Guest post by Congresswoman Elise Stefanik is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the St. Lawrence River.

In the North Country, we are fortunate to be surrounded by many ecological treasures. Protecting these gems for future generations is a job I take very seriously.

This is why I have been a strong advocate of Plan 2014 to better regulate our waters.

For the past 50 years, human-regulated water levels that were designed to benefit hydroelectric power and the shipping industry have significantly altered the natural processes of Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River, harming habitat diversity. American Rivers has even included the St. Lawrence on their annual list of America’s Most Endangered Rivers®.

Plan 2014 will better regulate water levels through the Moses-Saunders Power Dam as well as outline the conditions needed to change water levels and maintain the proper ecological balance. According to the International Joint Commission, “Plan 2014 will benefit ecosystem health, moderate extreme high and low levels, better maintain system-wide levels for navigation, frequently extend the recreational boating season and slightly increase hydropower production.”

Additionally, New York is the epicenter of invasive species, with more of these pests in each county than any other state in the country. These ecological predators threaten the health and beauty of our abundant natural habitats. In my lifetime, I have watched the detrimental effects that zebra mussels have had as they migrated into the waters of Lake Champlain.

Right now, the current outdated water level plan is wiping out habitats and destroying native species, which clears a path for invasives to take over and control these areas for themselves. Plan 2014 would return Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence to more natural levels and a normal hydrologic cycle, protecting our ecology and helping to preserve the long term health of the lake.

As we know in the North Country, our environment is our lifeblood; supporting this project is critical to our local economic growth in addition to good environmental policy. For instance, better regulating the water levels of the St. Lawrence will ensure that users– from boaters to commercial fisherman– can continue to enjoy the river. In addition, lowering the impact of invasive species will ensure that outdoor recreationalists can enjoy the river for decades to come. The Nature Conservancy estimates that Plan 2014 will result in an increase of $9.1 million in economic activity for New York and it has strong support from businesses and Chambers of Commerce across our region.

I have been working closely on this important issue with groups like Save The River. We are building support in the New York congressional delegation and speaking to the Governor’s office, our state senators, assemblymen and women, so they understand the broader economic importance of continuing to grow tourism and commerce in Northern New York.

Protecting our natural treasures cannot wait. The work done by the St. Lawrence River community has been steadfast, as for the last two decades they have worked together to see this new plan developed.

We must continue to build support for this critical plan to preserve our ecological gems for future generations.

Congresswoman Elise Stefanik

Congresswoman Elise Stefanik proudly represents New York’s 21st District in the House of Representatives where she is a Member of both the Armed Services Committee and the Committee on Education and the Workforce. Prior to winning her election to Congress, Congresswoman Stefanik worked at her family’s small business called Premium Plywood Products that was founded in Upstate New York over twenty years ago.

Today’s post is a guest blog co-authored by Dan Omasta, Director of River Restoration Adventures for Tomorrow, and Neal Schwieterman, who resides in Paonia, CO with his wife and daughter. He is a retired police officer and recently retired as Mayor of Paonia. He continues to inspire youth through kayaking and is looking to start his 3rd career. River Restoration Adventures for Tomorrow is a grant recipient of the Connecting Communities to Rivers Grant Program.

“How many of you have been rafting before?” was the question asked to the group of middle and high-school students eagerly standing along the banks of the lower Gunnison River just outside of Delta, Colorado. Only a few of the twenty-two kids nervously raised their hands.

That spring river trip was dedicated to getting local youth out on the water as part of an effort by American Rivers and River Restoration Adventures for Tomorrow (RRAFT) to connect communities to their watersheds. Not only did these students get a chance to float the muddy waters of the Gunnison for the first time, they also helped to map stands of invasive Russian Olive trees as part of an ongoing Bureau of Land Management initiative to improve the riparian ecosystem in that area. By providing youth with opportunities to explore and contribute to their local rivers, RRAFT and American Rivers aim to foster life-long watershed stewards.

As part of that trip, RRAFT also invited local outdoor industry professionals to work alongside the youth participants. This collaboration was intended to inspire future careers in the outdoor field and motivate the kids to dream big! There were several great professionals that joined our group, one of them being Neal Schwieterman, a former police officer dedicated to empowering youth through kayaking.

Neal moved from Ohio to Colorado in 1992 partly for the skiing and partly to get out of the canoe and into a kayak. During our trip, he explained that:

“I found a home in Golden, Colorado, where the local kayak club was in need of boat storage. I volunteered to lend a hand and got my first taste of how rivers and kayaking can impact our lives. As a police officer with the Jefferson County Sheriff’s Department, I had seen my fair share of tragedy and struggles within the community – including the Columbine High School Shooting in 1999.

Rivers have always been a space for me to find peace of mind and get in touch with the soul. They are a place to relax and heal. The Columbine tragedy changed the perspective I have on my life, reminded me how important family and community are, and made me recognize that I needed to do something to make sure that events like Columbine don’t happen again.”

Shortly after the Columbine High School shooting, Neal and his family moved to the Western Slope of Colorado where he joined the Paonia Police Department.

“I realized that I REALLY NEEDED to do all I could to make sure that shootings NEVER happened HERE. With my experience at the Kayak Club in Golden, I started the Paonia Kayak Club. We were a rag tag group in old school long boats and shabby wetsuits, but we were on the river. The High School had three days where we were able to get kids on the water at the end of the school year. After one of our spring break trips down the Colorado through Ruby-Horsethief, I asked one of the students if this was worthwhile; Katie (a former student of mine) answered, “YES! Because now I know how to do something the football players don’t.”

Her response highlighted the positive impact a river can have on a kid’s outlook. Connecting youth to their local rivers empowers them to move beyond their day-to-day perceptions of life in the classroom and enables them to grow through the unique challenges that our waterways provide. These kids are learning about safety, teamwork, and most importantly – that they can do anything they put their mind to. The club continues to thrive and to-date has taught almost 150 kids to kayak.

The new boaters have gravitated to younger ages, beyond just the high school students. Many that start boating may not move beyond Class II, but several have become solid Class IV boaters. One in particular, Mason, started as 10-year-old and continues to be Neal’s best paddling partner even as he enters his senior year at Montana State. “We have identical safety expectations and similar abilities, albeit at 21, his skills are rising and at 54, mine are likely not” Neal jokes. Kayaking has shown these students that they are capable of whatever they put their mind to; as one student exclaimed, “kayaking taught me I could do ANYTHING!”

When RRAFT took the high school kids out on the Gunnison River in May, outdoor professionals, including Neal, were a part of this transformation. Schwieterman sums it up perfectly when he explained:

“I teach kids to kayak and appreciate the river, but what they learn is self-confidence. That confidence is what I hope will continue to guide kids away from struggles and triggers that can result in the ever-too-common bullying and tragedies we see today. It is also something that youth will take with them for the rest of their life.”

Guest post by Dr. Caroly Shumway is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Merrimack River.

The Merrimack River has a long relationship with its people. Up to 12,000 years ago, Native Americans relied on the Merrimack for its abundant migratory fish runs. Then in the 1800’s, industrialists utilized the river for hydropower and to run textile mills. Anecdotally, it has been reported that there were so many salmon running the river in the 1800’s that one could walk across the river during a salmon run without getting one’s feet wet! Today, 600,000 people depend on the river for drinking water, including the six communities of Lowell, Lawrence, Tewksbury, Methuen, and Andover, in Massachusetts and Nashua, New Hampshire. Two more cities in New Hampshire, Manchester and Concord, plan to do so in the near future.

When I started as Executive Director of the Merrimack River Watershed Council in 2012, I met people with very different perceptions of the river. Older generations remembered the stench and pollution of the waters. Younger people, who never encountered the river when it was among the top ten most polluted in the country (as a result of that industrial legacy), have a different reaction. After chatting with some colleagues in a coffee store, a woman came up to me. “I love the Merrimack!” she exclaimed. She was a photographer, she said, and she offered her services for free if it would help the river.

Why we need everyone’s help on the river now

Today, the Merrimack watershed faces new threats. The watershed is largely forested by private land. Seventy-six percent of the land in this section of southern New Hampshire is privately-owned. This area is one of the fastest growing in the state. If the development was thoughtfully planned, it would not be a problem. Unfortunately, the development is largely unregulated and the associated sprawl has become a major issue for the health of the Merrimack watershed.

The trees and shrubs that line the river help protect our water quality. Acting as nature’s water filter, they (along with the microbes in the soil) help absorb pollution that otherwise would run into the river. The best, cheapest way to prevent such pollution is to protect at least one hundred feet of the naturally vegetated buffer along the length of the river. Unfortunately, few towns or cities in New England have this level of protection, and the State of New Hampshire has no regulatory buffer requirements.

Increased development pressure doesn’t just mean houses. It means associated strip malls and miles of pavement. It means lawns instead of trees. The added pavement and parking lot acreage cause increased runoff of sediment, heavy metals and oils from cars and nutrient pollution from lawn fertilizers. Such runoff pours from storm drains directly into the river without being treated.

Why does this matter?

600,000 people in the watershed, including two large environmental justice communities, depend on the river for drinking water. In addition, the river is considered one of the top three most important rivers on the East Coast for migratory fish; it is also important for birds and rare and endangered species. Nevertheless, increased nutrient levels have already caused the Merrimack River watershed to become the second greatest source of nutrients to the Gulf of Maine, on which many New England fisheries rely.

Here’s the thing. We know what will happen if the watershed is deforested. In the late 1800’s, deforestation in the watershed was rampant. Trees were being cut down left and right, as timber prices soared after the American Civil War. The loss of the trees changed the river’s flow, which impacted the textile mill owners who used the river’s power in their dams. In fact, one of the mill owners in Manchester helped to push for protection of the White Mountains, part of the headwaters of the watershed.

We also know today how important river buffers are. In 2013, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) reviewed the health of our rivers and streams nationwide. Over half of the country’s rivers and streams are in poor shape, and the condition of nearly 25 percent of degraded rivers can be attributed to lack of adequate river buffers. Sweeney and Newbold (2014) showed that, “Overall, buffers greater than or equal to 30 meters wide [i.e., nearly 100 feet] are needed to protect the physical, chemical and biological integrity of small streams.”

What needs to be done and how can you help? We are asking for federal assistance and funding from the EPA to create a bi-state integrated watershed team and plan. While this would be non-regulatory, it would help to provide funds for a watershed coordinator and facilitate an organized effort to protect critical lands, particularly next to the river and its tributaries, while we still can.

Caroly Shumway

Dr. Caroly Shumway is the outgoing Executive Director of the Merrimack River Watershed Council. Caroly has been the Executive Director since 2012. She has 25 years of experience in conservation and natural resource management, policy, and outreach in the U.S., Africa, and Asia. She is leaving MRWC to become the Chief Scientist for the U.S. Agency for International Development.

Today’s post is a guest blog from Roberta Salazar, Executive Director of Rivers and Birds. Based in Taos, New Mexico, Rivers and Birds provides experiential education and promotes conservation advocacy of our public lands to inspire Earth stewardship. Rivers and Birds is a grant recipient of the Connecting Communities to Rivers Grant Program.

Ask any visitor to Taos what feature impacted them most upon their arrival and you will likely hear about their first sight of the Rio Grande Gorge as they topped the hill nearing Taos. This dramatic geologic incision in the earth is the vessel that contains the upper Rio Grande River, a 74-mile stretch of pristine river and one of America’s first Wild and Scenic Rivers designated in 1968.

Unfortunately many Taos natives, including those from Taos Pueblo and local Hispanic villages, don’t often get the opportunity to experience the beauty of the Rio Grande. However, in May, Rivers & Birds collaborated with the National Outdoor Industry to introduce kids to this extraordinary river as part of the nation-wide celebration of the 100th anniversary of America’s National Parks and Monuments. With volunteer community members, we organized an effort to take economically-underserved fourth-graders into Rio Grande del Norte National Monument and the Rio Grande Wild and Scenic River for two days of adventure.

Enjoying the Rio Grande

May can be hot in Taos. Long hikes over rugged, dark volcanic rocks can be too much for people to enjoy the Wild and Scenic River area, but not for fourth-grade students! The students hiked from the trailhead 800 feet down to the edge of the river, where the roar and spray from a class VI rapid was impressive, and refreshing. Though the hikes were challenging, the students and parents were energized. One teacher exclaimed, “My kids are so happy about their hike. They have so much energy. It’s the adults that get worn out.”

Many students and parents had never visited the National Monument and Wild Rivers Recreation Area. The physical adventure into the volcanic gorge with its rushing whitewater, prehistoric petroglyphs, and wildlife was thrilling. Students said they couldn’t wait to return with their families. One fourth-grader, Zachary, said, “I want to come back with my family to play.” Jasmine another student exclaimed, “I’m going to bring my dad here. We will go fishing!” The parent chaperones were also enthusiastic. Brian MacCormack, an Iraq war veteran, and parent confided, “I wasn’t familiar with the Wild Rivers area. As a veteran, I have struggled to heal. What I have found most helpful for bringing a sense of peace back into my life is getting out in nature like this. I am going to bring my children back here for a camp out this summer.”

Rio Grande River

In addition to hiking through the National Monument and experiencing the river from the banks, the kids were also able to float the river. Cisco Guevara, owner of Los Rios Rivers Runners and a native New Mexican, provided the school raft trips. He sums up the outdoor celebration: “Kids being out in nature is great because of the connection they get, not only to the natural environment but to themselves. We are all a part of the natural environment.”

The Rio Grande is the ribbon that weaves together the various cultures of our diverse community from north to south – a deep connection that goes back hundreds of years. Rivers & Birds engineered this effort with strong community support so that diverse public school students with their families could experience Rio Grande del Norte National Monument and Wild and Scenic River.

Good intentions do not always lead to good ideas.

This was made evident when the Alaska Power Authority proposed to build a 700-foot-high dam on the Susitna River in Alaska.

Fortunately, the Governor of Alaska, has recognized that continuing to spend money on this boondoggle project is not a great idea and has directed the Authority to shut down the project. So far, the state has spent $180 million toward studies for the project to get a federal license to generate hydropower at the dam site.

The proposed Watana dam would be located 90 miles upstream from Talkeetna and would be one of the tallest dams in the US. The dam would directly affect 233 miles of the mainstem Susitna River and indirectly about 1300 miles of its tributaries and would devastate all five species of wild Alaska salmon as well as impact caribou, bear, moose, and migratory birds.

The project with a price tag of $4.5 billion is a false solution to Alaska’s impending energy problems. An independent analysis done in 2012 stated that:

“[a] better alternative to providing long-term, affordable, stably priced energy is for the state to finance, explore and produce the Cook Inlet Basin gas resource it already owns. For considerably less investment than Susitna, the state can meet the current Railbelt demand for electric power and space heating for the next 100 years with stable prices- one-third the price of a Susitna kilowatt hour in fact- and with less environmental impact than a Susitna power dam.”

Deriving energy from natural gas from Cook Inlet is a more cost-effective alternative and requires the least capital investment, yet producing the greatest long-term economic benefit to the regional economy with the least environmental and social impact. Although it’s not clear what the Governor plans to do in terms of exploring other energy options, it is heartening to know that he has killed an ill-conceived project thereby protecting one of the last free-flowing rivers belonging to our nation.

Moving water creates magic. It happens in places where the endless force of current marries with the land in stunning and awe-inspiring ways, and in places where people who love rivers can connect with their passions for fishing, paddling, or being in a gorgeous, natural area.

One such place is the Gunnison Gorge National Conservation Area, just downstream from the Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park in western Colorado. Here, the Gunnison River has cut a canyon so deep and steep that after hiking over a mile down into it, you are in another world – one where some of the oldest rock on the planet has given way to the power and persistence of rushing water. It seems fitting that the words “gorgeous” and “gorge” come together here.

Having heard high praise for the Gorge and its fishing, my son and I took a 3-day float trip last month with the fantastic staff of Black Canyon Anglers. We were hoping to be there for the famous salmon fly hatch that brings massive trout to the surface to engorge themselves on these huge bugs. We were a little late for the hatch, but thanks to our guide, Angus Drummond, we had a wonderful time catching our share of good-sized Brown trout. But beyond that, we became awestruck floating between the tight canyon walls, sleeping under the stars to watch the Milky Way cross the sky above the Gorge’s rim, swimming under hidden waterfalls that defy the arid heat, shooting the many Class III rapids, and being taken in by all that the Gorge offered. All of these experiences were thanks to the river as it tirelessly pushes downstream. And did I say that the fishing was good, too? Magic.

Looking Glass Falls

A second place to find this magic is Pisgah National Forest in Transylvania County in the North Carolina mountains – home to 250 waterfalls. After I had returned from Colorado, my wife had planned a trip with our daughters to see these wonderful sites. In the span of a few days, we visited DuPont Falls, Twin Falls, Sliding Rock Falls, Skinny Dip Falls, and Looking Glass Falls. Some were crowded because of the holiday weekend, but others we had to ourselves. At all of them, you could see the beauty of shining water taking flight from rocks that are as old as time. To sit in the cavern behind a waterfall, to swim against the current that comes from the stream’s 100-foot fall, and to feel the cool mist from the fall’s spray is to connect with a phenomenon that has been here for eons. Magic.

Since American Rivers is in the business of protecting and restoring rivers as the national treasures they are, it must be said that we can all visit these places because of the foresight of those who worked to protect them. We continue to follow that path with a goal to protect another 5,000 miles of Wild and Scenic Rivers in celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, so that many more of these magical places will be protected forever.

We would love to hear about your favorite places of river magic! Share them here in the comments, on our story pages or on social media with the hashtag #WeAreRivers.

Guest post by Ron Thomson is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the St. Lawrence River.

As the owner of Uncle Sam Boat Tours, I have directly experienced the damage poor water level management has had on the environment and area businesses.

The economy of the St. Lawrence River and Lake Ontario region depend on the health and beauty of the lake and river and their ecosystems. Moving toward more natural water flows in these bodies of water will not only improve the environment, it will also provide substantial economic and shoreline benefits.

Let’s look at the economic case for a revised approach to water levels.

First, and closest to my heart, healthier lake and river wetlands will support stronger populations of native fish and wildlife, improving the area’s hunting, angling, and wildlife-viewing opportunities. The Nature Conservancy estimates economic benefits, just from improved wildlife recreation, of $4.0 million to $9.1 million per year.

Second, the real and direct economic benefits of Plan 2014 do not stop with recreation. Hydro-electricity production will increase by $5.3 million a year under Plan 2014. This low-cost power supports jobs in New York State. Furthermore, compared to the cost of protecting properties from erosion and flooding under unregulated conditions, Plan 2014 is estimated to save property owners on the lake $23.0 million per year. This may be $2.2 million less than current savings, but the figure remains very significant.

Third, and more generally, investing in our environment leads to economic advantages. A 2007 cost-benefit analysis by the Brookings Institution demonstrated that each dollar of restoration brings two dollars of benefits to the economy of the Great Lakes region.

The St. Lawrence River and Lake Ontario are part of the larger Great Lakes System, which is the world’s largest freshwater ecosystem and constitutes an irreplaceable international treasure. Plan 2014 will enhance this ecosystem and improve the economy at the same time. Secretary Kerry and Minister Dion need to implement Plan 2014 today.

Uncle Sam Boat Tours

Ron Thomson is the Owner of Uncle Sam Boat Tours. Uncle Sam has been providing scenic cruises of the Thousand Islands for over 85 years from its downtown Alexandria Bay, NY location opposite Boldt Castle.

Guest post by David Klein is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the St. Lawrence River.

Previous posts in this blog series have documented the severe impacts to the St. Lawrence River and Lake Ontario resulting from the current regulation plan – a plan that has reduced the natural rhythm of water flows and levels to the point of causing extensive damage to the 64,000 acres of wetlands that ring the coastline of the lake and river. It’s well-established that wetlands offer considerable benefits for people and nature, including flood protection, pollution reduction and outdoor recreational opportunities. These benefits bring considerable economic value to our communities.

What would happen to New York’s regional economy if we could restore the health of the coastal wetlands of Lake Ontario/St. Lawrence (LOSL), and the services these wetlands provide?

Fortunately, we have a clear answer.

The International Joint Commission (IJC) has proposed a new plan – Plan 2014 – for regulating the water flows of the St. Lawrence and levels of Lake Ontario that will accomplish this wetland restoration at an ecosystem scale.

So, what are the exact economic benefits of Plan 2014?

Using a set of predictive models developed by Colorado State University to estimate additional days of wildlife-related activity and the increased economic value of outdoor recreation (hunting, fishing, wildlife viewing) that will result from Plan 2014, The Nature Conservancy predicts the implementation of this plan will result in $9.1 million in increased net economic value in New York State, every year.

To arrive at this figure, we estimate approximately half of the wetlands degraded by the current regulation plan– 32,000 acres – are located in New York, and adopt a very conservative approach to quantifying the amount of wetland improvement. The IJC analyses forecast a minimum 17 percent increase in the ability of LOSL wetlands to support the plant and animal diversity of healthy wetlands. Using this increase as a guide, New York State will see:

- $2.6 to $7.7 million per year―the value associated with a 17 percent improvement in function of wetlands. This represents the net economic value from the additional fishing, hunting and bird-watching opportunities.

- $1.4 million per year―the increase in economic input that participants in outdoor activities will contribute in additional direct trip expenses to the region’s economy each year.

These values do not represent the total benefits from restored wetlands under Plan 2014, but demonstrate the economic impacts of improvements to a single service provided by wetlands. By increasing the overall health of coastal wetlands, Plan 2014 will restore these benefits (and more), enhance the resiliency of the shoreline in a changing climate, and provide greater economic opportunities for all people in the region, including property owners and shoreline communities.

What if we just restored wetlands without Plan 2014?

Another way of assessing the value of Plan 2014 is to compute the estimated savings, or what it would cost New York taxpayers to manually restore each of the 32,000 acres of coastal wetlands.

Based on costs of recent wetland restoration projects, the expense is staggering.

- $54 million—the estimated cost to manually restore 32,000 acres of coastal wetlands; however, without restoring the natural variation in water levels and flows, which shapes and maintains coastal wetlands, this huge price tag would not result in lasting improvement. Plan 2014, by partially restoring natural variation while controlling extreme high and low water levels, will perform this gigantic restoration for free, with permanent benefits.

What should we do?

The environmental and economic cost of the current regulation plan is simply too high. That is why over 50 outdoor and environmental organizations, dozens of businesses, 23 towns and counties, and 23,000 New Yorkers now call on Secretary Kerry and Minister Dion to implement Plan 2014 without further delay.

David Klein is a Senior Field Representative with The Nature Conservancy. David has worked for the Conservancy for 23 years. He focuses on conservation issues relating to the watershed, coastline and open waters of Lake Ontario.

If you live in Atlanta, you’ve probably heard that the Braves are leaving Turner Field. Whatever your feelings may be about the Braves, for the local residents in this low-income community of color, this move presents a rare opportunity. An opportunity to reduce the persistent flooding; an opportunity to get a grocery store; an opportunity for translating a shared vision into action; and an opportunity to create a neighborhood that equitably serves the residents for the first time since the 1940’s.

Check out this article from the coalition of residents known as the Turner Field Community Benefits Coalition (TFCBC) to learn more about the history of the area.

Despite this challenging history, there has been cautious optimism around the recent Turner Field Stadium Neighborhoods Livable Centers Initiative (LCI), a community visioning process for the future of the area. The LCI has involved hundreds of residents and focused on transportation, urban amenities, density, stormwater, the environment, and other issues of importance. Parallel to the LCI, the TFCBC published a survey of almost 1,000 residents. Top answers to a primary question, “The New Development Should…” included: “Manage Stormwater” (#1), “Be Environmentally Friendly” (#4), “Create More Job Opportunities” (#5), and “Include Public Parks/Green Space” (#6).

After reviewing these results with residents, we at American Rivers considered how the benefits of green stormwater infrastructure (GSI) could address several of the community’s top priorities. So we offered to assist both the TFCBC and the LCI in crafting robust, yet realistic recommendations for the implementation of GSI for the redevelopment, as well as for the adjacent interstate highways—a major source of runoff. After attending multiple community meetings and listening to what people were asking for, we developed recommendations to capture the first 1.8” of rain from each storm wherever possible, totaling about 3.6 million gallons per storm. Then we backed these recommendations up with two feasibility assessments, which rely primarily on rainwater harvesting, permeable pavement, and bioretention. The draft LCI Plan, including American Rivers’ recommendations, is now available for review and comment here.

The most recent step in turning these recommendations into reality has been working with ECO-Action to train local residents to become advocates for GSI. By investing in local capacity, we hope that there will be voices for sustainable water management in the community for decades to come.

Guest post by Matt Norton is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Boundary Waters.

Paddling against the current is equal parts exhilarating and challenging. The continued effort to protect the Boundary Waters Wilderness is often exhilarating and challenging too.

This 1.1 million acre Wilderness in northeastern Minnesota is a mosaic landscape composed of different forest types, wetlands, and streams, shot-through with a vast network of interconnected lakes and rivers. The scenery is beautiful, there’s lots of wildlife one rarely sees elsewhere, and the fishing and hunting opportunities are the finest I’ve ever enjoyed. Some of my most cherished memories are of time spent in the Boundary Waters Wilderness with family and friends.

The Wilderness faces a great threat from Twin Metals, a mining company owned by Chilean mining giant Antofagasta, which proposes to build a sulfide-ore copper mining operation just outside its borders.

American Rivers recognized this threat by naming the Kawishiwi River, which is on the path of pollution from the proposed mine, as one of America’s Most Endangered Rivers® in 2013. American Rivers is working with the Campaign to Save the Boundary Waters to protect the area.

The challenge we face right now is to urge the U.S. Forest Service not to renew Twin Metals’ expired federal mineral leases. Now is the time to act, as the Forest Service is taking public input through July 20, 2016.

These mineral leases are more than 50 years old, and have never undergone environmental review, as they were issued before passage of the federal Clean Water Act and National Environmental Policy Act. Today, we understand so much more about the risks to nearby waterways, and we are at a critical crossroads in the future of these rivers and lakes.

Boundary Waters

According to a statewide poll released in early March 2016, 67 percent of Minnesotans oppose, “sulfide-ore copper mines on the edge of the Boundary Waters Wilderness.” Keep in mind that this type of mining has never been done in Minnesota, and has never been done anywhere in the world without polluting.

Protecting the Boundary Waters is not something we can do alone. The Bureau of Land Management ultimately holds the authority to renew or deny these leases, but they recently asked the U.S. Forest Service if it would grant or withhold consent for renewal of the leases. Saying the agency is “deeply concerned,” the U.S. Forest Service announced on June 13 that it is “considering withholding consent for lease renewal” of Twin Metals’ request to renew two 50-year-old, expired federal mineral leases on the edge of the Boundary Waters Wilderness.

Anyone who believes in the value of clean water, the outdoor industry, and the endless power of the Wilderness should stand with us and partners like American Rivers on this issue. Join us at the Forest Service listening session in Duluth on July 13 to tell the Forest Service to protect the Boundary Waters. Your voice counts.

Matt Norton

Matt Norton is the Policy Director at Save the Boundary Waters. The Campaign to Save the Boundary Waters is leading the effort to ensure permanent protection for the Boundary Waters Wilderness, America’s most visited Wilderness and Minnesota’s crown jewel, from proposed sulfide-ore copper mining.

I just returned from a fantastic trip with OARS Dories down Idaho’s Wild and Scenic Main Salmon River. OARS, along with NRS and other partners, are teaming up with American Rivers to celebrate the upcoming 50th anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. This trip was part of our effort to build momentum and collect stories, photos and video for the campaign.

It was a dory trip – the first for OARS in Idaho in roughly 14 years – and a personal first for me. Ever since reading Kevin Fedarko’s The Emerald Mile, I’ve wanted to experience a dory. Describing this beautiful wooden boat in the Grand Canyon Kevin writes:

“Unlike the rafts and the motor rigs or the generations of wooden boats that had proceeded her, she didn’t plow piggishly through the waves, but instead seemed to dance over them. As she planed across the surface of the river, breaking the water into a series of interlocked, V-shaped ripples, she achieved a bewitching visual alchemy, almost if she were suspended partly on the surface of the river and – through some ineffable trick of her rocker, her rake, and the magic of her radiance – suspended partly on the air itself.”

One of my most vivid memories from our trip is sitting in the front of the dory named Quartz Creek and charging head-on into a rapid, with a beautiful gleaming green wave rising up in front of us. We danced right through, our guide Amber making it look easy.

Amber, who was recently profiled in the Yeti film In Current, gave up a family reunion to guide on this trip. She told her mom that it just wouldn’t be right if the first dory trip in Idaho only had men as guides. This trip needed a female guide, and Amber was it.

River Guide Amber Shannon

Wild and Scenic, the highest level of protection a river can have in our country, in 1980. That means it will always be preserved in its natural state, and dams and other harmful water projects are prohibited.

There’s a certain magic that comes with wild rivers. For me, on this Salmon trip, it was in the moments –

Baking in the hot canyon sun, then plunging into the cold clean river, the most refreshing feeling in the world.

Leaning back in the boat to watch two osprey soaring overhead as clouds gathered over the confluence with the South Fork.

Standing barefoot in cold sand in the morning, drinking hot coffee and listening to a canyon wren calling across the river.

Finding the cherry tree at the Frank Lantz cabin that I remembered from a trip with friends ten years ago.

Pulling up to the beach with the hot springs and watching swirls of butterflies filling the air.

Picking thimbleberries along the creek, hiking up to the cool and shady Pacific Yew grove.

And at Alder Creek Rapid, watching the other dories disappear over the drop then riding through the waves, light as a feather.

Main Salmon River

Why do we need wild rivers? Why are places like the Main Salmon so special? The reasons are as practical as clean water, as important as heritage, as personal as love.

That is why, with the 50th anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act coming in 2018, American Rivers is launching an effort to protect 5,000 new miles of rivers. So that more people can experience this magic, and we can preserve it for our children.

I’m so grateful to our fantastic OARS guides Hud, Amber, Barry, Jake, Chris and Sarah for making this such a memorable trip, and to OARS for being a company so dedicated to river conservation. Being on the Salmon has made me more fired up than ever to protect more Wild and Scenic Rivers. We can’t wait to share more about this exciting campaign.

Guest post by Erin Crotty is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the St. Lawrence River.

In 2012, Audubon New York, the state program of the National Audubon Society representing 27 local Chapters and 50,000 members in New York State, submitted comments from 554 people from Audubon’s network to the International Joint Commission in support of Plan 2014. Audubon New York continues to be fully supportive of Plan 2014 which achieves a balance of benefits for all interests by simply restoring some of the natural fluctuations in water levels to St. Lawrence River and Lake Ontario. Today, I would like to focus on one element that makes Plan 2014 so important to Audubon— the impact on endangered and threatened bird species.

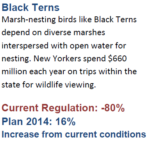

Marsh-nesting birds like Black Terns depend on diverse marshes interspersed with open water for nesting. Since the current regulation plan was put in place, Black Tern populations have decreased by an unfathomable 80 percent.

Black Tern Statistics

The enactment of Plan 2014 will have enormous benefits and is projected to increase populations of this New York State-listed endangered species by 16 percent.

By restoring the natural flow and fluctuation of water levels, promoting increased wetland diversity, and restoring natural cycles, Plan 2014 will improve habitat quality for other key bird species, including Least Bitterns (a New York State listed threatened species), Virginia Rails, Yellow Rails (a red listed species on the Audubon Watchlist), and King Rails (a New York State threatened species and yellow listed on the Audubon Watchlist).

Furthermore, the restoration provided by Plan 2014 would greatly benefit the economic and cultural identity of upstate New York and the entire Great Lakes region as New Yorkers spend $660 million each year on trips within the state for wildlife viewing. As many efforts are being made to address the serious declines of these important bird species, implementing Plan 2014 now would be an important, cost-effective step toward their conservation goals.

To ensure these significant investments are not wasted and balance is restored to the regulation of water levels, Audubon New York strongly urges Secretary Kerry and Minister Dion to implement Plan 2104 without further delay.

Erin Crotty is the Executive Director of Audubon New York. Audubon New York is the state’s leading voice for the conservation and protection of natural resources for birds. Integrating science, conservation, policy and education, Audubon’s mission is to conserve and restore natural ecosystems, focusing on birds, other wildlife, and their habitats for the benefit of humanity and the earth’s biological diversity.