On his way out the door, President Obama left a parting gift for the Mississippi River. Late Thursday evening, on January 19th, the White House issued a resolution to stop the damaging New Madrid Levee Project.

The New Madrid Levee was a proposed part of the St Johns Bayou New Madrid Floodway Project. Located in the bootheel of Missouri, the US Army Corps of Engineers (Corps) was proposing to build a 1,500-foot levee. At New Madrid, the levee would cut off access to the last remaining naturally functioning floodplain in the region. About 70,000 acres of floodplain would be lost and about 53,000 acres of wetlands would be drained. The purpose of the new levee? To facilitate development of the New Madrid Floodway.

The New Madrid Floodway is part of the Mississippi River and Tributaries Project. It is flooded periodically to protect levee systems around other Mississippi River communities. Unfortunately, every time the floodway has been operated, the state of Missouri has sued to stop its operation. The suits are brought to stop the row-crop dominated floodway from being flooded and cause delays in the floodway operation. In 2011, a lawsuit contributed to the delay that resulted in a levee breach at Olive Branch, IL and the destruction of 50 homes.

Building the levee and promoting more development in the floodway would have increased the pressure to avoid operation of the floodway during a major flood. This would lead to more lawsuits and delays, putting communities like Cairo, IL at risk.

Due to the massive environmental impacts of the project, the US Fish and Wildlife Service issued a referral to the Council of Environmental Quality, asking the President to step in and evaluate the project. The outcome was an 11-page letter of resolution signed by the Department of Interior (which oversees the US Fish and Wildlife Service), US Army Corps of Engineers, and the President’s Council on Environmental Quality.

In the resolution, the agencies agree that the only way to mitigate for the environmental impacts of the project would be to provide free and open access to another comparable section of floodplain nearby. The Corps acknowledged that, at this point, there are no other landholders willing to provide the 70,000+ acres of floodplain for the mitigation – an area that would fit Manhattan Island almost 5 times.

This basically sets up a hurdle that would be impossible for the Corps to jump over to proceed with the levee project.

Can President Trump just overturn the decision? He can try. But, the resolution builds on well-established science about the environmental impacts of the project. If the Trump administration tries to do an about face on the facts, they’ll have to explain it in court, and one judge has already ruled against the levee project to date.

While the fight might not be over yet, this is a major victory for the Mississippi River. Thank you, Mr. Obama.

2016 was a year of many accomplishments for National River Cleanup®. The program celebrated its 25th anniversary this past year with a number of new initiatives and new members to the American Rivers family.

With the help of our supporters, we:

- Registered 1,953 cleanup sites;

- Mobilized 47,648 volunteers;

- Removed 3.4 million pounds of trash;

- Cleaned over 7,899 river miles;

- Motivated over 1,200 individuals to take our National River Cleanup® Pledge to pick up 25 pieces of trash in 25 days;

- Kept 31,700 pieces of trash out of our waterways through the Pledge; and

- Hosted five river cleanups in American Rivers’ priority river basins.

That’s a lot of numbers, and just reading them doesn’t do them justice. Behind all of these statistics are people in every state who worked tirelessly to protect clean water in their neighborhoods.

So, how can we accurately represent the hours put into organizing cleanups, the communities coming together around a common cause, and the difference an individual can make for their hometown river? Pictures.

We’ve loved checking out organizer photos sent in with data results or thrown in our Virtual Landfill using the hashtag #RiverCleanup but we’re ready for more. In order to highlight the hard work of our organizers, volunteers, and supporters over the past year we are happy to announce the start of the 2016 National River Cleanup® 25th Anniversary Photo Contest!

We are accepting submissions until February 10th. At that point, we will select 10 finalists and then turn it over to the public to vote for their favorite. Make sure you check out our rules before entering. The winning photo will become the face of National River Cleanup® in 2017 and be featured on our website and in our publications. Strong contenders will highlight the volunteers and organizers who make our cleanups possible, the river they love, and their favorite cleanup finds filling National River Cleanup® 25th anniversary trash bags.

We look forward to seeing all your great 2016 cleanup photos and learning the stories behind your cleanup. Good luck!

Check out our official rules.

Guest post by Nancy Blue is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Pascagoula River.

Our journey on the Pascagoula began about five years ago and our love for the river was instant. We started off by restoring a vintage houseboat, BlueByYou, which we trailer from our home to the river. We quickly marveled as to how the time we spent on the river also restored our souls. This river was giving so much to us each time we visited that we quickly began to give back. Little did we know, BlueByYou would become a workhorse vessel for our adventure in river stewardship. Over the years, we have independently picked up, hauled home, and disposed of approximately 20 tons of river trash.

We have spent many hours enjoying the natural habitat of the peaceful cypress swamps. The serene mirror images of reflections in the water of the sky, swamps, and marshes are forever in our minds. After navigating our way through raging flood waters, we gained more respect for the power of the river.

We have seen many wonders on this river. A pair of Bald Eagles in a downward spiral locking their talons in their mating ritual. Ospreys and Great Horned Owls nesting then caring for their young. Alligators peeping out of the water and sunning on the banks. American White Pelicans migrating for the winter. These are just a few of our favorite things.

The Lake George project that would dam the Pascagoula River tributaries Little Cedar Creek and Big Cedar Creek is unfathomable. There will be huge impacts to the wetlands and streams. Big Cedar Creek is a direct tributary of the Pascagoula. The river and creek provide habitat for common species and those of special concern, including the Gulf sturgeon, striped bass, pearl darter, Alabama shad, yellow-blotched map turtles, numerous species of rare mussels, and gopher tortoises.

The remarkable experience of the Pascagoula River is as close to being an unspoiled, resilient wilderness as imaginable for this area. The Pascagoula River is truly a local and national treasure. Please join us in our efforts to eliminate this current threat.

Nancy and her husband Rick are local residents and river stewards living in the Pascagoula River watershed.

Nancy and her husband Rick are local residents and river stewards living in the Pascagoula River watershed.

Every spring as the snow melts from the Bitterroot Range along the Montana-Idaho border, the Lochsa River transforms into a raging torrent, drawing whitewater enthusiasts from across the region and around the country. It was here where I first learned to row whitewater almost two decades ago while working for Idaho Rivers United, a ragtag band of river advocates who have a penchant for playing David to industry’s Goliath.

Back in 2013, that Goliath came in the form of multinational oil companies wanting to use highway 12 along the Wild and Scenic designated Lochsa and Middle Fork Clearwater rivers (the Lochsa and Selway join to form the Middle Fork Clearwater) to transport huge pieces of equipment from the inland seaport of Lewiston, Idaho to the Canadian tar sands in northeastern Alberta. So huge were these loads that a new word was coined to describe them – megaloads – some of which are longer than a football field and weigh a million pounds.

Rafting on the Lochsa River. | Kevin Lewis

The oil companies envisioned moving hundreds of megaloads annually along highway 12, which would have snarled traffic, marred the spectacular scenery, impacted riverside campgrounds, and diminished everything that anglers, boaters, and campers love about these rivers. And it would have only been a matter of time before a megaload ended up in the river, where it would have been a logistical nightmare to remove.

For these reasons, American Rivers named the Lochsa-Middle Fork Clearwater River corridor the nation’s #10 Most Endangered River of 2014.

Given that the Lochsa and Middle Fork Clearwater rivers were among the nation’s first to be protected under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, river advocates thought the U.S. Forest Service would use its authority under the Act to ban megaloads from the river corridor. But billions of dollars were at stake for the oil companies and the Forest Service was uncertain whether it had the authority to regulate them, so it did little to stop them. That’s when Idaho Rivers United and the Nez Perce Tribe sued the agency for failing to protect river values and consult with the tribe, for whom this area has been home for millennia.

That was in 2013.

Today, we have fantastic news to report. After more than three years of federal court-sanctioned mediation involving Idaho Rivers United, the Nez Perce Tribe, and the U.S. Forest Service, a settlement was announced on January 27 whereby no future megaloads will be allowed to travel the highway 12 corridor. For anglers, river-runners, Nez Perce tribal members, and anyone who holds a special place in their heart for these magnificent rivers, this victory is as sweet as they come.

American Rivers extends a special thanks to Idaho Rivers United, the Nez Perce Tribe, and the environmental law firm Advocates for the West, without whom this victory would not have been possible.

Read more about this ruling from the Spokane Spokesman-Review at: http://www.spokesman.com/blogs/boise/2017/jan/27/megaload-settlement-some-oversize-trucks-ok-no-more-megaloads-scenic-highway-12/

To learn more about how American Rivers is working to protect our Wild and Scenic Rivers and win protections for an additional 5,000 miles of rivers to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, visit: https://www.americanrivers.org/campaigns/5000-miles-wild/.

Over the past decade, riverside towns across the country have discovered the benefits of being a “gateway” community – hosting visitors as they explore nearby National Monuments, National Forest areas, or access designated launch points for river expeditions. These gateway communities have also realized a connection to local resources by protecting and restoring rivers and streams, driving the economic engine of the region. While previously ignored, these communities have changed their outlook on rivers, understanding the benefits of a healthy ecosystem, and how recreation in river corridors can improve and sustain local economies. Communities have learned how to promote their natural amenities, and as a result have created “destinations,” resulting in evolving recreation and tourism opportunities.

To illustrate the benefits communities have discovered by protecting and restoring local rivers, American Rivers developed Ecotourism Benefits Through River Conservation – A Collection of Case Studies, a series of case studies highlighting gateway communities and how they have benefited from local river and land conservation. These towns frequently find visitors entering the communities to access parks and other recreation areas – staying in campgrounds and hotels, eating meals in town, purchasing supplies, and exploring the area’s natural and cultural resources. Learn more about these towns, and how your community can benefit by reading more here!

Each gateway community we present is unique, experiencing their own set of opportunities and challenges. However, they all share five common themes, enabling a journey towards becoming popular outdoor recreation destinations and hubs for ecotourism. Each of these themes revolve around the vital protection of nearby natural resources. These gateway communities have discovered local treasures – often hidden right before their eyes, and have embraced the evolution from an extraction-based economy to one that celebrates and sustains its livelihood through a recreation/tourism based existence.

Gateway Community Case Studies:

The following collection of case studies illustrates examples of communities developing and promoting and ecotourism ethic in communities across the country:

- Blackfoot River Valley, Montana – Blackfoot River

- Conway, South Carolina – Waccamaw River

- Duluth, Minnesota – St. Louis River

- Eagle, Colorado – Eagle and Upper Colorado Rivers

- Jackson County, Oregon – Rogue River

- Rockingham, North Carolina – Hitchcock Creek

The Illinois River begins in the Ozarks and flows 145 miles to the Arkansas River in Oklahoma. If you read Where the Red Fern Grows by Wilson Rawls as a child, you know the river – the Illinois featured prominently in the classic novel about a boy, Billy, and his Redbone Coonhound hunting dogs.

The State of Oklahoma named the Illinois a State Scenic River in 1970 because of the stream’s wildlife, recreation and scenic values.

So why did Scott Pruitt, as Oklahoma’s attorney general, sit by for years while pollution from upstream Arkansas chicken farms fouled the Illinois River? It’s one of many examples that demonstrate why Pruitt, President-elect Trump’s pick to lead the Environmental Protection Agency [EPA], is the wrong choice.

In the case of the Illinois River, industrial-scale poultry farms were spreading hundreds of thousands of tons of manure on land that drained to the river. Pruitt chose not to pursue action against the polluters. Poultry company executives were some of the most generous contributors to his campaign.

As Oklahoma Attorney General, Scott Pruitt has spent the last seven years suing the EPA to block regulations that he would be expected to enforce if confirmed as EPA Administrator.

He sued the agency to overturn the Clean Water Rule, which safeguards more than half the nation’s waterways, including streams that feed into the drinking water supplies of 117 million Americans.

He also joined industrial agricultural interests to sue the EPA to stop the cleanup of the Chesapeake Bay. EPA’s oversight is essential to the health of the Bay and everyone who lives, works and plays in the region. But again, Pruitt put the interests of polluters ahead of clean water and the people and businesses who rely on healthy rivers.

Pruitt believes in a “hands off” approach at the national level, preferring to let states sort out their own regulations. But what happens if neighboring states have different standards?

If the upstream state pollutes, the downstream state’s health, economy and quality of life suffer. It’s why we have national standards for clean water, and why we need a strong EPA to ensure they are enforced. We all live downstream.

In Where the Red Fern Grows, Billy describes his childhood home:

“Below our fields, twisting and winding, ran the clear blue waters of the Illinois River. The banks were cool and shady. The rich bottom land near the river was studded with tall sycamores, birches, and box elders. To a ten-year-old country boy it was the most beautiful place in the whole wide world, and I took advantage of it all.”

Rivers run through the lives of each and every American. They shape who we are, they are essential to our health, they are vital to our future. Whoever leads the EPA must be up to the task of protecting our rivers and clean water.

Looking at Scott Pruitt’s record, it is clear he is the wrong choice and the Senate must reject his nomination.

Guest post by Andrew Whitehurst is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Pascagoula River.

The Pascagoula River is Mississippi’s ecological jewel.

In 1994, an article in Science noted a stunning statistic — the Pascagoula is the last river of its size class in the contiguous U.S. without a dam on its main channel. Of all the large rivers in the lower 48 states, the Pascagoula River stands alone without this type of major alteration.

One Chip, Two Chips

Unfortunately, development proponents have proposed plans for creating two new dams on a Pascagoula tributary called Big Cedar Creek. Designed to form two recreational lakes, these dams are currently undergoing a scoping process with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Local government sponsors in George County, Mississippi, are pitching these recreational amenity lakes as backup water supply to the Pascagoula River during droughts. If damming happens, it will chip away at the special nature of the Pascagoula system. This threat is so great that it landed the Pascagoula on the 2016 list of America’s Most Endangered Rivers®.

Threatened Gulf sturgeon in the Pascagoula. | USFWS Endangered Species

The Pascagoula has been studied by scientists over many years. Threatened species that live in and along the river have been the subject of some of that research, including the yellow-blotched sawback turtle and the Gulf sturgeon. In addition, a historically abundant species, the striped bass has been restocked in the Pascagoula and other coastal rivers and has been the subject of ecological study. From 1997 through 1999, one group of researchers fitted striped bass with radio tags to track their movements and pinpoint thermal refuges or “cool spots” in the Pascagoula River where adult fish congregated during the summer months. Three such places were found, but the best one was upstream of the river’s tidal zone at the mouth of Big Cedar Creek. Big Cedar Creek has cool water flowing from the many springs that contribute to its base-flow. This thermal refuge was used by radio-tagged striped bass over two years to beat the summer heat. Fish are cold-blooded and regulate body temperature by seeking out water with a temperature range compatible with their metabolic requirements. That same study from researchers at Mississippi State University offered management recommendations to protect striped bass from overfishing while they congregated during the summer in cool water refuges in the Pascagoula River.

The research findings that Big Cedar Creek delivers cool water to the main river channel and that fish in the river use it to endure summer’s heat are two important reasons why altering the natural flow and function of the Pascagoula system with dams is likely to have significant environmental impacts. This is explained by considering the ecology and chemistry of reservoirs. Lakes behind dams reliably do two things: they trap sediment and they change the temperature of water released by their floodgates to channels downstream. The outfall of the lower proposed lake on Big Cedar Creek is close enough to the Pascagoula River that warmed reservoir water will likely raise the summer temperature of the cool spot in the Pascagoula at the Creek’s mouth. Just like that— the river’s best thermal refuge is lost. Fish won’t take refuge at the mouth of Big Cedar Creek in summer if the water there is as warm as, or warmer than other places in the river.

The loss of the cool spot in the river at the mouth of Big Cedar Creek is only one of many alterations that would accompany dam building. Communities should expect to see a degradation of the physical and biological quality of Big Cedar Creek, its associated wetlands, the adjacent Pascagoula River, and impacts to the species that call these special places home. Along with the proposed recreational lakes, promoted under the guise of “helping” the flow of the Pascagoula in future droughts, we can expect the loss of many of the characteristics that have made the Pascagoula River and its tributaries special.

Please take action today and let the Army Corps know that you do not support this unnecessary and environmentally harmful project. Comments close February 6th.

Andrew is the Water Program Director at Gulf Restoration Network. Gulf Restoration Network is committed to uniting and empowering people to protect and restore the natural resources of the Gulf of Mexico Region of the U.S.

Since President Trump took office on January 20, his administration has begun aggressively stripping away protection for rivers, wetlands and clean water. If successful, these actions will have lasting impacts on our clean drinking water supplies, the health of our communities, and rivers that are vital to our natural heritage and sacred to Native American tribes.

Here are five harmful actions the Trump administration took in its first week that would undermine the clean drinking water, health and safety for millions of Americans:

We all need clean drinking water. | CDC

Pledging to scrap clean water safeguards

The Clean Water Rule rule safeguards small streams and wetlands that are the drinking water sources for millions of Americans. By scrapping the rule, President Trump will make our rivers and streams more vulnerable to pollution and destructive development.

Green-lighting the Dakota Access Pipeline and the Keystone Pipeline

Construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline has already violated sites sacred to the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. The proposed route of the pipeline poses a significant threat to community water supplies in the event of a serious spill. The Keystone Pipeline would cross 1,904 rivers, streams and reservoirs. Pipelines are prone to leaks and spills, even disastrous failures. If such projects are to go forward, vigorous environmental reviews and safeguards must be in place.

Killing the Climate Action Plan

The Trump Administration erased all mentions of climate change from the whitehouse.gov web site, is vowing to stop the Climate Action Plan, and intends to double down on fossil fuel development. Allowing climate change to continue unchecked will have serious consequences for our rivers and water supplies. This means more frequent and severe floods and droughts, threatening public health and safety and our economy.

Pushing for dramatically increased energy development on public lands

President Trump is pushing for greater development of oil and gas reserves on public lands. These lands belong to all of us, the American people, and should not be turned over to energy companies. Public lands provide vital fish and wildlife habitat, recreation that drives local economies, and are the source of clean water for downstream communities.

Silencing employees at EPA and the Department of the Interior

The Trump Administration has instituted a media blackout at the Environmental Protection Agency, banning press releases, blog updates or social media posts. Tweets about climate change from the Badlands National Park’s Twitter account were deleted. Our democracy depends on the free flow of information. When it comes to protecting rivers and public health, we need solutions based on sound science and public dialogue.

Here’s What You Can Do Right Now

If all of this makes you worried for the rivers you care about, don’t give up – speak up. Call your Members of Congress. When it comes to influencing your elected representatives, phone calls can be very effective. They need to hear from you.

Tell your Members of Congress you expect them to protect your rivers and clean water. Tell them you will hold them accountable. If enough of us come together we can stop the attack on our rivers.

Guest post by Ernest Herndon is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Pascagoula River.

It was inevitable. We just can’t leave well enough alone.

The Pascagoula River has national distinction as the last remaining undammed major river system in the lower 48 states. So it’s only natural, you might say, that officials would want to “improve” the situation by damming one of its tributaries.

The “Pascagoula River Drought Resiliency Project” consists of damming Big Cedar and Little Cedar creeks to form two lakes that total 2,868 acres. By way of comparison, Okhissa Lake is around 1,100 acres, and Lake Tangipahoa at Percy Quin State Park is 700.

I’ve canoed the Pascagoula from stem to stern but had never heard of Big Cedar Creek, so I had to look it up. It enters the river from the east about halfway between Lucedale and Moss Point.

The stated purpose of the lakes is to store up water for future dry spells. That’s according to the “Joint Application and Notification” by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Mississippi Department of Marine Resources, and Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality Office of Pollution Control.

The $80 million project will supposedly benefit industry, agriculture, towns, residences, and others who use water from the Pascagoula, as well as providing recreation in the form of boating and fishing.

Critics say the lakes are a thinly disguised real estate development and will mar the Pascagoula’s distinction as being undammed, not to mention destroy lots of prime habitat.

Though the Pascagoula River itself is undammed, there are a number of manmade lakes in the watershed already, including Flint Creek Reservoir, Little Black Creek Water Park, Geiger Lake at Paul B. Johnson State Park, Lake Bogue Homa, Maynor Creek Water Park, Archusa Creek Water Park, Lake Ross Barnett (not Ross Barnett Reservoir), Turkey Creek Water Park, and Okatibbee Lake.

Lake George would be bigger than most of those and much closer to the Pascagoula River itself, as opposed to far off on the headwaters of a distant tributary.

Each side can cite a long list of arguments. But here’s the thing:

The Pascagoula River Basin is a national treasure, on a par with Florida’s Everglades, Georgia’s Okefenokee, Alabama’s Mobile Tensaw Delta, Louisiana’s Atchafalaya Swamp, and Texas’ Big Thicket.

Ecologically, it’s Mississippi’s claim to fame.

So why do we want to keep chipping away at it?

An earlier proposal, for instance, called for sucking 50 million gallons of water a day out of the river for the Richton Salt Dome. Another one, in 1999, sought to dam Bowie Creek, a major tributary.

We just can’t leave well enough alone.

The Pascagoula’s distinction came to light in the Nov. 4, 1994, issue of Science magazine, which identified the last remaining undammed, unchannelized major river systems in North America. The Pascagoula was the only holdout in the lower 48.

That’s remarkable.

I got to float the entire river in 2004. Travis Easley and I launched canoes on the upper Leaf River, while Scott Williams put his kayak in on the upper Chickasawhay. Those are the two chief tributaries of the Pascagoula.

We rendezvoused at their junction and continued on to the coast — over 200 miles and roughly two weeks. Scott and I coauthored a book on the experience, “Paddling the Pascagoula,” published by University Press of Mississippi.

On that journey we got to see what a natural river looks like, or at least as natural as it gets in the lower 48 states.

It’s far from perfect. We passed sewer pipes, cutovers, erosion and a paper mill. But mostly we experienced nature — mile after mile of woods and wildlife, the handiwork of God Himself.

So that’s why I say: Let it alone. Let’s quit chipping away at this rare treasure and focus on guarding it instead.

What You Can Do

A public scoping meeting will be held to discuss this project. If you are in the area, please consider attending.

Date: Tuesday, January 24, 2017

Time: Open house 5:00-8:00 pm (with presentation by the Army Corps at 6:30pm)

Where: George County Senior Citizens Building, 7102 Highway 198 East, Lucedale, Mississippi 39452

Ernest is an outdoor writer. This piece was first posted as a blog with the McComb MS Enterprise-Journal on October 11, 2015, and has been reposted with permission from the author.

On Wednesday I rode the train across the Yolo Bypass, which provides a glimpse of the Inland Sea that once regularly inundated the lowlands of the Central Valley

The bypass comprises 70,000 acres of farmland and wildlife areas that has been intentionally managed as a designated flood basin since 1926 when the Sacramento Weir was completed. California’s state capitol, Sacramento, could not exist without the Yolo Bypass. The bypass diverts floodwaters away from Sacramento and toward undeveloped farmlands.

Fremont Weir is a simple concrete structure that is 1.8 miles long and about 6 feet high. Note the linear concrete structure that runs from the lower left into the center of the photo.

When flows in the lower Sacramento River exceed about 65,000 cubic feet per second (cfs), they begin to spill over Fremont Weir and into the Yolo Bypass.

Water from both the Sacramento and American Rivers can also enter the Yolo Bypass via the Sacramento weir that is opened less often.

Releasing water into the bypass prevents flood stages from rising above the levees that protect Sacramento. During extreme floods, the Yolo Bypass carries five times as much flood water as the Sacramento River channel itself. Today the river is flowing at approximately 93,000 cfs at the I-Street Bridge (see photo below) while approximately 210,000 is flowing through the Yolo Bypass.

Even though the Yolo Bypass looks surprisingly full, it is only carrying about 40 percent of its total capacity. By contrast, the Sacramento River is at about 85 percent of its 110,000 cfs capacity. The National Weather Service is predicting another atmospheric river storm for next week. Thanks to the capacity of the Yolo Bypass, Sacramento will not be at risk unless the next storm is truly torrential and thanks to the new state flood plan, the bypass will someday be expanded to make sure Sacramento is protected against a changing climate.

To the south where the San Joaquin River enters the Delta, we are not as well prepared. Another big storm next week could be a big problem. Pay attention to the forecast and tune in to learn more about American Rivers’ efforts to build a new bypass on the lower San Joaquin River.

More pollution? More dying rivers? More sick kids? Not on our watch.

Wednesday is the confirmation hearing for President-elect Trump’s pick to lead the Environmental Protection Agency. American Rivers opposes Oklahoma Attorney General Scott Pruitt for EPA Administrator and we urge the Senate to reject his nomination.

Clean water is one of the most fundamental needs we have as human beings. Rivers provide most of our drinking water supplies. Clean water is essential to the health of our families. It grows the food we eat, it powers our economy and nurtures our communities.

Each and every American needs clean water. But Scott Pruitt has spent his career working against clean water. Take action today: Tell your Senators to vote NO on this nomination.

American Rivers signed a letter with over 160 other organizations opposing Scott Pruitt’s nomination. Highlights from the letter include:

“President-elect Trump’s nominee to head the EPA, Oklahoma Attorney General Scott Pruitt, has actively worked against the mission of the agency he has been nominated to lead and he should be rejected by the Senate.

“Mr. Pruitt has repeatedly sued the EPA to block clean air and clean water standards that will protect the health and well-being of millions of Americans.

“Mr. Pruitt has sued the EPA to overturn clean water safeguards for more than half the nation’s waterways, including streams that feed into the drinking water supplies of 117 million Americans. He even sued to block limits on water pollution into the Chesapeake Bay, which has no known connection to Oklahoma.

“There is a long bipartisan history in this country of supporting clean air, clean water and a healthy environment. The American public did not vote for more air and water pollution, for more pesticides in our foods or for more toxic chemicals in toys. The American people did not vote to put the EPA in the hands of someone who has recklessly worked against its mission to protect Americans’ health and the natural environment.”

Read the full letter here [PDF].

Take Action

Tell your senator that you value clean water and healthy rivers. Scott Pruitt is the wrong choice to lead the Environmental Protection Agency.

Thank you for standing with us to defend our rivers and clean water for our families, our fish and wildlife and future generations.

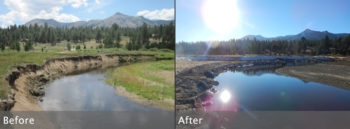

A major and long anticipated effort to restore iconic Hope Valley Meadow has been completed this fall!

The project will reduce erosion, improve floodplain connectivity and enhance aquatic and wet meadow habitat for birds, fish and other wildlife.

This effort started decades ago with an admirable grassroots effort to protect and restore Hope Valley, a beloved recreational site and fishery, and important ecological refugia.

Historically, Hope Valley was an important stopover site along the Mormon Emigrant Trail and was heavily grazed as summer pasture, which caused lasting impacts to the meadow and stream channel. The stream channel became eroded and disconnected from its floodplain, and lost much of its willow cover, reducing the meadows storage capacity, impairing water quality and degrading habitat for fish, birds and other wildlife.

In addition, Hope Valley was once threatened by a plan to dam and inundate the valley with a reservoir. Luckily, local community members and organizations, Friends of Hope Valley and Alpine Watershed Group, took action to prevent the dam and place the valley into public agency ownership. These groups have been working to restore Hope Valley Meadow by ever since, and have been planting willows to improve meadow conditions for over 20 years!

In 2011, American Rivers joined these local groups to help carry out project planning for large-scale restoration of the meadow. And now, after years of planning, major restoration is complete!

The project repaired approximately 1 mile of stream channel by stabilizing banks, planting willows and reconnecting the channel with its floodplain. This work, coupled with the activities of the local beaver population who are also helping to repair the stream channel, have set the meadow on the road to recovery.

[su_youtube_advanced url=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/VnMhEF0KbRI” width=”1000″ height=”520″ showinfo=”no” rel=”no” modestbranding=”yes” https=”yes”]https://youtu.be/mbpmAJq4XWw[/su_youtube_advanced]

The project was a highly collaborative effort that included the US Forest Service, California Department of Fish and Wildlife, Friends of Hope Valley, Alpine Watershed Group, Waterways Consulting, Habitat Restoration Sciences, Institute for Bird Populations, Trout Unlimited, Great Basin Institute and more, and received funding from six sources including National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, Sierra Nevada Conservancy, California Wildlife Conservation Board, California Department of Water Resources, Wildlife Conservation Society and Bella Vista Foundation, which contributed hugely to making it a success!