Guest post by Andrew Whitehurst is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Pearl River.

In the Lower Pearl River system, between Mississippi and Louisiana, there are good things happening. Projects to restore river function and to improve coastal habitats near the Pearl’s mouth are either under way or are in the final planning stages. But efforts to build a new dam and lake upstream in the Jackson area are indefensible.

As the Lower Pearl River is receiving some desperately needed restoration, a private-public enterprise is about to unveil its dubious proposal to build a costly dam and lake in the Jackson metro area. If this proposed dam gets approved and funded, it can negatively impact the Pearl all the way to the Gulf.

Great things are happening on the Pearl through public-private partnerships, but the Rankin-Hinds Pearl River Flood and Drainage Control District is supporting the “One Lake” proposal of the private-non-profit “Pearl River Vision Foundation (PRVF).” The PRVF is using public money to promote a dam and lake and to lobby Congress for approval and public funding.

The restoration happening on the Pearl will be undone by a lake and dam. And flooding can be managed more wisely and effectively without a lake and dam. Here is a look at some of the Pearl-related restoration projects:

In Mississippi, some of the earliest projects funded by the BP oil spill settlement were focused on restoring more than 1,450 acres of hard bottom in the Western Mississippi Sound for oyster reef restoration.

The Bayou Heron Living Shoreline project is using $50 million of settlement money to restore and protect shoreline, create new marsh and build oyster bottoms, from the mouth of the Pearl River eastward six miles toward Bayou Caddy in Hancock County.

Two other projects funded by BP settlement money will study the impacts of water movement in the Pearl and the Gulf, the balance of saltwater and freshwater in the western Mississippi Sound, and will model flow in the lower 40 miles of the Pearl. These studies are being undertaken by Mississippi State University, Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality and private contractors. Modeling freshwater flow in the Lower Pearl is important for predicting salinity and oxygen levels critical to the health of the coastal estuaries and the Gulf Coast’s recreational and commercial fisheries, and is foundational to the ultimate success of tens of millions of dollars-worth of oyster bottom and marsh creation work underway in the western Mississippi Sound and in southeastern Louisiana.

In 2014, the Louisiana legislature created the Lower Pearl River Ecosystem Study Commission to examine the conditions of the Lower Pearl and its needs for protection and preservation. Around that same time, St. Tammany Parish commissioned the Stennis Space Center to conduct a Lower Pearl River flow-study to help predict impacts from river flooding and storm surges.

In 2016, Congress transferred to Louisiana the Pearl River Navigation Canal project, below Bogalusa, so Louisiana could begin removing obstructions from the channel. Removing obstructions will open up more miles of important fish habitat than any other restoration project under consideration on any other river system in the five Gulf states.

Louisiana’s master plan for coastal restoration includes shoreline protection projects to slow erosion in the Biloxi Marsh. Also, marine resource agencies in Louisiana and Mississippi are collaborating to use dredge material to rebuild eroded land in St. Bernard Parish. Ongoing and future restoration depends on having enough freshwater from the Pearl — with the right volume, flow and timing. The Mississippi Commission on Marine Resources understands, and in 2015 passed a resolution against further inland damming on the Pearl and other coastal rivers. The Louisiana Oyster Task force understands, too, and in 2016 wrote a letter asking the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources to be ready to perform a review of the “One Lake” project when the proponents publish their draft Environmental Impact Statement later this summer. These agencies are rightly concerned.

Despite existing disruptions of the Pearl River, including the 53-year-old Ross Barnett Dam and Reservoir, meaningful river restoration is happening. The Pearl River can be improved, and its water quality and flooding can be addressed without further degrading this important Coastal Plain river. Smart projects are at work on the Pearl and more are on the horizon. Further altering the Pearl’s freshwater flow with more damming is counterproductive for ecosystems and even for flood control. State and federal decision makers, industrial and recreational users of the Pearl, local governments, tourism and commercial fishing interests, all need to acknowledge that the Pearl is in danger and needs to be protected for all of its beneficiaries, not just those looking for new government subsidized development opportunities in the floodplain.

Author: Andrew Whitehurst, Gulf Restoration Network

Author: Andrew Whitehurst, Gulf Restoration Network

Andrew Whitehurst is Gulf Restoration Network’s Water Program Director and works on water and wetland issues from Madison, MS.

Guest post by Cindy Lowry is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Mobile Bay Basin.

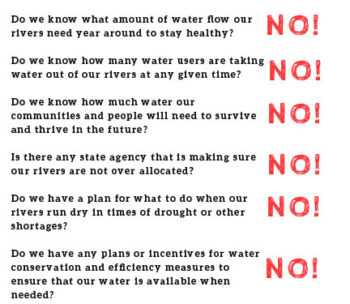

In April 2017, the entire Mobile Bay River system, which includes two thirds of the rivers and streams in Alabama, was named as one of America’s Most Endangered Rivers®. The lack of an Alabama Water Management Plan is leading to poor water management decisions within this important river basin.

What needs to happen right now to improve water management in Alabama?

Alabama’s new Governor, Kay Ivey, holds the key to moving forward on the state agency-led process that has been ongoing for the past five years. She has assured Alabama Rivers Alliance that she is doing her homework to get up to speed on this issue. We need her leadership now to release the Alabama Water Agency Working Group (AWAWG) report, which outlines recommendations for a state water plan. The Permanent Joint Legislative Committee on Water Policy and Management in the Alabama legislature has not met since last year. I feel strongly that Governor Ivey should ask them to meet and work to engage stakeholders in reviewing the AWAWG report to determine the next steps toward an adopted Alabama Water Plan.

Meanwhile, one legislator understands that the gaps in our current water management system need attention sooner rather than later. Representative Patricia Todd (D, District 54) introduced a bill during the 2017 session of the Alabama legislature to help move the state toward a better system for managing our water. The bill did not pass during the session, but she has assured us it will be reintroduced in 2018.

How do you think about rivers?

I think of rivers much like our bodies. Our bodies move us from place to place, enable us to think and do our jobs, raise our children, and – when healthy – they keep themselves sustained and running properly. When rivers are healthy, they are constantly working for us – diluting pollution, helping create electricity, providing food and recreation. We often take both for granted. When we take our bodies for granted, they begin to break down and then need proper care to maintain their important functions. Rivers are much the same. When they are not properly cared for and managed, they cannot provide all the water we need to drink, play, and to provide for our economic needs and quality of life.

I think of rivers much like our bodies. Our bodies move us from place to place, enable us to think and do our jobs, raise our children, and – when healthy – they keep themselves sustained and running properly. When rivers are healthy, they are constantly working for us – diluting pollution, helping create electricity, providing food and recreation. We often take both for granted. When we take our bodies for granted, they begin to break down and then need proper care to maintain their important functions. Rivers are much the same. When they are not properly cared for and managed, they cannot provide all the water we need to drink, play, and to provide for our economic needs and quality of life.

Caring for our bodies means understanding what our body needs as well as managing what we put into our bodies and how we use our body to keep it healthy. It’s the same with our rivers. We must understand their needs and manage them properly in order to keep them healthy and able to work for us. Alabama state leaders and stakeholders have been talking about this for more than two decades.

How we are we doing so far?

In the last 18 months throughout Alabama, we have experienced some of our deadliest floods (December 2015), our lowest stream flows ever recorded (summer 2016), and record rainfall (summer 2017). The amount of clean water we have available to us is growing increasingly unpredictable. We must invest in a plan to properly care for and manage our rivers if we hope to keep them clean, drinkable, healthy, and available to us into the future for ourselves and for future generations.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/712/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

Author: Cindy Lowry, Executive Director, Alabama Rivers Alliance

Author: Cindy Lowry, Executive Director, Alabama Rivers Alliance

Alabama Rivers Alliance is a statewide network of groups working to protect and restore all of Alabama’s water resources through building partnerships, empowering citizens, and advocating for sound water policy.

This guest blog by Deb Skubal and Doug Lichtfeld is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series on the Menominee River in Wisconsin and Michigan.

My husband and I are most frustrated being Wisconsin residents, living directly across the Menominee River from the Back 40 open pit sulfide-ore mining project, often finding that many fellow residents feel this impending threat only applies to those of us within site of the project.

Equally frustrating are the many calls and letters to elected officials, only to hear that the decision is with Michigan’s Department of Environmental Quality alone… saying there’s nothing they can do. Thankfully, due to persistence, we now do have several elected officials speaking up.

As we’ve persevered, we’re beginning to see a sleeping giant awaken… and not only Wisconsin residents. Many fishing clubs in other states are also sounding the alarm to save the Menominee River.

Today, we’re asking for your help in saving this river, important to all current and future generations, and to keep spreading the word… one by one our voice gets louder!

We cannot allow this massive sulfide mine in such a water rich environment be allowed to go forward. After all, there has never been a mine of this type to NOT pollute its waterways, when surface water and groundwater are present!

This is NOT a done deal!

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/702/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

Deb Skubal and Doug Lichtfeld own property within 1,320 feet of the Back 40 Project Boundary in Wisconsin.

One of the most complex river systems in the country, the Colorado River, journeys 1,450 miles through seven states, two countries, and supports 36 million people. Its water forms the foundation for agriculture, recreation, industry, and municipalities, from Denver to Tijuana, and fuels a $1.4 trillion annual economy.

Managing the hardest working river is no easy task.

More than a century ago, populations across the west were booming. The seven states dependent on the Colorado River recognized the need to formally divide it, ensuring everyone received an appropriate amount of water. Ratified in 1922, the Colorado River Compact marked the beginning of how and why the Colorado River is managed as it is today. However, the Compact’s underlying analysis was based on one of the wettest 10-year periods in history; meaning that the Colorado River Compact is actually based on an allocation of water that isn’t there. And never will be there in any reliable way.

But the Compact is only one thread in a much larger story. Because the whole basin’s demand for water is higher than what it can supply, the Colorado River has become both one of the most stringently managed, as well as aggressively disputed, rivers in the world. There are numerous other compacts, federal laws, court decisions, decrees, contracts, and guidelines that have been developed since the 1922 compact that dictate the challenging management of the Colorado River; these are collectively known as the “Law of the River.”

Join us this week and next on the We Are Rivers: Conversations about the Rivers that Connect Us podcast, where we chat with John Fleck and Amy McCoy, both respected voices about the “Law of the River,” and the challenges, successes, and collaborations that have occurred to both harness and protect the bounty that is the Colorado River.

This guest blog by Anahkwet/Guy Reiter is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series on the Menominee River in Wisconsin and Michigan.

First, I would like to acknowledge my ancestors, who endured so much so that we could have what we have today. I’m forever in your debt. Waewaenon Ketaenon (I say thank you)!

Posoh, Anahkwet newiswan, Wapaesyah netotaem. My name is Guy Reiter, and I just introduced myself in my Menominee language. My elders taught me to always introduce myself and my clans before I speak to a new audience.

It’s hard for me to write down what I want to say because I value the spoken word over the written word. So I’m going to write as if I’m sitting with you speaking.

My Tribe, the Menominee Indian Tribe, is the longest living inhabitant of this land that is called Wisconsin. Like most Tribes in America, we’re one of the most studied peoples on the planet. Our beginning as a Tribe begins a mere 60 miles northeast of our current reservation at the mouth of the Menominee River. The city of Marinette, Wisconsin, now lies on that sacred site. Our oral history states that this is the place where our creation began thousands of years ago.

In order to know my Tribe, you have to start with the creation of my Tribe. This creation story can be looked up on the internet or in a book (just take care to remember that the people writing the story were using translators, and a number of things can get lost in translation). The Menominee Creation Story was told to me by one of our elders on the reservation when I started to organize against the Back Forty Mine. We, Menominees, were given the responsibility to look after that river and land by the creator thousands of years ago, and that supersedes any treaty or law. (This article isn’t designed to inform of our whole history, it’s just giving you a very small piece.)

The Menominee River is a part of me; its essence is within my soul. There isn’t a Menominee Indian around who wouldn’t feel connected and unified standing next to the river while gazing upon its sacred banks and water.

If a mine were to pollute the Menominee River, worse than what it already is, it would devastate my fellow Menominees and I. Putting a mine on this location is just the same as if they were to drill for oil in the Garden of Eden. Imagine what people would say when asking them to describe how it feels to see this mine polluting their sacred area.

Not only that, but to ask people to go to meetings and draft up comments in order to try and let people understand how this project affects them on a much deeper level.

Ask people to try and hold back tears when decision makers who don’t have the same connection to that sacred area tell about how they’re going to protect it better than ever before, how the technology has changed so much in the last few years, and that the mine will have a minimal impact upon the environment. When these decision makers explain how they’re going to issue a permit, and that permit will protect the river, land, plants, insects, animals, and my antiquity, my sacred area.

Will that permit bring comfort to my ancestors who have dwelt in that ground for time immemorial? Will that permit comfort the animals that will be displaced from their homes? Or the plants and insects? I don’t think so.

Who’s going to tell the whole of creation that calls this place home not to worry about the pollution? That the few jobs this mine will produce will be good for the communities living there? That somehow, this project will pull their respected communities out of their current economic crisis? They may not be able to enjoy the land, or drink the water, but at least they’ll have jobs…?

I was asked at a speaking event to introduce myself, and I said I was from the “Tribe of Barely Making It, but We’re Making It.” I would challenge any other group of people in America to endure what we First Nations endured, and be able to still hold on to their language and culture. We, First Nations people, are a part of this land, and our languages and cultures were born and bred here. We have always been here and we always will be. Our communities are abundant in strength and have determination to not give up; our old people taught us that. We will continue to resist colonialism for our next seven generations, so relatives in the future will understand that our languages and cultures will keep them grounded, determined and strong. We, First Nations, already underwent drastic climate changes and survived.

To whomever is reading this, as your eyes fall upon my last sentences, I want you, for a moment, to close your eyes and take a deep breath. Do you feel that? Do you feel the connection? Do you understand how sacred creation is? It’s made up from the same stuff as you and I are made of. We need to start to rebuild our relationship with our mother earth again. Let’s stand together and speak up for the voices who cannot speak for themselves, like the plants, animals, birds and insects. Let’s remember that we are a part of this land and not separate from it.

Let’s join our collective voices together and tell our leaders that we are no longer going to stay silent while our precious mother earth gets abused. Let’s tell them that we are going to reclaim our humanity and once again establish our connection with creation.

I’ll stand with all colors and creeds who value our mother earth and that have the courage to shoulder the responsibility that it’s going to take. I want to say waewaenon for taking the time out of your life to read this.

Anahkwet, also known as Guy Reiter, is a MENOMINEE NATION organizer and advocate.

My daily routine is nothing special; I wake up, turn on the tap to fill a glass of water and brush my teeth. On my way to work, I pass by Cherry Creek and the South Platte as I navigate Denver traffic. Throughout the day, I snack on fruits and vegetables to nourish my body, and as each day comes to a close, there is nothing I enjoy more than a chilled beer or glass of wine.

Besides the daily repetition, what else connects these different parts of my life?

Rivers.

Whether you realize it or not, rivers are entwined in nearly every aspect of our lives. So much of what we do, eat, wear, and use depend on rivers and the water flowing through them. There is a deep connection between our society and rivers, one that can be hard to comprehend. While enjoying rivers and water has long been a part of my identity, it wasn’t until college that I truly appreciated the complicated relationship and power that rivers hold on me.

Growing up along Lake Michigan, water never seemed scarce; it was everywhere. After college, my journey to the western US changed my perspective. I saw and began to realize the difference between managing abundant water versus managing water limited by scarcity. Here in Colorado and throughout the Colorado River Basin, our livelihood depends on these arteries – rivers – that crisscross the region supporting economic, social, and environmental values.

Annemarie Lewis, creator of our new podcast series, “We are Rivers: Conversations about the rivers that connect us.”

As a new way to spark a conversation about the value and complexity of rivers, American Rivers is excited to announce our new podcast series, “We are Rivers: Conversations about the rivers that connect us,” which can be heard through Soundcloud. Annemarie Lewis, this year’s Colorado River Basin intern, takes us on a journey to tell the stories of rivers and the important relationship they have with us. She explores the culture and history of the west and our nation by talking with adventurers, writers, water experts, and artists about their connection to rivers, and how they impact their lives.

The release of “We Are Rivers” coincides with Colorado River Day, a celebration of the hardest working river in America. The podcast series covers a wide array of topics across the Colorado Basin and other rivers in the west, including discussions around the Grand Canyon, the value of rivers, the Law of the River, and the future of Lake Powell.

Join us as we discover stories of success and challenges facing rivers across the west. Listen in today and subscribe to our podcast feed.

This guest blog by former Mayor Doug Oitzinger is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series on the Menominee River in Wisconsin and Michigan.

Forty-three years ago, I moved to the Marinette-Menominee area to take a job with Marinette Marine, a shipbuilder located on the Menominee River in the City of Marinette, Wisconsin. All this time I have lived either on the river or close to the bay of Green Bay into which the river empties. I can see the bay from my living room window right now. For 22 years, I worked at the shipyard on that river every day. I’ve also owned several small businesses in Marinette and was the Mayor of the City of Marinette for five years. While mayor, I served on the Wisconsin Coastal Management Council.

It is with this perspective that I see the proposed Back Forty Mine in Menominee County, Michigan, as threatening to undo forty years of river restoration in Marinette. For most of my residence in the area, the Menominee River was polluted with arsenic salts from a manufacturer that was located next to the shipyard. This pollution has been cleaned up only in the last few years with great expense to the company and to federal taxpayers. Finally, after all these years, our river is off the list of concerned waterways and fish can be eaten without a myriad of warnings about their consumption.

But that pollution existed in only a half-mile stretch of waterway in the city to the mouth of the river. The Back Forty Mine endangers more than thirty miles of river flowage until it reaches its mouth and empties into the bay. The mine’s contaminants are far more dangerous than the arsenic salts ever were! Building an open pit sulfide mine with its waste water holding pond fifty to one hundred feet from the river is insane. This isn’t a question of “if”; it’s a question of “when”— as in, “when something bad happens, what can we do”? And the answer is “nothing”.

There is only one way to fix a slurry of toxic waste from spilling into the Menominee River, and that is to never create the waste in the first place. To protect the river, protect our lifestyle, protect our property values, protect our health and our children’s health, to protect a growing tourist economy based on fishing and boating, and to protect our future, we must stop this mine from being built.

The Back Forty Mine owners tout the potential jobs and economic boost to the area. Their website explains that the maximum project length, which includes the reclamation period, is sixteen years. Any significant employment would accrue in a much shorter time period than the sixteen years. Those jobs will disappear in less than a decade. But toxic waste pollution isn’t like temporary employment; it can last for longer than anyone reading this will ever live.

Someone will get enormously rich from this mine if it is built, and it won’t be those of us living here. However, it will be us asking, “what do we do now,” when those toxins come racing down the river into our city’s front yard. Is less than sixteen years of employment for a few people worth risking thirty miles of the Menominee River perhaps forever? We are literally risking the well-being and economic security of forty thousand people in Marinette and Menominee Counties so a handful of people can be rich. This isn’t right. This isn’t smart, and this shouldn’t be allowed to happen.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/702/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

Doug is the former Mayor of Marinette, Wisconsin, and a long-time resident of the area.

Our family just spent a weekend on Oregon’s North Umpqua River. Watching my four year old play on the riverbank, I saw over and over again how rivers are the best playgrounds. The unstructured time for play, discovery, and relaxation reminded me that visiting a river is a great way to de-stress, get exercise, spend time together, and reconnect.

Make it a family tradition. Make it a habit. It’s fun, and you and your kids will be healthier and happier for it.

Here are five reasons why rivers are the best playgrounds:

Move and explore

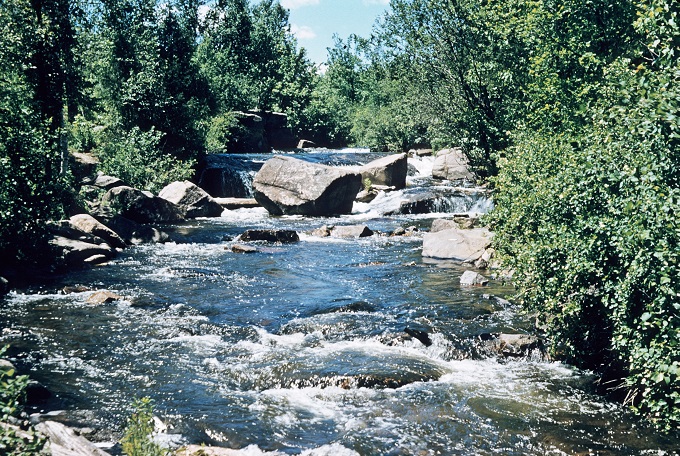

River and stream banks have everything a kid needs to move and play at his or her own pace and style: beaches, fallen trees and logs, and rocks. The Umpqua River has some great bedrock ledges, some smooth, some rutted, some with little potholes of rainwater. It’s a natural playground inspiring all kinds of motion –balancing on the mossy logs, climbing over and under branches, hopping around the bedrock, splashing in the puddles.

Make a friend

Typical playgrounds don’t have the variety of wildlife you can find on a river. We watched water striders in the calm shallows, and cheered at a duck as it paddled through a little rapid. We enjoyed the background chorus of birdsong and tried to guess which animals live in the little holes, caves, and cracks under rocks and logs.

Play with sticks

Kids love sticks. Dig with them, whack something with them, wave them around in the air. My little boy loves stick swords and we had some good ninja battles on the river bank. Driftwood chunks come in all shapes and sizes and are great for pretend play.

Learn

Where does all this water come from? Where is it going? We talked about how the river sculpts the banks and how it moves sand, gravel, even big boulders, downstream.

Dream

We all need beauty, something bigger than ourselves that captures our hearts and minds. Kids (and adults) need places where our imaginations are free to soar. Rivers give us all of this. Sit and watch the light dance on the water or hike to a waterfall.

Kids understand river magic.

This guest blog by Chairman Gary Besaw is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series on the Menominee River in Wisconsin and Michigan.

By now, a majority of the country and many around the world have heard of the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) and the resulting opposition to that project. The collective opposition to the DAPL was truly inspiring. Unfortunately, serious threats to water happen far too often, and many play out without the benefit of national and worldwide attention. One of these fights for clean water is happening right now on the Menominee River which separates Northern Wisconsin and Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. You may not have heard of the controversial proposed Back Forty mine yet, a project being pursued by a Canadian exploratory company named Aquila Resources, Inc., but you will and with your help thousands more will.

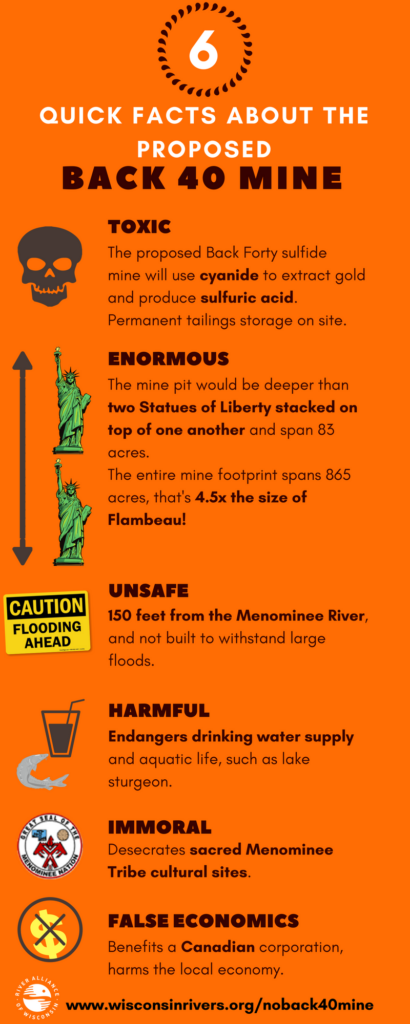

The Menominee River was recently named as one of America’s Most Endangered Rivers® due to the threats associated with the proposed Back Forty mine. The proposed project includes plans for a massive open pit metallic sulfide mine and processing facility located 50 yards from the Menominee River, a major Lake Michigan tributary and the largest watershed in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. The project poses significant risks to the clean water supply of communities near the mine site as well as down river and Lake Michigan communities. These communities are deeply reliant on the tourism and recreational industries which serve as an economic staple in the region. In addition, the surrounding ecosystem and sites of historic, cultural and religious significance to the Menominee Indian Tribe face the threat of destruction.

The project has received controversial approvals on three of the four permits required for the project, however the fight is far from over. The Menominee Indian Tribe and an adjoining landowner have challenged the mining permit approval. Additionally, review of the fourth permit, the wetlands permit, is just getting underway with a mounting opposition committed to the denial of the wetland permit.

An amazing side effect of the disastrous proposed Back Forty project is that it has awoken the collective spirits of people from all walks of life. As the public becomes more aware of the threats associated with this project, opposition to the project is quickly growing and includes tribal governments, national and regional tribal organizations, local city governments, local county governments, local township governments, national, regional and local environmental organizations, local citizen groups, local businesses, local fishing organizations, archeologists, and elected Wisconsin State officials. The widespread opposition across the social and political spectrum is telling of the dangers associated with the proposed project.

For the Menominee Indian Tribe, this project on the Menominee River, in Menominee County, MI, upriver from the City of Menominee, is deeply personal. The Menominee Indian Tribe is a federally recognized Indian Tribe, indigenous to the area. The Menominee Tribe’s place of origin exists within our 1836 Treaty area, at the mouth of the Menominee River. It was here that our five clans: Ancestral Bear, Eagle, Wolf, Moose, and Crane were transformed into human form and became the first Menominee thousands of years ago.

As a result of our undeniable ties to the Menominee River area, we have numerous sacred sites on the Menominee River, including the area of the proposed mine. These sites include burial mounds, places of worship, former village sites, and ancestral raised agricultural garden beds. Much like our brothers and sisters in the NODAPL movement, we also know that water is essential to life. The Menominee River is, after all, the very origin of life for the Menominee people. It also provides life to Michigan and Wisconsin residents and the natural wildlife within the Great Lakes ecosystem.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/702/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

The Menominee Indian Tribe’s rich culture, history, and residency in the area now known as the State of Wisconsin, and parts of the States of Michigan and Illinois, dates back 10,000 years. The Tribe’s members enjoy pristine lakes, rivers, and streams, over 219,000 acres of the richest forests in the Nation, and an abundance of plant and animal life.

This guest blog by Charlie Piette is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series on the Menominee River in Wisconsin and Michigan.

I’ll be very forward in expressing my opposition to Back 40—a proposed open pit sulfide mine on the Menominee River in Michigan—and yes, I’m tremendously biased. As a fly fishing guide, I have the pleasure of spending a significant portion of my time working on the Menominee River. I also happen to have a Masters of Environmental Science and Policy that focused specifically on water quality. Needless to say, those two facets combined make me extremely concerned for the future of the river if Back 40 becomes reality.

One of the most famous American fly fishermen described the Menominee as, “…the best smallmouth bass river that no one knows about.” I would whole-heartedly agree with this statement, but it is so much more than just a great place to fish. In the post-dam era, the river is in as pristine of a state as it will ever be. It supports a highly diverse community of native fishes, insects, plants, and birds, all of which depend exclusively on the clean water to thrive. Even a slight alteration of the present water chemistry caused by the Back 40 mine would have unknown, and quite possibly, devastating effects on the flora and fauna of the lower Menominee all the way out into Green Bay.

Aquila Resources, the proposed operator, paints an all-too-rosy picture of the life and final capping of the mine. Back 40’s engineering would be largely designed after another sulfide mine in Northwestern Wisconsin on the banks of the Flambeau River. Aquila and its associated designers are attempting to compare the two sights and highlight the Flambeau Mine as a success story with minimal water contamination. One doesn’t have to dig too deeply to determine that these two projects are completely different and have zero ground for comparison. First and foremost, the Flambeau Mine is a tiny fraction of the size that Back 40 would be. The waste rock generated by Back 40 would be nearly six times larger. Furthermore, unlike the Flambeau Mine, which shipped all its rock away for processing, Back 40 would exclusively process and store the toxic end products in the pit a mere 150 feet from the river.

Though there are many, two particular factors at play keep me awake at night. One is the dramatic change in weather here in the Upper Midwest. Whether or not you believe in climate change makes no difference in this instance. Pooling from well over one thousand days on the Menominee River over the course of 16 years, our staff would unanimously agree that the instances of severe weather events are increasing dramatically. 2017 has been a perfect example of this shift. We were forced to cancel more guide trips in the month of June than we have in the entire existence of our business combined, all due to the fact that the river was at or above USGS flood stage on several separate occasions. In 2016, Northwestern Wisconsin experienced one of the worst flood events on record. Considering the current frequency of severe weather, a similar event occurring along the Menominee seems more possible than ever. Despite Aquila’s lofty claims about its barrier wall containment capabilities, they are only held accountable by permit to build for a 100 year flood.

My second major concern is Back 40’s already granted National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit. It is the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) standard for effluent wastewater being dumped into a water body. As a graduate student, I managed an enormous data set containing pollutant concentration measurements from pollution point sources all across the Great Lakes. This data set was then used, in conjunction with the EPA, to determine if individual sources were in violation of their permits. My experience with this data taught me that many facilities often violated their NPDES permit with limited consequences that came to fruition long after the fact. Back 40 would be pumping treated waste water directly into the Menominee. What if they slip up in the treatment process? Or, what if the financial implications of violating their permit are insignificant compared to the profit while operating outside the law?

I had a simple, yet eye-opening experience this summer. It was a beautiful day and I saw a young family out floating down the river. They weren’t fishing. They were just enjoying a float in a beautiful, wild place. This, at the root of it all, is why it’s so important that Back 40 never becomes a reality. The risks are simply too great. The Menominee River, though largely unknown to many, is one of the most spectacular publicly accessible river ways in the country. I truly hope it remains that way so that anyone in the future can enjoy what we have today.

Please join us in asking the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality to reject the pending wetlands permit and prevent the establishment of the proposed Back Forty mine.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/702/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

Charlie is the Shop Manager for Tight Lines Fly Fishing Company, Northeastern Wisconsin’s largest fly shop. Charlie’s desire to help others progress as fly anglers is his driving force. Whether it’s through guided trips, classes, or daily interactions in the shop, he loves ensuring that others are more successful on the water.

This guest blog by Bill Hines is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series on the Neuse River and the Cape Fear River in North Carolina.

I’ve always felt the need to be close to the water. I think it comes from my being born into the Navy and being stationed on the water much of my young life.

We spent a long time searching the Atlantic coastline for the ideal place to retire and found Oriental, North Carolina, at the mouth of the Neuse River over 20 years ago. After moving here, the first thing I did was volunteer with the Neuse Riverkeeper Foundation.

I thought I could best help the Foundation and the river by sharing an up close experience on the river with others. With a village full of sailors, I felt it was important to get people even closer to the water – to get their elbows dipping in it.

When you are paddling on the water, you have an immediate concern for the quality of the water. You can start to see the complex interaction between the trees, marsh grasses, aquatic grasses, fish, and birds. All of these pieces need to work together in a balance in order to give us the enjoyment we receive from the various uses that people have for the water.

I enjoy the early morning paddle where I can watch the mist rise from the water, slowly revealing the possibilities for that new day. I like going out for full-moon paddles to watch the sunset and then see the moon rise. Exploring the creeks that make up the estuary marshes in Pamlico County gives a constant sense of adventure with a new view or experience around every bend.

I also enjoy birding along the water with the ever-changing rich variety of birds. We have an “Adopt a Duck” program where some of the local birders donate money for corn that I spread along the waterfront in the winter so that the diving ducks come in close for easy viewing.

I became concerned about our river when I spoke with the local fishermen, both commercial and recreational, and heard of flounder and other fish becoming scarce.

One night we were watching a satellite launch from the waterfront on a beautiful star lit night when we noticed the smell of sewage sludge floating by from Slocum Creek and Cherry Point Marine Air Station on the far side of the river.

On my annual paddles down the river from Raleigh, I am in awe of the beauty of the river, but occasionally am reminded of how waste from hog farms runs into the river when I smell it.

The Neuse is our treasure and one we need to work every day to protect.

Please join us in asking the Commissioner of the N.C. Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Steve Troxler, to champion the protection of this vital natural resource by pushing for full funding of the floodplain buyout program.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/1257/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

Author: Bill Hines

Bill is an accomplished paddler who patrols every week with a group of kayaking enthusiasts and bird watchers, picking up trash, monitoring the health of the rivers and creeks, and appreciating nature. He is an advocate, ambassador, and agitator for action on the Lower Neuse River. Bill wrote the chapter on paddling the Neuse River– see Friends of the Mountains to Sea Trail Guide, section 11A-16A Paddling the Neuse River– which he wrote from his own experiences paddling the entire length of the river.

Bill is an accomplished paddler who patrols every week with a group of kayaking enthusiasts and bird watchers, picking up trash, monitoring the health of the rivers and creeks, and appreciating nature. He is an advocate, ambassador, and agitator for action on the Lower Neuse River. Bill wrote the chapter on paddling the Neuse River– see Friends of the Mountains to Sea Trail Guide, section 11A-16A Paddling the Neuse River– which he wrote from his own experiences paddling the entire length of the river.

July is upon us here in the Colorado Basin, and things are hot! Aside from the scorching heat across the American Southwest (a record 119 degrees in Phoenix on June 19) a number of Colorado River-related stories have made their way to front pages in the past few weeks as well.

Rising temperatures inspired a recent report by Brad Udall (Colorado State University) and Jonathan Overpeck (University of Arizona) which indicates that the prolonged drought and rising temperatures have not only made it feel hotter, but have actually reduced the amount of water in the Colorado Basin by nearly 20% compared to flows between 1906 and 1999. This is dramatic as we deal with and address the substantial overuse of Colorado River water in the lower basin states of California, Arizona, and Nevada.

And even though the Upper Basin states of Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming saw an above average snowpack in early 2017, a dry March across the basin combined with these elevated spring temperatures has resulted in the US Bureau of Reclamation refining their projections of ample spring flows heading towards Lake Powell (and further benefitting Lake Mead) downward. So instead of a substantial improvement in both of these large reservoirs, the resulting conditions will be average at best. Further, the Bureau has also downgraded the projection of flows into Lake Mead in 2018 by more than 20 feet, increasing the risk of substantial cutbacks for the state of Arizona in the coming years. In short, even though we had a hopeful, wet spring, we owe it to the river to continue to work towards conservation every day, as we are truly all in this mission together!

Yampa River meanders through Yampa Valley agricultural fields en route to Dinosaur National Monument and the Green River. | Photo: Sinjin Eberle

All of this has created a discussion about how to think about stabilizing the Colorado River, from the headwaters deep in the Colorado mountains, all the way to the border with Mexico. Seven states, over 1,400 miles, affecting more than 35 million people and supporting a $1.4 trillion economy. First and foremost, American Rivers is working with partners across the basin to inspire ways to increase flexibility and keep more water flowing down the Colorado River from source to (ideally) sea. By collaborating with farmers and ranchers, municipalities, and water agencies, we are making headway in not only sustaining the river, but the people who depend on it as well. And our work has garnered further confidence from donors, foundations, and individual supporters like you who support our mission to protect wild rivers, restore damaged rivers, and conserve clean water for people and nature across the country. Without you, we could not continue our efforts to stabilize the Colorado River and sustain it for future generations to come.