This week, Obama Administration took decisive action in adopting a 20-year ban on new mining for over 100,000 acres of public lands in the Wild and Scenic Illinois, Rogue, and Smith River watersheds and in portions of Pistol River and Hunter Creek in Southwest Oregon.

The protected area is a part of a vast, wild, largely roadless and globally unique environment bordered by the Pacific Ocean and wilderness area that is home to one the highest concentrations of Wild and Scenic Rivers outside Alaska. These rivers have some of the strongest runs of salmon in the lower-48, provide clean drinking water to downstream communities and support outstanding boating, hunting and fishing.

The action by the U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management follows years of robust public involvement, including overflowing local public meetings where over 750 people showed up to support the mining ban and comment periods that generated over 50,000 comments in support of protections for these wild rivers.

Thank you to our coalition of local, state and national advocates who have worked tirelessly to protect this area and especially the Klamath Siskiyou Wildlands Center, Kalmiopsis Audubon, Native Fish Society, Friends of the Kalmiopsis, and the Smith River Alliance.

An extra special thank you goes out to Senators Ron Wyden (D-OR) and Jeff Merkley (D-OR) and Representatives Peter DeFazio (D-OR) and Jared Huffman’s (D-CA) who have been incredibly dedicated in their years of work (in the case of Wyden and DeFazio two decades) to protect these special watersheds from industrial strip mining. Their bill, the Southwest Oregon watershed and Salmon Protection Act, was the original impetus for the agencies action today. Needless without the endless pressure endlessly applied by these champions of wild rivers this would not have happened.

And thanks to all of you, who sent in letters, called and contacted Congress on social media. It’s through your support that we were able to get this accomplished.

Unfortunately the ink isn’t even dry yet and the American Energy and Mining Association has already called on Congress, including a U.S. House that has already taken action to speed the sale of our public lands, to reverse these protections from mining despite the strong support from local communities and Oregonians of every political stripe.

We will have to remain vigilant to protect these unique, wild rivers, but today we should celebrate!

On Tuesday morning, the California Department of Water Resources (DWR) opened the Sacramento Weir to make more room for the Sacramento River to safely accommodate flood flows from the recent rains. This is the first time DWR has opened the weir since the flood waters of early 2005.

American Rivers and our partners have been working with DWR and the Central Valley Flood Protection Board (CVFPB) on a new plan to give the rivers of California’s Central Valley more room so that they can safely accommodate large floods while also providing a variety of other benefits for people and wildlife including clean water, open space, recreation, trails, water supply resiliency, and habitat.

View of likely location of new upstream weir to help flood flows from the San Joaquin River flow into the expanded bypass, thereby relieving stress on downstream structures and communities while also providing improved floodplain function and more habitat area. | Daniel Nylen

DWR and the CVFPB released the Draft Central Valley Flood Protection Plan (CVFPP) 2017 Update last week. The Draft Plan includes two exciting, new multi-benefit flood management projects that will give the rivers more room to reduce flood risk for people and, if designed correctly, provide a number of other benefits including improved habitat for endangered salmon.

The plan proposes to expand the Yolo Bypass on the lower Sacramento River and create a new flood bypass on the lower San Joaquin River. American Rivers has been involved in planning and advancing both projects over the last decade and will be reviewing and commenting on the 2017 plan over the next six weeks. Over the last six months, American Rivers has obtained $4 million in state grants from California Proposition 1 to purchase flood easements necessary for the new flood bypass on the lower San Joaquin River.

The Draft 2017 CVFPP Update is the culmination of over two decades of flood management reform in the wake of the 1997 flood discussed in my previous blogs, the Jones Tract failure of 2004, and Hurricane Katrina in 2005. All of these floods were a wake-up call, but it took the tragedy of Katrina to prompt the California voters to pass a bond measure in 2004 to upgrade our flood defenses and for the legislature to pass a series of reform bills in 2007. Sacramento and other Central Valley communities were and are at greater risk of catastrophic flooding than New Orleans. Thanks to the flood bond generously provided by the voters, we have made some good progress protecting vulnerable communities – particularly in Yuba and Sutter Counties, but implementing the reforms has been like moving a super tanker.

The idea of giving rivers enough room to safely convey floods is not a new idea. The first state flood plan prepared by William Hammond Hall in 1880 for the California legislature recognized the need to accommodate the monster floods that originate from atmospheric rivers colliding with the Sierra Nevada. Unlike the Mississippi River that originates near the Canadian Border and flows over 2,300 miles to the Gulf of Mexico, the rivers of the Central Valley originate at 10,000 to 14,000 feet and drop to sea level in a distance of only three to four hundred miles. The resulting volumes of water rightly humbled William Hammond Hall and other 19th Century flood planners.

Robert Kelley quotes text from Hall’s 1880 plan in his seminal history of flood management in the Central Valley – Battling the Inland Sea:

“Let it also be remembered that this plan applies…to the case where we deal with the ordinary floods of the valley, for no limit may be assigned to the amount of water which may at some time in the future come down this valley; and, as in the past there have been phenomenal inundations, now spoken of as “the flood of ’62,” “the flood of ’52,” etc., so may there yet be others as great or greater than they against the general spread of which no human foresight can provide, nor secure protection for the great body of the lands in the valley.”

Robert Kelly continued to explain Halls observations:

“Limited locations, Hall remarked, such as cities and towns could be raised in elevation or so well protected by high levees that they could probably be permanently protected. And yet, he observed wryly in one of his alarming asides, experience showed that there were two classes of levees: those that had been overtopped by floodwaters and those that were going to be. He continued: ‘And so it should be fully understood that floods will occasionally come which must be allowed to spread.’ But they must be allowed to do so not in their ordinary way, by opening out crevasses in the levees, but by putting strong weirs at several locations so that outflows could occur without causing damage. . .”

The legislature ignored this recommendation. Instead they followed the politically popular advice of other engineers who insisted it was possible to control the rivers with levees so that businessmen and farmers could develop the floodplains. It wasn’t until the devastating flood of 1907 that state leaders followed Hall’s advice and advanced the flood bypass plan developed by Hall’s two protégés – Manson and Grunsky – who by this time operated an engineering firm in San Francisco. With the assistance of the US Army Corps of Engineers (Corps), it took another 20 years to start to implement the plan on the ground.

The Sacramento Weir and the Sacramento Bypass were the first elements of the new plan constructed in 1926 and in the following decade several other weirs were constructed to release flood flows into the Butte Basin and the Sutter and Yolo bypasses. These other elements may have been constructed sooner if it wasn’t for the great flood of 1927 on the Mississippi River, which diverted the Army Corp’s attention away from California. The Corps appears to have taken lessons learned in the previous two decades of planning in California and applied them along the Mississippi in the aftermath of the 1927 flood. The design of the Bonnet Carre spillway, which was constructed in 1928, is almost identical to the Sacramento Weir. And the overflow basins designed to accommodate large floods – the Morganza and New Madrid floodways – are analogous to the Sutter and Yolo bypasses.

Unfortunately, in the second half of the twentieth century, Californian’s and their leaders forgot these lessons and redoubled their efforts to control the rivers of the Central Valley with dams and levees so that cities could grow onto the floodplains as fast as developers could build them. The floods of 1986 and 1997 exposed this folly, but it took Hurricane Katrina to catalyze true reform and another ten years of planning to return to Hall’s original idea – give the rivers enough room to safely convey the inevitable floods that nature will produce. Due to the larger floods that climate change has and will bring, it is now urgent to expand floodways on both the lower Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers to prevent catastrophic floods in metropolitan Sacramento and Stockton.

In the early part of the 21st Century, researchers from UC Davis and DWR discovered the value of inundated floodplains on the bypasses for California’s native fish and wildlife. Juvenile salmon that rear on floodplains grow three times as fast as juvenile fish that grow in the river channel, and bigger juvenile salmon are far more likely to survive their journey to the ocean and back.

Moreover, primary and secondary productivity from inundated floodplains provide foodweb resources critical to the support of the river ecosystem. Restored floodplains and wetlands also filter polluted waters, recharge depleted groundwater basins, and provide habitat for the millions of migratory birds that overwinter in California’s Central Valley. Giving rivers more room is not only essential to protecting people from flood waters, but it also helps keep rivers healthy for fish and wildlife.

Fortunately, the recent rains are coming to an end this upcoming weekend without another large storm and the potential for catastrophic flooding. This week’s precipitation has arrived mostly in the form of snow down to elevations of 4,500 feet rather than flood-inducing rain falling at high elevations. The reservoirs are now filling in an orderly manner and hopefully another storm will not occur before this week’s floodwaters recede. The lessons from the last century teach us that change takes time and political will. We will need both if we are to successfully implement the 2017 CVFPP Update in preparation for the future floods that climate change will bring.

On the first day of the new Congress the new Republican led U.S. House voted to ease the transfer of public lands signaling that the threat of our public lands being given or sold to state and private interests is real and imminent. This is a part of an outrageous broader scheme by some in Congress and state legislatures to transfer or sell our public lands and rivers and must be vehemently opposed by all Americans regardless of political party.

By adopting new rules to avoid costs to the federal treasury they came up with an accounting trick—decreeing that public lands have no value. Of course in so many ways this couldn’t be further from the truth. The real dollar of value public lands provide us is in fact immense. Our public lands and wild rivers provide billions of dollars annually in clean drinking water, outstanding recreation, and important fish and wildlife habitat.

The value of clean drinking water flowing off of our National Forest lands alone is estimated to be $7.2 billion annually according the U.S. Forest Service. These lands are the drinking water source for many rivers and aquifers that provide drinking water for 180 million Americans in 68,000 communities including Atlanta, Los Angeles, Portland, and Denver.

According to the Outdoor Alliance recreation contributes $646 billion to the economy annually supporting 6.1 million jobs. Close to 75 percent of the nation’s outdoor recreation takes place within one-half mile of streams or other water bodies and river-related recreation alone contributes over $97 billion annually to the U.S. economy. Once our public lands are transferred or sold we will likely lose access to many of these lands and rivers.

Aside from the economic arguments and perhaps more importantly: our public lands are simply a birthright and help define what it means to be an American. Our forefathers made sure these lands would not be owned or sold by a lucky few but held in trust for all Americans for all time. Let’s keep it that way.

Rivers on public lands across the country are at risk — including the Chattooga in Georgia, the Rogue in Oregon, the Au Sable in Michigan and the Gallatin in Montana. In the coming weeks and months we will be featuring some of the public lands, watersheds and Wild and Scenic Rivers across the country that are threatened by this extreme action by Congress.

What do you do with an outdated dam that blocks important stream habitat?

Find partners to work together to get rid of it!

The US Forest Service, along with numerous project partners, celebrated the completion of the Little Buck Creek dam removal and stream restoration project in September 2016. The project was located on Little Buck Creek in the Little Tennessee River basin in the Nantahala National Forest in Clay County, North Carolina.

The 30 ft high and 150 ft across outdated pond dam served no present day function and had become not only a public safety concern but also created a barrier to aquatic organisms like trout from accessing important habitat.

The pond dam was lowered and the concrete and steel structure that controlled the level of the pond was removed. The stream channel of Little Buck Creek upstream and downstream of the former pond was reconnected by performing over 200 feet of channel restoration. Large boulders and woody debris were used during the restoration to provide channel stability and to create habitat features.

Southern Appalachian brook trout now have access to new habitat thanks to this river restoration project. “As a part of the mission of Trout Unlimited our job is to expand habitat for trout and salmon. One of the best ways to achieve our mission is to partner with other organizations and agencies just like this dam removal project on Little Buck Creek in North Carolina,” said Keith Curley, Vice President of Eastern Conservation with Trout Unlimited.

The project was made possible through funding partnerships between Trout Unlimited, the US Forest Service, US Fish and Wildlife Service, and the Wildlife Conservation Society. The project was implemented by the US Forest Service and the NC Wildlife Resources Commission with support from Trout Unlimited and American Rivers. Backwater Environmental, Inc., a heavy equipment contractor, performed the environmental restoration.

“The goal of restoring aquatic organism passage in Little Buck Creek was achieved through the efforts of the federal, state and non-profit organization’s concerted partnership. This project was essential to providing uplift to the aquatic ecosystem which was made possible only through this unique partnership” said Scott Loftis with the NC Wildlife Resources Commission.

[metaslider id=35399]

As a massive, warm storm bears down upon California this weekend, it is worth taking note of how climate change is affecting our rivers and what our leaders are doing to protect the people and wildlife that depend upon them for their livelihood. As discussed in my previous blog, the forecast calls for an atmospheric river event with heavy rain at very high elevations on Saturday and Sunday. After a week of abundant snow at relatively low elevations, the National Weather Service is predicting heavy rains at elevations up to 10,000 feet in the Sierra Nevada.

There is a common misperception that these “rain on snow” events cause flooding due to extensive melting of the snow pack. In reality, relatively little snow melts because of the rain and in some cases the snow pack can actually absorb some of the rain. In most cases, the rain just flows through the snow pack and into the rivers without significant snowmelt. The primary mechanism through which rain on snow events create large floods is that a larger area of the watershed is subjected to rain rather than snow. The floods are large because the area contributing to run-off is larger.

The San Joaquin Watershed upstream of Fresno has a median elevation of 7,000 feet and rises to as high as 14,000 feet. Nearly all precipitation events occur in the winter and spring when it is still relatively cool, and as a result, precipitation falls as snow over large parts of the watershed. As the climate changes and individual storms become warmer, rain will fall over a larger part of the watershed. This weekend’s storm will drop rain at elevations up to 10,000 feet, increasing the total area contributing runoff over the next week by 20-30 percent compared to a storm with snow levels at 7,000 feet.

The Draft 2017 Update of the Central Valley Flood Protection Plan issued this week by the California Department of Water Resources predicts significantly larger flood flows for the San Joaquin River and its tributaries moving forward. The San Joaquin Basin Wide Feasibility Study, an appendix to the plan, predicts that a 200-year flood event with climate change could cause a flood roughly twice the volume of the 1997 flood (the largest flood on record), doubling the flood damages to urban cities and resulting in “massive loss of life.” Doubling such a flood is truly horrific.

If climate change is going to make the watershed larger, we need to make sure that the floodways are large enough to safely carry those flood waters. American Rivers believes that the best way to protect communities from these dangerous new floods is to give rivers more room to safely accommodate and convey the larger floods that a changing climate will bring. Giving rivers more room will also create new opportunities for open space, recreation, and trails along the rivers of the Central Valley. And giving rivers more room will provide better habitat for Chinook salmon and several other threatened species that rely on healthy rivers.

Stay tuned to learn more about how American Rivers and the new flood plan propose to give rivers more room, keep communities safe, and restore habitat for endangered species.

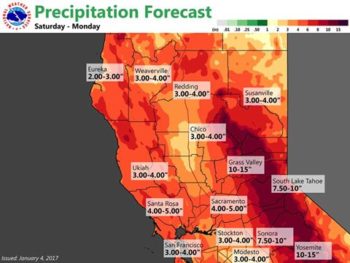

Extreme droughts often end in floods. Australia’s epic 10 year drought ended in catastrophic flooding in 2011. Texas endured 5 years of crippling drought until it ended with catastrophic flooding in May 2015. If the National Weather Service Forecast for rainfall between January 7th and 10th is correct (see map below), California’s drought may end in catastrophic flooding as well.

Current wet weather and official forecasts of a “plethora” of water coincides with the release of the new draft 2017 Central Valley Flood Protection Plan by the California Department of Water Resources (DWR). American Rivers and several of our partners have been working with DWR on the development of this new flood plan for nearly five years. Stay tuned in the next several days for more reports on how the flood plan is essential for protecting people and rivers against the vagaries of drought and a changing climate. But for now, let’s turn our attention back to the heavy rainfall predicted by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Current wet weather and official forecasts of a “plethora” of water coincides with the release of the new draft 2017 Central Valley Flood Protection Plan by the California Department of Water Resources (DWR). American Rivers and several of our partners have been working with DWR on the development of this new flood plan for nearly five years. Stay tuned in the next several days for more reports on how the flood plan is essential for protecting people and rivers against the vagaries of drought and a changing climate. But for now, let’s turn our attention back to the heavy rainfall predicted by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

It’s never over until it’s over, but it’s not too soon to start dreaming about the end of California’s five-year drought. It will take years to recover depleted groundwater reserves, particularly in the San Joaquin Valley and Tulare Basin. The California State Water Resources Control Board also just announced the need for continued urban water conservation measures as Central and Southern California remain in drought conditions. But the next few days may cause the reservoirs rimming the Central Valley to fill and ultimately spill. Here is what the national weather service posted on January 4th regarding the storm forecasted for this weekend:

“The next wave with atmospheric river moisture breaks down the transitory ridge quickly late Friday evening. An upper low sits out over the eastern pacific with west-southwest flow over region that is forecast to bring very significant rainfall to the area Saturday through Monday. Models have the integrated water transport centered over the northern and central Sierra, so a plethora of rainfall could fall over the Sierra, possibly 10 to 15 inches over the Sierra and 3 to 5 inches in the Valley.

With these numbers in the Sierra/foothills, models show return rainfall intervals of every 5 to 10 years northward of I-80 and 10 to 25 year returns southward. This additional rain on top of already saturated soil will likely cause some river, stream, creek and street flooding. Non-regulated rivers (non-dammed) like the Cosumnes River, the American River above Folsom Dam,and other Sierra rivers south of I-80 have not seen potential flooding of this nature since December 2005. This three day expected Sierra rainfall amounts are approximately twice the January monthly average.”

Yes, this does indeed sound like a “plethora” of water. Few people realize that California is subject to some of the most extreme precipitation events in North America due to phenomena known as “Atmospheric Rivers”. These vast plumes of water vapor, popularly known as a “Pineapple Express”, account for a substantial fraction of California’s water supply, and extreme atmospheric river events can cause catastrophic property damage and tragic loss of life. The great flood of 1862, which was thought to be an atmospheric river, destroyed one quarter of all taxable property in California, bankrupted the state, and transformed the Central Valley into an “Inland Sea”. Stay tuned to see how this weekend’s forecasted storm will match up against the flood of 1862.

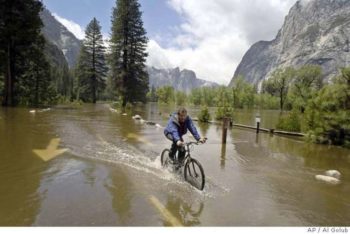

There is some evidence that the forecasted rains will potentially match the 1997 flood – the largest recorded flood in California not counting the 1862 event which occurred before good records were kept. The NOAA forecast calls for flood stages on the Merced River in Yosemite Valley to reach 23.1 feet, only three inches below the record 1997 floods that obliterated two popular campgrounds and other infrastructure in the valley. The San Francisco Chronicle has some riveting footage on what that flood looked like up close and personal.

Chris Stewart bicycles down a flooded Chapel Straight in Yosemite National Park, Calif., Monday, May 16, 2005. | AP Photo/Al Golub

The 1997 atmospheric river storm resulted in major floods throughout the Central Valley that rewrote the hydrologic record book. Below Friant Dam near Fresno, the river peaked at 60,000 bic feet per second (cfs), four times the projected “100-year flood.” The 1997 floods came after two very wet years. This weekend’s storm, however, follows several years of drought and most of the major reservoirs rimming the valley are at or near historic averages with significant capacity still remaining to capture projected floods. It will probably take more than one atmospheric storm to fill and spill the depleted reservoirs, but it may very well fill the reservoirs and a second storm of this magnitude in the next few weeks could cause widespread flooding throughout the Central Valley. This morning, the last line of the extended NOAA forecast for the Sierra read as follows:

“Longer-range models deviate a bit from next Wednesday onward, but the ECMWF and GEM are both currently hinting at yet another atmospheric river impacting Northern California late next week.”

Stay tuned!

Like many other Coloradans, each January 1st, I like to set resolutions to restart in the New Year. Probably like you, my resolutions are usually focused on self-improvement – like eating healthier or making time for the gym – other times its adding simple acts of kindness to my daily routine. The holidays have a way of reminding us to do and be better, not just for ourselves or those close to us, but also for each other and the planet we depend on.

Clearly, water plays a critical role in our lives. Not only do we all need clean drinking water, but it also fuels agriculture, manufacturing, and recreation that support our way of life. Like many of you, I love my local rivers and streams and look forward to every chance I get to enjoy them.

Here in the Colorado River Basin, rivers and streams are the lifeblood of our livelihood and economy, with Colorado River and its tributaries contributing to a $26 billion economy. This past November, we celebrated the first anniversary of the signing of the Colorado Water Plan, a first of its kind plan to protect and conserve water in Colorado. While this milestone is something to celebrate, implementation thus far has been slower than anticipated. But new opportunities lie ahead in 2017 as the Colorado Water Conservation Board (CWCB) pledged to secure $55 million in funds for implementation. These funds include money dedicated towards creating stream management plans on rivers statewide, which will develop methods to manage rivers and streams in Colorado – keeping them healthy for both nature and people.

Implementing larger conservation initiatives like the Colorado Water Plan are critical for not only the rivers of Colorado, but for the entire Colorado River Basin. However, large initiatives aren’t the only thing that will make a difference in conserving our rivers. As an individual, it may be challenging to determine how you can make a difference in your water use. There are a number of “resolutions” you can add to your list that will not only conserve water and protect local rivers, but reduce your impact on the local environment as well.

This year, I’m determined to do a better job of conserving water in my house and reducing my impact on our rivers. In addition to my usual resolutions, I’m adding a few to protect the rivers I love and depend on – join me! Here are a few of the resolutions I’m adding to my list this year:

Watering the garden and landscape early in the morning.

Here in Colorado, the sun is hot! I recently moved into a new house and this summer I’m planning to plant native species that require less water and can survive sunny conditions. In order to reduce evaporation and help water reach their roots, I will water my plants and vegetables early in the cool mornings to reduce waste. Another added benefit – watering early in the day can help reduce unwanted garden pests like slugs!

Eating local and shop at your local farmers market.

Sustainable farms and ranches help protect open space and clean water supply. This year, I’m going to make an effort to eat more locally and visit my neighborhood farmers market. In Colorado, many local farmers and ranchers have worked with local land trusts and open space programs to protect water rights and important riverside lands, keeping more water in the river. Eating locally also helps reduce energy used for transporting those goods to market, which in turn, reduces the amount of water needed to create fuel. Shopping at the farmers market is fun too – especially when I bring my friends and family to enjoy it with me!

Committing to shorter showers and checking for leaky pipes and faucets.

I will cut down on my shower time by washing my hair every other day to reduce time, and remind my husband to turn off the water while he shaves. A four-minute shower uses approximately 20 to 40 gallons of water (depending on your shower head). Not to mention, a small drip from an old, leaky faucet can waste up to 20 gallons of water per day. In addition to conserving water, you could see some significant water savings right away on your monthly bill.Using my dish and clothes washer only when they are full.

While it can be more convenient to run your washer when you need it, I will only run my dish and clothes washers when they are full. Not only is this more energy efficient, but running a full dishwasher instead of handwashing dishes can save more than 10 gallons per load. And before I do a load of laundry, I’ll be sure to check its size before pressing start to make sure the dial is adjusted to match the amount of clothes in the machine. And, I think about whether I could wash this load in a cooler temperature – hot water accounts for a dramatic increase in my energy bill, and turning the dial down from hot saves energy. Every drop counts!

Calling my state and federal representatives and advocate for water conservation.

We can make a difference. By calling my representative I am letting them know that the water and rivers in Colorado are important to me and I want to see them protected. Stay up to date on water conservation initiatives by signing up for local e-Newsletter where information is included about water conservation. Check out Denver Water’s Conservation Newsletter or the Denver Botanic Gardens newsletter to learn more. Additionally, take time to learn more about important initiatives like the Colorado Water Plan and what it means for local rivers. This innovative plan is critical for the protection of rivers in Colorado. In order to see our rivers protected, we need to continue implementation of the conservation strategies set forth in the plan. First and foremost, I plan to call my representatives and let them know that I want them to approve the budget for the Colorado Water Plan set forth by the Colorado Water Conservation Board. Join me and let your representatives know that the Colorado River is important to you and you want it protected.

These are a few things I’m committed to doing in 2017 – leave a comment below about what resolutions you are making to protect the Colorado River!

Strap on your PFD, there’s rough water ahead.

No matter who you supported in the recent election, the result requires facing some hard truths. Based on positions taken during the campaign, it’s clear that a Hillary Clinton victory would have meant a largely seamless continuation of President Obama’s environmental policies; energetically taking on climate change, redoubled efforts to protect clean water and clean air, and careful stewardship of natural resources and public lands. The election of Donald Trump will move things in a radically different direction.

While President-elect Trump has said he wants to uphold the conservation legacy of Theodore Roosevelt, he has also stated on more than one occasion that climate change is a “hoax.” He has promised to pull the plug on the Obama administration’s Clean Power Plan and the Clean Water Rule that restored federal protection of small streams and wetlands across the country. And he plans to dramatically increase oil and gas, mining, and timber exploitation of federal lands.

So far, his choices to head federal environmental and natural resource agencies show a determination to move this agenda forward, and then some. His choice to head the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Oklahoma Attorney General Scott Pruitt, is a climate change denier who has made his living suing to prevent the EPA from making strong moves to protect air and water. President-elect Trump’s pick for Interior Secretary, Congressman Ryan Zinke of Montana, has a mixed conservation record, but has opposed the Clean Water Rule and supports increased energy development on federal lands. Meanwhile, a new Congress also will arrive in January, emboldened by the Trump administration to attempt rollbacks of our most important and effective environmental laws.

Mount a strong defense

This isn’t the first administration or the first Congress hostile to environmental protection. I cut my teeth as a conservationist during the first Bush Administration, successfully defending the Clean Water Act and the Endangered Species Act from legislative attack. Those two keystone environmental laws remain the basis for much of the work we do to protect rivers and clean water.

Just this year, American Rivers thwarted an effort by the hydropower industry to roll back protection for rivers from the damaging effects of dam construction and operation. We face a monumental challenge from a Congress dominated by opponents of environmental protection and backed by a seemingly anti-environmental administration. But we know how to play defense and, staffed with some of the best environmental advocates, we’re good at it.

Redouble our efforts in the field

We are also really good at getting things done in the field, and we will build on that success as Washington becomes a potentially more difficult place to get results. American Rivers’ River Restoration Program is the nation’s undisputed leader in dam removal, spearheading the removal of over 200 dams and providing guidance and technical support to hundreds of others.

Our Clean Water Supply team is promoting better management of water resources in river basins and metropolitan areas from Tucson to Atlanta, bringing together stakeholders across the political spectrum. Our field work to conserve rivers and wetlands has resulted in restored wetlands in California, pristine rivers protected from oil and gas drilling in Montana, and new recreation and tourism opportunities in South Carolina.

With greater challenges ahead at the federal level, we’ll continue to build on our work with state and local governments, where we’ve had great success influencing law and policy at the grassroots.

Speak out for rivers and clean water

American Rivers is the leading voice for rivers and clean water in the United States and that role is more important than ever. We will use every opportunity to educate policy-makers, opinion leaders, and the public about the importance of rivers and clean water. In traditional and social media, at conferences and meetings across the country, we will be a clear voice for greater conservation efforts and aggressively call out attempts to roll back protection for rivers and streams. We will defend the roles of sound science and public participation in environmental policy-making, working to ensure that our nation’s lands and waters are managed sustainably and equitably for all Americans.

Capitalize on opportunities

Despite the changes in the White House and Congress, there will be opportunities in the coming years to promote proactive river conservation at the federal level. Rivers and clean water should be bipartisan issues, and in fact some major river conservation success stories have unfolded in what seemed at the time to be unlikely political circumstances. The highly successful effort to restore New England’s Penobscot River began with an investment of federal funds by the George W. Bush administration; a Republican Congress in 2006 passed into law the program that provided funding for many of American Rivers’ dam removal projects over the last 10 years; and legislation that protects the headwaters of the Snake River as Wild and Scenic is named after the late conservative Republican Senator Craig Thomas of Wyoming.

It’s not immediately clear when those opportunities will arise, so we will need to be ready. That’s where American Rivers’ River Conservation Agenda for the New Administration comes in, six policy proposals that should have bipartisan appeal as they address pressing water supply and quality issues, support economic growth, promote efficiency and cost savings in government natural resource management programs, and protect and restore rivers and streams across the country:

- Celebrate the 50th Anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act with a bold initiative to strengthen and expand the Wild and Scenic Rivers System.

- Establish a Clean Water Trust Fund to finance improvements to natural and man-made infrastructure to ensure that clean water is readily available to all Americans.

- Adopt integrated water resources management as the organizing principle for federal water management.

- Launch an “Open Rivers Initiative” to coordinate and prioritize dam removal across the country.

- Improve protection and management of the nation’s floodplains.

- Prioritize and focus Farm Bill programs and other agriculture funding to solve water and river conservation challenges.

Click here for a detailed description of each.

Together, We Can Do This

As we move into a new year and a new political era, we need to be clear-eyed about the challenges we face, but we can’t let those challenges discourage us or deter us from our course. In fact, there is still a lot we can accomplish for river conservation.

As any good river guide will tell you, when the water is at its roughest is not the time to hunker down. Rather, it’s time to put on your helmet, find your point-positive, and paddle like hell.

Even though the snow has just started to fall and winter is here, I can’t help but think about summer. When I think about getting outside, especially on the river, one of the first things I look forward to do is jumping in! The cool water provides such a welcome relief from the hot sun beating down on my neck and back. But just jumping in can also be hazardous, which is where the Snake River Waterkeeper is working to educate river lovers – from swimmers and boaters to walkers and anglers – about the safety of local rivers and streams within the Snake River Basin.

Snake River Waterkeeper, a 2016 Connecting Communities to Rivers Grantee, has made connecting with and recreating on the Snake River easier and safer for everyone with their Swim Guide App, which can be downloaded for free from the Apple App Store or Android Google Store. The Swim Guide App provides valuable information about river health and safe recreation, ranging from eastern Washington and Oregon across Idaho and into western Wyoming. The free App focuses on areas that are heavily used by swimmers and other river recreation enthusiasts, featuring directions, an “I’m Here!” button to meet up with friends, and identifications of reaches where water is too polluted for swimming.

Water quality data and safety information is continuously updated as it becomes available. This past summer, with the help of nearly 100 volunteers, Snake River Waterkeeper cleaned up river trash and sampled water quality at 110 sites – spanning the full reach of the Snake and its tributaries – to ensure safe river outings for Swim Guide users. Data is under ongoing evaluation to determine water quality trends as well as to substantiate and guide programmatic objectives that are helping improve water, fisheries, and experiences in the Snake River and its myriad tributaries.

The Swim Guide and 2016 monitoring efforts have wrapped up for the year, but if you are interested in volunteering with Snake River Waterkeeper next summer – please let us know! Plans to get out and improve water quality on our rivers next year are already underway!

There’s a bittersweet feeling about the last fishing trip of the season.

On the one hand, there’s the sadness of knowing that I’ll have to wait till springtime to get back on the water. On the other hand, knowing that it’s the last trip lets me look back on some amazing times and look forward to trips next year that I haven’t even planned yet.

Since joining American Rivers, I’ve had the chance to fish on some spectacular streams, and this year’s trips have included several of those. What made these trips even better was being able to fish with some truly wonderful people I’ve met through the Anglers Fund. For starters, there was the Greybull River trip with Jay, one of the most interesting people I know; Paul, whose quiet appreciation of nature is something to learn from; and Greg, who helped us appreciate his home waters. In addition to chasing the Greybull’s beautiful cutthroats, we learned about efforts to bring back the once-thought-to-be-extinct black-footed ferrets, local history with Butch Cassidy, and how grizzlies are expanding their range. We even got a couple cutthroats to take a fly tied in our American Rivers’ logo colors, even though there is nothing in nature that looks like that fly. You’ve got to love cutthroats.

There was the trip to Fish Creek with Dick and Lora, two of the most genuinely nice people you will ever meet. In his mid-80s, Dick is as determined as any teenager to wade out to be within range of rising fish, and his thirst for learning new ways of mending line on the water is inspiring. If I am able to fish half as well as he does when I’m his age, I will have really accomplished something.

And then there was my last trip to the Davidson River with my son Luke and my cousin John a few weeks ago. There’s something special about fishing with family, perhaps because we know that the chances are pretty good that we will go again. The river was low even for this time of year, but the fall colors were brilliant – surrounding us with bright oranges, reds, and yellows. Some of the leaves were still on the trees, some were on the forest floor, and some were collecting in eddies and slower water. It was a perfect fall day, with winter clearly on its way.

As the weather gets colder, I’ll look back over these trips and others, appreciating the opportunities to fish these beautiful rivers with good friends and to learn more about what makes them special. And soon, as winter sets in, I’ll start pulling out maps and guide books, looking forward to the New Year’s fishing. (If you’d like to see the places we go on our Anglers Fund trips, please click here.)

I hope that you’ll enjoy both looking back over your time on the water this past year and looking forward to trips you’ll take next year.

Happy Holidays.

This article was written by Susan Culp, a contractor for American Rivers in the Verde Valley. This article originally appeared on Audubon Arizona’s online Blog. Read the original article here.

The Verde River is one of our last remaining perennial and free-flowing rivers. With a healthy riparian corridor along its length, it is well-known for its importance to a great diversity of resident and migratory birds and other wildlife. The species richness of the region has been recognized by two Important Bird Areas (IBA) already – the Lower Oak Creek IBA near Page Springs and the Tuzigoot IBA that runs along the Verde River through Clarkdale and Cottonwood. However, Camp Verde, with exceptional riparian habitat supporting countless species, remains an under-birded area.

The value of wildlife and the importance of protecting the river and riparian habitat on which it depends was one of the most resounding messages heard from residents during the Town of Camp Verde’s efforts to develop a comprehensive Verde River Recreation Master Plan. The Plan, adopted unanimously by the Town Council in February of 2016, showed wildlife viewing and appreciation as among the area’s most popular recreation activities. An IBA designation along the Verde River in Camp Verde would fit well with community values, add to the area’s bird and wildlife watching opportunities, and support low-impact but economically-valuable recreation and tourism. According to research conducted by Tucson Audubon Society in 2013, watchable wildlife recreation activities contributed over $40 million toward retail sales, $22 million in salary and wages, and supported almost 600 jobs in Yavapai County alone.

In September, Audubon Arizona and Tucson Audubon Society convened a workshop for local stakeholders about the IBA designation process. The event was attended by local conservation groups, public land managers, private landowners, and volunteer birders. The reception was positive and to date over 20 volunteer birders in the region have offered to assist by conducting field surveys to support the IBA application.

The surveys for the IBA application will begin in January 2017, and will be conducted seasonally to coincide with the arrival of spring migrants, summer nesting behavior, and fall migrations. The Camp Verde IBA effort is unique in Arizona – where a community has taken the initiative directly to pursue watchable wildlife opportunities; where residents have expressed keen interest in protecting important riparian wildlife habitat in their neighborhoods; and where local groups, landowners, land managers, and citizens have eagerly volunteered to support the project. American Rivers is working closely with Friends of Verde River Greenway and the Town of Camp Verde to craft the IBA application for submission to Audubon and BirdLife International. The project is also endorsed by the Northern Arizona Audubon Society.

This effort represents a tremendous opportunity for the Town of Camp Verde to support sustainable recreation and economic development while leaving a light footprint on the natural world and reflecting the community’s values.

If you are interested in participating in the survey process, please contact either Susan Culp at sculp@nextwestconsulting.com, who is organizing the IBA application on behalf of American Rivers. There are opportunities for all wildlife lovers to get involved with this exciting project – the more the merrier!

American Rivers supporters know a dam removal is never just about removing a dam.

It’s about restoring habitat within and alongside the river, so wildlife may thrive. It’s about reopening fish passage, creating access to long obstructed spawning, and rearing grounds. It’s about protecting the cultural, tribal, ecological, and recreational values of fisheries. It’s about the economic vitality of communities that rely on recreational tourism, swimming, floating and boating. And it’s about health and safety, removing dangerous obstacles that drown swimmers and boaters, while freeing flows to keep stream temperatures cool and reduce dangerous algal blooms.

There are so many benefits to taking down a dam and restoring a river, but none can be accomplished without community support, a solid plan, and funding. On November 29th, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation acknowledged this by announcing their Open River Fund, a 10-year, $50 million commitment to “restore river systems and protect priority landscapes in the Western United States.” This new initiative focuses on revitalizing watersheds by removing obsolete, unsafe and unnecessary dams – “deadbeat dams,” in the words of Michael Scott, the Hewlett Foundation’s acting director of environmental programming. The American Society of Civil Engineers reports that more than 4,000 of the nation’s 90,000 dams fit this bill. The Open Rivers Fund will kick off by contributing funds to three dam removal projects that have united communities: the Matilija Dam in Ventura, California, a series of dams and impoundments on the Rogue River system, and the Nelson Dam in Washington’s Yakima River basin.

Nelson Dam

American Rivers has been involved in the Nelson Dam removal discussion for several years, as part of the ongoing Yakima Basin Integrated Plan. Nelson Dam, on the Naches tributary of the Yakima River, was built in the 1920s to divert irrigation water for the City of Yakima and the Naches-Cowiche Irrigation Company. The original structure provided no fish passage and shunted water to its 8,000 users through a series of leaky wood stave pipes. Recent upgrades swapped the diversion to a more efficient system that utilizes just half the historical amount of water, abolishing the need for the eight-foot storage dam.

Yakima County natural resources staff proposed a design that removes the dam and regrades the riverbed, allowing the City of Yakima to divert its water while also permitting sediment transport and fish passage. If done correctly, Nelson could serve as a model for other irrigation diversion dams in the West that block fish and sediment.

Upstream of Nelson Dam, an intentional levee breach allows floodwaters to slow and spread into sidechannels. | Nicky Pasi

Nelson Dam is also dangerous and damaging. It creates a chokepoint across the Naches River where Highway 12 and a sheer volcanic wall bracket the natural floodplain. Over the past century the dam has held back countless tons of sediment, silt, and gravel, raising the bed of the river enough to ensure the Naches River overflows its banks and threatens the community during even modest floods.

Floodwaters close the highway to emergency services, cut off local residents, and limit access to the nearby Yakima Regional Medical Center. The County and community found themselves trapped in an expensive cycle of building levees, losing those levees to persistent flood impacts, then faced to constantly rebuild and expand those levees. Eventually the County realized that it was cheaper to buy out the most at-risk floodplain properties and allow the river room to maneuver.

Sediment also blocks the fish ladder that was added to the dam in 1985, rendering it useless for much of the year. What was once tremendously productive off-channel habitat for salmon and steelhead has been barely accessible for more than a century. Removing Nelson will restore sediment transport and fish passage, allow whitewater enthusiasts safe passage along the river, reduce the risk of floods, and create cost savings on infrastructure repairs.

Stakeholder Consensus

The Nelson Dam is an 8-foot-high diversion dam that sits just upstream of the city of Yakima on the Naches River in Washington. | Justin Clifton

Given its many benefits to multiple stakeholder groups, it’s no surprise that the Nelson Dam removal is a key project of the Yakima Basin Integrated Plan. This watershed-scale resource management plan was created by federal, state, and local government agencies, private water users, environmental partners like American Rivers, Trout Unlimited, and the Wilderness Society, and the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation. The Yakima Plan has been a tremendously successful collaborative process, and the relationships it created have increased odds of success for individual projects like Nelson Dam.

The Open Rivers Fund will contribute $75,000 toward the reconfigured roughened channel design and the consolidation of two downstream diversions into the existing pipeline. A portion of those funds have been awarded to American Rivers to provide community engagement, outreach and technical assistance.

American Rivers knows that dam removals are never just about the dam. We also know that rivers are our most valuable and vital pieces of infrastructure. Everything – our roads, our railways, our cities – were shaped by rivers, especially in the arid West where 70% of rivers have been dammed or impounded. Letting a river be a river, giving it the space and the freedom to do what a river does, is the best possible use of that infrastructure for all those who rely on its services. It can even cost much, much less than repair and upkeep on dams and levees! We are very pleased and grateful to partner with the Hewlett Foundation through the Open Rivers Fund to allow the Naches its breathing room.