National Monuments are selected by the President from tracts of existing public lands to preserve landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and objects of scientific interest. The President has this power under the Antiquities Act, which Congress passed and President Teddy Roosevelt signed in 1906. Congress delegated the power to further protect parts of public lands because even then, it could be difficult to move preservation bills to the President’s desk.

But, unfortunately, President Trump has issued an executive order calling for a review of National Monuments designated under the Antiquities Act. Following the order, The Department of the Interior announced a public comment period for 27 specific National Monuments designated in the last 21 years. This review is unprecedented and unnecessary, and we encourage you to speak up in defense of these important public lands. The deadline to submit a comment is Monday, July 10th.

The Hanford Reach National Monument in Mattawa, WA, one of the monuments under review, includes the last free-flowing stretch of the 1,243-mile Columbia River above Bonneville Dam and is home to the largest run of Chinook salmon in the lower 48. One of the highlights of the Monument, the beautiful and iconic White Bluffs, was formed millions of years ago and contains a wealth of fossils, including mastodons, camels, zebras and rhinoceros. In addition, the area has a long and rich history of Native American habitation and use and is culturally significant to tribes throughout the region. More than 150 registered archaeological sites are found within the monument’s boundaries.

The Hanford Reach is also a popular destination for many types of recreation and exploration. Public use of the monument has grown from less than 20,000 visitors at the time of designation to 43,000 annual visitors today. It is a local and regional destination for waterfowl hunters and salmon, steelhead, sturgeon, and bass anglers. It has grown in popularity as a destination for kayaking and canoeing. The Hanford Reach National Monument Vision Statement states that the “monument is a natural gathering place to learn, to experience and celebrate cultures, where stories are protected and passed on.” Recreational experiences provide important learning opportunities to continue to tell these stories from one generation to the next.

In June 2000, President Clinton created the 195,000 acre Hanford Reach National Monument to preserve its unique natural, cultural, historical, scientific, and educational asset for all Americans, a tailor-made case for the Antiquities Act. The designation took place after over ten years of studies, reviews and community input from federal, state and local agencies; local organizations representing a variety of interests including American Rivers; and private landowners living along the Reach. President Trump’s Executive Order and the Department of Interior’s review of the Hanford Reach National Monument is unnecessary and a waste of tax-payer money.

We urge you to submit a comment in favor of keeping the Hanford Reach National Monument as it is. Sample text is provided below but please note that unique comments in your own language will have a greater impact than copying and pasting the below bullet points. We encourage you to personalize your comments.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/1234/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action before July 10th »[/su_button]

Here are a few important points to touch on in your comment, if you’d like guidance:

- Reference your own experience at the Hanford Reach National Monument. Comments that can speak to the “objects of scientific interest” that define the Monument including the shrub-steppe ecosystem with a diversity of plant and animal species, geology of the White Bluffs, bird habitat, spawning habitat for fall Chinook salmon, or Hanford Dune Field are especially helpful.

- Reference the importance of outdoor recreation in protecting the Hanford Reach National Monument by providing experiences that promote a culture of stewardship for this place. The 51-mile Hanford Reach is the longest wild and free-flowing section that remains of the entire 1,234-mile Columbia River. It is a popular destination for paddlesports enthusiasts, anglers, botanists, bird and wildlife watchers, and more.

- If you have a personal perspective or participated in the public process that included proposed legislation for wild and scenic designation of this reach and ultimately led to National Monument designation, please include in your comments.

- Urge the Department of Interior to protect the integrity of the Antiquities Act, which has been used by Presidents of both parties for over 100 years to protect some of the most amazing cultural and ecological sites that exist in the country.

Ultra-marathon runner and biologist Keith “Wildman” Hanson is gearing up for his greatest journey yet – a 3 day, 300 mile run across South Carolina.

As a biologist and conservationist, Hanson is keenly aware of the threats that face America’s rivers and decided the best way he could bring attention to this issue was to do something that seems impossible to many. In November, the “Wildman” will tackle this great adventure.

Beginning in Upstate South Carolina, near the Saluda River and ending by the Stono River near Folly Beach, Hanson is going to run alongside some of South Carolina’s most iconic rivers; rivers that need our protection. From the mountains to the sea, Hanson’s goal is to complete this 300-mile journey across the Palmetto State in three days. He will test his body and mind to a degree he never has before, but that is what makes him the “Wildman”.

We recently caught up with Hanson to learn more about his connection to rivers. Read on for our interview with Hanson.

Why are rivers important to you?

KH: Rivers are important to me for a number of reasons.

First, there is just something that is so mesmerizing, so alluring, and intoxicating about beautiful, clean flowing water. It is primitive in a way, almost animalistic, but there is something deep within me that is moved when I see or when I am in flowing water. Rivers can literally and figuratively wash away the grime and stress of a hard day. Rivers always leave me feeling recharged and refreshed.

Rivers are important to me as a natural resource. Rivers are a vital part of the landscape; in fact, rivers play a major role in forming the landscape. Rivers are also critically important to nearly every ecosystem and are essential to human cultures and economies. It is nearly impossible to overstate the importance of rivers as a natural resource, especially as most of the population gets their drinking water from rivers.

Personally, rivers are especially important to me as a natural resource because of their function as a fish habitat and as a source of drinking water. Let us be quite clear, without rivers, we would not have such amazing craft beer!

Lastly, rivers are important to me recreationally. This is obviously intertwined with my last answer as it relates to rivers as a natural resource. Rivers provide a remarkably wide range of opportunities for consumptive and non-consumptive recreational uses. I love rivers for kayaking, fishing, birding, swimming, floating, looking for herps (reptiles and amphibians), and of course, running! Running next to, over, or through rivers really brings me great joy and makes the miles just flow by!

Whether you realize it or not, rivers are important to everyone. As American Rivers so eloquently states: Rivers connect us.

Is there a particular river that is special to you?

KH: I would have to say that there are two rivers that are especially important to me. The first is the Rocky River up in northeast Ohio where I grew up. The Rocky River is special to me because it is where I came to love rivers, wildlife, and nature in general. When I was growing up, my family would go on hikes and bike rides all along the river, constantly exploring the many miles of meanders. Spending so much time exploring the river, being immersed in nature is likely what propelled me to become a biologist and is the reason I am so passionate about research and conservation. Additionally, growing up in northeast Ohio, rivers are a special part of the cultural identity. This likely stems from the presence of the Cuyahoga River, which caught fire many times during the 20th century, most notably in 1969.

The second river that is special to me is the Cooper River in coastal South Carolina. The Cooper River is likely most famous for the “Cooper River” bridge (real name: Arthur Ravenel Jr. Bridge), which is a beautiful cable-stayed bridge that resembles a sailboat. The bridge is also well known because of the Cooper River Bridge Run, a 10-km footrace that takes runners across the bridge. For me, the Cooper River was really the first river in the southeast where I spent a lot of time when I moved down to Charleston in 2009. Boating, wakeboarding, birding, and just doing some cruising were some of my favorite things to do on the Cooper River my first few years in Charleston. Following graduate school, I started to do more research related to the river and found out how truly special, but also how modified, the river is. Since then, I’ve always had a special interest in the Cooper River. Recently, I was able to accompany the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources out to sample for endangered shortnose sturgeon (Acipenser brevirostrum) in the river. This sampling trip was an amazing experience and reaffirmed my passion for the river.

What do you hope to accomplish with this run?

KH: Primarily I hope to raise awareness and funds for American Rivers and the amazing conservation work they are doing every day. Everything else is secondary to that. However, because this is an endurance running adventure, my goal is to complete the fastest upstate-to-coastal crossing of South Carolina on foot. Using an endurance adventure like this represents a unique opportunity to reach out and inspire people about the importance of rivers.

What is the hardest thing about a long-distance run like this?

KH: It is difficult to pinpoint the hardest thing about a long-distance run like this, but I would have to say that sleep deprivation will likely be the biggest challenge. I am planning to sleep for short periods during the run (maybe 2-3 hours every 24 hours), but if I get behind schedule in time and/or mileage, sleep will be the first thing that is cutback. Aside from that, ultramarathon running in general presents a number of challenges. Something like a little pain or a blister can turn into a nightmare during a 300-mile run, whereas during a normal training day, it may not be an issue at all. Keeping up with hydration and calorie intake will be a significant challenge as well.

Describe a typical day of training.

KH: Right now, a typical day of training is “light,” as I have not ramped up the mileage. I am trying to get about 60 miles of running in per week, with that running evenly distributed among days. I am also doing a lot of strength training and mobility work. I would say that a typical day looks like this: After work, I like to do some light foam rolling and hip mobility work before I do any running. That lasts for about 15 minutes. Then I will do a dynamic warmup for about 15 more minutes. This involves jumping jacks, lunges, light jogging, other movements (no static stretching). Then I will do something like a focused strength workout (e.g., squats, lunges, single-leg squats, kettle bell swings) then take off on a run of anywhere from 8 to 12 miles. Following any run, I do some targeted stretching for a few minutes. Later at night, after dinner, shower, etc. I also do more mobility work, which involves a lot of foam rolling.

Tell us your favorite river story.

KH: I think one of my favorite river stories is from back home in Northeast Ohio. Many years ago, I was in the Rocky River with my family, just splashing around in a shallow section characterized by exposed bedrock with some larger stones. We were all flipping rocks (placing them back in their original location after flipping, of course) looking for crayfish and any other little critters. I was flipping some medium-sized stones and was not having any luck. So, as a kid, my attention started to wane a bit. Anyway, after a while of this, I thought I saw a little stick jammed underneath one of the stones, so I thought it might be a good place for some crayfish. As I lifted the rock, a ton of crayfish came shooting out! I quickly realized that stick was not actually a stick! This small brownish/grey snake catapulted itself right out from under the rock and through my legs before I really knew what happened. Without thinking, I took off running full speed after it. Luckily, I was able to run on the bedrock without slipping, but I could see that I was running out of real estate and there was a deep pool section just ahead. I was directly behind the snake as it made it to the deep pool section. At that point, I just went for it and dove – fully laid out like a major-league outfielder – directly into the deep pool section where I definitely could NOT touch the bottom. Treading water and fully clothed, with water running down my face, I held up the Queen Snake (Regina septemvittata) and yelled over, “I got it!” I swam my way back to the shallow bedrock and we all looked at the snake and its beautiful brown/grey dorsum with yellow/cream stripes running down its sides. After a few minutes of taking turns holding it, we let the snake go back into the water, hopefully unharmed, but certainly annoyed and probably late for dinner. Later, I found the habitat/ecology information for the snake: “…often prevalent where rocks are present and an abundance of crayfish.” Seemed like an accurate description to me.

How did you learn about American Rivers?

KH: I learned about American Rivers through their dam removal and restoration work in the Southeast. As the nation’s leading river conservation group, they are widely known in conservation circles. Specifically, I think the Lassiter Mill Dam removal on the Uwharrie River in North Carolina was a focal point for me personally recognizing American Rivers’ work in the region.

About Keith “Wildman” Hanson

Although Keith “Wildman” Hanson is widely known as an ultramarathon runner, he is first and foremost a dedicated biologist and conservationist. Keith has long used his ability to run impossible distances as an avenue to promote and bring awareness to causes he wholeheartedly believes in.

“My goal is to use this personal endurance challenge to raise funds and bring awareness to the importance of rivers,” Keith said. “American Rivers is a great organization and I am thrilled to team up with them and bring awareness to the great work they do every day. Rivers are vital to our ecosystems and economies, and my hope is to shine a light on the fact that many rivers are in deep trouble right now. As a biologist and environmental scientist, I have spent years studying rivers and how they directly influence human health and prosperity. I believe this adventure has the opportunity to have a positive impact for rivers and the communities that rely on them.”

Keith graduated from Baldwin-Wallace University in 2008 with a B.S. in biology and environmental studies. He earned his M.S. in environmental studies from College of Charleston in 2012. He currently works as a contract environmental scientist for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) where he focuses on the conservation of freshwater, estuarine, and marine species and habitats. Hanson has spent many years living in Charleston, S.C., but is currently splitting his time between Charleston and Chapel Hill.

Follow Keith and Running for Rivers on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, or at RunningForRivers.com.

This guest blog by Neuse River brewing Company is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers series on the Neuse River and the Cape Rear River.

Keeping North Carolina’s Neuse River clean is critically important to us.

It is the longest river in the state and the vein of our land. It feeds the community and everything around us, from bear to fish to insects. Its waters keep the environment alive.

Many people only know the river through their water faucet because it supplies water that they drink, cook with, and bathe in. However, keeping our river clean is critical for more than just water supply reasons. There is a carbon footprint left by treating and moving water. So, having clean water to start is imperative to reducing the effects of global warming.

It is also important to note that the river drains the landscape all the way to the ocean; when it is polluted, it pollutes our coast.

From a personal perspective, we enjoy biking on the Greenway Trail, kayaking, and being on the water. If the Neuse River is not taken care of, our children and our children’s children won’t have the opportunity to enjoy all the beauty and benefits it provides to us.

We are not just connected to the Neuse through our personal lives, we are also connected to the Neuse through our professional lives, so much so that we named our business after the river: Neuse River Brewing Company. We depend on reliable clean water to brew our beer. As brewery owners, having clean water is vital to our ability to produce a quality and consistent product.

Without protections put in place to keep the river clean, our quality of life would be greatly diminished. We all need to work together to keep the Neuse River swimmable, fishable, and drinkable.

Please join us in asking the Commissioner of the N.C. Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Steve Troxler, to champion the protection of this vital natural resource by pushing for full funding of the floodplain buyout program.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/1257/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

Author: Jennifer and Ryan Kolarov

Author: Jennifer and Ryan Kolarov

Jennifer and Ryan are co-owners of the Neuse River Brewing Company in Raleigh, NC, which specializes in Belgian style ales and IPAs.

Every spring, a distinct population of orcas known as the Southern Resident Killer Whales (SRKW) waits at the mouth of the Columbia River like students in a cafeteria line. On the menu: 30+lb spring chinook salmon, the largest and fattiest of the six salmon species found off the Puget Sound.

The Center for Whale Research estimates that the average SRKW consumes between 18-25 salmon per day. With only about 80 members of this population left, that’s 1,500-2,000 salmon every day! Chinook are their favorite by far, making up as much as 80% of these whales’ diets, though they also enjoy a sampling of coho, chum, and steelhead.

Anadromous fish have a complex life-cycle, one that begins in freshwater streams, segues into the ocean, and ends in the same stream of the salmon’s birth, where the ones who don’t end up an orca’s lunch return to spawn and die. They are a remarkable, resilient keystone species but they are vulnerable at every stage of that life cycle.

Rivers that historically produced millions of salmon now suffer from dams, lack of fish passage, overfishing, algal blooms, non-point source pollution, and the disconnection and development of floodplains. The oceans themselves are growing more acidic, impeding salmons’ ability to detect predators and survive to spawn the next generation. As salmonid populations dwindle, meals for the SRKW grow fewer and farther between. Luckily, efforts are underway to restore salmon populations and habitats, and to help them face the challenges of a changing climate. American Rivers is deeply involved in such work in the Pacific Northwest.

Most of us probably don’t think of riverine floodplains as important habitat for healthy Killer Whales. In fact, many people probably don’t even think of floodplains as habitat at all! A ‘floodplain’ tends to take on an array of different definitions depending on who you’re talking to. A community land-planner might tell you about the 100-year floodplain, or an area with a 1% chance of flooding each year that’s risky to build on. A hydrologist would tell you that a river’s floodplain is the land that gets inundated by water during high flows, or floods. An ecologist might explain that a floodplain is a unique ecosystem in between water and land, with plants and wildlife adapted to seasonal floods. A floodplain is all of these things in reality, and plays a key role in how rivers function. Where floodplains are connected to a river they provide space to convey floodwaters, capture excess sediment and nutrients, and provide productive habitat for a diversity of fish and wildlife.

Picture of Indian Creek in the Teanaway Community Forest, near Cle Elum, WA. Headwaters to the Yakima River and spawning area for Steelhead and other salmonids in the Columbia River Basin. | Photo: Jonathon Loos

In the Pacific Northwest native salmon populations spend the beginning and end stages of their life in rivers. Floodplains play a critical role in the life history of many salmonid species including Chinook, Coho and Chum salmon, which use flooded lands and side-channels for spawning and rearing as juvenile fish.

Today many species of salmon native to California, Oregon, and Washington are listed as threatened or endangered through the Endangered Species Act. Declines in these fish are primarily attributed to fragmentation of their freshwater habitats by the damming of rivers, and urbanization of floodplains and forests over the past century. As populations of salmonids have declined in river systems across the Puget Sound and Columbia River Basins, the SRKW that depend on those fish as food have also suffered. This is why connected, naturally functioning floodplains are important not just to healthy rivers, but also to the health of marine mammals, and entire coastal ecosystems!

Luckily, Washington is a good place to work on floodplain reconnection and restoration. Communities in the Puget Sound region have realized the many benefits that come from having floodplains that act as, well, floodplains. By moving old infrastructure such as levees, or repetitively damaged buildings farther back from waterways, floodplains can be opened up and reconnected to rivers. As a result, floods that occur can actually be lower, slower to occur, and cause less-costly damage to communities. As an added benefit, the newly restored floodplains can again be accessible to fish and wildlife such as endangered salmon. Communities in Pierce and King Counties are leading the way in this type of work, investing in their floodplains to reduce flood risk to people, and to improve the health of their rivers.

The Lower Green-Duwamish River flowing through southern Seattle region, tightly controlled by levees and kept bare of vegetation, this river is often too hot and polluted for Chinook salmon to survive during summer runs, reducing prey availability for Southern Resident Killer Whales. | Photo: Jonathan Loos

There is still a lot of work to do, especially in urban areas where less open-space still remains for reconnecting floodplain lands. The Lower Green-Duwamish River is one example; flowing through the Cities of Kent, Tukwila, and industrial areas of Seattle, the Green-Duwamish is leveed and tightly controlled like a canal. High levels of urban stormwater runoff, and a lack of shading from riparian vegetation create a waterway that is too polluted and too hot for many fish to thrive. Furthermore, there is a lack of complex instream and side-channel habitat that many fish need for spawning and resting. Addressing these threats through an improved Lower Green River Corridor Plan that considers both the need for flood safety and a functioning river ecosystem will be key to recovering fish populations and relieving pressure on SRKWs. That process is just beginning in the King County Flood Control District, and American Rivers will be engaged to help meet these needs.

In headwater regions where rivers begin, such as the flanks of the Cascade Mountains, meadows and floodplains are important for storing snowmelt water throughout the spring and summer, sustaining groundwater levels and the base-flows of streams and rivers to keep them flowing and cool during even the hottest and driest months of the year. In some watersheds, intensive grazing and logging practices over the past two centuries has impaired the capacity of headwater streams and floodplains to store water and support complex habitat needed by fish and wildlife. Investing in these headwater areas can improve base-flows to meet ecological needs and improve those lands for recreational use by people. Benefits from these projects flow downstream all the way to the Puget Sound, as water supply improves and anadromous fish species recover, and SRKWs continue to have nice fatty fish to eat each year.

Orca Awareness Month:

Killer whales, orcas, SRKWs, blackfish, they’re iconic by any name. So how can you help support their recovery?

Learn about salmon habitat restoration efforts in your area

In Washington, the Recreation and Conservation office created a Salmon Recovery Funding Board to provide grants for salmon restoration, protection and assistance programs. In Oregon, the Water Resources Department created a Plan for Salmon and Watersheds which combines voluntary restoration actions with state, federal and tribal projects, monitoring and scientific oversight. NOAA has also developed comprehensive recovery plans by region and species. And, of course, your local river or coastal groups are sure to have information available.

Learn about local fish passage efforts

Dam removals, culvert replacements and fish passage installation are all important tools in the work to boost salmon populations. The wildly successful Elwha Dam removal resulted in a local chinook boom. Chinook, coho, and sockeye have returned to the Yakima for the first time in a century, thanks to the construction of new fish passage systems. Find out what’s going on near you, and get involved! Lend your voice in support, attend public meetings, or help boost their activities through social media.

Support organizations that restore salmon-bearing streams

American Rivers is one of many PNW nonprofits that work in local communities to organize, restore, fundraise, and lobby for the health of our rivers and the wildlife who depend on them. Learn more about our work, and help us stretch it further in the future.

Every spring, a distinct population of orca whales known as the Southern Resident Killer Whales (SRKW) waits at the mouth of the Columbia River like students in a cafeteria line. On the menu: 30+lb spring chinook salmon, the largest and fattiest of the six salmon species found off the Puget Sound.

The Center for Whale Research estimates that the average SRKW consumes between 18-25 salmon per day. With only about 80 members of this population left, that’s 1,500-2,000 salmon every day! Chinook are their favorite by far, making up as much as 80% of these whales’ diets, though they also enjoy a sampling of coho, chum, and steelhead.

Anadromous fish have a complex lifecycle, one that begins in freshwater streams, segues into the ocean, and ends in the same stream of the salmon’s birth, where the ones who don’t end up an orca’s lunch return to spawn and die. They are a remarkable, resilient keystone species but they are vulnerable at every stage of that life cycle.

Rivers that historically produced millions of salmon now suffer from dams, lack of fish passage, overfishing, algal blooms, non-point source pollution, and the disconnection and development of floodplains. The oceans themselves are growing more acidic, impeding salmons’ ability to detect predators and survive to spawn the next generation. As salmonid populations dwindle, meals for the SRKW grow fewer and farther between. Luckily, efforts are underway to restore salmon populations and habitats, and to help them face the challenges of a changing climate. American Rivers is deeply involved in such work in the Pacific Northwest.

The Yakima Basin:

Washington’s Yakima River once boasted the second-largest salmon run in the Columbia system. More than 800,000 chinook, coho, sockeye, steelhead, and cutthroat returned to spawn in its tributaries every year. Their presence supported the Yakama Nation and other Columbia Basin tribes, as well as complex headwater ecosystems throughout the Central Cascades.

Competing demands on the Yakima River’s waters did not turn out in favor of the fish. As agriculture grew, large irrigation reservoirs were constructed without fish passage facilities. In just a few decades summer chinook, coho, and sockeye went locally extinct, while spring and fall chinook barely hung on alongside steelhead. Thanks to lack of passage, low and altered flows, increasing temperatures, overfishing, and past land mismanagement, only 3,000-4,000 salmon remained in the Yakima system by 1990.

After a devastating series of droughts in the 90s and 00s, an unprecedented group of stakeholders came together to discuss the Yakima Basin’s water supply woes in 2009. Realizing that suing one another wasn’t providing anyone with the water they wanted, government agencies, tribal entities, irrigators, county commissioners, recreation groups, and environmental nonprofits convened a Workgroup to sort out what each group needed. The result was the Yakima Basin Integrated Plan, a laundry list of fish passage, water conservation, habitat restoration, surface and groundwater storage, water marketing, and irrigation efficiency projects that will provide reliable water for all parties within the basin. Fish passage projects are among the Integrated Plan’s first major construction efforts. Crews have already broken ground on a one-of-a-kind downstream helix passage system at Cle Elum reservoir. The other four Yakima Basin dams are undergoing studies to determine the best approach to provide fish with passage to spawning and rearing habitat blocked off for a century or more.

Before the Integrated Plan came together, the Yakama Nation Fisheries were hard at work returning chinook, coho, and sockeye to the basin. They drafted inter-tribal agreements to transplant salmon from other basins and established local hatcheries where they rear supplemental stock. Yakama Nation biologists join forces alongside partners like American Rivers, Trout Unlimited, and The Wilderness Society to restore instream habitat and reconnect rivers to their surrounding floodplains, giving salmon and steelhead a fighting chance against habitat degradation, development, and climate change.

Orca Awareness Month:

Killer whales, orca whales, SRKWs, and blackfish are iconic by any name. So how can you help support their recovery?

- Learn about salmon habitat restoration efforts in your area

In Washington, the Recreation and Conservation office created a Salmon Recovery Funding Board to provide grants for salmon restoration, protection, and assistance programs. In Oregon, the Water Resources Department created a Plan for Salmon and Watersheds which combines voluntary restoration actions with state, federal, and tribal projects, monitoring and scientific oversight. NOAA has also developed comprehensive recovery plans by region and species. And, of course, your local river or coastal groups are sure to have information available.

- Learn about local fish passage efforts

Dam removals, culvert replacements, and fish passage installation are all important tools in the work to boost salmon populations. The wildly successful Elwha Dam removal resulted in a local chinook boom. Chinook, coho, and sockeye have returned to the Yakima for the first time in a century thanks to the construction of new fish passage systems. Find out what’s going on near you, and get involved! Lend your voice in support, attend public meetings, or help boost their activities through social media.

- Support organizations that restore salmon-bearing streams

American Rivers is one of many Pacific Northwest nonprofits that work in local communities to organize, restore, fundraise, and lobby for the health of our rivers and the wildlife who depend on them. Learn more about our work and help us stretch it further in the future.

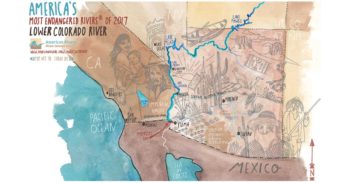

One would be hard pressed to find a river more important to a region than the Lower Colorado.

The river provides drinking water for nearly 30 million people from Las Vegas to Phoenix to Los Angeles. It irrigates millions of acres of farmland, growing the vast majority of our nation’s winter vegetables in places like Yuma, Arizona and California’s Imperial Valley. All told, if the river disappeared today, the United States would lose hundreds of billions of dollars in annual economic output.

While the river is not going to disappear, there is a very real possibility that over the next several years, water deliveries will be cut to some users because we collectively use more water than the river can provide. It is also likely that water availability will continue to decline due to rising temperatures caused by climate change. Even incremental cuts to water supply will have a huge impact on the environment and the regional economy. For example, in the event of a shortage, initial cuts would take water from Arizona’s agriculture industry, forcing farmers to either fallow their land or increase groundwater pumping to water their crops. Further cuts would literally dry up most of Central Arizona agriculture. Many aquifers across the state are already depleted, and when the groundwater goes, so does the desert environment, biodiversity, and quality of life.

Some may ask, why list the Lower Colorado River when it’s hardly a river; most of it has been piped, diverted, or dammed? Or some may say, why focus on this threat when clean water, public lands, and our bedrock environmental laws are under attack? The answers to these questions are straight forward – the river is too important, and the consequences to the environment and the economy are too severe – if we do not continue the progress made to address the water imbalance by Arizona, California, Nevada, the Federal Government, and others through agreements like the Drought Contingency Plan (DCP) and the Drought Contingency Plan “Plus” (two key collaborative agreements currently in negotiation) in Arizona. While there are many legitimate and combative environmental public policy debates happening in the country right now, water is a non-partisan issue.

In the DCP agreement, the Lower Basin States are negotiating voluntary cuts to Colorado River water deliveries in order to stabilize the system and avoid deepening water shortages. Each state is also developing a plan for municipalities, citizens, and industry to adapt to a potential reduction in water. Arizona in particular, where this plan is called “DCP Plus,” entails additional conservation measures, innovative water sharing approaches, and enhanced efforts specifically designed to avoid water shortage, before it’s too late. DCP and DCP Plus were nearly completed at the end of 2016 after more than a year of negotiation with the leadership and support from the Federal government. It is critical that the federal government and congress continue this leadership, support, and funding for these efforts to ensure water supply security and environmental protection of the river and the livelihoods of millions of people across the Southwest.

If efforts like the DCP are going to be successful in the long term, it is essential that diverse voices are engaged in Colorado River issues. This is why the Hispanic Access Foundation has partnered with American Rivers on this year’s Most Endangered Rivers report. Two years ago, the Hispanic Access Foundation and American Rivers produced a short film called Soy Rojo which screened at dozens of churches throughout the Colorado River Basin. Powerful voices within the Latino Faith community emerged from these screenings, highlighting the cultural, spiritual, and economic importance of the Colorado River to Latino communities from Colorado to California. We are proud to partner with the Hispanic Access Foundation on this listing and on our second film together – Milk and Honey – which tells the story of one communities’ connection to the Colorado River near Yuma, Arizona.

Our 2017 America’s Most Endangered Rivers report highlighting the Lower Colorado river illustrates the need for us all to come together, whether you live in Yuma or New York, to develop and promote smart solutions to our most urgent river issues. By working together, and with support of leadership at all levels, we can sustain the Lower Colorado River that works so hard for all of us.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/214/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”4″ center=”yes”]Take Action »[/su_button]

North Carolina’s Neuse and Cape Fear rivers are threatened by untreated animal waste that is stored in the floodplains of the rivers and can be washed into the river during flood events like what occurred after Hurricane Matthew in 2016.

Over the next few weeks, we’ll introduce you to a series of posts that explore different aspects of the Neuse River and the Cape Fear River, #7 rivers on the list of America’s Most Endangered Rivers® of 2017.

Welcome to the Neuse and the Cape Fear Rivers

The Neuse River and the Cape Fear River systems flow out of the heart of North Carolina. They have modest beginnings in the foothills of the state near the border with Virginia. The Neuse River is one of the iconic rivers of North Carolina; at its mouth is New Bern, a city founded in 1710 that served as the original capital of the state and remains a center of maritime and agricultural commerce, and at its headwaters is the current capital, Raleigh. The Cape Fear River derives its name from the peninsula of land where the river meets the Atlantic Ocean, but the river pulls from the heart of North Carolina 200 miles inland. The Cape Fear has supported robust shipping commerce over the state’s history. The vast longleaf pine forests of the lower watershed enabled this trade as hundreds of distilleries crafted basic materials from the trees for storing and transporting supplies across the sea: tar, pitch, turpentine, and rosin. It is from this industry that North Carolina developed its nickname as the ‘tar heel state.’

The main stem of these rivers tend to be broad flowing rivers with limited whitewater ideal for easy paddling trips and observing the landscape surrounding them. The rivers drain a watershed that is about 15,000 square miles and have nearly 10,000 miles of stream amongst them. More than four million people in North Carolina get their drinking water from the rivers, including the growing cities of Raleigh, Durham, Fayetteville, and Wilmington. In addition, the estuaries of these two river systems play a large role in the economically important seafood industry, accounting for more than 90 percent of the commercial seafood species caught in North Carolina. The Neuse and Cape Fear rivers are vital to supporting North Carolina’s $1.7 billion fishing industry.

What’s at Stake?

The Neuse River and Cape Fear rivers have suffered for decades from harmful algal blooms due to excessive amounts of nitrogen and phosphorous. While this pollution has many sources, the most prominent are human and animal waste and stormwater runoff. In the wake of Hurricane Matthew (2016), one of the greatest successes and tools for protecting the health of the rivers from nutrient pollution was realized — eliminating animal waste lagoons and piles from the 100-year floodplain.

North Carolina is the second leading producer of hogs and the third leading producer of poultry in the country. Much of North Carolina’s animal production occurs in the Neuse and Cape Fear watersheds. Hundreds of millions of gallons of wet animal waste from these operations are held in open lagoons, and tons of dry waste is piled in fields near the concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs). Within the 100-year floodplain of the coastal counties, 62 swine CAFOs house more than 235,000 hogs and at least 30 poultry CAFOs house over 1.8 million chickens and turkeys. There are 166 open-air waste pits directly within the 100-year floodplain, and another 366 within 100 feet of the floodplain.

The flooding from Hurricane Matthew in Craven, Duplin, Green, Jones, Lenoir, Pitt, Sampson, and Wayne counties, partially submerged 10 industrial hog facilities with 39 barns, 26 large chicken-raising operations with 102 barns, and 14 open-air pits holding millions of gallons of liquid hog manure, releasing untreated waste directly into the rivers.

What can be done?

There is a simple and commonsense action that can be taken to reduce the threat to our water resources and communities — remove the existing industrial CAFO facilities from the floodplain. A highly successful program to move waste operations out of the 100-year floodplain was developed after Hurricane Floyd in 1999, which was the last major flooding event to impact the rivers. The state of North Carolina spent $18.6 million to close 42 swine facilities with 103 waste pits.

The program has run out of funding and there are no other viable funding options for farmers to move their waste operations out of the floodplain. There are 92 CAFOs and their associated waste operations within the floodplain that need to be relocated to protect the health of the Neuse and the Cape Fear. It is time to restore the Swine Buyout Program and include language expanding it to all CAFOs in the floodplain as part of the Hurricane Matthew recovery package.

Please join us in asking the Commissioner of the N.C. Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Steve Troxler, to champion the protection of this vital natural resource and protect the investments of family farmers by pushing for full funding of the floodplain buyout program.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/1257/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

Rivers run through the lives of our children in so many ways.

They give us our drinking water. They water the fields that grow the fruits and vegetables we eat. They give us beauty, serenity, adventure. They are where we reconnect with the natural world, our friends and family, ourselves.

There are few things more fundamental to the health of our families than clean drinking water. But too many families in our country today are forced to live with polluted rivers and unsafe drinking water.

Top 3 reasons why your family needs healthy rivers:

1. Your kids need clean drinking water.

Nationwide, rivers provide more than half of our drinking water supplies. Rivers flow through our veins. So when rivers are polluted, that raises health concerns – for moms, for babies, for all of us. As our kids grow up, we want to know that the water flowing from our taps is clean and safe. Too many communities in our country (it’s not just Flint) do not have access to safe drinking water.

Imagine if our decision makers and members of Congress understood our bodies – their own bodies – as directly connected to the health of rivers and the natural world. Instead of slashing clean water safeguards, as they are doing now, we’d be having a much different conversation about ensuring the health of American families for generations to come.

2. Playing outside is good for kids’ brains and bodies.

Children need to play, and they need to play outside. The natural world is full of opportunities for fun, wonder, discovery, and exercise. Studies show that when kids get outside, they do better in school. Richard Louv writes about the many benefits of nature for kids and adults, including reducing depression and building family and community bonds.

Child playing on the river. | Photo: Amy Kober

It’s important that we insist on public access to rivers, safe parks, and other outdoor areas for all communities, urban and rural, big and small. Every child should have a chance to connect with her river and reap all of the benefits of outdoor play.

3. It’s their birthright.

Your kids own the rivers. We all do. Rivers are public resources, benefitting all Americans. And rivers connect us – past, present and future. Rivers are an essential part of our country’s heritage. From the Lewis and Clark expedition, to Huck Finn, to the poetry of Langston Hughes, rivers flow through our history, art, music, and literature.

The Potomac, the Yellowstone, the Shenandoah, the Mississippi, the Colorado, and the river flowing through your town: Your children are inheriting all of this, and they will pass it on to the next generation.

June is National Rivers Month – Here are three ways to celebrate:

Participate in a river cleanup

Join the millions of volunteers who are cleaning up trash from rivers and streams, and giving back to their communities. Learn more »

Share your river story

Why are rivers important to you and your family? Share a photo or a special memory with us! Share your story »

Call your member of Congress

Did you know that President Trump is proposing massive cuts to clean water safeguards in the federal budget? Tell your member of Congress to oppose any effort by President Trump or Congress to cut funding for river conservation and clean water protection. (Find contact info for your representative and senators).

Get out and enjoy your rivers, share your story, and speak up to your decision makers!

The Upper Cle Elum, Cooper, and Waptus rivers are not part of the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System, a fact that surprises many visitors and local residents. You only have to stare into the clear depths of the Cooper River swimming hole, hike the Waptus outcroppings into the Alpine Lakes Wilderness or stroll through the wildflower meadows bordering the Upper Cle Elum wetlands to understand why; the area is prized for its beauty, diversity, and broad array of recreational opportunities. Hiking, fishing, birdwatching, camping, horseback riding, canoeing, kayaking, and more are available within the Upper Cle Elum River system, supporting the economic vitality of nearby communities and quality of life for locals.

These three rivers are also a key component of the Yakima River headwaters. They provide clean and cool water to fish and wildlife, as well as drinking and irrigation water to towns in Kittitas and Yakima counties. And thanks to fisheries restoration efforts by the Yakama Nation and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, they’re home to the first sockeye salmon to be found within the Yakima basin in more than a century! It is no wonder then that community leaders, environmental groups, and outdoor clubs feel that these rivers should be protected under a Wild and Scenic River designation.

The Wild and Scenic Rivers Act was signed into law in 1968 at the height of the modern dam-building era. It prohibits federal involvement in new dams, diversions, or other development that would harm a designated river’s free flowing condition, water quality or quantity, or unique values. This landmark law is the highest form of protection available to rivers in the United States, though less than ¼ of 1% of America’s rivers are currently designated.

A Wild and Scenic River designation identifies and creates a management plan to protect a river’s “outstandingly remarkable values.” These can be recreational, scenic, ecological, geological, archeological, or historic values. Anything that sets the river apart on a local, regional, or national scale is considered within the designation. The Upper Cle Elum and Waptus rivers were recommended to receive this protection by past Forest Service planning efforts, while the Cooper was found eligible for further consideration. The need for future management planning has only increased as sockeye salmon return to spawn in these rivers once again, and a growing Washington population seeks out quality recreation experiences on the East Side.

Best of all, the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act mandates that communities be involved in creating a Comprehensive River Management Plan for every designated river. American Rivers is working toward designation of the Upper Cle Elum System as part of the Yakima Basin Integrated Plan, a comprehensive approach to water management and habitat enhancement throughout the Yakima River Basin.

This story was originally published as part of the NW League of Whitewater Racer’s newsletter.

Join us to protect wild rivers and public lands. To celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act in 2018, we are teaming up with partners to ask Congress to protect 5,000 new miles of Wild and Scenic Rivers and one million acres of riverside lands.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/863/petition/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

“We’re now living in a world of extremes on the Mississippi River,” Mayor Brant Walker of Alton, Illinois told E&E News last month. “We just don’t get normal spring rains anymore. We get huge downpours.”

The community of Alton isn’t alone. Flooding has devastated communities from South Carolina to California in recent years, while drought and water scarcity have squeezed Georgia, Arizona, and other states.

These are the kinds of impacts we’re seeing with climate change – and we may see more, now that President Trump is withdrawing the U.S. from the Paris Climate Agreement.

There’s no doubt that climate change is hitting our rivers and water resources “first and worst”. Without bold action to stop climate change, more severe floods and droughts, more waterborne diseases, and increasingly scarce water supplies will threaten communities in the United States and around the world.

Since our founding in 1973, American Rivers has been about solutions that work for people and rivers. And now our work is more important than ever.

That’s because, in addition to fighting dirty fossil fuel pollution, we are leading the charge to help communities build their resilience to climate impacts with river conservation solutions, such as:

- Making cities like Atlanta, Milwaukee, and Tucson more water efficient

- Restoring floodplains to absorb floodwaters and build wildlife habitat

- Protecting wild rivers, healthy forests, and streams that naturally sustain clean water supplies

- Improving our nation’s crumbling water infrastructure

Thanks to the work of American Rivers and our nation’s strong river community – including non-profit advocates, scientists, water managers, businesses, and other leaders – the United States is a global leader in river restoration and protection.

As Bob Irvin, the president of American Rivers, stated, “President Trump’s head-in-the-sand approach to climate change contrasts sharply with the leadership and moral courage of countless individuals, businesses, and cities that are working tirelessly to stop dirty fossil fuel pollution and strengthen communities against climate impacts including increased flooding and drought.”

“American Rivers will continue to stand with these local leaders, and we will continue helping communities build their resilience with innovative river conservation solutions. We will work to ensure the United States remains a global leader in river restoration and protection, because a healthy river is a community’s best defense against the impacts of climate change.”

Learn more: Resources on Climate Change and Rivers

This guest post, from Stephanie Curin, is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Bear River.

Every visit to the Bear River is precious because that’s when you get to hear the music of the river.

No sound on earth compares to the soothing rush of water as it travels over stones, through willows, and around each river bend. There is a timeless quality about a river that whispers of the past, talks into the present and gives hope for the future.

Recently, when walking along a path next to the river, I was keenly aware of the changing volumes of the rushing water. Sometimes it was a quiet, gentle flow, then a few steps further on the river gathered speed as the rapids loudly crashed over rocks and branches in its path. Next was a place where the water moved forward at a steady pace, sounding like a constant wind coursing through the waters.

Often our lives parallel with the flow of a river. We go through peaceful times when everything is smooth and hushed, then suddenly a storm comes along and we’re tossed about in the turbulence of our circumstances. All seems loud and the calm is drowned out. Then there are days we move steadily forward, one wave at a time, through the ongoing routine of daily existence. These wonderful sounds of the river give clarity and reassurance as they echo our daily walk through life.

Another beautiful sound of the river is the tumble of rocks under the water, as they move from one place to another. I first heard this as a child when our family camped along the banks of a small river in Idaho. After a full day of playing in the river, we gathered around the campfire telling stories and gazing into the flames. When it got pitch dark, and the night was bright with stars, the grown-ups shuffled us kids off to bed. The distant rise and fall of adult voices were barely audible, as the tales became more interesting and the fire crackled as the moon rose in the sky. It was difficult going to sleep. I tossed and turned in my sleeping bag straining to hear more of their stories.

But after a while, the river music began. First, it was an incessant hum. The more I listened, the more varied it became as it muffled the other sounds of the night. The swift current ebbed and flowed into the deep rumbling of stones turning over in the waters of the river bed. It reminded me of my father’s voice, low and calm, gentle and deep. Soon the river music lulled me peacefully to sleep. A sound from childhood I have never forgotten. You must be very still and quiet to hear the murmur of rocks tumbling in a river.

River music is an irreplaceable sound that is worthy of being treasured and preserved. It speaks volumes as it calms the soul. Whatever my mood is— happy, sad, restless or fretful— the river gives me peace, a deep down sense that all is well as the water moves constantly forward to the sea. The sound of the river heals, teaches, and renews when we make the time to listen to its low, steady voice.

Help us keep this special river flowing

One of the Bear River’s last free-flowing reaches is threatened by an expensive, damaging and unnecessary new dam. Damming the river is a 19th-century solution to the 21st-century challenge of a changing climate. Tell the Nevada Irrigation District to stop this expensive, risky and unnecessary dam project at the expense of local communities and ecosystems.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/716/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

Stephanie lives with her family in Colfax, California, near the Bear River recreation area and regularly visits the river to go hiking on its many trails. She is a member of the local garden club and enjoys creating natural plant habitats to support native pollinators and migratory birds. Currently, she is volunteering to raise awareness of the threatened Bear River.

Stephanie lives with her family in Colfax, California, near the Bear River recreation area and regularly visits the river to go hiking on its many trails. She is a member of the local garden club and enjoys creating natural plant habitats to support native pollinators and migratory birds. Currently, she is volunteering to raise awareness of the threatened Bear River.

President Trump will arrive in Cincinnati to talk about his vision for the nation’s infrastructure. He could learn something from Cincinnati — and Ohio — when it comes to innovative solutions for water infrastructure.

There are few issues more vital to our health than clean water, and rivers provide much of our nation’s drinking water supplies. But nationwide, our water infrastructure – including pipes, sewage treatment systems, locks, and dams – is crumbling.

Problems ranging from water contamination due to lead pipes in Flint, Michigan, to safety concerns at the nation’s tallest dam in California have grabbed national headlines. The American Society of Civil Engineers gives our nation’s dams, drinking water systems, and levees a “D” grade in its 2017 report card on the nation’s infrastructure. The impacts of outdated water infrastructure and water management fall disproportionately on low-wealth neighborhoods and communities of color that are already suffering from a lack of investment and opportunity.

Many cities, including Cincinnati, are moving in the right direction to confront water challenges with innovative, cost-effective solutions that recognize healthy rivers and streams as an essential part of a community’s infrastructure. The Metropolitan Sewer District of Greater Cincinnati (MSD) has embarked on a multi-year initiative to clean up polluted rivers while creating social and economic opportunities for communities. MSD’s efforts include capturing stormwater with bioswales and restoring streams to improve water quality and decrease local flooding.

Statewide, Ohio has done a good job restoring river health through the removal of unsafe, unneeded dams. The Cuyahoga River, once a symbol of environmental degradation, is now a symbol of restoration thanks in part to the removal of outdated dams. Downtown Columbus has reconnected to the Scioto River after removing dams and restoring wetlands.

Any federal investment in water infrastructure must advance these types of 21st-century solutions so we can ensure reliable clean water supplies and safe, healthy communities for our children and grandchildren.

Specifically, federal investment must

1) Update water systems to ensure public safety

We must replace decaying and dangerously out-of-date drinking water systems (such as lead pipes) and upgrade wastewater treatment plants.

2) Prioritize natural infrastructure

We need a new kind of water management and we need it in the right places. Solutions that protect, restore, and replicate natural systems and use water efficiently have a wide range of social, economic, and environmental benefits. Natural infrastructure can mean planting trees and restoring wetlands, rather than building a costly new water treatment plant. It can mean choosing water efficiency instead of building a new water supply dam. It can mean restoring floodplains instead of building taller levees.

3) Remove outdated infrastructure

Many locks and dams provide benefits, but many others have outlived their usefulness, creating an economic drain on communities or dangerous public safety hazards. Nearly 1,400 dams have been removed nationwide and efforts continue. For example, efforts are underway to remove Gorge Dam on the Cuyahoga, and the Army Corps is currently studying whether to retire five locks and dams on the Allegheny River, a tributary of the Ohio River.

4) Maintain environmental safeguards

When deciding how to address our infrastructure needs, we must not forego the protections provided by laws such as the National Environmental Policy Act, Clean Water Act, and Endangered Species Act in our haste to move projects forward. These laws enable us to look before we leap and think about which path will provide the best and most environmentally-sustainable, long-term solution for our needs.

Clean water can and should be a bipartisan issue. Healthy rivers are economic engines and water is an excellent investment: every $1 spent on water infrastructure generates nearly $3 to the private economy, according to the U.S. Department of Commerce. Rivers helped build Cincinnati, and they helped build our nation. Investing in healthy rivers and innovative water infrastructure solutions will strengthen our country and pay dividends for generations to come.