Guest post by Brian Smith is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the St. Lawrence River.

Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River provide drinking water to several million people, support multi-billion dollar industries, offer unparalleled recreation and fishing opportunities, generate renewable hydroelectric power, and are home to an impressive array of wildlife. Perhaps most importantly, the river and lake enhance the quality of life for everyone in the region. It is no wonder then, that the residents of New York State support modernizing an outdated management plan that is slowly killing the health of the lake and river.

As a grassroots organization working to protect the environment throughout New York State, Citizens Campaign for the Environment (CCE) has lead a large-scale public outreach campaign on the issue of Lake Ontario and St. Lawrence River water level management over the past few years. We conducted direct public outreach in numerous communities along the south shore of Lake Ontario up to the St. Lawrence River.

What did we find when we spoke directly with families across the region about this issue? Whether it was the mother with small children that loves taking trips to the beach on weekends, a recently retired man that spends countless hours on a boat fishing, or the college student that cares passionately about protecting the health of our waters for future generations, we spoke with a broad range of New Yorkers that care passionately about the health of our waters and overwhelming support the adoption of Plan 2014.

Members of the public signed petitions, wrote letters and emails, and made phone calls to key government officials in support of Plan 2014, contributing toward the nearly 23,000 expressions of citizen support that have been generated by CCE and our partners in recent years.

Despite this growing wave of support for Plan 2014, the federal governments of the U.S. and Canada have yet to adopt the plan. U.S. Secretary John Kerry and Canadian Foreign Affairs Minister Stéphane Dion can help restore the health of the lake and river with the simple stroke of a pen. We can’t let up now— they need to know that we can’t wait any longer. We need your help to demand action today!

Brian Smith is the Associate Executive Director for Citizens Campaign for the Environment (CCE).

Guest post by Daniel Macfarlane is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the St. Lawrence River.

The St. Lawrence Seaway and Power Project, built by Canada and the U.S. between 1954 and 1959, blended a deep-draught navigation system with a massive hydroelectric development. The dams and control works built as part of this project, explained in detail in my book Negotiating a River: Canada, the US, and the Creation of the St. Lawrence Seaway, turned a large stretch of the international river into a lake, flooding out some 40,000 acres – and the residents – on both sides of the U.S./Canada border.

We shouldn’t assume that the Seaway is a success story. It never came close to living up to predictions nor to paying for itself. Moreover, the project had many ecological ramifications, which included facilitating the passage of many invasive species.

The method of regulating Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River is one of the crucial ecological legacies of this megaproject. Water levels were kept within a specified and predictable range – the “method of regulation” – based on the needs of various competing uses: commercial shipping, hydropower, port users at Montreal, and property owners on Lake Ontario.

NRC Research News

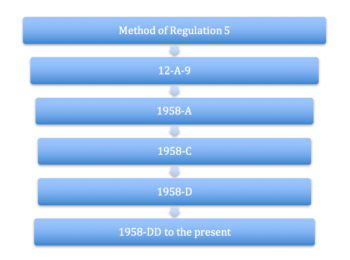

However, the process of establishing the initial method of regulation during the 1950s and 1960s was plagued by engineering errors, guesses, and partisan politics. Engineers and planners, overly reliant on giant models, admitted that they weren’t really sure about what they were doing. As a result, they strove to attain levels, in their own words, “as nearly as may be.” After going through several provisional methods of regulation (see image below) during the construction of the Seaway, engineers arrived at method 1958-D, which compresses the water range to about 4 feet. Unfortunately, significant problems with natural water supply soon developed, since Great Lakes water levels naturally fluctuate. Thus the method of regulation 1958-DD, a tweak of its predecessor, was adopted.

It soon became apparent that steady water levels were detrimental to the St. Lawrence ecosystem, especially coastal wetlands, littoral zones, and fish populations. The natural variability that happens during seasonal changes to an unregulated river, even one with a steady flow like the St. Lawrence, are very beneficial for shoreline ecology and wildlife.

Many St. Lawrence communities and environmental advocacy groups strongly support the International Joint Commission’s (IJC) proposed Plan 2014. However, Seaway administrators, shipping interests, and some shoreline owners worried about erosion on their property are opposed. In fact, complaints from Lake Ontario property owners were partially responsible for the flawed system that was put in place a half century ago.

The current method of regulation is antiquated, recognized by the designation in April 2016 of the St. Lawrence as one of America’s Most Endangered Rivers®. The history of trying to regulate the St. Lawrence River shows that there is an underlying conceptual flaw in the notion that we should control the hydrological regimes on rivers and lakes. Plan 2014 is a major step in the right direction.

Dr. Daniel Macfarlane is an Assistant Professor of Environmental and Sustainability Studies at Western Michigan University.

Guest post by Dr. Douglas Wilcox is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the St. Lawrence River.

With 30 years in federal service, more recently with the U.S. Geological Survey, and the last eight years at Brockport, I’ve studied and worked on Great Lakes wetlands my entire career. The underlying theme in all of my research findings has been that hydrology (lake level) is an overriding force that controls wetland function. Needless to say, I thoroughly understand the ways that lake-level fluctuations affect Great Lakes wetlands and how water-level regulation affects the St. Lawrence River and Lake Ontario.

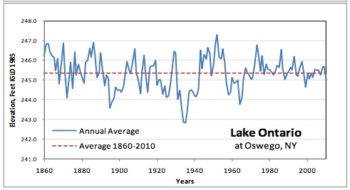

Lake Ontario Levels

During that professional career, my research team developed a 4,700-year paleo record of lake levels in lakes Michigan-Huron that shows regular patterns in fluctuations, with high/low cycles roughly every 32 years and longer-term cycles of about 160 years. This variability has shaped the evolution of the vital native species that grace Great Lakes wetlands, including Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River.

Put simply, variability matters.

So, how do these fluctuations affect wetlands and impact wildlife?

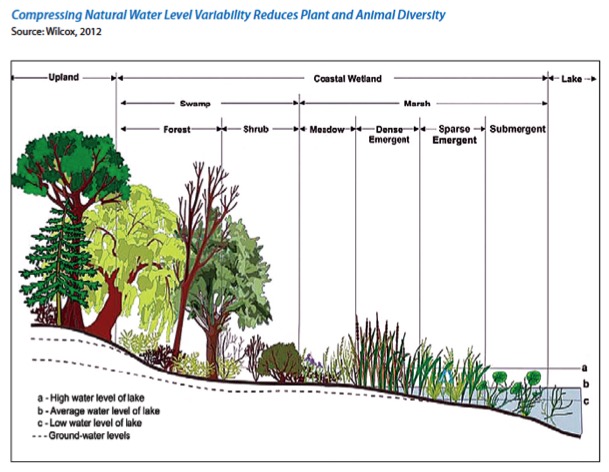

Plants Water Levels

If you look at the horizontal line A in the figure above, you will see the highest high Lake Ontario experiences. Anywhere above that line never gets flooded.

Horizontal line C in this figure shows the lowest low Lake Ontario will experience. Anything below that line always has standing water on it.

The broad area between the lines is the action zone. It gets flooded sometimes and dewatered other times. When water levels rise and fall throughout Lake Ontario’s natural cadence, the system remains in balance.

During periods when high lake levels are naturally higher, invasive plants like cattails are flooded out, as are invading trees and shrubs from the upland.

During periods when lake levels are naturally lower, sediments and the seed bank are exposed, allowing native species that have deposited their seeds a chance to grow. The sediments also become too dry to support invading cattails, providing a competitive advantage to wet meadow plants that can tolerate low soil moisture.

This has been happening for thousands of years, and the biological communities, both plant and animal, have evolved to depend on those conditions.

So, what’s the problem?

The damaging and unnatural water-level regulation plan instituted after the Moses Saunders Dam was built has thrown a wrench in this natural cadence. This plan attempts to keep year-to-year water-level patterns static, which is the absolute worst thing you could ever do to a Great Lakes wetland. The impacts are striking:

- In some areas, once sandy beaches have been replaced with shoreline armoring to protect property from high lake levels, while the shoreline never receives the periodic lows needed to replenish the beach. Shoreline processes are disrupted, and barrier beaches that protect some of the wetlands lose the sand they need.

- Areas at higher elevations in wetlands that are covered by wet meadows, a major component of coastal wetlands, have been greatly reduced because they have lost the competitive advantage provided by periodic low lake levels during the summer growing season.

- Cattails, which cannot tolerate low lake levels, invaded the wetlands and replaced the wet meadows. Without natural variation in water levels, invasive cattails have created monocultures where vibrant ecosystems once stood.

- Northern pike adults feed in these wetlands. The adults spawn in the flooded wet meadow; the young live and grow up in wetlands. When water levels are kept low over the winter and early spring, there is no water for the northern pike to access wetlands and spawn. Consequently, northern pike populations have been reduced by 70% under the current water-level regulation plan.

- Muskrats, an important species that eats cattails and uses them to build houses, are now rare in Lake Ontario and St. Lawrence River wetlands because their houses are left high and dry in the winter when the current water-level regulation plan draws winter lake levels down too low. When muskrats cannot fulfill their natural role in eating and controlling cattails, there is a lot of reduction in fish and wildlife habitat.

This is why the new water-level regulation plan, Plan 2014, is so important.

Plan 2014 will ensure that water levels are managed in a scientifically-defensible manner. Plan 2014 includes triggers that change to reflect the season. In the summer, the triggers reflect high lake levels that could damage property; in the spring and fall, the triggers reflect low lake levels that could impact boating and other activities. If lake and river start to approach these seasonally-adjusted trigger levels, the International Joint Commission’s Board of Control will act to regulate water levels accordingly and protect shoreline-property and other interests before the triggers are reached.

More importantly, during years with low water supplies to the Lake Ontario watershed, Plan 2014 will allow lake levels to be lower in the summer rather than keeping them unnaturally high, thus benefitting wet meadows rather than cattails. During years with adequate water supplies, Plan 2014 will allow winter and spring lake levels to remain slightly higher to support fish and muskrat populations. Plan 2014 seeks to reestablish more natural environmental conditions while continuing to provide support for other interests and should be supported by everyone.

Dr. Douglas A. Wilcox is the Empire Innovation Professor of Wetland Science at SUNY—The College at Brockport. Dr. Wilcox is an expert in wetland ecology, with an emphasis on the influence of hydrology, climate change, and human disturbance on wetland plant communities.

Guest post by A. Charles Parker is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the St. Lawrence River.

The St. Lawrence River and Lake Ontario are ecological gems that have offered enjoyment and outdoor sporting opportunities to hunt, fish, and trap since before the countries of the United States and Canada were established.

These opportunities are now at risk.

That is why the New York State Conservation Council is calling on the U.S. State Department and the Canadian Ministry of Global Affairs to accept Plan 2014 and begin the restoration of the St Lawrence River and Lake Ontario. To correct the problems that have been created by the Management Control Methods enacted on these bodies of water in the 1950s, we must act now.

Man’s ability to manage the St. Lawrence River and Lake Ontario through dams and other water level control processes is substantial and amazing. The methods established to do so in the late 1950’s yielded a better waterway for commerce and a source of hydroelectric power, and many will say it has been a great success story. However, the passage of time has also highlighted problems that need to be addressed.

The outdated management strategy of the 1950’s plan does not allow for the natural variability in water levels and flows essential to maintain a healthy river. Instead, current management significantly limits the range of water level fluctuations. The resulting artificially-constrained water levels have caused a loss of biodiversity in coastal wetlands and significant impacts to many fish species and nesting water birds.

According to Save the River/Upper St. Lawrence Riverkeeper, “More than 64,000 acres of wetlands in the Great Lakes have been gradually starved of their natural biodiversity and morphed into wall-to wall cattail stands. Researchers have found that the wet meadow – a major component of coastal wetlands – has declined by over 50 percent. Black Tern, a state-listed endangered bird species that depends on a diverse marsh habitat, has declined by over 80 percent. Northern Pike, the top fish predator in coastal marshes, has declined by 70 percent. These species were specifically studied because they are indicators of ecosystem response, and show how far-reaching the impacts have been to the entire river environment.”

Long-term sportsmen in the Upper St. Lawrence region can also attest to witnessing declining habitat for waterfowl and a decline in the quality of the fishery.

Through the principles and management practices promoted in Plan 2014, we can reclaim lost quality habitat for the St Lawrence River without adversely affecting what some see as the advantages gained from the changes created in the late 1950s.

Plan 2014 is based on science and promotes the benefits of healthy, intact wetlands including: improved water quality, stronger fisheries, increased biodiversity and erosion control. Plan 2014, when implemented, will place the environment at the center of decisions about water level regulations on the St. Lawrence River and will be one of the largest wetland restorations in North America.

The time to implement Plan 2014 is now. If we wait much longer we may very well reach a point by which we can never recover.

Charles Parker is President of the New York State Conservation Council, a non-profit with a mission to aid in the formulation and establishment of sound policies and practices designed to conserve, protect, restore and perpetuate forests, wildlife and scenic and recreational areas with especial regard to the state of New York, to the general end that the present and succeeding generations may continue to enjoy and to use these great natural resources.

On June 7th, I had the opportunity to spend the day talking about two of my favorite subjects – rivers and cities. American Rivers, in partnership with The Conservation Fund, hosted a peer-to-peer meeting with delegations from Tucson, AZ, Metropolitan Atlanta, GA and Metropolitan Raleigh-Durham, NC. Delegations included water managers, council members and their representatives and watershed organizations, among others. The goal of the meeting was for participants to learn more about what these cities are doing on One Water, to improve cohesion within their city’s team, and to learn from other cities. We hosted this meeting as part of the US Water Alliance’s larger One Water Summit, and our initiative is part of a larger national effort being funded by the Pisces Foundation.

You may ask, what is One Water?

One Water, also called Integrated Urban Water Management, is a concept that attempts to integrate planning and management of drinking water, wastewater and stormwater in a way that enhances environmental, social and economic vitality. For our rivers, it means working towards restoring or mimicking the natural water cycle in cities.

In other words, we are attempting to get different city agencies, non-profits, and other stakeholders that work on different aspects of water to break out of their silos and work together in a way that reduces pollution to rivers, increase water efficiency, and does so in a way that makes a city more livable. If you are interested in diving deeper, check out our report on the subject, or our Integrated Water Management Resource Center. Our partners at the Water Environment and Reuse Foundation also do a lot of academic research on this topic.

The best way of getting people to think outside the box and out of their silos, is to get them together and talking. While this seems pretty straightforward, it’s surprising how little this type of interaction occurs.

During our peer-to-peer meeting, there were a lot of great ideas passed around, like forming collaborative, official partnerships with other city agencies, putting together integrated plans across departments, and partnering with environmental non-profits to help bring different parties to the table. Many of the participants were excited by the opportunity to talk with and learn from their peers across the country. We were also excited to have the discussions visualized on paper by one of our attendees, Mike Schlegel, from the Triangle J Council of Governments, in North Carolina. The photo here describes the conversation we had around green infrastructure at different scales. You can also see a photo of the group taking a tour of the Clayton County Water Authority’s E.L. Huie Jr. Constructed Wetlands which are a great example of a One Water solution.

Michael Schlegel’s Visual Demonstration

It really was a great event, with a lot of good conversation. American Rivers is looking forward to continuing the One Water conversation and ensuring that rivers and people benefit from better water management.

Today’s post is a guest blog from Buck Ryan, Executive Director of the Snake River Waterkeeper. The Snake River Waterkeeper is a grant recipient of the Connecting Communities to Rivers Grant Program, working to connect their community to the Snake River and its tributaries.

The sun is out, temperatures are up and spring runoff is in full swing. River season is here! Whether you paddle, fish, swim or just enjoy sitting on the banks, rivers offer something for everyone! The Snake River Waterkeeper, a 2016 Connecting Communities to Rivers Grantee, has made connecting with and recreating on the Snake River easier and safer for everyone, with their new Swim Guide App, which you can download today from the Apple App Store or Android Google Store here.

The Snake River and its tributaries weave through communities in Wyoming, Idaho, Oregon and Washington. Residents and tourists enjoy the river for everything from swimming and hiking to paddling. In addition to leading and organizing annual river cleanups, Snake River Waterkeeper also works to keep river users safe while they are out enjoying the river in the summer. Last year, Snake River Waterkeeper began hosting the Swim Guide App, which provides descriptions of and directions to swim sites as well as up-to-date monitoring information about where it is safe to get out and enjoy the Snake River and its many tributaries. Snake River Waterkeeper independently collects information to help keep the app up to date and provide river lovers with the best and safest places to play along the Snake.

Along the Snake River, local communities have started the river season out strong with the Snake River Waterkeeper’s annual spring river cleanup. More than 50 volunteers along 8 different tributaries within the Snake Basin – from Jackson, WY to Pasco, WA – got out to give back and clean up their local river. After the dust settled and landfill weights were compiled, volunteers had removed more than 1,700 pounds of trash from the banks of the Snake River and it’s tributaries. By bringing local individuals together, our cleanups immediately improve riparian scenery, water quality, and stream health while encouraging rural communities to steward local waterways.

On April 20, Executive Director Buck Ryan led a group of 6 volunteers to clean up a section of the lower Owyhee River near Adrian, Oregon. Participants helped shovel nearly 1,000 pounds of remodel scrap from a dump site directly bordering the river. “Why anyone would make an extra effort to haul construction scrap past public landfills and dumpsters to mar a beautiful streambank is beyond me, but we left the place in better shape than we found it. Snake River Waterkeeper will keep fighting polluters on the water and in court until the Snake River and its tributaries are back in the pristine condition they deserve.”

June 1 launched this Snake River Waterkeeper’s ’s 2016 water quality monitoring season. Download the free Swim Guide App today, learn where the best places to swim and enjoy the Snake River are, and check sites before you go to make sure conditions are safe!! Don’t have a smartphone? Check out the online Swim Guide widget here!

Learn more at www.snakeriverwaterkeeper.org and like us on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/SnakeRiverWaterkeeper/.

Guest post by Peter Johnston is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the St. Lawrence River.

Tracing its roots to 1889, Ed Huck Marine has been around for much longer than the Moses-Saunders dam. The business now owned by the fourth generation of the Huck family has seen, first-hand, the damage that poor water level management has had on the environment and area businesses.

Take a moment and think about the indispensable ways the St. Lawrence River impacts our daily lives. Whether it is through recreational boating, fishing, tourism or the simple enjoyment of a healthy river – this great place underpins our economy and stands at the center of our region’s way of life.

My livelihood as a marina operator depends on a healthy St. Lawrence River. The quality of this waterway has made this one of the premier boating destinations in North America.

My son who competes in bass fishing tournaments depends on a healthy St. Lawrence River and its fishery.

Healthier lake and river wetlands will support stronger populations of native fish and wildlife, improving the area’s hunting, angling, and wildlife-viewing opportunities. The Nature Conservancy estimates economic benefits, just from improved wildlife recreation, of $4.0 million – $9.1 million per year.

Plan 2014 will enhance this ecosystem and improve the economy at the same time. Secretary Kerry and Minister Dion need to implement Plan 2014 today.

Peter Johnston is co-owner of Ed Huck Marine, a company located on the St. Lawrence River in the Heart of the 1000 Islands. Since 1889, Ed Huck Marine has been providing area boaters with the finest brands and services available.

Today’s post is a guest blog from Joe Zimbric, A Big Sky Watershed Corps Member with the Blackfoot Challenge. The Blackfoot Challenge is a grant recipient of the Connecting Communities to Rivers Grant Program, working to connect their community to the Blackfoot River.

Nested in the far eastern edge of the Columbia River Basin lies the 2,500 square mile Blackfoot watershed in Western Montana. While the total area is expansive, the watershed itself can be unpacked into dozens of smaller watersheds and sub-drainages, each one with its own reservoir – or more accurately, a reservoir of snowpack.

In the spring, water cascades down from the mountains through thick coniferous forests, sagebrush steppe, and onto the grasslands and croplands where tributaries converge and drain into the Blackfoot River. When viewed from above, the natural fractal symmetry of this extraordinary tributary network of the valley is extraordinarily beautiful and mesmerizing.

Escorted by the mountains, the Big Blackfoot flows about 130 miles, trickling from the high reaches of the Continental Divide before snaking its way along the valley floor. From riffle to run to pool and over and over again, it meanders its way west, supporting everything from the iconic megafauna like grizzly bears, to unassuming microorganisms, to the people who call the Blackfoot valley home. It’s essential to all life here.

I came to the Blackfoot Challenge as an AmeriCorps member in early January from Minnesota, and once I found my bearings and finished gawking at the mountains and wildlife, I set out to help my colleagues build upon an existing citizen science-based watershed monitoring program. Funding, or rather the lack of funding, for monitoring has historically been an issue for small non-profits working with water resources. At the same time, we determined that this type of monitoring program was the best way to bridge the gap with the local community on watershed health and drought response awareness.

We’ve partnered with other area non-profits, local schools, and community volunteers to expand our monitoring capacity and to educate area residents about watershed processes. Currently we have students taking flow measurements on a number of streams alongside other volunteers taking water samples, and we’re building a robust database to support our efforts for years to come. Our volunteers are excited to be participating and they are looking at our changing water resources in a new light and with a greater appreciation. However there is still plenty of work to do.

The Blackfoot has about 50 segments that are impaired for at least one pollutant as defined by the Montana Department of Environmental Quality (including sediment and elevated water temperature). Repairing these streams requires research, restoration, and consistent monitoring. Concurrently, the Blackfoot watershed has struggled with drought conditions in 10 of the last 16 years. Our organization knows it takes community involvement to find solutions to these watershed challenges. Blackfoot Challenge works with an amazing group of partners and stakeholders, and every year we make progress. Our monitoring program is just one piece of a larger undertaking, and an informed and enthusiastic community will continue to strengthen our restoration efforts and promote important drought resiliency work. We appreciate the support of American Rivers in bringing new capacity to the Blackfoot’s community-based drought response program.

Guest post by Rebecca Dolson is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the St. Lawrence River.

In April, the St. Lawrence River was named one of America’s Most Endangered Rivers®.

For over 50 years, the St. Lawrence River and Lake Ontario have been subjected to a water level and flow-management plan that has caused extreme wetland habitat loss and species declines because it did not consider the importance of natural, variable flows.

WWF-Canada’s Watershed Report for the St. Lawrence River shows that the river is facing very high threats from flow alteration, habitat fragmentation, pollution and a high threat from habitat loss. Lake Ontario also faces very high threat levels from habitat fragmentation and a moderate threat from alteration of flows.

The good news is that a new water level and flow management plan already exists. It is called Plan 2014, developed by the International Joint Commission and referred to both the Canadian and United States governments for approval on June 19th, 2014. It is a solution that is good for the environment, the economy and the communities along the St. Lawrence. Plan 2014 would restore more than 26,000 hectares of wetlands along the St. Lawrence and Lake Ontario shorelines, boost hydropower production, and increase the resilience of hundreds of kilometers of shorelines on the Canadian and U.S. sides of the waterway.

More than 22,500 citizens, 42 conservation organizations and 35 business and community leaders have expressed support for Canada and the United States to adopt Plan 2014, but it remains unapproved.

WWF-Canada supports the immediate adoption of Plan 2014 by both governments to benefit the habitats, species and communities that rely on Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River.

Rebecca Dolson is World Wildlife Fund (WWF) Canada’s specialist on freshwater policy. WWF is Canada’s largest international conservation organization with the active support of more than 150,000 Canadians.

Today’s post is a guest blog from Robyn Mattison, Public Works Director and the City Engineer for the City of Ketchum. The city is a grant recipient of the Connecting Communities to Rivers Grant Program, working to connect their community to the Big Wood River.

The Happy Trails project is off to a happy start, with work already completed on two of the thirteen trails slated for rehabilitation, connecting Ketchum residents and area visitors to the Big Wood River.

The City of Ketchum, in partnership with the Idaho Conservation League, received a grant from American Rivers to improve public access to the Big Wood River. Currently, there are 16 Big Wood River access points within city limits, yet only a few are marked with signs and some of the trails are overgrown with vegetation, making it difficult for people to know where they can access the river. The Happy Trails project will improve these conditions, supporting the restoration of trails and riverside land, remove noxious weeds, add signage, mark parking areas and reroute unsustainable trails.

Red Day in Ketchum, Idaho

Community support is a crucial part of the Happy Trails Project. Together with the Idaho Conservation League, we are working to generate support from local businesses and raise awareness with the general community. Jointly, we are facilitating volunteer opportunities to inspire community members to help with trail maintenance along 11 remaining paths.

Keller Williams Sun Valley Realty, was the first group to take advantage of this volunteer opportunity. They were among 134,000 Keller Williams associates worldwide participating in the real estate franchise’s annual RED Day (Renew, Energize and Donate). Its associates donated a day to give back to their local community contributing labor to improve two trails that provide access to a 10-foot angler easement along the east side of the Big Wood River; Bear Lane and Northwood Way trails.

Twenty Keller Williams agents helped to dig paths, remove rocks and brush and spread decomposed granite, a trail base that provides easier access for wheelchair users and those with other mobility issues.

“We were thrilled to perform such a fantastic project for Ketchum,” said Keller William’s Lane Monroe. “Giving back to the community for this type of project is important to us. Public lands access is near and dear to Idahoans.”

There will be plenty of opportunities to volunteer outside this summer with the City of Ketchum and Idaho Conservation League as a part of the Happy Trails Project. How can you lend a hand to improve trails in your community and connect with the Big Wood River?

As I travel around the west I often hear stories from people who are dismayed, aghast, or flatly resigned over the rampant pace of development and how we are losing all of our special places – never to be restored to their wild nature, at least not in our lifetimes. Glen Canyon tops the list; plenty of people yearn for the days when the Colorado River ran free, prior to when the gates slammed shut in the 1960’s. They badly want the place that no one knew back, sometimes at the cost of reasonable discourse about the broad legal and societal situation in the Southwest. The Colorado Basin is a very different place in 2016 than it was in 1922.

Paddling the Yampa River | Sinjin Eberle

But if there is one shining example of a preservation success story, it’s the Yampa River in northwestern Colorado. One of the last major free-flowing rivers in the Colorado Basin, the Yampa serves as both a reminder of what is possible, as well as symbolizes all the reasons that we work so hard to preserve the last wild rivers and restore damaged rivers to their more natural state.

Certainly, the Yampa is not without its scars – David Brower famously pivoted to preserve the Yampa at the expense of Glen Canyon, and as he came to realize the cost those decisions levied on Glen Canyon, he greatly regretted that such a decision had to be made. But others close to Brower have told me that there was really nothing that he could have done; the Bureau of Reclamation was set on damming Glen Canyon no matter what Brower did, and that his true victory was to keep the Echo Park Dam out of Dinosaur National Monument.

Paddling the Yampa River | Sinjin Eberle

I floated the Yampa for the first time a few weeks ago, as part of a trip put together with Friends of the Yampa and supported by O.A.R.S. Rafting. There were 20 of us, and our motley crew of visual artists, writers, conservationists, and policy experts came together to float this river for a few days. We chatted about policy and conservation ethic. We bonded with cold libations around warm campfires at night. We huddled in our tents during a cold, misty rainstorm. We contemplated silently, words not allowed, as we drifted into Echo Park, our gazes cast upon the towering sandstone walls, tracing arcs across the azure blue sky as a solitary raven floated overhead. After a day or two in Yampa Canyon it is easy to be absorbed into the place, and truly understand the pull of wild rivers. They speak to a place much deeper within each of us than anything viewed on a screen or photograph can provide.

The Yampa is also not without its threats. With a thirsty, growing Front Range population, a flowing river with “surplus” water will forever be a development target. But as one of the stronghold rivers for four species of endangered fish, a river that supports an entire region with regards to agriculture, recreation, and economy, and is arguably the central character in one of our country’s most unique and amazing National Monuments, the Yampa is as complete a river to protect as could possibly be imagined.

I hope if there is any place you put on your list to explore in the west, it is the Yampa River through Dinosaur National Monument. It is truly amazing. And I encourage you to gaze upon its khaki sandstone walls and juniper-dappled landscape, and reflect back upon the fights that happened here before our time, and the quest to keep this river flowing wild and free.

Paddling the Yampa River | Sinjin Eberle

Guest post by Lee Willbanks is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the St. Lawrence River.

Environmental considerations were not part of the planning process when the Moses-Saunders Hydropower Dam and shipping channel were built along the St. Lawrence River in the 1950s. As a result, outdated dam operations have caused significant losses to the Upper St. Lawrence River’s globally-significant biodiversity and habitat.

Impacts include a loss of wetland habitat and a decline in many fish species and nesting water birds. Black Tern, a state-listed endangered bird species that depends on a diverse marsh habitat, has declined by over 80 percent. Northern Pike, the top fish predator in coastal marshes, has declined by 70 percent. These species are indicators of ecosystem health, and show how far-reaching the dam’s impacts have been to the entire river environment.

Fortunately, a proposed regulation plan under consideration by the U.S. and Canadian governments, Plan 2014 [pdf], is designed to adjust the Moses-Saunders Hydropower Dam’s operations so as to work with nature.

It is time Secretary John Kerry and Foreign Affairs Minister Stéphane Dion listen to the over 22,500 expressions of citizen support as well as the 42 environmental, conservation and sportsmen organizations and local and regional businesses advocating for Plan 2014.

In April, American Rivers named the St. Lawrence River one of America’s Most Endangered Rivers®, shining a national spotlight on the threat outdated dam operations pose to imperiled fish, wildlife and local communities.

Both Save The River and American Rivers are focusing their collective attention on the only bi-national river to make the 2016 list. With your support, we can remove the St. Lawrence River from American Rivers’ annual list of America’s Most Endangered Rivers®.

Lee Willbanks on the St. Lawrence River

Lee Willbanks is the Upper St. Lawrence Riverkeeper and Executive Director of Save The River.

Save The River was formed in 1978 to protect and preserve the ecological integrity of the Upper St. Lawrence River through advocacy, education, and research.