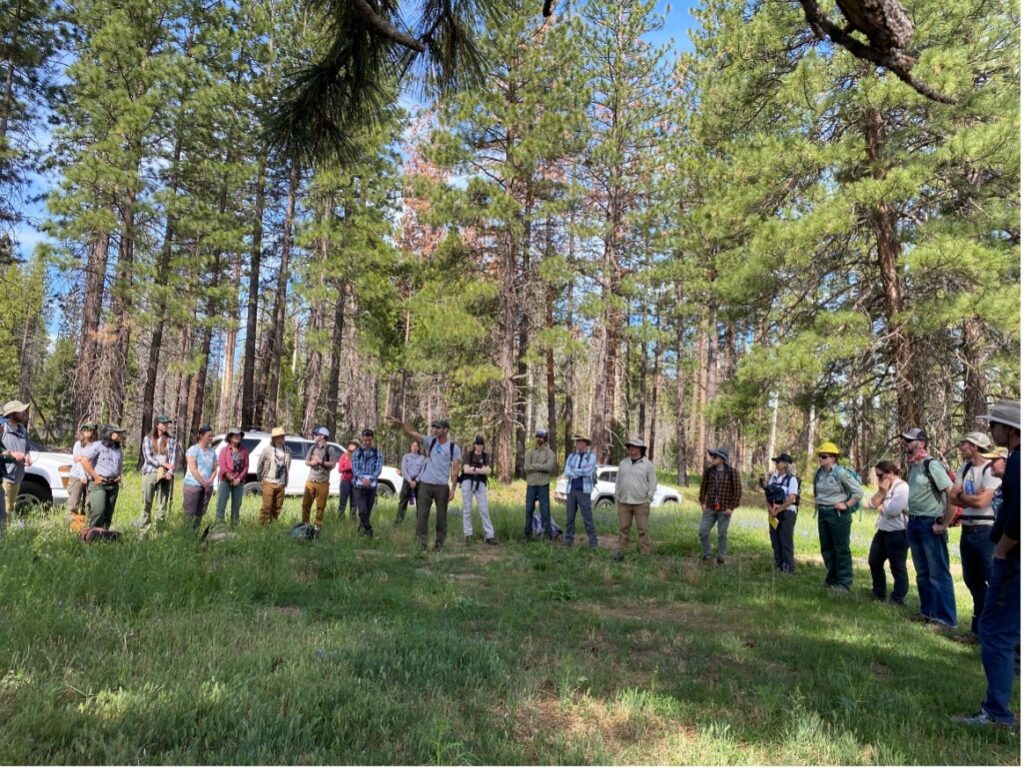

It’s just shy of 9 am on a warm June morning. Cars pull into a dirt pull-off in Yosemite National Park along a large meadow surrounded by granite peaks and the scars of the 2013 Rim Fire. People arrive and hug as they reunite with old friends and colleagues and introduce themselves to new ones. The Sierra Meadows Partnership’s annual meeting is about to begin at Ackerson Meadow.

The Sierra Meadows Partnership (SMP) is a regional collaborative group that works to improve the resources, support, and efficacy around meadow restoration in the Sierra Nevada. This June, the group members met for their first annual meeting in three years at Ackerson Meadow in Yosemite National Park and the Stanislaus National Forest. The plan: to tour Ackerson and learn about one of the largest meadow restoration projects in the Sierra Nevada.

Nearly 60 people attended this year’s SMP meeting. Affiliations included the National Park Service, US Forest Service, US Fish and Wildlife Service, nonprofit groups, state agencies, land trusts and conservancies, and more. The purpose of this field tour was not only to learn about the Ackerson Meadow Restoration Project, but also to build connections, network, brainstorm new projects, and strengthen partnerships to enhance meadow restoration across the Sierra

Ackerson meadow was this year’s field trip destination because the project is a unique example of how large-scale restoration projects are born from meaningful collaboration. The project is led by American Rivers, Yosemite National Park, and the Stanislaus National Forest, and supported by funding from the California Wildlife Conservation Board, donors of American Rivers, US Forest Service, Yosemite Conservancy, and Yosemite National Park.

Ackerson has a rich history that stretches back before the arrival of European settlers, to when the Central Sierra Miwok and Tuolumne Band of Me-Wuk Indian tribes would gather and use the abundant resources found in the area. It was homesteaded in the 19th century and a century of livestock grazing, ditch construction, and haying operations contributed to the meadow’s degradation. The meadow is substantial in size at 230 acres, with Yosemite style granite domes rising from the north. It is home to many rare and endangered plant and wildlife species including the Willow Flycatcher, Great Grey Owl, and slenderstem monkeyflower. Unfortunately, the combination of historic land uses at Ackerson resulted in massive ecological and hydrologic degradation, the centerpiece of which is a 3-mile-long gully, 15 feet deep and 100 feet wide, that drains this once vibrant wetland, robbing it of critical functions like groundwater storage, carbon sequestration, clean water supply, and wildlife habitat.

The restoration project at Ackerson is one of the largest meadow restoration projects attempted in the Sierra Nevada. The project includes filling the eroded gully with more than 150,000 cubic yards (15,000 dump trucks!) of soil and wood chips. This will allow the stream to spread across the meadow as it once did, rewatering 190 acres of lost or marginalized wetland habitats, improving water quality to the Tuolumne River system, increasing flood protections, and improving critical habitats for Ackerson’s diverse species.

The project embodies the goals and vision of the Sierra Meadows Partnership, which aims to restore 30,000 acres of Sierra Nevada meadows by 2030. The tour was alive with conversation and debate, while passionate attendees put their heads together in an idyllic setting. As the project leaders discussed the details of the restoration design, tour participants exchanged ideas about soil carbon, beaver dam analogs, and rare wildlife and vegetation in the area.

The SMP: Building Towards 30,000 Acres Together

In addition to being a resource group for partners interested in meadows across the Sierra Nevada, the SMP also conducts an annual survey of member organizations to track progress towards their overarching goal of restoring and protecting 30,000 acres of meadows by 2030. The surveys collect data on key metrics like total acreage, land ownership, restoration objectives and actions, target wildlife species, and projects completed every year.

In 2022, the SMP found that 89 projects, over 16,000 acres, have been completed or are in progress across the Sierra. Seventy of these projects, totaling 9,000 acres, are restoration projects—nine of which were completed in 2021, restoring nearly 400 acres. The others are part of conservation easement and research projects.

The US Forest Service is the primary landowner for meadow projects in the Sierra, almost half of these projects are happening on National Forest System lands. The National Park Service and private landowners also host a significant portion of meadow projects. Improving habitat for wildlife species is a key goal for most of these efforts and some of the most common target species include the Sierra Nevada yellow-legged frog, willow flycatcher, Greater Sandhill Crane, bald eagle, and various native trout species.

Tracking trends in restoration methods is another key part of the survey, and this year channel fill, infrastructure improvements, revegetation, and beaver dam analogs were some of the most common techniques used to bring meadows back to life. These projects were most often funded by the California’s Wildlife Conservation Board, California Department of Fish and Wildlife, and the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, all of which have grant funding programs focused on these critical habitats.

The SMP’s tracking report and events like the Ackerson field tour inspire members of the SMP to learn from one another and share knowledge and expertise to address the ecological health of the Sierra Nevada. As the practice of meadow restoration continues to grow and change with our climate, the SMP’s members continue to learn, adapting their efforts in a changing world to restore these important ecosystems. Meadows are integral to Sierra Nevada watersheds, wildlife, as well as water quality and by restoring them we are bettering our environments and communities.

After spending a day in a beautiful place like Ackerson meadow, with so many others who are passionate and dedicated to such important work in the Sierras, I felt inspired. Not only did I learn about the project and different meadow restoration practices, but I also felt hope for the great work that is happening and saw the passion, joy, and deep interest in all the efforts being made across the Sierras. After the tour finished and the dust settled, environmental advocates from across the state hopped back in their cars and returned home with new connections and new ideas. Partnerships are powerful when driven by a common purpose, and the Sierra Meadows Partnership exemplifies American Rivers’ collaborative and adaptive approach to restoration, reminding us that we are stronger when we work together.

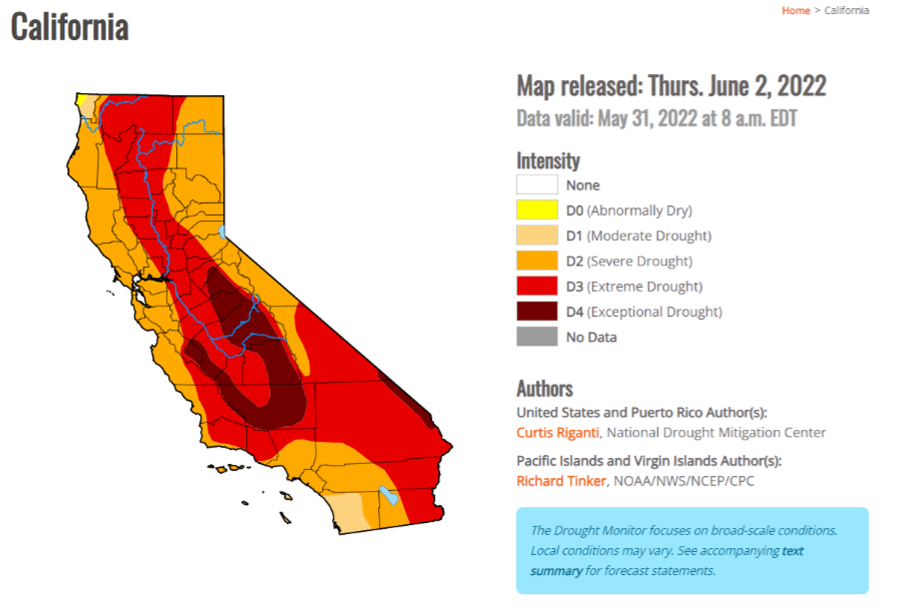

- With typically arid springs and summers, droughts are normal in California… but not at this intensity.

Climate change is intensifying drought across the state, which puts the state in a precarious position that compromises water supplies for drinking and agriculture, increases wildfire risk, and threatens fish and wildlife. A recent study concluded California is in the middle of the worst mega-drought in 1200 years.

We can adapt to future droughts through reducing our water use and switching to more sustainable water uses. We can expand our existing usage of recycled water, replenish our groundwater aquifers and increase our flexibility in crop and municipal uses. - California’s small, rural communities of color are most vulnerable to drought.

According to the Public Policy Institute of California, at least 2,600 well-dependent households experienced water shortages, and roughly 150 small water systems needed emergency assistance during the 2012‒16 drought. As water levels continue to decline throughout California – thanks to the combination of heat, drought, and over-pumping groundwater aquifers– this remains a significant problem for at-risk communities. For more resources on clean drinking water, drought, and community impacts check out the Community Water Center and CleanWaterActions.org.

While addressing the immediate and dire needs for clean water delivery to these households and communities, we can address some of the longer-term needs by funding linkages between small rural communities and nearby larger water municipal supplies; and we can increase our groundwater storage by allowing high flows to spread and recharge local groundwater. - Droughts harm wildlife that live in California’s rivers, streams, and wetlands.

With more than 240 freshwater species in California endangered or vulnerable to extinction, and rivers, wetlands, and forests threatened by the combination of environmental degradation and land development, it is more important than ever that these species have stable environments in which to thrive and reproduce. Decreased flows and rising water temperatures threaten fish and wildlife and have severe implications for regional biodiversity.

We must prevent the near-term collapse of our salmon fisheries by getting the fish to cold water reserves – salmon need cold water streams, where they can successfully reproduce. These cold water streams are endangered by releases from reservoirs that may be too little to sustain salmon, too warm to allow the fish to reproduce or both; and decreases in shaded aquatic habitat that occurs when shade-creating trees are removed from the banks of rivers and streams. We need out-of-the-box strategies to protect cold-water fish species: first, we need a long-term strategy to include environmental water rights in the necessary equation for distributing river water in California. Next, we must collect better information on key flows needed to support fish species[KC9] , and use this information to make our water distribution system fairer and more equitable to the environment and other users. Finally, we must create and restore access to cold-water streams that salmon rely on for key habitat, such as the Feather, Yuba, and Sacramento River tributaries. - California’s intensifying wildfires exacerbate the effects of drought.

We know that drought intensifies wildfires; however, we don’t yet understand how wildfires make droughts worse. We rely on meadows and forests in the Sierra Nevada’s headwaters to provide clean, fresh water downstream. However, when catastrophic wildfire removes the trees and plants and scars the soils, our headwaters are directly exposed to the erosive forces of storms and are unable to absorb rain and snowmelt. As a result, our headwaters experience rapid runoff often carrying tons of sediment into our streams, lakes, and rivers. This means we have more water early in the season and less water during the dry summer months when communities and wildlife need it. Moreover, post-fire runoff often carries pollutants and excessive levels of nutrients causing algae blooms that can be toxic, and accelerating sedimentation – and shortening the lives – of reservoirs and hydroelectric infrastructure. Proper strategic forest management and the use of prescribed fire and cultural burning practices can mitigate these risks and help address poor water quality and sediment loading into streams after wildfires. Studies suggest the costs of prevention are 1/3 the costs of fire recovery.

We must learn to work with fire through ecologically reducing fuel loads. Often, this entails thinning out small trees and brush so that fire is less likely to climb into the high canopy and accelerate its spread across the landscape. Another key strategy is to run low-lying ground fires during the wetter ‘shoulder’ seasons. These prescribed burns stay within carefully guarded boundaries and help to further reduce the fuel load and replenish the soil with nutrients from the ash. Protecting river corridors with smart, locally, and ecologically directed fuel management will keep these areas wetter than the surrounding landscape, and rich in vegetation that can capture sediment from above and provide cover for fish and wildlife.

- Multi-benefit restoration approaches can make a serious impact.

California’s multi-year drought is a problem that necessitates nature-based solutions. Multi-benefit restoration can create a more reliable water storage and cleaner water supply, enhance regional biodiversity, manage flood risk (which is paradoxically also exacerbated by drought), and much more. American Rivers is leading the way on multi-benefit projects such as floodplain reconnection in the Central Valley and meadow restorations in the Sierra Nevada headwaters that have far-reaching benefits for water storage and water quality.

River health is a core facet of California’s drought. Connect with your nearby river and see how you can get involved!

It’s just shy of 9 am on a warm June morning. Cars pull into a dirt pull-off in Yosemite National Park along a large meadow surrounded by granite peaks and the scars of the 2013 Rim Fire. People arrive and hug as they reunite with old friends and colleagues and introduce themselves to new ones. The Sierra Meadows Partnership’s annual meeting is about to begin at Ackerson Meadow.

The Sierra Meadows Partnership (SMP) is a regional collaborative group that works to improve the resources, support, and efficacy around meadow restoration in the Sierra Nevada. This June, the group members met for their first annual meeting in three years at Ackerson Meadow in Yosemite National Park and the Stanislaus National Forest. The plan: to tour Ackerson and learn about one of the largest meadow restoration projects in the Sierra Nevada. Nearly 60 people attended this year’s SMP meeting. Affiliations included the National Park Service, US Forest Service, US Fish and Wildlife Service, nonprofit groups, state agencies, land trusts and conservancies, and more. The purpose of this field tour was not only to learn about the Ackerson Meadow Restoration Project, but also to build connections, network, brainstorm new projects, and strengthen partnerships to enhance meadow restoration across the Sierra.

Ackerson Meadow was this year’s field trip destination because the project is a unique example of how large-scale restoration projects are born from meaningful collaboration. The project is led by American Rivers, Yosemite National Park, and the Stanislaus National Forest, and supported by a diverse team of stakeholders and consultants, most of whom first connected through the SMP. Ackerson has a rich history that stretches back before the arrival of European settlers, to when the Central Sierra Miwok and Tuolumne Band of Me-Wuk Indian tribes would gather and use the abundant resources found in the area. It was homesteaded in the 19th century and a century of livestock grazing, ditch construction, and haying operations contributed to the meadow’s degradation. The meadow is substantial in size at 230 acres, with Yosemite-style granite domes rising from the north. It is home to many rare and endangered plant and wildlife species including the Willow Flycatcher, Great Grey Owl, and slender stem monkeyflower. Unfortunately, the combination of historic land uses at Ackerson resulted in massive ecological and hydrologic degradation, the centerpiece of which is a 3-mile-long gully, 15 feet deep and 100 feet wide, that drains this once vibrant wetland, robbing it of critical functions like groundwater storage, carbon sequestration, clean water supply, and wildlife habitat.

The restoration project at Ackerson is one of the largest meadow restoration projects attempted in the Sierra Nevada. The project includes filling the eroded gully with more than 150,000 cubic yards (15,000 dump trucks!) of soil and wood chips. This will allow the stream to spread across the meadow as it once did, rewatering 190 acres of lost or marginalized wetland habitats, improving water quality to the Tuolumne River system, increasing flood protections, and improving critical habitats for Ackerson’s diverse species.

The project embodies the goals and vision of the Sierra Meadows Partnership, which aims to restore 30,000 acres of Sierra Nevada meadows by 2030. The tour was alive with conversation and debate, while passionate attendees put their heads together in an idyllic setting. As the project leaders discussed the details of the restoration design, tour participants exchanged ideas about soil carbon, beaver dam analogs, and rare wildlife and vegetation in the area.

The SMP: Building Towards 30,000 Acres Together

In addition to being a resource group for partners interested in meadows across the Sierra Nevada, the SMP also conducts an annual survey of member organizations to track progress towards their overarching goal of restoring and protecting 30,000 acres of meadows by 2030. The surveys collect data on key metrics like total acreage, land ownership, restoration objectives and actions, target wildlife species, and projects completed every year.

In 2022, the SMP found that 89 projects, over 16,000 acres, have been completed or are in progress across the Sierra. Seventy of these projects, totaling 9,000 acres, are restoration projects—nine of which were completed in 2021, restoring nearly 400 acres. The others are part of conservation easement and research projects.

The US Forest Service is the primary landowner for meadow projects in the Sierra, almost half of these projects are happening on National Forest System lands. The National Park Service and private landowners also host a significant portion of meadow projects. Improving habitat for wildlife species is a key goal for most of these efforts and some of the most common target species include the Sierra Nevada yellow-legged frog, willow flycatcher, Greater Sandhill Crane, bald eagle, and various native trout species.

Tracking trends in restoration methods is another key part of the survey, and this year channel fill, infrastructure improvements, revegetation, and beaver dam analogs were some of the most common techniques used to bring meadows back to life. These projects were most often funded by the California’s Wildlife Conservation Board, California Department of Fish and Wildlife, and the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, all of which have grant funding programs focused on these critical habitats.

The SMP’s tracking report and events like the Ackerson field tour inspire members of the SMP to learn from one another and share knowledge and expertise to address the ecological health of the Sierra Nevada. As the practice of meadow restoration continues to grow and change with our climate, the SMP’s members continue to learn, adapting their efforts in a changing world to restore these important ecosystems. Meadows are integral to Sierra Nevada watersheds, wildlife, water quality, and by restoring them we are bettering our environments and communities. After spending a day in a beautiful place like Ackerson meadow, with so many others who are passionate and dedicated to such important work in the Sierras, I felt inspired. Not only did I learn about the project and different meadow restoration practices, but I also felt hope for the great work that is happening and saw the passion, joy, and deep interest in all the efforts being made across the Sierras. After the tour finished and the dust settled, environmental advocates from the across the state hopped back in their cars and returned home with new connections and new ideas. Partnerships are powerful when driven by common purpose, and the Sierra Meadows Partnership exemplifies American Rivers’ collaborative and adaptive approach to restoration, reminding us that we are stronger when we work together.

Jocelyn Gibbon is an attorney, policy consultant, and river guide based in Flagstaff, Arizona. She works on Arizona and Colorado River water and sustainability issues through her business, Freshwater Policy Consulting, and guides part-time in the Grand Canyon for Canyon Explorations. She often collaborates with American Rivers as part of her work with the Water for Arizona Coalition. Views expressed in this blog are the authors.

As a Grand Canyon river guide, I know something about facing sometimes harsh and dangerous conditions and finding beauty and meaning in the world. As a water lawyer, I know how difficult it is to align our legal and social systems with physical reality and human values—and yet that we can choose to do so. Right now, as fires rage and this two-decades-long drought takes its toll on rivers and water supplies across the Colorado River Basin, I’m concerned about the choices we will make for the future of the Colorado River and Grand Canyon.

In May, the Bureau of Reclamation announced emergency “drought response” measures to keep the Colorado River system from collapsing over the next year. For the first time in history, the amount of water to be released from Glen Canyon Dam and Lake Powell, through the Grand Canyon to Lake Mead, was reduced part-way through the water year.

Along with other measures announced by Reclamation, this was necessary to keep Lake Powell from further plummeting to calamitously low levels—to where there is not enough water in storage for the City of Page and Navajo community of Le Chee to access their drinking water supplies; to where Glen Canyon Dam can’t produce power; to where water has to be released through emergency outlet tubes never designed for sustained operation.

I am told that these measures were announced immediately to accomplish the needed reduction in dam releases—and hence river flows—without risking a period of actually drying up stretches of the Colorado River.

The reductions come as a disappointment to me and my river guide friends—and our employers, the owners of whitewater rafting concessions that take people on weeks-long, wilderness-style expeditions through Grand Canyon. Already this spring has been windy, and with the boats heavily laden, it can stretch one’s physical limits to get downstream, navigating shifting currents and powerful whitewater. The lower and slower the water, the more time we spend pushing from point A to point B instead of exploring and enjoying the Canyon. Shallow, exposed, sharp rocks mean more time we may spend repairing boats rather than rowing them, and lower water also means less flexibility for campsites after long days on the water. The lower the water the more tired we all are, and our margins for safety and satisfaction narrow.

We river guides are always thinking about flows before a season and before a trip, and there’s been a lot of consternation lately about low flows—this year but in years to come as well. How sharp will the rapids and drops be? How will the paddleboat do in Horn Creek or Waltenberg? Do we need more days for trips billed as “Hikers Specials” if this continues, and will people sign up for trips that long? Will motorboats be able to keep running the river without smashing their props? This spring some guides have been choosing not to row wooden dories in the low water, because of the time and hassle that could go into repair if a dory cracks on a shallow rock. Friends recently returned from a trip with brutal wind and low water, where on the first day they barely made it six miles, pulling into camp with bloody hands and exhausted bodies. This was prior to the announced reductions.

But while we fret and grumble, guides also take great pride in being able to “take what we’re given,” and make the most of challenging conditions. Our job is to help people safely experience a challenging but wondrous place—so they can feel the magic, the fun, the laughter, and the awe, with everything that two weeks in the Canyon can bring into a life. We take satisfaction in finding and sharing the fun and beauty and joy even when the wind is menacing, the heat unearthly, the flows sluggish, or the whitewater gnarly.

Most of us recognize how privileged we are to spend so much time “below the rim” of the Grand Canyon, one of the great wonders of the world.

While not all managed as a true “wilderness” (to the extent such a thing exists), the thousands of square miles of canyon country through which we travel are among the most remote left in the lower 48. We boat through a ten-million-year-old river channel cut through billion-year-old rock—the history of the earth laid bare. There’s nothing like it to make you feel connected to it all; small, yet still significant.

Though dammed at both ends of the 278-mile-long canyon, the river still roils in the beautiful way of free-flowing water, its inhuman and unstopping dynamics speaking directly and musically to the human heart.

While the river channel is no longer subject to a muddy spring flood, summertime trickles, or the full force of upstream monsoon torrents, the Colorado River still supports a remarkable universe of interconnected life and ecosystems—riparian, aquatic, terrestrial, life forms from three of the continent’s four great deserts… full of intricate stories of ecological niches and interconnections that have evolved over eons.

We are privileged—to an extent unjustly—to spend so much time in a place revered by at least eleven tribes and indigenous nations for whom it has been home for centuries, and from whom European settlers took it by force.

Given that sense of supreme privilege, most of my guide friends have accepted the news of Lake Powell’s plummeting—and consequently uncertain flows in the Canyon—with a good deal of stoicism.

The feeling is that we have been lucky—and if there’s no longer enough water for things to continue as they’ve been, we will adapt.

With the drinking water of 40 million people on the line, who are we to be phased by the loss of river flows or our life-altering expeditions through the heart of the Earth? I would more easily feel this way too, if the declining flows had been unavoidable—or were just for this year—or were part of a larger plan to make our use and treatment of the Colorado River or the Grand Canyon more sustainable, caring, or just.

But that is not the case. This year’s reductions from Glen Canyon are in response to an “emergency”—but an emergency that we have seen—or at least could have seen—coming for decades. It didn’t have to be. What’s more, these reductions reflect only a small, temporary stopgap. They don’t fix the massive problem we now face on the Colorado River.

Since 1922, the law governing the Colorado River was set up to apportion and use more water than the river actually provides. The Colorado River Compact allocated at least 15 million acre-feet of water, then a 1944 treaty allotted an additional 1.5 million acre-feet to Mexico. That’s at least 16.5 million acre-feet of water that various states, nations, and water users can legally take out of the river. This doesn’t even include the more than a million acre-feet that evaporate from desert reservoirs and canals or are otherwise lost from the system. To add insult to injury, the Compact doesn’t address the needs of all of the Basin’s tribal nations and flat-out ignores the needs of river ecosystems and wildlife.

Even when the Compact was being ratified there were indications that the river’s flows were less than what was being divided up. In reality, the average flow in recent years has been more like 12 or 13 million acre-feet. Climate scientists and hydrologists tell us that soon we may have to live with as few as 11, or even 9, million acre-feet of water in the system.

In the early years of the big dams, the Upper Basin (Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, and New Mexico) used far less water than allocated and a period of wet years filled up the reservoirs, providing a savings account.

Those days are gone. For about the last 20 years, actual usage throughout the Colorado River Basin has far exceeded the amount of water supplied by the river, and now with the rapid decline of Lakes Powell and Mead, we are seeing the inevitable impacts of this overuse.

What’s more, we have known this is happening, we just didn’t know it would happen so fast. The Basin states and Reclamation have taken steps in recent years to begin to address it, but these steps are proving insufficient, and reservoir levels are plummeting further and faster than imagined. Hence this spring’s emergency measures—measures known to be short-term and inadequate to fix the problem.

Let me be clear, I am very much in support of these measures and recognize their necessity. If flows through the Canyon were not reduced this summer, the situation going forward would be even worse.

But I’m angry that it has come to this, and I’m scared and sad about what may happen next. We are in need of a reckoning: we need to stop using more water than the river provides and blowing through our stored supplies at a terrifying rate. We have needed to do so for years now.

So can our reckoning, when done in a crisis, be done in a way that actually improves the integrity, sustainability, and justice of the system? I am nervous about the potential manifestation of the “Shock Doctrine”—where massive crises are used as an excuse to change systems in ways that otherwise never would have been socially, culturally, or even legally acceptable.

Last fall, an anticipated high-flow through the Canyon was not implemented. These flows are called for as part of the adaptive management practices developed to redistribute diminishing sand and sediment in the post-dam river channel—in turn protecting cultural sites, habitat, and recreational access. The fall flow was decided against, not because there wasn’t the water to do it— it wouldn’t have changed the total amount of water released over the course of the year—but because of costs and concern about reservoir levels dropping to lower levels even temporarily. Here already, we allowed a deviation from what would ordinarily have been undertaken to support Canyon resources and values because of the water supply “crisis”—though doing so did not (contrary to what many assume) help address the Basin’s overall water supply deficit.

I believe that what’s needed to protect our water supplies going forward is fundamentally consistent with what we need to protect the Canyon and the extraordinary ecosystem the Colorado River creates. We must stop using more water than actually flows down the river.

We must all use less water throughout the Basin. This means massive change—but it’s doable, and what’s more, we really have no other choice. It’s long past time.

This reckoning may also mean more years of low annual flows through the Canyon, as we seek to stabilize the system and stop the plummet. Sadly, we may not be able to solve our problems while continuing to release the same amount of water from the Upper Basin to the Lower, through the Canyon.

But if we want to continue to have water to support the millions who rely on it, if we hope to take care of the Grand Canyon and its river, if we want to even have a choice about what flows look like in the future, we need to stabilize this system.

We can’t continue to deny the reality of simple numbers, and we can’t rely on year after year of hurried emergency measures to get us by. That’s not planning, that’s triage.

Crises are opportunities. In the coming months and years, we can fix a mess of our own making and bring increased rationality, stability, perhaps even justice and accountability toward our planet and our people, to our water use in the Southwest.

Let’s take this opportunity, and not use our “crisis” as an excuse to ignore what matters or degrade the health of the Grand Canyon—one of the most beautiful, humbling, and awe-inspiring places on our planet—a place that gives us inspiration to be better people, with broader vision and grander dreams.

If there is one takeaway from the 2021 National River Cleanup photo contest winners, it’s that you have to see it to believe it!

Winner of Most Interesting Cleanup Find

Kevin Tossie snapped a photo of volunteer Alyssa Thomas holding a unique piece of litter, dentures. In celebration of Missouri River Relief’s 20th anniversary, eager volunteers set out on the Big Muddy Sweep. This multi-day camping trip immersed participants in river conservation, cleaning areas of the Missouri River camouflaged to the public eye. Their finds were anything but normal; refrigerators became a common sighting, and one bend was said to have hundreds of straws.

Although these are fascinating discoveries, Tossie states the most meaningful part for him was the change in people’s realizations and attitudes towards water pollution. “They know litter is a problem, but it is not until they’re out there physically removing the trash that their attitudes begin to change.”

Winner of Favorite Cleanup Photo

Adventuring out to create change is something Boardman River Clean Sweep’s Norman Fred is also familiar with. Fred’s winning image pays tribute to their slogan, “Paddling with a Purpose,” by capturing volunteer Harold Lasser paddling a kayak with an old street sign. Setting out to organize effective cleanups, Fred and his paddling club established Boardman River Clean Sweep as a way for the community to help the environment in a safe and fun way.

“There’s so much satisfaction in getting so much joy seeing people do what they love to do and do something that they would most likely not be doing if it weren’t for me.” He notes that the “instant gratification after a cleanup,” wouldn’t be possible without the dedicated volunteers that help make Boardman River Clean Sweep, what it is today.

Winner of Favorite Post Cleanup Photo

Uniquely, Newtown Creek Alliance takes a much more educational approach to attract volunteers. Lor Malotra-Gaudet states that the Newton Creek Alliance is set out on a mission to restore, reveal, and revitalize, and cleanups help fulfill this. Restoring by removing and planting, revealing local creeks to communities, and revitalizing sites by transforming them into public green spaces. The cleanups are led by Brenda, a horticulturalist passionate about teaching others the importance plants play in the water cycle. This newfound understanding creates excitement amongst volunteers such as those depicted in the Dutch Kills Cleanup photo.

“I have noticed that I see hope in people’s faces when they see that they can make a difference; that their actions can translate into larger systems change.” Malotra-Gaudet states when speaking to American Rivers on the impact Newton Creek Alliance has had on her. “There is no typical cleanup, each site has its own specific charms.” If you would like to register or volunteer for an event, please visit American Rivers website under National River Cleanup.

“Ahhh!” That crisp refreshing feeling of immersing yourself in the cool river after a long hot hike, the thrill of the whitewater hitting your face as you hit the rapids, making your way down another gorgeous river – there are truly few things that compare to rivers in the summer.

If you’re looking for a way to make the most of these hot months ahead, check out our summer river bucket list that we have put together to help you get outside and make the most of your summer!

1. Take a nice, relaxing float down the river

You’d be amazed at all the new things you will see from the middle of a river as you get a different point of view. Discover the amazing wildlife that calls the river home. Just make sure you always go with a group, wear a personal floatation device (PFD/life vest), and research before you go to identify any dams or hazards that you need to portage.

2. Explore a Wild and Scenic River near you

Contrary to popular belief, Wild and Scenic Rivers are not only in the west, they are all over the country! These rivers truly are a thing of beauty, and seeing one in person is a treat! You can search for a Wild and Scenic River near you HERE.

3. Have a river cleanup

We’ve all been there: enjoying a hike on a beautiful day, then all of a sudden coming across a pile of trash right beside the river. It’s a sad site but you can do something about it! Take a trash bag with you and pick up trash as you go or designate some time to grab a few friends and take a walk by the river and show it some love by cleaning it up!

4. Learn the history of your local river!

Where does the river originate? What are the native species? What Indigenous lands does your river run through? What challenges might your river be facing right now? Are there actions you can take now to advocate for the health of your local river? A river’s health reflects the health of the community, we should all take the time to advocate for its well-being!

5. Take your kiddos out for an eye-spy challenge!

The wildlife and biodiversity of a river is something to behold. Take the time to introduce the amazing sites of your local river to the next generation! See how many different species of birds you see while you’re out, count the number of different trees you encounter along the way. To make it more interactive, create a bingo card of native biodiversity and see how many different kinds of bingo you and the little ones can get!

6. Watch the sunrise or sunset

We mention the beauty of rivers a lot but if you still need to be convinced, go and watch as the sun slowly illuminates the rushing water of your river. The sounds of the river and biodiversity slowly waking up and starting the day is incredible to witness. If you’re not a morning person wait for golden hour later in the day. The colors of a sunset over a river can only be described as magical. As a bonus, any picture you take will look like a professional took it. Talk about impressive!

7. Go whitewater rafting!

The thrill of whitewater is an experience you will never forget. If you enjoy the rush of adrenaline and corny jokes, book a trip through a nearby whitewater rafting company! Perfect for family get-togethers, bachelor/bachelorette parties or an exciting friend reunion; whitewater rafting is guaranteed to bring ample laughs, create lasting memories and provide stories to talk about for weeks to come.

Whether you travel to a river you have always wanted to visit or spend the summer exploring new aspects of your local river, take a moment to close your eyes, take a deep breath, and appreciate the river that is in front of you. Much of the nation’s drinking water comes from rivers. They house the most incredible biodiversity and are depended upon by hundreds of species year-round. Rivers support us every day, it is time for us to go out of our way to support rivers as well.

The Clean Water Act is getting a workout these days protecting water for people and nature. Today, we are happy to share a great victory on the Black Warrior River, which we listed as one of America’s Most Endangered Rivers® of 2011 and 2013! Our annual report highlighted the impacts that coal mining has had on this watershed that is home to 127 freshwater fish species (4 federally endangered), 36 species of mussels (5 federally endangered), 15 turtle species (1 federally threatened), and numerous other aquatic species.

In a major victory for the health of the Black Warrior River, our partners over at Black Warrior Riverkeeper (and its attorneys, the Southern Environmental Law Center and Public Justice), have lodged a proposed Consent Decree in federal court which, if approved by the Court after a 45-day comment period by the U.S. Department of Justice, will force Drummond Company to clean up its abandoned Maxine Mine site. Consent decrees under the Clean Water Act work to hold corporate polluters accountable for violating environmental laws and permit requirements.

The proposed Consent Decree follows more than five years of litigation to force Drummond to stop discharges of acid mine drainage from a massive six-million-cubic-yard coal mine waste pile at the site near Praco, Alabama. Located on the banks of the Locust Fork of the Black Warrior River, the site has continued to discharge polluted water without a permit since mining operations ceased in the 1980s, harming an invaluable natural resource for residents across Alabama.

“This Clean Water Act victory for the Locust Fork is pivotal for everyone who loves to swim, fish, paddle and boat on the river,” said Nelson Brooke, Black Warrior Riverkeeper. “Maxine Mine’s acid mine drainage has polluted the Locust Fork for decades, and it’s time the site is cleaned up to protect the health of the river and the people and wildlife who depend on it.”

Under the terms of the Consent Decree, Drummond must remediate the site to eliminate discharges of acidic drainage, including sediment, metals such as iron, manganese and aluminum, and other pollutants.

The Consent Decree specifies that Drummond must comply with pollution limits by a specified date, and that the new limits apply even if a less stringent permit is issued by the state. If Drummond fails to meet the final compliance deadline, the Decree imposes penalties of $1,750 per day. Drummond will also be required to set aside funds to maintain and operate treatment systems for at least 30 years. Finally, Drummond must pay $2.65 million in litigation costs and $1 million for a Supplemental Environmental Project to mitigate the effects of its past pollution in the Locust Fork watershed.

Background

Once widely inhabited by Native Americans, the Black Warrior River watershed now provides drinking water to many of Alabama’s population centers, including Tuscaloosa (home of the University of Alabama) and Birmingham (Alabama’s largest city, which obtains approximately half its drinking water from the watershed). The river and its tributaries are national destinations for fishing, boating, paddling, swimming and other recreation.

In June 2016, Black Warrior Riverkeeper filed a notice of intent to sue Drummond to stop the continuous and unpermitted polluted discharges of acidic runoff and mine drainage into the Locust Fork and its tributaries from the Maxine Mine site. Besides being a continuous source of acid mine drainage, the coal mine waste has completely filled what was once a tributary of the Locust Fork.

In September 2016, the groups filed a lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Alabama. In order to address the ongoing pollution and storage of coal mine waste on the Locust Fork, the groups were seeking removal of the mining waste, remediation and/or restoration of contaminated streams, and any other necessary measures by Drummond to stop the illegal discharges at the site.

In May 2019, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Alabama ruled that the surface water discharges of acidic water contaminated with metals and other pollutants violated the Clean Water Act.

In January 2022, the Court ruled that contaminated sub-surface discharges from the site into the river constitute illegal discharges of pollutants through groundwater in violation of the Clean Water Act.

These rulings set important precedent for similar sites in Alabama and the Southeast, affirming the jurisdiction of the Clean Water Act for both surface water and groundwater pollution.

For an interactive map showing the Maxine Mine site, click here.

For a copy of the proposed Consent Decree, click here.

Other Related Victories:

Following up on the Shepherd Bend Mine issue highlighted in our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® listings— building on our listings, the pressure from the dedicated work of our partners led Drummond to abandon their permits for the project in 2015.

Then in 2016, we shared a victory where Alabama’s citizens no longer risk the imposition of attorneys’ fees and costs when exercising their rights under the federal Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977.

Also, check out this visual journey along the Black Warrior River from Nelson Brooke at Black Warrior Riverkeeper!

Wait! There’s More Work to Be Done! Alabama has TWO rivers included on the 2022 list of America’s Most Endangered Rivers®— the Mobile and Coosa rivers!! TAKE ACTION TODAY to help us see more successes like on the Black Warrior River!

It has been a busy and productive spring! Big victories for rivers take time, and we celebrate every positive step. With the help of our supporters and partners, we’re building momentum every day.

We’re using our national policy expertise to forge solutions that benefit rivers in your backyard, and nationwide. Here are three promising developments from just the past few weeks:

Action Days

This week, we teamed up with River Network and Waterkeeper Alliance to host River Action Days. Eighty grassroots river leaders from across the country gathered in Washington, DC to deliver a clear call to action to our elected leaders. In 89 meetings with both Democrat and Republican offices river advocates urged members of Congress to 1) strengthen clean water protections, 2) ensure water infrastructure funds are equitably distributed, and 3) improve agriculture conservation programs. These meetings –your voices — make a difference. We will continue to keep the pressure on, and will seize opportunities to work with elected leaders to drive lasting progress for rivers.

Clean Water

The Biden administration recently released its proposed rule to update the regulatory requirements for water quality certification under the Clean Water Act section 401. American Rivers and others pushed hard for this. The proposed rule strengthens the authority of states and Tribal Nations to protect their rivers and water resources. Tom Kiernan, president of American Rivers said, “We applaud the Biden administration for taking this important step to restore clean water safeguards. Ensuring states and Tribal Nations have the ability to advocate for their rights and interests is essential to protecting and restoring rivers nationwide. The way toward just, equitable solutions is for those most impacted by threats to rivers to play a meaningful role in decision-making. States and Tribal Nations have a vital role to play in creating a future of clean water and healthy rivers everywhere, for everyone.” EPA is accepting public comment on the proposed rule, and you can read more in their press release.

Hydropower

In May, Tom Kiernan testified before the Subcommittee on Energy of the House Committee on Energy and Commerce, in a hearing titled “Modernizing Hydropower: Licensing and Reforms for a Clean Energy Future.” The hearing explored a hydropower licensing reform package, negotiated with conservation groups, the hydropower industry and Tribes. Read Tom’s testimony and learn more about how American Rivers is working to strike a balance, ensuring healthy, flowing rivers and a smart path forward for hydropower in our nation’s energy future.

Summer is almost here! Are you as excited as we are? Long river days here we come! One of our favorite things to do on a hot summer’s day is to spend it on the river with our closest friends and favorite dogs. While you may have introduced your dog to water and the river at a young age, we still want to make sure our dogs are geared up for a fun and safe day. Check out these tips on ways to keep your pup safe!

1. Get your dog a properly fitting life vest

Yes, dog life vests are a thing! A properly fitted life vest is essential to help prevent drowning accidents. Life vests come in an array of sizes so there is guaranteed to be one that is the perfect fit for your pup.

2. Take plenty of breaks & have clean drinking water on hand

Even though you are at the river, the water may not be the best to drink (especially a lot of.). In the summer, dogs are more at risk of dehydration, sunburn and heatstroke. Make sure you are taking frequent breaks with your dog in the shade and make sure they have access to clean drinking water.

3. Keep a close eye on your dog at all times

Even if this is the 100th time you have taken your dog to the river, accidents happen. Making sure your dog is always in eye site is important. Something could spook your dog unexpectedly, they could step on something sharp in the river or they could ingest too much river water which could result in getting an upset stomach. Keeping a close watch on your dog is very important for their safety and for others.

4. Watch out for snakes!

While most river snakes are harmless, there are some species that are not friendly to dogs or humans for that matter. Copperheads, for example, love the water and will sunbathe on the banks of rivers all summer long. Keep your eye out for snakes and make sure you and your canine companion can get around them safely. If your dog is known to jump or try and attack wildlife such as snakes, keep them on a safe, tight leash in order to keep them close and under control.

5. Check your dog head to tail for ticks

After a long day on the river, it’s time to go home and rest. Before plopping down on the couch, give your dog a bath and check for ticks! They can be hard to see, especially on darker fur so combing through a few times wouldn’t hurt. Don’t forget to check between the toes!

We hope you and your pup have the best adventure-filled summer! Please tell us your favorite river moments you have shared with your special dog or companion in the comments below!

5/25/23 UPDATE: The Supreme Court released its ruling on Sackett v. EPA on Thursday, May 25th. The decision dramatically narrowed the scope of the Clean Water Act, undoing protections that have safeguarded the nation’s waters for over 50 years. Because it erases critical protections for tens of millions of acres of wetlands, the court’s ruling threatens the clean drinking water sources for millions of Americans.

“The court’s ruling is a serious blow to wetlands, which are essential to clean, affordable drinking water, public health, and flood protection. [This] ruling puts rivers and people at greater risk from pollution and harm. We urge state officials, the Biden Administration, and Congress to act quickly to safeguard rivers, wetlands, and streams that are so vital to our health and safety, environment, and economy. Rivers should unite us, not divide us.” Tom Kiernan, President and CEO of American Rivers.

Read American Rivers’ full statement here.

Original post from October 3, 2022.

Today, the Supreme Court is considering a case that has the potential to remove Clean Water Act protections for over half our wetlands and streams, putting the drinking water for one in three Americans at risk.

The case, Sackett v. EPA, is backed by polluters who want to weaken the Environmental Protection Agency’s ability to safeguard the streams and wetlands that are critical to our drinking water supplies, wildlife habitat and flood protection.

Here’s a quick summary of why this case is so important, and what’s at stake:

What does this Supreme Court case mean for clean water?

For 50 years, the Clean Water Act, enacted with bipartisan support, has served as our most fundamental tool for protecting waters across the country. Before the Clean Water Act, rivers were treated as sewers, with pollution of all kinds being dumped into them – some so polluted they caught fire.

Now, in the case of Sackett v. EPA, big polluters are arguing that the Supreme Court should weaken the scope of the Clean Water Act. This means countless streams and wetlands all over the country would no longer be protected – and polluters could have free rein to use our nation’s waters as sewers once more. Additionally, wetlands serve as carbon sinks, absorbing CO2 and filtering pollution, making them critically important to the ecosystems they are a part of.

Where are clean water and rivers at risk?

The Supreme Court decision in Sackett v. EPA means more than just redefining the Clean Water Act. Siding with polluters would mean denying communities across the country access to clean water – a fundamental human right.

If the Supreme Court rules against the EPA, the drinking water of one in three people in this country will be at risk. Countless wetlands and streams across the country – vital for fish and wildlife habitat and flood protection for communities – are also at risk. For example, the Court could remove protections for 80% of streams in the Southwest alone.

Who does this case impact?

Undermining longstanding critical safeguards for clean water would impact everyone in our country – especially Tribal Nations, Indigenous communities, low-income communities, and communities of color who already suffer most from toxic water pollution. It is crucial that the Supreme Court sides with communities and upholds equal access to clean water.

To the editor:

Humans are equipped with all manner of technology to mitigate issues these days, much of it to the great benefit of society. Medical technology saves and prolongs lives. Meteorological technology allows us to predict hurricanes, earthquakes and other natural disasters and get people out of harm’s way before they strike. And of course there are many more examples, but there are limits to how we can manipulate our natural surroundings to accommodate our existence on this Earth. There are some things mother nature has created that we simply cannot use technology or engineering prowess to work around.

A prime example: the wetlands that protect people and property from flooding after storms and as sea levels rise as a result of climate change, in addition to providing important habitat values and functions. And, based on a report out this week from the International Panel on Climate Change, these types of impacts will only worsen unless and until we can reverse the trend. More local to coastal South Carolina, it has been scientifically shown that these wetland areas can hold flood waters from large rain events that occur as far upstream as from North Carolina watersheds. Such historic storm events – combined with rising sea level and a higher tidal cycle over time – can be potentially detrimental to our flood vulnerable coastal communities. These flood waters need a place to be stored. In the meantime, we’ll have to plan for and adapt to the changes we can no longer avoid.

Wetlands are nature’s “sponge” that help soak up water from rain and storm events. They absorb and retain excess water until levels recede, serving as a natural flood protection buffer that saves lives, saves homes and businesses, and saves transportation infrastructure. When we think we can outsmart mother nature, that’s when we go wrong – that’s when people and property are harmed, and when our state incurs exorbitant recovery and rebuilding costs.

To respect South Carolina’s wetlands and the appropriate buffers around them is to respect our people. Our region is fortunate to have a bounty of recreational areas that attract visitors and new residents to our state in high numbers, but we must be cautious not to let that fortune become a misfortune. If we continue to build and pave over the wetlands that are here to protect us, expecting that engineering technology can replace these natural systems, we will be making a choice to put people in harm’s way. And we will lose to mother nature every time. The water must go somewhere and, if there are no wetlands to absorb it, then we can expect to find it in our living rooms, shopping malls, and churches – a devastating repeat occurrence that many of our low-lying communities have already experienced.

The northeastern South Carolina coast has a front row seat to how rising sea levels and increased and exacerbated storms are already reshaping the landscape and impacting our people. Let’s leverage that visibility of the climate crisis to inform development decisions that will keep those on the frontlines safe and preserve our coastal communities for generations to come. Let’s demand that our elected officials enact ordinances that give a measure of protection to the natural systems that keep us all safe and add to our quality of life.

When you picture water storage, a water tower on slanted stilts imposed upon a blue sky or a concrete reservoir piping water to the city might come to mind. The issue of water storage has become a high priority as regions such as California experience severe multi-year drought and are impacted by overextraction from aquifers. Reducing municipal water use and streamlining stormwater capture are essential practices, but what we can miss in this conversation is how natural solutions can create comprehensive positive impact. The most climate resilient and long-term strategies to address water shortage lie at our feet, in the meadows that anchor our rivers headwaters and floodplains that extend across the broad lower river valleys.

Meadows and floodplains provide natural reservoirs to store our water. And as they deteriorate, our capacity to provide clean fresh water, maintain biodiversity, and enhance the lives of communities does too.

In California, American Rivers is undertaking critical work to restore meadows in the headwaters that tumble down from the Sierra Nevada. The benefits of meadow restoration extend downstream, beyond the species most directly impacted by restoration (over 50% of vertebrate species in the Sierra Nevada rely on meadow habitats), with almost 60% of California’s water stored in these mountains. To use a hydrological cliché, mountain meadows act like sponges. They store groundwater and regulate flows so that streams are active during times of drought and are limited during periods of excess flows. And the impacts of meadows run deep. Restoring one acre of meadow can yield ½ acre-feet of water per year, translating to enough for the average Californian family. In the Sierra Nevada, overgrazing, ditching, and road and railroad construction over the past two centuries have deteriorated the landscape and prevented meadows from serving this crucial function. It is estimated that over 50% of meadows in this region have a lowered water table. Streams that once meandered through the meadows depositing water into the ground, have become narrow gullies that funnel water out of the mountains too quickly to be absorbed and stored. American Rivers’ restorations at sites like Ackerson Meadow continue to generate broad impact by bringing natural solutions to the fore. By establishing meaningful partnerships and building powerful coalitions and communities of practice, we are working to multiply impact at the landscape-scale.

The story doesn’t end in the headwaters. As a river flows down from the mountains and through river valleys, it overruns its banks during periods of heavy flows and its waters seep into the ground to recharge aquifers. In California’s Central Valley, agricultural production has replaced most of the region’s wetlands, leaving just 5% with us today. This has built a local economy, but also compromised the landscape’s natural capacity to support fish – including salmon, another economy – and other wildlife; and to store water. Levee construction over the past century has disconnected rivers from their historical floodplains, threatening aquatic ecosystems and preventing our natural reservoirs from being replenished. At sites such as Great Valley Grasslands State Park in Merced County, American Rivers is reestablishing the connection between rivers and their floodplains, turning back the clock to ensure rivers follow their natural pathways. These pathways recharge aquifers, native fish and wildlife, and they can recharge your spirit when you visit. We are working in partnership with California State Parks to bring this vision of the Central Valley rivers to life: a vision in which we work in partnership with our rivers to replenish our aquifers, biodiversity, and our own human communities. Rivers do not exist in isolation. They are centerpieces of a mosaic that includes meadows, floodplains, and forests, all of which function cooperatively to store our water and maintain its quality. No human invention can substitute for the effectiveness of natural processes, and with the intensification of the climate crisis we need to look to the natural world for solutions to our most pressing problems.