Today’s post is a guest blog by Susan Culp, our Verde River Coordinator.

Winter rains and snowpack in the high country raise the river levels, and with the warming temperatures, river recreation enthusiasts begin flocking to the river to paddle, birdwatch, and hike.

This year, we were treated to heavier than usual winter rains, which kept the river flows relatively high compared to past years. This made for an exciting Verde River Runoff Kayak & Canoe race held on March 18th.

The higher waters meant for quicker finish times, and past participants were eager to shave time off their runs. Jeff Johnson won the men’s solo kayak division, as he has the past two years running.

Melinda Collis took first place for women’s solo kayak. Jason Kierein won in the newly created stand-up paddleboard division, and Brian and Ross Teske, and Mike & Tony Shaw, took the win in the tandem kayak and tandem canoe divisions respectively.

In May, Friends of Verde River Greenway hosted an inaugural “Verde State of the Watershed” conference to share information about local efforts to sustain river flows, restore and protect riparian habitat, and promote community connections with the Verde River through recreation enhancements and economic development.

Over 230 people registered for the State of the Watershed conference, and the auditorium at Clark Memorial Clubhouse was packed! The conference hosted panel presentations on flow restoration efforts, riparian vegetation and wildlife habitat restoration projects, and the connection of communities to the Verde River and its tributaries.

Leaders from all over the Verde Valley spoke passionately about the Verde River and what it has meant to them in their communities – including Yavapai Apache Elder Vincent Randall, Camp Verde Mayor Charlie German, Clarkdale Mayor Doug Von Gausig, and Cottonwood Mayor Tim Elinski. The conference was attended by many more elected officials from the Yavapai County Board of Supervisors to city and town Council members, and staff from Congressman Tom O’Halleran’s office.

Sarah Porter, the Director of the Arizona State University’s Kyl Center for Water Policy, gave the keynote address titled “The Price of Uncertainty,” which discussed Arizona’s general stream adjudication and the challenges it causes for water rights certainty and water management. Participants in the conference were also able to discuss specific projects in small-group settings at the Watershed Café topic tables.

It was a highly successful event, which American Rivers was honored to help sponsor, and demonstrates how far the Verde River watershed has come in advancing sensible and practical solutions and on-the-ground projects to protect the Verde River, and the level of support and awareness in the community for the importance of one of the last remaining healthy desert rivers in Arizona.

Photo Credits: Verde River, Susan Culp

Guest post by Mitch Reid, Program Director at the Alabama Rivers Alliance, is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Mobile Bay Basin.

For years, the Alabama Rivers Alliance and our partners have been working to get Alabama to develop a statewide water management plan that protects the flow of water in our rivers and streams. This effort really ramped up in April of this year when, on Rivers of Alabama Day, American Rivers listed the Mobile Bay Basin as one of America’s Most Endangered Rivers® due to a lack of water planning.

In response to this designation, people from all over the state, and indeed the country, have taken up the call for Alabama to do a better job at managing its water resources. This message was front and center as we visited state legislators on Rivers of Alabama Day and, in response, State House Representative Patricia Todd filed the Alabama Water Conservation and Security Act (HB577). This important piece of legislation requires the state to balance water uses with the needs of the rivers to ensure they remain clean and functioning, and it defines the flow conditions during which the state must enforce limits on water use in order to protect all users and the rivers themselves. The support for this bill from the conservation community has been robust.

Even though the bill was filed late in the session, Representative Sessions, Chair of the Alabama House Committee on Agriculture and Forestry, has decided to take it up and hold a hearing to discuss the issue. The hearing is set for Wednesday, May 17th, at 9 AM in Room 410 of the Alabama Statehouse. Anyone who is interested is welcome to attend.

Alabama Rivers Alliance and partners lobbying for Rivers of Alabama Day and America’s Most Endangered Rivers Day. | Alabama Rivers Alliance

Alabama Rivers Alliance will be at this hearing to speak and we would love to have your supportive faces in the crowd. While it is too late to pass this legislation during the current legislative session, this hearing will be an important opportunity to inform the committee about the status of water planning in Alabama and the need to protect our rivers. We anticipate that this hearing will spur conversation throughout the summer (including during American Rivers’ Mobile Bay Basin Rivers Month), and we intend to bring the legislation back next year.

We appreciate the work that Alabama House Representative Todd, Representative Sessions, and Speaker McCutcheon have done on this issue.

Last month, at an event described as a “White House CEO Town Hall,” President Donald Trump told an astonished public that he wants to trim the permitting process for new dams down to four months.

That’s less than half the time that a sixteen year old needs to have a Learners’ Permit before applying for a Maryland Driver’s License. That’s shorter than professional football’s regular season. It’s the length of a kindergarten year, if your child attends a half-day program not a full day program.

Luckily, the President’s advisors appear to have talked him down from this position, and he’s settled on a one-year permitting process for building new dams.

That’s one year to collect and analyze data about the seasonal flows of the river. One year to look at the migration patterns of fish and birds, and other wildlife that depend on the river. One year to study and analyze the sediment that will inevitably collect behind the dam, threatening water quality. One year to make sure the dam is designed safely to ensure that people downstream don’t have to live with the threat of a leaking time bomb. One year to consult with states to make sure that state water law and water rights are respected. One year to consult with Native American tribes to make sure that their lands and resources are protected. One year to make sure the dam will have no negative impacts on lands or structures owned by the taxpayers. And one year to write up all these analyses, ensure the dam builder complies with the terms necessary to protect the public interest, and then issue the permit.

Maybe it made sense to a room full of CEOs, but you and I know that this idea doesn’t make sense.

Rivers have different flows at different times of year. You measure them for the whole year, and then you measure a couple of other years so you have an adequate sample size. It can take a year or more just to untangle water rights. Studying sediment isn’t easy, and it is time consuming. And before we allow a big corporation to flood a Native American reservation, we ought to give the tribe an opportunity to have their voice heard, and to collect the data they need to make their case.

In December 2015, the U.S. House passed legislation that was endorsed by the National Hydropower Association, which is made up of big companies like Exelon, Duke Energy, and Southern Company. The bill (H.R. 8) would allow the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) to override states, tribes, and federal natural resource agencies if FERC thinks they’re taking too long.

The reason that legislation didn’t become law? River advocates fought like hell. So did states and tribes. We pounded the Hill, telling Senators that this was a bad idea. We told the White House that President Obama should veto this if it ever gets to his desk, because if he didn’t, he could be condemning the country to dried-up rivers and dead fish.

President Obama heard our voices and threatened to veto this legislation. The Senate refused to take it up. President Obama has moved on. But American Rivers is still here.

We know that the hydropower industry will do what they can to win this. But so will we.

We’re not going to let President Trump achieve his vision of a bunch of new dams built on your rivers. Not without a fight anyway.

Last month, President Trump talked about hydropower. He said it was “great.” Actually, he said it was “great, great.” He said “It’s one of the best things you can do – hydro.”

No, it isn’t.

There is a place for hydropower. But weakening safeguards at hydropower dams is a bad idea. And building new hydro dams would come with extremely high costs and would take our country backward, not forward.

Why doesn’t it make sense to build a bunch of new hydropower dams?

- All the good spots are already taken.

- Healthy rivers are our natural defense against climate impacts.

- Hydro dams and their reservoirs can contribute to global warming pollution.

- Dams damage rivers.

The focus on hydropower in the coming years must not be on building new dams, but instead on maximizing efficiency, responsible operation, and environmental performance.

Here are three things President Trump should know about rivers and hydropower:

1. Rivers are great

Clean, free-flowing rivers are vital to the health and well being of each and every one of us. They provide our drinking water, grow our crops, nourish our communities, and fuel our economy. “America is a great story and there is a river on every page,” wrote the late journalist Charles Kuralt. We need to focus our investments on restoring river health, not on weakening safeguards or building more hydropower dams.

2. Dams hurt rivers

A river is supposed to flow. A dam blocks that flow, with major consequences for water quality, fish and wildlife, recreation, cultural resources, and all of the people who depend on a healthy river. Dams are a big reason so many fish and other freshwater species are endangered. Many communities are choosing to remove outdated dams – just last year, 72 dams were removed across 21 states, restoring 2,100 miles of rivers.

3. Last-century energy = losers

Quite simply, dams are 19th century ideas. We need 21st century energy solutions that safeguard rivers and clean water, our most precious natural resource.

There are efforts in Congress to weaken or eliminate clean water protections and other safeguards at hydropower dams. This is about whether states, tribes and citizens will continue to have a say in how dams are operated. It’s about the future of dammed rivers nationwide.

Throughout our history, American Rivers has defended rivers from harmful dams. We’re not backing down now. Whether it’s fighting new boondoggle dam proposals or upholding key safeguards for rivers and communities, we’re going to keep fighting for the rivers that connect us all.

Guest blog post by Cate Sutz, owner and operator of Dog Boarding of Myrtle Beach.

So, you have been enjoying your time on the river with your standup paddle (SUP) board. You have gotten over the wobble of finding your balance and are now well acquainted with your equipment. You have discovered several beautiful places that you would like to share with others. The time paddling has been refreshing, peaceful, and fun but on certain days it just seems to be missing something. Why not try bringing your dog along on your paddle board outings? There is much joy, satisfaction and adventure waiting for you this year on a SUP with your pup!

There are so many great places along the slow-moving river systems and National Wildlife Refuges that are perfect to share with your dog. One place in particular I have found to be perfect for a day out with the dogs (and people of course) is the Waccamaw River. The beauty of the blackwater along with the peaceful meanderings of this mellow river as it fills in the gaps between the knees of the Cypress is captivating. There are plenty of branches, lakes, and loops off the main river that will allow for all kinds of adventures. The clean water and pristine river allows for awesome recreational opportunities. If your dog already enjoys going along, then going with you on your paddle board on the Waccamaw is just the excursion you need to try.

It is best to make this a fun process for your dog with lots of games and rewards and the Conway Riverwalk Area provides ample space and opportunity to do this. There are a few options for launching which makes this ideal for trying SUP with your pup. There are public floating docks, a soft launch, and even a marina. The Waccamaw National Wildlife Refuge is also hoping to open a new public access spot in downtown Conway in May with ample parking and a kayak launch. Paddling with your pup will feel natural in no time and the Blue Trail marked along this portion of the Waccamaw will be the perfect map to fun times together. (You can also check out the full Waccamaw River Blue Trail map at: www.AmericanRivers.org/WaccamawBlueTrailMap)

Follow along to learn more about paddle boarding with your dog.

Safety Notes

- Make sure your dog knows how to swim. Test him in a safe environment where you can touch the bottom and hold him up if needed. If your dog is not physically active and does not enjoy a water environment, you may want to reconsider.

- Make sure your dog obeys basic commands on and off leash. Sit, stay, lay down, come. These are all important commands to know when you are paddle boarding with your dog.

- Find a Canine floatation device that works for your dog. A handle on the back is a helpful tool to assist the dog up on to the paddle board when you are already on board.

- Be sure the board you use has a volume that will carry the weight of you, your dog, and any equipment you plan to bring along. Check your board brand website for details on maximum volume.

How do I get my dog to like the paddle board?

Betty getting ready for her first SUP session on the Waccamaw Riverwalk in Conway, SC. | Grace Sutz Photography

A dog on a paddle board with you is probably not a natural thing for either of you. Make sure you take the time to get acquainted. Know your board and limitations. Know your dog and his limitations. You can absolutely teach an old dog new tricks. Take your time and your reward will be a dog that loves to paddle down the river as much as you do.

If treats motivate your dog, this is probably going to be easy! Stay focused but be flexible. Keep your eye on the goal, but don’t keep trying the same thing over and over if it just isn’t working. Use variations of the steps below to cater specifically to your dog.

Start by putting your board in a location that your dog walks by it several times per day. The more he sees it, the more familiar it will become.

After it seems like the paddle board is invisible to him, place it next to the dog’s bed or favorite resting area. Sit on it while your dog is near. Make it seem like a normal piece of furniture.

Another day or so later lay the board flat on the floor and place a treat on it. Gently reward the dog with praise when he takes the treat. Good boy!

Next, stand or sit on the board and invite the dog to sit with you. Offer the treat and praise when your dog is successful.

Repeat any of these steps as many times as needed to get your dog comfortable with the board and being on the board. Some dogs accomplish all of this in an hour, some dogs it will take a few days. Take your time because moving forward too fast can make it harder or even impossible!

TJ takes the nose as he enjoys paddle boarding with his owner wearing his canine flotation device. TJ is a veteran SUP Pup and enjoys the lakes and rivers of SC. | Jennifer Graham

Take the board outside. Repeat any of the steps needed that allow your dog to accept the board in this new environment.

All along the way, you are going to want to go ahead and get your dog used to the flotation device as well. Slip on the device before going out for a fun walk, so just like when you grab the leash and your dog perks up because he knows a leash in your hand means fun walk outside with you this will give your dog a clue that you are about to go do something enjoyable and that flotation device is part of the fun!

And now you have done great prep work and your dog is ready to head to the water. He knows how to swim, is use to his flotation device is comfortable with your paddle board, and is excited about going with you! You have it all covered so far so pack a snack bag with water and treats and go launch!

Selecting a good launch area for your first SUP pup sessions.

Once you accomplish acceptance of the board, you are ready to hit the water! This is an exciting day and you are no doubt going to be quite gung ho over the whole thing. Your dog will sense your excitement and be thrilled to be out on an adventure. Remember, you want your dog to be focused on you so a pre-paddle run or full on play session would be a great precursor to the SUP session. The more relaxed and focused your dog can be, the better. I always suggest making the trip as “normal” as possible. A successful first session starts with a relaxed dog and a great launch area.

So, walk around the area first before unloading your board. Take time to let the dog recognize your board in this new place. Offer assurance and rewards for any hint of curiosity or acceptance of the activity.

Betty getting her balance and starting to feel confident with the movement of the board. | Grace Sutz Photography

I love to launch my paddle board sessions out of Conway at the Riverwalk area. This location is relatively quiet especially on weekdays and I can give the dogs time to walk around, sniff, run, and relax. There is not much boat activity either which is really helpful on your first few outings. The Kingston Lake area is very calm with little current which is great for a quick swim and refreshment. Once you paddle under a railroad tressel or two, there are virtually no motorized vehicles to be found. This place is so beautiful and quiet. Great for the beginner paddler, this area is part of the Blue Trail and is well-marked with signs and information. You can take your dog on a nice paddle through the history of Kingston (now Conway) and the river that played a major role in the growth and development of this area.

Look for these qualities when selecting the place for your first outing:

Try to find a quiet launch with little activity. Choose a place with low human activity and few distractions. Boats coming in and out of a marina cause a lot of wake for a dog’s first water experience on a board, so finding a low activity launch is a good idea. Look for a soft launch on a quiet bank. The 140 miles of the Waccamaw River provide many other launch options. Try Lake Waccamaw, Babson’s Landing, Lee’s Landing, and the Waccamaw National Wildlife Refuge’s Cox Ferry Recreation Area.

Shallow water where you can walk beside the board will help with the first session. If you can find a sandy bottom area about 3 feet deep that would be perfect! Seeing eye to eye with your dog will put you close so he feels confident. Just find the best you can, even a pool works if you have access.

Betty had a great first paddling experience. She learned everything in one afternoon! This is going to be a fun season ahead having her on board with me! Peace, Paddles & Dogs! | Grace Sutz Photography

Have those treats handy for rewarding your dog while he is on the paddle board! Positive reinforcement is the key. Bonding and connecting the board with rewards is going to be important when launching in different places and situations.

You have done it! You and your dog are now confident and able to go on the river together on your paddle board and enjoy time together in a beautiful setting. Make sure you take time to look for Bald Eagles, River Otter, and the diversity of wildlife the Waccamaw River cultivates. Our River is teeming with wild creatures and beauty. Being able to share this with your dog makes it even more special.

Have fun and then invite some friends!

After the first few sessions and a little practice getting on and off the board together, you are primed for many hours of SUP adventures with your dog. Take short trips close to the shore line for your first few outings. Build up distance and length of sessions over time. Once you are both comfortable, the possibilities are endless and so is the joy and satisfaction of having your furry best friend along for the ride on the water ways. Many people never try because they think they can’t teach their dog to stand up paddleboard but there is no big secret, just perseverance and reward!

Other Helpful Tips:

- For longer trips remember to bring water to drink and a snack for both of you. You can even start a group that can meet regularly and paddle the rivers together.

- You can add a traction pad to the nose of your board or where ever your dog finds to be most comfortable.

- Larger boards will provide greater stability. Check the volume of your board before attempting to add a large dog to your SUP adventures.

- Be sure your dog is wearing his collar and identification tags. If he accidently gets separated from you in the wilderness, anyone will be able to find you and get him home.

- Make sure your dog is healthy and up to date on vaccines as some stagnant waters can contain bacteria that may make your dog feel ill if ingested.

- If you don’t feel confident or would like a group setting for your SUP pup training, there are many reputable programs that will work with you and your dog on learning to SUP.

Cate Sutz, her husband and their 3 teenagers are the owners of Island Inspired Board Company located between the Inter Coastal Waterway and The Waccamaw River in Conway, South Carolina. They have also owned and operated Dog Boarding of Myrtle Beach for the past 7 years (www.dogboardingofmyrtlebeach.com). Cate is always looking for creative ways to combine her love of animals, paddle boarding, and people. Teaching people how to SUP and SUP with their pups just comes naturally.

You can find her most often paddling with groups of new friends along the Waccamaw River in the Conway area or handling operations at either business. Island Inspired Boards are hand made in Conway and sold in many places along the east coast and online at www.islandinspired.com.

On a March day in 2009, nine years after Chewacla Creek dried up, I stood in the roadside weeds near a county road bridge in Alabama. The creek—the city of Auburn’s water supply—was flowing again, thanks to legal protection. I was wiggling first my legs, then my arms, into a borrowed wet suit. The zipper gaped like an open shell, displaying my pregnant belly, almost four months round. With effort, I zipped up the two halves, encasing myself. My first child would dangle below me while I snorkeled—something I’d never done before.

I had joined this Auburn University field crew on a whim, based on a last-minute invitation. One these biologists was my husband, Andrew. He watched his whole family squeeze into my wet suit, then pointed us toward the creek.

We thrashed along, dropping down a steep bank, departing the road where it headed over the bridge. Stepping into the creek, we spread out and moved upstream, away from the bridge where we had parked the truck. I sank to my knees, letting cool water flow over my thighs. It was shallower than a bathtub. When I eased forward onto my hands, the water didn’t even cover my back. Biting the snorkel mouthpiece, I submerged my head through a layer of crisp-edged leaves and into another world.

We thrashed along, dropping down a steep bank, departing the road where it headed over the bridge. Stepping into the creek, we spread out and moved upstream, away from the bridge where we had parked the truck. I sank to my knees, letting cool water flow over my thighs. It was shallower than a bathtub. When I eased forward onto my hands, the water didn’t even cover my back. Biting the snorkel mouthpiece, I submerged my head through a layer of crisp-edged leaves and into another world.

The creek filled my wet suit and filled my ears, dimming other sounds, gurgling through my head like a pitcher pouring into an endless glass. I reveled in the bright underwater world, delighting at each colorful darter slipping in and out of view. I grazed my belly upstream into better visibility, moving slowly to the rhythm of my breath whooshing up and down my snorkel.

Then I lifted my head and realized I had fallen well behind the others. I slurped myself to a standing position and waded toward the bank. They had told me that the creek’s edges often held many hidden freshwater mussels. Finding those mussels was our purpose for snorkeling Chewacla Creek in March.

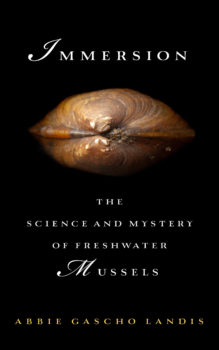

I refocused, remembering photos I’d seen, and tried to imagine our quarry. These are not the coal-black ocean mollusks clinging like butterflies to rocks or jumbled on plates under decadent sauces. Neither are they the notorious zebra mussels, Dreissena polymorpha, invasive species plaguing rivers and lakes north of here. The family Unionidae, native freshwater mussels, lives in creeks and rivers and includes almost three hundred species in North America. Nearly 70 percent of them are imperiled.

These freshwater mussels live mostly buried. Their shell edges are parted like a surprised gasp, exposing two apertures. One intakes and the other releases water, which is how mussels eat, breathe, and even gather sperm to meet their eggs. Those apertures actually look like Georgia O’Keefe paintings—flowers, female anatomy—elegant ovals decorated with variously shaped and colored papillae. Apertures, papillae, curve of a shell. This is our search image.

We stood in our wet suits, leaning toward the creekbank. Andrew pointed; I struggled to see what he described. Between my protruding abdomen and taut wet suit, I couldn’t bend my waist, so I bent my knees and tipped forward.

“She’s displaying,” he told me. He waited while I stared.

Then the mussel seemed to materialize, differentiating from the leaves and rocks. Before my eyes, the creek bottom gained a dimension as I perceived its complexity. A little spectaclecase, Villosa lienosa, was doing the work of a freshwater mussel—filtering. She was also doing the work of many females this time of year—displaying. Her gills bulged with offspring that she’d brooded for months. Now the time had come. Above those offspring waved her mantle lure, decorated with multiple tentacles that looked like a clump of small black worms. The bait.

Ripe with progeny, the female mussel must attract a fish to deliver her babies into the world. Striking the bait, a fish will release thousands of these larval mussels, which will hitch a ride on the fish’s gills, transforming into independent juveniles and then letting go and sinking into their new creekbed lives. I was impressed. Delivering offspring into the world clearly demanded heroic efforts.

I recognized this turning inside out for the next generation. This mussel and I were similarly vulnerable, preparing to empty our bodies into the future. Watching a wild mussel display her lure opened a door in my mind, like my first kiss. I became a freshwater mussel groupie. I fawned over their photographs, mussels ranging in size from thumbnail to dinner plate, building glassy or ridged or pimpled shells that are brown or black or yellow, with or without dark stripes fanning across them, and always paved inside with pearl—white, pink, deep violet. I stalked them from a distance, writing their names in my notebooks: fatmucket, pistolgrip, heelsplitter, shinyrayed pocketbook, spectaclecase, pigtoe, snuffbox. I pored over their bios. Posters of mussels hung in our bedroom.

Mussels ingest particles suspended in water drawn across their gills, which sort particles as edible or inedible. The water flowing in Alabama’s creeks and rivers, the water sitting in catfish ponds and reservoirs, the water gushing from my own faucet has probably passed through the interiors of freshwater mussels. As they filter feed, mussels also ingest contaminants into their sensitive bodies. Mussels burrow at the intersection of water and earth, so they suffer with disruptions to both creek channel and water. Their life cycle requires fish to host their parasitic larvae, linking mussels to vulnerable fish diversity. In these ways, mussels embody the whole river.

Mussels’ peril is our own. We need the same thing—plentiful clean water in healthy creeks and rivers. I think of mussels as I watch the kitchen spigot run. I heed their dwindlings and extinctions as a smoke detector piercing the night. Feel alarmed, they insist. Get up and look around. The house just might be on fire.

Adapted from Immersion: The Science and Mystery of Freshwater Mussels

Abbie Gascho Landis

© Island Press

http://islandpress.org/book/immersion

Abbie Gascho Landis is a writer, veterinarian, and naturalist. Her book Immersion: The Science and Mystery of Freshwater Mussels (April 2017, Island Press) is an invitation to see rivers from a mussel’s perspective. Landis has won Duke University’s Center for Documentary Studies 2015 Essay Award, an Arthur DeLong Writing Award, and was a finalist for the Constance Rooke Creative Nonfiction Award. Landis holds a bachelor’s degree in English and biology from Goshen College and a doctorate in veterinary medicine from The Ohio State University. Her writing has been published in Pinchpenny Press, Full Grown People, and Paste Magazine. She and her family live on a farm in Upstate New York.

Abbie Gascho Landis is a writer, veterinarian, and naturalist. Her book Immersion: The Science and Mystery of Freshwater Mussels (April 2017, Island Press) is an invitation to see rivers from a mussel’s perspective. Landis has won Duke University’s Center for Documentary Studies 2015 Essay Award, an Arthur DeLong Writing Award, and was a finalist for the Constance Rooke Creative Nonfiction Award. Landis holds a bachelor’s degree in English and biology from Goshen College and a doctorate in veterinary medicine from The Ohio State University. Her writing has been published in Pinchpenny Press, Full Grown People, and Paste Magazine. She and her family live on a farm in Upstate New York.

President Trump is spending the 100th day of his presidency in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Harrisburg lies on the banks of the Susquehanna River, which American Rivers named one of America’s Most Endangered Rivers last year.

The reason for the listing? The Conowingo Dam, a massive hydroelectric dam that alters river flow, blocks fish, and adversely impacts water quality, harming the Susquehanna and the Chesapeake Bay downstream.

Just a couple weeks ago, Trump talked about hydropower at a meeting of business leaders at the White House. He said it was “great.” Actually, he said, “It’s one of the best things you can do – hydro.”

Does the president know what’s happening at Conowingo Dam?

The Exelon Corporation is seeking a new 46-year federal license to operate Conowingo. Provisions in the federal Clean Water Act give Maryland the authority to require Exelon to meet state water quality standards.

However, there are efforts in Congress to take away that authority to hold Exelon responsible for addressing its share of the environmental problems plaguing the Susquehanna River and the Chesapeake.

Since its construction in 1928, Conowingo Dam has trapped pollutants in its reservoir. Today, scientists warn that the reservoir is essentially full, and the dam’s long-term ability to trap pollutants is exhausted. During flood conditions caused by large storms, strong river currents can scour sediment from the reservoir, sending additional pollution into the river and downstream into the bay.

As the largest source of freshwater to the Bay, the health of the Susquehanna is vital to the Bay’s clean water, fisheries, and economy.

If Congress takes away Maryland’s authority to hold Exelon accountable as the company pursues relicensing, Pennsylvania farmers and residents will have to do more to protect the Bay while Exelon is let off the hook.

“We cannot let the hydropower industry avoid its responsibility for protecting the environment at the expense of clean water, fish, wildlife and outdoor recreation,” said Bob Irvin, president of American Rivers.

Mr. President, if hydropower is so “great,” then why does it need an exemption from the Clean Water Act? If you really care about Pennsylvania, please oppose the hydropower industry’s attempts to avoid responsibility for the impacts of dams like Conowingo.

“[More recent] Presidents have used the law that we used from 1907, the Antiquities Act, to encompass very wide areas of ocean property – many archipelagos and things which enclosed many more acres than I encompassed – but mine was on land.” – President Jimmy Carter

157 million acres of preserved land is certainly not something to scoff at, and Jimmy Carter accomplished that and more with a single stroke of a pen. He also vetoed more than a dozen dam projects across the country as President, and even before then, as Governor, had vetoed a controversial dam project in Georgia. But when people think of “environmental Presidents,” they recall Roosevelt (yes, both of them), or George W. Bush, or Barack Obama – but rarely is Jimmy Carter’s name in the mix. It should be.

During Carter’s tenure in the White House, his administration designated more than 40 new Wild and Scenic Rivers, protecting over 5,300 miles of what can be thought of as our National Parks for rivers. And like our actual, terrestrial National Parks, so many miles of rivers (of the nearly 3-million miles of river across the nation) are left without adequate protection. On his last day in office alone, President Carter protected over 1,300 miles of Wild and Scenic Rivers across the country, nearly 10% of our current Wild and Scenic inventory. He took action to affirm his main conservation motivation as “…trying to preserve as much as [he] could of the beauty of God’s world.”

Understanding this about President Carter, and later learning that his “whitewater mentor” who sparked his discovery of the power and joy of a wild river was none other than American Rivers co-founder Claude Terry, we had to tell this story. And tell this story we did, in the form of our new film, The Wild President. With support of NRS and Yeti Coolers, we sat down with Claude Terry, President Carter, and Doug Woodward (from The Important Places) and explored each of their thoughts about the preservation of wild rivers, the excitement of southeastern whitewater, and the thrill of a particular day in 1974 when President Carter and Claude Terry ran the first descent in an open-water canoe of the Chattooga’s most famous rapid, Bull Sluice. We also spent a few days on the Wild and Scenic Chattooga, exploring some of the incredible shoals, slips, and rapids that make this southeastern river such a treasure.

As I spoke with President Carter in his Presidential Conference room at the Carter Center in Atlanta, I came to realize that this humble and caring man, while receiving enormous credit for his post-Presidential efforts around human rights and world peace, was also one of our more unsung environmental heroes. Whether by preserving large tracts of land for all of us, and all creatures to enjoy, protecting our best rivers, or stopping boondoggle dam projects, President Carter deserves great appreciation from each of us who enjoy clean water and wild, free-flowing rivers.

With the 50th anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act approaching in 2018, American Rivers and our partners are aiming to protect 5,000 miles of Wild and Scenic Rivers nationwide. We’re also collecting and sharing 5,000 personal river stories, to demonstrate broad support for river protection to decision-makers. “The Wild President” is one of these stories. I hope the film inspires us all to join with President Carter, and all Americans, to preserve even more of the beauty that he realized more than four decades ago.

In another installment of our American Rivers film series, we are thrilled to introduce our latest release, Milk & Honey (or Leche y Miel in Spanish), and like a number of our more recent films, Milk & Honey is simply a great piece of work. But unlike most of our films, this story takes a different approach to the message we usually tell about a river or a place. In Milk & Honey, we have very few shots of a wild, meandering river, and there are no kayaks or fly fishermen or waterfalls. In fact, in this 14-minute piece, there may be less than 30 seconds of actual footage of the Colorado River. But film makers Justin Clifton and Chris Cresci, along with photographer Amy Martin, craft a sincere and beautiful piece that we are so proud to share with you.

What this film does so well, and how it touches the viewer so perfectly, is that it is all about people – and how the people of Yuma, Arizona are so deeply connected to the Colorado River and the work that they and the Colorado River do together. In nearly every aspect of their lives, the people of Yuma are inherently tied to the health and sustainability of the river, and as we learn in Milk & Honey, the rest of us across the country are as well.

The film arcs across a typical Arizona day – we rise early in the morning with a pre-dawn wake-up call and drive to work as the sun warms the sky. We see a farmer preparing his tractor, and starting his day in the field, and we hear how appreciative he is to be in this place. In this time. Literally in the land of Leche y Miel. We then explore a Latino church, and get a peek into a sermon focused on the Colorado River, – the Pastor imploring his congregation to take responsibility and care for the river that takes care of them.

Louis Gradias reflects on life and legacy of the Colorado River from his home in Gadsden, Arizona. | Amy Martin

Next, we head to the home of a life-long historian, who has recreated scenes from the town he grew up in, Gadsden, Arizona, in his back yard (including an escaping lady of the night). He reflects on his grandmother riding on paddlewheel ships all the way up the Colorado Delta, but now to cross the river, one only needs a tall pair of boots. We then end the day back with the farmer and his family, having dinner together as the sun slides behind the western horizon once again. Finally, on the Sabbath, we watch one of the most important rituals, a baptism, cleansing these people in the waters of the Colorado River.

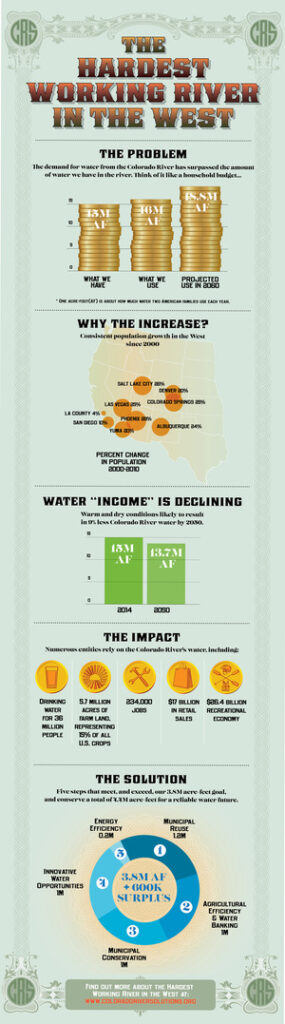

Milk & Honey may not be your typical “river” film, but that is kind of the point. We are all tied to these rivers, whether you play on them or not. Our nations rivers provide clean water, provide thrilling recreation, provide beauty and solitude and spirituality, and as this film illustrates so well, they provide our food. The Colorado River is the hardest working river in the west, and I sincerely hope you enjoy this reflection on the river that does so much for all of us, wherever you may be.

The stories are everywhere – record precipitation and snowpack in California, atmospheric rivers crashing across the Pacific Northwest, and lingering above-average snowpack across Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming. And while short-term relief is welcome, we shouldn’t break out the party hats quite yet. As Mother Nature often shows us, we never really know what is right over the horizon – we need to be prepared.

We still have a long way to go before taking our foot off the gas in encouraging everyone across the Colorado Basin towards greater conservation measures, smart water sharing agreements, and stabilization of the system overall.

Certainly, California’s statewide snowpack numbers are great – over 160% of average in early April – even inspiring Governor Jerry Brown to recently declare the end of the current drought. Upper Basin states are rolling in the numbers as well – the Colorado River basin is currently at 122% and every major river basin in Utah is at or above historical average. But not to throw a wet blanket over this year’s good news, we still have a long way to go before taking our foot off the gas in encouraging everyone across the Colorado Basin towards greater conservation measures, smart water sharing agreements, and stabilization of the system overall.

The Colorado River is currently over allocated to the tune of more than a million acre feet (one acre foot is about 325,000 gallons) per year – there is physically not as much water in the river as is being taken out. The main storage reservoirs in the system, Lake Mead and Lake Powell, are both under 50% of their capacity. In order for the system to be sustainable, and in preparation for the uncertainty of more bouts of lingering drought and climate change, we must all work together to support a stable and reliable Colorado River system – from the headwaters in the Colorado Rockies to the lettuce fields of Yuma and beyond.

Even with a few wet years, climate impacts are reducing flows on the Colorado River. A recent study by Jonathan Overpeck and Bradley Udall illustrates that warmer temperatures on the river between 2000 and 2014 accounted for a reduction of at least a half-million acre-feet of water a year – the amount needed to support 2 million people. The study concludes that warming temperatures alone could cause Colorado River flows to decline by 30% by midcentury if solutions are not implemented.

Snowpack! Snowpack! Snowpack!!

While water levels in both Lake Mead and Lake Powell will likely rise significantly this summer, it would be unwise to give up on collective and collaborative efforts across the Southwestern US to develop agreements and practices to conserve water across the Colorado River basin. Lake Mead is still over 140 feet below full, and even with a projected rise in Powell to bring it to nearly 66% full by the end of the water year, we still have a long way to go. One good snow year is nice, but the long-term effects of prolonged drought and substantial overuse mandates diligence, effort, and flexibility in how we interact with our delicate yet crucial water supply in the Southwest.

This is a critical year for rivers and clean water. Our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® of 2017 report sounds the alarm.

This year’s report highlights the threat President Trump’s proposed budget cuts pose to rivers and communities nationwide. Number one on this year’s list is the Lower Colorado River, where the communities, economy, and natural resources of the southwestern U.S. will be threatened if the Trump Administration and Congress don’t prioritize and fund innovative water management solutions.

We must protect and restore rivers and clean water for our families, our economy and our future. | Photo: Amy Martin.

“Water is one of the most crucial conservation issues of our time,” said Bob Irvin, President of American Rivers. “The rivers Americans depend on for drinking water, jobs, food and quality of life are under attack from the Trump administration’s rollbacks and proposed budget cuts.”

“Americans must speak up and let their elected officials know that healthy rivers are essential to our families, our communities and our future. We must take care of the rivers that take care of us.” Irvin said.

President Trump has abandoned critical river protections including the Clean Water Rule, leaving small streams and wetlands – sources of drinking water for one in three Americans – vulnerable to harmful development and pollution.

He has also proposed significant budget cuts that would cripple river restoration and protection efforts nationwide, with severe impacts to drinking water supplies, fish and wildlife and recreation.

The Lower Colorado River provides drinking water to 30 million Americans in cities including Phoenix, Los Angeles, San Diego, Las Vegas and Yuma. | Photo: Amy Martin.

These cuts would impact the rivers on this year’s America’s Most Endangered Rivers list. For example:

- Cuts to the Department of the Interior and Department of Agriculture could hamstring efforts to find water management solutions to meet the crisis on the Lower Colorado River.

- Cuts to the Environmental Protection Agency could undermine regulation of pollution from Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations like those on the Neuse-Cape Fear and the Buffalo National River.

- Virtually zeroing out the Land and Water Conservation Fund would eliminate opportunities such as the conservation purchases that have helped protect Washington’s Green River.

- Cuts to the Department of the Interior likely would foreclose any opportunity to adequately fund the proper planning, management, and protection of the neglected Wild and Scenic Rivers System, including the Buffalo National River and Middle Fork Flathead — a sorry state of affairs as the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act approaches its 50th anniversary in 2018.

America’s Most Endangered River, the lower Colorado, provides drinking water for 30 million Americans, irrigates fields that grow 90 percent of the nation’s winter vegetables and slakes the thirst of growing cities including Los Angeles, San Diego, Las Vegas and Phoenix. But the water demands of Arizona, Nevada and California are outstripping supply, the impacts of climate change are becoming acute, and the river is at a breaking point.

If the deficit is not addressed, the Bureau of Reclamation will be forced to cut water deliveries, with severe economic impacts to farms and cities across Arizona, Nevada and California.

Unfortunately, the Trump Administration’s Fiscal Year 2018 Budget proposal threatens to reverse progress made by states, cities and farmers to reduce water consumption across the three states.

American Rivers called on Congress and the Trump Administration to provide support, leadership and financial resources for innovative water savings and transfer projects to conserve and share the region’s water assets.

The Lower Colorado River is the lifeblood of the region’s agricultural industry. | Photo: Amy Martin

The future of the Lower Colorado River is of particular importance to the region’s Latino communities. One-third of the nation’s Latinos live in the Colorado River Basin.

The significance of the river to the faith, livelihood and future of Latino farm-working families is showcased in the new film Milk and Honey, produced by American Rivers and the Hispanic Access Foundation (full film coming Thursday, April 13).

“The Lower Colorado River is an integral part of our heritage and way of life. From serving as the backbone for the agricultural industry to providing a cultural focal point for faith communities, the Lower Colorado River is essential to the livelihood of the Southwest,” said Maite Arce, President and CEO of Hispanic Access Foundation.

“By taking action now we can make strides in ensuring that future generations can continue to benefit from this tremendous resource.”

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/214/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”4″ center=”yes”]Take Action »[/su_button]

It is almost time for American Rivers and partners nationwide to announce America’s Most Endangered Rivers ® of 2017 on April 11. American Rivers releases the report every year to shine a spotlight on urgent threats facing rivers and clean water.

Ten rivers in the following states will be named to the 2017 list: Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Georgia, Michigan, Mississippi, Montana, Nevada, North Carolina, Virginia, Washington and Wisconsin.

This year’s report spotlights the importance of healthy rivers for our drinking water, the food we eat, and the health of our families— and how these values are at risk nationwide.

Today we also have great news about the Chuitna River in Alaska (listed as endangered in 2015). The Chuitna was threatened by a large proposed coal mine. This project would have created the largest strip mine in Alaska and would have buried 13.7 miles of headwater streams. However, on March 31, the company that had applied for permits suspended their permitting efforts. This is a great victory for the health of the Chuitna River and the communities that depend on it for clean water and salmon fisheries.

Recent decisions on last year’s #1 Most Endangered River Apalachicola-Chattahoochee Flint Basin have highlighted the need for continued perseverance in order to cost-effectively and sustainably protect healthy river flows for the environment, for all basin stakeholders, and for future generations. We will be continuing to push for smarter solutions in this important river basin.

Finally, there is still an action that you can take while you wait for this year’s list of endangered rivers. We need your help to ask the U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management to withdraw the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness from mining. We don’t want the progress made toward protecting this special place to lose momentum under the new Administration. Help us tell them to make this a priority!