs were posted in early June on the upper Colorado. On June 14th, A gauge far upstream of these read 73.76 degrees and a mere 335 CFS of water. During what should have been a raging runoff on the Colorado river.

Riverbanks have looked like this a lot the past few years and I suspect we’re going to have to get used to seeing a lot more of them going forward.

Whitewater enthusiasts may also have to get used to changing landscapes like this one in Glenwood Canyon. Not only is a burnt forest an eyesore, it holds serious complications for the watersheds, infrastructure, and outdoor recreational enjoyment that they once anchored.

It’s never a good sign when plants are growing on mid-stream sandbars in early July. The Upper Colorado River just upstream of Lyons Gulch, one day after a water call bringing the water up from what was about 400 CFS, making what would have been a frightening trickle look almost normal.

Newly installed and updated boat ramps covered in sediment and in some spots becoming almost unusable due to the ongoing low water situation.

A muddy and critically low Colorado river above the Horse Creek Launch shows the disparity of who has water, how it’s used, wasted, and what the land would look like if the water disappeared.

After enduring one of the longest and most severe droughts in recorded history – a length that legitimately amounts to a good portion of my adult life here in the West, I’ve come to realize this isn’t going away. We can do our snow dances, pray for rain and use our magical thinking skills to try and fix it, but the reality is it’s going to get worse. The science says so, and as an observer of the outdoor world I can feel it and see it happening year after year.

It may ebb and flow. We might have some big water years coming up, but more than likely we’re going to be dealing with lots of low water, fires, dewatered reservoirs, and rivers that we once knew – changed for good. As water lovers we all either better be really good at not caring, do what we can now to save what’s left by conserving, or straight up adapt to what’s left. The new reality is here now, and sadly it’s not likely to get a whole lot better soon. Unless we all lean in, and act.

This is a guest blog by Emma Schmit and Adam Mason. Emma works for Food and Water Watch, an organization fighting for safe food, clean water, and a livable climate for all of us. Adam works for Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement, an organization creating change in Iowa through grassroots organizing, educating, and mobilizing on issues that impact communities the most.

Iowa’s water crisis is being exacerbated by the climate crisis — turning an already concerning situation into one of serious peril. As drought and extreme heat shake our country, Iowa’s government has consistently sided with profit over the people when it comes to the fate of our critical rivers. The Raccoon River, which runs from northwest Iowa down to Des Moines in central Iowa, was named one of America’s Most Endangered Rivers® of 2021 due to the unmitigated pollution from factory farms within the Raccoon River watershed. Iowa in general, and the Raccoon River in particular, are facing a water crisis of epic proportions. While this crisis is largely caused by factory farms and industrial agriculture, the impacts of climate change are only exacerbating this already critical situation.

As climate-change fueled drought impacts the river, concentrating pollutants and encouraging the growth of toxic blue-green algae, the half a million Iowans who depend on the Raccoon River for drinking water face mounting concerns. In June, residents of Des Moines were asked to cut back on watering their lawns in an effort to reduce water consumption. As ongoing drought intensifies water shortages in the region, residents were warned that a failure to reduce consumption might impact their drinking water supply.

This year’s water rationing is only the latest in a string of drinking water challenges facing Des Moines residents. Just last year, under similar drought conditions, Des Moines Water Works had to resort to using water from storage wells and an emergency reservoir as the city’s primary drinking water supply for several weeks because the primary supplies, the Raccoon River and Des Moines River, were rendered unusable due to out-of-control blue-green algae blooms and low flows.

Twenty years ago, in 1991, Des Moines Water Works was forced to build one of the world’s largest — and most expensive — nitrate removal systems. This was necessary to treat the unsafe levels of nitrates entering the Raccoon River from factory farms and industrial agriculture fertilizer use upstream. Less than two decades later, the system was overwhelmed by the ever-increasing levels of nitrates flowing into the river from the proliferating factory farm operations in the watershed. As a result, in 2017, Des Moines Water Works had to expand this nitrate removal system. Ratepayers — not the polluting agribusinesses upstream — have borne these costs. Despite these alarming trends and the threat they post to public health, the state of Iowa continues to forgo meaningful action to address this water crisis. Instead, elected officials cozy up with the very industries that pollute our water: massive corporate agribusinesses.

This failure to put the needs of Iowans before the greed of a multi-billion-dollar industry only serves to heighten the threat facing the Raccoon River and hundreds of thousands of Iowans. In an effort to force the state of Iowa to address this crisis, Food & Water Watch and Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement filed a lawsuit against the state in 2019. Citing the Public Trust Doctrine, the lawsuit alleges that the state has failed to meet obligations requiring the protection of the Raccoon River for the use and enjoyment of all Iowans. We argued that Iowa’s failure to abide by the Public Trust Doctrine has allowed agriculture interests to desecrate and pollute one of the state’s most important waterways.

The lawsuit was intended to force the state into putting forth actionable, mandatory water quality solutions designed for widely shared prosperity and stewardship of our natural world. The Raccoon River watershed is saturated with more than 750 factory farms, requiring billions of gallons of untreated manure to be disposed of on our land and in our water. There are very few regulations and even fewer enforcements for the factory farm industry in Iowa. While the state has adopted a Nutrient Reduction Strategy to decrease water pollution from agricultural sources, engagement is entirely voluntary. In order to see real, meaningful water quality improvements, the lawsuit sought a moratorium on the construction of new and expanding factory farms within the watershed, as well as the adoption of a mandatory remedial plan to restore and protect the Raccoon River.

In December 2020, this lawsuit went before the Iowa Supreme Court. The state had filed an interlocutory appeal claiming that it was the responsibility of the legislature, not the court, to address Iowa’s water crisis. Citing the legislature’s repeated failure to take meaningful action to curb Iowa’s water crisis, we of course disagreed.

In June 2021, the justices issued their decision in our case. In a divided 4-3 ruling, the majority declared that it is not the Court’s responsibility to hold the state accountable to the public, and they chose to dismiss our case.

Despite the Court’s decision to dismiss the case, we know Iowans have a right to clean water and we know that’s a right worth fighting for. We remain committed to exhausting all options for Iowa’s people, communities, and environment that we have fought so hard to protect through this lawsuit. On July 1, we chose to file a petition for reconsideration with the Iowa Supreme Court requesting that the justices re-examine the ruling. While it is uncommon for such petitions to be granted, in a Court decision as divided as this, we believe we have an obligation to our members and the people of Iowa to leverage every available option to fight for our right to clean water.

Regardless of the court’s decision, we know that this fight has never lived only in the courtroom. We will continue building power behind the movement for clean water in Iowa, and we’ll continue to use every path available to secure the future we deserve. The people of Iowa deserve thriving rural communities, clean rivers, streams and drinking water, and a bright future — and this future is incompatible with unsustainable, polluting industrial agriculture. Corporate agriculture may dominate our state right now, but this movement grows every day, and the power of everyday people coming together will overcome the industry’s stronghold on our elected officials and our state. Iowans deserve better and we are demanding better. We will not allow our water to be sacrificed for corporate gain.

This is a guest blog highlighting some of America’s Best River Towns by American RiversSM — written by Katrina Cubanski and Ciara Regan, two amazing interns who worked with the Communications team this summer.

This summer, we asked our supporters to share their favorite river towns. And we were thrilled with the enthusiastic response! We asked you to consider factors including conservation actions, clean water and river health, access, recreation, culture and history. And you spoke up passionately – thank you for sharing your stories.

We can’t include every great river town here (we see you, Milwaukee, New Orleans, Sacramento and Minneapolis!), but here are some of your most popular picks for America’s Best River Towns:

Cleveland, OH

Anyone concerned with issues of clean water or water conservation knows that in 1969 the Cuyahoga River, which runs through Cleveland, caught fire, contributing to the birth of the environmental movement. Since then, the river has seen tremendous recovery and American Rivers named the Cuyahoga “River of the Year” in 2019.

In addition to this legacy of conservation, the Cuyahoga River offers recreation such as paddle boarding, kayaking, and canoeing.

You said:

“The Cuyahoga is the ultimate success story for environmental revitalization!”

“It’s so cool to see a giant lake freighter one minute and paddle boarders or a rowing club go by a few minutes later!”

“Cleveland’s Cuyahoga River has risen like a phoenix since the 1969 fire.”

“The Cuyahoga River is an object lesson in how the combined forces of city, state, and federal resources can turn around the once bleak prospects of a river into a thriving multi-use resource.”

Steamboat Springs, CO

Steamboat Springs, on the Yampa River, boasts a strong community of river lovers, including our partners at Friends of the Yampa. They hold an annual river festival to emphasize the importance of respecting the river while appreciating all that it has to offer. Friends of the Yampa is and has been part of other local conservation efforts, like youth education and awareness initiatives and fundraising, as well. The community feels a strong connection to the river, seeking to protect both the local ecosystem and the opportunities for recreation it provides.

You said:

“These organizations have gotten the support of the agricultural and tourism industries to protect and enjoy the river.”

“It’s so nice to be able to paddle fun whitewater through town.”

Colorado was a popular state for Best River Towns. Other responses highlighted community conservation and/or river recreation in Durango on the Animas River; Buena Vista and Salida, both on the Arkansas River; and Glenwood Springs on the Colorado and Roaring Fork Rivers.

The Forks, ME

The Forks has quite the fan club. We received upwards of 30 responses raving about this town on the Kennebec and Dead Rivers. The area offers great outdoor recreation and a welcoming community. Every year the community puts on an event called “Guide Olympics,” where river guides compete in several athletic events, bringing together the community and raising money for a particular cause.

We checked in with Pete Didisheim, Advocacy Director with Natural Resources Council of Maine. He confirmed, “The Forks is a great little town. Fantastic whitewater rafting through the Kennebec Gorge. A spectacular drive to the area on Route 201, especially with fall colors. Take a hike to Moxie Falls, go fly fishing, or look for a Moose – this is a wonderful area of Maine, with water at its heart.”

Local conservation groups are working further downriver to restore a free-flowing Kennebec in order to save endangered Atlantic salmon and other sea-run fish.

You said:

“Whether you are an adrenaline junkie or a 4-year-old toddler that loves looking for fossils this community is welcoming, exciting, and pure magic”

“Having been a part of this happy place for almost 40 years, and having rafted all over the world, I can safely say river people and the incredible culture they inhabit are the best examples of human cooperation to be found on this planet.”

“The Forks is like no place else. Going to The Forks is like going home.”

Richmond, VA

Richmond, Virginia on the James River is hailed for its amazing urban whitewater, with class III and IV rapids. The river offers outdoor recreation for people of all ages and experience in the forms of more mild rafting, swimming, and walks along the river.

Fun fact: in 2012, Richmond was a winner of Outside’s Best River Towns in America contest, conducted via a partnership with American Rivers.

Community members hold great fondness for the river, and groups organize for its maintenance and conservation. For instance, The Conservation Fund has recently purchased land along the James for the purpose of river conservation and protecting the area from development. This move, part of a partnership with Capital Region Land Conservancy, James River Association, and the City of Richmond, will also add new public river access and bolster youth education programs.

You said:

“I grew up a mile from this historic river & it will always be a part of my life.”

“The falls of the James River at Richmond offer the best urban whitewater on the planet.”

“Community members have made tremendous progress towards making the James a clean, safe, and accessible river for everyone to enjoy.”

Pittsburgh, PA

Three rivers: the Allegheny, Monongahela, and Ohio, come together as they pass through Pittsburgh. Because of this connection, Pittsburgh is the perfect place for gentle strolls with open expanses of river views. The city also hosts the Three Rivers Arts Festival annually, celebrating the culture and history of Pittsburgh. The festival grants the opportunity to browse art while appreciating the city’s scenery.

You said:

“I have been all over the world and always came home to Pittsburgh to live and to work. Many people have boats and spend their free time on the rivers.”

“These rivers are the Allegheny, Monongahela and Ohio. Each river brings its own hometowns favor and history. Once a year for seven to ten days there is a Three Rivers Festival to celebrate all that is Pittsburgh history, culture and future promises.”

Macon, GA

Located on the banks of the Ocmulgee River, one of the most fascinating parts of Macon is the Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park. Here you can learn about thousands of years of human life in the area, and the important role that the Ocmulgee River has played in history. The park and the river serve as wonderful learning opportunities for residents and visitors alike. As a bonus, the area is also home to beautiful walking trails, and recreation like kayaking or wildlife spotting is popular on the river.

You said:

“Macon is known for its music. Otis Redding singing “Sitting on the Dock of the Bay”, has a memorial to him on the Ocmulgee Water Trail.”

“Macon and Bibb County are most fortunate to have the Ocmulgee River as a main feature to enjoy and appreciate. It is a learning tool for students and grownups on how to use and take care of it.”

“The Ocmulgee (“Bubbling Waters”) River is rich in history and has played a major part in the development of Macon and the surrounding area.”

Bend, OR

Bend is a popular destination for its outdoor recreation on the Deschutes River. Activities include kayaking, tubing and swimming, and walking or biking on paths along the river. The river holds great importance to the community.

You said:

“The Deschutes River defines our landscape and much of our community character.”

“It makes Bend, Bend.”

“Great downtown area with access to the river. What could be better?”

In addition, Oregon had a number of Best River Town submissions along the Willamette River including Portland, Corvallis, Eugene, and Independence.

Missoula, MT

Missoula was certainly one of the less surprising responses on the list. Located at the junction of the Clark Fork, Black Foot and Bitterroot Rivers, it is well-known for its recreation, including rafting, kayaking, and local exploration for those interested in nature, history and geology. The area is also an excellent spot for family gatherings and picnics.

You said:

“A gem of Montana.”

“World-class fishing, rafting with unmatched beauty. Plenty of family gathering & picnic locations. Pristinely clear water and pine-fresh air. Nearby points of interest for history buffs, geologists, naturalists, and archeologists.”

“These are some of America’s best trout rivers and are also outstanding float and kayaking waters with some of the best scenery anywhere. The town loves the rivers and they make the town special.”

Disclaimer

In sharing the results of our research on America’s best river towns, we hope to shine a light on communities that not only thrive because of their local rivers, but strive to give back to them. While we are not advocating for traveling to these locations, should you choose to do so, we hope you take into account these towns’ community engagement efforts with their rivers. If you visit, we hope you acknowledge those efforts through responsible tourism and respectful, sustainable engagement with the rivers.

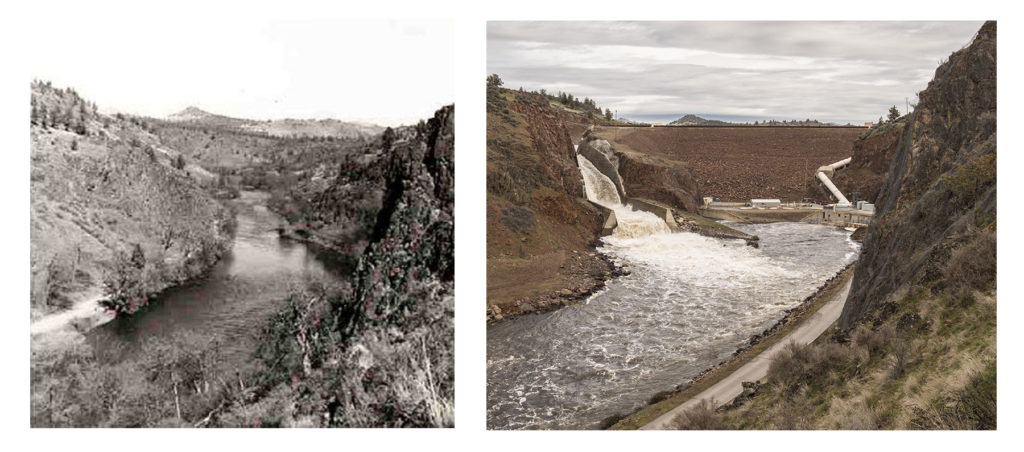

There are major efforts underway that would have a transformational impact on river health, removing dams and restoring healthy, free-flowing rivers nationwide. American Rivers is a strong advocate for both the 21st Century Dams Act and the removal of the four dams on the lower Snake River as top priorities for Congress and the Biden Administration.

While these are separate efforts, they have grown from a consistent philosophy that we must balance hydropower and healthy rivers.

The bipartisan 21st Century Dams Act includes provisions applicable to the majority of the 90,000+ dams in the country but does not include funding to remove hydropower dams owned by the federal government, as those dams generally need individual authorization and legislation.

The proposal to remove the four federal dams on the lower Snake River addresses the urgent needs in the Columbia Basin with that individual negotiated approach. Both efforts are necessary and timely, as Congress and the Biden Administration consider national infrastructure investments.

Why is it urgent for Congress and the Biden administration to address dams now? Dams have devastated river health nationwide, impacting rivers, fish and wildlife populations, and cultural resources. As dams age and flood magnitudes increase with climate change, many dams become public safety hazards. Dams are infrastructure and should be part of any federal infrastructure legislation.

In the Pacific Northwest hydropower plays a more significant role in the energy mix than in any other region of the country. There are roughly 150 hydro projects in the Columbia Basin alone. The damming of rivers has devastated salmon runs and the Indigenous people who depend on salmon for their food, culture and livelihood. Many salmon and steelhead runs and other culturally significant aquatic species are now endangered or extinct. The entire web of life, from cedar trees to eagles to orcas, is suffering the impacts.

As we confront climate change, which poses an existential threat to life on our planet, it is critical that we balance our energy needs with our need for healthy rivers. We’re making progress on three fronts

The 21st Century Dams Act

Representative Annie Kuster (NH-02) introduced the 21st Century Dams Act that advances the environmental, safety, and economic benefits of healthy rivers and charts a course for hydropower in our nation’s future. The bill, which provides $24.8 billion in spending over 5 years, is designed to accelerate the rehabilitation, retrofit, or removal of the nation’s more than 90,000 dams. Rep. Kuster was joined by Representatives Don Young (AK-AL), Kim Schrier M.D. (WA-08), Julia Brownley (CA-26), Jared Huffman (CA-02), Debbie Dingell (MI-12), Emanuel Cleaver (MO-05), Nanette Diaz Barragán (CA-44), Bonnie Watson Coleman (NJ-12), and Scott Peters (CA-52) in introducing this legislation. Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-CA) introduced companion legislation in the Senate, together with Alex Padilla (D-CA), Ron Wyden (D-OR), Debbie Stabenow (D-MI), Gary Peters (D-MI), Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY) and Michael Bennet (D-CO).

American Rivers played a key role in crafting the legislation, with vital partnership from organizations including the Association of State Dam Safety Officials, American Whitewater, Trout Unlimited, The Nature Conservancy, Hydropower Reform Coalition, Low-Impact Hydropower Institute, National Hydropower Association, and others.

If enacted, the bill – which is not focused on any particular U.S. dam, river or region – would reopen more than 10,000 miles of rivers and enhance their climate resilience by removing 1,000 dams, and also rehabilitating hundreds of the nation’s most hazardous dams. The legislation would also secure the nation’s existing hydropower dams by improving their performance, resilience, and safety. Additionally, it would provide a significant investment in existing federal dams to enhance environmental performance and improve dam safety. Collectively, these efforts will support or create approximately 450,000 jobs.

National infrastructure legislation

The bipartisan infrastructure bill that the Senate passed earlier this month contains critical investments for clean water and rivers The infrastructure bill includes $1.6 billion for dam removal and dam safety — a necessary down payment for restoring healthy, free-flowing rivers and protecting communities from outdated, dangerous dams. It does not include the full funding for dam removal, retrofits and rehabilitation provided by the 21st Century Dams Act, but it’s an important step. Additionally, there is $743 million included for hydropower dams to do environmental improvements, dam safety, or grid resilience projects.

Snake River Salmon Recovery

Based on their staggering cost — financial, ecological and cultural — the four federal dams on Washington’s lower Snake River should be removed. The overwhelming scientific evidence states that the only way to stem the slide toward extinction and recover Snake River salmon and steelhead is to remove these four dams.

Native American tribes across the Northwest are advocating for a Snake River salmon recovery solution that includes lower Snake dam removal along with robust investments in clean energy, transportation and agricultural infrastructure. We stand with the tribes and fully support their efforts.

American Rivers is calling on Northwest leaders and the Biden administration to take immediate action and secure funding for these solutions in the 117th Congress. Salmon and communities cannot wait any longer. It’s why we named the Snake River America’s Most Endangered River® for 2021. The time for action is now.

We encourage our partners and supporters to contact their members of Congress to support these legislative efforts, all of which embrace pragmatic problem solving to restore rivers, chart a course for hydropower and strengthen communities.

This week’s release of the first part of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s sixth assessment report details how the impacts of climate change, including floods and drought, are real and will get worse without bold action. According to the IPCC, “the world will see serious climate impacts with [an increase of] 1.5°C”.

As American Rivers President Tom Kiernan said, “From persistent drought and smaller snowpack reducing river flows across the Southwest, to rising temperatures killing Northwest salmon and increasingly frequent and severe floods in the Midwest and Eastern states, frontline river communities are feeling the pain. Black, Latino and Indigenous communities face disproportionately higher impacts due to centuries of disinvestment and unjust policies and practices.”

We need to pull out all the stops and drastically reduce emissions to limit warming beyond 1.5°C. And, we need to redouble efforts to protect and restore healthy, free-flowing rivers and sustainable water supplies that can provide community resilience and a first line of defense against climate impacts.

Here’s how climate change is already impacting rivers, communities and water resources:

Water scarcity and insecurity: Climate change can increase the duration and intensity of drought conditions leading to reduced precipitation, river instream flows, and groundwater recharge. This will reduce water supplies for people, recreation, agriculture and industry, . Low instream flows — or not enough water in the river — degrade habitat and are lethal to aquatic species because water tends to be warmer when there is less of it.

Increased flood risk and polluted stormwater runoff: Increased intensity and frequency of storms increase flood risk for vulnerable communities and increase polluted stormwater runoff that threaten community health, water supplies and river habitat.

Increased pressure on infrastructure: Traditional infrastructure like dams and levees degrade overtime and are struggling to keep up with more frequent and intense storm events caused by climate change. This could lead to catastrophic failures that pose serious flood risk for communities.

Elevated water temperatures: As the climate warms, water temperatures can rise to lethal levels for aquatic species and because of fragmentation from dams etc, species are less able to migrate american rivers rootidto healthier habitats. Warmer waters can also cause toxic algae outbreaks that can contaminate water supply, make people and animals sick, and kill sensitive aquatic and land species.

Reduced watershed health: Climate change is causing our watersheds to change – forests are more prone to wildfires, soils are more prone to erosion and elevated temperatures can increase the spread of undesirable species like the Mountain Pine Beetle. Without healthy forests, our watersheds become destabilized and the quality and quantity of the water entering our rivers is reduced.

Change in traditional use: Whether you are a tribal member, farmer or city manager, climate change is going to influence how you use water in the future. It could impact whether you are able to harvest fish from your usual and accustomed grounds, the types of crops you grow, the amount of water available for residents in your communities or determine where you live and work. Regardless of the circumstance, the change will be difficult and require unprecedented cooperation as we adapt to a new and ever-changing reality. How humans respond to climate change impacts will directly involve and impact rivers and communities.

Those impacts are real. But just as rivers embody climate threats, they’re also the source of powerful solutions. A healthy river can be a community’s first line of defense against climate impacts, offering clean water supplies, cost-effective flood protection, safe places to recreate and stay cool, and connection to culture.

Rivers have always been a source of hope and strength. Now, the stakes couldn’t be higher. In an era of climate change, communities with healthy, free-flowing rivers with clean water will be the ones that thrive. We must insist that all communities, and not just a privileged few, benefit from healthy rivers now and in the decades to come.

This is no time to give up or give in. We must respond to climate change and act now.. There is still so much good we can do, together.

As communities across the country are facing needed upgrades to their water infrastructure, many are turning to green stormwater infrastructure (GSI) for a more integrated approach to clean water, greening, and public health. But GSI presents some unique challenges to existing pathways for public infrastructure funding. At the same time, there are unique benefits that, if visible, can be leveraged to draw support from the private sector.

American Rivers introduces the Gateway Garden model as an innovative approach to attracting private investment to benefit communities and help municipalities overcome stormwater management challenges. Gateway Gardens are a type of GSI that is strategically located at the entranceway or “gateway” to a community for maximum visibility. They provide opportunities for local businesses to invest in clean water projects in exchange for the direct benefit of sign advertisement and the indirect benefit of an enhanced community.

The Need for More Visible Green Stormwater Infrastructure

Water infrastructure in the United States is failing. As flooding events increase in the face of climate change this is especially true for stormwater infrastructure. The American Society of Civil Engineers gave the nation’s stormwater infrastructure a D grade in 2021, and our stormwater systems will only continue to rapidly decrease without investment in more sustainable solutions. A proven method of managing stormwater pollution and decay is through green infrastructure projects. Green Stormwater Infrastructure (GSI) has a multitude of benefits that don’t just include managing polluted stormwater, although GSI has become the preferred method for doing so. GSI sites also beautify neighborhoods, increase livability, lower the heat index, and create a sense of security and safety for community members.

Oftentimes, however, GSI sites are placed in such a way that the non-stormwater related benefits are not visible to most within the community. GSI sites are frequently chosen for their ability to manage stormwater, and for how easily they’re paid for and maintained. So, sites such as schools, municipal buildings, and private residencies are oft used locations for GSI. These traditional sites are wonderful for stormwater remediation, but often don’t showcase the additional benefits GSI provides to the entire community the way a Gateway Garden can. By attracting the support of businesses for GSI, Gateway Gardens can help to offset the misconception that GSI projects are too expensive an undertaking.

The Gateway Garden Concept

We need to rethink the way we implement GSI. One solution to the low visibility of GSI is the “Gateway Garden” concept. They serve as not only a way to manage stormwater, but also as a community meeting place, a source of pride, and a beautiful entrance to a neighborhood. Gateway Gardens are designed to meet stormwater permit requirements, ensuring they still perform their primary function of stormwater management while creating opportunities for community engagement. Gateway Gardens’ highly visible approach to stormwater management lends to a cascading effect. The more visible the Gateway Garden, the more likely more GI projects will be implemented throughout that community. A Gateway Garden can be the first step into revitalizing a community that is plagued with the harms of poorly managed stormwater.

The core concept of Gateway Gardens is sustainability. Environmentally the benefits of GSI projects are well understood. GSI projects are the gold standard for how to manage stormwater in a sustainable way. But Gateway Gardens also add new elements of sustainability, including social stability, which thrives under the Gateway Garden concept. Creating a community place of engagement has been proven to increase feelings of safety and a sense of oneness within a neighborhood. A neighborhood that has a sense of community is more likely to endure and thrive. Gateway Gardens not only give all the benefits of a well-managed GSI project, but also give the area that they serve the invaluable sense of community we all strive for.

Paying for Gateway Gardens

Gateway Gardens’ most key element is sustainability. This is true throughout the product and is especially true in the innovate financing model. Gateway Gardens are financed through a public/private partnership system. Given the highly visible nature of Gateway Gardens, it makes for premier advertising space for local business owners. This financing structure is key to the success of a Gateway Garden. American Rivers asked business owners in Lancaster County Pennsylvania about their likelihood to finance a project such as Gateway Garden, and found them overwhelmingly willing to support creating and maintaining Gateway Gardens in exchange for advertising space. Business owners also get the added benefit of being seen as cornerstones of the community that they help to finance a Gateway Garden in. Given the additional benefits, the business owners are also improving the livability of the communities they help to finance Gateway Gardens in, and the community will easily see the positive impacts the gardens have through the support of the business.

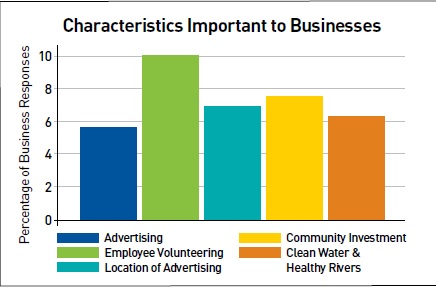

In the previously mentioned survey, business owners stated that community investment, volunteering as members of the community, and clean water were even more important factors than the location of the advertising. The business partnership also helps to alleviate one of the greater barriers to GSI projects in underserved communities, that being the cost. With the help of municipal governments and local businesses, Gateway Gardens can be a cornerstone of any neighborhood.

Gateway Gardens is the Kind of Innovation Communities Need

American Rivers presents the Gateway Garden concept as a new idea for community leaders to explore and adapt to their own cities and towns. These innovative projects work with their communities to build the kind of aesthetics that reflect their needs. These innovative projects work with their communities to build the kind of aesthetics that reflect their needs. Gateway Gardens work with the local businesses and municipalities to create a sustainable model that will be the cornerstone of a neighborhood for the foreseeable future. For the first steps to making a Gateway Garden in your community, see the American Rivers’ brochure.

It’s hard not to get excited about the investment included in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Framework. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act would invest $55 billion in water infrastructure, $12 billion for flood management and over $4.5 billion for watershed restoration. However, our 2021 Blueprint for Action report recommends investing $200 billion for improving water infrastructure, $200 billion for modernizing flood management, and $100 billion for restoring watersheds in our community.

The Biden administration has reenergized and spurred Congress to recognize and address the myriad of water resources issues that require federal investment. Now that the Senate has passed on the Bipartisan Infrastructure Framework, the House will get the chance to come up with their own proposal. It’s worth remembering that the House included over $104 billion for water infrastructure compared to the Bipartisan Infrastructure Framework (based on S. 914) which included $55 billion for water infrastructure.

Water Infrastructure

These numbers may seem exorbitant, but investment in our water resources is long overdue. In 1977, 63 percent of total capital spending for water and wastewater systems came from federal agencies; today that number is less than nine percent. There are over two million people who lack access to running water or basic indoor plumbing, which disproportionately affects Black, Latino and Indigenous communities. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act provides over $43 billion for the Drinking Water and Clean Water State Revolving Funds (SRF). Importantly, there is a provision that reduces the state cost share for the first two years to 10 percent and directs 49 percent of the funding to be administered as grants and completely forgivable loans.

This investment will not only fund programs for small and disadvantaged communities ($510 million), sewer overflow and stormwater reuse grants ($1.4 billion), and the Indian Reservation drinking water program ($250 million), it will also fund studies on advanced clean water technologies, stormwater infrastructure technology, and historical funding distribution to small and disadvantaged communities.

American Rivers supports increased funding for water infrastructure in any bipartisan infrastructure package, including:

- $10 billion per year for the Clean Water State Revolving Fund

- $10 billion per year for the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund

- A minimum of 20% of SRF funding for additional subsidization for disadvantaged communities

- A minimum of 20% of SRF funding for the Green Project Reserve

Flood Management

As the Bipartisan Infrastructure Framework continues to evolve, it’s essential that infrastructure projects are not placed in the floodplain and are designed to be resilient to future floods. Climate change has normalized more frequent and intense weather events exacerbating flooding and displacing many and causing billions of dollars of damage to property. These issues are not subsiding anytime soon, and existing flood management practices are not built to withstand worsening floods. Congress has responded by including sizable investments in flood management, including for Flood Mitigation Assistance ($3.5 billion), Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities ($1 billion), Federal Assistance to FEMA ($2.2 billion), and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers inland flood management ($2.5 billion). Moving forward, we must continue to promote equitable, integrated flood management and prioritize nature-based approaches to managing floods.

American Rivers supports increased funding for flood management in any bipartisan infrastructure package, including:

- $10 billion over five years for the FEMA BRIC program, with 20% set aside for natural infrastructure projects

- $5 million annually for the Federal Interagency Floodplain Management Task Force

- $5 billion for flood mapping programs with FEMA

- $50 million annually for Flood Plain Management Services with the U.S. Army Corps.

Restoring Watersheds

Dams are a part of the 2 million barriers that prevent fish from migrating upstream and alter the natural conditions of rivers and watersheds. Removing vulnerable dam structures is a multi-purpose, multi-benefit approach that will allow rivers to slowly return to a natural riverine habitat and also prevent old and unmaintained dam failures. The bill includes $1.6 billion for dam removal and dam safety — a necessary down payment for restoring healthy, free-flowing rivers and protecting communities from outdated, dangerous dams. Additionally, there is $743 million included for hydropower dams to do environmental improvements, dam safety, or grid resilience projects.

Our watersheds are also threatened by a changing climate. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Framework provides an opportunity to restore and manage our watersheds and contribute to President Biden’s ambitious goal of conserving 30% of land and water by 2030. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act would provide the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service with $255 million, including $162 million for the Klamath Basin. The Bureau of Reclamation would receive $200 million for multi-benefit projects and management related to watersheds, the U.S. Army Corps would receive $2 billion for Ecosystem Restoration, and the Natural Resource Conservation Service would receive $468 million for watershed programs.

American Rivers supports increased funding for watershed restoration in any bipartisan infrastructure package, including:

- $1.6 billion for Dam Safety and Dam Removal programs

- $743 million included for hydropower dams to do environmental improvements

- $1 billion to the NRCS Emergency Watershed Protection Program

- $1 billion for the Habitat Conservation Program with NOAA

- Ensure that all infrastructure funding prioritizes resilient and nature-based solutions such as restoring wetlands, rivers, streams and watersheds, floodplain restoration and reconnection, and that new projects and repairs restore natural functions and features wherever practicable.

It is also worth acknowledging Western Water Infrastructure would receive $8.3 billion, funding programs related to aging water infrastructure ($3.2 billion), water storage ($1.15 billion), water recycling and reuse ($1 billion), the waterSMART program ($400 million, with $100 million for natural infrastructure), and drought contingency plans ($300 million).

While investments of this size are a promising start, they are only the first step. Now is the time to make the necessary, equitable investment to remedy historical disenfranchisement, address pressing water resource issues, and prepare for the future problems that will be driven by climate change.

We tend to think of history as a rigid, academic discipline, measuring specific events against linear time, painstakingly verifying them with artifacts and other records. The recent discovery of artifacts unearthed at a site known today as Cooper’s Ferry along Idaho’s Salmon River carbon-dated back 16,500 years. This was big news, establishing Cooper’s Ferry as one of the oldest verified sites of human presence in North America.

Cooper’s Ferry is in the heart of Nez Perce Tribal country, and is a part of the vibrant living culture of the tribes. For many Nez Perce people, the celebrated discovery there served mostly as contemporary science’s confirmation of a story they already know. Narrative histories and traditions of Nez Perce people—Nimiipuu—tend to be based on a different kind of chronology, one that says Nez Perce people have always been in this land, or more accurately, of it. The Cooper’s Ferry site has a name in Nez Perce—Nipehe. It lies in the heart of the sprawling, 260,000 square-mile Columbia-Snake River Basin, the greatest salmon and steelhead producers in the world. Historically.

Treaties among nations are part of our history and are the supreme law of the land in the US Constitution. In 1855 the US Government made treaties with the sovereign nations of the western United States: Nez Perce, Umatilla, Warm Springs, and Yakama among them. Those nations ceded millions of acres of their homelands to the United States in return for protection, and they retained the right to hunt and fish at their usual and accustomed places.

While the treaties – which are contracts among nations — guaranteed fishing and hunting in the usual and accustomed places, subsequent court decisions known as Boldt 2, also guaranteed habitat. In other words, part of our joint contract is that there be fish to catch and game to hunt. We cannot make a contract that people can fish and then turn around and wipe out the fish.

These treaties are contracts that bind and obligate each citizen of the United States: we cannot take actions that cause salmon to go extinct and when we learn that we are doing that, we have to fix it. The United States gained much when the Treaties were signed – just look around us – and in return we make sure there’s salmon in the rivers. This benefits all of us, and is a promise we made. Let’s keep it.

While the “usual and accustomed” places doctrine guarantees the rights, sadly it couldn’t guarantee the places. The hydroelectric dam era in the Columbia-Snake Basin, ushered in by Bonneville Dam in 1938, now includes some 150 projects including 18 on the Columbia and Snake mainstems. Many populations of fish species at the center of Native cultures such as wild salmon, steelhead and lamprey, are perilously close to being lost forever. People representing countless cultures and histories living now in the Northwest believe removal of four federal dams on the lower Snake holds the key to unlock the recovery potential.

For so many people today, it’s impossible to begin to fathom much less understand what the places once were. We haven’t witnessed it, much less experienced it ourselves. That’s one of the invaluable perspectives the timeless narrative histories of Northwest Native people can offer all of us: they have.

We view restoring the lower Snake River – a living being to us, and one that is injured – as urgent and overdue. Congressman Simpson, in focusing on the facts and on a solution, speaks the truth – that restoring salmon and the lower Snake River can also reunite and strengthen regional communities and economies. We will support Congressman Simpson’s initiative and we respect the courage and vision he is showing the region. This is an opportunity for multiple regional interests to align with a better future for the Northwest: river restoration and salmon recovery; local and regional economic investment and infrastructure improvement; and long-term legal resolution and certainty.”

— Nez Perce Chairman Shannon Wheeler said in a statement supporting Idaho Congressman Mike Simpson’s February proposal for a Northwest infrastructure package that includes removing the four lower Snake River dams.