This is a guest blog by Kelly Richardson, Public Relations Specialist, Nite Ize

It was called the “100-year flood.” In September 2013, the Colorado Front Range saw an uncharacteristic downpour that drenched, damaged, and devastated communities across roughly 150 miles – a scene reminiscent to the ones in Texas, Florida, and Puerto Rico this past month. Almost overnight, the rising waters of the St. Vrain Creek – a tributary of the South Platte River that flows through Longmont, Colorado – overflowed, turning asphalt roadways into raging rivers that quickly saturated homes, leveled businesses, totaled vehicles, and claimed victims.

Four years later, the effects are still felt by the Longmont community and surrounding areas. Many employees at Nite Ize, a Boulder-based manufacturer, are among those that call Longmont home and the grim memories of this unprecedented event still linger.

“Because a large percentage of our employee base lives in Longmont, deciding to work with American Rivers on a company cleanup event in our backyard was important,” Nite Ize Director of Marketing Brenda Isaac said. “We believe in the mission of American Rivers and, as an official supporter of the organization, we were excited to celebrate our partnership with an event that really meant something to our employees and their families.”

Last year, Nite Ize launched a new corporate giving initiative called The Brite Side and chose American Rivers as the first official program partner. “The Brite Side is about focusing on what we want to see in the world around us and working together with organizations that support that vision,” Nite Ize Founder and CEO Rick Case says. “It’s about doing good things, with good people, and always looking for The Brite Side.”

Volunteers pulled a horse from a children’s rocking horse toy set out of the river. | Kelly Richardson

With that mission in mind, 55 volunteers collected 1,500 pounds of trash from roughly 1.5 miles along the St. Vrain Creek and Golden Ponds Park area this past August. Some of the more unusual debris found included a horse from a children’s rocking horse toy set, a University of Colorado letterman jacket, couch cushions, and a silver bracelet with a love note.

These items have a story that many will never know – but more than likely they were washed upon the shores of the St. Vrain during the flood and have remained half hidden and forever forgotten. American Rivers works hard to restore damaged rivers like the St. Vrain to conserve clean water for people and nature. Removing trash and debris from waterways and disposing of it properly is an important part of ongoing flood restoration for the City of Longmont and a task that both Nite Ize and American Rivers were not only dedicated to, but enthusiastic about.

Clearly, it takes many years and many hands to help restore and heal a community after a disaster like this. For all those affected by Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria hang in there. There is a long road ahead, but with the help of friends, family, neighbors, and millions of others around the country, you will endure this.

Mining. Outdated water management. New dams and diversions. Water pollution.

We regularly see these and other threats every year as we work on compiling our annual report on America’s Most Endangered Rivers®.

Right now is your opportunity to let us know what rivers you think are threatened. Do you think that your favorite river is facing a critical decision in the coming year? Have you been wondering… “Why isn’t my river on the list when it faces so many threats?” Let us know!

Hopefully, you have seen our blog posts in recent months talking about threats facing the 2017 listed rivers. We are spreading the word about threats to these special places, thanks to you! Since April, our America’s Most Endangered Rivers blog series (scroll to the bottom of each river page for links) has covered the Lower Colorado River, Bear River, Mobile Bay Basin, Green-Toutle Rivers, Neuse and Cape Fear Rivers, Menominee River and currently the Middle Fork Flathead River. Still to come will be Rappahannock River, South Fork Skykomish River and Buffalo National River!

We are excited to announce that we are now accepting nominations for our 2018 report. Nominations are welcomed from any interested groups throughout the United States.

Rivers are selected based upon the following criteria:

- A major decision (that the public can help influence) in the coming year on the proposed action

- The significance of the river to human and natural communities

- The magnitude of the threat to the river and associated communities, especially in light of a changing climate

The report highlights ten rivers whose fate will be decided in the coming year, and encourages decision-makers to do the right thing for the rivers and the communities they support. The report is not a list of the nation’s “worst” or most polluted rivers, but rather it highlights rivers confronted by critical decisions that will determine their future. The report presents alternatives to proposals that would damage rivers, identifies those who make the crucial decisions, and points out opportunities for the public to take action on behalf of each listed river.

Please help us make the most of this great opportunity in 2018 by nominating a river you think deserves to be included on our list. Deadline for nominations is Tuesday, October 31, 2017. Contact Jessie Thomas-Blate for more information.

This guest blog by Hilary Hutcheson is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series on the Middle Fork Flathead River.

When the community and government agencies prepare for the worst, it’s hard to ignore. And when the worst refers to what can happen to your fishery, it’s impossible not to worry.

“In every stage of life, I’ve lived near railroad tracks. The haunting sounds of night trains with their short-blast-long-howl whistles and steady rumble have always been grounding and comforting to me. I used to love watching gritty, graffiti-clad train cars pushing forward to get an important job done somewhere to my east or west. The history of the Great Northern Railway is fascinating, and as a river guide on the Middle Fork of the Flathead River, I’ve chronicled to guests how John F. Stevens found a route for the railway over Marias Pass and along the beautiful river in 1889. But now, with the fracking boom in Eastern Montana and North Dakota, the haunting feeling I get when a train sounds its whistle isn’t comforting at all. It’s a dark, foreboding moan with a connotation that keeps me up at night.”

The passage above is from an article I wrote three and a half years ago for The Fly Fish Journal about the threat of an oil spill on the pristine Middle Fork of the Flathead River. Back then, locals and tourists could see the mile-long chain of jet-black cars snaking through the canyon. But they might not have known that the antiquated DOT-111 cars from the 1960s, deemed “an unacceptable safety risk” by the National Transportation Safety Board, carried unrefined crude — a mixture of oil and natural gas liquids — propane, methane, and butane. Inside the cars, the gases separate from the liquid, causing a blanket of gas sitting on top of the oil. So, if the railcar cracks open, and the outside air comes in contact with the blanket of gas on top of the oil, a mega explosion will ensue. That’s what happened in the fiery oil train disaster in Quebec that vaporized 47 people in 2013, and in at least 11 additional crashes across the country since then.

Three years ago, the sight of the oil cars winding along the endangered Middle Fork of the Flathead jarred me. I wondered why a mile-long string of crude should be allowed to roll along without any buffer cars in between. If one goes, they all go, I thought. As I researched and asked questions, I was told that would change. I was told that buffer cars are indeed required. But from my front-row seat on the river, I never saw the change. Still today, it’s just black tanker after black tanker. Every day.

Something that has changed in the last three years is that the Middle Fork of the Flathead has received international attention, albeit negative. This year, American Rivers listed it as one of America’s Most Endangered Rivers®. The designation backs me up as I tell my fishing clients that the gin-clear, soul-inspiring water on which we drift is at risk.

The multi-agency and community emergency response plans that formed in the last three years are designed to help execute a fast and effective cleanup in the case of an oil spill. These precautions suggest that unless something changes, it’s not whether there will be a derailment at the river on Glacier National Park’s southern boundary, but when. Which tells me, it’s not a whether the lifeblood that pumps millions into the local economy will suddenly be expunged, but when.

Less than one-quarter of one percent of our nation’s rivers are protected as part of the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. The Middle Fork is one of those special few. With its federal designation as a Wild and Scenic River, this delicate home water should not be faced with an elevated risk of ruin.

It’s been three and a half years since my daughter, Ella, now a freshman in high school, earned a blue ribbon at her school’s science fair for her project about oil cleanup methods. She experimented with tactics like containment booms, skimmers and dispersants. Ella was never able to remove all of the motor oil from her water pans. Today, I’m reminded that what we’re faced with on the Middle Fork isn’t child’s play, and no blue ribbons will be handed out for demonstrating the cleanup of a toxic spill. Next summer, Ella is hoping to get a job at the same rafting and fishing company I joined when I was her age. Maybe she’ll end up being a doctor or lawyer or President, but just in case she wants to be a successful fly fishing guide, she’ll need the resource to be there the way it’s been there for me.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/705/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

Author: Hilary Hutcheson

Hilary Hutcheson is from Columbia Falls, Montana. She is a professional fly-fishing guide on the Flathead River and the Middle Fork of the Salmon River in Idaho, and owns a fly shop in Columbia Falls called Lary’s Fly & Supply. In the off-season, Hilary writes for fly fishing publications, works with a number of industry brands on multi-media projects and travels to lobby congressional delegates on behalf of climate action and public lands.

Hilary Hutcheson is from Columbia Falls, Montana. She is a professional fly-fishing guide on the Flathead River and the Middle Fork of the Salmon River in Idaho, and owns a fly shop in Columbia Falls called Lary’s Fly & Supply. In the off-season, Hilary writes for fly fishing publications, works with a number of industry brands on multi-media projects and travels to lobby congressional delegates on behalf of climate action and public lands.

Without notifying the public, the Trump Administration has moved to allow oil exploration in Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge for the first time in 30 years. In a series of memos the Department of the Interior has proposed to permit seismic studies – that were previously deemed unlawful – to assess the available oil within the Refuge, the first step toward full blown drilling that would destroy the ecological integrity of this pristine area.

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is a vast 30,000 square mile patchwork of wild rivers, wilderness, and coastal plains that serve as a sanctuary for polar bears, caribou, and wolves. It contains one of the best collections of Wild and Scenic Rivers in Alaska, and therefore the country.

The Ivishak, upper Sheenjek, and Wind Rivers were designated as Wild and Scenic Rivers in December 1980 when Congress enacted the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act. These rivers play an integral part in supporting the web of life within the Arctic Refuge. The rivers support salmon and arctic char and the grizzly bears that feed on them. The river valleys provide wintering habitat to the famed Porcupine Caribou herd, some 120,000 strong, and support migratory birds from all over the planet.

The refuge is also fed by over 800 miles of eligible Wild and Scenic Rivers, meaning they have been found by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to be free-flowing and have truly outstanding values. The agency completed a robust analysis of the river resources on the refuge and found exceptional remote recreational opportunities and abundant historical, cultural, and archaeological values worth protecting.

These rivers, including the Porcupine, Canning, Kongakut, and the Hulahula, are truly wild, home to all kinds of wildlife – polar bears, caribou, Dall Sheep, wolverine, and raptors. The Gwich’in Athabascan people rely on the caribou, beaver, and salmon as a part of their living cultural traditions. These same rivers also provide unmatched remote and rugged multi-day paddling opportunities. Given their status as eligible Wild and Scenic Rivers they must be managed to protect their free-flowing condition, water quality, wild character, and their outstandingly remarkable values.

The watersheds of these incredible Wild and Scenic rivers are no place for oil drilling. We must defend our public waters and lands from a corporate giveaway by the Trump Administration and anti-environment members of Congress.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/3475/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

Wetlands and small streams are the first line of defense for communities facing hurricanes and severe storms. Coastal wetlands physically slow down storms by impeding their path to land and minimizing their full force, while freshwater wetlands and headwater streams inland act as sponges, absorbing significant amounts of rainwater and runoff before flooding can occur.

A new study published in August by Scientific Reports looks at the value of wetlands in protecting property. According to the study, coastal wetlands thwarted $625 million worth of property damage during Hurricane Sandy in 2012. While the total savings represent just 1 percent of Sandy’s overall cost ($50 billion), wetlands and streams still helped spare hundreds of homes and thousands of miles of roads from more damage.

Over the past month we’ve watched Hurricanes Harvey and Irma devastate Texas and Florida with record flooding. Unfortunately, this is consistent with the impacts expected from climate change and will be the new normal that we must adapt to. But over the past two centuries, the U.S. has lost over half of its wetlands. Texas alone has lost 52 percent, or 8.4 million acres, of its wetlands from 1780 to 1980.

We need to be doing more to safeguard these vital wetlands. Unfortunately, Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Scott Pruitt and the Trump Administration are pushing a roll back of the Clean Water Rule. The streams and wetlands that this rule protects are the same streams and wetlands that protect lives and property during flooding events. Wetlands span some 110 million acres across the U.S., while small streams that dry up from time to time but come back to life and soak up flood waters during rain events make up more than 60% of the stream miles in the U.S.

Losing the protections for these small streams and wetlands is not worth the risk when it comes to not only flood protection, but also drinking water and the economy – especially with the uncertainty we face with a changing climate.

We have until September 27th to tell the Environmental Protection Agency that we cannot throw out protections for streams and wetlands and we must uphold the Clean Water Rule.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/1597/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

When traveling in Europe this summer, I was struck by how European rivers are central to their lives and history – just like on this side of the Atlantic.

Our first stop was in Paris, where the Seine is a central theme. From a historical perspective, the river was named for Sequana, Goddess of the River, and received the ashes of Joan of Arc. From an artistic angle, the river has been the location of Seurat’s “Sunday Afternoon”, Javert’s death in Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables, Jake Barnes’ late night strolls in Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, and more recently, La La Land’s “Fools Who Dream”. And it’s hard to walk near it without being drawn to the artists offering their souvenir paintings for us tourists to take home.

Bernini’s Fountain of the Four Rivers

Our next city was Munich, where in the 12th century Henry the Lion burned a competitor’s bridge as a way to expand both his wealth and the city of Munich. The Old Town sits close to the River Isar, with the prominent Isartor (Gate to the Isar) still looming large. It is along the river in the English Garden and Maximilian Park where the locals enjoy their sunshine and local offerings (such as at the Chinese Tower Beer Garden). And in the English Garden, you can see locals surfing 24×7, on a channel pulled off of the Isar (click here for an amazing video).

In Italy, Florence’s location was decided by the narrow spot in the River Arno, which later became the birth of the Renaissance. And our stop in Rome was perhaps the most impressive. Here, Rome’s location was defined by an important river crossing for trade, and the river became even more important after the Roman aqueducts were destroyed during the Dark Ages, motivating the Roman Catholic Church to move the city’s center closer to the Tiber River as its main water supply. The Roman love of rivers can best be seen in the Piazza Navona where you can see Bernini’s Fountain of the Four Rivers (1651) (see photo).

There’s an old adage: “If you want a new idea, read an old book”, which completely applies to understanding the importance rivers have played in these European cities, and ones like them here and across the globe. We have always needed our flowing water, and still do.

This guest blog by Trout Unlimited is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series on the Middle Fork Flathead River.

On August 13th, thirty cars of a Montana Rail Link train derailed near Noxon, Montana, sending several thousand tons of coal into and near the Clark Fork River. In 2011, it was 19 cars of a Burlington Northern Santa Fe train carrying 200 tons of frozen chickens and turkeys that spilled into the Middle Fork of the Flathead River near Essex, Montana. Derailments are a common problem across Montana, and the steep, unstable terrain and winding tracks of the western part of the state see more than their share.

Deep in the Bob Marshall Wilderness two crystal clear streams, Strawberry Creek and Bowl Creek, come together to form the headwaters of the spectacular Middle Fork of the Flathead River. The river flows northwest toward Glacier National Park, Highway 2 and the Burlington Northern Santa Fe railroad where it forms the southwestern boundary of the park. This 50-mile wilderness section of the river is available only to the most seasoned and adventurous rafters and fishermen. Once the river reaches Highway 2 downstream of Bear Creek, it becomes generally available to recreational rafters, floaters, kayakers, and fishermen providing some of the most breathtaking whitewater rafting in the nation and impressive angling for Montana’s native fish.

Throughout its nearly 100-mile course, the Middle Fork is protected by Wilderness, National Park, National Forest, and undeveloped state and private lands. These protections yield some of the cleanest and clearest waters found anywhere in the West. The clean, clear, cold, and connected waters of the Middle Fork provide home waters, and much of the last remaining habitat for dwindling populations of federally threatened native bull trout and native westslope trout that have managed to hang on in this difficult environment for thousands of years. This resource attracts anglers, floaters, and photographers from around the country as well as many international visitors.

In the 1950s, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers proposed developing a massive dam on the upper stretch of the Middle Fork at Spruce Park. The dam would have drowned much of the river all the way to Schaefer Meadows in the Bob Marshall Wilderness. The proposal was ultimately defeated due to a concerted effort on the part of Montana and National conservation groups as well as two famous Montana grizzly bear biologists, Frank and John Craighead. In response to this and other threats, 16 different bills proposing river protections were introduced in Congress. On October 2, 1968, the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act was finally signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson. The act stated, in part:

“It is hereby declared to be the policy of the United States that certain selected rivers of the Nation which, with their immediate environments, possess outstandingly remarkable scenic, recreational, geologic, fish and wildlife, historic, cultural, or other similar values, shall be preserved in free-flowing condition, and that they and their immediate environments shall be protected for the benefit and enjoyment of present and future generations.”

In 1976, 150 miles of the North, South, and Middle forks of the Flathead River were protected under the act, including all of the Middle Fork to its confluence with the South Fork near Hungry Horse, Montana.

Today, the Middle Fork is again under threat from development of a different sort. Millions of gallons of incendiary crude oil from the Bakken oil fields of North Dakota pass down the Flathead River corridor every day on its way to West Coast ports for export to Asia. The Burlington-Northern-Santa Fe tracks travel through the steep, unstable John Stevens canyon. Most of the oil continues to be transported in aging DOT-211 rail cars that were never intended to haul hazardous, or explosive cargo.

In a 2016 Risk Assessment, the Montana Public Service Commission (PSC) noted, “In 2015, an average of four shipments of Bakken crude oil transited through Montana each day. A new crude oil transfer facility in North Dakota was expected to increase shipments across Montana by five per week, and at full capacity the new facility could increase shipments by up to 40 trains per week.”

Fortunately, due to a recent plunge in oil prices, this prediction has, thus far, failed to be fulfilled, but we are seeing about 18 100-car trains on this corridor weekly. The PSC also reported that a total of 339 train accidents, excluding highway-rail collisions, occurred in Montana from 2006-2015. Further, “From 2006-2015, 2,035 train cars carrying hazmat materials in or across Montana were involved in accidents, of which 241 were damaged or derailed in five accidents.”

The federal government predicts that trains hauling crude oil or ethanol will derail an average of 10 times per year over the next two decades, causing more than $4 billion in damage and possibly killing hundreds of people if an accident happens in a densely populated part of the U.S.

Any derailment and oil spill on the Middle Fork of the Flathead is simply unacceptable. There would really be no effective way to stop a spill into the river once it occurs, especially if it happened during winter or under high flow conditions. Oil spill containment booms would be completely ineffective in the wild whitewater sections or under ice. They might get some of the viscous mess off the water surface, but there is no way to stop the volatile and soluble compounds, like benzene and toluene, from moving into the downstream aquifer where it would take many years to percolate through and would drastically impact the local economy and health. The effect on the aquatic resources of the Flathead River system would be devastating, both to the environment and to the local economy dependent on that resource.

Responders retrieved only about 2 percent of the oil from the 2011 Yellowstone River pipeline spill under much better conditions. These risks mostly ignore the very real hazards of explosion and fire that have occurred recently in Mosier, Oregon, Culbertson, Montana and the derailment in Lac-Megantic, Quebec, which killed 47 people.

For these reasons and many more, Montana Trout Unlimited and the Flathead Valley Chapter are asking that the Federal Railroad Administration, in conjunction with Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railroad develop a scientifically defensible and public derailment and safety plan for the Middle Fork Flathead River corridor. This irreplaceable resource is much too precious to be sacrificed needlessly on the altar of corporate profit.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/705/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

Author: David Brooks and Larry Timchak

David Brooks is the Executive Director of Montana Trout Unlimited and Larry Timchak is the President of Flathead Valley Trout Unlimited. Montana Trout Unlimited is comprised of 13 chapters, including Flathead Valley, representing approximately 3,900 members.

David Brooks is the Executive Director of Montana Trout Unlimited and Larry Timchak is the President of Flathead Valley Trout Unlimited. Montana Trout Unlimited is comprised of 13 chapters, including Flathead Valley, representing approximately 3,900 members.

This is a guest post by David Schmitt.

Mill Creek was crucial to the development of Cincinnati, Ohio. In the city’s earliest days, it drew settlers looking for rich, fertile farmland, and water power. Mill Creek’s clear, clean water and thick riparian forests provided food, water, and timber. Its broad, flat floodplain was a perfect transportation corridor where industry grew and ultimately built Cincinnati into an industrial powerhouse, “The Queen City of the West”. Unfortunately, over time, that industrial development caused tremendous harm from direct disposal of contaminants, combined sewer overflows, and flooding caused by stormwater flowing over impervious surfaces. The Army Corps of Engineers attempted to address the flooding by channelizing large stretches of the Lower Mill Creek. This not only exacerbated some of the problems, but also cut off public access to the river.

In 1996, American Rivers included Mill Creek on its list of America’s Most Endangered Rivers. The 1996 listing detailed the host of perils faced by the stream, including three Superfund sites on its banks, 31 other hazardous waste sites, and 158 Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) and Sanitary Sewer Overflow (SSO) outflows. At that time, 24.7 of the 27 river miles violated primary contact standards for fecal coliform and E. coli. In the lower 17 miles, the standards were violated in every single sampling site and the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency (OEPA) recommended that there be no public contact with Mill Creek waters.

In 1996, American Rivers included Mill Creek on its list of America’s Most Endangered Rivers. The 1996 listing detailed the host of perils faced by the stream, including three Superfund sites on its banks, 31 other hazardous waste sites, and 158 Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) and Sanitary Sewer Overflow (SSO) outflows. At that time, 24.7 of the 27 river miles violated primary contact standards for fecal coliform and E. coli. In the lower 17 miles, the standards were violated in every single sampling site and the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency (OEPA) recommended that there be no public contact with Mill Creek waters.

By 1997, the trend was actually worse. Two new Superfund sites had been identified, the Army Corps of Engineers was conducting a study to justify walking away from the half-finished flood control project, the OEPA proposed weakening the beneficial use designations in some stream segments, and large scale development was being considered in the northern headwater sections of the stream.

This lead American Rivers to name Mill Creek among America’s Most Endangered Rivers of 1997, calling it “one of the most severely polluted and physically degraded urban streams in the United States” and the most endangered urban river in the country.

Two local non-profits, Groundwork Cincinnati-Mill Creek (“Groundwork”) and the Mill Creek Watershed Council of Communities (‘the Watershed Council”) were formed shortly prior to the American Rivers listings and began the decades-long work of restoring the stream. The listings by American Rivers galvanized greater attention from community leaders, the public, and funding sources.

These two groups have worked tirelessly on projects benefitting both the Mill Creek itself and the surrounding communities. One of the most important steps was reminding community leaders and the public that the stream was even there. The channelization of the Mill Creek removed public access in many areas. Thick, often invasive, vegetation along its steep banks effectively screened it from sight in many others. In a long series of “urban stream adventures” state and federal legislators, mayors, county commissioners, agency heads, reporters, university professors, students of all ages, streamside property owners, sewer district directors, public works directors, environmental regulators, stream restoration consultants, fishing enthusiasts, and attorneys were taken along the stream by canoe to view it firsthand.

With the help of many partners and volunteers, the two groups have completed a huge number of stream improvement projects including hike and bike trails, riparian plantings, wetland construction, dump removal, stream daylighting projects, bank reconstruction, instream habitat improvements, low head dam removal, and best management practices to control flood pulse waters. These include nine bankfull wetlands in the upper Mill Creek to hold flood pulse waters and allow sediment reduction. Throughout the watershed, smaller projects such as rain gardens, green infrastructure, and some larger parking lot runoff reduction projects are having a cumulative impact. The groups also have an extensive education program reaching over 1000 school children per year and providing job training and summer work opportunities.

With the help of many partners and volunteers, the two groups have completed a huge number of stream improvement projects including hike and bike trails, riparian plantings, wetland construction, dump removal, stream daylighting projects, bank reconstruction, instream habitat improvements, low head dam removal, and best management practices to control flood pulse waters. These include nine bankfull wetlands in the upper Mill Creek to hold flood pulse waters and allow sediment reduction. Throughout the watershed, smaller projects such as rain gardens, green infrastructure, and some larger parking lot runoff reduction projects are having a cumulative impact. The groups also have an extensive education program reaching over 1000 school children per year and providing job training and summer work opportunities.

In these region-wide efforts, the Watershed Council and Groundwork have received tremendous cooperation and collaboration from the 36 separate municipalities that call the watershed home. Increased enforcement by Ohio EPA, a federal Consent Decree ordering CSO and SSO remediation, leadership by the county-wide Metropolitan Sewer District, and popularization of these initiatives by the Watershed Council and Groundwork have wrought amazing changes throughout the watershed.

Water quality has improved dramatically as CSO and SSO outflows have been eliminated, direct disposal of pollutants have been outlawed, and remediation of stream side hazardous waste sites has been accomplished. Indeed, the most recent comprehensive water quality surveys of the Greater Cincinnati area shows that the Mill Creek’s water quality now rivals that of the Little Miami River, which is a state and national Wild and Scenic River.

Water quality has improved dramatically as CSO and SSO outflows have been eliminated, direct disposal of pollutants have been outlawed, and remediation of stream side hazardous waste sites has been accomplished. Indeed, the most recent comprehensive water quality surveys of the Greater Cincinnati area shows that the Mill Creek’s water quality now rivals that of the Little Miami River, which is a state and national Wild and Scenic River.

With the improvement in water quality and the replacement of 9 low head dams with constructed riffles has come a tremendous rebound in fish, macroinvertebrate, and other species. The diversity of fish and macroinvertebrate species in the stream have more than doubled over the last twenty years and now meet Ohio’s standards for Warm Water Habitat at most sampling points. Herons, ducks, beaver and many other long-missing species of birds and mammals have returned to its shores.

So has another species that has rarely been seen along its banks in recent years – people! Because of the efforts of Groundwork, the Watershed Council, and many partner groups and agencies, it is now possible to hike and bike on the banks of the stream, as well as to canoe and fish in the stream itself.

A large number of new stream and community improvement projects are on the verge of launching and I believe that within the next decade, the Mill Creek will complete its renaissance and become a magnet to local residents as well as tourists.

While the potential is enormous, continued effort and vigilance are required. Challenges remain in the form of stormwater runoff, effluent from Combined Sewer Overflows and Sanitary Sewer overflows, the channelization of large portions of the stream, and the socio-economic struggles of many of the communities in which we work. In an effort to magnify the impact of their work, the Watershed Council and Groundwork are discussing even greater collaboration and the potential for a merger of the two groups.

While the potential is enormous, continued effort and vigilance are required. Challenges remain in the form of stormwater runoff, effluent from Combined Sewer Overflows and Sanitary Sewer overflows, the channelization of large portions of the stream, and the socio-economic struggles of many of the communities in which we work. In an effort to magnify the impact of their work, the Watershed Council and Groundwork are discussing even greater collaboration and the potential for a merger of the two groups.

If the last 20 years are any indication, the future of the Mill Creek looks bright.

Author: David Schmitt

David Schmitt is the Executive Director of Groundwork Cincinnati-Mill Creek and the Mill Creek Watershed Council of Communities, as well as a Board member of American Rivers.

Two weeks ago, Hurricane Harvey devastated Texas with record flooding. Now, storm surge and rains from Hurricane Irma are ravaging communities across the Southeast.

We may not know the full impact for days. But we do know the damage will be severe and lives will be forever changed.

Irma makes 2017 the third year in a row that the lives of people in the Carolinas have been turned upside down by hurricanes. More than 75 dams failed in the Carolinas as a result of the 2015 and 2016 storms, and record flood levels were exceeded at many creeks and rivers.

Unfortunately, this is consistent with the impacts expected from climate change and will be the new normal that we must adapt to. With increasing temperatures we get more evaporation adding more moisture to the atmosphere. Catastrophic weather events result when increases in temperature and moisture seek to reach equilibrium.

After recovery from Irma we need to reassess how we can reduce the threats from flooding to keep people safe from future storms. We need to look for opportunities to give rivers more room to accommodate floodwaters, keeping people out of harm’s way. We’ll need to improve the safety of high-hazard dams, and reform the National Flood Insurance Program to reduce flood risks.

There is a lot of work to do. But right now, American Rivers encourages our supporters to help with the relief and recovery efforts. Our neighbors need help. We are grateful to all of the volunteers and first responders. Learn how you can help the victims of Hurricane Irma here.

Guest post by Nelson Brooke is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Mobile Bay Basin.

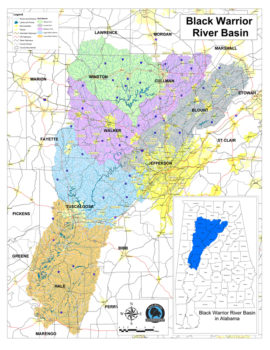

The Black Warrior River watershed looks like a left footprint and drains northcentral Alabama. | Photo by Nelson Brooke

The Black Warrior River gets its name from Chief Tushkalusa, and so does the City of Tuscaloosa, situated on the river’s banks. In Choctaw, tushka means warrior and lusa means black. The Black Warrior watershed is contained entirely within Alabama, drains 6,276 square miles and parts of 17 counties, and measures roughly 300 miles from top to bottom. Black Warrior Riverkeeper has worked tirelessly since 2001 to protect this river from polluters on behalf of all who use it and call it home.

Alabama’s 14 major watersheds, including the Mobile River basin, flow through the perfect blend of geological variation to provide ideal habitats for aquatic critters. Alabama’s 132,000 miles of rivers and streams are home to more aquatic biodiversity than any other state. The Black Warrior River watershed contains over 16,000 miles of streams and is home to 127 fish species, 36 mussel species, 33 crayfish species, 27 snail species, 15 turtle species and over one million humans.

The vermilion darter (Etheostoma chermocki), a federally endangered species, lives in Turkey Creek in Jefferson County, Alabama, and nowhere else in the world. | Photo by Nelson Brooke

The watercress darter (Etheostoma nuchale), another federally endangered species, lives in five springs in Jefferson County, Alabama, and nowhere else in the world. | Photo by Nelson Brooke

The Black Warrior waterdog (Necturus alabamensis), a candidate species for listing under the Endangered Species Act, is endemic to the Black Warrior basin above the Fall Line. | Photo by Mark Bailey, Conservation Southeast

The Flattened Musk Turtle (Sternotherus depressus), a federally threatened species, is endemic to the Black Warrior basin above the Fall Line. | Photo by Mark Bailey, Conservation Southeast

The river’s headwater tributaries – Sipsey Fork, Mulberry Fork, and Locust Fork – begin within the rocky Cumberland Plateau. These rivers are popular recreation destinations for swimming, fishing, canoeing and kayaking.

The Sipsey Fork flowing through the Sipsey Wilderness is Alabama’s only federally designated Wild and Scenic River. | Photo by Nelson Brooke

The Mulberry Fork is a popular whitewater kayaking destination in Cullman County, Alabama. | Photo by Nelson Brooke

Cornelius Falls is one of several waterfalls along the upper Locust Fork in Blount County, Alabama. | Photo by Nelson Brooke

The Locust Fork is home of the annual Locust Fork Whitewater Classic in Blount County, Alabama. | Photo by Nelson Brooke

The Mulberry Fork and the Locust Fork merge west of Birmingham to form the Black Warrior River, which flows southwest through the tail end of the Appalachian Mountains.

The confluence of the Mulberry Fork (L) and the Locust Fork (R) forms the Black Warrior River at Howton’s Camp. Flight provided by SouthWings.org | Photo by Nelson Brooke

The upper Black Warrior River is regularly used for swimming, boating and recreation, and is home to the 33,280 acre Mulberry Fork Tract, part of Alabama’s public lands program called Forever Wild. | Photo by Nelson Brooke

Near Tuscaloosa, the river starts flowing through the sandy East Gulf Coastal Plain. Here, the river’s vibrant floodplain, which floods thousands of acres of bald cypress and water tupelo wetlands, begins flowing through the Alluvial-Deltaic Plain within the Fall Line Hills and Alabama’s Black Prairie.

The river’s sandy banks downstream of Tuscaloosa give way to large sand bars commonly used for swimming, camping and recreation. | Photo by Nelson Brooke

The bald cypress (Taxodium distichum), known for its iconic buttresses and knees, inhabits thousands of acres of wetlands, swamps and oxbows throughout the lower Black Warrior floodplain. | Photo by Nelson Brooke

The water tupelo (Nyssa aquatica) often inhabits the same floodplain swamps as the bald cypress. | Photo by Nelson Brooke

The river’s lower reaches cut through late Cretaceous Period deposits from 66 to 85 million years ago, exposing white chalk bluffs that are filled with interesting fossils of open-marine animals from the time when dinosaurs still roamed and roughly half of Alabama was covered with sea water.

At Demopolis, Alabama, the Black Warrior River flows into the Tombigbee River, which joins with the Alabama River to form the Mobile River, just North of Mobile Bay.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/712/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

Author: Nelson Brooke

Nelson Brooke is the staff Riverkeeper at Black Warrior Riverkeeper, a citizen-based nonprofit clean water advocacy organization dedicated to protecting the Black Warrior River and its tributaries by holding polluters accountable.

Nelson Brooke is the staff Riverkeeper at Black Warrior Riverkeeper, a citizen-based nonprofit clean water advocacy organization dedicated to protecting the Black Warrior River and its tributaries by holding polluters accountable.

Guest post by Steve Jones is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Green-Toutle River.

Rivers are the arteries that deliver life to an ecosystem. They transport the fresh water of the highlands to the plains and oceans. They provide rich stream banks that harbor plants and insects that sustain flocks of ducks and geese and even larger populations of fish. And they provide the clean water for healthy and prosperous cities.

All those things are at stake on Washington’s Green River in Skamania and Cowlitz counties that is threatened by exploratory drilling for copper and gold.

Some people ask what harm could come from just finding out what minerals are there. The answer is plenty of harm, especially to endangered steelhead and salmon that spawn in the Green and downstream in the Toutle and Cowlitz rivers that are part of the ecosystem.

The mountainside where the proposed drilling would occur drains steeply down to the Green and could quickly carry effluent from bore holes into the river. Drilling may also fracture the mountainside and allow increased copper and other metals to leach into the groundwater that would eventually flow to the Green as well. Copper is the metal miners seek most and copper also is a particular threat to steelhead and salmon. Even brief spikes in the copper content of surface water interferes with the ability of steelhead and salmon to find habitat and spawn successfully.

The project is an even bigger threat on the Green, which has been designated a “Wild Stock Gene Bank” for winter and summer steelhead. The habitat needs to be functioning properly for a successful gene bank, and test drilling alone is likely to increase concentrations of dissolved copper entering the Green, let alone the impact of an open pit mine.

To protect the water as well as the plants, insects, fish, wildlife and communities downstream, we must stop this drilling.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/711/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

Author: Steve Jones

Author: Steve Jones

Steve Jones is a member of Clark-Skamania Flyfishers. This group is dedicated to the preservation of wild fish stocks and the natural resources that sustain them. They are further committed to the promotion of flyfishing as a method of angling and, through it, an understanding of and appreciation for the diversity of nature.

My first experience with the Grand Canyon wasn’t in the arid west, standing almost a mile above the Colorado River staring into the enormous abyss; instead it was in an elementary school classroom in Chicago, Illinois. I gawked; eyes wide open at photos of this magical place, perplexed about how something so large and vast could exist. Like many Americans and people around the globe, even without standing at the rims edge, the grandeur of this important place is transmitted through photos, stories, and short films, inspiring us to protect and preserve one of America’s most important and iconic landscapes.

Almost two decades after seeing those photos I made it to the Grand Canyon for the first time. Instead of looking in from above, I gazed up from below, traveling through geologic time as we pushed off from Lee’s Ferry on my first river trip through the Canyon. After that adventure, I traveled back to the South Rim and observed the depth of the Canyon from above. The same feelings of majesty and awe I had as a small child washed over me, solidifying my determination to protect this place.

The Grand Canyon is one of our greatest symbols of the values of wild nature. The canyon represents more than 1.7 billion years of geologic time and is home to wildlife from the bighorn sheep to the endangered humpback chub. Dozens of creeks, springs, and tributaries connect with the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon, including the Little Colorado, Kanab Creek, Havasu Creek, and Bright Angel Creek.

However, the Grand Canyon is under threat. The opportunity to make whopping piles of money has attracted developers who wish to profit from the canyon’s grandeur, rather than admire it as the icon that it is. Threats to the canyon’s seeps, springs, and wildlife include legacy uranium mining claims, the substantial expansion of Tusayan a high desert village, increased air traffic at the lower end of the canyon, and the potential for a gondola shuttling nearly 10,000 people from the rim down to the confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado Rivers. These threats against the canyon are hard to believe – it’s a National Park and a space so surreal that it must be protected. While National Park status does protect it in many ways, substantial risks still exist to the cultural and biological relevance of the confluence, to each of the canyon’s towering rims, to the skies above, and the ancient groundwater below the very surface of the earth.

Listen to Episode 4: Beauty and Risk in the Grand Canyon of We Are Rivers today and take action! Speak up to help protect the Grand Canyon today against these and future threats to one of our most important natural treasures.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/845/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]