It goes without saying that the Grand Canyon is a special place.

I had the great fortune of spending 10 days with a variety of folks rafting down the Colorado River through this great American treasure recently. The trip was with oar boats, for my money the only way to travel the canyon. We did have a motor driven “Mothership”, a 37 foot raft that carried much of the food and other gear supporting the trip. The boats had already been on the river for seven days, coming down from Lee’s Ferry, and some of those travelers were continuing with us.

We rafted through many rapids, some the biggest in North America, but we also drifted through many more miles of calm water, slowly wandering among the magnificent rock temples built through many eons of Earth history. It was sublime.

The first day we woke well before dawn at the Bright Angel Lodge on the Canyon’s South Rim so we could get the long hike down to the river done before the day grew too hot. I could say that the hike was easy, being all downhill, but it wasn’t. Its 8 miles, dropping 4380 feet to the river. It is steep in some places, with some exposure as we traversed the cliffs. Fortunately, there are rest stops along the way, with shelter, water and rest rooms. This is civilized hiking, unlike the other primitive trails that explore the Canyon, from rim to river or along the broad platforms and mesa’s.

I had come down the river from Lee’s Ferry to Phantom Ranch on a college spring break trip nearly 45 years earlier, so I felt I was just picking up where I’d left off. I was curious to see what had changed over that time. The shelters along the trail are one change. Forty-five years ago the only real shade and water for the hiker was at Indian Gardens, 3000 feet below and 4.8 miles from the South Rim. Even going downhill, it can be a taxing hike in hot weather. And then there is the hike back up for those not continuing down the river.

We met the boats at Pipe Creek boat landing, where we had lunch, stowed our gear and got underway. Just down the river was the first big rapid, Horn Creek, and our “baptism” in the waters of the Grand Canyon. More big rapids followed the next day; Granite, Hermit and Crystal. All were run expertly by our guides, avoiding the dangerous holes and ledges, and soaking us to the skin.

The days ran on unaccounted, as often happens on long river and wilderness trips. It didn’t take long to forget what the day or date was. The sun rose and set on a routine of camp, cooking, hiking and rafting, all to the ever present sounds of the river and canyon. Canyon Wrens were with us all the time. There was the roar of rapids and on one occasion the loud crashing report of a rock fall above us, startling everyone as we set up camp. We had cool rainy weather for a couple of days, a soft soaking rain mostly that let the small side streams stay clear.

The hike up Stone Creek was magical, if wet, the light rain making the black rock glow. There were low clouds swirling around the tops of the mesa cliffs giving the canyon a surreal air rarely experienced in that desert landscape. Camp that evening beneath the Owl Eyes was soggy. Wet sand tracks into tents and sleeping bags more than dry sand. Even so everyone was cheerful and glad simply to there and see the Canyon in a different mood than normal.

Heavier rains came toward the end of the storm and neither the streams nor the river stayed clear for long. While stopped at Deer Creek some went for a hike above the slot canyon while others, myself included, stayed at the river to fish and take photos. There is a lovely waterfall spouting out of the very narrow canyon above the creeks confluence with the river. Clear, cold water was pouring out into a small pool and then the river when we arrived. Rainbow trout held in the eddies that shared the mix of this water alongside the rocky bank of the main river. For a while the fishing was good, but that changed quickly when the falls and creek grew red with the noise and volume of a flash flood. The muddy torrent poured into the placid pools and eddies, turning everything opaque with mud as the currents mixed. That and other side channel floods put an end to fishing for the rest of the trip.

It sudden flood on Deer Creek was also scary for those who had hiked above the falls. It came on them quickly, forcing the group to wade through a larger, muddier and less placid stream than they’d forded on the way up. Wading a small clear flow of water is one thing, wading the same stream in a higher, angrier mood is another.

It seemed as if the storm might be lifting, but later that evening at the Pancho’s Kitchen camp an evening thunderstorm rolled in with more rain and lots of wind. More mud and rock tinged floods came in after that in drainages coming down the north rim side of the canyon. The next morning the Colorado River was in its original red color and stayed that way for the remainder of the trip.

We had other side trips, like a hike up Havasu Creek coming in from the south, where the water was still the pale mineralized blue that makes it and its falls famous. Kanab Creek, flowing in from the north, was as muddy and angry as Deer Creek had become the day before.

But the stormy weather passed and soon we were back under clear skies and hot sun. It’s always amazing to see how fast things dry out in that air, from tents to clothes to temperament.

The night sky, when clear, was spectacular. There is no outside light in the Grand Canyon to mask the millions of stars overhead. Lying in a sleeping bag, watching the show of stars, milky way and meteorites as they slowly circle the pole is one of the most amazing and special sights in the Canyon. The Milky Way seemed especially bright, vibrant and clear. For many full glory of this starry skyscape is new and unexpected. People are used to the few stars that urban light pollution will let through, and far too many folks have only seen the Milky Way in pictures.

Lava Falls is one of the high points of any trip through the lower Grand Canyon. On this trip the river flows seemed a bit higher than the guides would have preferred, but there is no other option than to take the boats down through that storm of white water. It is one of the impressive cataclysm of water and rock on the continent, even though it only drops 13 feet according to the guide book. Other rapids have greater drops, and Crystal perhaps a deeper hole, but none have the combination of forces that make such a maelstrom as Lava Falls. It is the most intense 20 second ride of your life. It is something no amusement park or imitation experience imitate. I’ve rafted with many “bucket boats” over the years but have never had one so full of water as we had at the bottom of Lava Falls.

The rest of the trip out was anticlimactic, adrift through the final miles of our time on the river. We camped the last night where we would be lifted out by helicopter to the Bar 10 Ranch early the next morning. From there we flew to Boulder and then by bus to Las Vegas. The culture shock of transition from the natural reality of the Canyon to a man-made imaginary reality of glitter and entertainment was jarring. There is no greater contrast than that between the high walls, river, light and sky of the Grand Canyon and the noise, crowds and neon of Las Vegas.

Yet for many people the “reality” of Vegas is more “real” than that of the Grand Canyon. The lower end of the Canyon above Lake Mead has become a corridor of helicopters and jet boats, ferrying hundreds of people for a two hour “tour” of what they think is the real Grand Canyon. On busy days as many as 450 helicopter trips are made in one day. On the short flight out I counted at least ten helicopters heading east for the Canyon, almost in formation, like a scene from Apocalypse Now.

Quite time and solitude, with only the call of the Canyon Wren and the constant song of the river is something these helicopter tourists never experience. Only the noise of the engine competing with the insipid music of an uninspired narrative in the headphones provides background for what they are seeing. The trip is quick, efficient and undoubtedly profitable. But it is not in any sense an experience of the Grand Canyon.

Now developers hope to replace real experience of the Grand Canyon with a similar brand of imitation tourism on the eastern side of the Park. They want to do it with an effortless ride down to the confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado Rivers.

The confluence is a place sacred to all of the tribal cultures of the southwest. It is the place of origin, of emergence and beginning. Currently this place can only be reached by floating down the river from Lee’s Ferry or by an arduous hike from the rim. Either way takes effort and time, two vital ingredients for any experience of wild places like the Grand Canyon.

The proposed development would create a massive “village” of hotels, restaurants and gift shops on the rim, on land ceded to the developer by the Navajo tribe. The most outrageous insult would be a gondola and walkway to carry people to the rivers and confluence. For a price you can get a non-experience experience, with little or no effort or time. Check off the Grand Canyon and move on to the next “attraction”.

I noted at the beginning of this essay that it goes without saying that the Grand Canyon is a special place. So why say it? Because some people take it for granted, seeing it only as an opportunity for profit as they do with places like Niagara Falls. But the Grand Canyon is special in ways that we can’t describe without knowing it as it is, on its terms, with a sacrifice of time and effort. That is how people need to experience the heart of the Canyon, not through a manufactured “experience”. The Grand Canyon is not and should never be allowed to become a theme park. It is sacred, in the full and true meaning of that word. As Theodore Roosevelt said, “Leave it as it is. You cannot improve on it. The ages have been at work on it, and man can only mar it.”

We owe it to the future, and the experiences of nature and wonder our heirs will need, to heed his advice.

This guest post by Mindy Roberts and Danielle Shaw from Washington Environmental Council is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Green-Duwamish River.

Imagine you are a salmon looking upstream in the Duwamish Waterway.

You hatched from the gravels of the Green River several years ago, grew to several inches, and swam downstream through Elliott Bay and on to the Pacific Ocean. Now you’re back to complete your life cycle. Your ancestors thrived in the cold, clean water, and many sustained the people who lived in the region. Today, your waterscape is far different, and fewer of you survive.

The Green-Duwamish faces a range of threats as it runs from the Cascades through the developed lands around Puget Sound. Generations of people harvested forests, grew food on agricultural lands, built homes and roads, and industrialized lands to serve our needs. We did not understand the negative impacts our actions had until things we value, like clean water and salmon, declined. Fortunately, millions of dollars and decades of work have been invested to clean up our legacy of industrial pollution, and we are slowly seeing improvements. Now we face modern threats that could undermine this tremendous investment.

Today, polluted runoff is our biggest source of toxic pollution in Puget Sound. Car fluids, pesticides, dog poop, cigarette butts – all those remnants of our day to day activities – are left on the pavement and swept up by the rains heading straight for rivers, lakes and streams.

Highway runoff kills Coho salmon. Salmon are not only a cultural icon of the Pacific Northwest, but a major food source around here, especially for tribes and immigrant communities living along the Green-Duwamish. Polluted runoff threatens our iconic salmon runs, our vibrant economy, and the health of our communities. The more we build out and pave over the natural landscape, the more pollution we’re sending straight to the Green-Duwamish River.

Rain gardens adjacent to South Park Bridge crossing the lower Duwamish help treat all the road runoff for the west side of the bridge. | Natalie Jamerson, Washington Environmental Council

The Puget Sound region largely developed without stormwater controls because we did not understand the threat of polluted runoff. In the Green-Duwamish, uncontrolled runoff from our developed lands can also cause flooding and erosion, along with the toxic contamination.

Here at Washington Environmental Council, we think a lot about clean water, polluted runoff, and better solutions. Study after study has shown that low-impact development approaches and green infrastructure are far better than pipes and drains at managing polluted runoff and protecting our waters.

To save the Green-Duwamish, we must tackle our stormwater problem. This requires a coordinated effort to avoid the mistakes of the past as new development serves a growing population. We must also figure out how to address the biggest source of the problem: our already built out areas currently receiving no stormwater treatment.

Mindy Roberts and Danielle Shaw from Washington Environmental Council

Mindy Roberts and Danielle Shaw from Washington Environmental Council

Mindy Roberts and Danielle Shaw both work for the People of Puget Sound Program at Washington Environmental Council. Washington Environmental Council is a nonprofit, statewide advocacy organization that has been driving positive change to solve Washington’s most critical environmental challenges since 1967.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has once again turned its back on the opportunity to help prevent stormwater runoff from polluting local waterways.

In September 2015, American Rivers and its partners Natural Resources Defense Council, Blue Water Baltimore, Clean Air Council, and Los Angeles Waterkeeper filed petitions with the EPA urging them to use the power granted to them by the Clean Water Act, to protect local waterways from stormwater pollution from commercial, industrial, and institutional (CII) properties. This power is known as residual designation authority (RDA).

Commercial sites tend to generate a significant amount of pollution due to their large impervious surfaces such as paved parking lots and rooftops. The most common pollutants that run off from these sites are sediment, nitrogen, phosphorous, zinc, and copper. These can damage the water quality for local rivers and streams.

RDA can be used by EPA when they determine that a category of stormwater discharge is contributing to water quality violations. Once that determination is made the EPA must require those dischargers to apply for permits to address the polluted runoff coming from their site. The petitions filed were for the Army Creek watershed in Delaware, the Back River watershed in Maryland, the Los Cerritos Channel watershed in California, and the Dominguez Channel watershed in California. All of these watersheds are degraded by pollutants coming from stormwater.

How Polluted Runoff is Affecting These Areas

Back River, Maryland

When it rains in Baltimore, pollution such as sediment, nutrients (phosphorous and nitrogen) and other waste washes off of impervious surfaces and into the Back River. This stormwater pollution is one of the major reasons that the State of Maryland and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) have declared the Back River, which runs through Baltimore City and County and empties into Chesapeake Bay, too dirty for recreation, fishing, aquatic life, and wildlife uses. Within the Chesapeake Bay watershed, polluted runoff impairs 1,570 miles of streams and contributes to the sediment, phosphorous, and nitrogen loads of the Bay.

Commercial, industrial, and institutional sites occupy more than 20 percent of the land area that drains into the Back River. These sites account for one-third to one-half of all nutrient and sediment pollution that reaches the Back River. These sites triple the pollutant loadings that the Back River would receive from the entire watershed under natural conditions.

Army Creek, Delaware

When it rains in New Castle County, Delaware, pollution such as phosphorous and nitrogen along with other wastes washes off of impervious surfaces and into Army Creek. This stormwater pollution is one of the major reasons that the State of Delaware and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency have declared Army Creek, which runs through New Castle County and flows toward the Delaware River, too dirty for recreation, fishing, aquatic life, and wildlife uses.

Commercial, industrial, and institutional sites occupy more than 30% of the land area that drains stormwater into Army Creek. These sites account for more than one-third of all nutrient pollution that reaches Army Creek. These sites triple the pollutant loadings that Army Creek would receive from the entire watershed under natural conditions.

Los Cerritos Channel and the Dominguez California

When it rains in Los Angeles, California, pollution such as zinc, copper, and nitrogen along with other wastes washes off of impervious surfaces and into local waterbodies like the Los Cerritos and Dominguez Channels. This stormwater pollution is one of the major reasons that the State of California and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency have declared the Los Cerritos Channel and the Dominguez Channel, which run through Los Angeles and empty into the Pacific Ocean, too dirty for recreation, fishing, aquatic life, and wildlife uses.

Commercial, industrial, and institutional sites occupy more than 30% of the land area that drains stormwater into the Los Cerritos Channel and Dominguez Channel watersheds. These sites account for approximately 30% of the zinc loadings, 20% of the copper loadings, and 25% of the nitrogen loadings in the Los Cerritos Channel and 80% of the zinc and copper pollution that reaches the Dominguez Channel. These sites quadruple the pollutant loadings that the Los Cerritos and Dominguez Channels would receive from the entire watershed under natural conditions.

Taxpayers Left Paying the Bill for EPA Inaction

EPA lost an opportunity to require commercial, industrial, and instructional property owners to control stormwater on site with proven, cost-effective green infrastructure practices that will add benefits to the surrounding community. Instead EPA is leaving these municipalities to pay for the clean-up of polluted runoff that is produced on private property.

American Rivers and our partners will keep working towards a solution to reduce polluted stormwater runoff in these watersheds.

This post by American Rivers’ Lapham Fellow, Jonathon Loos, is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Green-Duwamish River.

The Green-Duwamish River is an interesting study in how the character of a river system can change across a landscape. Originating as snowmelt flowing off the Cascade Mountains, and encompassing some of the United States’ last remaining salmon runs, the wild charisma of the headwaters is palpable. That same river also flows downstream through one of the Northwest’s most populated regions, meeting the Puget Sound amidst the iconic cityscape of Seattle, Washington. The Green-Duwamish is both a wild and an urban river. This duality showcases the Green-Duwamish’s unique character, and the multifaceted pressures it faces.

Focusing on Critical Threats

A system that varies in character, such as the Green-Duwamish, faces a myriad of issues— on one hand there is a need to preserve its wild character, and on the other hand there is a need to improve the sustainability and vitality of a highly impacted system. Each issue presents such compelling challenges; it is difficult to determine a specific point on which to raise the alarm. For example, the lower Green-Duwamish faces dual-pronged water quality impairments, while in the upper Green, fish run into dams as they strive to complete essential migrations to and from the sea.

Fortunately, there are some fiercely dedicated stakeholders working on each of these issues, most of whom have the Green-Duwamish River right in their backyards. If you talk to any one of them, they will tell you how important addressing each of these threats is to restoring the Green-Duwamish. Furthermore, they’ll tell you that fixing any single problem will not stop degradation of the river nor recover its dwindling salmon populations. Instead, many stakeholders acknowledge that efforts to restore the Green-Duwamish’s health and function will only be fully realized when all of these challenges are addressed in unison. This approach will require proactive efforts across the entire watershed, beginning with mindful citizens and supported by local municipalities, state agencies, federal agencies and the U.S. Congress.

Over the course of the next few weeks, American Rivers’ blog will feature the perspectives of individuals with personal ties to the Green-Duwamish, as well as key actors working to restore the river and its native salmon populations. While the threats facing the Green-Duwamish are numerous, the objectives in addressing them are clear: restore water quality and remove barriers within the watershed. Here’s a quick overview of those issues, all of which will be discussed in more detail by on-the-ground experts in the coming weeks:

Toxics and Temperature

The Pacific Northwest is known for its precipitation. In urban areas, rain becomes stormwater runoff, and can wreak havoc on aquatic ecosystems. Urban runoff flushes pollutants that are toxic to fish and wildlife into creeks, streams and rivers. The Green-Duwamish receives high loads of these pollutants, creating toxic water quality conditions that harm native fish. The lower Green-Duwamish also flows through densely developed urban areas with simplified river channels and riverbanks stripped of shade-providing vegetation. Lacking deep pools and without enough shade, waters heat up during summer months, reaching temperatures that are harmful, or even lethal, to salmon migrating upstream.

Obstructed Migration

Fish that make it past harmful toxic and thermal conditions in the lower Green-Duwamish face a different set of hurdles as they move upriver. Two dams, the Tacoma Diversion and Howard Hanson Dam, block upstream passage of migrating adult salmon. Both dams have been equipped with passage facilities to move fish upstream. However, Howard Hanson Dam still lacks the capacity to move juvenile fish back downstream to spend adulthood in the Puget Sound. This is the current scenario in the Upper Green; even when spawning adult salmon survive the journey through polluted and warm waters, and make it over two dams to reach spawning habitat, their offspring cannot make it back downstream.

The National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) and the Army Corps of Engineers have been working diligently to finalize a project design for implementing downstream fish-passage at Howard Hanson Dam. However, the costs associated with this project are much higher than the amount that was initially authorized for construction of Howard Hanson Dam by the U.S. Congress. To secure the funds needed to implement downstream passage will require another approval by Congress. We need strong support to make the final push for this to happen.

Making the Case for Restoration

Many people throughout the Green-Duwamish watershed recognize that this system possesses incredible natural, cultural and economic value. Communities and agencies are galvanizing along the banks of the Green-Duwamish to invest in actions that restore the river and sustain its shared resources. Those efforts will never reach their full restorative potential as long as downstream fish passage remains blocked at Howard Hanson Dam. Congressional approval of the plan to implement that passage is vital to moving forward with restoring the Green River, and will signal to local, regional and state governments that healthy, ecologically functioning watersheds are worth investing in and protecting.

Dams fail. It’s inevitable and it’s happening now.

Just recently, Hurricane Matthew caused widespread flooding and more than 20 dam failures in North and South Carolina.

Rewind one year to October 2015— same place, different storm. One out of every 50 dams regulated by the State of South Carolina failed (plus hundreds of unregulated dams). This was the second most costly environmental disaster in South Carolina’s history — $12 billion. And more devastating than the financial cost is the loss of life (so far 59 people in the U.S. between the two storms) and destruction of homes and businesses (more than 1 million structures destroyed in Hurricane Matthew).

Fast forward to early October 2016, thousands of people have been evacuated from their homes due to the threat of dam failures in North Carolina. Plugging a hole the size of a truck will require more than a little duct tape.

Part of the problem is that we aren’t thinking ahead. Many dams look very formidable. Big walls. Strong. But concrete breaks down over time, especially when subject to the forces of nature. So does brick and mortar. And earthen dams? No doubt.

We need a commonsense approach to managing our infrastructure.

Why do dams fail?

Dam failure can result from any number of issues, including: inadequate spillway design, spillways blocked by debris causing dam overtopping, land use change causing increased runoff, outdated technology and design, changing weather patterns that alter flow rates, defects in the dam’s foundation, settlement of the dam crest, internal erosion of the dam caused by seepage (this can happen around pipes, animal burrows, plant roots, other cracks), structural failure of the materials used in dam construction, and/or inadequate maintenance of the structure.

Dams are deteriorating faster than they can be repaired. According to the Association of State Dam Safety Officials, the cost to rehabilitate our nation’s dams would be more than $70 billion (high hazard dams alone would cost $18.2 billion to rehabilitate).

Meanwhile, state dam safety offices are historically underfunded with a limited number of staff responsible for inspecting hundreds of dams. This tends to result in a focus on only those larger structures that pose a higher risk to life and public and private property should they fail. Smaller structures may be inspected infrequently, if at all, creating a threat to public safety. While many of these dams are “low hazard,” that is not the same as no hazard. Failure of small dams has been known to wreak environmental damage and cause significant downstream damage to things like driveways or roads.

There are also social behavior issues surrounding dams, which confound safety concerns. People seem to love to play on, in, and around dams. Paddling, fishing, swimming, sunbathing. It all seems fun until you get sucked into the hydraulic undertow.

This is a huge problem. How can we begin to tackle it?

There are tens of thousands of dams around the country that no longer serve the purpose they were built to provide and whose removal could eliminate the cost and liability associated with owning a dam. Unless they are well maintained, their condition only gets worse every year. The most cost-effective and permanent way to deal with obsolete, unsafe dams is to remove them.

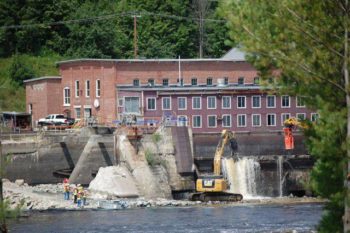

Whittenton Dam removal pre-construction meeting, Mill River, Taunton Massachusetts, July 13, 2013 | American Rivers

We support modifications to state dam safety programs that increase dam owner responsibility for dam inspections, as recommended by the Association of State Dam Safety Officials. States that have adopted this approach have been able to ensure that more of their state’s outdated and deteriorating dams have safety inspections and that dam owners follow up on the results of those inspections by repairing and maintaining their dams. Owners of dams that no longer function as intended may also find removal more beneficial than the cost of ownership.

Recently, U.S Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell highlighted the critical need to remove obsolete dams to improve the safety of our nation’s rivers. In recent years, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) has expanded their technical assistance capacity in some regions, partnering with local groups like American Rivers in the Southeast to provide design and deconstruction assistance on dam removal projects. This effort has grown from a series of small demonstration projects to what is now a highly capable, trained team of demolition experts within the USFWS who are now able to take on a wider diversity of dam removal projects.

Collaborative public-private partnerships like this are incredibly important if we are ever to address the massive number of obsolete dams still clogging our nation’s rivers. Increasing the capacity of federal agencies to actively engage in projects helps to reduce the ultimate cost of removal and increases our ability to address the backlog of problem dams.

Ensuring strong state and federal programs for removing outdated dam infrastructure is a commonsense approach for eliminating hazards, increasing resiliency in vulnerable areas, and restoring our rivers for the people, fish, and wildlife that rely on them.

Duke Energy’s Buck coal plant sits on the banks of the Yadkin River in central North Carolina just off Interstate 85, about fifty miles upriver from the head of the Pee Dee River, one of America’s Most Endangered Rivers® for 2016.

The Yadkin is endangered by five million tons of Duke Energy’s coal ash sitting in one hundred and seventy acres of unlined pits towering above the river’s banks. In a settlement between Duke Energy and environmental groups in early October, that ash will be excavated and recycled for safe use in concrete.

These coal ashpits are part of the Buck Steam Station, named for James Buchanan “Buck” Duke. The coal plant was built in 1926 and burned coal for four score and seven years, until 2013. In the 1950’s Duke began storing the ash left over from the coal combustion process in a series of unlined pits held back from the river by a series of earthen dams. On the other side of those ponds was a small rural community, of houses on well water, named Dukeville. Today, Duke’s own engineers assess that the site leaches over 70,000 gallons a day of contaminated groundwater a day into the Yadkin River.

Yadkin Riverkeeper first began investigating the Buck site in the spring of 2014, after they were first responders on the Dan River spill where a broken stormwater pipe at a Duke Energy facility in north-central North Carolina shot tens of thousands of tons of coal ash into that river. As we investigated two things became clear very quickly: The dams that were supposed to hold back the coal ash leaked and residents on well water next to the site had high levels of contaminants associated with coal ash in their wells.

Yadkin Riverkeeper filed state and federal lawsuits against Duke Energy in 2014 to force the clean up of these leaking unlined pits to protect the river and groundwater surrounding the site. In October 2015, a federal judge ruled that those suits could go forward because the state of North Carolina was not diligently prosecuting water quality issues at the site.

In the spring of 2015 over seventy families in Dukeville received letters from the state of North Carolina telling them not to drink their water. Then, as a part of our lawsuit, it was revealed that the governor’s staff had called the state toxicologist to the Governor’s mansion and pressured him to change those recommendations. Then the Governor’s chief of staff accused the toxicologist of lying under oath. Then the state epidemiologist, the toxicologist’s boss, resigned in protest, defending her staff and saying that the Governor’s administration was “misleading the public”.

Through all this, families around coal ash sites across the state have been living on bottled water provided by Duke Energy since that time and are now required by state law to receive municipal water or house filtration systems by 2018.

Our hope is that Duke Energy’s choice to excavate and recycle the ash at Buck will be an example to other utilities across the country that are studying what to do with their own ash. They have the chance to take proactive action and avoid ending up, as Duke did, pleading guilty to federal Clean Water Act crimes and being fined $102 million dollars by the federal government.

We hope other utilities will not have to suffer half a billion dollars of divestment and blacklisting by the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund because they do only the minimum that the law requires to protect neighbors and rivers. Duke Energy suffered this indignity just a month ago, in September of 2016, after Waterkeeper Alliance members told the story of neighbors living on bottled water around Buck Steam Station to the Norwegian Parliament’s Council of Ethics, who specifically censured Duke for their handling of coal ash in North Carolina.

The painful example of North Carolina’s coal ash fight may show a better way. If utilities across the country take proactive steps to protect neighbors and rivers it will bring our nation’s coal power era to a close with dignity.

In the end what we saw at Buck was neighbors, environmentalists and investors telling utilities saying the same thing in different ways: protect our wells, rivers and portfolios from coal ash contamination.

Will Scott, Yadkin Riverkeeper

Will Scott, Yadkin Riverkeeper

Yadkin Riverkeeper’s mission is to respect, protect and improve the Yadkin Pee Dee River Basin through education, advocacy and action. It is aimed at creating a clean and healthy river that sustains life and is cherished by its people. For more information, visit YadkinRiverkeeper.org

Guest post by Willie Dodson is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Russell Fork River.

The best cup of coffee in Southwest Virginia won’t be found in a fancy cafe in some college town, and it won’t be served by a twenty-something with those big things in their ears. I have nothing but love for the Ugly Mug in Wise, Zazzy’s in Abingdon, and my old haunt Bollo’s over in Blacksburg. Each of these shops makes a mean cup that will put a pep in your step and bring peace to your addicted soul. But if you really want a coffee experience to write home about, you’re going to have to go to Haysi up in Dickenson County, Virginia, on the Russell Fork River and find Gene Counts.

Russell Fork River

Gene is a retired public school teacher and administrator, a Haysi native, and an active and outspoken advocate for the Russell Fork River. If there’s anything he’s more enthusiastic about than coffee, it’s the river. In his seventies, the dude is still out there in his kayak, tearing through the set of Class V rapids with names like Fist and El Horrendo, that draw hundreds of other whitewater nuts like him to the Breaks Interstate Park every year. Here at the park, just about six miles from Haysi as the crow flies, the Russell Fork cuts a deep and winding canyon through the mountains, surging from Virginia into Kentucky.

One late August afternoon, I paid Gene a visit to talk about his organization, the Friends of the Russell Fork, and about past and ongoing efforts to protect, improve and promote the river. Per his request, I make a habit of bringing my banjo with me when I visit. I sit at the kitchen table and frail out old tunes while Gene fusses around with an assortment of barista gadgets, crafting my coffee like it’s an art and a science. I’ll say it again. It’s the best cup of coffee in Southwest Virginia.

When the jam session ended (me on banjo, Gene providing the gurgle and hum of the cappuccino machine), I asked him to tell me about the birth of the Friends of the Russell Fork. As many a good storyteller is prone to do, his answer started with a prequel, “Well, in a way, it began when I was a child. My father was a union organizer. I remember riding around with him to all these little coal camps around here organizing for the United Mine Workers of America.” This experience of growing up in a union household instilled in Gene a belief that change is possible when people work together. He described how much he respected and looked up to his father, and how this aspect of his old man’s life inspired him to walk a similar path.

Breaks Park along the Russell Fork River

When strip mining started up in the 1960’s, Gene became a vocal opponent of the practice. “I was quick to argue,” he said. “These strip mines that you see around here, I fought them!” He eventually joined with a regional social and environmental justice organization called the Council of the Southern Mountains, and traveled to Washington, D.C., to meet with Robert Byrd (at the time a Congressman from West Virginia and eventually a Senator) and other legislators to push for the establishment of firm restrictions around the practice. The fruits of this labor would later bear out as the 1977 Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act.

Shortly thereafter, Gene had to take a step back from activism in order to focus on his career in the public schools where practically all of his students were the children, grandchildren, nieces and nephews of miners and others who worked in the coal industry. Throughout this time that Gene’s activism took a back seat, his convictions persisted, and his love affair with the Russell Fork grew ever deeper. In the latter part of his working years, he began to envision a new grassroots project. Gene stated, “Back in the 1990’s, I started thinking of a group that could help us back here to go into these mountains and put in some hiking and biking trails to attract tourism. I knew that the future of this county wasn’t minerals. It was gonna be tourism.”

White water kayaking on the Russell Fork | Leland Davis

He discussed the idea with friends, other local leaders, representatives of the Breaks Interstate Park, and members of the Great Eastern Trail Conference (an effort to establish a hiking trail from Northern Alabama to the Finger Lakes region of New York State). Over time a consensus was found, grants were secured and a board of directors was formed. The Friends of the Russell Fork emerged as a locally-led organization dedicated to water quality protection, environmental education, and the promotion of the Russell Fork as an ecological treasure and an economic engine for the area.

It’s difficult to pinpoint a specific start date for the organization, as the networking, fundraising and projects that would become Friends of the Russell Fork began to manifest years before the group was officially chartered. It is safe to say, however, that in one form or another, FORF (pronounced just how it looks), has been a leader in environmental education, conservation and service in the area for well over a decade. The organization has provided a book about the natural and cultural history of the Russell Fork watershed to every ninth-grader in the county. They’ve partnered with AmeriCorps VISTAs to survey over 200 homes within the watershed for straight pipes (a plumbing design that results in untreated sewage entering into waterways), faulty septic systems and other potential sources of bacterial contamination to make this information available to state agencies charged with eradicating such point sources of pollution.

A view of the Russell Fork River from Breaks Park

Bacterial pollution is only one of the threats the Russell Fork has faced. Extractive industries, such as coal mining and more recently natural gas drilling, have contributed pollution in the form of sediment and metals. However, it’s important to note that while Gene himself has been an outspoken critic of strip mining in this area, it’s not an issue on which FORF has taken a position. Regardless, just a few miles upriver from Gene’s home, a company called Contura holds a disputed permit for an 1,100-acre mountaintop removal mine called the Doe Branch Mine. While state mining regulators have indicated their approval, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency maintains a hold on the project, as it is expected to cause further harm to the already impaired Russell Prater Creek, one of the primary tributaries of the Russell Fork.

“What concerns me is that we have absentee people owning this permit. If they go up there and start stripping, who knows what would happen to our Russell Fork watershed? They’re just about money. They don’t care about our environment,” said Gene.

These days, Friends of the Russell Fork is not as active as it once was. “What we need now is young people,” Gene said, as he got started weighing out precisely 16.1 grams of home-roasted beans for my second cup of coffee. “Our current board — we’re getting old. We need some new energy and new leadership from the young people in this area.”

Some local young folks are staying in the area and working to build a new economy that works for everyone. Meanwhile, the area’s abundance of outdoor recreation opportunities and just plain wilderness is drawing in new arrivals, so there’s hope yet that this river will continue to inspire new generations of caretakers. One easy way to speak up for the river now is to urge the Environmental Protection Agency to uphold its objection to the Doe Branch Mine permit.

Willie Dodson is the Central Appalachian Campaign Coordinator for Appalachian Voices. Appalachian Voices is an environmental non-profit committed to protecting the land, air and water of the central and southern Appalachian region, focusing on reducing coal’s impact on the region and advancing their vision for a cleaner energy future.

Willie Dodson is the Central Appalachian Campaign Coordinator for Appalachian Voices. Appalachian Voices is an environmental non-profit committed to protecting the land, air and water of the central and southern Appalachian region, focusing on reducing coal’s impact on the region and advancing their vision for a cleaner energy future.

In August, a member of the Navajo Nation Council submitted legislation that could authorize the construction of the Grand Canyon Escalade. The Escalade is a two million square foot, industrial-scale construction project on the east rim of the canyon that includes a tram to the bottom of the Grand Canyon at the confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado rivers. Picture it: noise, trash, pollution, and 10,000 people a day on the tram and walkways. If the Escalade project were to move forward, this national treasure would be forever scarred.

Over 100,000 people have voiced their opposition to this shortsighted proposal, amplifying our message of protecting the Grand Canyon.

On October 10, the Navajo Nation Law & Order Committee unanimously voiced their opposition to the Escalade proposal. The Navajo Historic Preservation Office also issued a position statement strongly opposing the Escalade development.

This is great news but it is just the beginning.

Here’s what happens next

The legislation will continue to work its way through the Navajo Nation Council, much like a bill might proceed in the United States Congress. The bill will go through discussions in three additional committees over the coming weeks before it is sent to the floor of the Navajo Nation Council for a full vote. Two-thirds majority is needed to override the president of the Navajo Nation, Russell Begaye, who said he would veto this proposal.

While we wait for the legislation to make its way through the Council, there are members of the Navajo Nation, most notably the local Navajo families comprising Save the Confluence, working to ensure the project never sees the light of day. They must hear our voices of support. There’s still time to help.

Here’s what you can do:

- Encourage your friends, family, and community members to join you by signing the petition, too. Send them this link: http://americanrivers.org/grandcanyon

- Share your stories of why you feel the Canyon is grand. Let us know what it means to you, and show your support for protecting this awesome wonder. Tell your story here.

- If you’re on Facebook, follow American Rivers and Save the Confluence for the very latest developments. #WeAreGrand

Thank you for your help protecting this national treasure.

I always say I want to hang out with Hal and Ricky, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service dam removal folks, as much as possible, and it isn’t only because they are great people. Hanging out with Hal and Ricky means that the hard part of my job – getting a dam removal project ready for demolition (fundraising, permits, design, coordination, etc.) – is done. Last week, Granite Mill dam on the Haw River was ready to meet its end. Thanks to our partners, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, for their dedication, high quality of work, and shared joy for making rivers run freer.

American Rivers was happy to partner with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to remove the Granite Mill Dam. | Steve White

The dam backstory: The Granite Mill dam was built and rebuilt several times on the Haw River in the Cape Fear River basin in the Town of Haw River, NC, in the 1800s to power area industry. Before demolition started, only remnants of the dams were left that created a public safety hazard and negative impact to river health.

Why remove the Granite Mill dam?

- Improve recreation

- Improve public safety

- Stimulate local river based economy

- Improve river health

Granite Mill Dam during de-construction. | USFWS

A local perspective: Joe Jacob with The Haw River Canoe and Kayak Co. told American Rivers, “We would love to put more folks on the stretch of river, but cut back because it was such a bad and unsafe put-in. Our guests were getting pinned all the time. It hasn’t been a good place for beginners to start paddling. [After the dam is removed], we will start putting more folks on that stretch of river. Thanks for making that possible.”

This dam removal adds to other efforts by American Rivers in the Cape Fear River basin like the removal of the Upper Swepsonville dam in 2013. The Cape Fear River is home to the federally endangered Cape Fear shiner, a fish only found in the Cape Fear River basin.

Want more? To learn more about how dams affect rivers, check out this blog: https://www.americanrivers.org/threats-solutions/restoring-damaged-rivers/how-dams-damage-rivers/

Right now, American Rivers is soliciting nominations for our annual list of America’s Most Endangered Rivers®. Do you think that your favorite river is facing a critical decision in the coming year? Have you been wondering… why isn’t my river on the list when it faces so many threats? Let us know!

Hopefully, you have seen our blog posts in recent months talking about threats facing the 2016 listed rivers. We are spreading the word about threats to these special places, thanks to you! Since April, our America’s Most Endangered Rivers blog series (scroll to the bottom of each river page for links) has covered the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint River Basin, St. Lawrence River, Merrimack River, Smith River, and currently the Russell Fork River. [Next up for mid-October: Green-Duwamish River in Washington.]

We are excited to announce that we are now accepting nominations for our 2017 report. Nominations are welcomed from any interested groups throughout the United States.

Rivers are selected based upon the following criteria:

- A major decision (that the public can help influence) in the coming year on the proposed action

- The significance of the river to human and natural communities

- The magnitude of the threat to the river and associated communities, especially in light of a changing climate

The report highlights ten rivers whose fate will be decided in the coming year, and encourages decision-makers to do the right thing for the rivers and the communities they support. The report is not a list of the nation’s “worst” or most polluted rivers, but rather it highlights rivers confronted by critical decisions that will determine their future. The report presents alternatives to proposals that would damage rivers, identifies those who make the crucial decisions, and points out opportunities for the public to take action on behalf of each listed river.

Please help us make the most of this great opportunity in 2017 by nominating a river you think deserves to be included on our list. Deadline for nominations is Monday, October 31, 2016. Contact Jessie Thomas-Blate for more information.

25,000 pieces of trash. That was our goal.

We wanted to honor the 25th anniversary of National River Cleanup® with 25,000 pieces of trash. That is: 25,000 pieces of trash being taken out of our waterways by the American public. And that’s just what they did.

At the start of 2016, we decided we needed to do something big for the 25th anniversary of National River Cleanup. We set out to get more people involved in cleaning up their hometown streams and faraway rivers by pledging a simple task: to pick up 25 pieces of trash in 25 days.

Volunteers comb the banks of the Ashley River for trash.

Lowell George

We realized that not everyone lives near a river or stream, and not everyone has a group in their town organizing regular river cleanups. But, we also realized, river cleanups don’t need to be limited to rivers.

When a piece of trash is thrown out of a car window or dropped by someone walking down the street, it doesn’t always make it into a trash can. Then rain comes, or a strong wind or a kid looking to use a bottle as a soccer ball and a storm drain as a goal, and all of a sudden that trash is in our stormwater system. What many don’t realize is that our storm drains lead to our rivers. And more than 65% of Americans get their drinking water from rivers. Big problem.

In order to keep our drinking water, wildlife habitats, boating routes, and scenic views pristine, we all need to pitch in and keep our communities clean. That’s where the pledge came in.

So far, individuals across the country have saved over 29,000 pieces of trash from making it into our rivers. California is leading the pack with a whopping 3,825 pieces of trash collected, followed by Florida with 1,700. Most states are in triple digits, but a few are lagging behind (you know who you are).

And, it’s not just individuals taking a stand against trash. Companies like Plow and Hearth and ReUseIt have stepped up and challenged their employees to take the pledge. Once staff have collected their pieces, they’ve been encouraged to share their finds on social media. These companies are not afraid to get their hands dirty.

Yampa River Cleanup | Kent Vertrees

In addition to our ever-changing pledge map, we’ve started collecting trash photos and images of cleanup success in our virtual landfill. Anyone who uses the hashtag #RiverCleanup on social media outlets like Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and Vine while completing their pledge will get their photo automatically put into our virtual landfill. If you scroll through, you’ll see some crazy trash and some awesome people cleaning up their waterways and neighborhoods. The most common finds so far are bottles, cans, food wrappers, plastic packaging, fishing line, tires, and smiling volunteer faces.

All cheesiness aside, while it can be disheartening to see all the litter around us, we can’t forget about the thousands of individuals and local groups making a difference in their communities across the country to keep our rivers clean. If you haven’t yet, take the pledge. Let’s blow 25,000 pieces out of the water (pun intended)!

On September 27th, the Aspen City Council voted unanimously to move forward with a resolution to develop a 150 foot dam on Maroon Creek and a 175 foot dam on Castle Creek in the shadow of the world renowned Maroon Bells.

Moose in Maroon Bells Wilderness | Alex Butterfield

These dams would flood private property on Castle Creek as well as federally protected land in the Maroon Bells Wilderness, one of the most visited and photographed valleys in Colorado. American Rivers strongly encourages Aspen City Council to rethink its September 27th decision and vote to permanently cancel plans for these destructive projects.

Aspen does not need these dams for municipal water supply, climate resiliency, or for stream protection – now or at any time in the foreseeable future. There are several cost effective and environmentally sound alternatives that communities throughout the west are pursuing to meet future water demands while building community resilience to climate change, including enhanced conservation, water re-use, flexible water sharing agreements, innovative natural water storage solutions, limiting outdoor irrigation, targeted traditional storage, sustainable groundwater development, and increased in-stream flow protection. Climate change is very real and the Colorado River Basin will continue to feel its effect as much as any region in the world, but addressing the issue with a grossly outdated solution is the wrong approach.

Aspen’s own 2016 water availability report clearly shows that Aspen does not need these dams and clearly states that existing water supplies can meet Aspen’s future demands (to 2064) and protect instream flows on Castle and Maroon Creek without the need to store more water, much less the nearly 15,000 acre feet of water that would fill the two dams.

Maroon Lake, September 2016 | Patrick O’Sullivan

Constructing a pair of 15-story tall dams and flooding the Castle and Maroon Creek valleys would likely cost hundreds of millions of dollars, but the monetary price would pale in comparison to the damage the dams would do to the natural environment. The massive ecological impact of dams has been thoroughly documented. Over 80,000 dams in the United States have fragmented habitat, degraded water quality, led to the extinction of dozens of aquatic species, and continue to cause significant public safety risks – all at great cost to society. Additionally, recent studies show that dams may actually contribute to climate change by producing methane from the stagnant water. The national trend is to remove dams in places like the Maroon Bells, not build them.