Spring has sprung on the Waccamaw River Blue Trail with birds nesting, flowers blooming, and breezes blowing keeping temperatures comfortable as the sun warms your face. Visitors began pouring in to the Grand Strand last month with spring breakers looking for a little relaxation.

While many are drawn to our beautiful ocean and beaches, if you turn around you find a luscious backyard river flowing.

Peaceful blackwaters, the color of tea during sunny days due to the tannins that leach into the water as leaves and vegetation decays, tempt locals and visitors to hop in to kayaks and canoes to explore the unique. “As a result of the Waccamaw River Blue Trail, opportunities for river recreation have improved [because of] an increase in the number of outfitters operating on the Waccamaw and an increase in interest in kayaking, canoeing and paddleboarding on the Waccamaw,” Ellis said. “The Waccamaw River Blue Trail has also served to focus efforts for land conservation along its length in both North and South Carolina.”

Wildlife abounds with exciting opportunities to see swallow-tailed kites, blue herons, osprey, and many others. The trees are now covered in green and flowers are blooming, the great cypresses providing impressive scenery and shade along the river front. There are many outfitters along the Waccamaw River Blue Trail, including: Black River Outdoors, Gator Bait Adventure Tours, Great Escapes Kayak Expeditions (used by an author who recently came to explore the Waccamaw), Surf the Earth, and Waccamaw Canoe and Kayak.

To learn more about planning your own adventure on the Waccamaw River Blue Trail, visit the website.

On Wednesday, April 6th, American Rivers will join many other Klamath stakeholders at the mouth of the Klamath River on the Yurok Reservation in Requa California to sign two settlement agreements that will put the most significant dam removal and river restoration project the United States has seen back on track for completion in 2020.

Signatories will include U.S. Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell, California Governor Edmond Brown Jr., Oregon Governor Kate Brown, PacifiCorp President and CEO, the Yurok Tribal Chairman Thomas O’Rourke, Karuk Tribe Chairman Russell Attebery, other NGOs, farmers and commercial fishermen.

American Rivers and our partners have been working since 2000 to remove PacifiCorp’s four obsolete dams on the Klamath River, which have blocked salmon and steelhead from reaching more than 300 miles of historic habitat for nearly 100 years, and cause toxic algae blooms that harm water quality all the way to the Pacific Ocean, more than 190 miles away.

This project will be the most significant dam removal and river restoration effort in the world – never before have four dams of this size been removed at once which inundate as many miles of habitat (4 square miles and 15 miles of river length), involving this magnitude of budget (approximately $295 million) and public works.

More than 40 stakeholders – including tribes, irrigators, commercial fishing interests and conservationists – helped craft the original Klamath agreements to remove the dams, restore habitat and resolve decades-long water management disputes. Funding for the project is coming from $200 million collected from PacifiCorp customers in Oregon and California and up to $250 million (if needed) from California through Proposition 1 (Water Bond) passed by voters in 2014.

In 2008, the Public Utilities Commissions in Oregon and California concluded that removing the dams, instead of spending more than $500 million to bring the dams up to 21st century safety and environmental standards, would save PacifiCorp customers more than $100 million. In addition, PacifiCorp has installed more than 10 times the generation capacity of these dams in renewable wind and solar facilities over the past decade.

In 2010, we forged historic agreements among more than 40 Klamath basin stakeholders to remove the dams, restore habitat and resolve decades-long water management disputes. These settlements required Congress to approve the agreements by December 31st, 2015. Congress failed, and the agreements expired.

The new agreements retain the original target to remove the dams by 2020, but the path no longer goes through Congress. Instead, PacifiCorp will seek approval from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to transfer ownership of the four dams to a new non-profit called the Klamath River Renewal Corporation, which will apply to FERC to surrender and remove the dams in 2020, as originally planned. The KRRC will be governed by a board of directors made up of representatives chosen by American Rivers and our conservation partners, as well as directors chosen by the federal, state and tribal governments and representatives of the agricultural community.

Today we are celebrating this major step toward renewing the Klamath River and the fish and water quality that tribes, commercial fisherman and communities along the river depend on, but tomorrow we will get back to work on the many things left to do to succeed by 2020. This includes working with our tribal and agricultural partners in the upper basin to achieve the water rights, restoration and power related provisions we jointly committed to in 2010 but were put in jeopardy by Congress’s failure at the end of 2015. American Rivers is committed to bringing the benefits of such home grown, collaborative solutions to all the communities that depend on a healthy Klamath River.

With news that the Klamath River restoration project is back on track, many are wondering: is this the world’s biggest dam removal project?

That depends what you’re measuring. There have been projects with taller dams or more miles of habitat restored – but when you add it all together, the Klamath is arguably our nation’s most significant dam removal and river restoration effort.

Here’s how the Klamath compares to other projects:

Tallest?

Elwha River, WA | Photo: Tom O’Keefe

The four dams on the Klamath are big, but still not the tallest when it comes to dam removals.

The tallest dam on the Klamath is Iron Gate, at 173 feet high.

But Glines Canyon Dam, which came down a couple years ago on Washington’s Elwha River, was 210 feet tall.

Number of dams?

Other rivers have benefitted from multiple dam removals. For example, ten dams were removed on the Milwaukee River and five on the Baraboo River in Wisconsin. Six dams were removed on the Des Plaines River in Illinois.

But none of these dams were as big as the four dams on the Klamath.

Miles of habitat?

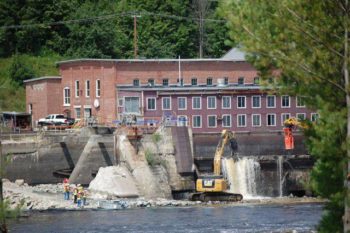

Veazie Dam breach on the Penobscot River, ME

The Klamath reservoirs total 15 miles, with four square miles of inundation. These are big reservoirs, with serious water quality impacts.

When the Klamath dams come down, salmon will have renewed access to more than 300 miles of historic habitat.

By comparison, the Elwha dam removal opened access to roughly 70 miles of habitat.

On Maine’s Penobscot River, removing two dams (Great Works in 2012 and Veazie in 2013) and installing fish passage at others has opened nearly 1,000 miles of habitat to migratory fish.

Price tag?

The cost of the Klamath dam removal and restoration will likely be around $340 million including insurance. The Elwha project cost roughly $324.7 million and the Penobscot project had a price tag of $54 million.

Overall significance?

On the Klamath, never before have four dams of this size been removed at once which inundate as many miles of habitat, involving this magnitude of budget and public works. More than 40 stakeholders – including tribes, irrigators, commercial fishing interests and conservationists – helped craft the Klamath agreements to remove the dams, restore habitat and resolve decades-long water management disputes.

The Klamath isn’t just a dam removal project, it’s an effort to improve water management across the basin and revitalize fishing, farming and tribal communities.

When you consider all of the aspects of the Klamath effort, it definitely stands out. American Rivers is proud to be part of it and we’re dedicated to continuing the hard work to keep the project on track, with dam removal beginning in 2020.

It’s a really exciting time for the Waccamaw River Blue Trail! We have a strong partnership with a local chamber of commerce that has worked over the last several years to promote ecotourism and build support for conservation along the Waccamaw River Blue Trail, South Carolina’s only National Water Trail. To help further improve ecotourism to the Waccamaw River and Georgetown County, we have worked with our partners to connect tourists, the community and area businesses together and demonstrate the importance of the Waccamaw River to the local way of life and economy.

The success of this effort has been fantastic and continues to demonstrate how healthy rivers like the Waccamaw are not only amazing for community livability and sense of place, but are also local economy drivers. This April, Georgetown County is one of the host sites for the 2016 Bassmaster Elite Series tournament, one of the premier freshwater fishing tournament series in the world. Hosting cities have seen economic impacts of more than $2 million. In Georgetown County, tournament water will include the Waccamaw and four additional rivers that are reachable from the launch facility and converge in the Winyah Bay.

While it will be fun to watch what the professionals bring in at the tournament, the community is also taking full advantage of the Waccamaw River’s fishing. Water levels have dropped, and fish are biting left and right. Locals are taking full advantage of this time of year and returning to the best spots along the river, while visitors enjoying the spring weather are experiencing the Waccamaw for the first time. The Waccamaw River Blue Trail map, available at local chamber visitor centers is a great resource to help plan a beautiful paddle or a fishing excursion on the blackwater river.

All of these efforts are aimed at building support for increased river recreation in the region and promoting enhanced conservation along the Waccamaw. Last summer we released a short film featuring the Waccamaw River Blue Trail promoting the exciting opportunities to explore the river and the importance of it to the region. Through partnerships with local businesses and the Chamber of Commerce, we are helping to build a larger and more diverse constituency that recognizes the economic, recreation, and conservation values a healthy Waccamaw River provides the community.

As an avid cross-country skier and all-around winter sports enthusiast, seeing a fresh blanket of snow in the Sierra Nevada is grounds for excitement. The snowpack is also great news for our rivers and water supply in California. But a hefty snowpack also means challenging conditions for monitoring winter greenhouse gas emissions in Sierra meadows, including sometimes digging through five feet of snow to access the meadow surface and collect samples.

Digging through winter snowpack is just one component of an ongoing project to monitor greenhouse gas emissions in several meadows in the Tahoe National Forest. This effort is being led by Nevada City’s South Yuba River Citizens’ League (SYRCL) as part of their Yuba Headwaters Restoration Program. The project is part of a larger meadow restoration and research effort called the Sierra Meadows Research and Restoration Partnership. The partnership includes 10 organizations/agencies (including American Rivers) pursuing restoration and coordinated monitoring on eight meadow complexes across the Sierra Nevada, in order to demonstrate whether restoring a meadow results in a net reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. The partnership received funding for this effort through the California Department of Fish and Wildlife’s (CDFW) Wetlands Restoration for Greenhouse Gas Reduction Grant Program, CDWF’s first distribution of funds from California’s cap-and-trade program.

As part of American River’s partnership with SYRCL through the Sierra Nevada AmeriCorps Partnership, once a month I work with employees, fellow AmeriCorps members, and volunteers from SYRCL to conduct the greenhouse monitoring at SYRCL’s restoration sites. It may be hard to imagine how we go about measuring gases—how do we trap invisible air and measure its contents? After hiking into the meadows (and digging snow in the winter months), we set up circular collars in the ground, attach “chambers”, or lids, and use a syringe to pierce the chamber and draw up gases. After emptying the syringe into a sealed container, we move onto the next flagged site, cycling through so that we visit each chamber three times, spaced out by 15-minute intervals. In addition to helping SYRCL with their monitoring, American Rivers is also partnering with the Sierra Foothill Conservancy to collect data for restoration at Bean Meadow in the Merced watershed.

So how does this project improve the health of rivers? By gathering data to show that meadows sequester carbon, government agencies and organizations may procure funding to further study and restore these areas. This will improve habitat for native plants, fish, and wildlife, in addition to increasing water storage capacity in the meadows. Meadows are often located in a river’s headwaters, influencing the health of the rest of the river downstream. In the Sierra Nevada, healthy, restored mountain meadows play a huge role in the clean water of our beautiful rivers, and provide resiliency in the face of climate change.

Check out the photos below to get an idea of how the monitoring works, and a list of some of the work American Rivers does to assess and restore mountain meadows.

On a recent run on a mountain trail near North Carolina’s Blue Ridge Parkway, my wife and I came upon a pretty dramatic sight. Just about 30 yards downhill from the Parkway, there was a large drain pipe with the outflow frozen solid. Where you might normally assume that this frozen waterfall would be crystalline white, it was far from it. Instead, it was more of a “burnt orange”, unlike any natural color around it.

While I did not take a sample to find out what was causing the orange color (perhaps a combination of iron rust and road deposits including oil and gas from passing cars), what was most striking was that even in this remote area of a protected landscape, there was enough pollution and trash on the road to dominate what you would expect to be a natural setting. And while we normally would not be able to visibly see what was being swept into the pretty little stream below, there it was literally frozen in time.

The stream ultimately flows into the New River, then the Ohio, then the Mississippi. Thinking of how many hundreds of streams like this bring this polluted runoff to the many towns and cities along that route makes it even more important to address it wherever possible.

Peter Raabe, our North Carolina Director, described polluted stormwater as one of the biggest problems facing our streams and said that in most places there is no treatment to purify the water prior to it getting to our streams and ultimately our water supply. That was certainly the case here, and now my wife and I have a stark image to remember that by.

The past week has presented a crazy wave of both good and bad news for Minnesota’s recent endangered rivers— the St. Louis River (listed in 2015) and the Boundary Waters (listed in 2013). Both of these river systems were included on our lists of America’s Most Endangered Rivers® due to the threat of sulfide-ore mining. This type of mining releases copper and nickel bound up in sulfide-bearing rock, and commonly results in acid mine drainage and increased levels of heavy metals and sulfates in downstream waters. Allowance of this type of mining in the St. Louis River and Boundary Waters regions of Minnesota will ruin wild places and contaminate water for people, fish and wildlife.

What’s happening with the St. Louis River?

Now we come to the bad news. On March 3, following the production of an Environmental Impact Statement, the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR) decided to allow PolyMet to move their mining project forward to the permitting stage. In response, our partners at Minnesota Environmental Partnership said, “We are extremely disappointed in the DNR’s determination that the PolyMet project is ready to move to the next stage. The PolyMet project proposal doesn’t protect our lakes, rivers, and streams. Minnesotans don’t accept polluting our Boundary Waters, Lake Superior, and other treasured waters. Minnesotans don’t believe that the international mining companies that own PolyMet will effectively keep their mining pollution from leaking into the St. Louis River, the largest tributary to Lake Superior, for the next 500-plus years that will be required.”

“No operation of this type has operated and closed without polluting nearby lakes, rivers, and streams. Furthermore, predictions in the final environmental impact statement are flawed, and based on bad data and incorrect assumptions, without real-world experience. Those inaccuracies are putting all Minnesotans at risk and threaten the environment and public health. This is a bargain-basement mining plan that relies on outdated technology and a flawed tailings basin. Sulfide mining in a water-rich environment like Minnesota is not worth the high-risk gamble.”

Is there better news for the Boundary Waters?

Fortunately, there is something positive to report on mining in the Boundary Waters. On March 6, Minnesota Governor Mark Dayton sent a letter to the Chief Operating Officer of the Twin Metals mining project proposed in the Boundary Waters watershed. He noted, “I have grave concerns about the use of state surface lands for mining related activities in close proximity to the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCAW)… I have an obligation to ensure it is not diminished in any way. Its uniqueness and fragility require that we exercise special care when we evaluate significant land use changes in the area, and I am unwilling to take risks with that Minnesota environmental icon.” The Governor noted that he has informed the U.S. Bureau of Land Management, which is reviewing Twin Metals’ expired mineral leases on national forest lands adjacent to the Boundary Waters, of his opposition to the Twin Metals project. In addition, the Governor has, “directed the DNR not to authorize or enter into any new state access agreements or lease agreements for mining operations on those state lands.”

Where does that leave us?

With Governor Dayton’s statement of support for protecting the Boundary Waters, we celebrate a great victory for that endangered river. We are thankful that the Governor has listened to the public outcry for protecting this special place.

However, the Governor can do more to protect Minnesota’s rivers from harmful sulfide-ore mining. Clearly, the Governor acknowledges the risks inherent in this type of mining. The St. Louis River and its communities, tribes and wildlife deserve the same consideration and protection against sulfide-ore mining. If this project is allowed to proceed, there is no turning back.

Join us for the release of the 2016 report on America’s Most Endangered Rivers®, coming up on April 12!

This year, National River Cleanup® (NRC) is celebrating its 25th anniversary! To help celebrate, we’ve asked Rose Bayless, program assistant at the Arkansas Headwaters Recreation Area (AHRA), to share the story of her cleanup, which is also celebrating 25 years! Over the past quarter century, NRC and AHRA have been working together to help keep the Arkansas River clean for all to enjoy.

On May 21st, the Arkansas Headwaters Recreation Area (AHRA) will observe our Silver Anniversary for the Arkansas River Cleanup/Greenup in the central mountains of Colorado. The AHRA is responsible for a 152-mile stretch of the upper Arkansas River, which begins its 4,200 mile journey to the Mississippi as a bubbling spring emerging from the rocky Mosquito mountain range north of Leadville. It continues to flow past the 14,000 foot peaks of the Sawatch mountain range, picking up snow melt on its way through fertile valleys and rugged canyons, pushing through Browns Canyon National Monument and the Royal Gorge, before it reaches Pueblo and the open plains of Eastern Colorado.

It just comes naturally that folks like hanging out by the “Ark” as locals call it. On any given day of the year, there is no shortage of residents taking quiet pleasure in the sound of the water splashing by – strolling, fishing, throwing stones, kayaking. The AHRA is also host to over a million visitors a year who enjoy a multitude of outdoor activities along the Ark, including whitewater boating, fishing the Arkansas’ Gold Medal Trout waters, hiking, biking and camping.

Rivers are living, breathing creatures with unique personalities all their own, but up until the recent past it wasn’t uncommon for rivers to be taken for granted and ignored, and adjacent neighborhoods became vacant and dilapidated. Then suddenly in the past few decades, people began to see the beauty and character of rivers that had been all but extinguished, and a renaissance began to rebuild and revive riverfront properties and the rivers themselves. These new river visions created thriving economies and sought after residential, entertainment and recreation venues.

Yet in Colorado and throughout the United States, all this old and new use produced myriad trash and waste along and in our rivers. The mindset was that somehow it would magically disappear, but it didn’t disappear, and we were left with the reminders of mindless behaviors.

Rather than considering all this garbage a problem, the AHRA saw this as an opportunity to build an alliance among the communities and residents along the Ark by creating an annual “river fest” devoted to improving the health of the Arkansas River and restoring its habitat, wildlife and scenic value. It just so happened that the AHRA organized our first river cleanup in May of 1992, the same year that National River Cleanup was established.

Getting this effort started was a daunting task. How do we organize folks in 3 counties, 8 towns and all the rural mountain enclaves to come together for the common cause of trash cleanup? First we had to pick a date after the snow had melted but before the Ark began to roar with run-off, and mid-May was and still is the time. Because the AHRA encompasses such a large geographic area, we involved the cities, counties, their recreation and parks departments and as many other organizations as we could. We invited all the residents too.

[metaslider id=31465]

Food always seems to be a draw, and a volunteer picnic at Riverside Park in Salida was included in the plan, with local businesses donating food and services. Music also is a proven attraction, so we added a band to the mix and threw in a parade as a fund raiser to benefit another river event in June. A trash contest created some lively competition for the weirdest garbage of the day, and each year people hunt for that special something that defies definition.

The local waste management company donated a couple of very large dumpsters, commercial rafting companies donated staff and boats to scour the river, and local radio stations provided advertisement and live coverage. Of course, trash bags are a must, and the awesome “official” River Cleanup bags did the trick for all 250+ volunteers who picked up trash in the morning and enjoyed food and music in the afternoon.

This is how the Arkansas River Cleanup/Greenup (CUGU) was born, and this recipe is still a hit and going strong 25 years later.

As I look back on the accomplishments made over the years, the one thing that stands out most is the increase in public stewardship. AHRA and our partners have instilled the importance of a litter-free environment not just for the pleasure of people, but for maintaining healthy ecosystems. This is where the “Greenup” comes in, because picking up trash promotes healthy flora. Although we have our annual River Cleanup event, the really cool thing is that people don’t wait for May to do their part; they are cleaning up every day! Splinter groups have also branched out to organize their own cleanups throughout the year.

Spring is just around the corner, and folks are already asking “When is River Cleanup?” This seems ironic since we have a foot of snow on the ground and even in May we can’t be sure if it will be spring or not. What we can be sure of is the Ark will be ready for us snow, rain, wind or shine, so it’s time to start gathering the troops. Some of these faithful volunteers are no longer with us, but their love for the Ark lives on. Thank you everyone, and let’s get started!

It would be challenging to find anyone who claims that the Grand Canyon is not one of the most awe-inspiring and magnificent landscapes on the planet. Although, according to Yelp, some people may not fully appreciate the extent of its awesomeness, most people, and certainly the majority of the 5.5 million visitors a year would attest, it is a pretty neat place.

In 2007, I was fortunate to walk across the canyon, rim-to-rim, with a small group of intrepid hikers. The instant your boots cross the threshold between the flat benches that form the rim and edge of the steady descent into the canyon itself, your perspective on everything changes – the crunch of your footsteps on the gravel becomes much more audible, the bounce of your pack as the elevation declines becomes a bit more rhythmic, and you start to notice things that you can’t see from the rim – the nooks and crannies that give a place with so much grandeur and expanse it’s character and romance. The Grand Canyon sits smack dab I the middle of a huge, dry, high-altitude desert, but the intimate spaces, the seeps, springs, and waterfalls that cling to life in this harsh world, provide the life and imagination a place to thrive, survive, and prosper.

As author Kevin Fedarko proclaims, the Grand Canyon should be one of the most valuable, and protected, parcels of real estate in the country. As a World Heritage Site and one of the Natural Wonders of the World, the landscape has earned the accolades and respect around the globe. But as he also points out, the canyon itself is surrounded by threats from all four points of the compass and above. Because of the unprecedented assault on the sanctity of the canyon, American Rivers teamed up with local partner Grand Canyon Trust and listed the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon as Americas Most Endangered River in 2015.

The threats we identified in the listing were daunting – a proposal to build a resort development on the East Rim of the canyon, next to one of the most sacred sites to nearly a dozen Native American tribes, where a tramway would shuttle up to 10,000 people per day down to river level, and a restaurant and gift shop would await their money. Uranium mining around the circumference of the park, which currently and historically has created a pathway for radioactively contaminated water to flow to the Colorado River, was restarting operations. And finally, a proposal to expand the sleepy little village of about 600 residents, Tusayan, into a substantial resort destination, with 2,200 new homes, a couple million square feet of commercial space, a dude ranch and a European-style spa less than 10 miles from the Park entrance, all without a clear plan of where their water would come from.

Grand Canyon National Park Superintendent Dave Uberuaga has stated that while the Escalade project (the tram) may be the most visible and obnoxious threat to the experience of the Grand Canyon, it was the Tusayan proposal that would cast the longest term and most irreparable harm to a wide expanse along the South Rim. Decades of hydrologic study has already linked existing groundwater withdrawal from Tusayan as diminishing the natural groundwater flows within the canyon itself. This groundwater is what feeds the life-sustaining micro-oases tucked within the small spaces along the South Rim. Places like Hermit Springs, Indian Gardens, and the blue waters of Havasu Falls – features directly at risk from irreversible harm to the groundwater along the South Rim.

But since we listed the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon as Most Endangered in 2015, two significant things have happened. First, in May of 2015, newly elected Navajo Chairman Russel Begaye declared that the tram project would not happen on his watch – at least if he had anything to do with it. Last week, the Forest Service flatly denied the town of Tusayan’s application for right-of-way permits for roads and utility easements that would have cleared a major obstacle for the expansion to move forward. Without these easements, the town does not have permission to develop across Forest Service land, which surrounds the town on all sides.

Although representatives from the development group in charge of the town had stated publicly that they would not use groundwater for the expansion, almost nobody believed that they had any other option. On top of that, Stilo never put forth a comprehensive, public plan for how they would provide water to the increased number of thirsty mouths, while protecting the fragile groundwater directly connected to the canyon. As a result, when the Forest Service opened the public comment period and held public meetings in the area to gather feedback on the project, the vast majority of the comments they received were against the proposal.

According to Kaibab National Forest Service Supervisor Heather Provencio, they received more than 105,000 petition signatures, as well as more than 35,000 letters on the proposal, with the vast majority of those opposing the proposed roads and infrastructure.

You spoke out. The Grand Canyon won.

When I think back to my traverse across the canyon, it is the kind features that were spared by this decision that stand out the most. Ribbon Falls (sacred to the Zuni), Indian Gardens and Havasu Falls (both important to the Havasupai), Elves Chasm, and so many more. These are the places that cool the skin and refresh the mind. These are the places of maidenhair ferns and Canyon Tree Frogs. These are the places of intimate beauty.

The very character of the canyon is what we all just stood up for – but as David Brower once noted, the immediate threat may be gone for now, but the place where the project was proposed does not disappear. The Confluence will not go away, Tusayan will not go away (and there is certainly a need for more hotel beds near the Park), the Uranium in the ground will not go away. Case in point – there is scuttlebutt on the Navajo Reservation that the proponents of the tram project are back, and leaning on local legislators to push through permissions to build the project. But the message is that if development is to happen near one of our most treasured natural landscapes, that it must be done in a thoughtful, deliberate, and public way in order to protect the very reasons why the place is so precious to begin with. Without that, deterioration of the experience and quality of our most important natural landscapes is a non-starter.

This article was written by David Kuczkir and appeared originally in Canoe & Kayak Magazine’s digital edition.

The juggernaut of these waterways is the Ashley River, a South Carolina State Scenic River. Ashley’s 24,000-acre historical district, with 130 historical national landmarks, is one of the largest in the country. The network of waterways is an all-year playground for canoeists and kayakers. What’s more, paddling Ashley is tantamount to traveling back to the days when everyday life depended on the ebb and flow of the tides.

The 36-mile Ashley River is tidal and flows from her swampy headwaters in Berkeley County, South Carolina, to the famed steepled city, Charleston. In February 2014 the conservation organization American Rivers anointed Ashley a Blue Trail. According to American Rivers Senior Director Gerrit Jöbsis, “A Blue Trail is a waterway adopted by a local community that is dedicated to improving family-friendly activities, such as fishing, paddling, and wildlife-watching, and conserving riverside land.”

The Ashley River Blue Trail (ARBT) is 30 miles in length, from Sland’s Bridge to the mouth of Towne Creek, and is split into the north and the south trails.

The sweet spot of the ARBT, and of the river, is a 15-mile swath between Drayton Hall, a pre-Revolutionary plantation, and Bacon’s Bridge. Paddling upriver, the first six miles is a no wake zone, home to three world-renown riverside plantations: Drayton Hall, Magnolia Plantation and Gardens, and Middleton Place.

The 1738 main house on Drayton Hall, framed in romantic early-English gardens, is remarkably the only intact plantation house on the river. The 24 other significant plantations were either burned in the Revolutionary or the Civil Wars, or destroyed in the 1804 hurricane or the 1886 earthquake.

Magnolia Plantation and Gardens, founded in 1672, has the oldest naturally landscaped gardens in America. Thick with flowering camellias, azaleas, crape myrtles and fragrant magnolias that pop throughout the seasons, the gardens are the birthplace of the American tourism industry.

Middleton Place was established in 1755. Visitors from around the globe pay homage to the symmetrical Butterfly Lakes (twin lakes that resemble butterfly wings) and the meticulously manicured gardens. The Garden Club of America has called the 65-acre oasis “the most important and most interesting garden in America.”

The river affords gorgeous vistas of the gardens, and of the Drayton house.

The Ashley River Heritage Trail (ARHT), a trail within a trail, is a 5.5-mile float between Middleton Place and Bacon’s Bridge. “It stretches into the upper reaches where the water’s skinny, more suitable for paddlers,” explains Jöbsis. The surroundings are intimate, dimmed by the canopy of massive oak boughs snaking out over the slow-flowing, tannin-colored water.

The ARHT showcases eight archeological sites comprised of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century shipwrecks and landings that are all exposed at low tide.

Near the northern terminus lies a well-preserved 1697 trading town, Colonial Dorchester State Historic Site. Archeological digs are ongoing. The 1757 fort is the best preserved tabby fortification in the country. Portage along the bank then explore this unique historical landmark.

Both trails only scratch the surface of Ashley’s repertoire of things to do and see. According to Jöbsis, “The great thing about the Ashley is it’s tidal.” Plan the tides right and you can cover a lot of river in one day. Jobsis’ enjoys paddling Ashley’s myriad of creeks, “They are an excellent sanctuary for paddlers from motorboats and allows one to get lost among the tidal marshes.”

If you Go:

The 55-room Inn at Middleton Place is located on the scenic Ashely River. Rooms have fireplaces and floor-to-ceiling windows that afford sweeping vistas of the Ashley and of the sunrise. Call 800-542-4774, 843-556-0500 or e-mail reservations@theinnatmiddletonplace.com

Outfitters and Guides

Sun and Moon Kayaking provides guides and outfitting services for kayaking. Call 843-452-6917 or e-mail mark@sunandmoonkayaking.com

Charleston Kayak Company provides guides and outfitting services for kayaking, canoeing and paddle boarding. Also offered is a unique guided-kayak tour of the Blackwater Cypress Swamp (Nov thru April). Call 843-628-2879 or e-mail charlestonkayak@gmail.com

Flow Info: NOAA Tide Predictions for the Ashley River

Be sure to check out the Ashley River Blue Trail map to learn where to access the river and find these historic sites and start planning your Ashley River Blue Trail adventure today!

Today’s post is by guest blogger Susan Culp, a consultant serving as Verde River Project Coordinator for American Rivers.

It is a story of deep connections to place. “Wines capture places,” Eric related as he shared the story of his beginnings. The flavors, aroma and textures of a wine can bring back a surge of memories from the place where the fruit was grown.

Wine making in the Verde Valley has bloomed in recent years, with local wines earning recognition among savvy connoisseurs. Once known solely for the red rocks of Sedona, visitors are now discovering the charm of other valley communities, and enjoying the local wines and craft beers produced there.

For many of these budding industries, including Page Springs Cellars, sustainability is a core value, and simply good business. “My livelihood is linked to how I treat the land,” Eric went on, and spoke with pride about the increase in forest habitat and wildlife diversity on his property since he began his vineyard operation. In the arid high desert, sustainable water use is also a critical concern.

For an area that grew up on mining, ranching, and agriculture, the transition of some agricultural lands to more water-friendly grape production has been a boon for sustaining small-scale agriculture in the face of resource scarcity. On average, established vineyards can use about a tenth of the water and enjoy higher profit margins, depending on the grape variety. Data from the Southwest Wine Center has also shown that higher quality grape production trends toward lower water use or even dry-farmed conditions for the vineyard. It is economically rewarding as well, with area wine production generating about $25 million annually, employing over 100 people, and prompting $6.5 million in spending at tasting rooms, vineyards, and wineries.

Dating back as far as the 16th century, Spanish settlers in Southern Arizona tended vineyards and made wine, and in the 1800’s European settlers along Oak Creek produced wine for area miners. Arizona and New Mexico once combined to have more vineyards than California, but with Arizona as an early Prohibition supporter, its wine industry ceased with passage of the 18th Amendment in 1920.

In the 1970’s, viticulture slowly began to reemerge in Arizona. The first wine-making license was issued in Yavapai County in 1981, and over the next three decades, dozens of new vineyards were planted. While California wines may grab the spotlight, the climate and soils of Arizona are uniquely suited for vineyards. Alkaline soils layered with minerals and marine sediments mingle with volcanic intrusions, perfectly blending with climate and elevation.

While the Verde Valley remains predominantly rural in character, it is a growing region, largely due to its natural amenities and attractions. Vineyards have been an economically viable means to preserve local agricultural resources, open space and wildlife habitat in the face of growth pressures. Growth also creates challenges to protecting the Verde River, one of the last free-flowing, perennial rivers in Arizona. By focusing on a less water-intensive, valuable crop such as grapes, the wine industry is doing its part to protect the natural resources of this vibrant destination.

Popular tourist excursions, such as “Water to Wine” tours, highlight creative ways economic growth and outdoor adventures are paired in the Verde Valley. Imagine paddling a desert stream in the morning, then reflecting upon the adventure under tall cottonwoods with fellow paddlers at a local vineyard for the afternoon.

The Verde Valley wine industry is increasingly touching on three important tenets – protection of environmental values, creation of economic benefits, and supporting social opportunities. Raising a glass of superb locally produced wine can be one of the most enjoyable ways to do your part for a sustainable future.

Our new film, “Walt,” shares his story and captures his determination to restore the river.

When it comes to news about the drought in California, we’re all tired of “fish versus farms” stories that offer false choices and no solutions. Enter Walt Shubin, a farmer who has been fighting to restore the health of the San Joaquin River for decades. Walt remembers the river when it was wild, when its waters flowed, and it was home to abundant fish and wildlife.

[su_quote cite=”Walt Shubin”]I’ve had a love affair with the San Joaquin River since the first time I saw it. I feel that all rivers are national treasures. When that river was wild, it was so beautiful. It was sacred, spiritual. It was a feeling I can’t even describe. [/su_quote]

Learn more and find out how you can help the San Joaquin River, which American Rivers named America’s Most Endangered River® in 2014.

“Walt,” produced by filmmaker Justin Clifton, is part of our series of films using creative storytelling to inspire river conservation. First, we released Parker’s Top 50, about a child’s action-packed adventures along some of the Northwest’s most beautiful rivers. Next came The Important Places, an award-winning film about a father and son reconnecting on a Grand Canyon river trip. This summer, we released Flint, featuring the beauty of Georgia’s Flint River.

All of these films were featured at the Wild & Scenic film festival – and we have more exciting film projects planned for 2016.

[su_youtube url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/wtRWnAOnf7g” width=”1020″ height=”580″]