California’s vast water infrastructure is likely the most extensive in the world. It includes the tallest dam in the nation and enormous state and federal water projects that tap rivers flowing from as far away as Wyoming.

Carson Watershed, California | Luke Hunt

On September 27th, 2016, Governor Brown signed legislation that recognizes the state’s watersheds as part of it’s infrastructure. Just as the state’s canals and levees need maintenance and repair, so do our rivers and watersheds. This bill opens the door to using modern infrastructure financing approaches to protect and repair rivers and watersheds. Infrastructure bonds can now be used for restoration and protection. Likewise, it will be easier for utilities to justify investment in watershed restoration. Importantly, watershed degradation should now go on the books as value lost to deferred maintenance. The cost of deferred maintenance and asset condition will be two parts of the State Treasurer’s infrastructure inventory. This inventory should now value California’s watersheds as key water supply assets, on par with pipes and levees.

The short bill is a pleasure to read beginning with: “It is hereby declared…that source watersheds are recognized and defined as integral components of California’s water infrastructure.” Eligible maintenance and repair activities include:

“(1) Upland vegetation management to restore the watershed’s productivity and resiliency.

(2) Wet and dry meadow restoration.

(3) Road removal and repair.

(4) Stream channel restoration.”

American Rivers has long advocated that to ensure our prosperity, we need to invest in our natural water infrastructure, just as we maintain our built systems. Now California has made it official!

[metaslider id=33742]

Guest post by Willie Dodson is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Russell Fork River.

For many years, passersby on route 80 near the old high school in Haysi, Virginia, could spot a strange figure out in the Russell Fork River. Any day when the weather was warm enough and the water was low enough, there she’d be, wearing a big floppy hat, and scratching around with a garden hoe at the cobble and mud along the river’s bed. At first glance, this individual (and an individual she was indeed) might have seemed to be a little off, as they say. There was, however, a meaning and a method to her work. Gary Buffington, a cross-country cyclist traveling through Haysi in 2007, chronicled his encounter with just such a character in his blog and paraphrased here:

I rang my little bike bell and yelled, “What are you doing?”

She said, “I’m moving the river!”

I shouted down, “Why?”

She said, “My house flooded in 1976 and I’ve been working on it ever since.”

So I said, “It sounds to me like the project is working perfectly if it hasn’t flooded since you began the work.”

She said, “I know. I think I’m a civil engineer and should be working for the Army Corps of Engineers.”

As I was about to pull out I shouted, “What’s your name?”

She said, “Vivian Owens, and I’m 78 years old.”

As I sped off I shouted down to her: “Goodbye Vivian Owens of the Army Corps of Engineers.”

And she said, “Have a safe trip and God be with you.”

Vivian Owens loved the Russell Fork River, the mountains that held it in place, and the communities along it. From this love grew an impulse to serve her land and people. Through the Friends of the Russell Fork, a group for which she served on the Board of Directors, Vivian volunteered countless hours cleaning up the river, monitoring its ecological well-being, and sharing its peace and beauty with others.

Vivian Owens recently passed away on August 23, 2016. Two days later, bereaved, and in the midst of funeral planning, her daughter Tammy was gracious enough to meet with staff of Appalachian Voices and the Southern Appalachian Mountain Stewards to discuss the Russell Fork, the impacts of past and potential new strip mining, and the work of building a new economy in Southwest Virginia. Some of her thoughts are captured below:

It was probably about 5 o’clock this morning; I literally felt a poke, and I heard mom’s voice say, “Tam, that’s enough. Get going. Get on with it.” So that’s why meeting you guys here was important to me — because this was important to her.

I remember growing up, when the first strip mine came in. I can still remember how devastated I was with what that did to the creek and the river and the spring-fed pond by my house in Campbell County, Tennessee, where we lived at the time. Mom encouraged me to debate and to speak out. She did too. She spoke out about what the strip mining was doing to the land and to the water sources, the well water, all those things.

Growing up, I was always in the woods. I spent my entire childhood barefoot, playing in those mountainsides, exploring old Indian ruins and catching crawdads. In the summertime, I’d get up and get my chores done, and I would be in the mountains all day long swimming in the river and running up and down the railroad tracks. Then the strip mining started. I remember just how devastating that was. There was no protection back then. It ruined our well water and everybody else’s.

I think people fundamentally know that the coal and the gas is gone, but it’s like a death. We’ve lost what was the only way of life in this area from the point that these little towns popped up. It was all we knew. It was all we did – was coal. So I feel just like in any type of grieving process there’s denial, there’s anger; and I feel like right now we’re still in that stage of denial coming into the anger.

People like my mom – that whole age group – are dying. So they’re leaving us to make a new way for this area. We have that responsibility. It needs to be in the frame of mind like my mom taught – caring for the river, caring for the mountains. No more raping the mountainsides! No more hunger games! You got the coal, so leave us be. Like this Doe Branch Mine – yeah there’s a few million dollars and maybe a new road coming in here, but in the larger view of our future, what does that really mean? It’s just prolonging the agony.

So what are we gonna create now? Are we gonna live with the ghost of that, or are we gonna bring back the life and the beauty and the culture?

As far as trying to help the community establish a new viable economy that doesn’t include further devastation of these mountains and the river, it just feels natural to me. This is what I’m supposed to be doing because it’s what mom raised me up to do.

Carrying forward her mother’s legacy, Tammy Owens is working with Appalachian Voices and anyone else who will extend the effort, to build a new economy in Haysi and Southwest Virginia that values the land and the people, not just the minerals and labor. An herbalist and organic farmer, Tammy is embarking on an innovative ginseng cultivation project utilizing both healthy wooded slopes and old mined lands. She also hopes to someday establish a tubing and kayaking business at the family homeplace that her mother worked so hard to protect from rising waters.

As we work together to build a fair, resilient and diverse economy amidst the scars of the old, it is increasingly clear that further liquidation of our natural assets in the form of mountaintop removal strip mining is a step in the wrong direction economically, on top of being an ecological catastrophe. Though the industry has died back significantly, mountaintop removal is still happening… but it doesn’t have to be. Please help us stop the proposed Doe Branch mine and take one step towards a new economy in Appalachia that works for everybody.

Willie Dodson is the Central Appalachian Campaign Coordinator for Appalachian Voices. Appalachian Voices is an environmental non-profit committed to protecting the land, air and water of the central and southern Appalachian region, focusing on reducing coal’s impact on the region and advancing their vision for a cleaner energy future.

Willie Dodson is the Central Appalachian Campaign Coordinator for Appalachian Voices. Appalachian Voices is an environmental non-profit committed to protecting the land, air and water of the central and southern Appalachian region, focusing on reducing coal’s impact on the region and advancing their vision for a cleaner energy future.

There’s an old saying, “You can’t catch fish in a dry pond.” That wisdom applies to a lot more than fishing, and it also applies to more than dry ponds. Specifically, it applies to fishing in healthy rivers. So as we celebrate National Hunting and Fishing Day, it seems to make sense to invite our nation’s rivers to the party.

Though I hunted some a long time ago, this holiday for me is all about fishing. And like two tributaries that come together to make a bigger river, my love of rivers is completely mixed together with my love of fishing.

Greybull River, Montana | Steve White

Discovering new rivers: When I get a chance to explore and fish a new river, the feeling is like that of throwing a birthday party. Every new run or pool is like opening a different wrapped gift – each one unique, but all part of one wonderful celebration.

Revisiting familiar rivers: Having gotten to know some rivers well enough to be considered “home waters” at various points in my life, when I have a chance to revisit them, it’s like a homecoming celebration. It’s a familiar place, and with any luck, I might get a chance to visit with some old friends (both those fishing with me and those at the other end of the line).

The similarity between these different types of parties is that they both depend on having a healthy river to fish in. You’d never serve a birthday cake on a cesspool, and you’d never throw a homecoming party at the city dump. You’d never go fishing in an algae bloom, and you wouldn’t cast your line into a polluted stream.

That’s why it’s so important to protect wild rivers, restore damaged ones, and fight for all of them. Imagine the look on a 5-year-old’s face when he opens a new present or when she catches her first fish. It’s the same look, the same experience, the same joy.

On this National Hunting and Fishing Day, please join us in making sure that we can keep the celebration going throughout the year and for years to come by joining American Rivers and by visiting our Anglers Fund website.

Enjoy the holiday and all your time on the river.

To celebrate the 25th anniversary of National River Cleanup®, American Rivers teamed up with Charleston Waterkeeper, Keep Dorchester County Beautiful, Dorchester County, Nature Adventure Outfitters, and local residents in Summerville, SC to clean the Ashley River Blue Trail. To talk more about the work we did and the importance of the Ashley, Andrew Wunderley, Charleston’s Waterkeeper, has agreed to share a blog.

Kayaker sets out to find trash on the Ashley River. | Gerrit Jobsis

Charleston, South Carolina sits at the heart of a historic and ecologically valuable estuarine ecosystem. It supports countless species of plants, birds, fish, and mammals and more than 712,000 residents. The area’s beaches, salt marsh, tidal creeks, rivers, and harbor provide our community with a unique and very special quality of life that is connected to and inseparable from the surrounding water.

In an area renowned for its natural beauty the Ashley River is special. It rises from the forested Wassamassaw and Great Cypress Swamps as a tannin colored blackwater river. Near Summerville, the river’s channel deepens and begins to feel the ebb and flood of the ocean’s tides.

The river slowly bends and winds past historic Fort Dorchester with its colonial oyster-tabby forts and St. George’s Bell Tower. Downstream, its banks widen into large expanses of protected salt marsh near Dayton Hall, Middleton, and Magnolia plantations preserving a viewshed unchanged for hundreds of years.

Further along, the Ashley River’s channel widens feeling the full and tidal cycle and its bucolic beauty gives way to abandoned phosphate plants and industrial sites from the early 1900s. Just past the historic and densely populated Charleston peninsula, the Ashley River joins the Cooper River to form the Atlantic Ocean.

The historic and natural beauty of the Ashley River and our coastal estuary haven’t gone unnoticed. The Charleston metro region is one of the fastest growing in the United States. Some reports estimate that nearly 50 people move to our region every day. This intense and aggressive growth threatens the very essence of our community—it’s rivers.

Chris William’s catch of the day, a rusted out propane tank. | Gerrit Jobsis

Today, the Ashley River is a hotspot for all manner of debris from plastic material like bottles, styrofoam, and bags to construction debris like lumber and sheet goods. The historic floods of October 2015 only made the pollution worse. The Ashley River can’t clean itself, and it’s our responsibility to look after the river and ensure it stays healthy. Fortunately, the Ashley River has an engaged community of stewardship groups and local citizens who love it, understand its historic and ecological importance, and are actively working to take care of it.

Charleston Waterkeeper is proud to stand with American Rivers, Keep Dorchester County Beautiful, Dorchester County, Nature Adventure Outfitters, and river stewards both familiar and new to cleanup one of the most ecologically important sections of the Ashley River. We got our feet wet and our hands dirty on Saturday, September 17th as part of the 25th anniversary of National River Cleanup®. At the end of the day, we were tried and dirty, but with the help of 250 dedicated volunteers, 2,360 pounds of trash were collected and either recycled or properly disposed.

Cleanup events like this are important to preserving and protecting the Ashley River for future generations. They remove debris that might otherwise harm the river’s aquatic and plant life – making the river healthier and preserving its beauty for all. They also help inspire people to take action and instill a sense of responsibility for the river’s health and future. We now have a cleaner river for everyone to enjoy, and some new Ashley River stewards to help keep watch over the river where Charleston was founded.

[metaslider id=33600]

Guest post by Erin Savage is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Russell Fork River.

The history of the Doe Branch Mine in Southwest Virginia is long and complicated, and its future remains unclear.

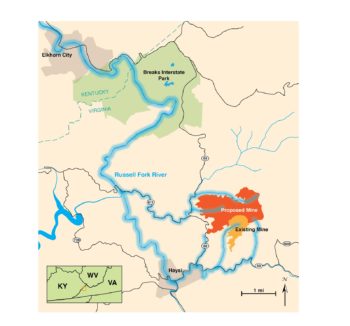

The mine is owned by Paramont Coal Company, once a subsidiary of Alpha Natural Resources. Until recently, Alpha was one of the largest mining companies in the country, but is now emerging from bankruptcy. The Doe Branch Mine started with plans for a 245-acre surface coal mine in 2005, but it now has the potential to grow to 1,100 acres. If the current plan moves forward, the mine would include five valley fills and 14 wastewater discharges that would drain into tributaries of the Russell Fork River — a renowned resource in the region for river recreation and the star attraction of the Breaks Interstate Park.

While there is a long history of coal mining in the Russell Fork watershed, water quality in the river has improved over the last several decades due to better regulations and the watchful eye of local residents. At a time when coal mining is declining in Appalachia, the Doe Branch mine is among the largest mines still being pursued in Southwest Virginia, and it would undoubtedly lead to significant water quality impacts.

The mine is also part of a large, controversial highway construction project known as the Coalfields Expressway. Some believe the Expressway will bring much needed economic development opportunities to the region, but others believe it unnecessarily enables additional surface mining and does not adequately consider what is best for nearby communities. Though a portion of the Doe Branch mine has been approved by state and federal agencies, the expansion does not have final approval. Little work has been started on any portion of the mine over the last decade, beyond some tree clearing.

In 2012, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued an objection to the company’s application to increase the size of the mine. Specifically, the EPA objected to the application for additional wastewater permits under the Clean Water Act. The wastewater would be discharged into several tributaries of the Russell Fork that are already impaired by mining-related pollutants, according to Virginia’s list of impaired waterways. In order to secure discharge permits, the company must show that it will not increase the overall impairment of the watershed.

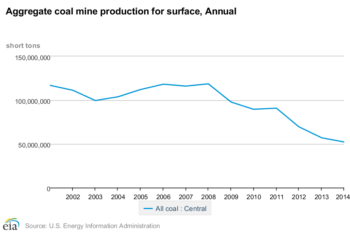

Trends for coal mining production in Central Appalachia. This decline has continued into 2015 and 2016.

Since hitting its peak in 2008, coal production in Central Appalachia has declined precipitously. Alpha’s dominance in the Central Appalachian coal market has not shielded it from the economic downturn. The company declared bankruptcy in August 2015, creating a lull in the Doe Branch permit application process.

On July 26, 2016, Alpha announced its emergence from Chapter 11 bankruptcy. The plan to emerge from bankruptcy involves the formation of two new companies. One is a privately held, smaller Alpha, which will retain most of the Central Appalachian mines. The other is Contura Energy, formed by Alpha’s senior lenders, which purchased Alpha’s Wyoming, Pennsylvania and better-performing Central Appalachian mines. Doe Branch is included in the short list of Central Appalachian mines that Contura will own.

Before emerging from bankruptcy, Alpha stated that the Doe Branch mine is not part of its 10 year plan. Now that Contura owns Doe Branch, the mine may be more likely to move forward. Just last month, a new Clean Water Act permit draft was issued by the Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy. This new draft may be an attempt to address the objections raised by the EPA. Given the importance of the Russell Fork, the damage already done to its tributaries by mining, and the need for a serious economic shift in the region, the EPA should uphold its objection to this mine. Urge them to do so now.

Erin Savage is the Central Appalachian Campaign Coordinator for Appalachian Voices. Appalachian Voices is an environmental non-profit committed to protecting the land, air and water of the central and southern Appalachian region, focusing on reducing coal’s impact on the region and advancing their vision for a cleaner energy future.

Erin Savage is the Central Appalachian Campaign Coordinator for Appalachian Voices. Appalachian Voices is an environmental non-profit committed to protecting the land, air and water of the central and southern Appalachian region, focusing on reducing coal’s impact on the region and advancing their vision for a cleaner energy future.

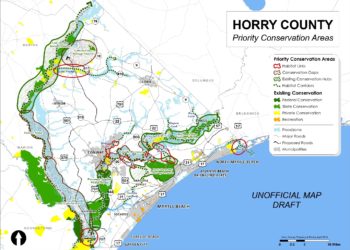

Today’s post is by guest blogger Leigh Kane, a Community Development Planner for Horry County Planning & Zoning in Horry County, South Carolina.

Horry County is located along the northern coast of South Carolina and is well-known for being home to Myrtle Beach. Beyond the urban areas of the coast, the county consists largely of wetlands, forests, and farmland.

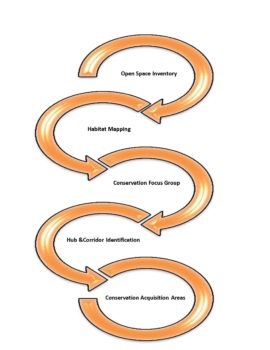

Like many parts of the country, Horry County has seen extensive development over the last few decades, growing from 69,992 residents in 1970 to an estimated 309,199 in 2015. Such extensive growth has the potential to degrade water quality and fragment habitat. In addition, it can threaten public access waterways and other forms of outdoor recreation. Because the county’s diverse water resources interconnect its urban and rural areas, it is an ideal location in which to apply green infrastructure principles through parks and open space planning.

In January of 2015, Horry County Planning & Zoning, in cooperation with Horry County Parks & Recreation, initiated an update to the county’s Parks and Open Space Plan. The ultimate goal was to identify the county’s recreational needs and areas to target future conservation. This planning effort involved a community survey and focus groups focused on identifying recreational needs, in addition to a conservation based focus group to identify gaps in conservation. Citizen input revealed a desire for multi-purpose parks that serve all ages and activity levels, incorporating both passive and active facilities. Recreational trails and other outlets for outdoor recreation were also strongly desired.

Beyond resident input, conservation organizations, including private, local, state, and federal agencies, met to discuss conservation acquisition priorities in the county. The group discussed habitats that were significant to their missions, the location of existing conservation hubs, and the critical linkages between them. The group also discussed areas where development pressure is more eminent and where development has already been approved in relationship to these habitat corridors. Having a diverse group of conservation and land managers at the table helped ensure that the best available experts informed the development of the priority conservation map to include in the plan. This conceptual map is just one of the draft products that have resulted from the planning process. The Waccamaw River serves as one of the priority areas on the map, as it links existing conservation hubs and protects lands located within the floodplain. Other areas were identified as well do to the habitats within them and the linkages they provide between habitats.

Because each conservation organization has their own mission and varying resources, and realistically it takes a willing property owner to sell their land or establish an easement, no ranking was assigned to the priority conservation areas. Horry County Government does not frequently acquire land for open space acquisition because open space acquisition comes with the responsibility to manage for wildlife or habitat enhancement. Being such, the county relies upon the collaborative efforts of our conservation partners to protect significant habitats.

The plan, while still in draft form, recommends that the county continue to collaborate with area conservation partners to provide recreational access to area waterways and other natural lands. The county will also continue to revisit its land development regulations to ensure that quality open space is preserved in new residential subdivisions. Beyond this, the county will also continue to expand opportunities for outdoor recreation experiences at existing and future recreation facilities. The Horry County Parks and Open Space Plan is still undergoing development; therefore, the Priority Conservation Areas map remains unofficial at this time.

The plan, while still in draft form, recommends that the county continue to collaborate with area conservation partners to provide recreational access to area waterways and other natural lands. The county will also continue to revisit its land development regulations to ensure that quality open space is preserved in new residential subdivisions. Beyond this, the county will also continue to expand opportunities for outdoor recreation experiences at existing and future recreation facilities. The Horry County Parks and Open Space Plan is still undergoing development; therefore, the Priority Conservation Areas map remains unofficial at this time.

Photo Credit: Waccamaw River, Gator Bait Adventures – Chris Ochsenbein

American Rivers’ Room for Rivers program improves community safety and ecosystem health in the California Central Valley region by reconnecting rivers to their floodplains. This program is currently focused on advancing model floodplain-restoration projects to restore critical habitat for fish and wildlife and transform flood management to create a more resilient and sustainable river management paradigm.

Through recent grants from the California Proposition 1 grant program and Wildlife Conservation Society, American Rivers has recently had a huge boost in support of our Central Valley Floodplain Restoration efforts. In the last year, we have secured over $7 million in funding for 5 different on-the-ground multi-benefit floodplain restoration projects along the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers in the heart of the Central Valley. Private support from foundations, such as the Argosy Foundation, California Water Foundation, and Leavens Family Foundation, has also provided critical seed money to develop and advance these efforts as well as policy level flood management reform through our work advocating for multi-benefit management measures in the 2017 update to the Central Valley Flood Protection Plan.

Some of our exciting on-the-ground work includes:

Great Valley Grasslands Floodplain Restoration

This project aims to reconnect approximately 220 acres of grassland/floodplain wetland along the lower San Joaquin River in the Great Valley Grasslands State Park, which lies adjacent to the San Luis National Wildlife Refuge Complex near Los Banos, CA. The project is planned to be completed in 2019.

View looking Northwest along the levee that currently separates the river from historic grasslands/floodplain. This levee will be breached in various locations to reconnect the river to its floodplain and provide more frequent inundation to benefit endangered species such as Chinook Salmon. | Daniel Nylen

View looking southeast showing natural erosion into levee. This is one likely area of levee breaching to take advantage of natural processes that are already trying to reconnect the river to its floodplain. | Daniel Nylen

Paradise Cut Floodway Expansion and Floodplain Restoration

In collaboration with local and state agency partners, this project will expand an existing flood bypass near the town of Lathrop, CA to increase flood conveyance capacity while simultaneously providing more frequently inundated floodplain habitat. In addition, American Rivers will be working to secure conservation easements on lands in the expanded bypass to benefit endangered species such as Swainson’s Hawk.

View of existing weir with the San Joaquin River in the background that controls flood flow entry into existing bypass. A new weir will be built upstream of this one to provide an additional entry point for flood flows into the expanded bypass. | Daniel Nylen

View of likely location of new upstream weir to help flood flows from the San Joaquin River flow into the expanded bypass, thereby relieving stress on downstream structures and communities while also providing improved floodplain function and more habitat area. | Daniel Nylen

Yolo Bypass Floodway Expansion and Floodplain Restoration

This exciting project is a multi-faceted bypass expansion and habitat restoration project in the Yolo Bypass near Sacramento, CA. In partnership with the California Department of Water Resources, CalTrout, and Knaggs Ranch, we are working on near-term habitat restoration elements within the bypass expansion footprint. We will be improving connectivity for adult Salmon and Steelhead fish passage in the bypass, and developing novel ways to manage agricultural lands for fish – specifically using rice fields to “farm” juvenile salmon in winter months when fields are fallow and can be flooded to provide critical rearing habitat.

View of flooded rice fields at Knaggs Ranch, which is experimenting with managing rice fields for salmon habitat in winter months. | Carson Jeffres

These model projects highlight the importance of a multi-benefit approach to flood management in the Central Valley and beyond if we are to provide a sustainable water supply, flood protection, a working agricultural economy, and ecosystem recovery. Giving rivers more room to move by expanding floodplain area both decreases flood risk by lowering the water level of the river during floods, but also provides critical floodplain habitat and function – one of the most critical habitat types for many of our endangered and threatened species in the Central Valley. For example, a recent report aimed at valuing Central Valley floodplains concluded that the three biggest “value lines” for connected floodplains were 1) reduced flood stage (water level); 2) habitat; and 3) agriculture, each of which can generate benefits valued in the thousands of dollars per acre per year.

Small, regular floods that inundate riverside floodplains are essential to a river’s health, and provide a wide variety of benefits to wildlife, fish and people. When we manage rivers wisely, we can keep communities safe and enjoy all of the benefits healthy rivers provide. Healthy floodplains are nature’s flood protection.

American Rivers continues to advance on-the-ground model projects throughout the Central Valley and work on policy reform at the state level to showcase the success of a multi-benefit flood management approach.

Much anticipated and much needed restoration in Hope Valley Meadow has just begun. This 1600-acre meadow complex is one of the largest and most beloved in the Sierra. Hope Valley is located just south of Lake Tahoe and is a popular recreation destination, as well as an integral ecological component of the West Fork Carson River, home to an important recreational fishery and the drinking water supply for many communities in Western Nevada.

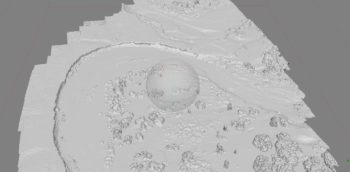

Aerial map mosaic of upper reach of restoration project showing pre-restoration baseline conditions. | Daniel Nylen

American Rivers, Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest, California Department of Fish and Wildlife, Alpine Watershed Group, Friends of Hope Valley, Institute for Bird Populations, Trout Unlimited, and Waterways Consulting have been planning this restoration for 5 years. The Sierra Nevada Conservancy, National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, California Wildlife Conservation Board, Wildlife Conservation Society, and California Department of Water Resources funded the project, with additional support from local communities and Sorenson’s Resort.

The project team completed Phase 1 last fall, which stabilized 130 feet of streambank using a log crib structure. This year’s work includes a much longer section of river upstream of Highway 88, and will improve habitat along 6,000 feet of river by re-creating floodplains and revegetating banks and sand bars.

Oblique view looking North at a section of river that will receive streambank stabilization treatments. | Daniel Nylen

American Rivers recently completed on-the-ground and aerial photo reconnaissance to document pre-restoration conditions in order to have a baseline to compare post-restoration conditions to, and to be able to quantify this change. This included sending up our new Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV), or “drone”, to map current channel conditions and feature locations.

These aerial images can also be used to generate 3D models of the terrain using complex but elegant photogrammetry techniques and software, which can be used to monitor changes in more detail.

The reconnaissance also included ground-based photopoints to document changes up close and on the ground.

[metaslider id=33483]

Please continue to follow our progress on this important project as we post updates during and after construction.

American Rivers congratulates our partners at the City of Rockingham for their recognition as the Municipal Conservationist of the Year at the North Carolina Wildlife Federation’s 53rd Annual Governor’s Conservation Achievement Awards. These prestigious awards, first given in 1958, are a long-standing effort to honor individuals, governmental bodies, organizations and others who have exhibited an unwavering commitment to conservation in North Carolina. By recognizing, publicizing and honoring these conservation leaders—young and old, professional and volunteer—the North Carolina Wildlife Federation hopes to inspire all North Carolinians to take a more active role in protecting the natural resources of our state.

Rockingham is a city with a vision and a serious commitment to natural resources. Highlights over the last few years include the first Urban Wildlife Conservation Area in North Carolina, featuring walking trails, boating, fishing and wildlife viewing. Rockingham completed the removal of Steele’s Mill dam with American Rivers which paved the way for the establishment of the Hitchcock Creek Blue Trail, 14 miles of designated paddling near the Pee Dee River. Want to know more about the Hitchcock Blue Trail? Check out this video:

On Wednesday, in it’s largest expansion since 1949, Yosemite National Park grew to include 400 acres of lush meadow. Ackerson Meadow, along the park’s western boundary, was part of John Muir’s original plan for Yosemite. It’s conservation and addition to Yosemite has been a top conservation priority for decades.

American Rivers’ chapter in Ackerson Meadow started in 2012 when we forged a strong friendship with the landowners, Robin and Nancy Wainwright. Along with the Wainwrights, we set a vision to add the meadow to Yosemite National Park. In 2013, with a grant from the Sierra Nevada Conservancy, the property was appraised. After the appraisal, we brought together the Wainwrights, the National Park Service, and the Trust For Public Land to work together to bring our vision to fruition. On September 7th, with funding from the Yosemite Conservancy and an anonymous donor, the Trust for Public Land purchased the property and donated it to the Park Service.

Protecting and restoring headwater meadows is part of American Rivers’ California focus and the Sierra Nevada Conservancy’s Watershed Improvement Program. Together we have partnered on a number of projects to improve the health of the Sierra Nevada, California’s primary source of clean water. Through this addition to Yosemite National Park, Ackerson Creek – which flows through the property before flowing into the Wild and Scenic South Fork of the Tuolumne River and the greater San Joaquin River – will have it’s water quality protected from threats for years to come.

[metaslider id=33422]

Guest post by Harpeth River Watershed Association is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Harpeth River.

We are happy to report good news for one of America’s Most Endangered Rivers® of 2015, the Harpeth River in Tennessee. In August 2016, Judge Sharp of the U.S. District Court in Nashville approved the settlement of the federal Clean Water Act citizen suit brought by Harpeth River Watershed Association (HRWA) against the City of Franklin, TN in August 2014. The court enforceable settlement is designed to bring Franklin into compliance with the terms of the state permit for the city’s sewage treatment plant. Franklin’s sewer plant is the largest single source of permitted discharge of pollutants into the State Scenic Harpeth River.

Heron on the Harpeth

The Harpeth was highlighted on American Rivers’ annual list of endangered rivers in 2015 in part due to concerns over unpermitted discharges of wastewater into the river. The river’s water quality is impaired from unacceptably high levels of pollutants that feed harmful algae growth that can cause dangerous conditions for wildlife and public health according to the TN Department of Environment and Conservation. This court-enforceable settlement, if faithfully implemented by Franklin, will improve the water quality of this very popular Tennessee State Scenic river resource flowing through Nashville and one of the fastest growing regions of our state and country.

The significance of this effort for clean water and public participation in government include:

- Franklin brought into compliance with state sewer plant discharge permit

- Harpeth River will see reduced pollution if all aspects of settlement are implemented

- Prevention of dangerous algae and toxic conditions in Harpeth River

- Publicly accessible water quality monitoring of river conditions is expanded

- Increased support for new pollution reduction plan being developed for the entire Harpeth River

- Federal Court validation that citizens have the right to participate in and comment on government decision-making without retaliation

- No sewer rate increases related to the lawsuit

Next Steps Toward Recovery of Harpeth Already in Motion

Tubing on the Harpeth River

This settlement begins the next stage of a broad community effort to restore the State Scenic Harpeth River. Franklin and HRWA have already agreed on locations for water quality monitoring in the river as required, and Franklin is in the process of installing monitoring equipment based on the state’s approval. Such information is essential to the new pollution reduction planning process for the entire Harpeth River that has been put in motion with the settlement. The TN Department of Environment and Conservation (TDEC) announced the start of this effort, called a “Total Maximum Daily Load” (TMDL) last year, with HRWA, Franklin, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and the U.S. Geological Survey as the core partners. The process of formulating the TMDL plan will require several years to determine how much pollutant the Harpeth River can receive and still meet water quality standards, and to allocate that pollutant load among the various sources.

This successful settlement is one of many significant milestones over our 15 years that have already resulted in improving water quality in one of America’s Most Endangered Rivers. Our efforts have led to the launching of the first comprehensive pollution reduction plan for an entire river system in the Southeast. We are also now working with Franklin and TDEC on establishing conditions for the new permit for the expansion of Franklin’s sewage treatment plant, which needs to reduce pollution loads in the river.

American Rivers and the Harpeth River Watershed Association thank YOU for taking action on behalf of this special place!!

The Harpeth River Watershed Association in middle Tennessee is dedicated to preserving and restoring the ecological health of the Harpeth River and its watershed. Our work leverages the scientific and technical training and experience of our staff and advisors with the efforts of a diverse corps of volunteers who are crucial to every aspect of our programs.

The Harpeth River Watershed Association in middle Tennessee is dedicated to preserving and restoring the ecological health of the Harpeth River and its watershed. Our work leverages the scientific and technical training and experience of our staff and advisors with the efforts of a diverse corps of volunteers who are crucial to every aspect of our programs.

Photographer and filmmaker John Gussman has been documenting the restoration of the Elwha since the first chunks of concrete dam fell five years ago.

“It’s a shining light,” he says. “The success on the Elwha shows we can actually fix things.”

Now that the dams are gone, Gussman, a resident of Sequim, WA has witnessed what he describes as the “rapid recovery of nature” — the sediment that has moved downriver to restore the beach at the river’s mouth, to the plants and trees reclaiming land once drowned by reservoirs, to the salmon and other fish and wildlife rebounding.

“Nature knows best,” he says. Gussman co-directed the film Return of the River that tells the Elwha’s story.

I was on the Elwha in September 2011 when the world’s biggest restoration project kicked off. Elwha Dam and Glines Canyon Dam had blocked the river for roughly 100 years, completely blocking salmon from historic habitat and destroying the river central to the culture and heritage of the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe.

I remember standing on Elwha Dam, watching salmon circling in the pool below. I remember being amazed that even after all this time, they were still returning, still trying to get upstream.

Now they can.

Elwha Dam was gone for good in March 2012. Glines Canyon Dam, the tallest ever removed at 210 feet high, was gone by September 2014. The journey began in 1978 when Elwha Dam failed to pass its safety inspection. The tribe worked with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) to conduct a failure analysis on the dam and demonstrate the catastrophic flood risk to the reservation. This catalyst sparked a decades-long effort to restore the Elwha River with unrelenting work by the tribe and conservation groups, including American Rivers.

I asked Robert Elofson, River Restoration Program Director for the tribe, how he feels now that we’ve hit the five-year mark. He says the tribe “takes pride that it has played a lead role in such a successful project” and tribal members are looking forward to resuming fishing for ceremonial purposes next year (a fishing moratorium has been in effect since 2011 to let fish populations rebound).

He has seen the benefits of dam removal first hand, from the crabs he has caught at the river’s mouth to the elk sign he noticed on the former Lake Aldwell reservoir lands.

It’s rare that we have a chance to make a river truly wild again, and on the Elwha we did. Eighty-three percent of the river is protected inside Olympic National Park. The dams were the only major impact to the river – so since the dams have come down, the river has been a one-of-a-kind laboratory to watch a river come back to life.

This special report from the Seattle Times sums up the ongoing transformation:

Elk stroll where there used to be reservoirs. Bigger, fatter birds are bearing more young, and moving in to stay. A young forest grows where there was blowing sand in the former reservoir lakebeds. Seeds tumble down the river’s coursing current. The big pulse of sediment trapped behind the dams is passed; the river has regained its luminous teal green color, and its channel is stabilizing.

Logs are tumbling and stacking in the river, building complex, braided channels, islands and jams.

And fish are booming back: More than 4,000 chinook spawners were counted above the former Elwha Dam the first season after it came down. Overall, fish populations are the highest in 30 years. And that’s before the first progeny of salmon and steelhead going to sea since dam removal come back this year.

“It has been a real success,” Elofson says.