I’ve never been so excited to visit a place famous for rain as I was last week in Seattle, learning about green stormwater infrastructure (GSI) from some of the nation’s leaders. If you’re scratching your head about “GSI”, just know that it’s an approach to wet weather that mimics nature to soak up, evaporate, transpire, or recycle stormwater. In short, GSI means catching the rain with plants, not pipes.

GSI instructional placards in Seattle | Jeremy Diner

I was surprised to learn that Metro Atlanta gets about 30% more rain than Metro Seattle, is 40% bigger, has 50% more people, and in 2015, Atlanta even had more wet days than Seattle. So what makes Seattle national leaders when arguably, we have a bigger stormwater problem around Atlanta? That’s what we went to learn.

American Rivers co-sponsored this peer exchange to Seattle, which included our partners at Clayton County Water Authority, their consultants from CH2M, and the Chief Operating Officer from the county. Our goal was to learn strategies and techniques for how to reduce water pollution and flooding with GSI, while simultaneously gaining multiple quality of life and economic benefits.

With over 15 years of experience, Seattle has a lot of success stories. One thing that was immediately clear was the strength of their partnerships. This included partnerships across multiple government departments (with a focus on transportation), as well as extensive partnerships which extend into the non-profit, corporate, and public realms. They also have an iconic water body to rally around protecting: the Puget Sound. While Clayton County’s Flint River may not be as famous as the Puget Sound, it’s certainly a critical Georgian resource, worthy of protection, respect, and long weekends spent paddling.

Group shot of the exchange participants | Lauren Chamblin, CH2M

Another success story is Seattle’s willingness to talk about their failures and lessons learned. It’s not easy to embrace failures, but the rest of us really appreciate not having to make the same mistakes. The main issues we discussed were related to rushing, community engagement, and the equitable distribution of benefits.

At the end of the day, my biggest takeaway was that implementing GSI isn’t rocket science. If there is: 1) political will, 2) decent funding, 3) good relationships across departments, and 4) effective community engagement, then this should be a lot easier than most of the things our government does every day. American Rivers looks forward to supporting Clayton County Water Authority’s effort to green the county, so that we may improve quality of life for residents, grow the local economy, and protect the streams and rivers upon which we rely.

Guest post by Charles Scribner spotlighting the Black Warrior River.

Updated September 8, 2016:

Southern Environmental Law Center, Black Warrior Riverkeeper, and Public Justice sued Drummond Company for violations at its Maxine Mine site, an abandoned underground coal mine located on the banks of the Locust Fork of the Black Warrior River near Praco, Alabama.

Though mining at Maxine Mine ceased in the 1980s, acid mine drainage has been illegally discharging from the site into the Locust Fork through surface water runoff and seeps from the underground mine for years. The site also presents a substantial imminent harm to human health and the environment due to the storage of tons of mining waste on a bluff above the Locust Fork. Besides being a continuous source of acid mine drainage, the mining waste has completely filled a tributary of the Locust Fork.

The site currently consists of underground mine works, surface piles of mining waste, and a system of man-made drainage ditches and earthen dams used to create sediment basins for runoff from the waste piles. The basins are continuously leaking polluted water and the dams are holding acidic coal mine drainage and mining waste. The main dam by the river is deteriorating and could potentially breach, resulting in a large release of pollutants into the Locust Fork, a primary tributary of the Black Warrior River and a popular area for fishing, boating and other forms of outdoor recreation.

The Maxine Mine site is one of the worst of hundreds of abandoned mines in the Black Warrior basin, many of which continue to degrade streams and contaminate groundwater with unpermitted discharges containing high levels of sediment, heavy metals such as iron and aluminum, and other pollutants.

To address the ongoing pollution and storage of coal mine waste on the Locust Fork, the groups are seeking removal of the mining waste, excavation and/or remediation of contaminated streams, and any other appropriate measures by Drummond to immediately stop all illegal discharges at the site.

As outlined in the notice letter, the groups’ claims include violations of the Clean Water Act through illegal, ongoing discharges of pollutants into the Locust Fork and its tributaries, illegal stream filling, and violations of the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act for improper management of solid wastes.

It is important to note that Drummond Company is the same company who proposed the Shepherd Bend Mine highlighted in American Rivers’ annual report on America’s Most Endangered Rivers® of 2013. Drummond has withdrawn their Shepherd Bend permits, however, we don’t know if that withdrawal is permanent.

Charles Scribner

Charles Scribner is the Executive Director of Black Warrior Riverkeeper. Black Warrior Riverkeeper is a citizen-based nonprofit organization dedicated to improving water quality, habitat, recreation, and public health throughout the Black Warrior River watershed.

Guest post by Guido Rahr is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Smith River.

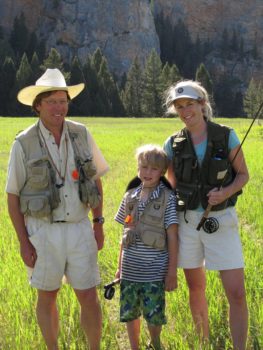

Rahr family on the Smith River.

Our family has had a ranch on the Smith River for almost 40 years. It is nestled in a broad valley, perched 800 feet above the river. From the edge of the canyon we can see the Smith far below: clear rifles gliding over yellow rocks and deep blue corner pools where the river has cut through hundreds of millions of years of ancient marine sediments. No painter of imaginary landscapes could describe a more beautiful tapestry of clear water, golden meadows, forests of Douglas Fir and limber pine — all framed by towering cliffs of cream and rust colored limestone.

The Smith River canyon is our place on the planet. It is where we come and where we will go. It is where we the different generations of our family come together, where we raise our children, teach them to flyfish for trout in the summer, and hunt deer and elk in the fall. My wife Lee and I were married on the meadow above the river, and my father and mother are buried there.

I am a landowner on the Smith and I also protect rivers for a living. My organization, Wild Salmon Center, gives me a front row seat on rivers that have been lost – and those which may be next. Gold and copper mines are our worst nightmare. We and our partners are now fighting mines in Bristol Bay Alaska and the Russian Far East. When my family learned of the Canadian mining company Tintina’s proposed mine in the headwaters of the Smith River, it hit close to home. Way too close.

Smith River, MT

There are many ways to destroy a river, but few are as pernicious as placing a hard rock mine in the headwaters. These type of mines often generate acid mine discharge, which shifts the delicate chemistry of rivers and undermines the very building blocks of aquatic life. What makes these kind of mines so dangerous is that the damage can be permanent. The threat of acid mine drainage or the catastrophic failure of a tailings pond never goes away. It can happen while the mine is in operation, or fifty years later. Witness the tailings dam failure of the Mount Polley mine in British Columbia in 2014, or the failure of the Gold King Mine in the headwaters of the Animas River in Colorado in 2015.

Anyone who has a commitment to a place of beauty and family history will fight to protect it. Mining companies always say there is no risk, that they are employing the best technology, that the community needs jobs. But in the end, the company will harvest its profits, then they will leave, and the jobs will dry up. But the mine and its reservoir of toxic chemicals will never go away. It will remain hidden far upstream, out of sight, hanging like the sword of Damocles, perched above us and our beautiful river, threatening everything out family holds sacred. Of course we and our neighbors on the Smith will fight the mine. It is an obligation that comes with the land.

Guido Rahr is the President and CEO of the Wild Salmon Center in Portland, Oregon. His family has had a ranch on the Smith River for 40 years.

On Monday, a member of the Navajo Nation Council submitted legislation that would authorize $65 million to start construction of the Grand Canyon Escalade. This project is a massive proposed resort development on the east rim of the Grand Canyon. The site itself is within the western Navajo Nation, on the border of Grand Canyon National Park, and above one of the most sacred sites in Native American culture – the confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado Rivers.

But how could this happen, when the sitting President of the Navajo Nation, Russell Begaye, has stated his outright opposition to the project? Let’s go through the details.

Tribal Government

Like the United States Government, the Navajo Nation has an Executive Branch (President’s office), and a Legislative Branch (like our US House and Senate). But in the Navajo government, there is only one legislative body, the Navajo Nation Council (like a combination of our House and Senate). A bill is introduced into the Navajo Nation Council, then if approved it goes to the President’s desk to be signed into law or vetoed.

Could the Escalade legislation pass?

Yes. Under tribal law, if the Council has enough votes to pass, it could over-ride a veto from the President’s office, with a two-thirds majority. There are 23 members of the Navajo Nation council, and to be “veto-proof” the bill would have to have 16 supporters. It is hard to know how many votes the bill currently has, but it is going to be close regardless.

Is this really urgent?

Yes. Under Navajo law, there is only a 5-day public comment period, which started Monday, August 29. The comment period (and time when your comments would be filed into the official record) ends September 3rd. If you care about the canyon, you need to speak up now.

How are we working with the Navajo people directly?

American Rivers is collaborating with the Flagstaff-based organization, Grand Canyon Trust, as well as the local, Navajo organization Save the Confluence. The Save the Confluence group is an on-the-ground, Navajo-led grassroots organization working within the Navajo Nation to oppose the project. Our three organizations collaborated extensively when we listed the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon as America’s Most Endangered River in 2015, and we continue to work closely together today.

View from the Colorado River. The gondola would extend down from the point upper left on the rim to lower right by the river, 1.4 miles total. | Sinjin Eberle

How could they build this? Isn’t inside the Grand Canyon National Park land?

Yes and no. The current interpretation is that the National Park service boundary includes the Colorado River, up to the high-water mark. The Navajo Nation boundary extends from the east rim of the canyon, down to that high-water mark line. The developers have proposed that there would be a resort development on the east rim, and terminate down in the canyon just above the high-water boundary line, connected by a 1.4-mile long gondola, all on the Navajo Reservation lands. The development would permanently impact the experience of park visitors and boaters. What is now a wild part of the landscape would become industrialized and crowded.

What about the confluence? Isn’t it sacred?

The confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado rivers is considered sacred by a number of tribes, including the Navajo. The Navajo do consider the confluence a place of deep spiritual significance, and the Hopi, Paiute, Zuni and other tribes and pueblos revere this place as well. As such, the Intertribal Council unanimously opposed this project in 2015 based on these values.

Exactly HOW could they build it?

That is a good question, since the area is extremely steep, rugged, and remote. Think about it – how would you get equipment staged to build a project like this? How do you get bulldozers and cranes and other heavy equipment into an area like this? A helicopter could not land there, since the only flat spot is in the National Park, which would never allow this. Whatever the developers are thinking, there would be impacts to the river and surrounding lands.

This view depicts where the lower development would sit. Construction equipment would have to build a lower gondola station, restaurant, restroom facility and elevated walkways here. Confluence with the Little Colorado River is seen in the background. | Sinjin Eberle

Don’t the Navajo need economic development?

Absolutely, and one of the main objections to this project is on an economic basis. The developers have stated that the project would create 3,500 jobs, but that figure has been argued for some time. The likely construction and infrastructure jobs would overwhelmingly come from outside the reservation, as would most of white collar jobs to run the resort. Some jobs, certainly, could be held by Navajo people, but all 3,500? Not likely.

The other argument is about revenue. Revenues from the resort to the Navajo people start at a mere 8% of the profit, and only increases as more and more people pay to ride the gondola, and tops out at 18% (assuming at least 2 million people pay to ride the gondola per year). Consider for a moment that the main Grand Canyon National Park saw its biggest year ever in 2015, with 5.5 million visitors – would 2 million people ever visit this resort destination 28 miles from highway 89? And how many of them would actually pay (upwards of $40-50 each) to ride the gondola?

This is a really bad deal for the Navajo people, especially those who live in the local area, as the Bodaway Gap chapter would get none of the tax revenue from the project, as well as the Nation being required to pay the $65-million dollar start-up bill to even get the project going.

But, what about people who can’t hike to the bottom of the canyon? Don’t they deserve to experience it as well?

Certainly, and Grand Canyon National Park already provides a world-class visitor experience today. Everyone can experience the canyon in their own way already – you can hike it, you can float it, you can ride a mule, and you can fly over it. And maybe most importantly, anyone can come to the rim of the canyon, sit in the quiet contemplation, and enjoy the view. Smell the air. Watch a raven glide overhead. The Grand Canyon belongs to all of us, for all time, and it should not be diminished..

So what can be done?

Most urgently, sign the petition, and then stay tuned as this saga continues to develop. There will invariably be more ways that your voice can be heard. Thank you for standing up for the Grand Canyon.

Guest post by Jim Klug is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Smith River.

There is no doubt that Montana is the epicenter for great fishing, bountiful access and healthy rivers in the U.S. West. While Montana is home to dozens of world-class rivers and fisheries, there is one river that enjoys a very special place in the hearts and minds of all who have been lucky enough to experience it first-hand – the Smith.

Montana’s Smith River offers anglers and river enthusiasts the opportunity to experience one of the last true wilderness river floats found anywhere in the lower 48 states. This 60-mile float flows through a remote and largely pristine canyon offering some of the most incredible scenery found anywhere in the Northern Rockies. Traffic is limited to non-motorized watercraft, and multi-day-float permits are limited and hard to come by. Most permits are awarded each year through a public lottery system, where roughly one in eight applicants are lucky enough to draw a launch permit. The rest of the permits are allocated to a small number of long-time outfitters who make it possible for clients to book the Smith with fully outfitted and guided packages. Many Montana residents look forward to our Smith trips every spring, and applying for the annual lottery has become as much of a seasonal tradition as the purchase of our annual fishing license or the first launch of the drift boat each spring.

Rafting on Montana’s Smith River

I made my first trip on the Smith River more than 15 years ago, and ever since that time, I’ve looked forward to my annual pilgrimage down the canyon. Over the years, I have made this trip with my wife and children, with long-time clients, and with countless friends. Memories made on this river are as special as they are irreplaceable.

Montanans are now being told that Tintina Resources – a small, foreign-owned start-up – intends to open and operate a massive copper mine at the headwaters of the Smith River on the banks of Sheep Creek. The Smith and its tributaries (including Sheep Creek) provide crucial habitats and spawning grounds for wild trout. Many of these fish travel more than 200 miles round-trip from the Missouri River to spawn in the Sheep Creek drainage, which comprises more than half of the tributary spawning area for rainbows, browns and other trout in the Smith River system. Sheep Creek is integral to the health and spawning populations of both the Smith River and the neighboring Missouri River.

Montana economists conservatively estimate that fishing on the Smith alone contributes more than $10 million to the state’s economy each year. This is a remarkable contribution given the short Smith River floating season, which typically runs from May through late July. Locally, fishing and recreational traffic on the Smith directly supports shuttle services, river-guiding companies, hotels, restaurants and all types of mom-and-pop retailers. For ranching families up and down the valley, water from the Smith irrigates thousands of acres of crops and is truly the lifeblood for these rural communities.

Tintina Resources is proposing a mine that would drop below the water table, creating a situation where they would have to constantly pump water out of the mine to keep it from flooding. This large-scale pumping of groundwater could dry up critical tributaries, harm resident trout and reduce spawning habitat. In addition, these discharges will include heavy metals, nitrates and arsenic, which will no doubt have a harmful effect on the immediate environment and of course on area waters.

Smith River, MT

Pat Clayton fisheyeguyphotography.com

Tintina tells us that they know what they are doing, but in truth, they are a small, foreign startup company that has never before operated a mine. They tell us that the mine will be good for locals and bring much-needed jobs to the area, yet the locals hired by the company to make promises to Montanans are low-level employees and not decision makers. They have little control over important decisions such as investment in environmental protections, community involvement or important employee safeguards. The president and CEO of Tintina is an Australian. The rest of the board is comprised of a Canadian, an Australian and two New Yorkers. None of them have ever before done business in Montana.

Montanans have heard Tintina’s story many times over. Mining companies come to the state promising to be responsible by employing new technologies. The end results, however, are almost always the same: cut-and-run exit strategies, a polluted after-math, and taxpayer-funded cleanups.

As a life-long angler and someone whose livelihood and income depend on healthy fisheries, clean water and sportsman’s access, I obviously care deeply about the condition and state of our state’s rivers. That said, I am not anti-mining any more than I am anti-timber, anti-agriculture or anti-oil or gas. Montana has a long history and a well-defined legacy of providing bountiful resources to all types of extractive industries, and these resources have certainly helped economic development in our state and country. I believe that while there are places in our state where mining makes sense, the headwaters of Sheep Creek and the Smith River are not one of those places.

Jim Klug

Jim Klug is the Director of Operations at Yellow Dog Flyfishing Adventures. Yellow Dog Flyfishing Adventures is a hands-on, specialty travel and destination angling company based out of Bozeman, Montana.

My friend and colleague Sinjin Eberle and I have a debate about National Parks. He’s a westerner, at home in the great expanses of the west, always in awe of the magnificent landscapes, the rushing rivers, the deafening quiet, and the humbling topography of Zion, Dinosaur, or the Grand Canyon.

Well, ok he has a point. But I’m here to speak for the east.

We’ve got some natural beauty in our National Parks here: the first rays of sunlight to strike America every day land upon Cadillac Mountain in Acadia National Park. Dolphins frolicking at dusk along Cape Hatteras National Seashore is something you can’t see in the Southwest. And I know my friends in South Carolina will argue that Congaree National Park has some of the coolest flora and fauna this side of, well, anywhere.

Even with all that, there’s a different kind of majesty that National Parks protect, preserve, and share, and that’s history. As Charles Kuralt said, “America is a great story, and there is a river on every page of it.” So I’m here to take you on a tour of just a few of my favorite National Parks that have rivers and history.

Antietam National Battlefield

Antietam National Battlefield | National Park Service

Walk the Miller’s Cornfield at dawn, following in the footsteps of Hooker’s I Corps as it opened the bloodiest day in American history. End your trip in the evening, crossing the Burnside Bridge over Antietam Creek, named for the Union IX Corps Commander who frittered away the lives of his soldiers by trying to force the crossing of the narrow stone span (which still stands today) in the face of determined Confederate fire.

In between, you will join with the thousands who annually become Antietam Partners because they discover that they “value the sacrifice and serenity that is Antietam.”

Shiloh National Military Park

Shiloh National Military Park | National Park Service

In southwest Tennessee you will find one of the best preserved and most haunting of all the Civil War battlefields owned by the National Park Service. If you go, make sure to walk Fraley’s Field at first light.

Imagine how the soldiers of the 25th Missouri Regiment must have felt when they found that the woods in front of them were not empty, but in fact filled with Confederate General A.S. Johnston’s Army of Mississippi. And also make sure you arrive at the northern end of the park, at the bluffs overlooking the Tennessee River, as night falls.

If you’re quiet, you can hear the distant echoes of the wounded and panicked men of General Grant’s Army of Tennessee lying along the shore, while General Buell’s Army of the Ohio disembarks from their boats by torchlight at Pittsburgh Landing, arriving just in time to save Grant’s army, and the nation.

Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania Military Park

Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania Military Park | National Park Service

More than 100,000 Americans were casualties at the First and Second Battles of Fredericksburg, the Battle of Chancellorsville, the Battle of Salem Church, the Battle of the Wilderness, and the Battle of Spotsylvania all of which are commemorated and preserved by this national park.

During the Battle of Fredericksburg in December, 1862, U.S. troops crossed the Rappahannock River under fire, and the view of their subsequent doomed assault on Marye’s Heights led General Lee to utter his famous quote: “It is well that war is so terrible, or we should grow too fond of it.”

Cross the river yourself and climb the heights in their footsteps, or hike your way through the tangled underbrush of the Wilderness, and feel the weight of history on your shoulders.

Lowell National Historical Park

Lowell Trolley | Liz West

History isn’t all bullets and battles. It’s the story of ordinary men and women most of whom led ordinary lives and did ordinary things. But when you look back through the lens of time, the ordinary often appears to us as extraordinary.

Many of my relatives sailed across the ocean from Ireland to find religious and economic freedom in America. They found it in the water-powered mills and factories of Massachusetts, and while we would probably be horrified at the conditions found in an Industrial Revolution-era factory, they were grateful to escape famine and oppression and to have the opportunity to build their futures in the Land of the Free.

Lowell NHP is the monument to the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution in America, and to the men, women, and children who lived and died in it. It’s a park commemorating not just the Industrial Revolution, but the people behind it.

Minute Man National Park

Minute Man National Park | National Park Service

It’s where, one could argue, America began, with the Shot Heard Round the World fired over the Wild and Scenic Concord River at Old North Bridge.

You can get chills down your spine standing by “the votive stone” near the “dark stream” and reciting Emerson’s Concord Hymn.

These are just a few of the great National Parks where history and rivers intersect. But what’s great about these parks is that they are not just static fields or buildings. They are places of learning and reflection.

Most of the major National Parks have Junior Ranger programs where kids are encouraged to answer questions, to think about what they are seeing and experiencing, and to learn lessons that go far beyond what they get in the classrooms. My daughter has been “sworn in” as a Junior Ranger at three parks so far, Gettysburg National Military Park, Antietam National Battlefield, and Independence Park in Philadelphia. She declared to me just last week that she wants to earn her badge at all the Parks, so we’ve got some work ahead of us!

These Parks are her legacy and the legacy of all who come after us, as they are the legacy of those who came before us. Not just all Americans, but all people – past, present and yet to come – who yearn for and believe in freedom are the inheritors and guardians of Old North Bridge and what it represents. The battlefields around Fredericksburg, at Shiloh, and at Antietam were painful steps toward fulfilling the promise of freedom and equality to all. And the triumphs and tragedies of the working class people who brought their talents from distant shores and struggled under tremendous odds to build a better life are captured in the mills and waterways in Lowell.

If you love rivers and you want to feel history come alive, #FindYourPark! And bring a friend.

Now it’s your turn

What’s your favorite national park? Have you been able to celebrate at it this year?

One of the newer national parks, the Congaree was protected because of the local support. The Congaree was first protected as a National Monument in the mid-1970s. The area escaped the bite of chainsaws thanks to the strong advocacy of local citizens who didn’t want to have clear cut one of the last remnants of virgin, bottomland forests in the Southeast. In 2003, the Congaree became a National Park, a great tribute to the conservation legacy of South Carolina Senator Fritz Hollings.

The Congaree National Park is also great testament to how American Rivers’ Blue Trails initiative can connect people to a river and a park. Coursing some 50 miles from Columbia, South Carolina to the southeastern end of the park, the Congaree River Blue Trail links urban residents to one of the wildest places left in the eastern US. It offers a multi-day paddling adventure as one travels from within view of the state capitol dome into a wilderness that touts some of the tallest trees east of the Mississippi. Countless sandbars just right for a picnic or an overnight camp border the river’s bends while bluffs of multicolored clay contrast the area’s extensive floodplain forests. For those with less ambitious appetites, the park also offers Cedar Creek, a blackwater gem with a tree canopy cathedral that abounds with birdlife well worthy of its designation as a globally important birding area.

The Congaree River Blue Trail collaborative has also brought additional support for the park including citizen backing for adding new lands to the park, involvement in river cleanups and a recreation paddling map for the Congaree River and Cedar Creek that is offered online and as a colorful, printed version available at the park and from local outfitters.

As we mark the 100th anniversary of the national park system, let’s make sure to celebrate Congaree National Park and the Congaree River Blue Trail.

A recent visit to the Congaree National Park website brought home an important landmark in time – 2016 is the 100th anniversary of the National Park Service. And what a great testament to the successes of the National Park system the Congaree is! One of the newer national parks, the Congaree was protected with help from local support. The Congaree was first protected as a National Monument in the mid-1970s. The area escaped the bite of chainsaws thanks to the strong advocacy of local citizens who didn’t want to clear cut one of the last remnants of virgin, bottomland forests in the Southeast. In 2003, the Congaree became a National Park, a great tribute to the conservation legacy of South Carolina Senator Fritz Hollings.

The Congaree National Park is also great testament to how American Rivers’ Blue Trails initiative can connect people to a river and a park. Coursing some 50 miles from Columbia, South Carolina to the southeastern end of the park, the Congaree River Blue Trail links urban residents to one of the wildest places left in the eastern US. It offers a multi-day paddling adventure as one travels from within view of the state capitol dome into a wilderness that touts some of the tallest trees east of the Mississippi. Countless sandbars just right for a picnic or an overnight camp border the river’s bends while bluffs of multicolored clay contrast the area’s extensive floodplain forests. For those with less ambitious appetites, the park also offers Cedar Creek, a blackwater gem with a tree canopy cathedral that abounds with birdlife well worthy of its designation as a globally important birding area.

The Congaree River Blue Trail collaborative has also brought additional support for the park including citizen backing for adding new lands to the park, involvement in river cleanups, and a recreation paddling map for the Congaree River and Cedar Creek that is offered online and as a colorful, printed version available at the park and from local outfitters.

As we mark the 100th anniversary of the National Park Service, let’s make sure to celebrate Congaree National Park and the Congaree River Blue Trail.

Gerrit Jöbsis is a resident of Columbia, SC and directs American Rivers’ efforts to protect and restore the Rivers of Southern Appalachia and the Carolinas.

The Louisiana flooding has been described as “extreme”, “devastating”, “shocking” and the numbers certainly convey the gravity of the situation. 31.39 inches of rain fell in Watson, LA. River crest records were broken by up to 5 feet. 30,000 people were rescued. 60,000 homes damaged and the number keeps rising. Tragically, at least 13 people are dead. Scientists say the chances of a flood like this were at least one in 500.

As astounding as those numbers are, to me the most sobering fact is that this was the eighth 500-year rain event in the United States in just over a year, according to NOAA. Events in Texas, West Virginia, Maryland, and elsewhere have brought the reality of climate change into perspective.

Coast Guardsmen use a flat-bottom boat to assist residents during severe flooding around Baton Rouge, LA | Petty Officer 3rd Class Brandon Giles

On Tuesday President Obama visited Louisiana to take in the scope of the disaster and provide some hope to the people struggling to figure out how to rebuild their lives and homes. It’s clear that significant investments will be needed to make Louisianans whole and make their communities more resilient to the more frequent and extreme storm events we should expect from climate change impacts.

President Obama’s trip comes a day after his administration took an action that should give us all hope for how we recover from future floods. On Monday the Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA) released their proposed rule to update the federal flood standards that determine if and how the federal government invests in development in floodplains. The new standards will ensure that a greater margin of safety is used so that federally funded infrastructure can withstand larger floods. Not only will this reduce damage to infrastructure and keep communities safe, it also helps protect river health by encouraging development to occur on safer, higher ground.

Louisiana Army National Guard vehicles transport flood relief supplies | 1st Sgt. Paul Meeker

The standard will also help rivers and improve public safety by requiring consideration of natural approaches that use floodplains to safely convey and buffer the impacts of floods. Natural flood management approaches like floodplain restoration result in less infrastructure at risk of flood damage and support an array of benefits to rivers and riverine communities including wildlife and fish habitat, clean water, and recharged groundwater supplies.

These changes are the result of lessons learned after past flooding disasters in Louisiana, Colorado, the Northeast, and across the country. They were identified as necessary to the safety of the nation in the President’s Climate Action Plan, the Sandy Task Force Rebuilding Strategy, and Recommendations of the President’s State, Local, and Tribal Task Force for Climate Preparedness.

FEMA is taking comments on their new standard until October 21. There is still work to be done to implement it and other agencies are expected to unveil their own implementation plans in the coming months. In the meantime, we hope the state of Louisiana will utilize the lessons learned from past floods, and the administration will help affected communities rebuild resiliently as quickly as possible.

Guest post by Tyler Shepherd is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Smith River.

I’m not your typical opponent of Tintina Resources’ proposed copper mine in the headwaters of the Smith River.

For over 40 years, I’ve spent my career exploring for, developing, and mining mineral deposits throughout the Americas. I have worked for both small-junior and large-major mining companies in most facets of this business including exploration geologist, permit writer, equipment and plant operator, project manager, and president. Mining is essential to our way of life, just as is agriculture. Everything material in our lives is either grown or mined. Therefore, I do not write this without some trepidation.

Having read through Tintina’s permit application, it is my opinion that this copper mine, if allowed to go forward, will irreparably contaminate the Smith River.

Tyler Shepherd

As an outdoor enthusiast, fly fisherman, and reasonable conservationist, I have had the privilege and pleasure of having floated the Smith River twice. This river truly is a gem and a national treasure. It’s also economically significant to Montana, generating $10 million annually from fishing alone. This figure does not include monies generated by river floaters, wildlife viewers, and other outdoor enthusiasts, as well as downstream water users. This substantial economic benefit can last in perpetuity if we keep the river healthy.

Mineral deposits are not always located where one would prefer to have them. Some mineral deposits, such as those found in parts of Nevada where I spent much of my career, are located in hydrologically closed systems where the environmental risks are manageable. This one, much like the Seven-Up Pete gold deposit on the Blackfoot River, is not. Pollution generated from this mine inevitably will make its way down Sheep Creek, into the Smith River, and eventually into the Missouri River.

Tintina’s copper deposit is sulfide rich with numerous associated metals, some of which are quite toxic. Once sulfide minerals are exposed to air and water, they produce sulfuric acid. This acid accelerates the release of various metals and elements into our environment in a much more toxic state. It may only take a few years, or it may take 50 years, but this pollution will occur.

There is nothing special or unique to the operating plan for this mine that will eliminate the environmental liabilities. Basic chemistry, engineering and physics dictate the proposed exploitation of this deposit.

Mining companies in general tend to come and go based on the economic viability of the deposits, financial situation of the company, and change in management. More likely than not, Tintina will not exist 20 to 30 years from now. Certainly their current management will not be in place, either to safeguard the project or to be held accountable for the pollution that this project will cause. When this mining project shuts down, environmental monitoring and remediation will soon cease due to lack of funding and personnel. This is when pollution and contamination will increase dramatically.

Paddling the Smith River, MT

A possible solution to this dilemma would be to remunerate Tintina for its expenditures to date, and then permanently withdraw the headwaters of the Smith River from any further mining activity. This type of deal has been done before, most notably with the buyout of Noranda’s proposed activities just outside Yellowstone National Park in the 1990s.

Mining has its place, and is important to America. That does not mean mining should be allowed anywhere and everywhere. Some sulfide bearing mineral deposits that are virtually certain to produce acid mine drainage, and are located directly adjacent to or upstream of environmentally sensitive places, should be off limits due to their unacceptably high environmental risks. The Black Butte high sulfide ore deposit, directly upstream of the rare, unique, and environmentally sensitive Smith River should not be allowed to be exploited due to the extreme likelihood of pollution and contamination.

If Montana’s decision-makers, environmental regulators and residents are sincere about wanting to protect the Smith River for future generations, they should keep this copper in the ground.

Tyler Shepherd has spent his career in the mining industry. He now works as a mining consultant and small businessman, currently living in Yakima, Washington.

I have noticed a lot of chatter lately about the situation at Lake Mead. Dramatic overuse, prolonged drought, and the effects of increased temperatures have led to a historically low volume of water stored in the largest reservoir on the Colorado River. One of the most critical components of water in the west is less than 40% full. Yet while some people scramble for a quick fix or point fingers, others see the long game and note the optimism that working together for smart, sustainable solutions can bring. There is hope, there is a roadmap, and together we have the knowledge, skill, and foresight to make it happen.

The Discovery Channel recently produced a new documentary, Killing the Colorado, a made-for-TV version of the lengthy ProPublica series of the same name. The show is excellent, comprehensive, and features a number of voices that you may not expect to be featured in a film about the environment. Imperial valley agricultural producers, water managers, a red-state Senator and a blue-state Governor – all identifying problems facing the basin, and most putting forth an optimistic view that a human-caused predicament can be solved with human-inspired ingenuity.

Structural pillar at Hoover Dam with Lake Mead’s ominous ‘bathtub ring’ in the background | Sinjin Eberle

One quote in particular is poignant – there is a scene with Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper in his office flipping through a binder full of historic water compacts. Upon his observance of the generations of water agreements, he remarks “The thing you realize when you go through these [water] compacts, is that everyone is in this together.” Given the situation facing Lake Mead, a growing chorus of voices around Lake Powell, the birth of the Colorado Water Plan, and a recognition that heathy rivers support healthy agriculture and sustainable economies, we truly are all rowing the same boat together in the Colorado Basin.

But, how can Lake Mead affect Colorado from a thousand miles downstream? Well, due to the Colorado River Compact of 1922, headwaters states like Colorado must send a certain amount of water to the Southwestern states of Arizona, Nevada, and California – it’s the law of the river, and the law of the land. And since when the Compact was developed, California was a fast growing destination, it has priority and can “call” for water if needed. For years, California has had the luxury to get much of the surplus of water that Colorado and Wyoming have sent downstream to be stored in Lake Powell and Lake Mead. But now with prolonged drought, a fast-growing population across the entire Southwest, and a substantial agricultural economy (especially in the Imperial Valley), the era of surplus water is over. As such, Lake Mead is directly connected to Colorado, whether we like it or not, and that connection is the Colorado River.

Lake Powell’s ‘bathtub ring’ hovers more than 50ft about paddler Sinjin Eberle, December 2015 | Forest Woodward

Killing the Colorado does a fantastic job over nearly an hour-and-a-half of highlighting a variety of colorful characters who have recognized that shortage and a lack of water will change everything in the future – that future is now. But while both the show and the written article are excellent at highlighting the situation, they don’t delve deeply into what I think is most important – that real solutions do exist, and we know how to implement them, it simply takes our collective will to get them moving. Solutions like urban and agricultural conservation and efficiency, like reuse and recycling, like innovative water banking and flexible management practices, like continuing the shift towards renewable energy (solar and wind don’t devour cooling water like natural gas and coal plants require). But while these efforts all seem daunting and out of an individual’s control, there are actions that each of us can take every day that together, make a huge difference. Like buying and installing your own rain barrel for your outside plants and flowers, like supporting your local farmer at the farmer’s market – small things that have a great impact, especially when we all do them together.

Solutions do exist, and as Arizona Senator Jeff Flake said “The drought over the past couple of years has awakened all of us to the future we have if we don’t do better planning. There are many things that are out of our control…Planning is so important. Conserving. Recharging. Water banking. Water markets. These are all important things that have to take place.”

Let’s get started!

If you had been biking or driving over Portland’s Hawthorne Bridge around 6pm on August 17, you would have noticed a number of drummers lined up along the railing. You would have heard the beat of the drums, and cheers from the river below. And maybe you would have seen the 200 swimmers – including Mayor-elect Ted Wheeler – jumping into the water, flanked by colorful safety kayakers.

It was the first annual Mayoral River Swim, organized by Willie Levenson and the Human Access Project. The goal: swim across the river together to raise awareness about the need for clean water and celebrate the Willamette River, the lifeblood of our city.

We gathered at the fire station dock on the east side of the river near the Hawthorne Bridge – mostly swimmers, and some with rafts and pool noodles and SUPs. The guest of honor was Ted, an avid swimmer who embraces the river as key to Portland’s identity and quality of life. I overheard somebody affectionately call him “Ted the Trout.” Even better, he brought his young daughter with him. I think she was the youngest swimmer there. I got a minute of Ted’s time as we walked down the ramp to the dock and thanked him for his attention to the river. I told him we’d love to see all the mayors of river cities around the country leading swims across their rivers.

After some brief remarks on the dock, we all jumped in. And if we all weren’t excited and inspired enough, the big bass drums up on the bridge fired everyone up. It wasn’t just a swim, it was an event – something symbolic. People claiming ownership of their river and insisting that it must be clean and accessible for all. The Willamette has come a long way. It used to be so polluted nobody would dream of dipping their toe in. But thanks to major clean-up efforts, the river’s quality is better than it has been in a long time.

We were also here to just have fun. There was a big sense of joy – it’s summer, it’s beautiful and we’re swimming across the river in downtown Portland! I wanted to take it all in – I swam breast stroke for much of the way so I could watch the drummers up above, chat with fellow swimmers and kayakers, enjoy the sunny view of my city from the middle of the river. The water felt great, a perfect cool temperature on a hot August day. We swam diagonally under the Hawthorne Bridge to the beach on the west side. It wasn’t a race – we took our time, stopped to float, just enjoyed ourselves.

The Willamette and other urban rivers face big challenges and the work to ensure clean water and improved access is never really finished. There are always new threats, whether it’s pollution or harmful development or something else. It is hard work, and it takes constant effort on the part of local advocates and conservation organizations. That’s why it is so important to build community and grow the “armies” of people – the “riverlutionaries,” in the words of Willie Levenson – who love the river. And that’s why it’s important to take time to celebrate and have fun (in the words of Edward Abbey, “…you will outlive the bastards.”) Lying on my back in the middle of the river in the bright sun, I felt hopeful despite the challenges.

We’re all swimmers, we’re all in this together, and a river runs through us.