Join us this week on our podcast, We Are Rivers as we discuss the issues, opinions, and concerns surrounding Glen Canyon Dam, Lake Powell, and the concept of Fill Mead First in Episode 5: Glen Canyon – Tough Decisions surround a Colorado River Flashpoint.

Fifteen miles upstream from Lee’s Ferry, Glen Canyon Dam halts the Colorado River. Over 50 years ago, before the last bucket of concrete hardened in the 714-ft tall Glen Canyon Dam, Glen Canyon, whose magnificence was said to rival the Grand Canyon was just upstream. As Lake Powell filled, becoming the second largest reservoir in the United States, Glen Canyon was drowned under hundreds of feet of water. Since its creation, all the way through the present, Glen Canyon Dam has had its supporters and adversaries.

There are a variety of issues, opinions, and concerns surrounding Glen Canyon Dam, and whether this dam that has created many controversies over its 50 years of existence should be removed, or at least bypassed. In Episode Five, we hear from a trio of voices on the issue of Glen Canyon Dam, New York Times Bestselling Author Kevin Fedarko, Glen Canyon Institute President Eric Balken, and American Rivers’ Intermountain West Communication Director Sinjin Eberle.

In this episode, we seek to understand the dam’s purpose, its impact on the Upper and Lower Basin water management, and the concept of restoring a world currently under water.

Water levels in both Lake Powell and Lake Mead are low. Bathtubs rings paint the sandstone of both reservoirs demonstrating just how far the lake levels have dropped in the last 15 years. To reduce the impacts of both Lake Powell and Mead reaching critical levels, a number of proposals have been suggested, including an idea that’s received a fair bit of media attention in the last few years, Fill Mead First.

Fill Mead First suggests that drawing down Lake Powell and sending most of its water downstream to be stored in Lake Mead would conserve more water than if the two reservoirs stand alone, because reduced surface area means less evaporation. Fill Mead First does not advocate removing the dam, but instead restoring a somewhat free flowing river by re-opening the diversion tunnels around the dam, and drawing the reservoir down to a low level, called “dead pool.” The water formerly contained in Lake Powell would make its way through the Grand Canyon, to be stored in Lake Mead, raising the surface elevation of the largest reservoir in the United States.

While there are advocates for the Fill Mead First position, draining Lake Powell would have huge, political ramifications. And some believe, the benefits of such a plan are simply not significant enough, at this time, to merit stern consideration. The Upper and Lower Basins are just beginning to cooperate more effectively to reduce risk to future Colorado River water supplies through drought contingency planning. These relationships and collaborations are critical to the overall health of the river and the seven states, two countries, and 37 million people that depend on water in the Colorado River Basin.

It is critical that we reduce water supply risk in the Upper and Lower Basin systems first before draining Lake Powell. And, much more study is needed to confirm whether such a plan would be viable in the first place. Jack Schmidt, a professor at Utah State University, characterizes the potential water savings like this:

The likely water savings to be gained by shifting most water storage to Lake Mead are relatively small in relation to other anticipated changes in runoff in the watershed, especially those associated with climate change. Not only are the savings relatively small, but the uncertainty in the estimated savings is large. Thus, it is not good public policy to implement the Fill Mead First plan at this time. At some future time, however, the potential savings in shifting the primary location of water storage to Lake Mead may be viewed as large. It is critical that the federal government initiate new studies of evaporation loss and ground-water seepage at Lake Powell to resolve these uncertainties so that future decisions about reservoir management can be made with much less uncertainty.

At this time, Lake Powell serves an important role in the balance of the basin, particularly from the perspective of the Upper Basin. In addition to hydropower generation (which a portion of proceeds fund of a number of conservation programs), the Upper basin depends on Lake Powell for water storage to provide security for mandatory deliveries from the Upper Basin to the Lower, especially in drought years. Additionally, the establishment of a demand management program, a key component to drought contingency planning, which compensates water users to voluntarily reduce water use and store the saved water to reduce risk is dependent on Lake Powell. Without Lake Powell in place, in the event of a prolonged drought or supply imbalance in the Upper Basin, the impacts across the Colorado Basin could be dramatic.

It is critical to focus on ensuring that the water demands across the entire Colorado Basin are systematically balanced. In other words, water authorities and interests (such as farmers, municipalities, and tribes) who use Colorado River water, all must continue to work towards collaborative mechanisms that increase water conservation before the contentious debates on Fill Mead First are initiated.

While the viewpoints surrounding Glen Canyon are vast, and often heated, the most important thing when discussing the dam is to maintain open and respectful dialogue to all viewpoints, even fundamentally different ones. Join us as we dive into the complexities surrounding Glen Canyon Dam in Episode 5 of We Are Rivers.

We Are Rivers is now available on both iTunes and Stitcher. Subscribe to stay up to date with new episodes. And, if you find We Are Rivers educational, interesting, and inspiring, please take a moment to rate and comment. This helps others discover this series too! We appreciate your support!

Thanks to the efforts of tribes, fishermen, farmers, conservation groups, and the dam owner PacifiCorp, four dams on the Klamath River in Oregon and California are slated for removal in 2020.

But we need to clear the next obstacle – please speak up by Nov. 6 to keep this restoration effort on track and ensure success.

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), the federal agency responsible for hydropower projects, must transfer the dam license from PacifiCorp to the entity responsible for decommissioning, the Klamath River Renewal Corporation. FERC has opened a public comment period until November 6, and we need you to weigh in to support the transfer.

The Klamath River was once the third largest producer of salmon on the West Coast. Removing the dams will restore the river, revive ailing salmon and steelhead runs, and revitalize fishing, tribal and farming communities.

The four Klamath dams produce a nominal amount of power, which can be replaced using renewables and efficiency measures and without contributing to climate change. A study by the California Energy Commission and the Department of the Interior found that removing the dams and compensating for the loss of power production with efficiency measures and other sources would save PacifiCorp customers up to $285 million over 30 years.

Learn more about the Klamath River restoration effort.

Thank you for speaking up for the Klamath River!

How to submit your comment to FERC:

1. Go to https://ferconline.ferc.gov/quickcomment.aspx

2. Enter your information including e-mail. Open automatic e-mail from FERC, follow link from there to submit comment.

3. In the docket field, enter # P-2082-062 to specify the project.

4. Fill in comment form using our sample letter below, or your own. If you have a personal story, please include it!

FERC requires comments be submitted by November 6th.

Sample letter:

I am writing to support the transfer of the four aging dams on the Klamath River- JC Boyle, Copco No. 1, Copco No. 2, and Iron Gate- to the Klamath River Renewal Corporation (KRRC), and their ultimate removal.

The four Klamath River dams have blocked access to hundreds of miles of salmon and steelhead productive habitat for 100 years. The dams cause toxic algae blooms, reduce productivity of the river, block spawning grounds, and block off cold source water. Removal of the four Klamath dams represents an excellent opportunity to bolster salmon recovery on the West Coast.

The decommissioning and ultimate removal of the four Klamath dams not only makes economic sense, but would greatly benefit the Klamath salmon fisheries and all other Klamath Basin public resources that have been adversely affected by these four dams over the past century.

I urge FERC to approve this proposed License Amendment and transfer to the KRRC for purposes of removing the four Klamath dams and overseeing the restoration of the Klamath River.

This is a guest post by Eric Straw, who paddled a body of water in all 50 states over the summer of 2017 for his Canoe 50 Campaign.

I already miss the rivers… It’s true, even after just returning from paddling a natural body of water in every state. Fortunately, as I discovered on my Canoe 50 Campaign, I don’t have to venture far to find a river. None of us do. From Delaware to the Dakotas and from Mississippi to Montana, every state in the union has a place to paddle, explore, and discover nature anew.

I have a multitude of stories and takeaways from my half-year excursion. Fresh off the water, here are a few that stick out. First off, I believe, more than ever, that our riparian areas are proper focal points for protection and barometers for overall ecosystem health; they are worth seeing, they are worth protecting and they are — along with our diverse population — what makes our nation exceptional.

Despite being from the suburbs, I grew up with a love for the outdoors. As a kid I collected wildlife sightings like baseball cards. For me, the only thing akin to finding a Ken Griffey Jr. rookie in a pack was seeing a rare animal in the wild. Both occurrences put me in a state of bliss only rivaled by an unguarded bowl of candy. Along this canoe trip, I remained enamored by chance encounters with wild animals; my first bear sighting is a prime example.

Paddling down Pine Creek Canyon, Pennsylvania, I floated under passing white clouds, above the glinting water and between the steep canyon walls cloaked in green. The evening set in with a warmth only a fine summer day can provide. Then I saw it — 200 yards down river — the unmistakable shape of a black bear. Trying to calm my excitement, I put on my zoom lens as the bear began crossing Pine Creek. In silence, I canoed downstream as the bear reached the opposing bank and began walking along the shore, towards me. Soon, I was only 30 feet from 300 pounds of fur, teeth, and claws. At a loss for creativity, I called out “Hey bear!” The lumbering creature stopped, turned and looked right at me before disappearing behind a wall of shaking leaves. I passed over the next riffle, dumb grin plastered upon my face. While the spell of baseball cards wore off long ago, I doubt the spell of wildlife ever will.

I didn’t plan this quest with the goal of reinvesting faith in the American People, but after the 2016 election, it became an enduring part of my canoe trip. In every state, I encountered strangers from all walks of life. After meeting hunters, vacationers, bikers, immigrants, fishermen, kids, and retirees, I came away with one thought — people are complicated, but mostly good.

In six months of driving backcountry roads, leaving my car overnight and camping alone, no one ever stole from me. On the contrary, the people I met offered kindness. Countless individuals provided help, rides, meals, beers, etc. On four occasions, strangers gave me cash out of the blue. One kayaker in the Florida Keys put a hundred-dollar bill in my hand. “Go get yourself a good meal and have a great trip,” were his only conditions. I’ve long touted the kindness of the American People, but even I was overwhelmed with the sheer volume of kind gestures during the course of my long paddle.

Now, like most of us, I have many frustrations with our political climate and the normalization of viewpoints that trend in frightening directions. On the nature side alone, I think it’s a shame that the mere word environment has become so polarized. It’s a shame professing a love of nature might somehow instigate a vicious political argument. It’s a shame people feel they need to be either on the side of the economy or the environment, as if improving either inherently destroys the other.

But, after meeting with a broad swath of America and canoeing with people of all political persuasions, I can say this: we all don’t boil down to a choice between, what many regarded as, two poor options. Red state or blue state, I found that the American People, on a whole, do care about how they’re going to leave this land for their kids and grandkids. Whether it’s a turkey hunter in rural Virginia, an outfitter in Alaska, or a Paiute Tribe member in the high deserts of Nevada — people give a damn about their natural world. That should give us all hope.

Along with all the human interactions, the memories of the waterways I canoed will endure. Setting out, I was almost more excited about visiting the unassuming, low tourism budget states than the postcard destinations. Instead of finding mundane, unattractive water bodies, I was floored by the scenic rivers and unsung wilderness areas in states rarely noted for their natural beauty. In April, I swam in the clear blackwater stream on a Wild and Scenic River in Southern Mississippi. In May, I saw thousands of arctic migratory Red Knots gather by spawning horseshoe crabs at the mouth of the Mispillion in Delaware. In June, I surprised a family of river otters, playing in a shallow riffle, in the hills of Ohio. So on and so forth. My canoe quest was a never-ending showcase of American splendor in places you would and wouldn’t expect.

Classic beauty isn’t the reason our rivers deserve our respect and stewardship. Ecosystem health, human well-being, and an array of non-aesthetic factors are as essential. But, boy does it help to stir hearts and open wallets when you realize how stunning our rivers are to behold. I’ve raised money for American Rivers throughout my journey because I believe our nation needs this kind of organization to raise the profiles of endangered waterways and protect natural places, from the unassuming to the majestic. I believe America’s rivers and wildlands are what make us exceptional and they’re worth protecting — grab a paddle and go see for yourself.

Please help me reach my fundraising goal for American Rivers by donating here.

Read more of my state by state adventures at www.shamelesstraveles.com

Let’s talk trash, or more specifically, litter.

American Rivers has teamed up with dedicated litter picker-upper and blogger, Erin Fitzgerald, on an initiative to, you guessed it, pick up litter. But this is no ordinary litter cleanup; we’re adding a twist. Think scavenger hunt.

Are you having flashbacks to your youth? We hope so, because this is going to be fun! It’s an invitation—an opportunity to clean up your favorite trail, park, riverbank, or neighborhood. If you have kids, we encourage you to invite them along. It’s a great stewardship activity for all ages.

And like any good scavenger hunt, there are prizes.

How it Works

Starting this month and throughout next year, we’ll announce a “Litter of the Season.” Then the hunt is on to find the challenge litter, take a picture of it, and tag it to your personal Twitter or Instagram account with the hashtags #MakeAPactPackItOut and #RiverCleanup.

Rules & Reminders:

- Discard of the litter responsibly (recycle it or put it in the trash).

- Feel free to keep the hunt going – you can pick up and tag as much litter as you find, but you’ll only get one entry per person for each season.

- Your picture(s) will populate American Rivers’ Virtual Landfill and Erin’s online gallery, Make a Pact, Pack It Out.

- Grow the scavenger hunt – share this blog post and your trash photos with your friends, family, and co-workers to encourage them to join you (maybe a little friendly competition to see who finds the most of the challenge litter).

Litter Challenge Find #1

Your challenge is to find a discarded wrapper of any kind (candy, energy bar, chips, fast food, etc.).

Prize: Five winners will receive a LOKSAK® bag. LOKSAK bags are re-sealable element-proof storage containers, a perfect complement for outdoor adventures.

Timing

The first scavenger hunt kicks off on Friday, October 27 and ends on Monday, November 6. Your picture(s) must be uploaded to social media account(s) with the hashtags #MakeAPactPackItOut and #RiverCleanup by 11:59 PM, Pacific Standard Time on November 6 to be eligible to win (see complete rules for more details).

Anticipated Scavenger Hunt Seasons

Don’t miss a season – make sure to check American Rivers’ The Current blog and Adventures in Thumbholes’ blog for information on timing. Scavenger hunts will also be announced on social media, so make sure you’re connected (@AmericanRivers and @Thumbholes on Instagram and Twitter).

- October/November 2017

- March 2018

- July 2018

- October 2018

Prizes

Each Litter Season will have a different treasure (prize) up for grabs. Prizes will be in the spirit of sustainability and stewardship. At the conclusion of each scavenger hunt, a winner will be selected at random from all entries.

As environmental stewards, we know picking up and packing out litter not only keeps our trails looking great, but all of our wild places. When litter is left on our lands, rain and floodwater can carry it into storm drains and then quickly into our creeks, rivers, and even oceans.

We look forward to seeing your submissions, as they represent stories of stewardship and care behind every piece of litter picked up. While traditional scavenger hunts focus on a treasure – here the treasure is knowing you left the environment better than you found it.

Author: Erin Fitzgerald is a trail runner from Portland, Oregon. Her blog, Adventures in Thumbholes, has two initiatives (Small Change and Make a Pact, Pack It Out) that focus on stewardship and giving back to the communities where we race and adventure. Erin’s passion for preserving wildplaces has earned her the reputation of a litter-picker-upper, which she happily embraces.

Saturday morning started a bit chilly on October 21, but with a bright sun that shined down on 26 volunteers who showed up to clean the Waccamaw River. This was a blessing as this was the rescheduled annual South Carolina River Sweep clean-up that was previously moved due to Hurricane Irma. We gathered at Peachtree Landing in Myrtle Beach, one of many access points on the Waccamaw River Blue Trail, to clean the landing and then loaded into kayaks and on to paddle boards to head out to paddle 4 miles to Enterprise Landing.

Led by hosts Gator Bait Adventure tours, a local kayak outfitter owned by Chris and Jane Ochsenbein, we started our trek down river. A rainbow of kayaks spanned the width of the river, combing the black water for trash. Our group included teenage international exchange students, laughing college students, families, local river lovers, and even some visitors from Texas.

It was a pleasant surprise to find very little trash in the water. It became a celebration to find even one can or plastic bag. Luckily, the day was beautiful and the river was as smooth as glass- good news for our first-time kayakers. We found substantially more trash at each landing with a common item being cigarette butts- just because they are small doesn’t mean they aren’t litter. It is worth the extra effort to make sure all trash and recycling ends up where it belongs- travel with a trash bag, walk the extra steps to a trash can, and make sure that you pack out whatever you pack in on a boat day.

Thank you to our 26 volunteers and awesome hosts. American Rivers is thrilled to partner with such great people who always leave our landings and water cleaner than we started. We can’t wait to see you on the river next time!

It all began 13 years ago. Keurig Green Mountain’s (Keurig’s) support of National River Cleanup® started in 2004 with a single cleanup event in Vermont, and, since then, has grown to a multi-month program of cleanup events taking place in Tennessee, Virginia, Washington, Vermont, and Massachusetts. This year in Vermont, more than 155 employees volunteered their time over the course of the week, covering 18 miles of the river and collecting a whopping 9,730lbs. of trash. Over the years, hundreds of our Vermont employees have collectively spent thousands of hours cleaning up the Winooski River, which adds up to quite a bit of trash!

Despite foul weather warnings this summer, the majority of volunteer shifts ended up having the perfect weather to go down the river on a canoe. Volunteers were eager for the “tire challenge”, an informal competition between canoes to see who could collect the most tires from the bottom of the river. Fortunately, the competition wasn’t that strong this year as there was significantly fewer tires in the river this year as in previous years. In total, Keurig’s Vermont volunteers collected only 154 tires this year v. last year’s 345

Despite foul weather warnings this summer, the majority of volunteer shifts ended up having the perfect weather to go down the river on a canoe. Volunteers were eager for the “tire challenge”, an informal competition between canoes to see who could collect the most tires from the bottom of the river. Fortunately, the competition wasn’t that strong this year as there was significantly fewer tires in the river this year as in previous years. In total, Keurig’s Vermont volunteers collected only 154 tires this year v. last year’s 345

In addition to the tire competition, volunteers also worked together to find the most unique trash items along the river. The top finalists included a vintage wagon wheel, an old water canister, and a very wet teddy bear. Though items like the wagon wheel and water canister weren’t easy to remove, teams worked together to uncover the items from the mud and load them onto their boats for removal. In the end, everyone collected their fair share of interesting trash and left with some great stories and shared experiences with their co-workers.

Volunteering opportunities are a great way to connect with your team and meet new people within the company. Whether volunteers came down as individuals or as part of a team, everyone shared the fun going down the river. By the end of the shift, everyone had made a new friend, learned something new, and did their part to make the Winooski River just a little bit cleaner! Until next year…

Author: Sarah Shutt, a Northeastern student majoring in Human Services on a six month Sustainability Co-Op with Keurig.

Author: Sarah Shutt, a Northeastern student majoring in Human Services on a six month Sustainability Co-Op with Keurig.

Time is running out for what were once the largest salmon and steelhead runs on the planet – the magnificent runs of the Columbia River Basin in the Pacific Northwest. And now politicians are attempting to stand in the way of science and salmon recovery.

Historically, over ten million Columbia River Basin salmon and steelhead existed, but the number plummeted to fewer than 1 million in 1995, precipitating into the listing of 13 different species or populations of Columbia and Snake river salmonids as endangered or threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

Salmon and steelhead have a complex and fascinating lifecycle, one that begins in freshwater streams, segues into the ocean for a period of time, and ends in the same stream in which it was born, where the ones who survive their often long and daunting migration return to spawn and die. These salmonids are a remarkable, resilient keystone species but they are vulnerable at every stage of that life cycle.

From the 1930s to the 1970s, a system of dams was constructed by the federal government on the Columbia and Snake rivers transforming the rivers into a series of slow-moving reservoirs. The dams impede salmon and steelhead from reaching prime headwaters habitat and injure or kill the migrating fish as they travel through fish passage facilities. The reservoirs now inundate previous river habitat precious to the survival of these salmonids.

Over the past 25 years, scientific research, tribal treaty rights, and environmental advocates along with over $10 billion in federal investment have helped keep these populations from becoming extinct, but they are hanging on by a thread.

American Rivers along with our partners have been tireless advocates for managing the federal dams in the Columbia Basin in a more fish friendly manner, which includes considering the removal of the four lower Snake River dams – Lower Granite, Little Goose, Lower Monumental, and Ice Harbor dams. Part of this advocacy required employing a legal strategy, which over the past two years successfully resulted in two carefully-considered decisions by the U.S. District Court in Portland, Oregon.

The first of these legal victories occurred in May 2016, when the court found the most recent plan for managing the federal dams on the Columbia and Snake rivers violated the Endangered Species Act and the National Environmental Policy Act and would not protect wild salmon and steelhead from extinction. The court’s decision means that the managing federal agencies need to develop a new plan that carefully considers all reasonable dam management alternatives, including removal of four lower Snake River dams. It also requires the federal agencies to examine the effects of climate change on wild salmonids and the federal hydro-system. As proposed by the federal agencies, the court gave the agencies until 2021 to complete this analysis and plan. This planning process is currently underway.

This past April, a second court decision found that current dam operations based on the illegal 2014 plan – would cause “irreparable harm” to salmon and steelhead already facing extinction. The court required federal, state, and tribal fishery scientists to work together to develop a near-term dam operations plan that would release more water over the dams’ spillways to improve juvenile salmon survival. That work among the fishery experts is underway and the new annual operations are scheduled to begin in spring 2018. These new “spill” operations will comply with all state water quality standards and are widely considered the most effective near-term measure available to bring immediate benefits to salmon.

Despite federal agencies and fishery scientists being underway with these processes, politicians have decided to stand in the way of science and salmon recovery.

In June 2017, Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-WA) and four other members of Congress introduced H.R. 3144 asserting that this legislation would “support the Federal Columbia River Power System and the benefits it brings to our region . . . ” In fact, the bill would do just the opposite: It would thwart efforts to protect endangered wild salmon and steelhead, hinder development of a more efficient and reliable power system, and risk raising power rates.

How? The bill seeks to lock-in status quo hydropower operations on the Columbia and Snake rivers that primarily benefit taxpayer subsidized barge transportation and continued capital investments in four expensive and unnecessary federal dams on the lower Snake River that should be removed to help save wild salmon and steelhead and the public’s money. Five different times over the past 16 years, the federal courts have rejected plans as illegal that would continue these business-as-usual operations.

H.R. 3144 is legislative overreach.

The actual purpose of H.R. 3144 is never stated or acknowledged in the bill: to overturn these two carefully-considered court decisions. Without ever mentioning them, H.R. 3144 would block both judicial decisions by requiring that, until 2022, dam operations must follow the illegal dam management plan rejected by the Court in 2016.

In addition, H.R. 3144 would seek to prevent any study, analysis, or consideration of dam management alternatives, such as additional increases in spill or breaching of the four lower Snake River dams. This legislative effort to circumvent the courts and the requirements of our nation’s environmental laws is contrary to the way the rule of law is intended to work in a democracy. Sadly, it would also protect a failed and costly status quo while blocking the opportunity to create a new plan that both reflects regional stakeholder input and works to achieve salmon and steelhead recovery.

American Rivers and our partners will work hard to prevent H.R. 3144 from becoming law. Please join us by contacting your U.S. Representative and requesting that he or she opposes H.R. 3144.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/5125/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”4″ center=”yes”]Take Action »[/su_button]

Millions of pounds of trash end up in our rivers and streams every year. It’s more than just an eyesore. It can contaminate your drinking water and threaten the life of all who depend on it- human and nature. But in Conway, South Carolina, our volunteers are doing something about it.

American Rivers partnered with Winyah Rivers Foundation and the Waccamaw Riverkeeper to clean up the Waccamaw River Blue Trail. The Waccamaw River is over 140 miles of gorgeous blackwater that is the color of tea on a sunny day or dark coffee when the clouds pass through. With more extreme weather events occurring in the region, the Waccamaw River has experienced some historical flooding in recent years. While flooding is scary in its own right, it also increases the amount of trash in the river as waters flow over typically dry areas picking up all trash and bringing it to the rivers, streams, and swamps.

On September 2, 2017, we held a clean-up event in downtown Conway. 77 people of all ages showed up to scour the land and water to leave out river pristine. With over 300 volunteer hours at this one event, 92 bags were collected and sorted into 57 bags of recycling and 35 bags of trash. Every clean-up always finds some odd items from rocking horses to patio furniture. The most unusual item this time was an above ground pool hauled in by the Burge family. Including the pool, almost 2000 pounds of waste was collected in a half day.

These are astounding numbers and we are so proud of these amazing volunteers. This effort also shines a light on a bigger problem of pollution in our society. You may not think twice about that fast food trash or drink can you toss out your window or flies out of the bed of your truck, but there is a good chance that its journey will end in our waterways. And a good rule of thumb for when you are spending a day on the river is to always pack out what you have packed in – this means take all your trash with you. It takes little effort and benefits our rivers and communities.

[metaslider id=40082]

** Editors note — this post was updated on 10/3/2018 with new information post-Hurricane Florence

Hurricane Florence brought its full force to bear on the Carolinas. Winds of 100+ miles per hour caused wide-ranging damage, but the biggest impacts of this slow-moving storm were from rainfall – up to 3 feet in some areas. Record flooding occurred in southeast North Carolina and northeast South Carolina, flooding which persists in some areas almost 3 weeks after the storm.

The loss of human life, damage to infrastructure and displacement of whole communities are staggering:

- 48 lives lost – 39 in North Carolina and 9 in South Carolina

- 840 road closures including portions of Interstate 40, Interstate 95 and other major highways

- All-time record flooding of the Black, Cape Fear, Lumber, Neuse and Waccamaw rivers

- 61,000 people requesting disaster relief according to the NC Department of Public Safety

- $1.2 billion in federal disaster funds requested by South Carolina’s governor

- Several breaches of Lake Sutton Dam that resulted in coal ash being spilled into the Cape Fear River

- 11 dam failures in South Carolina including 5 significant hazard dams

This makes the fourth year in a row that the region has been walloped by tropical cyclones. Will 2019 be the fifth? Unfortunately, the blog’s message is just as relevant today as it was a year ago or the year before that. Hurricanes are more frequent, getting stronger and lasting longer according data from NOAA’s Earth Systems Research Center and reported by The Guardian. We have endured 15 above normal hurricane seasons during the past 24 years – a record. State elected officials in the Carolinas must take immediate and substantial steps to better prepare for the future hurricanes that climate change will bring.

—Original Blog from 10/6/2017 below —

Harvey. Irma. Jose. Maria. Is there an end to the alphabet soup of 2017 hurricanes affecting the Southeast and our citizens in the Caribbean islands? Most of the focus has been on other states and territories – Texas, Florida, the US Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico – and deservedly so as those areas have suffered devastation of historic proportions. We are somewhat fortunate in the Carolinas to have been spared the worst of the cyclones’ wrath this year and that no “rain bombs” caused dams to fail as with Hurricane Juaquin and Matthew. Yet often overlooked is that five people died in South Carolina due to Hurricane Irma, homes and businesses flooded, and life is not back to normal for many people along the Carolina coast.

This makes the third year in a row that hurricanes have blown past the Carolinas.

Final damage and economic impact estimates from Irma are still not known. We do know that 2015 and 2016 hurricanes and resulting floods combined damaged more than a quarter million homes, caused 93 dams to fail and, most tragically, resulted in the loss of 52 lives. The 2015 floods are South Carolina’s second most costly environmental disaster causing more than $12 billion of damage and economic impacts. Hurricane Matthew and its floods rank among North Carolina’s top environmental disasters with an estimated $2.8 billion dollars of property damage and $2 billion in economic impacts.

For decades scientists have been warning us that a warmer climate will bring more frequent and more violent storms to the Southeast. While the models are complex the concept is simple. Warmer temperatures evaporate more water adding more moisture to the atmosphere. This leads to more precipitation and more large storms.

That is exactly what has impacted the Carolinas for three years in a row. Will 2018 be the fourth?

There is no doubt that flooding is becoming more frequent and more severe.

The impacts of floods out rank all other natural hazards and predictions indicate that the size of nation’s floodplains will grow by 40 to 45% by the end of the century putting even more communities in harm’s way. We must adapt to changing conditions to ensure the safety of our citizens, their homes and our roadways from increasing storms and floods.

The political leaders of the Carolinas have largely ignored decades of warnings from scientists relying instead on a business-as-usual approach to floodplain development, poorly planned growth and dam safety. North Carolina actually outlawed the use of climate science for evaluating future sea level rise.

Will the lives lost, property damaged and dams failed be enough to convince the states’ leaders that we cannot continue business as usual?

Here are commonsense solutions to adapt to increasing floods that both states should put in place to save lives and protect property.

- Protect and restore floodplains: Naturally functioning floodplains store floodwaters and reduce downstream flooding. We need to take advantage of these natural defenses.

- Get people out of harm’s way: Poorly planned growth has allowed development in flood prone areas, putting people in harm’s way. We need to replace developed areas with green spaces that can absorb floodwaters and buffer communities from damages. Charlotte, Milwaukee and Davenport, Iowa have been leaders in taking 21st century approaches for water and flood management.

- Strengthen state dam safety laws and programs: Ninety-three failed dams make it clear that our current standards, especially for earthen dams which are by far the most likely to fail, do not provide safety with the reality of today’s extreme flooding.

- Remove dams that do not meet safety requirements: We cannot wait until dams fail to take action. Poorly maintained and improperly designed dams need to be removed to protect downstream communities and infrastructure before they fail.

The leaders of the Carolinas must learn from the hurricanes and disastrous floods of the past three years, and enact 21st century solutions that protect families from future floods. We must adapt to changing conditions and cannot continue business as usual while lives are lost and our communities are devastated.

This guest blog by Ben Long is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series on the Middle Fork Flathead River.

It says a lot about just how difficult conservation is when you consider that the Middle Fork of the Flathead River in Montana is simultaneously one of the most protected rivers in America, and one of the most threatened.

The Middle Fork is the only place where I’ve ever caught a fish by accident, with my teeth.

I was knee deep in the Middle Fork in Montana’s Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex. My two companions and I hired a local pilot to ferry us and our gear in to a wilderness airstrip in his Cessna. From there, we rafted 30 miles in three days to US Highway 2.

The evening rise of cutthroat trout was popping all around. The forested slopes and peaks were aglow in the sunset. To take my camera out of my pocket, I held my rod sideways in my mouth, like a pirate biting a cutlass.

Suddenly, I felt a jolt through the roots of my teeth. The line with a golden stonefly pattern had been drifting downstream and a trout hit it hard. I jerked my chin to set the hook, spit out the rod, and landed the pan-sized westslope cutthroat trout.

This is truly wild, native fishery. The ancestors of these trout pioneered these waters as the glaciers melted 10,000 years ago. They have been hungry all the while. I caught and released 24 cutties in less than 90 minutes.

The Wild and Scenic Rivers Act was passed in 1968. Today, the law protects more than 12,000 miles of 208 rivers in 40 states. One of the very first rivers recognized under the law was the Middle Fork Flathead.

The Fork is 92 miles long. The uppermost 45 miles or so flows through a formal Wilderness Area, where all commercial and industrial development and even motorized machinery are prohibited by an act of Congress. Wilderness is the gold standard of preservation for our public lands.

The lower 45 miles of the Middle Fork, its northern flank is Glacier National Park – again a landscape with gold-standard habitat protection.

But that same 45 miles – from Bear Creek to Blankenship Bridge, the Middle Fork is also flanked by a railroad track on its south bank. The Great Northern Route is one of the busiest freight routes crossing the West. It crosses treacherous and rugged country, steep forests prone to landslides, avalanches, blizzards, floods, and forest fires.

And there’s the rub.

The Great Northern Route has been subject to dozens of train derailments over the years, some of them overturning dozens of rail cars. It’s just dumb luck that so far those trains have been carrying mostly inert materials. (Most notoriously, the trains spilled tons upon tons of corn, which was buried, fermented, and was feasted upon by bears who got drunk on the sour mash.)

Now, the Great Northern Route is being used to haul crude oil from the Bakken oil patch to coastal ports. The contents of these trains is toxic, explosive, and carcinogenic. Rotten corn is nothing in comparison.

To be fair, the Burlington Northern-Santa Fe Railroad has taken steps to improve safety on the Great Northern Route. Derailments, after all, are costly problems.

At the same time, as someone who loves the Middle Fork dearly and cherishes clean water, the idea of an oil spill seems like playing a forced game of Russian roulette. So far the firing pin has clicked on empty chambers. Next time?

The Middle Fork is one of America’s finest, most pure bodies of water. It is a special place that deserves special attention and a special plan to keep it pristine.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/705/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

Ben Long is a conservationist, father, and outdoorsman in Kalispell, Montana. He is senior program director for Resource Media. You can follow him on Twitter: @BenLong1967.

This guest blog by Jack Stanford is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series on the Middle Fork Flathead River.

When I came to the Flathead in 1971 to begin work at the University of Montana’s Flathead Lake Biological Station, I was stunned by the clarity and purity of Flathead Lake. All these years later, water quality in the lake remains largely pristine; indeed, it is the cleanest large lake in the world with significant human population in the watershed. That is largely because almost all of the inflowing water comes from Glacier National Park and surrounding wilderness, and people have taken care to minimize pollution through adherence to forestry best management guidelines, floodplain protection, and effective treatment of urban sewage.

However, one thing that has stayed the same for years is the presence of the railroad and highway corridor along the Middle Fork Flathead River and on past Whitefish Lake. In the early years, most of the commercial hauling involved materials that were fairly innocuous if spilled into the rivers. Wrecks inevitably occurred. I’ve seen several over the years: lumber, grain, TV,s and other goods floating down the river from train derailments and a couple of small petroleum spills from truck wrecks.

Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) says the rail line is as modern and safe as it can be given the terrain it follows through this mountainous river corridor. However, a good share of the rail traffic these days involves long trains composed of 80 to 100 or more tank cars full of petroleum products, including crude oil. Actually, BNSF does not say exactly what’s in the tankers because they are not required to do so. Nor do they have a publicized, robust plan for prevention, much less, what to do if a huge spill does occur.

Let’s say a derailment happens in Nyack, Montana — several huge tankers brake open and thousands of gallons of crude oil spill into the river. It would be a toxic mess beyond comprehension, going rapidly downstream and penetrating into the alluvial aquifers killing everything in its path that cannot somehow get out of the way.

Oil would be in Flathead Lake within hours.

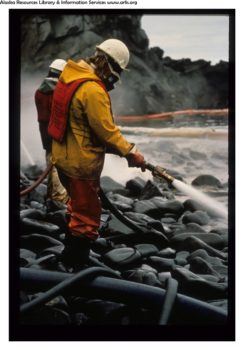

A worker assists in the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill cleanup in the Prince William Sound September 11, 1989. | Photo: ARLIS Reference

Even if soaker booms were deployed in time to be ahead of the plume, they would only capture some of the heavy stuff, while the volatile and soluble pollution would escape into our environment where it will persist for decades (think Prince William Sound – the Exxon Valdez spill impacts remain prevalent in that ecosystem 28 years later).

Crude oil and processed fuels contain a wide variety of pollutants including, for example, benzene and PCBs that are extremely toxic in high doses and cause cancer and other health issues, even in extremely low doses. Scientists at the Biological Station have monitored small truck spills around the lake in the past, and the pollution was measurable for years even though enormously expensive restoration was implemented. Suffice to say that our lives in the Flathead will never be the same if a major railroad oil spill occurs in our ecosystem.

What can be done to prevent a disaster?

Well, it has to start with BNSF recognizing that a major spill simply cannot happen. Our water, our national park, our rivers, and our lake are priceless.

No amount of post-spill payoffs or restorations will repair the damage. I and others have repeatedly called for serious, comprehensive consultations with BNSF, civil authorities, land and water management agencies, and the public on preventive measures. It starts with complete transparency on track and train monitoring, along with complete clarity on what is in the tankers for every train that passes through our watershed (the same should apply to tank trucks on the highways).

Next, stringent safety measures must be developed and implemented, such as speed limits and additional snow sheds to protect the track from avalanches. Of course, planned and practiced actions for response if a derailment does occur are also important, but effective safety measures to make a worst case scenario derailment, spill, explosion, and fire as unlikely as possible are absolutely essential. Response actions have to take into account the wide array of chemicals involved and detailed knowledge on how those chemicals mobilize in the environment. Consultation will raise other issues.

The bottom line is to think the unthinkable. It could happen. We need to minimize the chance and be ready if and when it does occur so that the impact is minimized. Thousands of people just found out what “worst case scenario” means in Houston. Let’s not let a worst case scenario happen here.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/705/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

Jack Stanford is Director Emeritus of the University of Montana’s Flathead Lake Biological Station.

This is a guest blog by Kelly Richardson, Public Relations Specialist, Nite Ize

It was called the “100-year flood.” In September 2013, the Colorado Front Range saw an uncharacteristic downpour that drenched, damaged, and devastated communities across roughly 150 miles – a scene reminiscent to the ones in Texas, Florida, and Puerto Rico this past month. Almost overnight, the rising waters of the St. Vrain Creek – a tributary of the South Platte River that flows through Longmont, Colorado – overflowed, turning asphalt roadways into raging rivers that quickly saturated homes, leveled businesses, totaled vehicles, and claimed victims.

Four years later, the effects are still felt by the Longmont community and surrounding areas. Many employees at Nite Ize, a Boulder-based manufacturer, are among those that call Longmont home and the grim memories of this unprecedented event still linger.

“Because a large percentage of our employee base lives in Longmont, deciding to work with American Rivers on a company cleanup event in our backyard was important,” Nite Ize Director of Marketing Brenda Isaac said. “We believe in the mission of American Rivers and, as an official supporter of the organization, we were excited to celebrate our partnership with an event that really meant something to our employees and their families.”

Last year, Nite Ize launched a new corporate giving initiative called The Brite Side and chose American Rivers as the first official program partner. “The Brite Side is about focusing on what we want to see in the world around us and working together with organizations that support that vision,” Nite Ize Founder and CEO Rick Case says. “It’s about doing good things, with good people, and always looking for The Brite Side.”

Volunteers pulled a horse from a children’s rocking horse toy set out of the river. | Kelly Richardson

With that mission in mind, 55 volunteers collected 1,500 pounds of trash from roughly 1.5 miles along the St. Vrain Creek and Golden Ponds Park area this past August. Some of the more unusual debris found included a horse from a children’s rocking horse toy set, a University of Colorado letterman jacket, couch cushions, and a silver bracelet with a love note.

These items have a story that many will never know – but more than likely they were washed upon the shores of the St. Vrain during the flood and have remained half hidden and forever forgotten. American Rivers works hard to restore damaged rivers like the St. Vrain to conserve clean water for people and nature. Removing trash and debris from waterways and disposing of it properly is an important part of ongoing flood restoration for the City of Longmont and a task that both Nite Ize and American Rivers were not only dedicated to, but enthusiastic about.

Clearly, it takes many years and many hands to help restore and heal a community after a disaster like this. For all those affected by Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria hang in there. There is a long road ahead, but with the help of friends, family, neighbors, and millions of others around the country, you will endure this.