Today’s post is a guest blog from Meg O’Neill and she teaches at the Utah International Charter School. She spent many years as an outdoor educator for Naturebridge in Yosemite and led trips for Outward Bound prior to pursuing her Masters in Education at Colorado College.

Many of us here in America are fortunate to have endless opportunities to get outside, explore the wild, and explore ourselves. We hike, we fish, we ride bikes, we raft rivers, we celebrate and appreciate nature’s bounty that does so much to entertain us, inform us, and give us places to escape and thrive. A multi-day trip to Utah’s southern desert is just one excursion that can encourage personal growth and development through challenge and adventure, as well as just be a whole ton of fun!

Earlier in my career, I was able to channel my enthusiasm for the outdoors as an outdoor and environmental educator. Now, as an instructor at the Utah International Charter School, I am lucky enough to work with amazing and unique young people every day. And what’s more, through our partnership with the Four Corners School, I am thrilled expose kids from around the world whose lives have found them relocated to the Salt Lake City area.

Many of my students have had little or no experience in the outdoors. Some have, quite literally, only seen the refugee camp where they were born, one airplane, and their new neighborhood in Salt Lake. As a part of my role, I get to expand their horizons and provide new and formative experiences to these budding young people who represent not only the unique values of multi-culturalism, but are a core component of a rising generation of Americans. Recognizing the value of environmental protection, and the magic of wilderness, is imperative for these future citizens.

This year, my 7th and 8th grade students come from 16 different countries. Some were born here in the U.S.; others have come to Utah from places as diverse as Somalia, Mexico, Tanzania, Burma, Eritrea, Thailand, Rwanda, India, Kenya, Jordan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Syria, Cameroon, El Salvador, and Ethiopia. Truly a melting pot of international experiences and cultures plopped in the middle of a vast new country.

With adventures like a four-day San Juan river trip, or excursions to one of Utah’s signature National Parks, students get to explore topics like ecology, geology, biology, and meteorology that all come alive with extended time in the outdoors. They also get to practice their social language skills, and see their growth in effect in the real world outside the classroom. Wilderness experiences like these with Four Corners School foster collaboration and teamwork skills that serve my students in school and in life beyond.

The outdoors has inspired me, and millions of others across America, most of my life. My students also inspire and challenge me every day, and I am thrilled to be able to do the same for them.

For most of my adult life, I’ve been paying for stormwater. It doesn’t seem odd to me because communities need to pay to maintain water infrastructure. The cost relative to my other utility bills is pretty nominal. After looking at the price compared to other communities across the country, I’ve come to realize that what I pay for stormwater in Toledo, Ohio is at the lower end. But that’s me, someone who works in the clean water field and is aware of what stormwater is and what a fee might pay for.

So, what does the average Joe know about stormwater? What should they know? Are communities communicating effectively to the public about stormwater and the fact that they need to collect fees?

Storm events are increasing in frequency and severity throughout areas of the country including the Great Lakes basin, and the increase in rainfall is overwhelming our infrastructure. When rain falls in open, undeveloped areas not occupied by buildings or pavement, the water is absorbed into the ground and filtered by soil and plants. But, when water falls on roofs, streets, and parking lots, the water cannot soak into the ground. Instead, it enters the sewer system and it then has to be managed by municipalities and counties.

Stormwater goes from being the property-owner’s problem to the community’s problem really fast. And once it is the community’s problem, government agencies need to solve it.

To reduce sewer backups and urban flooding, communities need to ensure that more stormwater is able to soak into the ground, keeping it out of the overloaded sewers.

A “make and take” rain barrel workshop in Toledo, Ohio with the Toledo – Lucas County Rain Garden Initiative. | Katie Rousseau

We can reduce property and street flooding through a combination of gray and green stormwater infrastructure. Gray infrastructure refers to traditional engineered solutions to flooding problems, like sewers. Gray infrastructure is often designed to move rainwater to another location to reduce flooding. Alternately, green stormwater infrastructure practices treat water where it falls, allowing the water to sink slowly into the ground.

Whether they go gray or green, for many communities, stormwater infrastructure repairs are no longer a luxury; they are a necessity to reduce chronic flooding and improve impaired rivers and streams. Communities need to repair old systems and build new, modern systems that embrace technological advances from the last 100 years. But, communities also need money to do it.

A stormwater utility is an equitable way for communities to raise some of the money they need to fix the most immediate stormwater problems.

A stormwater utility is a fee charged to property owners—usually determined by the amount of impermeable surface on their property—that grants them continued use of the stormwater management system and ensures that system continues to function. Property owners—typically large land owners—can reduce their utility bill by implementing green stormwater infrastructure practices that reduce their property’s contribution to the stormwater management system. In this way, property owners are in control of their bills and their property.

Implementing a stormwater utility may seem difficult at first. Neither property owners nor government officials want to spend money on improvements that—in the best case scenario—no one ever sees. Infrastructure improvements and stormwater management are the kind of expenditures that only get attention when something goes wrong. Plus, local government leaders and stormwater managers are already short on time and resources, and educating the public about a stormwater utility can seem like an impossible task.

This is why American Rivers partnered with Bluestem Communications to develop a Stormwater Utility Communications Toolkit, which contains materials to ensure local leaders, city and county staff, and partners have the tools necessary to create a stormwater utility that is supported by the entire community. These tools are designed to give you the language and structure needed for jumpstarting a public engagement process. These tools are designed to be edited and personalized to fit your own community’s policies, values and personalities.

This toolkit contains:

- A stormwater utility overview and technical resources

- A strategy for building public support for a stormwater utility

- Sample outreach materials (Spanish versions available)

- Draft press release

- Social media posts

- Website language

- Tips for running successful public meetings

- Sample stormwater utility ordinance language

We hope that these tools are useful in your community as you advocate for, implement, or explore a stormwater utility.

I’ve been thinking a lot about stories, especially since November 9th. What stories do we tell each other? What stories shape us? What stories do we live?

A friend shared this blog and this line struck me: “We are entering a space between stories.” Ecotrust’s Spencer Beebe tells us, “We desperately need a new story, a new myth… We need a myth that celebrates community.”

Can rivers help us figure out what this new story needs to look like?

They are interconnected. They work best when they flow freely. They are dynamic, ever-changing. And water, it heals.

We need to write the story we want to live. We need to right the story, like righting a ship.

I have been thinking about the stories we tell at American Rivers, and how we need to do a better job being inclusive, to articulate the Why of what we do, why it matters. To everyone. How we need to do a better job reaching out and listening to others’ stories.

Our tag line is Rivers Connect Us. What does that mean? It means we all live downstream from one another and we’re all in this together. We are a nation of rivers.

Whether you want clean drinking water for your kids or the preservation of your cultural heritage, whether you want a neighborhood safe from flood damage and toxic pollution, or fish to catch or free-flowing rivers to paddle, we’re on the same team.

Our fall/winter newsletter and our annual report for 2016 celebrate connections. They celebrate people across the country who understand the importance of healthy rivers in their lives, and are doing their part for river protection and restoration.

People like Paul Bruchez, a rancher in Colorado who is working to restore the Colorado River so he has reliable water supplies. People like Maite Arce with the Hispanic Access Foundation who is rallying Latinos across the Colorado Basin in support of river conservation. People like Kasim Reed, the Mayor of Atlanta, who is championing green infrastructure projects that are good for the environment, community and economy. People like Burks Lapham who supports a fellowship program to develop the next generation of river conservation leaders, and people like Mark Deming of NRS who is proving business can be a force for good.

We’re going to tell more stories in the coming year. Stories that build bridges, that bring us together. And stories that illustrate very clearly what’s at stake when it comes to protecting our rivers, our clean water, our communities.

We’d love to hear your story. Why do rivers matter to you? Why are you standing up for rivers and clean water? You can share it here, and on social media with #WeAreRivers. Or email me.

Rivers have always been gathering places. They are where people first settled and traded. Villages and cities grew up at confluences. Rivers are where we gather around campfires to be with friends and family, to share some of the most meaningful experiences of our lives.

Let’s gather together. Let’s fire each other up. Let’s stand up for what we believe in and let’s write the story we want, the story we need. For rivers, and each other.

This post by American Rivers’ Lapham Fellow, Jonathon Loos, is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Green-Duwamish River.

In Western Washington, the Lower Green-Duwamish River has a severe temperature problem that is jeopardizing the sustainability of native fish populations.

The Green-Duwamish watershed is home to native populations of Chinook, chum, pink and coho salmon and steelhead trout. These fish use the lower river as a migration corridor when heading to the Puget Sound as juveniles, and again as adults returning upriver to spawn and reproduce where they were born.

This Green River Chinook salmon died before she could mate and lay her eggs. A pathology exam found evidence of a bacterial disease known to thrive in warm water. | Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission

Historically, the Green-Duwamish River supported populations of salmon large enough to feed generations of Native Americans. Today, this is not the case, as Green River Chinook salmon and steelhead populations have declined and are listed as Threatened Species under the Endangered Species Act. Unhealthy temperatures have likely contributed to the declines in native salmon stocks. Warm water holds less dissolved oxygen, which leads to stressed fish and promotes outbreaks of warm water-related bacterial and parasitic diseases in salmon and trout. These factors can create enough conditions to kill fish as they migrate upstream. Instances of pre-spawn mortality have been observed for Chinook; this is an enormous loss after salmon survive such a long perilous journey from egg to adult— from river to the ocean and back again.

Federal and state governments are tasked with defining healthy water quality standards for fish and people. The Washington State Department of Ecology defines the healthy maximum temperature threshold for the Lower Green River to be 63.5 °F. However, daily summer temperatures in the Lower Green River typically reach 70-72°F, and sometimes even exceed 74°F, a lethal temperature range for cold water fish like salmon and trout. In fact, in July 2015, the temperatures observed exceeded the lethal threshold at almost every mainstem location sampled in the lower 45 miles of the Green-Duwamish River (Green-Duwamish River 2015 Temperature Data Compilation and Analysis (Draft), King County).

Engineering Away Cold-Water Habitat

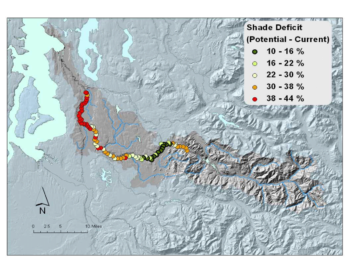

Much of the Green River is bordered by parking lots and asphalt trails. This figure shows the effective shade deficit by 1,000 m increments. The deficit is the difference between the mature riparian shade condition (i.e., lots of trees) and the current riparian shade condition (i.e., lots of roads and buildings). | Washington Department of Ecology

The Green-Duwamish’s heat problems are a consequence of development and flood-control infrastructure that has constricted the river channel. Over the past century, the Lower Green-Duwamish watershed has developed into a thriving hub of urban and industrial development. As a result, buildings have encroached on the river and squeezed out space for trees and riparian vegetation. Levees and concrete riprap have been installed along much of the Lower Green-Duwamish, intended to provide protection from floods and reduce erosion hazards. As river channels and floodplains are urbanized and engineered into controlled waterways, the natural processes that regulate a river’s water temperature become lost; riparian and forest shade is removed and cool groundwater exchange pathways are disrupted.

The middle and lower sections of the Green-Duwamish River need more shade. Development has led to few trees on riverbanks and increased water temperatures. | Washington Department of Ecology

Only a fraction of the lower 30 miles of the Green River has adequate riparian shade. Mature native trees, such as cottonwood, fir, maple, alder and willow, are cut down to accommodate levee construction and repairs. Rules set by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers restrict the growth of vegetation along levees and require their continual removal or pruning as they mature. While some trees have been planted to mitigate levee work, these plantings sit on benches that are often less than 10 feet wide— too narrow to support a robust shade-giving stand of trees and riparian growth. In an effort to comply with levee maintenance policies, local levee sponsors often remove planted trees before they mature.

As the influence of climate change intensifies, the Green-Duwamish’s degraded riparian habitat and harmful temperature conditions will persist or worsen until riverside management practices are changed. Salmon are resilient creatures, but they will not survive in the Green-Duwamish unless riparian shade is restored along the river.

What Needs to Happen

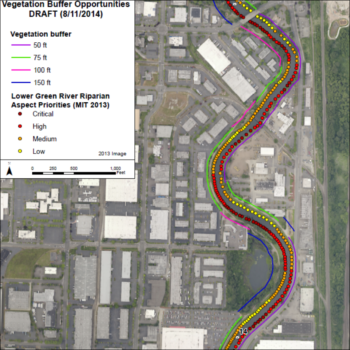

This is an example of a Sun Map, which shows potential vegetation buffer widths based on existing land use constraints. | King County, Washington

In 2011, the Washington Department of Ecology issued a call to action for local governments and citizens to help reduce water temperatures in the Green River watershed. The two top actions identified were: “Protect and restore streamside vegetation” and “Plant tree borders”. Unfortunately, very little action has been taken since the report was published five years ago.

Recently, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and King County have been working on the Green River System-Wide Improvement Framework— a plan to advance flood risk reduction in the lower Green River. As part of that effort, the Muckleshoot Indian Tribe Fisheries Division prepared “Sun Maps” to prioritize areas of riverbank where trees would be most effective in shading the river based on solar aspect (see Appendix G). That mapping effort was first completed in 2013 and presented a clear analysis of where shading is needed most. However, the combined influence of the Sun Maps, water quality regulations, and the listing of Puget Sound Chinook on the Endangered Species Act has not spurred the full level of action needed.

The King County Flood Control District, together with the cities of Kent and Tukwila, are choosing floodwalls and rip-rap bank armoring instead of sustainable levee designs that provide room for trees to shade the river. Image: Floodwall on Boeing Levee, completed 2013. | City of Kent, WA

King County hosts a grant program called “Green the Green” that promotes voluntary efforts by cities and private landowners to plant trees in riparian areas. However, funding for the program is lean and progress is likely to be slow unless the Green River’s health becomes a much higher priority for everyone, including the cities of Kent, Auburn and Tukwila, and the King County Flood Control District. Programs must be designed to encourage riparian landowners to maintain streamside buffers with native riparian vegetation and trees. Concurrently, new levee designs are needed that incorporate space for riparian buffers. This could be achieved through the inclusion of a wide and gently-sloped tree and riparian planting area on the riverside of levees, or by setting levees further back from the channel where possible.

Restoring riparian shading along the lower Green will not come at the cost of greater flood risk to people and property. In addition to shading the river, trees’ roots hold onto soils and slow bank erosion, provide habitat for birds and small mammals, and create green landscapes that improve the aesthetics, and even health, of urban residents and workers.

Moving Forward

We need to remind our decision-makers that implementing riparian vegetation and levee design solutions that support the ecological integrity of the Green-Duwamish River must be a priority. Investments in functional riparian buffers and multi-benefit levee projects promote the health of our ecosystems and our communities. If you live in the Green River watershed, please take the time to contact your County Council representative, mayor, and city council members and tell them that flood control plans need to do more for the Green River.

Healthy rivers are the lifeblood of the Pacific Northwest, vital to our identity, economy and way of life. Right now, we have an unprecedented opportunity to restore river health and wild salmon runs in the largest river basin in the region – the Columbia-Snake.

The three federal agencies that manage the Federal Columbia River Power System – the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Bonneville Power Administration, and U.S. Bureau of Reclamation – currently are holding open houses across the Northwest to gather public comments about salmon recovery in the Columbia and Snake rivers.

Dams have transformed the Snake and Columbia rivers, once among the world’s largest producers of wild salmon and steelhead (ocean-going rainbow trout). More than 400 dams harness the basin’s rivers for hydropower, irrigation and flood control. These dams, combined with other factors, have pushed some wild salmon runs to the brink of extinction.

Last May, American Rivers and our partners won a major court victory where the federal judge required a new examination of the impacts of Columbia and Snake River dams on imperiled salmon.

American Rivers believes any salmon recovery solution must look at the entire Snake-Columbia hydrosystem, and should include removal of four low-value dams on the lower Snake River in eastern Washington. Improvements in the operations of some Columbia River dams are necessary.

Over the past two decades, billions of dollars have been invested in habitat improvements throughout the basin to recover salmon runs. While these investments are necessary and have shown some positive results, they are not sufficient to bring wild salmon runs back to healthy, sustainable levels.

It’s time for a regional conversation about how we can remove the four lower Snake River dams and replace their benefits with cost-effective alternatives.

What does this transition look like?

We need to examine how power from the dams could be replaced through a combination of energy efficiency gains, new renewables like wind, and perhaps changes in the operation of the region’s other dams. Let’s look at how grain currently transported on barges instead could be moved on upgraded railroads and highways. Irrigation is provided from only the lowermost of four lower Snake River reservoirs – above Ice Harbor Dam – so let’s look at how that irrigation water could be pumped from a free-flowing river.

It’s time to act to create the future our children deserve: a future where wild salmon are restored to healthy, harvestable numbers; where continued investment in renewable energy and conservation provides low-cost and stable sources of energy; where water supplies and transportation infrastructure serve farms and communities; and, where risk of flood damage is reduced.

Achieving this vision will require strong leadership from the White House, Northwest governors and the Northwest congressional delegation.

And, it will require the voices of people like you who care about healthy rivers and wild salmon.

As other dam removal and water management settlements around the country have demonstrated, it takes hard work to chart out a solution that all parties can endorse, but it is possible. Just look at the tremendous dam removal success stories on the Elwha River in Washington and the Penobscot River in Maine, to cite just a few recent examples where fish runs are being restored and local economies are being revitalized.

Together with our partners, American Rivers is committed to finding the best solutions for the people and salmon of the Columbia-Snake basin. We hope you will join us.

Find an open house near you. Speak up for rivers and salmon!

Spokane, Washington: Monday November 14, 4 p.m. to 7 p.m. The Historic Davenport Hotel, 10 South Post Street

Lewiston, Idaho: Wednesday, November 16, 4 p.m. to 7 p.m., Red Lion Hotel Lewiston, Seaport Room, 621 21st Street

Walla Walla, Washington: Thursday, November 17, 4 p.m. to 7 p.m. Courtyard Walla Walla, The Blues Room, 550 West Rose Street

Pasco, Washington: Monday, November 21st, 4 p.m. to 7 p.m. Holiday Inn Express & Suites Pasco-Tri Cities, 4525 Convention Place, Pasco, Washington 99301.

Boise, Idaho: Tuesday, November 29, 4 p.m. to 7 p.m., The Grove Hotel, 245 S. Capitol Blvd.

Seattle, Washington: Thursday, December 1, 4 p.m. to 7 p.m. Town Hall, Great Room, 1119 8th Ave.

The Dalles, Oregon: Tuesday, December 6, 4 p.m. to 7 p.m., The Columbia Gorge Discovery Center, River Gallery Room, 5000 Discovery Drive

Portland, Oregon: Wednesday, December 7, 4 p.m. to 7 p.m., Oregon Convention Center, 777 NE Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd.

Astoria, Oregon: Thursday, December 8, 4 p.m. to 7 p.m., The Loft at the Red Building, 20 Basin Street

A quarter million homes were damaged, 93 dams failed and 52 lives were lost. Will we learn from the historic October floods of 2015 and 2016?

For decades scientists have been warning us that a warmer climate will bring more frequent and more violent storms to the Southeast. While the models are complex the concept is simple. Warmer temperatures evaporate more water adding more moisture to the atmosphere. This leads to more precipitation and more large storms.

Flooded roads in Andrews, South Carolina in October 2015, thanks to Hurricane Juaquin. | North Carolina National Guard

That is exactly what happened in the Carolinas during back to back years with historic October storms. In 2015, South Carolina witnessed these predictions come true as the remnants of Hurricane Joaquin collided with a stalled weather system turning on a meteorological fire hose that dumped record setting rains across much of the state – two feet or more for some communities.

North and South Carolina are still recovering from the October 2016 winds and flooding from Hurricane Matthew. At least 10 North Carolina counties received eight or more inches of rain in 24 hours setting off catastrophic floods. The Waccamaw River in South Carolina crested at 17.89 feet exceeding the 2015 flood by one and a half feet, and breaking the all-time flood record that stood for 88 years.

The 2015 and 2016 floods combined damaged more than a quarter million homes, caused 93 dams to fail and, most tragically, resulted in the loss of 52 lives. The 2015 floods are South Carolina’s second most costly environmental disaster causing more than $12 billion of economic impacts. Once summary information is available, the 2016 floods will certainly rank among North Carolina’s top environmental disasters.

Flooding from Hurricane Matthew damages homes near Selma, North Carolina, October 12, 2016. | U.S. Army National Guard

Flooding is becoming more frequent and more severe.

The impacts of floods out rank all other natural hazards and predictions indicate that the size of nation’s floodplains will grow by 40 to 45% by the end of the century putting even more communities in harm’s way. We must adapt to changing conditions to ensure the safety of our citizens, their homes and our roadways from increasing storms and floods.

The political leaders of the Carolinas have largely ignored decades of warnings from scientists relying instead on a business-as-usual approach to floodplain development, poorly planned growth and dam safety. North Carolina actually outlawed the use of climate science for evaluating future sea level rise.

Will the lives lost, property damaged and dams failed be enough to convince the states’ leaders that we cannot continue business as usual?

Here are commonsense solutions to adapt to increasing floods that both states should put in place to save lives and protect property.

- Protect and restore floodplains: Naturally functioning floodplains store floodwaters and reduce downstream flooding. We need to take advantage of these natural defenses.

- Get people out of harm’s way: Poorly planned growth has allowed development in flood prone areas, putting people in harm’s way. We need to replace developed areas with green spaces that can absorb floodwaters and buffer communities from damages. Charlotte, Milwaukee and Davenport, Iowa have been leaders in taking 21st century approaches for water and flood management.

- Strengthen state dam safety laws and programs: Ninety-three failed dams make it clear that our current standards, especially for earthen dams which are by far the most likely to fail, do not provide safety with the reality of today’s extreme flooding.

- Remove dams that do not meet safety requirements: We cannot wait until dams fail to take action. Poorly maintained and improperly designed dams need to be removed to protect downstream communities and infrastructure before they fail.

The leaders of North and South Carolina must learn from the disastrous floods of 2015 and 2016, and enact 21st century solutions that protect families from future floods. We must adapt to changing conditions and cannot continue business as usual while lives are lost and communities are devastated.

Tuesday is Election Day. I encourage each of you to exercise your most important right as an American citizen: the right to vote.

It doesn’t matter whether you live in a blue state or a red state, or whether you’re a Democrat, Republican, Green or Independent. We all need clean water to drink. And we all want healthy rivers where we can swim, fish and paddle with our friends and family.

Water crises like Flint, Michigan, show that we need to make sure our elected officials don’t take our water for granted. No one should have to worry about whether the water that comes out of their tap is safe for their children to drink.

This election, take time to better understand where your local, state and federal candidates stand on protecting rivers and clean water. And then get out there and vote!

On the river, things don’t always go according to plan. Whether it’s a paddling trip, a walk along the river’s banks, or a cleanup, unexpected obstacles can always appear even with plenty of foresight. Large cleanup groups – especially large cleanup groups using boats – encounter challenges and changes to plans frequently. As cliché as it might sound, it’s not about having a flawless cleanup or paddling trip, but how you deal with the challenges and making the most of your day that can make it really rewarding and fun for everyone involved. The key is flexibility.

Keurig Green Mountain, Inc. employees participated in a week-long cleanup of the Winooski River with American Rivers for the 11th year!

Lowell George

This past summer, 473 employee volunteers from Keurig Green Mountain, Inc. took to around 35 miles of rivers and parks in their communities to haul 53,930 pounds of trash from six sites across the United States. While these cleanup events did go pretty flawlessly (thanks to our local partners and the volunteers!) we did get some practice in adapting to our circumstances and being flexible with our expectations.

While completing a weeklong cleanup on the Winooski River in Vermont, volunteers pulled out 345 tires (no, really, 345!) in addition to the giant pieces of scrap metal, car parts, and general trash we found. In theory, volunteers would have accomplished this while paddling with the current down the Winooski and getting out occasionally to pick up trash. But because of an extremely dry summer, water levels on the Winooski were low. The good news: more of the riverbanks were exposed and as a result, we could see and collect much more trash than in other years; the bad news (and pro tip): it’s hard to paddle when there’s no water.

Keurig Green Mountain, Inc. employees participated in a week-long cleanup of the Winooski River with American Rivers for the 11th year!

Lowell George

Volunteers were not deterred and hopped out every couple hundred yards or so to walk their canoes – full of trash and sometimes up to 25 tires – down the river. As you can imagine, this didn’t always go smoothly. Only one canoe tipped over and, luckily, we were able to pull all the trash back out of the river and find a home for it in a secure boat. One particularly ambitious pair of volunteers packed their boat past the brim with tires to the point that it became too unstable to paddle and had to be tied to another canoe. The result: the Canoe-maran (Note: I don’t recommend trying this). While the contraption got a few concerned looks and even more laughs, it got the tires out of the river and kept everyone safe.

On one of our last shifts on the Winooski, the group was so prolific that within one-quarter of a mile of our launch site, all of the boats were full. A giant tractor tire, a baby swing set, a traffic cone, wooden poles, even more tires, and some odds and ends were pulled, against a swift current, back to our launch site. While our volunteers were disappointed they couldn’t collect more trash further down the river, they quickly adopted the revised plan and worked together to get their heavy boats through the deeper, faster moving sections of river.

Keurig Green Mountain, Inc. employees teamed up with Clean River Project to clean up the Merrimack River in Lawrence, MA.

Lowell George

Later that month, in Lawrence, Massachusetts, Keurig Green Mountain, Inc. employees took to the Merrimack River for a two-day cleanup. Using canoes as floating dumpsters, some volunteers walked through knee-deep water collecting debris while others on land piled trash high on their wheelbarrows. Both sets of people then emptied their hauls into a dumpster that was raised by a crane located at the park above. This method was so efficient that by the end of the second day, there was no trash to be found down by the river! Instead of lounging around on Friday afternoon, volunteers braved the heat and walked through the park, finding trash in every hidden path to the river, underneath every shrub alongside the bike path, and behind every tree backing up to an afterschool day care center. When the shift ended, the volunteers had to be convinced to stop and drop off their finds at the dumpster.

While everything might not have always gone to plan, by keeping an open-mind and adapting to the situations out of our control, the cleanups in Vermont and Massachusetts accomplished their goals: the rivers were clean and the volunteers were dirty.

[metaslider id=34288]

A flood is a natural occurrence. But did you know that one acre of healthy functioning floodplain wetlands can hold up to 330,000 gallons of water?

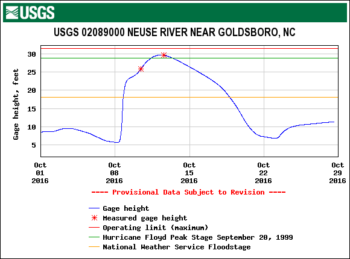

The flooding caused in North Carolina by Hurricane Matthew – a storm that was not supposed to hit the state – set a new mark for flooding in the eastern part of the state. This is even after all the work that was done following Hurricane Floyd in September of 1999.

The rains of Matthew came, they ended, and then days later the flooding really hit.

North Carolina has been dealing with hurricanes and their rain fall since settlers first arrived here.

These communities are accustom to the heart wrenching destruction that comes along with rivers surging from their channels and flowing down main street as if it were just a part of the river. These recent floods though were historic. They show that this was not localized nuisance flooding caused by a heavy rainfall but that it was a systemic flood that needs to systemic solution.

The 1997 book by John Barry, Rising Tide, received a national resurgence after the floods of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita that devastated southeastern Louisiana and New Orleans though its focus was on the last great flood of the area – the Mississippi River flood of 1927. This great flood produced a mentality within the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers that in order to keep people and the economy protected we had to control and contain our nation’s rivers. This lead to the construction of huge levees along the Mississippi River and started the now never ending struggle that the Corps has to keep that massive river in its designated place.

Unfortunately, that struggle has not always been able to produce the best outcomes.

The floods of 1993 were catastrophic because rain in the headwaters of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers were unprecedented and funneled downstream creating an unnaturally overwhelming amount of water that no levee could have contained. After those events – and other floods since then – the Corps and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) have been working to implement a new approach where ever possible, protect people and the economy by giving rivers space and keeping people out of the floodplain.

A river system is dynamic it goes through cycles of high and low flows (flood and drought). The ecology of the system is designed to be sustained through all phases of those cycles. Restoring floodplains to give rivers more room to accommodate large floods is the best way to keep communities safe. Giving rivers more room provides a number of other benefits including clean water, open space for agriculture, recreation and trails, and habitat for fish and wildlife.

When we manage rivers wisely, we can keep communities safe and enjoy all of the benefits healthy rivers provide. Small floods are very important to the health of a river and the land around it. They nurture life in and around rivers. The fish, wildlife, and plants that live in or along a river or floodplain, often need floods to survive and reproduce.

During big floods, healthy floodplains benefit communities by slowing and spreading dangerous flood waters that would otherwise flood riverside communities, harming people and property. Healthy floodplains are nature’s flood protection. Giving rivers room to move is our best protection against floods and is a great way to help keep rivers healthy.

North Carolina has the opportunity to avoid the mistakes of the Mississippi River basin and develop a systemic approach to flood management that protects people, reduces economic loss, and makes a healthier environment. We have examples from around the state that illustrate this type of work. Greenville, NC learned from Hurricane Floyd developed a plan to get as many people and businesses out of harm’s way. In Charlotte, the restoration of Little Sugar Creek highlights the importance of giving even smaller streams the space they need to flood by getting out of flood plain. Following the lead of those communities, the state and federal government needs to identify areas of the rivers that can be restored to give these rivers the space to flood and relieve pressure on areas where people live keeping them out of harm’s way.

This guest post by Christie True, Director of the King County Department of Natural Resources and Parks, is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Green-Duwamish River.

An important water quality assessment and monitoring study is under way to ensure that future projects to control water pollution on the Green-Duwamish River in King County, Washington, are well planned and timed to improve water quality. We will share those study results when they are complete next year, but we have a few key findings to report now.

The study makes clear that major investments over the last 40 years in treating wastewater and controlling combined sewer overflows (CSOs) are effectively improving water quality in a number of ways. For example, this work is keeping bacteria and nutrients out of waterways and helping to prevent problems, such as low levels of dissolved oxygen, that harm creatures like zooplankton and fish and that can even “kill” a water body.

The bad news is that the pollution found in stormwater runoff – metals, chemicals and PCBs – continue to seriously threaten our waterways. We are not investing as much in stormwater pollution prevention as we are investing in wastewater treatment and CSO control. That needs to change if we are going to save treasured waterways that are already under siege. The Green-Duwamish River in King County is one of those waterways. Last spring, American Rivers designated the Green-Duwamish River as one of America’s Most Endangered Rivers®.

The 93-mile Green-Duwamish River runs from the Cascade Mountains, through forests, agriculture lands, paved residential, commercial and warehouse districts, and one of the most industrialized centers in the state. For more than a century, humans have altered the river by manipulating the channel, removing streamside vegetation that cools the river, building a fish-blocking dam, and contaminating the river with industrial and stormwater pollution.

The hits are still coming – from rapid population growth, accompanying development, and from the effects of climate change.

The American Rivers’ designation shines a national spotlight on many of the problems that King County worked on for decades in order to restore and protect the Green River. Those issues compelled King County to team with the City of Seattle in 2014 to launch the Green-Duwamish Watershed Strategy to improve water quality and river ecology, and improve conditions for the entire 500-square-mile watershed.

A major focus area right now is a watershed-wide stormwater management plan to remove historic pollution, and prevent ongoing pollution with better stormwater maintenance practices. Along with reducing pollution, we are focusing on restoration of natural river flow and functions: acquiring river corridor parcels to set levees back and “re-greening” shoreline habitat.

We are making progress through:

- Partnerships that help recover salmon habitat (WRIA 9) and increase public awareness about stormwater (Puget Sound Starts Here).

- Community grant programs like Waterworks that provide funding for community projects benefitting water quality and controlling pollution at the source.

- Using Conservation Futures funds to acquire properties for salmon habitat and flood protection.

- Offering support for installing rain gardens and cisterns (RainWise) that help control stormwater runoff and preventing CSOs.

Despite all the work that is underway, it is clear that King County – along with other local governments, businesses and community members – need to invest more to save the Green River and other local waters, and we need to do it now.

One way is by adjusting our Surface Water Management fee – which is assessed on properties to address impervious surface areas. Increasing the fee will help us more effectively manage critical infrastructure to control stormwater and minimize the impacts of development on water quality. Proactive investments save money by addressing problems today rather than reacting to problems in the future, such as the sudden failure of aging infrastructure.

Historically, commerce and industry contributed the most to stormwater pollution. Today, it is the fluids that drip from our cars, the pesticides we spray on our gardens, and runoff from our roofs and driveways that are causing big problems for our waters. We all must boost our investment – with our dollars and our behaviors – to keeping all contaminants out of our water bodies.

Christie True is the Director of the King County Department of Natural Resources and Parks in Washington. The King County Department of Natural Resources and Parks works in support of sustainable and livable communities and a clean and healthy natural environment.

Christie True is the Director of the King County Department of Natural Resources and Parks in Washington. The King County Department of Natural Resources and Parks works in support of sustainable and livable communities and a clean and healthy natural environment.

When did standing in line at the mall on the day after Thanksgiving become a holiday tradition?

We love that REI challenged that idea last year with its #OptOutside campaign, and they’re doing it again this year.

We’re joining REI in encouraging everyone to #OptOutside on Friday, November 25. Instead of going shopping, head for your local stream or river! Go for a walk along a creekside trail, go paddling or fishing, explore a riverfront park. Because there’s no question that spending time near free-flowing water is much more enjoyable than being stuck in a crowd at the mall.

REI makes it easy to find nearby parks and other cool spots – just type in your zip code – and you can search by “kid friendly,” “dog friendly,” and by a variety of activities.

So start planning your outing! And share your river adventures with us. After you #OptOutside on Black Friday, tell us about your river story here.

At Halloween you might think more about crypts than cryptic, but here are three cryptic creatures that benefited by the removal of an eerie, outdated dam:

MUSSELS

Freshwater mussels often look like rocks when peering through the surface of a stream and have unfairly been called “rocks that suck” since they play an important filter-feeding role. The Cane River is home to a federally endangered freshwater mussel called the Appalachian elktoe. The removal of the Cane River dam will allow for an expansion of high quality habitat for these filter-feeding aquatic organisms.

HELLBENDERS

Often misaligned as snot otters, devil dogs, and mud puppies, hellbenders are a fascinating near-endangered salamander that hides in Southern Appalachian streams. In fact, they are the largest aquatic salamander in the U.S. and can breathe through their skin. The Cane River dam removal included features in the design to create shelter rocks for hellbenders to hide. Male hellbenders will defend their shelter rocks before the breeding season, so females have a place to lay eggs.

TROUT ANGLERS

A cryptic bunch, anglers keep a low profile while in pursuit of easily spooked wild trout. The Cane River dam created a dangerous hazard for river recreationists on the Cane River, a popular destination trout fishing stream. The removal of the dam will improve habitat for trout and make fishing safer for those chasing their favorite quarry.

Want to know more about the Cane River dam removal project?

The Cane River Dam located near Burnsville, North Carolina, was a 45-foot tall, 245-foot long concrete dam built for hydropower in the early 1900s. This dam was completely removed in October 2016 thanks to the enduring leadership of the Blue Ridge Resource Conservation & Development Council and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

American Rivers is proud to have supported this successful dam removal through technical assistance.

Other partners critical to the success of the project include the N.C. Clean Water Management Trust Fund, N.C. Division of Water Resources, N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission, N.C. Department of Agriculture and Consumer Sciences, North Carolina State University’s Stream Restoration Program, Appalachian State University, N.C. Department of Transportation, the Yancey County Soil and Water Conservation District, the Southeast Aquatic Resources Partnership, Wildland Engineering, and Baker Grading and Landscaping.