Guest post from Nancy Schuldt, Water Projects Coordinator for the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa.

This great river runs through what has been the homeland of the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa since before European fur traders first arrived, and before American timber and mining barons set up shop in northeastern Minnesota to exploit the rich resources.

This particular place on the planet provided everything needed for a life of abundance: fish, game, berries, maple sugar, traditional and medicinal plants, birch bark, wood and fiber for canoes and shelters. The river provided a highway for moving to other hunting, fishing and gathering areas, and to connect with other bands and families.

Within the rare freshwater estuary protected from the gales of Lake Superior, Spirit Island lies in the center of Spirit Lake, and is of great cultural significance to the Ojibwe people. It was the location of the Sixth Stopping Place of the great migration westward through the Great Lakes, where the prophecy of reunification was fulfilled, and the “food that grows on the water” (wild rice, or manoomin) was first encountered.

Burial mounds were placed in what is now called Spirit Mountain in Duluth, and in Superior near where the Bong Bridge is now located. (The mounds in Superior, though, were all destroyed and used to fill in the wetlands for development.) As the entire area was considered sacred, encampments were located all around Spirit Island, including Minnesota Point.

In Ojibwe language, Duluth is called “Onigamiinsing” or “At the Little Portage”, as Minnesota Point was a very short and easy portage across rather than going through the river’s mouth. The sands of Minnesota Point are so fragile that the Band’s ancestors used to have to repair portions of the point due to portaging activities. Although allowing the sands to be disturbed from portaging activities would have made the portaging easier over time, leaving such a scar on the land was considered highly disrespectful of the land. After the Fond du Lac Band was removed up river in 1854 to the present-day reservation, and the city of Duluth grew, the scarred portage-way was not repaired and within 20 years, talk of a canal started to emerge.

With its wealth of diverse bird habitats, the Band’s ancestors also used Minnesota Point as a place to gather eggs for food, and the wetlands (much diminished today) provided for migratory waterfowl foraging and staging and another source of food. The estuary was so teeming with wildlife, it allowed for the Band to not only support a large permanent population base at Gete-oodena (“the Old Town”, or the present day City of Superior), but also hundreds of people in the surrounding area. The Band took advantage of its size and location at strategic trade corridors along the St. Louis River up to Knife Portage (now Cloquet), and all along Little Otter Creek to the Moose Horn River, and down Moose Horn River to Kettle River, controlling the other river access, the Nemadji River, from both ends.

Map of the St Louis River

Today, Band members still practice traditional lifeways, in concert with what each season provides.

The river remains the most important fishery resource on the reservation, but those fish now come with a cost— the health risks to humans and wildlife from high mercury concentrations.

A series of hydropower dams downstream of the reservation have permanently altered flows, destroyed wild rice beds and blocked fish passage, and some of the reservoirs remain hotspots of mercury from historic pulp and paper mills.

Overfishing, habitat degradation and pollution wiped out once-abundant lake sturgeon, although the Band is working to reestablish this culturally significant species upstream of the dams. The estuary associated with the St. Louis River is one of 43 Great Lakes Areas of Concern, and the Band is an integral partner in the remediation and restoration work taking place that will one day result in healthier aquatic habitats, renewed stands of wild rice, and fish that will feed the grandchildren to come.

Looking upstream of the reservation, to the headwaters, the Band today raises urgent warnings about the habitat destruction and pollution resulting from a century of hard rock mining. Through the exercise of regulatory authorities for water and air quality, and through treaty rights that guarantee access to hunt, fish and gather healthy resources, the Band is doing all it can to prevent further damage to the lands and waters that sustain us all.

Ricing on the river

Along with other tribes and first nations, the Fond du Lac Band’s spiritual and cultural connections to Mother Earth are evident in the willingness to embrace the responsibility of protecting and preserving the land and waters.

Water, or nibi, is the lifeblood of Mother Earth, and women are regarded as the protectors of the water.

As stated in the Tribal and First Nations Great Lakes Water Accord (2004), signed by leaders from Fond du Lac and 37 other Great Lakes tribes and first nations:

When considering matters of great importance we are taught to think beyond the current generation. We are also taught that each of us is someone’s seventh generation. We must continually ask ourselves what we are leaving for a future seventh generation.

Nancy Schuldt is the Water Projects Coordinator for the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa. The Fond du Lac Band is one of six Chippewa Indian Bands in Minnesota. Archaeologists maintain that ancestors of the present day Chippewa (Ojibwe) have resided in the Great Lakes area since 800 A.D.

Two weeks ago, I had the opportunity to travel down the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon with as diverse a group of people as you’re likely to meet. Included in the mix were a cattle rancher, an anthropologist, a jeweler, a Hollywood producer, a former U.S. Senator, a community organizer, a former firefighter, a Vietnam veteran, a biotech millionaire, a retired police officer, and a smattering of tree-hugging environmentalists like myself.

What brought us together was more than scenic marvels, campfire songs, and white-knuckle descents of the Canyon’s many rapids, although the trip was all of that. We were there to take a journey through time as well as space, visiting the Canyon’s geologic and cultural past and pondering its uncertain future.

A trip through the Grand Canyon is a thrill ride for geology buffs. Some of the oldest rock on the surface of the earth – up to 2 billion years old – can be found there. The clash of tectonic plates, the layering and twisting of volcanic and sedimentary rock, the rise and recession of new mountains and ancient oceans over geologic time have written the history of our planet on the canyon walls. The latest chapter of that history is still being drafted as the sediment and erosive power of the Colorado River continues to sculpt and shape the canyon floor.

While the geologic history of the Canyon is on gigantic display all around you, its equally compelling cultural history is less conspicuous. You have to know exactly where to look. You have to listen very closely. Most importantly, you have to have the right guides. And that’s what made this particular trip to the Canyon so special.

The ex-cop on the trip was Merv Yoyetawa, a Hopi tribal leader; the jeweler was Octavius Seowtawa, a cultural leader of the A:shiwi (Zuni) people; the former firefighter was Bennett Jackson, a Hualapai now with the tribe’s Department of Cultural Resources; the Vietnam vet was Barney “Rocky” Imus, a Hualapai tribal elder; and the rancher and community organizer were Earlene Reid and Sarana Riggs, Navajo women and founding members of Save the Confluence, a group of activists fighting to preserve an important piece of the Canyon’s cultural tradition.

Together, these native leaders, representing four of the eleven tribes of the region, guided us to important and sacred sites, allowed us to watch and sometimes participate in their ceremonies of respect and reverence, and shared with us the histories of their peoples and their deep spiritual connections to the Colorado River and the Grand Canyon.

The histories of the Hopi, A:shiwi, Hualupai, and Navajo peoples begin in and around the Grand Canyon. The A:shiwi, for example, emerged into this world (from a previous one, a long story) near what we now call Ribbon Falls. Their first glimpses of the new world, the heart of the Grand Canyon, still feature in their stories, songs, and religious ceremonies. Shortly after they emerged, the A:shiwi began their quest for the “middle place,” where they were destined to settle.

Their travels took them up the Little Colorado River and to the headwaters of its tributary the Zuni River in New Mexico, where they have lived ever since. The other tribes of the region have similar stories, though each has its unique cultural and historical elements. In addition to its importance as the place of emergence, the Canyon has served the tribes at various times as a refuge from attack, a hiding place for goods, a provider of life-giving salt, and a source of food in times of scarcity. The natives of the region revere the Canyon, and make little distinction between the living and their surroundings. The Grand Canyon’s rivers and rock walls, seeps and springs are as alive as any person.

One such sacred place is the confluence of the Little Colorado and Colorado rivers, a locale of spectacular isolation. Standing on the banks of the muddy Little Colorado just above the confluence, I listened with the group as Sarana told the story of when Changing Woman, the creator of the Navajo people, passed this way on her way to and from the ocean. Merv told us that not far up the river from the spot where we stood, the Hopi emerged into this world and took up their sacred duty to ensure that the rains fall and the springs flow with life-giving water. Just downriver is where developers are pushing a proposal for a tram – the Escalade project – that would transport up to 10,000 tourists a day to sight-see, dine, and shop.

An ancient Grand Canyon petroglyph

It’s the Escalade that brought this group together in the first place. The project is opposed by environmental groups as an affront to the scenic beauty and natural grandeur that make the Grand Canyon a national, indeed a global, treasure. Though it enjoys some support among the Navajo, many, like Sarana and Earline, see it as an assault on their spiritual beliefs and their traditional way of life.

It is opposed by native leaders of the Hopi, A:shiwi, Hualupai and other Grand Canyon tribes that don’t always unite in common purpose.

As we traveled together by raft and oar boat for seven days, six nights and 87 miles down the Colorado in the upper Grand Canyon, the conversation ranged beyond Escalade to include the many other threats to the beauty, sanctity, and ecological health of the Canyon: potentially unfettered development in gateway communities, new mining and the dangers posed by old, polluted mine sites, excessive demand on groundwater and its potential impact on the Canyon’s vital springs, and the health of the Colorado River itself. We also shared meals, swapped stories, sang songs, and tossed around pop cultural references – at various times, I found myself explaining the mythology of “Transformers” to a former US Senator, exchanging views on the merits of diet soda with a Hualapai tribal official, and discussing with a Hopi Tribal Council member whether Tony Romo will ever win a Super Bowl (we disagreed).

In other words, the Canyon had, as one participant put it, “worked its magic.” We had arrived as strangers, and our shared adventure in the Canyon had forged us into a group of friends with a common purpose: to build upon what we had learned about the issues and about each other, to pool our talents, knowledge, and resources to save the Grand Canyon.

Perhaps the most important thing I learned on the trip was the power of story in the Grand Canyon. I’ve told many people the story of the Canyon from the perspective of an “Anglo” conservationist: It is a place of truly unique natural grandeur and a national treasure, and the Escalade and other development schemes threaten to destroy the very attributes that make the Canyon so special. The Native people tell a different story, one of history and culture and great spiritual power. They tell of how their history begins in the Grand Canyon, and how it remains, for them, the center of the world.

The stories are complementary, and are symbolic of how national, regional, and tribal groups can work together to secure the future of the Grand Canyon. It’s a future that I have a greater stake in than I once thought. As Merv explained it, it wasn’t just the Hopi that emerged at Sisapuni on the Little Colorado. It was all people, and the spirits of all people will eventually return. As he looked around the circle at all of us, with all our diverse backgrounds, he smiled and said, “We are all from here.”

Guest post by Andrew Slade, Minnesota Environmental Partnership.

From a canoe, Seven Beaver Lake and Lake Superior could hardly feel more different. Seven Beaver is shallow and muddy, nothing like the deep and rocky Superior. Yet they are deeply connected. Paddling Seven Beaver Lake a few weeks ago, we were at the headwaters of the St. Louis River.

If you care about Lake Superior, you should care about the St. Louis River.

It’s not only the largest of all the Minnesota tributaries to Lake Superior, it’s actually the largest on the entire U.S. side of this transboundary lake. What happens in the St. Louis River can and will impact Minnesota’s one and only Great Lake.

Now the St. Louis River, and consequently Lake Superior, are threatened by new sulfide mining led by PolyMet Mining Corporation. That’s why the St. Louis River has been recognized by American Rivers as one of America’s Most Endangered Rivers® of 2015.

From the rice-lined shores of Seven Beaver Lake, the St. Louis River winds 195 miles across northeastern Minnesota. The water gurgling through the beaver dams on this lake looks clear and clean. Over many thousands of years, the St. Louis River has delivered to Lake Superior countless tons of material eroded from its watershed. The sediment in the estuary, where a few stands of wild rice still grow, came from the river. Walleye and sturgeon in the big lake were born and grew up in the river.

And, for about 100 years, the St. Louis River has carried tons of contaminants from human activities.

Wild rice is abundant in the headwaters of the St. Louis River, but disappears downstream of the mining district due to sulfide discharges.

To this day, there are high levels of PCBs and mercury in the St. Louis River. Not here in the wild headwaters, but below the historic lumber mill town of Cloquet.

As of 2007, the river had high levels for a veritable cocktail of industrial contaminants, including DDT, dioxin, mercury, and PCBs. How much of that historic water pollution actually entered Lake Superior is hard to determine now, but we know that these types of contaminants build up in the food chain and get into our bodies. In 2012, research revealed that one in ten infants in the North Shore area had high levels of mercury in their blood.

Just as we’re making progress on reducing the sources of these contaminants, along comes a proposal for a new source of mercury and sulfates in the river: the PolyMet copper-nickel sulfide mine. PolyMet hopes to open Minnesota’s first sulfide mine sometime in 2017, and may be seeking permits as soon as this fall.

Seven Beaver Lake, deep in the Superior National Forest, is the headwaters of the endangered St. Louis River. The proposed PolyMet mine pit is eleven miles from here in the same wetland complex.

How could the State of Minnesota ever allow the construction of a new mine and a new source of mercury in the St. Louis River?

The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency is saying there is too much mercury in the river and its fish; at the same time, they are being asked to allow more mercury to be added.

There are so many reasons to protect the endangered St. Louis River from the threats proposed by the PolyMet project. Here’s one very important reason— to save Lake Superior and protect the drinking water supply for thousands of Americans.

Andrew Slade is the Northeast Program Coordinator for Minnesota Environmental Partnership. Minnesota Environmental Partnership is a statewide coalition of environmental and conservation nonprofits working together for clean energy, clean water, and investments in Minnesota’s Great Outdoors.

The National Hunting & Fishing Day has its origins in connecting hunting and fishing with conservation, both to recognize that hunters and anglers were some of the first and most ardent people committed to restoring fish and wildlife and to encourage the continued effort to protect fish, wildlife, and the habitats they depend upon.

The work that American Rivers does makes a direct contribution to this cause. Whether we are removing dams, protecting rivers and their adjacent lands through “Wild and Scenic” designations, restoring floodplains and meadows, or working with hydropower companies to improve their dam operations for the benefit of the river downstream, virtually all of our work helps fish habitat and fishing. Here is a little more detail, and you can read more examples here:

Dam removals: there is no single, better thing you can do to restore a river than to remove an outdated dam. Whether it’s to open up spawning grounds and seasonal migrations for trout (like the 6 miles of the Batten Kill opened by removing the Dufresne Dam in Manchester, Vermont…a nice side trip if you are in town either visiting Orvis or stopping by the American Museum of Fly Fishing), removing barriers for salmon (like on the Penobscot for Atlantic salmon or the Elwha for Pacific salmon and steelhead), or helping to recover/restore populations of herring and other forage fish that stripers, false albacore, and other predator fish depend upon, there’s a great benefit for fish and fishing.

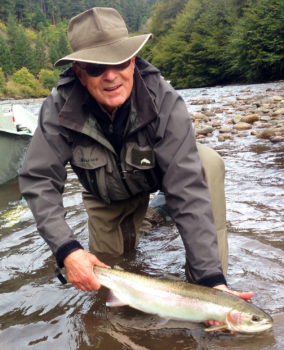

Bob McDermott fishing

Wild and Scenic River designations: by working with local, state, and federal representatives to designate a river as “Wild and Scenic”, a river is protected forever from damming, diversions, or any development that hurts its natural value. A great example is the 415 miles of the Snake River and its tributaries around Jackson Hole, which American Rivers played a key role in supporting and which is now essentially a native trout sanctuary.

Floodplain and meadow restorations: salmon that rear in a floodplain are twice as big when they go to sea and twice as likely to return to spawn. Meadow restorations, like Pine Creek in California, allow for full-year migrations that connect native trout to their spawning grounds.

Hydropower improvements: by working with hydropower companies to establish minimum flows and minimum levels of dissolved oxygen, we can bring rivers back to life. This was the case on the Saluda River in South Carolina, where trout survive year-round and you can now catch 24-inch brown trout.

You can learn more about our work that protects and restores fish habitat by going to www.AmericanRivers.org/AnglersFund, and clicking on the conservation updates we’ve posted over the past few year.

Thanks for your interest in our work, and happy fishing on National Hunting and Fishing Day.

The General Mining Act of 1872 is an antiquated law that governs mining industry operations on public lands, despite advances in knowledge and technology that should long ago have led to a change in the way mines are opened and operated. A lot has changed since this law was passed 143 years ago. In that time, countless discoveries and advancements have kept our country in the forefront of technological advancement, increasing our awareness of the impacts of mining on the environment.

So you might be pondering… what was happening around 1872? Has America really changed that much? The answer is simple: Yes.

Let’s think about the everyday life of an American citizen. If you were born in 1872, like President Calvin Coolidge, you were likely to die by the age of 40. At this time, sanitation had only recently been implemented to prevent the spread of germs. This means that many doctors wouldn’t bother to wash their hands between patients because they considered infection to be spontaneous.

President Ulysses S. Grant must have really wanted those lucky enough to survive a visit to the doctor to move out west because the Federal Government at the time would only charge a maximum of $5 per acre for minerals extracted from publically-owned lands. (It’s worth noting that many of these “publically-owned lands” had recently been taken at gunpoint from Native Americans who had lived on them for millennia.) Perhaps President Grant thought that pioneers needed additional coaxing. After all, no one could hop in their cars and relocate. Henry Ford, being nine years old, was still 36 years away from developing his Model T.

Another jaw-dropping contrast between now and then is how far our technology has come. The original typewriter was produced one year after this enduring mining law that dictates how economic minerals, such as gold, copper and uranium, are mined on federal property. Just like our communication capacity, our capabilities and efficiency for mineral extraction have come a long way from the pickaxe and pan.

I do not wish to undermine the individuals that shaped our great nation. I mean only to showcase that nearly every aspect from medicine and science to transportation and communication has been updated to reflect our constantly changing landscape. In the meantime, a major law governing mining has remained unchanged and outdated, even as the technology associated with mining operations has changed dramatically.

If our forefathers had known that foreign-owned mining companies could take valuable hardrock minerals including gold, uranium and nickel from public lands without royalty payment to the taxpayer, they might have structured this law differently. They most likely trusted that Americans wouldn’t stand for such a thing. I expect that they assumed we would fix the law if a problem arose, adapting to the changing times. I hope that they would encourage us to protect our lands from the permanent harm we’ve seen done time and time again from large-scale industrial mining.

The 1872 mining law needs be updated, and but it’s a big battle against well entrenched powerful special interests. It’s a fight we welcome, but it’s not going to be won overnight.

In the meantime, we can use the tools we have to protect our public lands today. Southwestern Oregon is threatened by industrial strip mining and it would be a shame to ruin these lands and essentially take them off the map.

In this day and age, it doesn’t seem possible that a foreign mining corporation could come to America, take over a vast swath of Oregon wilderness, rip out an entire forest, turn a mountain ridge into an enormous open-pit strip-mine, pollute some of our nation’s last, freely flowing pristine rivers, and destroy untold numbers of cutthroat trout, steelhead and salmon, then leave a hugely expensive mess for taxpayers to clean up once the mine plays out.

But that’s exactly what’s about to happen— if we fail to stop it.

California’s Smith River is known for its incredible water quality, clarity, and pure strains of wild salmon and steelhead.

The Smith River begins its life in the mountains of Oregon and twists and turns through the southwestern part of the state before flowing into northwestern California where it provides the drinking water for not only myself, but also the approximately 30,000 year-around residents, and the thousands of seasonal tourists who visit this remote county in which I live—Del Norte—the north-westernmost county in California, 350 miles north of San Francisco.

The Smith is one of the most beautiful rivers you’ll ever see. After it enters California, it meanders through the towering, ancient, cathedral-like groves of Redwoods National and State Parks. It cuts through deep gorges and canyons, and roars over rocky chutes. When it’s swollen by winter storms and snow-melt, it produces world-class whitewater for rafters and kayakers. The bedrock that forms its various channels is a type of green-tinted serpentine that makes the river’s crystal-clear water appear to be a flawless, transparent, other-worldly emerald hue.

Because it flows through the redwoods and always moves swiftly due to continuous drops in elevation as it rushes from the mountains to the sea, unhindered by dams, there’s almost no runoff or sediment to make it cloudy or to settle on its rocky bed. It’s so clear, you can easily see rocks and gravel on the bottom, even in the deepest holes. In late summer, when the current slows and water levels drop, you can watch trout, steelhead and salmon swim leisurely by. Eventually, the offspring of those salmon and steelhead will return to the sea where they’ll play an important yet declining role in Del Norte County’s commercial and sport-fishing industries.

Del Norte is one of California’s poorest counties. It needs all the economic help it can get, and certainly does not need a mining corporation poisoning the streams that provide an already-diminishing supply of fish to its struggling fishing industry. Besides, the beauty and recreational value of the Smith River wending its way through the redwoods draws visitors from all over the world, and when they stay in our local lodgings and eat in our local restaurants, their drinking water comes from the Smith River. It’s not just local residents who’ll be drinking arsenic-laced tap water if nickel mining is permitted in southwestern Oregon. And tourists can decide to vacation elsewhere, further eroding our already precarious local economy.

What You Can Do

We must put a stop to this outrageous despoiling of our last, best, wild places. Please lend your support to the fight to save our undammed, pristine rivers.

Take a photo tour of Pistol River, Hunter Creek and the Smith Rivers from the eye of Ken Morrish, photographer and co-owner of Fly Water Travel in Ashland, Oregon.

[metaslider id=25967]

What You Can Do

This action to protect the Rogue, Illinois and Smith rivers in Oregon and California has been closed.

This post was originally discussing Senate bill S 1236. Currently the House Committee on Energy & Commerce voted to add an amendment to the energy bill [HR 8] that accomplishes the same goals with the same problems.

A bill pending in the U.S. Senate would give the hydroelectric industry and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission the kind of unconditional authority more akin to what the Robber Barons enjoyed in the late 1800s, than to what reasonable people might expect today.

Consider the last time a plan like Senate Bill 1236 was hatched. It was 2005. If anyone wonders how, during the last decade, a million new gas wells got drilled while people’s water supplies were fouled, streams depleted, sewage plants overloaded and air polluted, look no further than the “Halliburton loophole” — a Dick-Cheney-greased act of Congress. That Bush-era law exempted the gas industry from regulations that otherwise apply to the injection of undisclosed toxins into groundwater.

Now, with Congress leaning in its favor, the hydropower industry wants to ensure its share of fracking-style freedom. Proposed by Alaska Republican Sen. Lisa Murkowski, the so-called Hydropower Improvement Act of 2015 would exempt the industry from long-standing laws that protect rivers and streams from pollution.

Under the guise of promoting renewable energy, the bill would eliminate the ability of fish and wildlife agencies to require compromises when those public resources are imperiled. It would restrict the authority of the Environmental Protection Agency and the states to uphold accepted standards for pollution, temperature, and flow under the Clean Water Act and other statutes, and make sure that they are not violated. The bill would limit citizen involvement and appeals when members of the public, including local governments and Indian tribes, are concerned about their rivers, jobs and communities. It would dispose of due process in investigation, review and negotiation, giving sole authority to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, whose mission, political culture and history is unabashedly to increase hydropower production.

Because this measure slashes virtually all ties of hydro-proposals to environmental regulations, it makes you wonder about its sponsors’ boast that they are ensuring “clean” energy. If this bill is so great for the environment, why does it eliminate environmental reviews?

Clean energy sounds good, and some hydropower plans pose little conflict with other public values. But many other hydroelectric proposals come with sticky strings attached. Dams that are built for hydroelectric production flood canyons, valleys, forests, rivers and homes. The diversions to generators dry up rivers needed by fish, including our legendary salmon in California and the Northwest. Power production alters the schedule of flows, so that floods get released during one hour but are turned into trickles during the next, leaving fish either flushed out or high-and-dry. Hydropower development can also warm rivers at a time when temperature pollution is one of the most pressing problems for surviving fisheries and endangered species.

This unnecessary act of Congress would abandon a time-tested process of cooperation and negotiation that for decades has led to better hydroelectric production. For example, on the North Fork Feather River in California — otherwise an exquisite stream of the Sierra Nevada — hydroelectric plants for years dried up channels and flushed flows so erratically that they endangered the lives of anglers. After all sides recognized their responsibilities and the need to compromise, the flows were revised to produce power while sustaining other uses of the river. The Feather has since become a recreational hotspot that fuels the local economy.

On the Deschutes River of Oregon, salmon and steelhead that had been unable to reach their spawning grounds since 1958 (despite official state objection) are on their way again, thanks to an agreement between the power producer, Indian tribes and resource agencies. Everyone will benefit.

At the Yuba River in California, the Chelan in Washington, the Bear in Idaho, and dozens of others throughout the country, agreements have been peacefully and economically negotiated. These better outcomes include laws like the Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act that gave citizens and public agencies some say in the fate of our public waterways.

The Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, representing agencies in all 50 states, opposes this measure — deceptively called “hydropower regulatory modernization” — as a giant step backward. Our laws governing hydropower are working well. Legitimate power producers are doing a good job. We don’t need to pander to those who aspire to become Robber Barons in our own time.

What you can do

Help stop this dirty energy bill from happening. Tell Congress to oppose this hydropower bill that would let dams be operated without the safeguards of modern environmental laws. »

Leaving no stone unturned, or more accurately no significant stormwater source uncontrolled, American Rivers, the Natural Resources Defense Council and Clean Air Council petitioned the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to ensure control of significant sources of pollution that contribute to costly local clean-up efforts and are not already adequately addressed by urban stormwater programs.

In the Delaware River basin, stormwater runoff is the most common clean water problem—storms wash nutrients from exposed soils, erode streambanks, and carry pollutants of off hard surfaces such as rooftops and roadways. There is a strong correlation between these impervious or hard surfaces and degraded water quality in our streams.

Where there are large areas of imperviousness, cities bear the cost of treating drinking water and cleaning streams that flow to downstream communities. Yet cities do not have the ability to control some of the most significant polluted stormwater runoff at its source when it is generated on private property. Controlling polluted stormwater runoff on the site of private commercial, industrial and institutional facilities with large areas of impervious surface will greatly reduce pollution in streams and the burden of clean up for localities.

Take a look at the small watershed of Army Creek in New Castle County, Delaware, just south of the city of Wilmington. The watershed is less than 8,000 acres and flows directly into the Delaware River. It serves an urban residential population and much commercial and industrial activity. This creek, as its name implies, is a workhorse. Notable clean ups of pollutants such as dioxin and PCBs from past activities have already occurred to help this creek continue its service and maintain healthy flows to support the diverse Delaware River estuary habitat. But, Army Creek is also on the state’s list of impaired waterways because of excess nutrients or nitrogen and phosphorus pollution. Nearly 32% of the watershed’s land area is commercial, industrial or institutional and 80% of that land use is within half a mile of Army Creek. Models estimate that, out of all urban stormwater sources, these land uses in Army Creek’s watershed contribute 34% of total phosphorus pollution and 39% of total nitrogen pollution. The large swaths of hard, impervious surfaces associated with these commercial, industrial and institutional land uses likely contribute four times the nutrient pollution loads that Army Creek watershed would receive under natural land cover from the entire watershed.

In the Army Creek watershed, in watersheds throughout EPA Region 3 and across the nation, these significant contributors of polluted stormwater runoff to impaired waterways represent a gap in stormwater management programs and a costly clean-up burden to localities receiving polluted runoff to their stormwater infrastructure system. These polluting sources fall outside of existing controls such as 1) Delaware’s urban stormwater permit (or MS4) for which New Castle County is the permit holder and permit requirements are limited to permit holder controlled land, 2) management practice requirements for control of runoff at new development or redevelopment sites that do not apply to existing development and 3) control of typical point source pollutants such as the PCBs and dioxins or those treated as wastewater and then discharged directly into the Delaware River. Fortunately, EPA can help…

The Clean Water Act has a provision called residual designation authority (RDA). If EPA determines that a sector or category of stormwater discharge sources are contributing to water quality violations, the agency must exercise its authority—RDA– and require those polluters to have permits which will direct steps toward pollution reduction.

We have petitioned EPA to use RDA to require contributors of stormwater runoff to work under a permit to manage their stormwater and ensure Army Creek can deliver clean water to the Delaware River. Since green infrastructure practices such as green roofs, rain gardens and porous pavement offer sustainable and cost-effective ways manage stormwater from large areas of imperviousness, RDA can also drive benefits within Army Creek such as safer communities, cleaner air, flood damage reductions and more attractive industrial, commercial and institutional sites. Saleem Chapman, Director of Policy and Strategy at Clean Air Council says “experience developing green infrastructure solutions in Delaware demonstrates the advantages of these types of clean water projects to overall local community health.”

Our petitions ask EPA to use RDA so significant sources of stormwater pollution will no longer be unpermitted, uncontrolled, burdening localities and impairing waterways. RDA can help reduce polluted stormwater reaching Army Creek within New Castle County and other urban watersheds and communities throughout EPA Region 3.

Learn More

- Read the Army Creek petition for EPA Region 3 to exercise RDA [PDF]

- Read the petition for Back Creek within the Chesapeake Bay [PDF]

- Read about petitions in EPA Region 9, California

Guest post by Eric Davis

From childhood to adulthood and through the lens of my chosen profession, I have always viewed waterways as an indispensable outlet for recreational pursuits for all ages and ability levels. In the South Carolina Lowcountry water is everywhere. However, in the suburban population centers around Summerville and North Charleston in Dorchester County, the Ashley River represents the only public waterway suitable for a wide variety of water based activities.

As a fairly new resident and employee of Dorchester County, I am learning how extremely fortunate we are to host a portion of the Ashley River within our borders as it snakes from headwaters in Cypress Swamp toward ever-widening salt marshes and onward to Charleston Harbor. My daughter Mariella has taken her first paddle strokes in this waterway, helping Daddy get a feel for all this lazy Lowcountry tidal river has to offer.

Ashley River Blue Trail, SC

The Ashley River is located in one of the most rapidly growing regions in the United States. Because of this, it is even more imperative that we work now to promote and preserve the Ashley River as an easily accessible recreational oasis for a multitude of activities that do so much to benefit us economically, physically, mentally, and spiritually.

Toward this end, plans for developing riverfront parkland, access points, special events, and programming that showcase the recreational value of the Ashley River figure prominently into Dorchester County’s current effort to create its first ever park system.

The fact that American Rivers has taken the lead in creating the Ashley River Blue Trail dovetails seamlessly with Dorchester County’s plans. A Blue Trail is a river adopted by a local community that is dedicated to improving family-friendly recreation such as fishing, boating, and wildlife-watching, and conserving riverside land. Just as hiking trails are designed to help people explore the land, Blue Trails help people discover their rivers. They help communities improve recreation and tourism, benefit local businesses and the economy, and protect river health and wildlife. They are voluntary, cooperative, locally led efforts that improve community quality of life. As a nationwide leader in blue trail development, American Rivers has supported Dorchester County’s objectives for the Ashley with expertise, technical assistance, and community organizing.

The author and Mariella on a paddle

A major milestone in the Ashley River Blue Trail project is the release of the associated map. Through American Rivers’ leadership, a coalition of public and private entities pulled together to design and fund the Ashley River Blue Trail Map.

This map is a positive step in encouraging enhanced utilization and stewardship of this outstanding recreational resource. It is Dorchester County’s hope that the map must be updated frequently as additional blue trail infrastructure comes to fruition!

Look for information about obtaining waterproof hardcopies of the map in the coming months. Until then, Mariella and I will see you on the river!

Raleigh is plotting an innovative and thoughtful path toward resurrecting its forgotten streams and beginning to heal the Neuse River.

Like many other highly urbanized cities, Raleigh was built at a time when there was little understanding of the impacts that poorly treated stormwater would have on the health of local streams. As a result, its streams currently suffer from the ill effects of “urban stream syndrome,” which encompasses wildly variable flows, very limited wildlife habitat, and terrible water quality. Anyone who has passed one of the area’s trash-strewn creeks or visited a nearly dry stream bed has likely observed this phenomenon.

Unfortunately, this damage reaches beyond the shores of Raleigh’s streams. One of North Carolina’s most iconic rivers, the Neuse, is fed by all these damaged waterways. Communities along the length of the river rely on its clean water for agriculture and maritime commerce. To reduce its impact on its local rivers and streams, Raleigh developed and has begun to implement a green infrastructure plan.

The City Council unanimously adopted the plan this spring, after stakeholders spent more than two years working to find new ways for the city to address its infrastructure problems. Now, project planners must consider how water will interact with their buildings, roads, or parks. The city will also invest in green infrastructure, such as rain gardens, cisterns, and green streets, on city-owned property. Additionally, city officials will work with private landowners to retrofit their property or install new green infrastructure.

The plan was the result of a long collaboration process that built trust and commitment among diverse stakeholders.

It will take decades to fully implement the plan, but stakeholders can expect the presence of green infrastructure projects to increase exponentially over that time.

At the end of this process, Raleigh residents can expect that the streams and creeks that trickle through their city will be cured of “urban stream syndrome.” Instead, they will become attractions for area families, urban oases for wildlife, and natural sources of clean water for the Neuse.

Do you have a river, stream, lake or beach that’s near and dear to your heart? So do many people – and unfortunately, when people visit rivers en masse, things often get left behind.

Fortunately, it’s easy to get involved and clean up the rivers that matter to you. American Rivers helps set up cleanups around the country throughout the year with our National River Cleanup campaign. Don’t see a cleanup on your river? Don’t worry, you can start one with support and cleanup supplies from us!

A clean swimming hole on the South Yuba River

Here in California, we’re partnering with Friends of Marsh Creek to host a big cleanup in Contra Costa County on September 19, during Coastal Cleanup Day. Hundreds of cleanups are happening that day throughout the state, and you can find another coastal cleanup (and some inland ones) near you here.

What if you live in the mountains, far from the ocean? September 19 is also the Great Sierra River Cleanup, where dozens of groups throughout the Sierra host cleanups. You can find a sierra cleanup here.

So get out there, find a river you love, and show it how you feel with a cleanup. If you’re in California, join thousands of other river lovers on September 19!