The Great Lakes – the largest system of fresh surface water in the world, which supplies drinking water to 30 million people – needs your help.

The Administration’s proposed budget has eliminated support for the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative (GLRI), which is a critical program that works to protect and restore the Great Lakes for future generations.

The GLRI, which was launched in 2010 continues to produce results.

These dollars have been used to remediate over 3.5 million cubic yards of contaminated sediment; clear more than 3,800 river miles for fish passage; double the amount of farmland under conservation practices in Western Lake Erie, Saginaw Bay and Green Bay; protect, restore, or enhance more than 150,000 acres of wetlands, coastal, upland and island habitat; and help 15 populations of native aquatic non-threatened and non-endangered species become self-sustaining in the wild. Just to name a few.

Without funding for this important work, the problems on-the-ground will get worse and become more expensive to solve.

Clean up work to remediate toxic sediment and restore habitat already underway will slow down. Asian carp prevention could leave the Great Lakes very vulnerable without funds available for monitoring and electric barriers. Targeted polluted runoff work ends, which includes projects aimed at reducing phosphorus and nitrogen inputs from agricultural lands entering waterways. Let’s not forget the Toledo Water Crisis of 2014.

Since the announcement. there has been a flurry of response to these cuts.

Congressional leaders on both sides of the aisle have expressed concern. U. S. Senator Rob Portman (R-OH) released the following statement strongly opposing President Trump’s budget request to eliminate funding for the GLRI, saying he would fight to preserve the program and its funding:

“The Great Lakes are an invaluable resource to Ohio, and The Great Lakes Restoration Initiative has been a successful public-private partnership that helps protect both our environment and our economy. According to a recent study, the GLRI’s work generates a total of more than $80 billion in benefits in health, tourism, fishing, and recreation. The study also states that GLRI saves local communities like Toledo $50 million in costs, and increases property values across the region by a total of $12 billion.

“The Great Lakes Restoration Initiative has been a critical tool in our efforts to help protect and restore Lake Erie, and when the Obama administration proposed cuts to the program, I helped lead the effort to restore full funding. I have long championed this program, and I’m committed to continuing to do everything I can to protect and preserve Lake Erie, including preserving this critical program and its funding.”

Representative Marcy Kaptur (OH-9) made the following statement:

“President Trump’s proposal cuts all funding to one of the most successful and popular clean water programs in the country,” said Congresswoman Kaptur. “Millions of Americans are depending on us to ensure safe, clean drinking water and economic growth in the Great Lakes region. Instead of bailing on the world’s greatest collection of fresh water, Congress will build on our success and work together in a bipartisan way to fight for our Great Lakes.”

Town Hall in Toledo at the Great Lakes Maritime Museum on March 9, 2017 | Lucas County Commissioners Office

Town Hall meetings and rallies have been popping up across the basin in Minnesota and Ohio. In Toledo, American Rivers in partnership with the National Wildlife Federation and the Lucas County Commissioners held a town hall to hear from concerned citizens about the proposed cuts and give them the tools to advocate individually. Local residents expressed heartfelt concern for the lakes as well as the many citizens that rely on its waters as a drinking source.

In addition to the hard court press to fully restore the GLRI, the International Joint Commission (IJC) is seeking public comment on progress by the governments of Canada and the United States under the 2012 Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement.

The IJC is an independent binational organization created by Canada and the United States under the Boundary Waters Treaty of 1909 to cooperate to prevent and resolve disputes relating to the use and quality of the many lakes and rivers along their shared border. The Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement assigns the IJC a role in assessing progress, engaging the public and providing scientific and policy advice to help the two countries restore and maintain the chemical, physical and biological integrity of the waters of the Great Lakes. The IJC wants to know what the public thinks about their progress. They are in the process of holding public meetings in various cities across the Great Lakes to get input from stakeholders like you.

If you would still like to share your thoughts on their Triennial Assessment of Progress report, you have until April 15, 2017 to submit comments.

The Great Lakes region is not just “fly-over” country. Come here and you’ll see the amazing rivers, landscapes, habitat, and people that call this place HOME(s). HOMES = Huron, Ontario, Michigan, Erie, and Superior. These are the Great Lakes and I’m proud to call it my home.

Two weeks ago as I helped my 2-1/2 year old son Owen build his first snowman and cleared the snow off the buried daffodils, I had to shush the nagging voice in the back of my head that whispered, “Is this weather normal for Pennsylvania? What will ‘normal’ be like when Owen has kids of his own?”

Out by the snow | Eileen Shader

My worries have only increased over the past two weeks as President Trump continued his attack on the environment and reversing progress the U.S. has made to mitigate and adapt to climate change. First, he released his spending priorities which cut spending on climate change because according to OMB Director Mick Mulvaney, “We consider that to be a waste of your money.”

And this week, President Trump signed an Executive Order wiping out existing efforts to curb U.S. climate emissions and federal government efforts to help prepare communities for climate change impacts.

The impacts of climate change are a long-term threat to our environment, our economy, and our national security that the current Administration is not just ignoring, but seems set on actively trying to make worse. Over the past eight years, we saw steady progress by President Obama’s administration to slow the onset of climate change and prepare communities for its impacts including floods and droughts. For anyone who worries about the future we’re leaving for our children and grandchildren, President Trump’s actions to reverse this progress is horrifying.

While President Trump’s E.O. does many things including dismantling the Clean Power Plan, it also rolls back a number of President Obama’s efforts to improve planning to reduce the impacts of climate change including floods and droughts and rescinds The President’s Climate Action Plan which was developed following Hurricane Sandy. The devastation experienced after Sandy and other flooding disasters over the past decade was a clear wake-up call that the federal government has a clear role and responsibility to help communities and states become more resilient to flooding events, particularly in light of climate change.

Even if climate change weren’t a reality, rescinding actions which are aimed at making Americans safer is simply bad economic policy. The 30-year flood loss averages calculated by National Weather Service are about $8 billion dollars and 82 fatalities per year. But that dollar figure is generally considered to be way too low and doesn’t come close to the actual cost of federal spending after a disaster.

For instance, Center for American Progress estimated that federal disaster relief for 2011-2013, including Hurricane Sandy recovery, reached $136 billion- or $400 per household per year. I don’t know about you, but I want some assurance that if I have to spend my tax dollars helping Americans recover and rebuild from floods, I want some assurance that we’re rebuilding more safely and more resiliently than we were before the flood.

While not directly addressed in the President’s E.O., today’s actions and the budget priorities indicate this Administration will not be putting a high priority on natural infrastructure approaches to flood management like wetlands, green infrastructure, and floodplain restoration rather than just traditional concrete and cement. When I began my career advocating for policies like these, any progress seemed like an add-on to make environmentalists happy. But during the Obama Administration, these approaches were on their way to becoming standard operating procedure. It had become apparent that incorporating nature into infrastructure investment is important for public safety and is a wise investment in the long run. Luckily, many states and communities around the country are proving that natural infrastructure is the future of flood management and we need to prepare now in order to deal with the increasing flood risk that comes with climate change.

It’s frustrating, infuriating, and senseless that the Trump Administration has chosen to ignore science on climate change and the many lessons that past floods have taught us. While the Administration may be too short-sighted to try to slow climate change or prepare for its impacts, the next major flooding disaster in the United States is just around the corner and the President will have to help the nation recover and rebuild. Hopefully, he will let us rebuild in smarter, more resilient manner that will leave us more prepared for the next flood.

For the sake of my kids and yours, I’m hopeful that this war on science and climate change will be short. Choosing to ignore the reality of climate change won’t stop it from happening. In the meantime, I hope communities, states, academia, the business community and others will continue to fight back by taking steps to build a more resilient future.

Flood, like fire, is important to ecosystem health but dangerous when our pride leads us to believe we can control it. Many people now know that Smokey the Bear was only partially right about forest fires. Over a century of fire suppression in the western United States has led to unchecked vegetation growth that has fueled catastrophic and harmful fires. Frequent, low intensity fires, on the other hand, are natural and reduce understory brush fuels and nourish forest soils.

Floods and flood control are very similar. Human efforts to “control” floods have mostly eliminated small to moderate flood events while potentially worsening the damage from the largest floods. Seasonally inundated floodplains provide essential habitat for fish and wildlife, but levees and dams in California’s Central Valley have all but eliminated these beneficial small to moderate floods, driving several species to the brink of extinction.

By eliminating the smaller floods that once spread out across floodplains in wetlands during annual to decadal floods, they have created the false impression that floodplains are suitable places to build new subdivisions, schools, and other public infrastructure. When large floods inevitably overwhelm the capacity of the flood system, levees break and catastrophically flood communities. We all witnessed this when Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans. Levee breaches similarly devastated some Central Valley communities in 1955, 1986, 1997, and again this past winter.

Cutting rivers off from their floodplains is very harmful and causes many problems; foremost among them is increased flood risk and habitat degradation. California’s water system was designed and built when we didn’t understand much about how rivers work. We now know that crowding rivers with levees actually exacerbates floods. Rivers need more room in order to safely and more effectively accommodate floods. This is especially important in an era predicted to be characterized by an increased frequency of extreme flood events.

A system built to rigidly withstand nature will always be brittle. By working with nature, instead of against it, we can improve the resiliency of California’s water infrastructure to more extreme floods and droughts. The recent Oroville Dam crisis highlights the inability of the West’s aging water infrastructure to protect people from floods in winter while also providing water to people and farms in summer. Managing floodwaters with natural infrastructure is the best way to protect our communities from flooding. Giving rivers more room also provides multiple other benefits including clean water, groundwater recharge, open space for recreation, and wetlands that cleanse water for fish, wildlife, and people.

The Yolo Causeway, heading west toward Davis, is surrounded by water in the Yolo Bypass. | Randy Pench

There are a couple of these noteworthy multi-benefit flood management solutions in California including the Yolo Bypass. The Yolo Bypass comprises 70,000 acres of farmland and wildlife areas that have been intentionally managed as a designated flood basin since 1926 when the Sacramento Weir was completed. California’s state capitol, Sacramento, could not exist without the Yolo Bypass. Releasing water into the bypass diverts floodwaters toward undeveloped farmlands and prevents flood stages from rising above the levees that protect Sacramento. The bypass will someday be expanded to make sure Sacramento is protected against a changing climate.

The 2017 Update to the Central Valley Flood Protection Plan also emphasizes the importance of multi-benefit flood management projects and prioritizes floodway expansions near urban areas on the lower Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers. American Rivers and our partners are now designing several of these multi-benefit projects to give Central Valley rivers more room to carry floodwaters while providing other important benefits to people and wildlife.

By working with nature, instead of against it, we can improve the resiliency of California’s water infrastructure to more extreme floods and droughts. This nature-based model of flood management is not only relevant to California’s Central Valley, but is also replicable in regions elsewhere that are dealing with outdated flood management systems and infrastructure.

Last week, Arizona Governor Doug Ducey illustrated his strong and consistent leadership in addressing Arizona’s pressing water supply needs with two significant announcements. First, Governor Ducey appointed long-time water attorney and Gila River Indian Community member Rodney Lewis to Central Arizona Water Control Board. This appointment was widely applauded across the region as a positive step, most notably as a sign by Governor Ducey that including diverse voices within the management of the water district is a key component in moving the state towards improved sustainability and collaboration, both within Arizona and with regional partners in the Lower Colorado River Basin.

Also announced last week was an innovative long-term water management agreement between the State of Arizona, the Gila River Indian Community, City of Phoenix, and the Walton Family Foundation. The Cooperative Water Conservation Partnership, as it’s been called, will continue efforts to conserve water, serving as a foundation for a flexible and resilient water supply for many of Arizona’s 6 million residents, and shows the willingness of diverse water stakeholders to come together in order to help solve Arizona’s pressing water issues, starting with the health of the Colorado River system.

Mr. Lewis is a longtime water rights attorney and member of the Gila River Indian Community. He’s the first member of an Arizona Indian Tribe to gain admission to the Arizona State Bar, and famously led the negotiations that resulted in the Arizona Water Rights Settlements Act of 2004. At a time when Arizona and it’s Colorado River neighbors are working hard to find solutions to drought and dropping reservoir levels at Lake Mead, Mr. Lewis’ broad experience will be immensely valuable to the Board.

This action by Governor Ducey is a positive step towards inclusiveness and signals a clear desire to fairly represent all Arizona water users in important, upcoming water policy decisions. Arizona tribes for a long time have shown their willingness to be leaders in water management and work with their neighbors to find solutions that benefit the Colorado River system as a whole. Mr. Lewis’ appointment to the CAWCD Board is a new opportunity for tribes to continue demonstrating water management leadership in the state.

Solutions to Arizona’s water issues will take cooperation, collaboration, and creativity. These two announcements illustrate a spirit of innovation, and urgency, that will be required to ensure the region’s water sustainability in the future. We applaud Governor Ducey’s continued leadership in Arizona water, and we look forward to working with him on these issues.

This story was developed in collaboration between American Rivers and the Environmental Defense Fund.

Infrastructure, a word that likely invokes images of bridges and roads, essential components of our nation’s infrastructure that we see every day. From cracks to potholes, we can easily judge the state of our bridges and roads. However, so much of our critical infrastructure is not visible to the eye and takes the shape of tunnels and pipes. These types of infrastructure that transport water to people across the country are also often inadequate or nearing the end of its useful life.

Across the board, our infrastructure is outdated, putting Americans nationwide at risk. Last week the American Society of Civil Engineers released their infrastructure report card and overall we received a “D+.” Our water infrastructure – which transports clean drinking water to us and takes away waste water tallied up at a “D” and a “D+” respectively. Our infrastructure challenges and the legacy of neglect leave many communities unable to provide residents with safe, affordable drinking water. Low wealth neighborhoods and communities of color, which already suffer from a dearth of investment and opportunity, are hit the hardest.

Next week American Rivers will release a new report demonstrating the importance of equitable investment in smart water infrastructure. It’s time to think beyond traditional projects like pipes and tunnels, and incorporate natural solutions into our water infrastructure. This report illustrates the importance of equitable investment in and distribution of natural water infrastructure. Case study examples from communities across the country as well as data on the economic and community benefits are highlighted.

Water treatment wetlands at Clayton County Water Authority, Headwaters of the Flint River. | Jeremy Diner

We don’t just need more investment in water infrastructure, we need the right kind of investment. Tackling America’s water infrastructure challenges presents us with a unique opportunity to foster a positive transformation in our communities. By investing in equitable, integrated natural water infrastructure we can transform and restore our living environment, invigorate the economy, and confront some of our country’s most persistent inequities. Communities across the country are proving that this model not only works, but saves money and improves lives.

By linking natural infrastructure solutions with traditional gray infrastructure, we are able to break out of the siloes that constrain cross-sector solutions, and built around equitable investment in and distribution of multi-benefit natural water infrastructure. Where our planning and decision-making tables are too small or exclusive, we must make them bigger and add more chairs. Living in a democratic society demands that we address the needs of all, and respond to historic injustices. Equitable investment is also an economic imperative: ignoring the needs of our disinvested communities will, over time, stifle overall economic growth.

When American Rivers and our partners listed the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint (ACF) River Basin as America’s Most Endangered River® for 2016, there were two major decisions that would have influenced the health of the basin’s rivers for years to come. One was the U.S. Supreme Court lawsuit, Florida v. Georgia. The other was the effort by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Corps) to update its operating manual for much of the river system.

Now there’s news on both. Within the last two months we have seen significant movement on both of these decisions – with some good news and some bad news and some more question marks for the future of this river system and the communities that depend on it.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

In December, the Corps released its Final Environmental Impact Statement and Water Control Manual for the ACF river system. The Corps operates a string of large reservoirs up and down the Chattahoochee River, including one at the Chattahoochee’s confluence with the Flint River at the Georgia-Florida state line. We and our partners made some headway with this long-overdue and critically important update to the Water Control Manual: mainly, we helped convince the Corps to use the very latest data on future water demand projections for the Metro Atlanta area. This is a win and we have you, our members and activists, to thank for it!

Unfortunately, however, the Corps’ proposed manual does little to improve river flows in the Chattahoochee and Apalachicola rivers for ecological health, recreation, fisheries, and water quality. In particular, as far as the Apalachicola River, floodplain, and bay are concerned, the Corps’ plans present essentially status quo management—and the status quo is destroying the ecological health of this once-vibrant estuary. The Corps’ plan has not been made completely final yet, but if it proceeds as written, we and our partners will still have grave concerns for the Apalachicola system at the downstream end of the ACF.

Florida v. Georgia

Meanwhile, Valentine’s Day brought a long-awaited report from the appointed Special Master overseeing the Florida v. Georgia case. Ralph Lancaster, an attorney from Maine, heard several weeks’ worth of arguments last fall, and he has recommended to the justices of the U.S. Supreme Court that they deny the state of Florida’s request to cap Georgia’s water use.

Lancaster didn’t say that Florida was necessarily in the wrong with its claims of environmental degradation due to reduced river flows. He simply said that Florida’s proposed consumption cap on Georgia might not solve the river system’s problems, depending on Corps of Engineers management—and the Corps was not a party to the lawsuit. So, he could not recommend that the Court adopt Florida’s proposal. The Supreme Court doesn’t have to accept the Special Master’s recommendation, but most observers assume it’s likely that it will.

Meanwhile, Lancaster took four pages of his 70-page report to discuss how “remarkably ineffective” many of Georgia’s water conservation efforts have been. Even where Georgia has had some success in the Metro Atlanta region, he noted, that was due to steps taken after adverse results in other legal actions stemming from the multi-decade “tri-state” water conflict with neighboring Florida and Alabama. Lancaster’s critique of Georgia’s water conservation efforts echoes what American Rivers and our conservation partners have been saying for years: Much more can be done in all three states, cost-effectively and sustainably, to protect healthy river flows in the ACF for the environment, for all basin stakeholders, and for future generations. Lancaster’s observations will no doubt be important in future phases of the so-called “water wars.”

As Atlanta public radio reporter Molly Samuel put it in a recent interview, one wonders if this latest water wars “win” for Georgia is a little bit like the Atlanta Falcons’ 21-point lead in the third quarter of the Super Bowl. It’s not that Georgia’s squad of lawyers will lose this game to Florida’s in the end; it’s just that we really don’t know, any more than we did before the Special Master released his report.

And at the end of the day, this is not actually just a “state versus state” feud. It’s an effort to find the point of balance between all of the many needs for these rivers’ waters and the aim to pass on a healthy river system to future generations. That means taking an honest look at the needs of numerous stakeholders within all three states, in urban and rural areas, and at the needs of the basin’s ecosystems. It means taking a fresh look at how we’ll manage this river system for the future. That’s no small task, but it’s probably the only way to solve the ACF basin’s problems.

Guest post by Samantha Chadwick is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness.

The Boundary Waters Wilderness’ lakes, rivers, and forests cover 1.1 million acres in Northeastern Minnesota. This amazing landscape sees paddlers, hikers, skiers, and dog teams cross its landscape in all seasons.

Faced with the threat of pollution from sulfide-ore copper mines proposed near waterways that flow into the Wilderness, supporters from across the state and even the world have rallied to urge for protection of the Boundary Waters. The Campaign to Save the Boundary Waters is leading the effort to gain permanent protection for the Wilderness. American Rivers is one of 36 groups in the coalition and helped launch this effort and bring attention to the issue when it listed the Boundary Waters region in the 2013 America’s Most Endangered Rivers® report.

Progress and Action

Earlier this winter, clean water supporters celebrated big news when the U.S. Forest Service announced it would not consent to the renewal of Chilean-owned Twin Metals’ mineral leases adjacent to the Boundary Waters, and announced the beginning of an environmental review of the watershed to determine if it is the wrong place for sulfide-ore copper mining. The Campaign to Save the Boundary Waters is proud of our efforts that led to these new developments, and we know we could not have done it without your support. Regardless, more needs to be done to achieve permanent protection for America’s most visited wilderness.

The U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management will spend the next two years studying the Boundary Waters Wilderness and its surrounding watershed to determine if sulfide-ore copper mining should be prohibited for up to 20 years. The agencies are taking public comments on the proposed protections now through August 17, 2017. Supporters can speak out by submitting a comment online. The U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management are holding a public comment meeting Thursday, March 16, in Duluth, Minnesota. We invite everyone who is able to make it to join us and voice their support for Boundary Waters protection during the environmental review.

Forging Ahead

The future of the Boundary Waters depends on those willing to speak up for this “quiet wilderness.” That’s why on February 23, Sportsmen for the Boundary Waters and the Campaign to Save the Boundary Waters launched the Boundary Waters Business Coalition.

More than 200 Minnesotan and national businesses, small businesses, outfitters, manufacturing companies, hunting and fishing businesses, and others rely on and support the world-class Boundary Waters Wilderness for employment and quality of life.

Despite our current momentum, the threat of sulfide-ore copper mining within the Boundary Waters watershed remains. We faced opposition already in 2017 when Minnesota Congressman Rick Nolan urged the new administration to rescind the recent decisions that protect the Boundary Waters. Representative Nolan’s ask to halt this existing environmental review disrupts an essential process that will help determine whether this watershed is the wrong place for sulfide-ore copper mining.

You Can Help

Now is the time to take action and speak up for the Boundary Waters! We need to work together so that hundreds of thousands of people speak out for the Wilderness during this comment period that lets Minnesota and federal decision makers know what you think they should study during the environmental review, like the sensitivity of the Boundary Waters’ clean water to pollution, the value of this place, and its economic impact on tourism and outdoor recreation.

We can’t do that without you. So join us and speak up and show your support by taking action today.

If you would like to do even more to help, join Save the Boundary Waters’ Wilderness Warriors group, which is dedicated to taking weekly action to protect this amazing canoe country.

Thank you for speaking loudly for this quiet place.

Samantha is the Deputy Campaign Manager for the Campaign to Save the Boundary Waters, which is leading the efforts to protect the Boundary Waters Wilderness from sulfide-ore copper mining.

Samantha is the Deputy Campaign Manager for the Campaign to Save the Boundary Waters, which is leading the efforts to protect the Boundary Waters Wilderness from sulfide-ore copper mining.

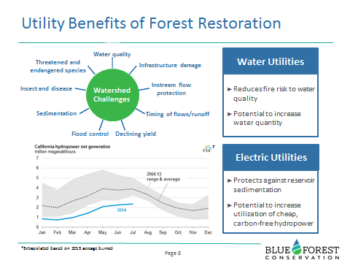

When most people think about water infrastructure, they picture reservoirs, canals, and levees. However, the forests, meadows, and snowy mountain peaks above are critical components of water infrastructure, as well. These lands form the headwater source areas that supply the water to our rivers and reservoirs.

Historically, this natural infrastructure has gone unrecognized, to the detriment of rivers and water users downstream. Luckily, managers and decision makers have begun to recognize the importance of maintaining and improving this natural infrastructure, but there is still a long way to go to catch up on overdue maintenance and to utilize natural infrastructure for maximum benefit.

California as a Case Study

In California, two thirds of the state’s water supply comes from the Sierra Nevada, the mountainous region that comprises the source of California’s major rivers. A vast network of built infrastructure called the State Water Project conveys precipitation from this region to the rest of the state. But, the headwater watersheds that feed this system have a large influence on water supply, timing, and quality, and are also integral to the long term success of the state’s water system.

For example, mountain meadows can act as natural reservoirs, moderating peak flows and storing water through the summer when the state needs it most. Forest composition and forest roads can have a major impact on sediment pollution entering downstream waterways. Improperly designed or damaged forest roads can contribute large quantities of sediment to watersheds during precipitation.

Similarly, catastrophic forest fires that occur as a result of long term fire suppression and inadequate management to reduce tree density denude the landscape resulting in major sedimentation during precipitation. In fact, boaters on the Tuolumne River in California after the catastrophic Rim Fire in 2013 said the river looked like chocolate milk due to all the sediment entering the waterway.

This is significant when you note that sediment is the number one pollutant of California waters and that much of this sediment ends up trapped behind the reservoirs of the State Water Project, reducing their capacity to store water.

California’s historical lack of recognition of natural infrastructure’s important role has resulted in a lack of resources for management and a backlog of overdue maintenance. But recently that has been changing as a number of state initiatives have begun to recognize the importance of natural infrastructure in maintaining and enhancing the state’s water supply.

For example, the critical need to improve the pace and scale of forest management for watershed health was the topic of the Sierra Nevada Conservancy’s recent Sierra Nevada Watershed Improvement Program Annual Summit.

Other recent initiatives include the 2014 California Water Action Plan, which includes objectives for headwaters improvement and meadow restoration, and the 2016 signing of California Assembly Bill 2480, which recognizes the state’s watersheds as part of its infrastructure and opens the door for conventional infrastructure financing approaches for watershed improvement.

These initiatives represent great strides toward gaining recognition for source headwater services, and ultimately toward developing a means to maintain and improve these watersheds over the long term.

American Rivers Role

In California, American Rivers has launched its first headwaters conservation program, designed specifically to protect and restore the headwater regions of California’s Rivers. Current efforts include meadow restoration, forest road repair and decommissioning, forest management, and stormwater management. We are working to build the headwaters conservation movement by piloting projects, prioritizing work, streamlining project planning, and engaging diverse partners to increase the pace and scale of watershed improvement for California rivers.

Nearly 200,000 people downstream of California’s Oroville Dam – the nation’s tallest dam – were evacuated in February when problems with the dam’s spillways triggered the possibility of downstream flooding.

American Rivers responded, calling out challenges posed by aging dams and water infrastructure nationwide. We pointed out the need for a new approach to water management: work with nature, not against it. Our message was amplified by national media outlets, sparking a dialogue about solutions that work for healthy rivers and public safety.

Here are five important lessons the nation learned from the crisis at Oroville Dam:

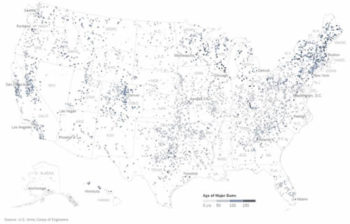

1) Oroville isn’t alone

While the events at Oroville Dam grabbed headlines, it’s not alone. As a February 13 New York Times editorial pointed out:

“Oroville is hardly an isolated case. The American Society of Civil Engineers gives the country’s dams an average grade of “D” and estimates that at least $21 billion is needed to fix aging, high-hazard dams. The average age of the country’s 84,000 dams is 52 years, and 70 percent of them will be more than a half-century old by 2020. Groups like American Rivers argue that many of these dams should be removed in the interest of public safety and to return waterways to their natural state.”

Read more: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/13/opinion/in-peril-at-oroville-dam-a-parable-on-infrastructure.html

2) There are lots of aging dams in our country, and some should be removed

The New York Times published some great maps showing the age and ownership of dams nationwide.

“It’s not like an expiration date for your milk, but the components that make up that dam do have a lifespan,” said Mark Ogden, a project manager with the Association of State Dam Safety Officials told the Times.

The paper noted the American Rivers report showing 72 dams removed in 21 states in 2016, to restore river health and improve public safety.

Check out the story and maps: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/02/23/us/americas-aging-dams-are-in-need-of-repair.html

3) We need to give rivers room

Two men watch as water gushes from the Oroville Dam’s main spillway in Oroville, Calif. | Marcio Jose Sanchez/Associated Press

Bob Irvin, president of American Rivers, published an opinion piece in the Washington Post titled “We trust dams and levees at our peril.” When it comes to improving flood safety, the best step we can take is to widen floodways and restore floodplains. He wrote:

“Indeed, to ensure public safety, we need to give rivers more room, not less. We must ensure that rivers have the adjacent floodplains and wetlands they need to move and dissipate floodwaters naturally. Dams and levees limit such options and often incentivize development and redevelopment in places most prone to damaging floods. We not only need to think twice before building dams and levees, we also need to be removing existing dams and levees that have outlived their usefulness and are threatening public safety by aggravating flood risk.”

4) We need to address the realities of climate change

It’s time to update water management to deal with the realities of climate change, specifically more frequent and severe floods and droughts. The Christian Science Monitor’s Zack Colman looked at the “rule curves” set by the Army Corps to dictate dam operations – when to fill up and release water from a reservoir.

“Not only are they for an outdated period, they are actually written on graph paper with a pencil,” says John Cain, director of conservation for California flood management with American Rivers. “They weren’t even digitally generated.”

“My concern about the rule curves being out of date is legitimate, but a terrific mitigating factor is our ability to forecast,” Cain told the Monitor. “And that is why it would be a huge disservice to cripple NOAA and the National Weather Service climate change science programs.”

5) It’s possible to find policies that provide solutions for both droughts and floods

The Yolo Causeway, heading west toward Davis, is surrounded by water in the Yolo Bypass. | Randy Pench

The Sacramento Bee published a great editorial showing how giving rivers room provides solutions for handling both droughts and floods.

“… climate experts say flood is only half the picture. Long-term drought punctuated with deluge is about to become California’s new normal, thanks to the way global warming has amplified regular climate variations. So while they’re at it, state officials should ask whether now might be the time to join nature, rather than just trying to beat it. Sure, fix the dams and levees that have shielded us from winter rains so far. But also find ways to make natural flood patterns work for us.”

The editorial calls for flood easements and levee setbacks to protect people and property, and allow for groundwater recharge and healthier rivers.

“Concrete alone won’t work forever. Where possible, maybe working with, rather than against nature, is the smarter route,” the editors write.

We couldn’t have said it better ourselves.

Read more: http://www.sacbee.com/opinion/editorials/article136322158.html

Originally published by River Network in the January 2017 Issue of River Voices.

What’s in a river?

That which we call a river, by any other name, would still be a bunch of water, critters, nutrients, and pollutants flowing downhill. Some people see a river and feel a sense of peace and relaxation. Others may see a drainage canal. A highway engineer may see a barrier to transportation while a boat captain sees a means of transportation. An ecologist sees a hotbed of biodiversity. Still others may see the entire footprint of our civilization, as the rain touches every bit of the landscape before joining forces as a river. Indeed, a river is all of these things.

To ensure that rivers continue to provide these important services, we must recognize all the benefits of water, and acknowledge that trade-offs occur as society marches forward. The recognition of these trade-offs and the distribution of benefits is often referred to as integrated water management.

Integrated water management has been described as pragmatic, adaptive, elastic, holistic, essential, costly, time consuming, challenging, unwieldy, a welcome aim, a Nirvana concept, and accepted internationally as the way forward. Despite this amorphousness, most practitioners agree on a few core principles, including:

- Water should be managed in a less fragmented manner,

- Improved collaboration is at the heart of an integrated strategy, and

- The end-goal is to improve the environmental, social, and economic conditions in an equitable and sustainable manner.

American Rivers is focused on implementing practical approaches to integrated water management which build on these core principles. Whatever you call it, many of us practice integrated water management every day.

These questions are informing our advocacy for green stormwater infrastructure around Turner Field, former home of the Atlanta Braves.

Beyond the Braves: The Future of Turner Field

The historically black neighborhoods surrounding Turner Field have endured decades of infrastructure-driven injustices. Projects such as interstate highways and stadiums have transformed a once-thriving neighborhood into a vast sea of parking lots and roads – displacing residents, small businesses, and jobs, and causing major flooding in residential neighborhoods immediately downstream.

In the wake of the Braves’ exodus, the Turner Field Community Benefits Coalition (TFCBC) surveyed almost 1,000 neighborhood residents, and determined that “A well-integrated, mixed use development” tops the list of community desires. The #1 answer to the question, “The New Development Should…” was “…manage stormwater.”

After discussing these results with the TFCBC, American Rivers considered how the benefits of green stormwater infrastructure (essentially, using plants instead of pipes to manage rainfall) could address several of the community’s top priorities beyond just managing stormwater. From there, American Rivers joined a highly anticipated visioning process known as the Livable Centers Initiative and spent the next few months attending meetings and workshops, speaking with urban planners, transportation engineers, community groups, water professionals, and various government entities. We conducted research across the country to demonstrate what others are doing, and then we developed two feasibility assessments for green stormwater infrastructure implementation as part of the Livable Centers Initiative vision.

WATER Communities

Here, ECO-Action enters the story. ECO-Action is a local non-profit focused on issues of environmental justice, and an active member of the TFCBC. American Rivers partnered with ECO-Action to develop a course for community members—the Watershed Advocate Training for Empowered and Resilient Communities, or, WATER Communities. We held monthly meetings which included lectures and discussion led by expert speakers on subjects ranging from infrastructure and environmental justice to advocacy and community organizing. As Turner Field is redeveloped, it will be crucial to have many advocates standing strong for their neighborhood.

Today, several months after the conclusion of the WATER Communities course, the trainees continue dialogue amongst themselves and are organizing to discuss the best ways to apply the knowledge they received during this course. American Rivers, along with ECO-Action and a WATER Communities graduate, will share more about this training model during the 2017 River Rally workshop, Equitable Urban Planning for Resilient Communities.

One Point Eight Inches

Nothing reflects the integrated nature of this project like that little number. After all the listening and talking and research, American Rivers recommended that the first 1.8” of rainfall should be retained onsite (as opposed to sending it offsite and downstream to cause flooding and pollution) —an ambitious, yet feasible amount equivalent to 95% of all 24-hour storms that hit Atlanta in an average year.

Onsite retention standards don’t require green stormwater infrastructure, but they drive the use of it. It isn’t perfect, but it goes well beyond the City of Atlanta’s 1.0” onsite retention requirement. This performance metric made economic sense based on common building standards, meaning that it’s flexible enough to dovetail with LEED or SITES requirements. Our recommendations would reduce the volume of runoff by 3.4 million gallons per storm in this flood-prone neighborhood.

Learn More

- American Rivers’ Integrated Water Management Resource Center provides a a framework for those seeking to practice integrated water management.

- American Rivers’ The City Upstream and Down publication detailing key takeaways for cities from national leaders on integrated water management.

- Turner Field Community Benefits Coalition—website for the primary community group advocating for equitable and inclusive development at Turner Field.

- Equitable Urban Planning for Resilient Communities workshop at River Rally 2017 in Grand Rapids, MI, May 9-11.

Then we began to share the results with stakeholders. The planners thought it was too much—would it be too costly or take up too much space? The community representatives thought it wasn’t enough—how much would this actually help the flooding? No one thought it was just right. Over time, as we discussed the pros and cons of green stormwater infrastructure, people on all sides came to embrace, or at least accept, this recommendation.

Ultimately, the Livable Centers Initiative, the City of Atlanta, and the TFCBC endorsed it. The Georgia Department of Transportation is currently using the 1.8” performance standard in a voluntary pilot project just uphill of the redevelopment site. City Council members even requested language to include this performance standard in the draft rezoning legislation for the area.

Throughout our early work using the integrated water management framework, American Rivers has been exploring what this concept can teach us. How can it make us better at protecting and restoring rivers? What should we be doing differently? This experience suggests that we start by breaking out of our own silos. We free up more evenings to attend community meetings. We trade our keyboard for a telephone or a handshake. We listen more and talk less. We practice more humility and patience.

If we can do these things, we’ll be on our way to a new answer to the question: What’s in a river?

That which connects us.

On November 9, the day after the election, I got an email from John Sherffius, an artist we have worked with in the past (he did the great illustration highlighting threats to the Grand Canyon).

He wrote that he was worried about new threats to rivers and the environment, and he wanted to help.

Several days later, he shared the wonderful illustration above that captures what we’re all about as an organization.

Our country is a nation of rivers. Rivers flow through our communities and they flow through our veins. We all live downstream and we have a responsibility to each other, and our children and grandchildren. Healthy rivers are essential to each and every one of us – for the water we drink, the food we eat, for our economy, for our health.

Thank you, John, for this gift. And thanks to all of you who have stepped up over the past three months. You have made donations. You have called your Members of Congress. Your voices matter.

We are so grateful to all of you – long-time members, and those of you who just joined recently – for speaking up for clean water and healthy rivers.

When we come together we can do amazing things, and rivers truly do connect us in so many ways. Share this graphic »

It has been a busy couple of months for America’s Most Endangered Rivers®! While we are fighting battles on many fronts, it is nice to hear some good environmental news. The stories below demonstrate that persistence pays off when partners work together to push decision-makers to do the right thing for rivers.

Middle Fork Clearwater and Lochsa Rivers – Idaho

Listed as endangered in 2014

Back in 2013, multinational oil companies wanted to use Highway 12 along the Wild and Scenic designated Lochsa and Middle Fork Clearwater rivers to transport huge pieces of equipment (“megaloads”) to and from the tar sands in northeastern Alberta, Canada. The oil companies envisioned moving hundreds of megaloads annually along Highway 12, which would have snarled traffic, marred the spectacular scenery, impacted riverside campgrounds, and diminished everything that anglers, boaters, and campers love about these rivers. Plus, it would have only been a matter of time before a megaload ended up in the river, where it would have been a logistical nightmare to remove. Consequently, Idaho Rivers United and the Nez Perce Tribe sued the U.S. Forest Service for failing to protect river values and consult with the tribe on allowing the megaload transport to continue. On January 27, 2017, a settlement was announced whereby no future megaloads will be allowed to travel the Highway 12 corridor.

Middle Mississippi River – Missouri, Illinois, Kentucky

Listed as endangered in 2001, 2004, 2014

On January 19, 2017, the Obama Administration issued a resolution to stop the damaging New Madrid Levee Project. The New Madrid Levee was a proposed part of the St Johns Bayou New Madrid Floodway Project. Located in the bootheel of Missouri, the US Army Corps of Engineers (Corps) was proposing to build a 1,500-foot levee. At New Madrid, the levee would cut off access to the last remaining naturally functioning floodplain in the region. About 70,000 acres of floodplain would be lost and about 53,000 acres of wetlands would be drained. In the resolution, the agencies agree that the only way to mitigate for the environmental impacts of the project would be to provide free and open access to another comparable section of floodplain nearby. The Corps acknowledged that, at this point, there are no other landholders willing to provide the 70,000+ acres of floodplain for the mitigation – an area that would fit Manhattan Island almost 5 times.

Rogue-Illinois-Smith Rivers; Rough and Ready Creek and Baldface Creek – Oregon

Listed as endangered in 2015 and 2013, respectively

On January 12, 2017, the Obama Administration took decisive action in adopting a 20-year ban on new mining for over 100,000 acres of public lands in the Wild and Scenic Illinois, Rogue, and Smith River watersheds, including Rough and Ready Creek and Baldface Creek in Southwest Oregon. Senators Ron Wyden (D-OR) and Jeff Merkley (D-OR) and Representatives Peter DeFazio (D-OR) and Jared Huffman’s (D-CA) have been incredibly dedicated in their years of work (in the case of Wyden and DeFazio two decades) to protect these special watersheds from industrial strip mining. Our coalition of local, state and national advocates have worked tirelessly to protect this area, especially the Klamath Siskiyou Wildlands Center, Kalmiopsis Audubon, Native Fish Society, Friends of the Kalmiopsis and the Smith River Alliance.

St. Lawrence River – New York

Listed as endangered in 2016

On December 8, 2016, the International Joint Commission announced approval of Plan 2014, which addresses water management in the St. Lawrence River Basin. Plan 2014 was developed after more than two decades of research and deliberation, a $20 million binational study, and extensive public comment and consultation with government at all levels and a variety of stakeholders. The Plan has widespread support from 22,500 citizens, 42 environmental, conservation and sportsmen organizations, and local and regional businesses. Implementation of Plan 2014 is expected to restore more than 26,000 hectares of wetlands along the St. Lawrence and Lake Ontario. In addition, it will increase hydropower production at the Moses-Saunders dam, improve water quality, support fisheries, increase biodiversity, and control erosion. Adoption of Plan 2014 is expected to provide up to $9.1 million in increased economic benefits for the region.

Upper Colorado River – Colorado

Listed as endangered in 2014

In 2014, American Rivers and our partners called for a Colorado Water Plan that promotes sustainable use of water from the Upper Colorado River Basin, without building costly, environmentally harmful, and ultimately ineffective projects on our cherished rivers. In November 2015, Governor Hickenlooper signed the Colorado Water Plan committing the state to coordinated and sustainable water management for the next 35 years. On November 16, 2016, the first anniversary of signing of the Colorado Water Plan, Governor Hickenlooper proclaimed this date as Colorado Water Plan Implementation Day. This proclamation further supports the important work that must continue to move forward goals and objectives contained within the Colorado Water Plan. The Colorado Water Conservation Board voted to secure $55 million as a part of the 2017 Colorado State Budget for implementation of the Plan.

Boundary Waters – Minnesota

Listed as endangered in 2013

On December 15, 2016, the Obama Administration denied two hardrock mining leases that could have had a major impact on the health of the rivers, fish and wildlife of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness. Through the steadfast persistence of the Campaign to Save the Boundary Waters and all of their partner groups, the Boundary Waters and its pristine rivers, abundant fish and wildlife, and world-class recreation opportunities are one step closer to being protected for future generations. In addition to denying the mining leases, the US Forest Service has submitted an application to the Secretary of the Interior to withdraw from mining key portions of the watershed that flow into the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness. Essentially, this process would allow for two years of study and public outreach and comment on the potential 20 year withdrawal from mining. This is great news!