One of the most tell-tale signs that the management of stormwater was a problem in Atlanta occurred in 2012.

After decades of development, all that was left in this area were parking lots and a deteriorating sewage system. As a result, several homes in the Turner Field communities were flooded by massive amounts of stormwater runoff and sewage.

While Turner Field is currently being redeveloped, residents and community partners could no longer stand on the sidelines. By working together to ensure a community driven development process, the growing concerns of stormwater have gradually been put at ease.

Interstate Pilot Project for Turner Field Communities

Two important initiatives, the feasibility studies of green stormwater infrastructure (GSI) and the Turner Field Neighborhoods Livable Centers Initiative (LCI) plan, helped set forth a plan to aid some of Atlanta’s highways. American Rivers and the LCI team collaborated with the Georgia Department of Transportation (GDOT) to determine a way to aid issues with massive downspout disconnect. With the GDOT funding the green stormwater infrastructure and the construction of the pilot project, the problem was well on its way to being fixed.

One thing remained: Finding another partner group to maintain the installations.

Central Atlanta Progress (CAP) was a no-brainer when it came to finding an enthusiastic partner to join our group and carry out the installations for the GSI pilot project. The CAP upholds a strategic plan that specifically addresses the idea of greening the downtown interstate highways. The next step involved bringing both the GDOT and CAP teams together.

The first meeting between all of the partners was held in early December 2016. Each of the individual team members represented diverse backgrounds and departments, yet all shared a mutual willingness to champion this project. Based off of our feasibility studies, we were able to reach four possible options for the project. By the end of the meeting, we had chosen our construction site: the intersection of I-75/85 and I-20 in downtown Atlanta.

Today, the GSI pilot project is underway and construction is anticipated to begin in the fall of 2017. The landscape architecture firm, Solidago Design Solutions, is now developing design plans for the site that will follow our feasibility assessment recommendations. By using bioretention to capture stormwater, it is likely that the recommendation of 1.8 inches of rainfall will be infiltrated through green stormwater infrastructure.

“Can you hear me?”

For this community in particular, residents often feel misrepresented, as though they cannot voice their opinions. By taking matters into their own hands, residents decided to initiate programs that provide outlets for voices to be heard. Trained citizen advocates represent the desires, concerns, and wishes of the community.

Fortunately, the interstate GSI pilot project is shedding light on the needs of the surrounding community. The project presents the opportunity for the GDOT to evolve their approach to stormwater management systems, while also addressing communal concerns.

An important connection between the flow of people and the flow of water must be an interconnected process. These two parts of a well-oiled machine can improve the holistic design of urban stormwater management, transportation, and sustainability. By implementing a new way of managing stormwater run-off, communities will have the health, quality of life, and access that they deserve.

There is no solitary department, agency, school, organization, or business that can provide the single solution to stormwater management. This is a collective issue that will take a collective effort to make sure that the identity of this community remains intact and is a reflection of its residents.

This interstate GSI pilot project could serve as a model for other State Departments of Transportation in order to address stormwater entering communities, while also incorporating community recommendations and feedback into planning efforts.

At the end of April, American Rivers teamed up with Keurig Green Mountain employees in Suffolk, VA and the Nansemond River Preservation Alliance (NRPA) to install five rain gardens, plant 30 native shrubs, and enhance a 100-foot buffer along Bennett’s Creek, a tributary of the Nansemond River. To talk more about the work we did and the importance of buffers, we’ve asked Elizabeth Taraski of Nansemond River Preservation Alliance to guest blog.

Restoring the impaired waterways of Suffolk, VA requires a sense of community collaboration.

The Nansemond River Preservation Alliance (NRPA), launched in 2010, has been working diligently to educate and encourage citizens to be environmental stewards. One of the key elements at the core of NRPA’s strategy and business plan involves community collaboration, as well as working with like-minded organizations.

The partnership between NRPA and Keurig Green Mountain (Keurig) is known as one of the success stories on the Suffolk waterways. The partnership began in 2012 when Keurig provided grant funding for the NRPA Nansemond Watershed Initiative (NWI): Connecting the Classroom with the Environment, a program for seventh grade students. Over a two-year period, 2,000 students participated in NWI indoor and outdoor hands-on classroom experiences. In 2015, Keurig and NRPA collaborated on a community-based project that emphasized the importance of conservation, and how it protects the waterways.

Three years later, the collaborative partnership continues as Keurig employees came to Bennett’s Creek Park in Suffolk to participate in another community-based site project. This year the project had three components:

- Establishing five rain gardens;

- Planting 30 shrubs along the shoreline;

- Spreading 105 cubic yards of mulch.

In order to be successful, the NRPA worked in collaboration with the Suffolk Parks and Recreation Department to plan and manage the project. The NRPA also provided guidance to employees on how to properly plant shrubs. Collaboration and planning are the key elements to the program’s success. Both Keurig and American Rivers recruited the volunteers, as well as provided the funding for plants, supplies, and refreshments. Most of all, Keurig and American Rivers lifted the momentum for volunteers with plenty of support and enthusiasm.

Immediately after day one of the project, a rain storm drenched the planting site with nearly 1.5 inches of rain. The rain gardens planted earlier in the day were put to the test. NRPA is delighted to report the rain gardens were effective in their mission by reducing storm-water runoff. The riparian buffer is also currently stabilizing as a result of the Keurig’s three years of volunteer work.

Keurig employees have embraced this project as upwards of half of the employees who participated in the past returned to help again. Employees who were new to the program shared that this was their first experience volunteering for an environmental project. It was also the first time that they had the opportunity to plant a native shrub or a tree. Many had never heard of or seen a rain garden. By the end of the day, several were talking about planting their own at home.

The Washington Post recently featured South Carolina’s Congaree National Park in its travel section, boasting of its towering old growth bottomland hardwood trees, sinuous rivers and paddle trails, and rich cultural history.

American Rivers has worked to protect and restore the Congaree River and the National Park for nearly a decade. Our first blue trail projects are on the Congaree and Wateree Rivers, which converge at Congaree National Park in near Columbia, South Carolina.

The Congaree River Blue Trail is the first water trail designated a National Recreation Trail in South Carolina by the Department of Interior. American Rivers has been instrumental in assuring enhanced stream flows to support boating and habitat for fish and wildlife as part of a new federal licensing for upstream dams.

The Washington Post article is right. There’s much to explore along the Congaree River. Learn more about the Congaree River and plan your own adventure down the river.

In the Eagle Lake watershed – located east of Mount Lassen National Park – a myriad of local, state, and federal partners are working to restore some of the largest meadow systems in California and recover one of the West’s most iconic native trout. The wettest winter on record gives us a look at what these restored meadows might soon offer as new habitat for the imperiled Eagle Lake rainbow trout.

This is the intersection of Little Harvey Creek and Pine Creek, aptly named ‘Confluence meadow’. Under normal circumstances, this meadow is dry and doesn’t support a healthy and diverse aquatic community of species. Like many of the meadows in the Pine Creek watershed, it is dewatered by decades of channel incision due to a variety of legacy land uses in the watershed. That unnaturally-deep and straight channel on the left of the photo above acts like an open cut, draining groundwater from the meadow, and leaving the great-looking habitat on the right of the photograph high and dry. Restoration work at this site proposes to abandon the left channel so that Pine Creek will flow through the meadow floodplain like it once did naturally, providing surface water longer into the hot summer months. Flood waters will soak deep into the meadow, be stored as groundwater, and recharge Pine Creek with cold, clean water to support, among other species, naturally spawning Eagle Lake rainbow trout.

The Eagle Lake rainbow trout is an endemic, at-risk California native trout species that has not successfully spawned in the Pine Creek watershed in considerable numbers since the 1950’s, largely due to poor watershed condition, a man made fish barrier, and inadequate flows. A fish ladder was installed over the barrier in 2012, but low flows during the drought and poor habitat condition have prevented spawning in recent years. According to the US Fish and Wildlife Service’s conservation strategy, meadow restoration is an integral component to recovering the species.

Thanks to the record winter, we get a glimpse of what a working floodplain and functional meadow will once again look like. Solving complex watershed issues takes time, vision, and a strong and broad partnership. Partners working towards long-term goals to recover Eagle Lake rainbow trout include the US Forest Service, Eagle Lake Guardians, California Department of Fish and Wildlife, Susanville Indian Rancheria, UC Davis, the Honey Lake Resource Conservation District, local ranchers and anglers, Trout Unlimited, and American Rivers.

[metaslider id=38053]

By David Lass and Luke Hunt

Dave Lass is California Field Director for Trout Unlimited. Luke Hunt is Director of Headwaters Conservation for American Rivers.

Photos courtesy Trout Unlimited, Drone Productions, and Todd Sloat

This guest post from Shelly Covert is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Bear River.

“The Bear River is an important piece of Nisenan culture both today and in our long, rich history. The Gold Rush era completely changed our waterways, and we cherish this last wild and free-flowing stretch of water. To flood this landscape is to further erase the Nisenan culture from the land; we can’t face that again.”

– Shelly Covert, Nevada City Rancheria Nisenan Tribe

Nem Seyo, Kumim Seyo, Tu’im Seyo— the Nisenan words for what we call today, the Bear River.

This place is the ancestral home of the Nisenan (or Nishenam) people. It serves as a territorial divide for three different Nisenan Tribal entities— the group who is south of the Bear currently known as the United Auburn Indian Community, the group who are east of the Bear modernly known as the Colfax-Todd Valley Consolidated Tribe and the Nisenan who are north of the Bear known as the Nevada City Rancheria.

These lands and people are part of Nisenan tribal heritage, a heritage that can be proven back before the Gold Rush and points of non-native contact. Inundation of this important landscape by the proposed Centennial Dam project would have a significant, negative impact on Native American cultural, spiritual, and historical resources.

The Nisenan people were at ground zero of the California Gold Rush. Our numbers were so significantly reduced that today very few of us remain. I have read that the Nisenan Indians of this area are extinct, but in reality we are still here and many of our people still use this wild stretch of threatened river for cultural and ceremonial activities today. This proposed dam would flood historic, cultural and sacred sites used by the indigenous people before, during, and after contact.

Recently, several Nisenan representatives came together at the Bear River Campground, one of the landmarks that would be underwater if this dam is built, to share with and educate the public about who we are and our connection to the land. We engaged in dialog about our culture, our families, our history, and our desires to see this project halted. We also convened a circle discussion to talk about the dangers of cultural appropriation and tips on how to be a good ally to native movements and native people.

The Standing Rock movement has spurred people into action and they are passionate and adamant about standing in solidarity with the Nisenan people. The Nisenan representatives felt that it was a very successful weekend. The public participants were open and eager to engage with the indigenous people whose cultural landscape is under threat from the proposed Centennial Dam. The guests also took time to get to know and experience the wildness of this river.

While at the campground, I took time to reflect on the past. I thought about the stories I learned from my Elders. Many of these stories center around loss of land, loss of people, and loss of culture. I thought about the burial grounds that would be destroyed if this proposed dam were to be built. I thought about the two dams that are already damming this river, Rollins and Combie. How many dams can one stretch of river endure? How much more culture can the Nisenan endure to lose? It’s like stretching a rubber band really tight— I believe we, like the Bear River, may be stretched so far, another tug might be the last. When will enough be enough?

These ancestral waters are sacred to my Tribe. Centennial Dam would flood Nisenan cultural and sacred sites and further erase our people’s heritage. Therefore, we are pleading for alternatives to this project.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/716/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

Shelly Covert is the Spokesperson for the Nevada City Rancheria Nisenan Tribe. She sits on the Tribal Council and is community outreach liaison for her Tribal membership. She is also the Executive Director of the newly founded non-profit, the California Heritage: Indigenous Research Project, whose mission is to preserve, protect and perpetuate the Nisenan Culture.

Saturday, May 27th marks the second anniversary for the Clean Water Rule advanced by the Obama Administration which took a vital step towards safeguarding our nation’s clean water supply. Unfortunately, right now the Trump Administration is working to repeal the Clean Water Rule, while also proposing massive cuts to the Environmental Protection Agency and other clean water safeguards in the federal budget. This is an unprecedented attack on our country’s rivers and your clean drinking water.

The Clean Water Rule provides protection for the small streams and wetlands that contribute to the drinking water sources of one in three Americans. People need clean water to drink and businesses, like the beverage and outdoor recreation industries, rely on clean water to be profitable.

Small streams and wetlands also protect communities from flooding. Climate change is exacerbating our nation’s susceptibility to disastrous flooding events and these small streams, wetlands, and floodplains help to store floodwaters before they reach communities and cause destruction. They also recharge groundwater supplies, provide space for recreation, absorb pollutants, and provide critical habitat to many species and more.

The Clean Water Rule is based on more than 1200 publications of peer-reviewed science and was reviewed by the EPA’s Science Advisory Board. It protects small streams and wetlands because science tells us that small streams and wetlands are connected to and have a strong influence on the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of downstream waterways such as rivers.

For all of these reasons, we need to be doing more, not less, to safeguard our rivers and water supplies. But President Trump is going in the opposite direction, proposing massive budget cuts to clean water and river restoration efforts. His budget proposal includes deep cuts to the Environmental Protection Agency, proposing to cut the agency by almost one third by slashing funding for vital environmental initiatives including EPA’s enforcement and compliance program for bedrock environmental laws. The budget virtually eliminates funding for regional restoration efforts, including the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative and the Chesapeake Bay Program, each of which provide resources to states and communities trying to restore and protect the rivers that flow into these iconic waterways.

The Trump Administration’s budget proposal and its work to repeal the Clean Water Rule in order to better serve corporate interests, put the health and well-being of Americans at risk.

In the words of American Rivers President Bob Irvin, “We need to take care of the rivers that take care of us.”

Americans must call their members of Congress and speak up against the administration’s attacks on our clean water. American Rivers will continue to fight to safeguard the rivers and streams that connect us all, and to protect clean drinking water for American families and future generations.

Bristol Bay. Pebble Mine.

I can’t believe we’re here again.

I suppose I should back up. We haven’t talked about Alaska’s Bristol Bay in a while because… well… things were actually going okay. If you have a memory like a steel trap, you might remember that American Rivers included Bristol Bay rivers (i.e., the Kvichack and Nushagak rivers and their tributaries) among America’s Most Endangered Rivers® in 2011. The rivers, and the world’s largest sockeye salmon run, were threatened by the Pebble Mine – a mine of staggering scale that would cause irreversible damage to clean water, salmon, and an entire way of life.

Then in 2014, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) said that the Pebble Mine would cause irreversible and unacceptable damage to Bristol Bay and its associated ecosystem that supports treasured salmon. More than one million people submitted comments asking for strong protections for Bristol Bay. We’re not talking about a couple of people who don’t want a mine in their backyard. Hundreds of thousands of people across the country said NO. This place is too special to contaminate and bury.

EPA agreed. They said no.

Fast forward to 2017. New Administration. New EPA Administrator, Scott Pruitt. Last week the EPA reached a settlement agreement with the Pebble Limited Partnership, a subsidiary of Northern Dynasty Minerals Ltd., which reverses EPA’s earlier decision that the project would be too detrimental to the salmon fishery.

How could a “too harmful” determination that was based on science suddenly become okay? Never mind about sustainable fish populations. Never mind about the economic livelihood of local residents. Never mind about indigenous rights. Never mind.

Bristol Bay and its associated ecosystem are home to some of the most treasured salmon fisheries. | Bob Waldrop

So… what happens next? Despite some calls for dismantling environmental regulations in Washington, DC, we fortunately do still have regulatory hurdles in place that will take time to surmount. Projects like this do not get permitted overnight. Shepherding this massive project through the permitting process will also be expensive (Pebble estimates this will cost $150 million). Alaskans are planning to stand up for themselves as well. They passed a ballot measure last year that requires any large-scale mine in the Bristol Bay region be approved first by the state legislature. The state of Alaska owns the lands where the mine would be developed.

This is by no means a done deal. What this means is that Pebble Mine is back on the radar. It could end up back on the endangered rivers list. Only time will tell.

Let’s be clear about one thing – President Trump’s April 26 executive order in which he directed Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke to review all national monuments of more than 100,000 acres created since 1996 is not a routine review meant to improve management of some of America’s most treasured public lands. It is a frontal assault on the Antiquities Act and a precursor to eroding protections for at least some of the more controversial monuments that were proclaimed by both Democratic and Republican presidents over the past two decades.

President Trump’s executive order was issued at the behest of members of Utah’s congressional delegation, who went apoplectic after President Obama proclaimed the 1.35 million acre Bears Ears National Monument in southeast Utah last December. But the order could affect as many as 27 national monuments from Maine to the South Pacific.

Here in Montana where I live, the executive order threatens to weaken protections for the Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument, proclaimed by President Bill Clinton on January 17, 2001. This spectacular monument encompasses 378,000 acres of federal public lands along and adjacent to the 149-mile-long Wild and Scenic reach of the Upper Missouri River, one of just four Wild and Scenic Rivers in Montana. It was this landscape that most inspired the great western artist, Charles M. Russell, for whom a nearby national wildlife refuge is named.

In the Upper Missouri River Breaks, Americans can get a rare glimpse of what the Northern Great Plains looked like when Meriwether Lewis and William Clark passed through on their way to the Pacific Ocean in 1805. Here, the Missouri River flows past dazzling white sandstone cliffs, rugged badlands, and century-old cottonwood groves, and the stars in the night sky shine so bright it seems you can reach out and touch them. My favorite way to enjoy the monument is by taking a five-day canoe trip through the White Cliffs section, where one can fish, hunt, hike, and search for Native American pictographs in hidden side canyons.

As wild and remote as this landscape is, the designation of the Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument allowed historic activities such as livestock grazing, off-trail motorized use, and flying small planes into remote airstrips to continue, even though many visitors would like to see them phased out to restore the area to a more pristine condition. About 10,000 cattle graze within the monument, which takes a toll on riparian vegetation such as cottonwood seedlings that grow on sand and gravel bars deposited by spring floods.

Americans are incredibly fortunate that President Theodore Roosevelt had the foresight to come up with the idea for the Antiquities Act, which allows presidents to declare national monuments to preserve some of our country’s most magnificent natural and cultural treasures without having to go through Congress. He recognized not only how special our public lands are to the American identity, but also how dysfunctional Congress can be when it comes to setting aside these places.

Please help us protect the Upper Missouri River Breaks, Bears Ears, and other national monuments from the Trump administration’s unprecedented attack on the Antiquities Act and our public lands legacy.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/804/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

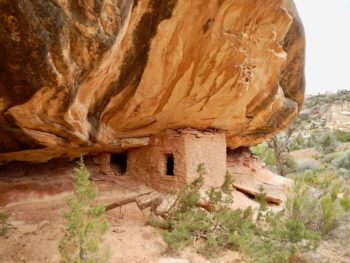

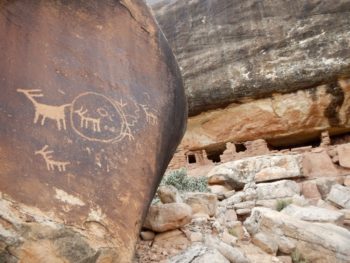

Stars sparkle overhead with a clarity that only comes far from electric lights. Tree frogs hum from the canyon below, coyotes howl on the mesa above. The soft “hoot, hoot-hoot” of a Great Horned owl echoes from above an alcove nearby. This alcove also happens to contain an Ancestral Puebloen granary which was made from stacked stones, clay mortar, and juniper beams over 700 years ago, still containing bits of corn and potsherds left behind by its previous owners.

One week before Department of Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke visited Bears Ears National Monument on order from President Trump’s executive to review national monuments designated since 1996 under the Antiquities Act, I found myself camped high above Grand Gulch, a Wild and Scenic eligible stream flowing off Cedar Mesa in Southern Utah. The wildness and history of Grand Gulch, located within Bears Ears National monument, exemplifies what is so special about this region.

An Important Place

This is a landscape that was thousands of years in the making. Formed by a shallow, inland sea, the sedimentary rocks that underlay the region team with fossils and dinosaur tracks, and are marked by the crossbedding of prehistoric dunes. Canyon streams flow from high plateaus that brim with Ponderosa pine, aspen, deer, elk, coyotes and black bears. They cross Pinon-Juniper forests and finally descend through steep-walled canyons dotted with alcoves and natural arches on their way to either the Colorado River or San Juan River. Many have year-round water in them and are so special that they are being considered for designation under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. They are the life blood of this parched, desert ecosystem.

In canyon alcoves, the observant traveler can view cliff houses, writings, and artifacts left behind by the ancient people that lived there 700-1000 years ago. All it takes is a free permit from BLM’s Kane Gulch Ranger Station and a short training so that one knows how not to harm this fragile landscape; How to dispose of human waste in a “cat hole” at least 100 feet from precious water sources or carried out in a special bag. How to travel and camp on durable surfaces, avoiding cryptobiotic soil crusts, and sensitive riparian areas. How to respect archeological sites by not climbing in or on granaries or cliff dwellings, not touching pictographs and petroglyphs, and by leaving any artifacts that you find.

For those of us who love the canyon country it is difficult to promote visiting them – both the ecosystems and the artifacts are fragile, and cannot handle users that are careless. This special area also needs to be known and loved in order to be protected.

National Monuments Need to be Maintained

Few places in our country are worthier of such protections. Working out the mechanics of these protections took diverse groups of people years of meetings and discussions. It is ironic that we are now faced with a short comment period while the current administration decides whether or not to shrink or rescind dozens of beloved national monuments, including Bears Ears. Competing interests want to allow more oil, gas and coal development in this unique landscape, risking the pollution of rivers, destruction of cultural history, and radically changing the roadless canyon country that remains intact.

Eliminating or damaging Bears Ears and Utah’s other national monuments also risks harming the state’s $12 billion outdoor recreation economy, which provides 122,000 direct jobs and $856 million in state and local tax revenue. Nationwide, our national monument system is a key component of our public lands that support the $887 billion U.S. outdoor recreation economy, providing Americans with 7.6 million jobs, not to mention places to seek solace and connect with both natural and human history.

Help Us Protect Bears Ears

We need your help to protect Bears Ears and ALL of our national monuments. These areas are our country’s heritage, and they need your voice. Submit a letter of support for Bears Ears National Monument before May 26.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/804/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

This post is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Bear River.

Northern California’s Bear River is threatened by the proposed Centennial Dam, which would inundate six miles of the last publicly accessible free flowing stretches of the river.

Over the next few weeks, we’ll introduce you to a series of posts that explore different aspects of the Bear River, #2 on the list of America’s Most Endangered Rivers® of 2017.

Welcome to the Bear River

The Bear sits in an often overlooked watershed, nestled in California’s Sierra Nevada Mountains, flowing 73 miles from rocky crags and conifer forests to the oak woodlands, open grasslands, pastures, and fields of the Central Valley.

When European-Americans first came to the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, everything changed; hillsides were washed away in the search for gold, and rivers were forever changed. The Bear was in the heart of that rush. Mining gave way to agriculture and, later, to residential development in the watershed.

The resulting water infrastructure leaves the Bear River impounded behind a series of dams over much of its course. Despite the history of heavy-handed manipulation (and perhaps even more so because of it), the remaining stretches of free-flowing water on the Bear River are a lifeline for local communities and wildlife.

The Bear River supports recreation, cultural use and rare habitat. Locals and visitors enjoy hiking, birdwatching, camping, angling, gold panning, rafting, and kayaking on the Bear’s four-mile class II whitewater run. The river is also home to numerous historic sites, including Native American Nisenan village and burial sites. Today, the mature mixed conifer and oak woodlands along the river are still used by Nisenan for plant collection and ceremonial purposes.

The river’s woodlands are an incredibly diverse ecosystem that provides habitat for an abundance of sensitive species, including California black rail, bald eagle, foothill yellow-legged frog, ringtail cat, and big-eared bat. The lower reaches of the river support a number of iconic fish species, including Chinook salmon, Central Valley steelhead, and green and white sturgeon.

You can find a more detailed account of the river and its history here.

What’s at stake?

The 275 foot tall Centennial Dam would flood the most popular river access points for recreation, along with dozens of Nisenan cultural sites and over a thousand acres of oak woodlands and riparian forest. It would turn six miles of flowing river into yet another reservoir in a nearly unbroken 17 mile chain of reservoirs in the middle reaches of the Bear.

The dam proponents, Nevada Irrigation District (NID), claim that they need to build the dam to overcome the challenges posed by climate change, and to meet growing water demands in the future. However, NID has not demonstrated that it is following best practices for water conservation and efficiency, or that the water to fill this new reservoir will be available in the Bear River watershed under predicted future climate conditions.

Further, NID’s own cost estimates for the dam have risen from $160 million to $500 million (a common occurrence with reservoir projects elsewhere in the country). Local community members have raised serious concerns that the anticipated costs of the dam would undermine needed repairs and more effective climate change management strategies, such as water use efficiency and optimizing existing systems.

What can be done?

Across the country, communities have been rising to water supply challenges like drought, climate change, and growing populations with innovative water conservation and new approaches to water management. In many cases, they have been able to save considerable amounts of money compared to traditional water supply projects like new dams.

NID should work with the community and river advocates to pursue common-sense water conservation measures and alternatives that promote resilience to climate change without destroying invaluable natural, cultural, and recreational resources. A new dam should be the last alternative considered, not the first.

Fortunately, Centennial Dam must pass through many hurdles before construction, and faces multiple turning points in the next year from state and federal decision makers. It is imperative that organizations and individuals maintain pressure on NID and other key decision makers to reevaluate the need for this new dam.

Right now, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) is conducting federal environmental review for the project, and has the authority to deny permits to build the dam. Join us in asking the USACE to deny permits for the dam in favor of alternative actions that would improve water security in light of a changing climate, while preserving and enhancing the rich natural, social, and cultural resources of the Bear River.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/716/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

The Department of the Interior is considering possible reducing or eliminating protections for millions of acres of public land within 27 National Monuments established since 1996. This “review” has been directed under an Executive Order issued last month by President Trump. Despite promises of an open process and an opportunity for public comment, the process appears to be nothing more than window dressing for an unprecedented rollback of conservation of our public lands. The pomp and circumstance surrounding this review is simply the prelude to an undoing of more than one hundred years of conserving our nation’s special places by every President since Teddy Roosevelt.

Last week, Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke arrived in Utah to kick off the review with a tour of the Bears Ears National Monument the most immediately threatened by Trump’s order. Bears Ears, in Southeast Utah, is considered sacred by many tribes and its designation was achieved after years of advocacy by the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition of Hopi, Navajo, Ute Indian Tribe, Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, and Zuni Pueblo. The area is rich in important cultural history, home to more than 100,000 Native American archaeological and cultural sites, and includes the cherished San Juan River.

Given his statement that “sovereignty has to mean something,” we would encourage Secretary Zinke to listen more extensively than possible in a one-hour meeting with the Coalition and the governments its represents, as well as to appreciate the 13,000 years of history manifested in the tribal resolutions supporting protection.

At a rally in Salt Lake City over 1,000 supporters of Bears Ears made their own statement at a rally on the steps of the Utah state capital. Among the speakers was the Navajo Nation representative on the Bears Ears Commission and Oljato Chapter President James Adakai. President Adakai stated that his umbilical cord and those of his ancestors are ceremonially buried in Bears Ears, evidence of the sacred connection he and his people enjoy with this special area entrusted to the American people.

In addition to Bears Ears, the Trump National Monument target list includes a myriad of incredible landscapes and rivers cherished by other Americans that are now under threat. A few of the river specific monuments in addition to the Bears Ears are:

[metaslider id=37901]

Hanford Reach National Monument, Washington, protected in 2000

- The 51 mile-long Hanford Reach is the last free-flowing stretch of the Columbia River and is home to the largest salmon in the Columbia Basin.

- Culturally, the Reach is significant to a number of Indian nations, including the Umatilla, Yakama, Nez Perce, and Wanapum tribes.

Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument, Montana, protected in 2001

- Supports a spectacular array of species from pronghorn, golden eagle, yellow headed blackbird, sage grouse, bighorn sheep, and the endangered pallid sturgeon.

- Rich in Native American cultural significance the Breaks is largely unchanged Meriwether Lewis and William Clark traveled through the Breaks in 1805.

- The Missouri River is also protected as a Wild and Scenic River, offering outstanding recreation opportunities and fish and wildlife habitat.

Rio Grande Del Norte National Monument, New Mexico, protected in 2013

- The Rio Grande is protected as a Wild and Scenic River and is popular for rafting and camping.

- The river is significant to Native American tribes including the Tesuque Pueblo (one family’s connection to the river is highlighted in the new American Rivers film, Avanyu: https://vimeo.com/197904986 )

Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument, Oregon, protected in 2000 and expanded in 2017

- The monument safeguards pristine clean water supplies and rare Redband Trout habitat.

- Cascade-Siskiyou is the first U.S. national monument set aside solely for the preservation of biodiversity.

San Gabriel Mountains National Monument, California, protected in 2014

- More than 15 million people live within 90 minutes of the San Gabriel Mountains, which provides 70 percent of the open space for Angeleños and 30 percent of their drinking water.

Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument, Maine, protected in 2017

- Described by Henry David Thoreau in his journals, the Penobscot and Seboies Rivers in the monument provide habitat for moose, black bear, many species of fish, and a rich biodiversity of other flora and fauna.

- The Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument is a New England’s newest recreational gem, providing opportunities to fish, hunt, canoe, snowmobile, cross-country ski, snowshoe, hike, and otherwise enjoy the beautiful “continuous of the forest,” to use Thoreau’s words.

No President has ever reviewed or reversed a previously established National Monument and we should not start now.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/781/petition/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

National Monuments are selected by the President from tracts of existing public lands to preserve landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and objects of scientific interest. The President has this power under the Antiquities Act, which Congress passed and President Teddy Roosevelt signed in 1906. Congress delegated the power to further protect parts of public lands because even then, it could be difficult to move preservation bills to the President’s desk.

Almost every President since Teddy Roosevelt has used this Act to safeguard places of incredible natural beauty, historical significance, or cultural/spiritual value. Many monuments restrict drilling, mining, and other activities that can damage sources of drinking water or essential habitat. Before the President uses the Act (makes a “declaration”), there is an extensive review process with high levels of stakeholder engagement.

Secretary Zinke, at President Trump’s instruction, is “reviewing” National Monuments in what can only be a prelude to a monumental selloff. Under consideration are all monuments designated since 1996 that are over 100,000 acres or where the “Secretary determines that the designation or expansion was made without adequate public outreach and coordination with relevant stakeholders.” Under threat are 22 National Monuments in 10 states.

It is an unprecedented move by both a President and a Secretary of the Interior who had been adamant that they would keep public lands public. While they have failed to legislatively sell off the public estate, they believe they can illegally use the Antiquities Act to allow one President to undeclared a National Monument . Only Congress has the power to revoke a Monument designation and the Department of the Interior’s top lawyer has previously stated Presidents cannot undeclare Monuments.

Located at the crossroads of the Cascade, Klamath, and Siskiyou mountain ranges, scientists have long recognized the outstanding ecological values of the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument. | Bob Wick, BLM

Extremists and opportunists, mostly in the West, want increased resource extraction on and private ownership of federally owned lands. While multi-use public lands, particularly those operated by the Bureau of Land Management and the Forest Service, are an essential part of the federal estate, the value of maintaining places of historical, cultural, and scientific significance cannot be discounted. The designation of a National Monument does not prevent the land from being used for multiple purposes, it simply allows the President to more narrowly tailor its uses to protect the important national values the tracts possess.

Caught in this dragnet is the Katahdin Woods Monument in Maine, composed of land donated by a private landowner and endowed so generations of Americans can continue to enjoy the land, as well as the Cascade-Siskiyou Monument in Oregon, which was preserved for its incredible biodiversity and is a popular outdoor recreation destination and source of drinking water.

Don’t be fooled. President Trump and Secretary Zinke aren’t trying to right-size Monuments, they’re trying to down-size your public lands and special places. Don’t let them.

Take action today to protect our monuments and public lands.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/781/petition/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]