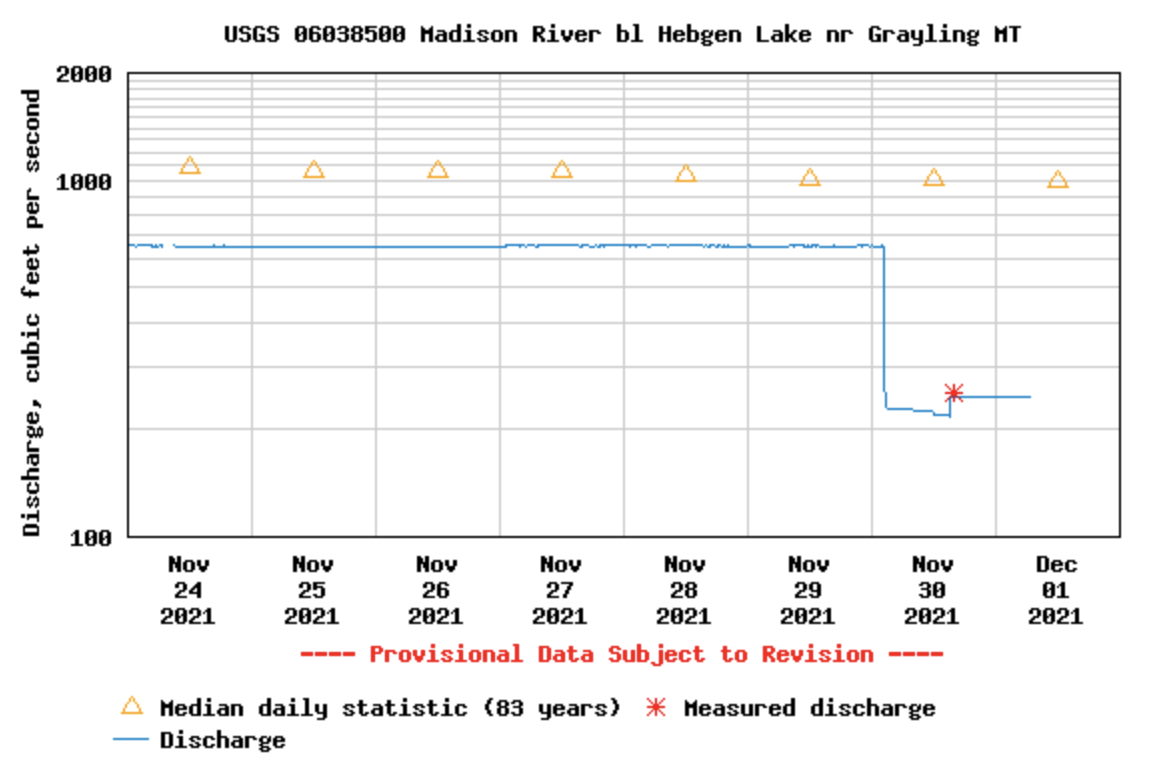

Northwestern Energy’s 107-year-old Hebgen Dam on Montana’s famed Madison River suffered a malfunction early on Tuesday morning that sent flows below the dam plummeting from 650 cubic feet per second (cfs) to nearly 200 cfs almost instantly.

I surveyed the damage earlier today and saw numerous side-channels that had dried up, stranding fish and exposing dozens of recently created brown trout redds (nests), especially in the reach between Hebgen Dam and Quake Lake. Unless the dam is fixed and flows are restored in the next 24 hours, the ecological damage to the river and its world-renowned wild trout fishery could be very significant. The photos below show the same spot on the river below Hebgen Dam on Sunday and earlier today, with water levels significantly diminished.

Unfortunately, it’s too late to undo the damage that’s already been done to the Upper Madison River and its fishery. But thanks in large part to American Rivers’ advocacy, the infrastructure bill that was just signed into law by President Biden includes $2.4 billion dollars to improve dam safety, make environmental upgrades at dams, and remove harmful dams that have outlived their purpose.

Over 10 million residents in the West get their drinking water from rivers originating on public lands, and according to the Natural Resources Conservation Service, 80 percent of all wildlife species, including migratory birds, rely on riverside lands at some stage in their lives. At the same time, nearly one-third of freshwater species face extinction worldwide, in part due to pollution. As such, streams with exceptionally high water quality, and the benefits they provide to fish, wildlife, and people, are some of the most important places we can protect across the country.

Many of Colorado’s headwaters streams contribute vital, high-quality water for people, agriculture, and wildlife downstream. This clean water is not only important to the overall health and resilience of the rivers in the region but by extension the health of the communities, ecosystems, and economies connected to it. As we move into a future of increasingly disruptive climate uncertainty, and as streams with exceptional water quality become disturbingly rare, it is more important than ever to protect such sources of water that provide resiliency for both people and the environment.

The Clean Water Act gives individual states the authority to designate Outstanding National Resource Water protections for waterways with exceptionally high water quality to ensure that their water quality is not degraded. Colorado’s state-level Water Quality Program includes a robust anti-degradation provision, the most rigorous of which is designated as “Outstanding Waters” (OW). For a river stretch to be considered “outstanding” it must meet 12 water quality standards, have outstanding natural resource values such as aquatic life habitat or recreational use, and be threatened by outside impacts requiring additional protections. OW designations also require robust community outreach and support for potential stream reaches. The Colorado Water Quality Control Commission (WQCC) reviews each river basin across the state for new designations on a triennial schedule.

The triennial review for streams within the Animas, Dolores, San Juan, San Miguel, and Gunnison River basins began in 2020. American Rivers has partnered with American Whitewater, Colorado Trout Unlimited, Conservation Colorado, Mountain Studies Institute, High Country Conservation Advocates, The Pew Charitable Trusts, San Juan Citizens Alliance, Trout Unlimited and Western Resource Advocates to examine streams in these basins that are the highest quality and deserving of increased water quality protections by the State. Over the past year and a half, groups have been collecting water quality data for potential OW stream candidates, documenting natural resource values, and meeting with local stakeholders to gather community support.

Our coalition is proposing 17 streams to the Water Quality Control Commission for new OW protections in these basins. These stream reaches provide critical aquatic habitat for native trout species, macroinvertebrates (that is, bugs), birds, and other wildlife; provide significant contributions to downstream resilience and ecosystem services like high-quality drinking and irrigation water and provide exceptional recreational opportunities like fishing, swimming, and paddling. Since 2020, volunteers and staff have been collecting water samples for analysis from all 17 streams, four times per year – even visiting somewhat frozen streams in winter.

Over the last two years, American Rivers and our partners have been presenting the data supporting our list of candidate streams to the WQCC during their annual hearings. In the coming months, we will conduct additional water quality sampling and finish up our outreach to the communities surrounding these streams in preparation for the final hearing for the Gunnison-San Juan region, slated for June 2022.

For more information, or if you’d like to get involved, please contact Mike Fiebig, Southwest River Protection Program Director, or Fay Hartman, Southwest Region Conservation Director.

“Atmospheric rivers” have been slamming the U.S. West Coast for the last several weeks, causing tremendous damage and placing many communities and families in harm’s way. Even as we write this blog, many homes, farms, businesses and other infrastructure in Washington and British Columbia remain underwater from record rains that fell through November 15, 2021. Many are just beginning to grapple with damages, and our hearts extend to those who are affected.

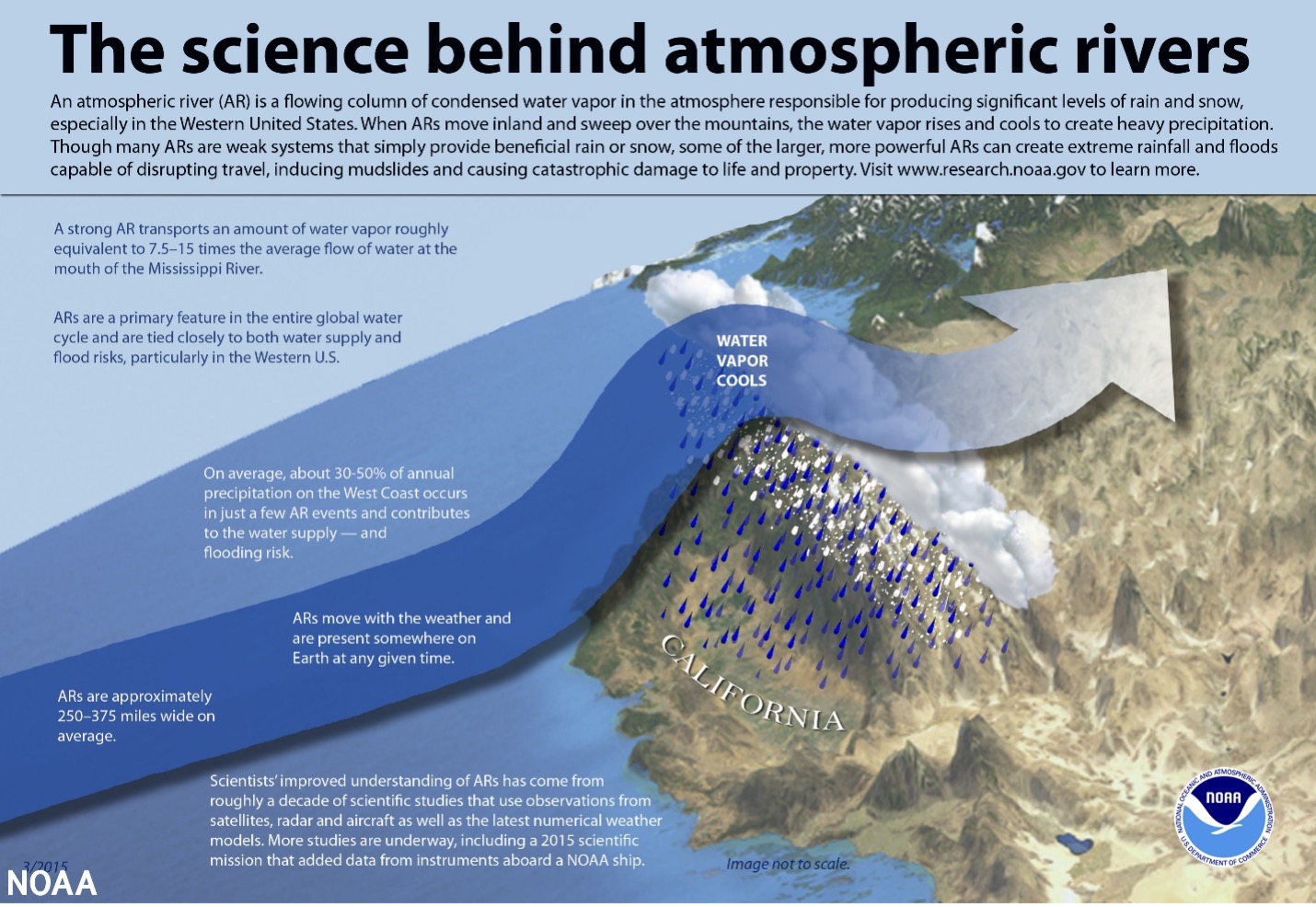

The long narrow bands of warm water vapor that constitute atmospheric rivers extend far out into the Pacific Ocean and carry vast amounts of water. A strong atmospheric river can transport 7.5-15 times the average flow of water at the mouth of the Mississippi River.

NOAA infographic on the atmospheric rivers

During October 23-26, 2021 one of these storms dropped 7.6 trillion gallons of rain on northern California, causing mudslides, power outages and flooding across the state. According to a statement from the National Weather Service’s Western Region Headquarters, “that’s enough water for over 244 million people for an entire year.”

Washington state caught the edge of this storm which inundated the region with rain — saturating soils and increasing water levels. More rain has fallen in the past week than usually falls in the entire month of November. So, when another atmospheric river directly hit Northern Washington this past weekend, many systems reached their capacity.

The Sumas, Nooksack and Skagit Rivers were hit the hardest, with the Nooksack, northwest of Bellingham, reaching its highest flood elevations in recorded history. Interstate 5 north of Bellingham was shut down for several hours and over 500-people were displaced, and even more were without power. In the Town of Sumas, at the U.S.-Canadian border, 75% of structures have been damaged. On Monday, Gov. Jay Inslee declared a severe weather state of emergency in 14 Western Washington Counties.

Thankfully these areas have experienced local floodplain managers and good emergency response systems in place. But even with this experience and planning, communities are struggling to keep with the impacts of climate change.

These types of storms are only expected to increase in intensity and severity with climate change. Historically, about 30-50% of annual precipitation on the West Coast comes from atmospheric rivers and they are critical to sustaining a healthy snowpack and maintaining the water supply throughout the year. However, as the climate warms, more of this precipitation will fall as rain and not as snow, meaning that it will come all at once instead of being metered out over several months as the snow melts in the spring – contributing to increased runoff volumes and larger floods.

At the same time, the population of Washington state is expected to double in the next 50-years creating added development pressure in flood prone areas. Places like the Nooksack and Skagit are largely agricultural but are at risk of being converted into residential housing.

Farmers across the region have been dealing with floods for decades and it can cause very real financial, social and emotional damage. In addition to impacting the land and structures, large scale flooding like this can damage the infrastructure and supply chains that farmers rely on. Multiple rail lines were washed out in the recent storm so farmers cannot get their grain products to the mill. Additionally, impacts to feed providers means securing reliable sources of food for livestock will be increasingly difficult.

While the agricultural industry was seriously impacted by flooding and climate change, the very nature of farming means that there are fewer people and structures at risk when floods occur. When farmland is converted to residential housing, the number of structures, impermeable surfaces, and people in the floodplain increases putting more people and property in harm’s way.

New development under construction in the Skagit shown during flooding on November 16, 2021. Photo Credit: Brandon Parsons, American Rivers with aerial support by LightHawk.

Floodplains also provide critical natural and beneficial functions for the environment. In their natural condition, floodplains store floodwaters, helping to recharge groundwater levels and provide critical habitat for threatened and endangered salmon species.

Communities all over Washington state are embracing the idea of integrated floodplain management that aims to improve the resiliency of floodplains for the protection of human communities and the health of the ecosystem while supporting values important in the region such as agriculture, clean water, a vibrant economy, and outdoor recreation. This approach looks at the entire river or watershed to understand the different dynamics of flooding and the diverse needs represented in the floodplain. By working collaboratively across interests, solutions can be developed to address flood risk while also supporting agriculture, salmon restoration, Native American Treaty rights and responsible economic development. Not every project can mean a win for every interest, but with strategic vision and benefit-sharing, the idea is that we are working collaboratively towards a watershed system that can, over time, function better for people, fish, farms and cities.

Funding through the Infrastructure Investment & Jobs Act presents an unprecedented opportunity to not only make meaningful investments in integrated floodplain management but to align programs to address shared challenges. As new funding guidelines are developed and new projects are initiated, it will be critical for agencies to allow flexibility in funding streams that support multiple opportunities in the floodplain and address long term flood risk in a more comprehensive manner.

While there are policy and funding solutions that can help affected communities recover and reduce risk long term, it is local residents that are helping each other most now. People from all over northern Washington are opening up their homes to people displaced by these floods, donating food and standing side by side to help people recover. It is people’s compassion for their neighbors and willingness to step up in times of need that stands out most during times of hardship.

If you are interested in supporting those affected by recent flooding, here is a list of organizations on the ground that are assisting residents

After President Biden announced his American Jobs plan, we spent months engaging with Congress as they carefully formulated a once-in-a-generation investment in infrastructure across every sector. On Monday, November 15th President Biden signed into law the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), capping a long and painstaking process that includes critical investments in rivers and clean water infrastructure, but it was well worth it.

Improve Water Infrastructure

Our nation is facing a water infrastructure crisis throughout every piece of our water system – drinking water, wastewater and stormwater. Two million people in our country do not have access to safe, clean, affordable drinking water. The nation-wide water infrastructure crisis now has $55 billion in funding to replace aging infrastructure, remove lead service lines and address emerging contaminants like PFAS/PFOA. The IIJA also includes:

- $23.4 billion for the Drinking Water and Clean Water State Revolving Funds,

- $10 billion to address PFAS/PFOA

- $15 billion for lead service line replacement,

- $3.5 billion for Tribal water and sanitation infrastructure

- $510 million drinking water Assistance for Small and Disadvantaged Communities,

- $1.4 billion for Sewer Overflow & Stormwater Reuse Municipal Grant Program, and

- A directive for the EPA to conduct a needs assessment for nationwide low-income water assistance, a necessary step for eventually setting up a permanent low-income water assistance program

Modernize Flood Management

Climate change has steadily increased the frequency and intensity of natural disasters and extreme weather events. The IIJA provides necessary funding to build resilience in vulnerable communities and mitigate impacts through sustainable efforts like nature-based solutions. The IIJA includes:

- $3.5 billion for Flood Mitigation Assistance program,

- $1 billion for Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities program,

- $300 million for the Emergency Watershed Protection Program, and

- $2.5 billion for inland flood risk management at the Army Corps, with a focus on multi-purpose projects and projects that will directly benefit economically disadvantaged and minority communities.

Restore Watersheds

Healthy, free-flowing rivers provide a vital source of freshwater, biodiverse habitats for wildlife, and a place to enjoy nature and bring us together. However, 44 percent of waterways in the U.S. are too polluted for fishing and swimming. The IIJA will help restore and conserve our rivers by investing $4.5 billion towards watershed restoration, including:

- $618 million for Natural Resource Conservation Service watershed programs,

- $400 million for NOAA Community-based Restoration Program: Fish Passage Barrier Removal Grants,

- $491 million for Habitat Restoration and Community Resilience Grants,

- $172 million for the Pacific Coastal Salmon Recovery Fund

Manage Western Water

Throughout the west, water scarcity threatens the delicate balance of limited water resources for drinking water, irrigation and recreation. The IIJA invests $8.3 billion across western watersheds and river basins through the Bureau of Reclamation. Funding will help implement large water reuse and recycling projects, increase resilience to climate change, and prioritize natural infrastructure solutions. The IIJA also includes:

- $100 million for the Cooperative Watershed Management Program,

- $115 million for Aquatic Ecosystem Restoration Program,

- $2.15 billion water storage, recycling and reuse,

- $400 million for waterSMART Water and Energy Efficiency Grants, including $100 million for natural infrastructure, and

- $300 million for Drought Contingency Plans.

Rehabilitate, Retrofit and Remove Dams

American Rivers is co-leading in the passage of the Twenty-first Century Dams Act, which calls for $23.3 billion to accelerate the rehabilitation, retrofit, and removal (the “3Rs”) of the nation’s more than 90,000 dams to improve public safety, enhance clean energy output, and restore the health of our nation’s rivers. The IIJA chips away at the funding called for in the Twenty-first Century Dams Act by investing $2.4 billion to support the removal, rehabilitation and retrofit of dams, including:

- $800 million for dam removal,

- $800 million for dam safety, and

- $753 million for hydropower facilities for dam safety improvements, environmental improvements, and grid resilience.

What’s next?

Now, the Senate must act with urgency to rectify their concerns in the Build Back Better Act (BBBA) and pass legislation true to President Biden’s Build Back Better framework. This framework provides additional funds to address the water crisis facing communities nationwide – lead service line replacement, low-income rate assistance and climate-resilient infrastructure.

Even with the behemoth IIJA and BBBA, Congress needs to take additional urgent steps to protect clean water and rivers nationwide:

- Enact legislation to save Northwest salmon from extinction by restoring the lower Snake River and investing in the region’s energy, transportation and agriculture sectors

- Pass the bipartisan 21st Century Dams Act, which dedicates $25.8 billion for the removal, rehabilitation and retrofit of dams, including $7.5 billion to support removal of 1,000 dams to restore 10,000 miles of rivers.

- Pass bills that would designate more than 6,700 miles of new Wild and Scenic Rivers in New Mexico, Washington, Montana and Oregon.

The Sierra Nevada mountains are the source of more than 60% of California’s water, with much of that originating in small headwater streams. Unfortunately, the water supply and water quality coming from these streams is at risk from record setting wildfires, climate change, loss of riparian habitats, and the extensive network of forest roads.

The national forests of the Sierra Nevada include nearly 47,000 miles of forest roads. While they provide important access to the Sierra Nevada, especially for fuels treatments and firefighting, this road network negatively impacts our water supply and water quality by transporting eroded sediment and runoff to waterways. In fact, forest roads are the main source of chronic sediment pollution in our headwaters. Even a quarter mile of dirt road could be losing 20 to 40 tons of sediment every year. That’s three to five dump trucks full of dirt annually!

Fortunately, there are road improvements we can make that help reduce sediment transport to waterways. First, we can decommission forest roads; restoring the topography and natural processes that the road disrupted. This is ideal for roads that are no longer in use, are redundant, or that cross sensitive habitats like mountain meadows. Where decommissioning is not feasible, we can still make significant improvements to our forest roads through drainage treatments like adding gravel, constructing rolling dips and water bars, and replacing or removing undersized culverts. These features all help to make the road “hydrologically neutral” and disconnect the road drainage system from nearby waterways. Even simply blocking roads from vehicle traffic helps to slow erosion and the pollution of our streams.

American Rivers’ Forest Road Work in the Sierra Nevada

American Rivers is working with partners in the Sierra Nevada to improve our forest road system to help ensure the resiliency of California’s rivers and water supply. In partnership with the US Forest Service, and with support from the California State Water Resources Control Board, American Rivers recently completed a successful project in the North Yuba River watershed that constructed drainage improvements on 26 miles of roads and decommissioned another 6 miles. Our analysis of these treatments found that we reduced roadway erosion and sediment runoff into nearby streams by 65%. In fact, on average, each treatment we installed reduced sediment runoff into streams by nearly 1 ton annually.

American Rivers is working to leverage these early project successes and build a regional effort and robust partnerships behind this work. We’re using our experience in the North Yuba River watershed to build standardized procedures for forest road assessment and prioritization, so we can quickly identify and prioritize problem areas. We’re also working to include this work in large-scale watershed restoration projects to maintain forest access while improving water quality across the Sierra Nevada.

No matter where you live, you’re feeling the impacts of climate change. And chances are, you are feeling the impacts of climate change through your rivers, creeks, and water supplies.

The stakes couldn’t be higher, as dangerous floods threaten communities, drought puts livelihoods at risk and fish and wildlife are pushed closer to extinction as streams dry up.

That is why it is time to put rivers and freshwater at the center of the climate conversation.

The reality and risks of climate change have been emphatically described in recent months by the August 2021 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report and the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26). Human influence has, without a doubt, warmed and changed air quality, ocean health, and land characteristics. The scale of change is unprecedented and human-induced changes are sparking weather and climate extremes in every region of the globe. Much of the focus has been on changes in sea levels, glaciers, forests and the atmosphere.

Climate impacts on rivers, which flow through diverse landscapes, cultures, economies, and habitats, are less discussed but no less important.

Water is life, and rivers are the veins and arteries of the earth. All living things depend on the clean water that rivers provide. Rivers supply much of our drinking water supply. They’re vital to our economy, and our food, transportation and energy systems. Rivers weave through our lives in countless ways that may go unnoticed — until disaster demands our attention. We’ve experienced all the following in the U.S in the past year:

- Disastrous floods putting lives and property at risk

- Drought, aridification and curtailed water supplies threatening farms and ranches, as well as local economies that depend on river recreation

- Wildfires harming downstream water supplies

- Rising temperatures threatening culturally and ecologically important fish species and significant reaches of free-flowing rivers and streams

These impacts most severely affect communities with constrained resources and lack of access to clean and reliable water sources. Black, Indigenous and Latino communities nationwide are disproportionately impacted by river-related climate impacts due to longstanding systemic injustice.

So far, the discussion around rivers and climate has been heard as more of a whisper, where commanding volume is needed – and we are speaking up. In response to COP26, the recent IPCC report, and on-going climate change proposals, we are releasing a Rivers and Climate policy statement outlining six required strategies to strengthen communities in the face of climate change, advance just, equitable solutions that benefit rivers and people, and enhance resilience and adaptation to ongoing changes.

Frontline leaders across the country are tackling many of these issues in their own communities. It is time to come together as a river and clean water movement to ensure decision makers at every level are listening, and making healthy rivers – and all life that depends on them – a top priority.

Last month, two new cracks spread across the face of the political dam that has for decades blocked progress on restoring abundant populations of wild salmon and steelhead to the Inland Northwest.

First, a coalition of fishing and conservation groups including American Rivers joined with the Biden administration, the State of Oregon and the Nez Perce Tribe to ask a federal judge to pause until next summer litigation challenging the latest federal plan for hydropower operations on the lower Snake and lower Columbia rivers. We have committed to work together to develop and implement a comprehensive, long-term solution to benefit endangered salmon and steelhead and that could resolve the long-running litigation over Columbia and Snake River dam operations. The stay, which the judge has granted, will last until July 31, 2022.

Second, Senator Patty Murray (D-WA) announced a “federal-state process on salmon recovery in the Columbia River Basin and the Pacific Northwest” with Washington Governor Jay Inslee to explore how the hydropower, transportation and irrigation benefits of the four lower Snake River dams in eastern Washington can be replaced if they are breached. They committed to deliver their plan by July.

This builds on the momentum that was created last February when Congressman Mike Simpson (R-ID) unveiled a $33.5 billion framework for removing the lower Snake River dams and making investments in clean energy and transportation and irrigation infrastructure to make up for their lost services. Congressman Simpson’s “Columbia Basin Initiative” drew support from Congressman Earl Blumenauer (D-OR) and Oregon Governor Kate Brown.

The announcement by Senator Murray and Governor Inslee drew praise from Samuel Penney, chairman of the Nez Perce Tribal Executive Committee. “The Columbia Power System was literally constructed out of the rivers and reservations and homelands of 19 Columbia Basin tribes,” Penney said. “When that destructive history is truly understood, the modesty of the present request is plain, and the science supporting it is clear: salmon need a free-flowing, climate-resilient Lower Snake River, not a series of slow, easily-warmed reservoirs. The Nez Perce Tribe and its people intend to ensure that salmon do not go extinct on our watch.”

The four lower Snake River dams – Lower Granite, Little Goose, Lower Monumental and Ice Harbor — are driving wild salmon to extinction and harming Native American tribes across the Pacific Northwest. Salmon are the backbone of our region. Without them, our ecosystems and local economies unravel. For tribes, the loss of salmon is an existential crisis, threatening their identity, culture and survival.

The science is clear: removing the four lower Snake dams and restoring a free-flowing lower Snake River must be part of any credible salmon recovery effort. But this is about more than science: it’s about addressing longstanding injustice and healing a river that is a lifeline for tribes and communities across the region.

Time is of the essence. We have eight months to show Northwest leaders and the Biden administration that the restoration of a free-flowing lower Snake River is vital to preventing extinction of salmon runs and to honoring treaties and commitments with tribes.

As Interior Secretary Deb Haaland said, “While it is important to balance the region’s economy and power generation, it is also time to improve conditions for tribes that have relied on these important species since time immemorial.”

We want a healthy river, abundant salmon runs, justice for tribes and a climate-resilient future. It’s time for these dams to come down.

To learn more about the lower Snake River dams, we invite you to reach our Snake River Vision blog series: Climate Resilience, Energy Replacement, Job Security, Tribal Rights, and Vibrant Agriculture.

Sometimes projects don’t go as planned. Sometimes they go sideways really fast. Sometimes those unexpected detours turn out to be a blessing in disguise. This is the story of one such project.

Meet Kehm Run Dam in York, Pennsylvania.

Kehm was a mostly earthen dam with a concrete spillway. Here’s the spillway from the upstream side.

There’s also a smaller weir on the upstream end of the impoundment pictured below.

Kehm sits in the middle of some agricultural fields that are otherwise surrounded by encroaching development. Here’s an aerial view.

It turns out the site is a bit of a diamond in the rough. Like many areas, what was once a rural community in York has filled in with houses and other development. Here, there are still farm fields which makes it a unique place to visit.

Let’s rewind back to 2015— The owners of Kehm Dam receive a letter from PA Department of Environmental Protection’s Dam Safety Program notifying them that their dam is deficient according to state regulations. They must either fix it or remove it. This dam formed a lake used for recreation, but it hasn’t been used as much in recent years as kids have grown up. Here’s a look at the impoundment and a little weekend getaway spot on the lake.

At some point in the past, a family member plugged up the pipe used to drain down the impoundment. It turns out that people need to be able to drain their impoundments these days in case of an emergency, so something had to be done. The owners decided to remove the dam because the cost of repairs would be too much— a conclusion many dam owners come to when faced with the reality of owning aging infrastructure.

American Rivers became involved in the project to help alleviate pressure from the owners who are not otherwise experts on dam removal. For more than 20 years, American Rivers has been working throughout PA to restore healthy river flow and function for the benefit of people and nature. There are more than 3,800 dams throughout the Chesapeake Bay Basin, very few of which provide water supply or flood control benefits. Many of these dams are smaller, older structures that no longer serve a purpose and have potentially become unsafe. This is the case with Kehm Run Dam, the removal of which will benefit resident fish and other aquatic species and reconnect one mile of habitat upstream. This project, like our past work in PA, is intended to provide both ecological and community benefits including improvements to public safety, habitat connectivity, natural ecological function, biodiversity and climate change resilience. Rivers thrive when they’re allowed to move sediment naturally, develop and provide physical habitat for aquatic life, and cycle nutrients in a natural way to support a thriving native ecosystem.

Throughout 2017/2018— We raise funds for what is to become the first phase of the project (thank you to PA Fish and Boat Commission and PA Department of Environmental Protection’s Growing Greener Program).

September 2018— We hire an engineering firm, Princeton Hydro, and navigate through the bumpy road of design and permitting.

Kehm Dam Removal Construction Phase 1

September 2019— Finally, we have permits in hand (a restoration waiver from PA Dam Safety and a drawdown permit from PA Fish and Boat Commission). The project is permitted with a passive sediment release approach for sediment management (this becomes relevant later on). We bid the project for construction. The bids come in. High. Why are they so high? We based our projected costs on an early bid done by one of the owners (no longer living). It turns out that bid did not include removing the whole dam or any of the pipe running through the entire impoundment. We did not realize this ahead of time.

What to do…

Well, we have enough funding to breach the dam, remove the concrete spillway, and remove the upstream weir. Then we will allow the river to find its path and the system to adjust. We can go back after we raise some additional funds to do more work on the site once we see what is truly necessary. Okay, we have a plan.

Here’s what the impoundment looked like before construction from what I will call Point A on the edge of the earthen dam looking upstream.

January 2020— Construction begins. I am 8 months pregnant. This site has some steep hills. I don’t feel as though this picture truly captures how out of breath I was walking up these hills, but it’s all I have.

They started by pumping the water out of the impoundment with a pump machine. The water was pumped from the impoundment into the stream below the dam. Here’s how things were looking from Point A during the pump down.

Next, they removed the concrete spillway with a hydraulic hammer on an excavator. This image shows the breakdown process which happened pretty quickly—only took a few days.

By February, the upstream end of the impoundment was looking more or less as expected. There was a lot of submerged aquatic vegetation up there (hence the lumpiness). At this point, the stream is still flowing into the impoundment, but it doesn’t have a strong path through this vegetation.

Down by the dam, we have some ponding as the pump tries to keep up with moving the water from one side of the dam to the other.

It’s becoming clear that we have a lot of sediment on our hands. This isn’t unexpected for a farm pond. Here’s a look at the impoundment.

PA Department of Environmental Protection thinks there is more sediment here than what was approved under our permit. They order us to stop work on the dam breach before it reaches its final elevation in order to keep sediment from going downstream.

Okaaay. Now what do we do? To sum up the situation:

1) We aren’t allowed to finish breaching the dam.

2) The concrete spillway is already demolished

3) The drawdown pipe is not functional

4) We can’t just electronically pump water out of the impoundment forever

5) You can’t excavate mud soup….we tried…

We had extensive discussions with the engineers and dam safety about how we could temporarily fortify the breach to allow the impoundment time to dry out and stabilize the sediment. In the meantime, Flyway Excavating (the construction contractor) continues to work through on-site problem-solving strategies. They have a breakthrough! They found the end of the pipe that drains the impoundment and have extracted the concrete plug. We can use the pipe to convey the stream from one end of the impoundment to the other without pumping. <Sigh of relief> Here’s the elusive pipe.

We armor the breach with a temporary rock patch to provide protection during storm events, and the river is conveyed through the impoundment pipe. Here’s the near-final temporary breach.

I have my baby a few days later. Yay! (Nothing like last-minute stress!)

Kehm Dam Removal Phase 2

Fast forward to July 2020— I’m back! Baby is doing well! It turns out the site is doing well also. Nature is so resilient. No more “mudflat” in just a few months (with no planting!). Here’s a photo from Point A rotated a bit to include the breach.

We’ve also solved the mystery of the perceived increase in sediment volume in the impoundment. It turns out a math error was made on the design plans for where the bottom elevation should be, making it look like more sediment would evacuate based on the top of sediment elevation. We move on to design Phase 2 of the project to complete the dam breach and remove the upstream weir.

In the meantime, I’ve run out of money. If you’ll remember—we didn’t have enough in-hand to do the full project construction, then we had increased costs with the temporary breach situation.

Enter new best friend Pam Shellenberger with the York County Planning Commission. On a whim, Pam invites Pierre MaCoy with the Susquehanna River Basin Commission (SRBC) for a site visit. Pierre falls in love with the site. Remember—it’s a diamond in the rough of York, PA. Pierre sees the site’s potential. He works with his colleagues at SRBC and they are able to arrange to fund Phase 2 construction. Whew!

We acquire approvals for the Phase 2 plans and we go to construction in September 2021. It’s a time crunch, due to weather and the impacts of manufacturing delays on the construction industry. But we squeak in the site work before the October 1 instream construction restriction deadline.

Here’s a look at Point A before Phase 1 and then after Phase 2.

Here’s a look across the dam before Phase 1 and then after Phase 2.

The dam breach area will fill back in with vegetation over the next growing season and look more like it did between Phases 1 and 2. This photo is from that same spot after Phase 1 (taken August 2021) to give an idea of what will happen.

Future Plans

We’re not done yet! We need to give the site some time to restore itself. The river will cut a path (or possibly even more than one) through the impoundment. We need to wait and see if that causes any erosion concerns. We need to make sure the breach stabilizes for the long term. Things will shift around a bit as this is an active evolving natural system. We are also going to explore the potential to do some active wetland or floodplain restoration. The site may not need it. It may restore full functionality on its own. We shall see.

There is also an active stormwater erosion problem happening through the field adjacent to the impoundment that is causing excessive sediment inputs into the stream. Here is an image of the ditch that the inadequate stormwater management from the road has caused through the field. It has a Pierre in it for scale.

We are hoping to fix that stormwater issue and repair the field as part of Phase 3 of this project. We are also working with local partners to explore the potential of a conservation easement to help keep the surrounding land in agricultural production instead of development.

When PA Dam Safety put a stop to construction in February 2020, I did not immediately know how we would move the project forward. However, thanks to a bit of luck and the engagement of helpful partners, we are making some dam lemonade at this site. I cannot wait to see the results of Phase 3 as we hopefully complete a more holistic restoration of the site for the benefit of people, fish, and wildlife well into the future. Stay tuned!

In September, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service announced that 23 species in total — 11 birds, eight freshwater mussels, two fish, one bat and one plant – were officially extinct and are gone forever. These include, for example, the flat pigtoe, the Southern acornshell, and the yellow-blossom pearly mussel which are three unique species of freshwater mussels that once graced the rivers of the Southeastern U.S.

Some might say accurately that the history of life on Earth has included species going extinct, e.g. the dinosaurs, and that accordingly this is nothing to be worried about. However, a key observation is that the rate of extinction, endangerment, and threat to all species is at unparalleled levels.

Freshwater species are going extinct faster than ocean or land species, and rivers are among the most threatened ecosystems on the planet. Centuries of dams, pollution and degradation have sapped the life from once-vibrant rivers. Consider the fact that only one-third of the world’s rivers remain free-flowing. Combined with severe droughts and floods made more extreme by climate change, rivers face unprecedented threats.

The world is waking up to the crisis of climate change, and the need to stop burning fossil fuels to prevent further warming and climate chaos. But we have yet to give the same level of attention to the biodiversity crisis. Nature’s abundance of plants, insects, birds, fish and other wildlife has immeasurable intrinsic value. It’s also our life support system, supporting the food we eat, the water we drink and the air we breathe.

And rivers are the lifeblood of it all, our planet’s veins and arteries.

Life simply isn’t possible without clean flowing rivers and streams, lush wetlands and floodplains, and healthy watersheds. Rivers are migration routes and connect critical wildlife habitats. Slow-moving back channels serve as nurseries and provide refuges. If imperiled species are to adapt and thrive in a warming world, they will need healthy, connected rivers.

As we work to support fish and wildlife through river protection and restoration, we can’t forget that the biodiversity crisis is connected with two other serious challenges of our time – climate change and environmental injustice. We must listen to the frontline communities and Indigenous leaders who are on bearing the greatest burdens of climate and biodiversity impacts, and who have firsthand knowledge and innovative solutions.

We must always keep our sights on advancing just and equitable solutions for people, rivers and wildlife.

That’s the goal in the Pacific Northwest, where we’re pushing for the removal of the four dams on the lower Snake River to recover the region’s iconic salmon runs – which support more than 130 other species including Southern Resident killer whales, and which are central to the identity, livelihood and cultures of Northwest Tribes. We can address multiple problems at once: we must remove the dams, invest in clean energy alternatives, honor treaties and commitments to tribes, and restore some of the most amazing salmon runs on the planet.

It’s also our goal in the Southeast, where in the face of the removal of freshwater mussels from the endangered species list due to extinction, we are racing to understand the reason freshwater mussel populations are collapsing— entire populations are dying with only small clues as to why. Initial data shows that freshwater mussels may be experiencing their own pandemic and we are partnering with scientists and agencies across the country to examine why mussels are declining so we can advocate for effective solutions to keep them from going extinct.

All across the country, we are dedicated to protecting and restoring all of the life that rivers support. We are grateful to have partners and supporters like you standing with us.

This is a guest blog by Alicia Yodlowsky who is an undergraduate student of environmental studies at North Carolina A&T State University in Greensboro, NC.

The area surrounding the Walnut Creek Wetland Park in Raleigh, North Carolina, has an inspirational history of restoration work. From the 1990s onward, members of the community have worked to transform the once-polluted Walnut Creek, a tributary to the Neuse River, into a nature and wetland education center where children and adults alike can learn about the importance of keeping resources such as wetlands clean. The efforts of the community have continued beyond the original wetland cleanup events: today, work still continues to address pollution and flooding in the neighborhood.

Watershed cleanup efforts began on a small scale: parishioners of St. Ambrose Episcopal Church began to take the garbage out of the wetlands that bordered the church property. As time passed, the efforts grew in scale. Nearby churches began to collaborate in the cleanup efforts, and the Partners for Environmental Justice (PEJ) was formed for the purpose of restoring Walnut Creek and the development of a nature education center in the neighborhood. These combined efforts prevailed; the cleanups restored the wetlands to an ecologically beneficial resource, rather than a landfill. The community began to advocate for a wetland center in order to protect and bring engagement to the site, and by 2009, the Norman and Betty Camp Education Center was established and 58 acres of the wetlands surrounding it were preserved for use as wildlife habitat and to protect the community from further pollution. In 2019, the Center was officially incorporated into the City’s park system providing it with a higher profile and greater resources.

My Time at St. Ambrose

I recently had the experience of attending St. Ambrose Episcopal Church as a parishioner. I had the opportunity to see the rain garden that was installed there in person. The garden, complete with a detailed sign, is well vegetated, with beautiful flowers and lush plants. The rain garden is a major example of the many steps that St. Ambrose and the Southeast Raleigh community have taken to bring both aesthetic and functional green infrastructure and natural resources to the area.

Some small-scale examples of nature-focused work done at St. Ambrose include the many plants that are growing around the outside of the church; these were planted a while after I began attending St. Ambrose. I was able to assist in labeling each of these plants so that parishioners could know what type of plants they were if they were curious. I was also able to assist in renovating the church courtyard; I helped with landscaping, cleaning, and planting in the courtyard. During my time as a parishioner, I had the chance to see for myself the work that had been done by St. Ambrose, as well as the greater Southeast Raleigh community. I had the opportunity both to learn about work that had been done in the past to mitigate flooding and pollution as well as to learn about and see ongoing work throughout the area.

History of Neighborhood and the Creek

The Black community of Southeast Raleigh, including the neighborhoods of Rochester Heights and Biltmore Hills, have historically taken strides to mitigate flooding, address water pollution, create green spaces, and inspire learning and engagement regarding the Walnut Creek Wetlands.

The Walnut Creek wetlands were originally home to a variety of species of wildlife, and the wetlands also had ecological benefits, such as improving the creek’s water quality. The neighborhood of Rochester Heights was built near the wetlands in the mid-20th century, during segregation. Rochester Heights was the first subdivision for Black families in the city; it was also built in a floodplain. After the construction of Rochester Heights, further construction upstream caused water to be channelized and diverted directly and quickly into the creek. As development progressed in the area, the flood control afforded by the natural floodplain wetlands along Walnut Creek began to be overwhelmed. Homes, churches, and other buildings in the nearby community began to flood, and the flooding only worsened as time passed.

The City of Raleigh had also been using the wetlands to dump sewage and other waste in the 20th century. Private companies dumped garbage in the wetlands, and the site practically became a landfill. As the wetlands became strangled by garbage, the nearby predominantly Black community suffered more intense flooding coupled with the added health hazard of polluted floodwater from the dumpsites in the wetlands.

Facing a crisis of property damage, potential health risks, and the destruction of a natural resource, the residents of Rochester Heights took action and initiated the first cleanups without assistance from the City of Raleigh (who had caused part of the problem to begin with). The community started the first push to focus on green infrastructure and to address flooding and pollution. The community reached out to partners, including experts from NC State University, to collaborate and effect change.

Members of the community continued their work to address flooding even after the Walnut Creek Wetland Center was established. The historic disengagement by the City of Raleigh with the initial cleanup of the wetlands or in mitigating flooding in areas like Rochester Heights led to a sense of distrust by the community and they were unwilling to rely on the city for assistance regarding continued flooding. The community formed the Walnut Creek Wetland Community Partnership to focus attention on the watershed and the flooding issues the community was continuing to face. The Partnership is facilitated by the Water Resources Research Institute and College of Natural Resources at NC State University and in 2015 American Rivers was invited to join the effort listening to the partners discuss plans for potential solutions. American Rivers supported a rain garden project as a demonstration of how water could be better managed. Together, the partners built a rain garden at St. Ambrose Episcopal Church that both helped mitigate flooding and pollution and also provided a beautiful new feature adjacent to the church. The project was completed in 2017.

Walnut Creek Restoration Today and Into the Future

The Southeast Raleigh community continues its work on flood mitigation and pollution elimination, and it has gained momentum. The Walnut Creek Wetland Partnership has begun to rebuild the relationship between the community and the City of Raleigh. The City’s stormwater program has prioritized funding for projects that the community has identified as needed improvements to water management in the watershed.

In addition, work is in progress to incorporate land near Bailey Drive into the Walnut Creek Wetland Park. This work has been supported by the Parks with Purpose program of the Conservation Fund. The project aims to create a gateway with green space for community members. An art installation has already been created at the site that describes and celebrates the history of Rochester Heights, Biltmore Hills and the surrounding area. This temporary installation will be remodeled as a permanent installation at the Bailey Drive Gateway after construction is completed.

Also nearby, green stormwater infrastructure will be installed at Biltmore Hills Park. A series of rain gardens will be part of this project which will infiltrate stormwater and filter pollutants. One other project that is in progress with support from Raleigh’s stormwater department is the conversion of Peterson Street to a green street. This project will help mitigate flooding and filter pollutants from the stormwater that gushes down the street.

As someone who has attended St. Ambrose Episcopal Church and has had the chance to be a part of the church community, I feel honored to have witnessed these incredible and inspirational achievements. Working on smaller-scale projects in the church, like the restoration of the courtyard garden, has given me a great appreciation for the advocacy and effort required to achieve larger-scale projects in the community, such as the creation of the Walnut Creek Wetland Park and the Norman and Betty Camp Education Center. The restoration and flood mitigation work that was started by St. Ambrose parishioners in the 1990s has continued forward to this day, and the ongoing efforts have resulted in tangible benefits for the entire Southeast Raleigh community.

This is a guest blog from the Water for Colorado coalition. American Rivers is a founding member of the Water for Colorado Coalition.

Our rivers are the lifeblood of the American West, and we all know that river and water management are both fundamentally important and infinitely complex, governed through a dizzying network of boards and contracts, local entities and statewide groups, individual expertise, and communal understanding.

Known as the “Mother of Rivers,” Colorado’s water impacts everyone and everything. It’s important that Coloradans from across the state have their voices heard as decisions about our critical waterways are made.

It’s especially important to engage right now. The Basin Implementation Plans (BIPs) — locally driven documents identifying goals and actions in each of Colorado’s nine river basins — are undergoing updates and will help inform the update of the state’s Water Plan, due to be final in late 2022. The public comment period for BIPs begins next week and represents a critically important opportunity to learn more, engage in local conversations, and help shape the content of these plans which inform how water is managed at a local level. Before the comment period begins, Water for Colorado has prepared this blog to help you and your community understand the world of river basins and roundtables, and how you can speak up to protect healthy rivers for all who depend on them.

Basins: In order to facilitate conversations around managing our water, Colorado developed nine unique Basins that encompass multiple rivers, natural or artificial boundaries, and watersheds. Each basin has its own governing body called a “basin roundtable” composed of local volunteers who plan and make decisions about how to manage precious water resources.

So why are there nine basins and basin roundtables? The concerns of the Arkansas Basin — from the San Luis Valley to the Eastern Plains, where agriculture reigns supreme — are different from the concerns of the Metro South Platte — where rapid growth and a booming population are key challenges — which are different from the concerns of the Colorado — where the conversations around America’s hardest working river are both intensely local and surprisingly broad. As such, having governing bodies familiar with the unique concerns and opportunities in each basin helps ensure that the management within each basin is driven by locals. This process allows for decisions to be discussed and decided by locals who deeply engage with the rivers that support our environment, economies, and Colorado way of life.

You can check out a map below to determine your river basin; and engage with the graphics at the bottom of this post to learn more about how each basin’s economy is impacted by the recreation in the area.

Basin Roundtable: The basin roundtables were developed by the Colorado Water Conservation Board in 2005 to “facilitate discussions on water management issues and encourage locally driven collaborative solutions” (CWCB Basin Roundtables). These roundtables are composed of local volunteer members who represent a variety of interests including basin agriculture, environment,and recreation. Each basin has its own bank account and funds local projects. Monthly meetings are open to the public, and are where funding and other strategic decisions are made. This means you, and others who care about water conservation can participate and help influence the decision making process. Better yet, you can join these meetings virtually from the comfort of your home.

Basin Implementation Plan: Basin Implementation Plans (BIPs) are developed by basin roundtables to help frame regional issues as part of the overall creation of Colorado’s statewide water plan. While the Colorado Water Plan seeks to address statewide water concerns, BIPs are more focused on local needs, plans, projects, and goals. The BIPs are developed by basin roundtable members with support from the community and ultimately help inform the statewide water plan as well as direct spending priorities for the Roundtables.

Colorado Water Plan: In 2015, then-governor John Hickenlooper ordered the creation of a plan to help coordinate and manage Colorado water. That moment was the impetus for our nine partner organizations to come together to form the Water for Colorado Coalition. The Water Plan was written and developed by the Colorado Water Conservation Board with support from stakeholders, interest groups, and the general public, who submitted 30,000 comments (which Water for Colorado played a major role in gathering) to inform the plan. The core values of the plan are designed to support a productive economy, create efficient water infrastructure, and protect the state’s diverse ecosystems. Colorado’s Water Plan remains a living piece of guidance that undergoes regular updates, the next of which is coming up in June 2022 — and is therefore already underway.

Local engagement: Here’s where you come in!

The first step toward responsibly managing water is working to ensure the public helps shape these plans. Members of the public need to speak up ensuring environmental concerns are addressed in the BIP updates. There’s no one better suited to inform local planning than people like you, who live, work, and recreate in the basins and understand the critical role that water and healthy rivers play in our economy, environment, and everyday lives. In the coming weeks, Water for Colorado will share opportunities for you to engage in the update process for the Basin Implementation Plans during the public comment phase that runs from October 13 through November 15. This is a critical opportunity for you to make your voice heard! Until then, we hope that you share this blog with members of your community to help all Coloradans understand the role they can play in supporting Colorado’s rivers and water!

Sometimes, it’s the little things that remind us how important it is to keep at our work of protecting and restoring rivers.

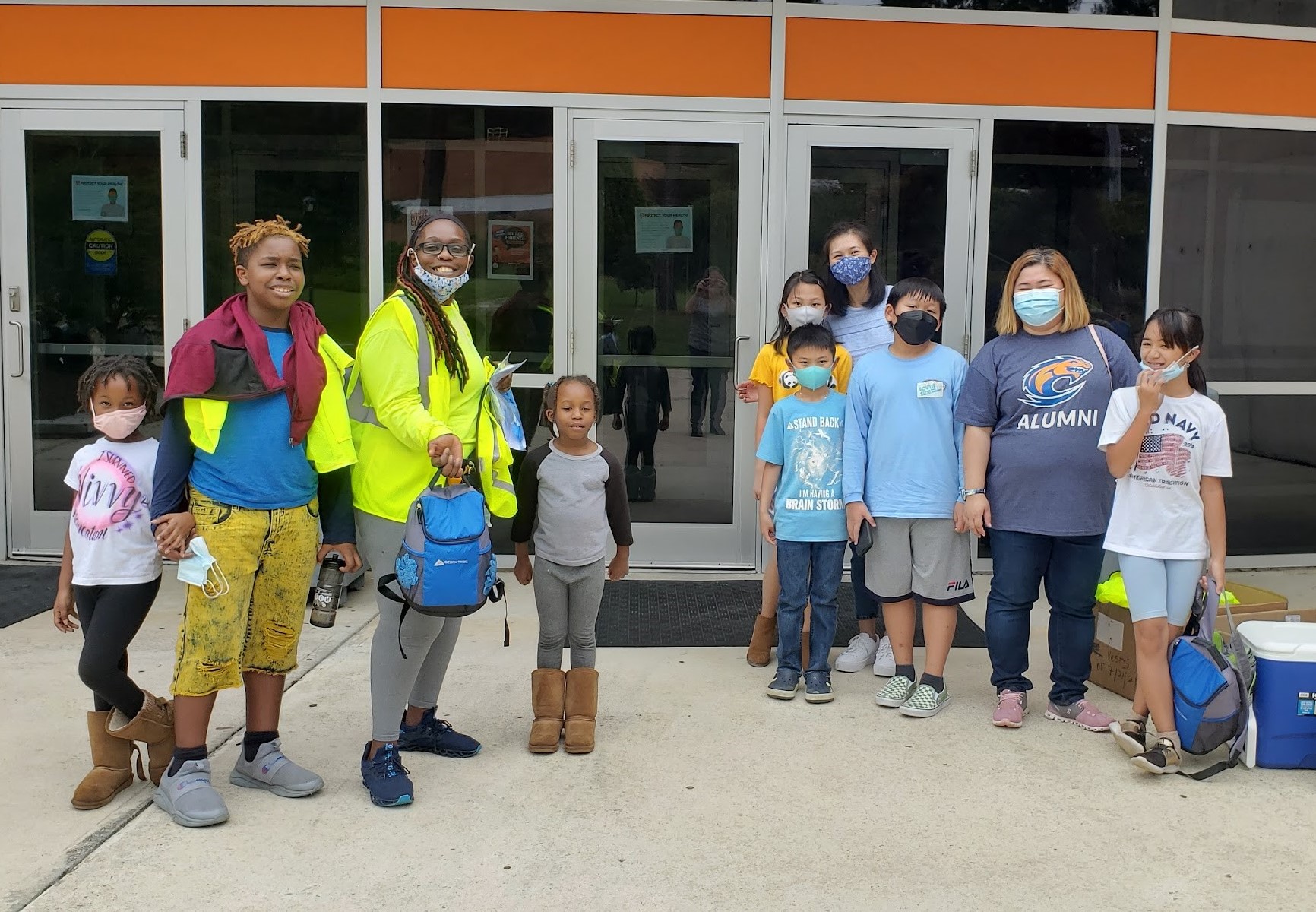

That’s how I felt all afternoon on a Saturday in September of this year, after American Rivers and our partners coordinated the second-ever Southside River Rendezvous, a community-based water quality monitoring event to check up on the health of streams all across Metro Atlanta’s southside.

It was the stories of volunteers returning with their water samples and so much more—sightings of fish, frogs, turtles and hawks, the happy side-effects of a morning of urban creek exploring—it was seeing those intangible benefits of people getting in touch with rivers and river conservation: I think that was what got me reflecting.

And this fall I’ve got a lot to reflect on! As we all learn to adapt to the world’s strange new normals, American Rivers and our partners on the Flint have kept up the pace of conservation and restoration efforts on this hard-working river. Here are some of the exciting things going on:

Restoring the Urban Source of the Flint

Four years after the launch of the Finding the Flint initiative, we’re supporting the city of College Park, Georgia in an effort to build a nature preserve at the urban source of the Flint River. The seven-acre empty parcel where the Flint first sees daylight will not only provide access to nature for a part of Metro Atlanta that’s lacking in nature-based greenspaces, but will also celebrate the source of this regionally important river.

And that’s just one project site. To learn more about the big vision that is Finding the Flint, take a few minutes to watch this new video describing the project. We’re excited to be working with our partners to tell the story of this visionary project—check it out!

And if you need a screen break, remember our We Are Rivers podcast series. There’s a great new episode about Finding the Flint. It features project coordinator Hannah Palmer and her story of working to restore a sense of place and connection to nature in southside Atlanta communities and the Flint River headwaters.

Planning for a Climate-Resilient Future for the River

Meanwhile, American Rivers has kept our focus too on treasured reaches of the Flint River downstream from Atlanta—and on the need to keep the river flowing there, even during drought. This year has been a rainy one, but we’ve continued to work to help the Flint be better prepared and more resilient to the droughts that are sure to return in the future.

Building on our work of many years leading the Upper Flint River Working Group, we are collaborating with water managers and ecologists now to bring critical information on river flows into state water planning efforts. In doing so, we aim to advance efforts to ensure enough clean water for both people and nature in the Flint during drought. And even more than that, this work provides a great opportunity to improve planning and to enhance the climate resilience of the river system and the communities that depend on it, regardless of when drought might return or exactly what conditions a changing climate might throw at us.

Going forward, it’s going to take all this work and more to secure a resilient, healthy future for the river and the communities that depend on it: ensuring that this river connects communities upstream and down, and that it can help those communities prosper, just as their residents and leaders work to ensure its health.

As uncertain as the seasons ahead might be, I can’t wait to see what projects are in the works by the time next fall’s Southside River Rendezvous rolls around.