This past winter, California received record precipitation following five long years of drought. Central Valley rivers, especially the San Joaquin, saw water levels not seen in nearly a decade, putting a deteriorating flood control system to the test. Luckily, there were no catastrophic levee failures, but there were several smaller breaches and plenty of erosion throughout the system, including along several tributaries. It was also a chance to see how new flood management approaches would perform under persistent flood conditions.

Over the last decade, American Rivers and many other conservation nonprofits have been working together with state agencies, levee districts, and farmers to reshape the flood management paradigm in America’s bread basket – California’s Central Valley. “Multi-Benefit Flood Management,” as it is being called, relies on using nature-based solutions such as restoring and reconnecting floodplains to reduce flood risk while also providing additional benefits like habitat for endangered fish and wildlife, recreational opportunities, and groundwater recharge.

This approach is not really new though – California’s system of flood bypasses are an example of one type of multi-benefit flood management. The Yolo Bypass takes diverted flood water from the Sacramento River and spreads it out over 60,000 acres of floodplain and farm land to the West of Sacramento. This protects the city and its inhabitants and also provides critical floodplain habitat for threatened fish and wildlife. And in years that it doesn’t flood, its rich soils are farmed, much of it in rice production. Reconnecting and restoring floodplains that are directly connected to rivers (unlike flood bypasses), like American River’s project at Great Valley Grasslands State Park along the San Joaquin River, are another way to achieve multiple benefits while reducing flood risk.

American Rivers, funded by the Wildlife Conservation Society’s Climate Adaptation Fund, is working to help the California Department of Water Resources (DWR) improve and expand the Yolo Bypass to provide more frequent inundation of this critical floodplain habitat while reducing flood risk for Sacramento and other downstream communities. As part of this grant, American Rivers is also conducting an outreach campaign to help promote multi-benefit flood management and floodplain restoration throughout the Central Valley. We realized that high quality compelling imagery of completed projects, projects in planning stages, and floodplains in action were missing from our campaign. So we tasked ourselves with creating an image archive that could be used indefinitely by us and our partners for advocacy and outreach for years to come.

In order to document conditions along the San Joaquin River following an epic winter and collect stock imagery of the San Joaquin River for the image archive, American Rivers teamed up with LightHawk, a nonprofit that accelerates conservation through the powerful perspective of flight. Pilots volunteer their planes and time to fly missions that create new imagery, collect data, or inform the public about some of our environment’s most pressing issues. This work could not have been done without LightHawk and their volunteer pilots, who fill a critical gap that is often hard to fund.

Back in June, I met up with Bill Rush, one of LightHawk’s dedicated volunteer pilots, for a flight along the San Joaquin River. Bill lives in the Santa Cruz mountains and volunteers for LightHawk, Flying Doctors, and Baja Communidad. As a photographer, I knew I couldn’t pass up this opportunity even though I have a fear of flying. During the 2-hour flight, we followed the river from Stockton to Mendota and back up again. Luckily, the pilot’s many years of experience, combined with the fact that I was intently focused on what was 2,000 feet below me, resulted in a smooth and productive flight.

Though it was June, the river was still relatively high (around 5,000 cubic feet per second) – high enough to see a few activated floodplains, but low enough to see impacts from the high flows that were endured for many months. Smaller levee breaches were clear in some areas (notice the beautiful sand patterns on farm fields in some of the photos), and other areas were still green and vibrant even though it was nearing mid-summer. I was also able to document several completed floodplain restoration projects and ones in planning stages that are being led by American Rivers and its partners. Overall, the flight provided invaluable imagery and data on the San Joaquin River after one of the wettest winters in recent years.

Given projected impacts to rivers due to climate change – increased frequency of wetter winters and drier summers – the imperative for more resilient approaches to water and flood management are more important than ever. By working with nature, instead of against it, we can improve the resiliency of California’s water infrastructure to more extreme floods and droughts.

[metaslider id=39413]

The enormous human tragedy unfolding in Texas, as a result of Hurricane Harvey, is a reminder that communities all over the United State are vulnerable to catastrophe when extreme weather events hit. As the nation rallies to help the people of Houston and the Gulf Coast recover, we should also prepare in our own homes and communities to make sure that we are ready for the next big storm.

Hurricanes and extreme floods are natural phenomena, but they can become human tragedies and economic disasters when we fail to prepare. Fortunately, we have new experience demonstrating how innovative flood management can gives us more tools to meet this challenge.

In California, American Rivers has been working with the state of California to develop a new flood plan for the Central Valley. In August, the Central Valley Flood Protection Board adopted that new plan, which will help protect more than a million people from devastating floods. Additionally, beyond providing for critical public safety, it will help restore the region’s rivers, fish and wildlife and groundwater supplies. By creating new parks and trails, it will also enrich the lives of Californians. More on that plan, below.

Major floods are becoming more common

The first step in preparing for extreme floods is confronting the risk. That risk is easy to overlook. After all, the odds of an extreme storm might be less than one percent in a single year. Your community could go many decades without seeing one. But, eventually, as in the case of the Gulf Coast today, an extreme storm will arrive. In addition, climate change is increasing the flood risk communities face. Confronting floods is one of the keys to making sure that our communities and natural resources will be resilient as our climate warms.

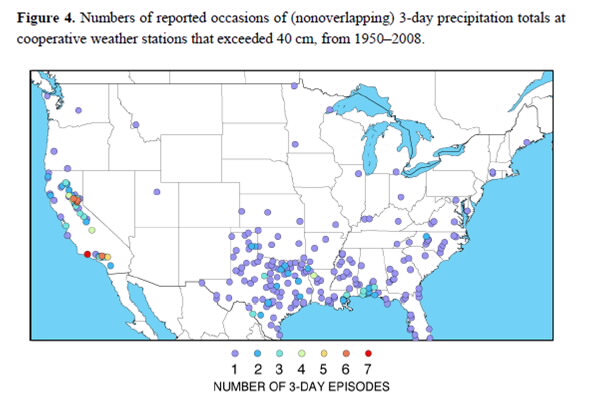

California and the Gulf Coast are both uniquely vulnerable to extreme precipitation events. Although the 50 inches Harvey dumped this week is setting a national record for totals over a single week, California has even more frequent high precipitation totals over three day periods. The following map from a scientific article about atmospheric rivers in the journal “Water” shows how California and the Gulf Coast both stand out when it comes to extreme precipitation.

Atmospheric rivers are jets containing staggering quantities of moisture from the tropics that periodically drench California and account for most of our floods and water supply. The great flood of 1862, which destroyed 1/3 of the taxable property in California, was almost certainly caused by an atmospheric river. A few years ago, the USGS attempted to simulate what might happen if we were struck with a similar ARk storm (Atmospheric River 1,000 year event) today and concluded that the resulting flood would displace 1.5 million people and cause flood damages totaling a whopping $725 billion.

If you are thinking that a 1,000 year event is too improbable to worry about, think again. There is evidence of six storms in the geologic record over the last 1,800 years that are larger then the flood of 1862. We are overdue. In addition, climate change could increases the risk we face, if more of the precipitation falls as rain rather than snow at the higher elevations of the Sierra Nevada.

For a quick read about the flood of 1862, ARk storms and the new Central Valley Flood Management Plan, check out the recent story and editorial in the Sacramento Bee.

Flood protection solutions in California

The scale of the risk is daunting. Fortunately, the new flood plan provides a road map to prepare for future floods in California’s Central Valley, which earlier settlers described as an Inland Sea. Giving rivers more room is the best way to keep communities safe from floods, and giving rivers more room provides multiple-benefits like clean water, parks and open space, groundwater recharge, and fish and wildlife habitat.

California’s new plan calls for expanding floodways and creating a new flood bypass at Paradise Cut on the Lower San Joaquin River to protect the rapidly urbanizing areas of Stockton, Lathrop, and Manteca. This new bypass will lower peak flood stage along 30 miles of river with a peak stage reduction of 2.5 feet at the I-5 Bridge, where thousands of new homes have recently been built. American Rivers led the design process and is leading the way to acquire the flood easements from private landowners that will be necessary to build the bypass. We have already obtained $4 million from the California Delta Conservancy and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife to buy flood and conservation easements for the new bypass. We are also helping the California Department of Water Resources expand the Yolo Bypass to better protect Sacramento. That expansion will aid the recovery of salmon runs on the most important salmon migratory corridor on the West Coast south of the Columbia River.

Multi-benefit flood management

The new flood plan calls for prioritizing multi-benefit flood management projects that are designed to reduce flood risk and enhance fish and wildlife habitat. Those projects can also create additional public benefits such as sustaining agricultural production, improving water quality and water supply reliability, increasing groundwater recharge, and providing public recreation and educational opportunities.

For struggling fish and wildlife, the news that smart flood projects can help fight the impacts of climate change is welcome. Salmon are a cold water fish. A warming climate stresses salmon and many other species. But multi-benefit flood projects help salmon and other natural resources in many ways. These projects create riparian and wetland habitat, and increased floodplain habitat that is well known for producing larger, healthier juvenile salmon. By allowing more water to pass safely, these projects can allow upstream dam operators to hold more water in reservoirs. More stored water means more cold water at the bottom of the reservoir. This cold water can literally be the different between life and death for salmon eggs and juveniles during the warm months of late summer and early fall.

Some of the many benefits of these new flood projects aren’t obvious at first glance. But among those benefits is a chance to make our rivers, fish, and wildlife more resilient in a warmer future.

Projects underway in California

Thanks to funding provided by the voters and directed by the legislature, over a dozen multi-benefit projects are already in the design and construction phase. These include:

- Breaching the levee at the San Joaquin River National Wildlife Refuge to reconnect 3,000 acres of floodplain.

- Restoring 2,000 acres of riparian and floodplain habitat at the Dos Rios Ranch across the river from SJRNWR.

- Removing a levee to restore 220 acres of floodplain habitat for salmon at Great Valley Grasslands State Park.

- Reconnecting the Oroville Wildlife Area to the Feather River to create rearing habitat for juvenile salmon.

- Setting back 7 miles of levee on the upper Sacramento River to reconnect 1,400 acres of floodplain and improve flood protection for Hamilton City.

- Expanding the floodway on the upper San Joaquin River to provide 100-year protection for the City of Firebaugh along with wildlife habitat and recreational opportunities for an economically disadvantaged community.

The Southport Project in the City of West Sacramento is one of the most exciting and ambitious multi-benefit flood management projects moving forward in the Central Valley. West Sacramento has a population of 52,000 people and is situated on the west side of an urbanized reach of the Sacramento River that is severely constrained by levees. The project is necessary to provide 100-year protection for the established and growing urban center. The project will set-back 5.6 miles of levee creating a new floodplain area 400 to 1,000 feet wide, creating 200 acres of forested wetlands in the heart of the Sacramento metropolitan area. A riverside trail will allow people to enjoy the riverside forest and access the river along the six mile long project, which will ultimately provide high quality habitat for several native species including juvenile rearing habitat for endangered Chinook salmon.

Smart solutions, safer communities

California is leading the way in responding to extreme floods and climate change related flood risks, both by adopting a plan founded in modern flood management, and by building multi-benefit projects on the ground. The broad benefits of this new approach explains why the new flood plan and multi-benefit projects enjoy extraordinarily broad support among California’s agricultural, flood agency, environmental, fishing and scientific stakeholders.

Thanks to the California Department of Water Resources, the Central Valley Flood Protection Board, American Rivers and many other government agencies and conservation organizations, California is preparing for floods in a way that will not only respond to a warming climate and reduce damage when the ARk storm arrives, but will also improve the quality of life for fish, wildlife, and people.

The National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) is not just an insurance program – it is a comprehensive flood risk management program that maps floodplains, issues hazard mitigation grants, and helps community’s implement safe local floodplain ordinances. American Rivers has great interest in the NFIP because it communicates flood risk and promotes community practices to mitigate that flood risk. Strong awareness tools combined with smart and safe floodplain management practices can help guide communities towards less risky development, and result in floodplains that have more room for rivers to safely flood.

Mapping

The NFIP communicates flood risk to communities through its Flood Insurance Rate Maps (FIRMs) produced by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). These maps are essential to implementing the NFIP as they indicate where the 100-year (1% annual chance) flood elevation resides. If your community is enrolled in the NFIP and you purchase a home within the 100-year flood elevation you will be required to obtain flood insurance. The trigger of having to purchase flood insurance ensures a property owner knows they will be living in a floodplain, and informs them of their flood risk. The cost of an individual flood insurance policy is defined by where a property is mapped in a community’s FIRM. Thus, the accuracy of these maps is vital to communicating actual risk to communities.

The term 100-year flood is confusing to many people because it refers to a flood that can happen more often than once every 100 years. Naming it the “100-year flood zone” can convey a false sense of security. In reality the 100-year flood actually describes a certain size flood that has a 1% chance of occurring in any given year, and the 100-year flood level is different for each stream and river.

Restrict Development

For a community to enroll in the NFIP they must adopt local zoning and building codes that guide development away from flood-prone areas. Restrictive zoning and flood-proofing building codes in flood-prone areas are mitigation techniques that help to protect a community from flood damage.

Mitigation

American Rivers believes the best way to reduce loss of life and property due to floods is to invest in mitigation before a flood occurs. Mitigation techniques such as relocating flood prone properties, conserving greenspace, and restoring floodplains and wetlands, can remove the threat of flooding to people and property. Communities that invest in mitigation experience less severe impacts and recover more quickly, becoming more resilient to the next flood event.

The NFIP is up for reauthorization at the end of September. Congress must pass this important piece of legislation in order to help communities become more resistant to floods. American Rivers would like to see some reforms in the program including:

- More accurate, current, and accessible mapping based on the best available science and technology (including climate science)

- Improvements to NFIP mitigation programs that will improve resilience

- Incentives for communities to enforce strong local floodplain management, with a focus on using nature-based approaches to flood mitigation

- Increased transparency on property flood history and changes to NFIP rates

Through these reforms, the NFIP can better protect people and property, and support the health of the environment by providing rivers the room to flood safely.

As the people of Houston struggle to recover from Hurricane Harvey, people all across America should consider contributing to the recovery effort and preparing for a flood in their own communities. American Rivers offers a few facts about floods to help people and communities prepare.

1. Floods are the most common natural hazards in the United States.

In terms of number of lives lost and property damage, flooding is the most common natural hazard. Floods can occur at any time of the year, in any part of the country, and at any time of the day or night. While heavy precipitation is the common cause of flooding, hurricanes, winter storms, and snowmelt are common, but often overlooked, causes of flooding.

2. Floodplains provide roughly 25 percent of all land-based ecosystem service benefits yet they represent just 2 percent of Earth’s land surface.

Floodplains are the low lying areas that surround rivers and other water bodies that naturally flood on a frequent basis. Naturally frequent flooding makes floodplains the “lifeblood” to surrounding areas. They provide clean water and wildlife habitat among many other benefits including one of the most visible functions, the ability to store large volumes of flood water and slowly release these waters over time.

3. Wetlands in the U.S. save more than $30 billion in annual flood damage repair costs.

Wetlands act as natural sponges, storing and slowly releasing floodwaters after peak flood flows have passed. A single acre of wetland, saturated to a depth of one foot, will retain 330,000 gallons of water – enough to flood thirteen average-sized homes thigh-deep.

4. Over the past century, we have experienced more intense and frequent storms.

Over the last 50 years, Americans have seen a 20% increase in the heaviest downpours. With a changing climate, we know that the size of the nation’s floodplains will grow by 40 to 45% over the next 90 years, putting more people in harm’s way.

5. In 2011 alone, there were 58 Federal flood disaster declarations, covering 33 different states.

The 2011 flooding damages cost over $8 billion and caused 113 deaths, both exceeded the 30–year averages.

6. The federal government provides flood insurance to homeowners, but the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) is $25 billion in debt to federal taxpayers because premiums are not keeping pace with the increasing risk of floods.

Claims have increased significantly over the last 15 years due in large part from Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy, and Hurricane Harvey will certainly increase the overall NFIP debt. Most homeowners at risk of flooding don’t have flood insurance and are thus at the mercy of disaster assistance, which costs taxpayers billions of dollars per year in addition to claims paid by the NFIP.

7. Roughly 17% of all the urban land in the United States is located in the “100-year” or high risk flood zone.

If you live in a high-risk area and you have a federally backed mortgage, you must buy flood insurance. Flood insurance costs vary, but the average cost is $550 per year. If your community participates in FEMA’s voluntary Community Rating System (CRS), you can save up to 45% on your insurance premium. If you live near the 100-year floodplain, you should seriously consider purchasing flood insurance.

8. Over the course of a 30 year mortgage, homeowners in the 100-year floodplain have a 1 in 4 chance or greater of being flooded – twice the probability of fire damage.

Floods are not limited to the 100-year floodplain and 100 year floods can happen more frequently than once every century. Over 20% of the flood insurance claims and one-third of all flood disaster assistance is for flood damage outside the 100-year floodplain. The concept of a 100-year flood is a statistical projection that refers to the flood event that has a 1 percent probability of occurring in each and every year. As the climate changes, the size and area subject to the 100-year flood will increase.

9. Flood mitigation practices that reduce the loss of life and damages to properties provide $5 in benefits for every dollar invested.

When homeowners and communities take steps to protect themselves and to reduce the impacts of flooding through mitigation practices such as elevating or flood-proofing their homes, moving flood prone structures out of harm’s way, and investing in “natural defenses” they can save themselves and taxpayer’s money because it’s less expensive to prepare for a flood than it is to keep cleaning up afterwards.

10. Levees can and do fail often with catastrophic consequences.

An estimated 100,000 miles of levees crisscross the nation. There is no definitive record on the exact number or the condition of those levees. We do know that over 40 percent of the U.S. population lives in counties with levees and that many of these levees were designed decades ago for agricultural purposes but now have homes and businesses behind them. Setting back levees to give rivers more room to safely carry flood waters is often the best way to protect communities from catastrophic floods. Giving rivers more room provides other benefits such as clean water, parks, and wildlife habitat.

Unprecedented flooding from Hurricane Harvey

News reports have called the impacts of Hurricane Harvey “catastrophic” and “apocalyptic.” According to the National Weather Service, “This event is unprecedented and all impacts are unknown and beyond anything experienced.”

The Weather Channel says Harvey “may end up being one of the worst flood disasters in U.S. history.”

The devastation from Hurricane Harvey will be far-reaching and will have long-term impacts for the region, and our nation. At American Rivers, our thoughts are with all of the victims of this disaster. Lives will be forever changed by this historic flood. The relief workers, first responders and volunteers who are risking their lives to help those in need deserve our deepest gratitude.

Hurricane Harvey has been especially devastating for a number of reasons, and climate change is one. Climate change amplifies storms. Warmer air can hold more moisture and warmer seas cause water to evaporate faster, which means more rainfall during storms—a key factor in Harvey’s extensive flooding.

Parts of Houston, Texas saw over two feet of rain in 24 hours. At least eight people have died, and on Sunday there was a two and a half hour wait for 911 assistance. At least nine trillion gallons of water have fallen on Texas, with an additional five to 10 trillion gallons to come over the week — up to 50 inches of rain, meaning some areas will get a year’s worth of rain in a week.

“Many textbooks have the 60-inch mark as a once-in-a-million-year recurrence interval, meaning that if any spots had that amount of rainfall, they would essentially be dealing with a once-in-a-million-year event,” writes Matthew Cappucci in the Washington Post.

Flood waters continue to rise. Many people are still trapped in their homes and rescue efforts continue.

Find out how you can help victims.

On June 27, 2017 Administrator Scott Pruitt of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced a roll back of an Obama-era administration policy that protected more than half the nation’s streams from pollution. “We are taking significant action to return power to the states and provide regulatory certainty to our nation’s farmers and businesses,” Pruitt said in a statement at the time. But what is the Clean Water Rule (CWR), why was it never implemented, and how will repealing it affect the drinking water of one in three Americans?

The Obama administration introduced the Clean Water Rule, also known as the Waters of the United States rule, in 2015. The regulation was meant to clarify portions of the 1972 Clean Water Act (CWA). The CWA explicitly protects the “waters of the United States,” which are defined under previous regulations as “traditional navigable waters, interstate waters, all other waters that could affect interstate or foreign commerce, impoundments of waters of the United States, tributaries, the territorial seas, and adjacent wetlands.”

However, under the CWA, it was difficult to discern if certain bodies of water were federally protected or not. Were wetlands adjacent to non-navigable tributaries of navigable waters protected or not? Confusing, right? These uncertainties lead to frustrations between developers and environmental protection groups, and ultimately, were addressed several times by the U.S. Supreme Court.

On May 27, 2015, the EPA and the Army Corps of Engineers released the CWR as a means to clarify the CWA. The rule maintained much of the old definition of the “Waters of the United States,” but took into account past Supreme Court rulings, public comment, as well as a major scientific assessment known as the Connectivity of Streams and Wetlands to Downstream Water Assessment. This assessment concluded that “streams, regardless of their size or how frequently they flow, are connected to and have important effects on downstream waters.” Naturally, large bodies like lakes and rivers were listed, but the rule also found streams (intermittent and ephemeral ones too), ponds, and other smaller features that have connections to these bigger, “navigable” waterways are indeed federally protected.

Since October 2015, the Clean Water Rule has been stuck in federal appeals court. But just because the Rule hasn’t been fully implemented, doesn’t mean repealing it won’t have long-term effects on our drinking water, environment, economy, and much more.

According to the EPA, within the continental U.S., about 117 million people, or over one third of the total U.S. population, get some or all of their drinking water from public drinking water systems that rely at least in part on intermittent, ephemeral, or headwater streams. These are the same intermittent, ephemeral, or headwater streams that the Trump administration’s EPA wants to no longer protect by revoking the Clean Water Rule. By slashing clean water safeguards, the President and Pruitt are putting the health of hundreds of millions of us at risk.

Not only is our drinking water at risk, but clean water is essential to the economy. Our $887-billion outdoor recreation economy supports 7.6 million American jobs, and it all depends on clean water. In 2011 alone, hunters spent $34 billion, anglers spent $41.8 billion, and wildlife watchers spent $55 billion. The money that sportsmen spend in pursuit of their passion supports everything from major manufacturing industries to small businesses in communities across the country.

The streams and wetlands that the CWR protects not only affect the water quality for fish downstream, but also provides nesting habitat for more than 50% of North American waterfowl. Wetlands span some 110 million acres across the U.S., providing critical habitat for fish and wildlife as well as aiding in filtration of contaminated runoff and groundwater storage. If we lose these wetlands, we risk losing habitat for fish and wildlife and the economic boost given by those on the quest for the perfect catch.

What happens upstream, effects those downstream. What we do today to protect our water, protects our water tomorrow. It’s that simple.

We have until September 27th, join us in telling the EPA and Administrator Pruitt that we need to strengthen, not weaken, safeguards for clean water.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/1597/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

Guest post by Gloria Nichols is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Green-Toutle River.

Recently, I learned that the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and U.S. Forest Service are once again planning to issue permits to allow exploratory drilling along the Green-Toutle River.

My heart sank.

I am one of thousands of local citizens who have been fighting mining proposals in that area for over a decade, so this seemed like an enormous setback. When a previous mining company, General Moly, Inc., applied for a hardrock mining lease in the same area, over 30,000 people sent comments in opposition to what the company said would be a 4,000 to 6,000 acre open pit mine. Partly based on that public response, in 2008, the BLM denied the lease. We were elated!

Despite pubic opposition, federal agencies continue to consider harmful mining activities in this area. Ascot Resources, a Canadian company, applied for exploratory drilling permits in 2011. Although thousands of people wrote comments in opposition, the permits were granted. After having the permits overturned in court, the agencies may once again allow exploratory drilling in this pristine watershed.

Fortunately for my mental state, I found out that many citizens are working to find a way to permanently stop mining in the area.

Why am I, like so many others, opposed to mining in the Green River valley?

First, I am a resident of Kelso, Washington, a small town that in March 2016 passed a resolution against mining in the Green River valley area. We are 60 miles from the mining site, but we get our drinking water from the Cowlitz River, which is downstream from the Green-Toutle River. Mining along the Green River could be catastrophic to our water supply.

Hardrock mining in the Green River valley poses a high risk of acid mine drainage into the Green River. In the past, a small, unsuccessful silver mine within the proposed drilling area leaked acid mine drainage into local streams.

Mining on the edge of an active volcano adds even more risk of pollution. Mount St. Helens periodically produces swarms of hundreds of small earthquakes. Each tremor would eat away at the stability of a mine only 12 miles away from the crater—and risk a tailings pond breach that would pollute the watershed with toxic mining waste.

We “downstreamers” don’t want acid mine drainage or other mining waste in our watershed, especially our drinking water.

Second, the proposed mining site is a beautiful recreational area that literally touches the border of the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument. Many people fish, hunt, hike, and ride horses in this area. From the valley they can take trails up to views into the volcano’s crater or through an old-growth forest that was miraculously sheltered from the eruption. Any mine would destroy the recreational values within the Green River valley. It also infuriates me to think that a noisy, dusty mine could be visible from backcountry trails within the Monument, an experience that would certainly discourage visitors from using those trails.

In coming years, I want people to enjoy undisturbed all parts of the Monument and the Green River Valley. I want future generations to fish local rivers for salmon and steelhead trout and to have access to clean, inexpensive drinking water from the Cowlitz River.

Fortunately, there are ways to stop this mine. So, with my fellow citizens, I will keep battling for a permanent solution to protect this beautiful area and our watershed. Please join us!

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/711/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

Author: Gloria Nichols

Author: Gloria Nichols

Gloria Nichols is a resident of Kelso, Washington, a town that gets its water from the Cowlitz River.

Last month we released our new podcast series, We Are Rivers: Conversations about the Rivers the Connect Us. We are Rivers discusses just how important rivers are for each of us and the places we call home.

Here in Colorado River Basin, collaboration is becoming the new normal. The arid climate, growing populations, and climate change all impact the finite amount of water available for communities, nature, and the economy. From the upper to the lower basin, local communities, states, and two countries (the United States and Mexico) are banding together to determine the best, collaborative path forward to secure a clean water supply.

Last week we released “Turning Towards Solutions,” which builds upon our previous episode, “Law of the River.” Across the Colorado River Basin, collaboration, cooperation, and compromise between towns, districts, states, and basins is an increasingly relevant theme. “Turning Towards Solutions” explores how collaborative actions like the Drought Contingency Plan and Minute 319 (the pulse flow) are creating promise and opportunity for sustaining the Colorado River and the people and communities that depend on it.

Put on your headphones and tune in to hear about efforts to create a new pathway to preserve both this crucial resource, and the legacy of the entire southwest. Then join the conversation on Americanrivers.org.

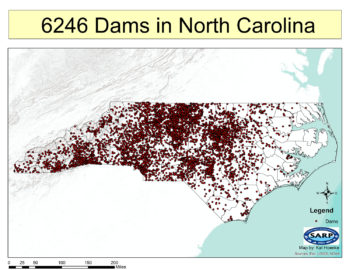

In North Carolina there are 6,250 dams blocking our rivers and streams – and this does not even include farm ponds. Most of these dams are no longer serving their intended purpose like powering old mills or pooling water for unneeded water supply. These obsolete relics clog rivers stopping fish from accessing their habitat, pose a public safety hazard, increase the threat of upstream flooding, and block recreational economic growth opportunities.

American Rivers has been working in North Carolina for more than a decade on various voluntary dam removal projects and have had great success. But the regulatory system in place in North Carolina – like many states across the country – is not designed to facilitate restoration; it is designed to stop pollution and destruction of the streams and rivers we love. Projects that are badly needed can be delayed and costs increased due to needing to push these restoration projects through a system that is looking for ways to stop damage rather than encouraging restoration.

In order to improve this system and encourage more dam removals, we have successfully worked with the North Carolina General Assembly and Department of Environmental Quality to write and pass a bill – SB 107: Streamline Dam Removal – that makes dam removal easier in the state. The bill was championed by state Senators Andy Wells (R-Hickory), Brent Jackson (R- Autryville), Rick Gunn (R-Burlington), and Mike Woodard (D- Durham) and Deputy Majority Leader Representative Stephen Ross (R- Burlington) and after unanimous approval by both the state House of Representatives and Senate, it was signed into law by Governor Roy Cooper on July 20th.

The new law begins to develop a system for dam removal in the state by:

- Creating an explicit state review under the Clean Water Act for dam removals;

- Focusing the limited resources of the State’s Dam Safety program where the most need is – high hazard dams where an uncontrolled breach would cause loss of life;

- Acknowledging that removing the dam restores the natural river ecosystem which does not need to be mitigated;

- Improving the state floodplain mapping requirements for dam removal; and

- Organizing a coordinated review by the Department of Environmental Quality and the Department of Public Safety (Floodplain Mapping) of the permitting system and the development of a report on how to best optimize dam removal regulation in North Carolina.

This bi-partisan effort was one of the very few pro-environmental bills to move through the North Carolina legislative process in 2017. It shows the breadth of support that river restoration through dam removal currently has in the state and the country.

American Rivers continues to propel the dam removal movement forward both by improving the process to make it easier for more NC dams to be removed (like with this bill) and by leading on-the-ground removal projects, such as the Shuford Dam on the Henry River, the multiple dams removed on the Haw River, or many others.

Smart Prioritization and Collaboration Critical

By: Sinjin Eberle, Director of Communications Intermountain West-American Rivers; Kristin Green, Water Advocate-Conservation Colorado; Rob Harris, Senior Staff Attorney-Western Resource Advocates; and Brian Jackson, Associate Director Stakeholder Projects-Environmental Defense Fund

Most everyone in Colorado knows that we can’t take a reliable water future for granted. Having clean, secure water for our communities, businesses, and agriculture, along with healthy rivers for respite, recreation, and to fuel our economy is not a given. In 2015, Colorado adopted a water plan, setting a course to achieve a reliable water future. Many applauded the balance of solutions and goals, including bolstering water conservation and reuse, looking for favorable ways to share water between cities and agriculture, and ensuring we had plans, and ideally actions, to keep our streams healthy.

Recently, the cost of the plan has come up in discussion.

There is no firmly identified cost to implement the water plan. We only have estimates at this time for what it will take to secure reliable water for our communities, agriculture, and environment. Those costs will become clearer as the state and water providers prioritize what water conservation, new supplies, water reuse, and stream restoration we want to do.

What we do know is that it will take resources to preserve the Colorado we love, and keep our farms productive and taps flowing. We also know that the resources we need to restore and protect our rivers and streams, and find innovative ways to conserve water, are currently underfunded.

The initial estimate for the plan put the cost of implementation around $20 billion. That estimate includes the cost of the projects proposed from each basin around the state, but given the state’s limited resources that number could change as stakeholders further prioritize those projects.

We recently heard a higher estimate of the costs of the plan that some might misconstrue. The reason why we should hold off on treating that higher estimate as a final price tag can be seen in a simple comparison: when a Colorado family needs a new car, most are not going to go out and buy a Ferrari when a Ford affordably meets their needs – and that’s what we have here. We can achieve all of what’s needed to secure Colorado’s water needs into the future while investing only in those ideas that provide the best return to ratepayers and taxpayers. That’s what Coloradoans expect and it can be done. We need to identify what projects are a priority and which are financially feasible. We need to make sure we don’t double count projects that overlap with each other.

We encourage the state to prioritize funding the most cost-effective and feasible projects to secure a reliable water supply and protect our rivers and streams. Water conservation is one of the most cost effective ways to get where we need to go. Other innovations like water reuse and agricultural-urban sharing can provide multiple benefits and help us achieve a reliable water future.

Do we need more money? Yes. There are water needs identified in the plan that will likely need new sources of dedicated funding. New funding sources should be used to support stabilizing a clean water supply for people, river health, agricultural conservation and efficiency, municipal conservation for smaller and medium-sized communities, and environmental water transactions. These projects are modest in costs, like adding air conditioning to a Ford, not a splurging on a lavish luxury car.

Collaboration will be critically important to shaping our water budget. We look forward to working with agriculture, water providers, businesses, consumers, the state, local leaders, and other stakeholders in exploring the best way to meet the goals of the Colorado Water Plan.

Guest post by Charles Miller is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Mobile Bay Basin.

In Bibb County, Alabama, down dirt roads and past stands of longleaf pine, runs a profoundly special stretch of the Cahaba River. It is a place that seems a world apart from the hustle and bustle of Birmingham, an hour’s drive to the north. This stretch of the river and the surrounding hills have a paradoxical combination that can be found in many natural places: perfect stillness and incredible motion. The shoals here continue the millions-of-years-old process of cutting water gaps through parallel ridges, while the summer’s hot air hangs motionless above.

The Cahaba is, in many ways, the last real river in the Mobile Bay Watershed; the only one that escaped the transformation into a series of reservoirs that the Coosa, Tallapoosa, Alabama, and Black Warrior rivers were subjected to in the early 20th Century. The Cahaba is a remnant of the astounding biodiversity once found throughout each and every river and stream of the Mobile Basin. This variety, now largely lost to the ages, still exists in other pockets as well, but as time (and human encroachment) march on, is becoming increasingly rare. Now only the hardiest endemic species cling to the niches they’ve adapted to over hundreds of thousands of years.

My personal feelings about the Cahaba stem from more than just its physical characteristics. It is to me, what countless of streams in countless of places across the country have been to Americans for years: it is my river. It is where I learned to swim and paddle. It is where I made the connection between the abstract science I was learning at the University of Alabama and the reality of the immense, dynamic processes through which rivers shape the land. When I have dreams about rivers, it is the Cahaba that I see, with lily-cloaked shoals the size of football fields under cerulean skies.

Unfortunately, without improved water management, these dreams may someday be all I, and other Alabamians, have left of the Cahaba as it exists today. Alabama is the only state in the region without a comprehensive water management plan, and the effects of that were demonstrated during a record drought last year. Reservoirs throughout the state reached record lows, and in many areas streams and creeks ran completely dry. Even rivers that did not dry up faced severe impacts from lower flow rates, leading to a degradation of water quality.

Canoers enjoying Alabama’s longest free-flowing river, the Cahaba, at Cahaba River National Wildlife Refuge. | Photo: Garry Tucker, USFWS

As droughts increase in frequency and severity, and demand for water continues to grow, Alabama must take charge of our water resources and our irreplaceable natural heritage. Without rules to regulate water withdrawals and protect instream flow, we run the risk of permanently damaging our state’s economy and its capacity to provide clean, affordable drinking water to its citizens.

Steps are being taken to move the state towards this necessary goal. In 2012, the Alabama Water Agencies Working Group (AWAWG) was convened to develop recommendations for a statewide water plan, and in 2017, they reported their findings to the governor. Unfortunately, Governor Kay Ivey has yet to release this report to the public.

In the 2017 Legislative Session, Rep. Patricia Todd introduced the Alabama Water Conservation and Security Act, which would have given the state government the authority to implement a comprehensive water management plan. Local, state, and national groups, including American Rivers and Alabama Rivers Alliance, continue to advocate for the release of the AWAWG report, as well as the adoption of a comprehensive water management plan. The hints of progress over the past few years are heartening, but in order to ensure the future of the river system E.O. Wilson called “America’s Amazon,” as well as the communities that it flows through, Alabama must step up to the plate and develop a plan to responsibly steward our water resources.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/712/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

Charles Miller is a nearly lifelong resident of the Alabama-Tallapoosa-Coosa River watershed. He recently graduated from The University of Alabama with a B.A. in Political Science and a minor in Geography. Growing up on Green Mountain in northern Alabama, he gained an appreciation for the importance of wildlands and open space, especially in urban and suburban areas. Charles enjoys traveling, hiking and photography. Charles is an AmeriCorps Alumni and serves on the Junior Board for the Alabama Rivers Alliance.

Guest post by Nicole Budine is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Green-Toutle River.

Since 2005, the Green-Toutle River in Washington State has been threatened by mining proposals. Mining activities in this valley, on the banks of the Green-Toutle River, could pollute these pristine waters, and would destroy the Green River valley as a place for solitude and backcountry recreation.

I first experienced the Green-Toutle River last October, when I visited the Green River valley with a small group to create the video below about this special place.

The beauty of the river and the valley exceeded my high expectations. Despite our concerns that the foggy weather would prevent us from seeing much of the valley, the fog lifted, exposing creeks cascading down the steep valley walls before joining the Green-Toutle River. Autumn in the valley is especially beautiful, with multi-colored shrubs in the blast-zone and yellow trees mingled with the evergreens. During my visit, it was easy to see why many people have worked hard to protect this river from a risky hardrock mine.

The Green-Toutle River begins in the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument before exiting the Monument’s borders to flow through the scenic Green River valley. In this valley, the river passes through a landscape shaped by the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens – with blast zone bordering patches of forest that escaped the eruption. The valley is only accessible by one, single lane forest road and surrounded by large roadless areas – making it a fantastic place for backcountry recreation activities such as hiking, backpacking, hunting, and horseback riding. The scenic beauty of the valley, its proximity to the Monument, and the immense recreation opportunities motivated the U.S. Forest Service to purchase some lands within the valley with funding from the Land and Water Conservation Fund. Some of the very same LWCF lands are now at risk of mining exploration and development.

The scenic valley bordering the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument is critical to the health of the Green-Toutle River. People enjoy the remote valley for backcountry recreation and solitude, but the valley has another important value – keeping the headwaters of the Green-Toutle River cool and clean. The wild landscape along much of the river helps to maintain high water quality for wild steelhead and drinking water for downstream communities.

The high water quality and unique ecological features of the Green River valley make the Green-Toutle River eligible for Wild and Scenic River designation. In addition to its beautiful vistas, recovery areas from the 1980 eruption provide unsurpassed opportunities for scientific interpretation of the effects of the eruption and natural restoration processes. They also provide unique habitats for a host of native species, including northern spotted owl and a growing population of elk.

Mining activities in this valley threaten water quality throughout the Green-Toutle River, and compromise the entire watershed. Thanks to the dedication of those who care deeply about this river, we have successfully prevented mining along the Green-Toutle River for over a decade. However, the U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management may once again allow a foreign mining company to conduct exploratory drilling along the banks of this treasured river. Exploratory drilling risks introducing pollutants into these pristine waters, and it is the first step toward developing a large open pit mine in the Green River valley. We must act now to stop the agencies from issuing these permits and urge them to protect this river long term. With your help, we are hopeful that future generations will be able to enjoy the Green-Toutle River’s clean waters and unique landscape.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/711/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

Author: Nicole Budine, Policy and Campaign Manager, Cascade Forest Conservancy

Author: Nicole Budine, Policy and Campaign Manager, Cascade Forest Conservancy

Nicole joined the Cascade Forest Conservancy in 2016. She grew up in upstate New York, cultivating her love of nature by exploring the local forests and rivers. Prior to joining the Cascade Forest Conservancy, she held roles doing policy and legal work for Trustees for Alaska and Oregon Wild. In her free time, Nicole enjoys painting, snowboarding, and exploring the northwest with her dog.