Montana’s beloved Gallatin River got some good news just before Thanksgiving. Following a year and a half of monthly meetings, a collaborative stakeholder group released its final recommendations for how the booming resort community of Big Sky should best manage its water supply and wastewater disposal. Notably missing from the recommendations was direct discharge of treated wastewater into the river, which American Rivers has long opposed. Instead, the group recommended that Big Sky seek to become a model community by pursuing innovative solutions such as using highly treated wastewater to irrigate local golf courses and make snow on low-gradient ski slopes in early winter. For more information on the Big Sky Sustainable Water Solutions Forum’s final recommendations, check out this article from Explore Big Sky in which American Rivers is quoted.

The period to submit scoping comments regarding the proposed Black Butte copper mine in the headwaters of the Smith River in central Montana closed on November 16, 2017. According to the Montana Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), the agency received about 10,000 comments during the scoping period. Of those, 8,030 people, or just over 80 percent, commented through American Rivers’ action alert.

The fight is far from over, though. Montana DEQ will use these scoping comments to frame their environmental assessment process throughout 2018. Included in this process will be more opportunities for the public to comment, and we will need your help again.

The Smith River is one of Montana’s most cherished floats. Every year thousands of people apply for a multi-day permit to boat its limestone canyons, sample its world-class fishery, and camp underneath its starry skies with family and friends. Because of the proposed Black Butte mine in its headwaters, the Smith River was named one of America’s Most Endangered Rivers® in 2015 and 2016.

Thank you for helping us keep wild rivers like the Smith free of acid mine drainage and other pollutants. We couldn’t do it without you! For more information on the proposed copper mine in the headwaters of the Smith River, and to stay informed, please visit: https://www.americanrivers.org/river/smith-river/

This guest blog by Lin Wellford is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series on the Buffalo National River.

Corporate agricultural interests have worked hard to make the environment a wedge issue. They would have you believe that ‘environmental extremists’ (their term for anyone who is actively involved in protecting our shared resources) are anti-farmer and anti-progress. However, I recently came across an article by a third generation farmer and rancher who has seen first-hand how raising large numbers of animals in metal buildings and disposing of tons of concentrated waste on limited acreage has damaged his neighboring land and water.

Thomas L (Tom) Warner of Decater, Indiana, wrote an article that appeared in the Greensburg Daily News. In it, he details problems caused by an industrial livestock operation that polluted the private lake on his property. As he put it, “I am an aggrieved Indiana resident, voter, and taxpayer, but most importantly, I am an aggrieved Indiana farmer because I know the hazard of hog waste first hand. I know that giving the Indiana Department of Environmental Management and Department of Natural Resources directive to protect the state’s environment [while also] increasing the number of confined animal feeding operations (CAFOs) in the state is counter-effective, particularly if additional funds for enforcement are not made available at the same time.”

Not one to just complain, Mr. Warner provides a list of changes that would help prevent more damage:

“Here are some specific examples that I believe would strengthen [any state’s] CAFO laws: First, the state could impose greater setback laws, of at least a mile, from residences, schools, businesses, churches, parks, and other places. Those setbacks should include all confined feeding operation (CFO) structures and land application activities. Additionally, there should be greater setbacks from lakes, streams, wetlands, and other environmentally sensitive areas. Second, the state could also strengthen its factory farm laws by setting air pollution limits for CFOs to restrict their emissions of hydrogen sulfide, ammonia, amines, volatile fatty acids, and other odorous compounds. Third, Indiana should prohibit construction or expansion of CFOs in karst areas and flood plains. Fourth, the state should impose the same public notice and commenting requirements for CFO permits as it requires under the Clean Water Act and Clean Air Act for other industries, which would require IDEM to actually consider and respond to public comments in its decision making on whether to issue a permit. Finally, Indiana’s factory farm laws could be improved with the repeal of Senate Enrolled Act 186, passed in 2014, which requires all Indiana statutes to be construed to protect CAFOs.”

As is seen in Indiana, Arkansas has weak regulations and even weaker enforcement. We also have karst topography that makes it easy for pollution to reach the water table. In the Ozarks, we have hills and valleys, so a 100′ buffer zone around streams, sink holes, springs, and wells without considering the sloping topography makes even less sense. As Mr. Warner noted, our state’s Department of Environmental Protection seems more focused on protecting the rights and opportunities for big business to pollute than doing their stated job of protecting the environment.

The fact that the Buffalo River is also a national park, endowed with all the federal protections that a national park should enjoy, having been set aside by an act of Congress to be preserved for all of us, makes the lack of oversight and care even more incredible. If we are willing to pollute our most extraordinary and treasured waterways, can we expect any of our lakes or rivers to receive the level of protection they so clearly need?

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/692/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

Lin Wellford has made her home in the Ozarks for more than 40 years. A retired author/artist, she now devotes her talents to environmental issues and community causes.

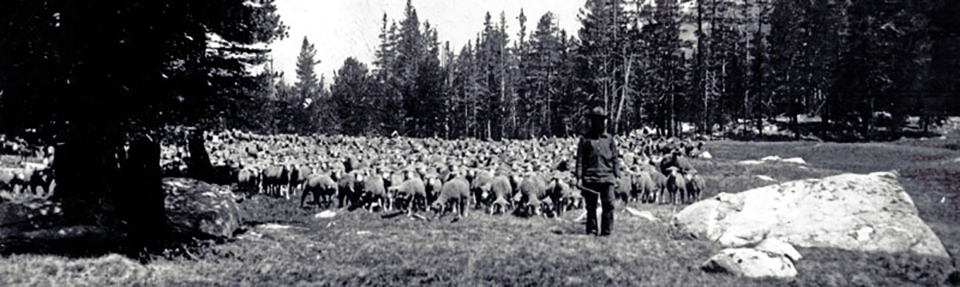

“The Kern Plateau, so green and lovely on my former visit, in 1864, was now a gray sea of rolling granite ridges, darkened at intervals by forest but no longer velveted with meadows and upland grasses. The indefatigable shepherds have camped everywhere, leaving hardly a spear of grass behind them.”

– Clarence King, a member of the Whitney Survey in search of the highest peak in the United States

This past summer, the headwaters team in California was busy assessing wilderness meadows in Kings Canyon National Park. On our last six-day backpacking excursion, we waded through remote meadows perched at 9000 feet, a rugged four miles as the crow flies from the closest trail and ten miles from the nearest potholed dirt road. Throughout the trip, I couldn’t stop wondering about the shepherds and their flocks whose legacies still haunt even the most remote glacially carved canyon in the Sierra. I marveled at their fortitude; lacking such modern luxuries as GPS units, Gore-Tex hiking boots, and titanium trekking poles, these rugged mountain men navigated nearly every nook and cranny in the Sierra Nevada. Though the extreme lengths these shepherds went to are impressive to the modern backpacker, the ecological legacy of sheep grazing is less than admirable. Many Sierra meadows are in poor shape because of the shepherds and their sheep.

Why flock to mountain meadows?

Why did the shepherds traverse rivers and ridges high in the Sierra Nevada in search of remote meadow pastures? A series of floods and droughts from 1862-1864 drove shepherds from the southern San Joaquin Valley to look for higher pastures in the mountains, desperate for a reliable source of forage for their animals. As California’s population grew, so too did the demand for meat. Peak grazing in the park occurred from the late 1800s to the mid-1900s. The transhumance – the movement of livestock from one grazing ground to another in a yearly cycle, from lowlands in the winter to high mountains in the summer – became an established tradition in the Sierra for nearly a century. Even after grazing was banned when Sequoia and Kings Canyon became a jointly operated park in 1940, the impacts of overgrazing are visible today.

Meadows Today

California’s mountain meadows act like sponges – absorbing water during the wet season and slowly releasing it over the dry summer and fall months. In the context of climate change, meadows are an essential component of California’s water supply. As years go by and climate change continues, Californians will likely see less and less snowpack in the Sierra Nevada. Thus, our state will be ever more reliant on healthy meadow systems that act like water reservoirs. In addition to being critical for our future water supply, meadows are biodiversity hotspots and a valuable aesthetic resource.

Why Are Sheep So Baaad?

Overgrazing fundamentally alters how water flows in meadows. In healthy systems, wide stream channels slowly meander through the meadow. However, when meadows are overgrazed, sheep trample stream banks and wipe out the vegetation that stabilizes soil during spring flooding. Without vegetation to anchor down soil, there is widespread erosion and gullying of the stream channel. Once erosion takes hold, spring floodwaters no longer spread out across the meadow surface. Instead, the downcut channel concentrates the energy of high flows, causing a continuous cycle of degradation. When meadow streams incise meadow soils, forming narrow deep channels, the meadow surface dries up. Unhealthy meadows have decreased value in terms of biodiversity, water storage, and aesthetics.

The Role of American Rivers

AmeriCorps member Rachel Friesen and American Rivers volunteer Carson Clark measure a large gully as part of a meadow assessment in Kings Canyon National Park. | Maiya Greenwood

The American Rivers team in California is excited to be partnering with the National Park Service for the first time. Our California Headwaters Conservation team is in the process of performing meadow assessments in order to prioritize wilderness meadows for restoration. Over the last summer, our team has trekked many miles across boulder fields and through aspen thickets to access meadows in remote reaches of the Sequoia-Kings Canyon Wilderness. Currently, we have completed 42 out of the 50 meadows that we aim to assess by 2018. Following the initial assessment phase, we will continue to partner with the National Park Service by piloting meadow restoration techniques that are appropriate in wilderness areas.

We hope to pull the wool off our eyes and not be fooled into thinking that remote wilderness meadows are inherently pristine. Here at American Rivers, we know that some systems are not resilient enough to recover on their own; many wilderness meadows need both time and active restoration efforts to heal after a century of overuse.

This guest blog by Ginny Masullo is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series on the Buffalo National River.

“Sentiment without action is the ruin of the soul” – Edward Abbey

I moved to Northwest Arkansas in 1974. My soon to be landlord had been one of the many unsung heroes responsible for the Buffalo River not being damned and becoming our nation’s first national river. She pointed us to the Buffalo and said “go!”

A young mother from urban Texas, the land of asphalt and more asphalt, I had never experienced hiking along or padding down a river as clean and pristine as the Buffalo. The Buffalo River and its trails soon became the respite from a demanding livelihood in nursing.

Who can possibly explain what places like the Buffalo River do for our souls? All I know is that something akin to a cleansing happens when I go to the wild. On the river, time does not exist – only the sound of the rushing water, the cries of the wood thrush and crow and the sight of light dancing on the water.

Now a retired nurse, I see how the Buffalo River played an almost inexplicable role in my life in the repeated healing of the sorrow of daily dealings with chronic illness and death. Trips to the river alone and with family fueled me again and again to return to my work.

I have seen numerous changes in my 40 years visiting the river including an increasing congestion of paddlers. This is fixable by limiting the number of paddlers.

However, there are other threats to the Buffalo River not so easily remedied. Not small among them is a 6,500 hog factory farm within its watershed. When I learned of this hog factory (which had been permitted without public notice), I decided to help with an awareness raising event. Having just retired, at the time I would commit to only that event, then I planned to be on my merry way to paddling and hiking adventures.

However, the more I learned about factory farming and the destruction it had already wreaked in North Carolina and Iowa, the top two hog producing states, the more I felt compelled to work to save a river who had metaphorically breathed life into me over and over.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/692/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

Ginny Masullo is a retired RN and a passionate advocate for the environment. She brings a caregiver’s heart and a poet’s eye to all the issues she devotes herself to.

This guest blog by Lin Wellford is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series on the Buffalo National River.

Once upon a time, we could all agree on what it meant to ‘sustain’ something. It meant achieving a balance that could be maintained over time. Healthy natural systems are the template for establishing sustainable practices.

In Europe, where people lived and farmed long before the “New World” was discovered, sustainability is mandated by limited resources and dense populations. Historically, farmers have been the masters of sustainability, striking a careful balance between what they put into the soil and what they could expect to take from it in the way of crops. Farmers were the original environmentalists, because they were the first to see that maintaining a careful balance allowed them to grow healthy crops year after year.

A couple of summers ago, the EPA was criticized for accidentally breaching an earthen dam, releasing mine waste from a leaking storage lagoon into a local river. The waste turned the waterway a startling yellow-orange hue that stained the rocks along the shore long after the polluted spill had moved down river. But why was the waste-filled lagoon left behind for a taxpayer-supported government agency to deal with? It’s the same old story— once the company extracted the value and profit from the mine, they declared bankruptcy and just walked away, leaving all of us with their mess.

Thirty years ago, as untapped natural resources began to get harder to find, restless corporations started to focus on a new profit center: food. People had to have it, and because farmers were historically good stewards of their land, there weren’t a lot of regulations in place to restrict operations. In short order, independent farmers found themselves being shut out of the meat market, with no way to sell their poultry or hogs.

But, surprise! Corporations soon came along with a friendly proposition for the very folks they’d just run out of the business.

First it was contract chicken and turkey growers, who raised the birds, but did not own them, and settled for a slender slice of the profits. To make a decent living, contract growers have to take on huge debt and build more poultry houses. It is also their part of the deal to dispose of the waste.

Hogs were a little trickier. They are large mammals, and can really produce a lot of waste. And again, the contract grower will own that waste although he will own not one of the thousands of pigs he feeds and houses.

Already the EPA reports that agricultural waste from these kinds of industrial operations are a leading cause of impaired waterways. Eventually, the evidence will be beyond dispute. But for now, weak regulations and lack of enforcement are allowing concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) to wreck our rivers.

Do we really have to wait until every precious river and stream in the country is unfit for human use before we stop the pillaging, and then raise taxes just to clean up the mess?

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/692/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

Lin Wellford has made her home in the Ozarks for more than 40 years. A retired author/artist, she now devotes her talents to environmental issues and community causes.

Last week, the state celebrated the second anniversary of Colorado’s Water Plan. Over the last two years, the state has made solid progress funding grants to advance water projects and increase funding for stream management plans. However, the challenges identified in the plan are significant. A swelling population is stretching our water resources, and climate change is having an impact, by reducing flows on the Colorado River. We need to pick up the pace toward implementing all of the Plan’s water solutions if we are to reach our goal of securing clean reliable water for our communities, preserving our agricultural heritage, and protecting our rivers. Over the next few months, We Are Rivers will highlight the Colorado Water Plan through a series of episodes breaking down the opportunities, challenges, and successes to date from Colorado’s Water Plan. Join us for the first installment, as we look back at the last two years of the water plan and identify a sustainable path forward.

Growing up in New York, I envied the posters pinned up in my middle school hallways that honored Colorado landscapes like the Maroon Bells, Dinosaur National Monument, the Great Sand Dunes, and of course the Colorado River as it weaves through canyons and deserts. But moving to Colorado six years ago, tacking on to Colorado’s growing population, I haven’t exactly made life easier for the state’s water managers. Without the native badge, I empathize with the influx of people flooding into Colorado who have recreational fervor, career hopes, and of course adventure in mind, straining the West’s already overtapped water supply.

Colorado’s population is projected to double by 2050, with most of the growth occurring on the Front Range, where about 80% of the people live. With about 80% of the state’s water coming from west slope snowpack, the imbalance is striking. Additionally, like many other states across the Southwest, Colorado is experiencing higher temperatures, reduced precipitation, and earlier and faster runoff. With growing population and climate change impacts, how can Colorado work to close our gap in supply and demand? Through increased collaboration, dialogue, and efficiencies, the Colorado Water Plan sets out to address this grand dilemma.

The Colorado Water Plan sets a goal of conserving 400,000 acre-feet of municipal and industrial water by 2050. By 2025, if the Water Plan objectives are met, 75% of Coloradans will live in communities that have water-saving actions incorporated into land-use planning. Furthermore, by 2030, the plan sets out to A) re-use and share at least 50,000 acre-feet of water amongst agricultural producers, B) cover 80% of locally prioritized rivers with Stream Management Plans, and C) ensure 80% of critical watersheds with Watershed Protection Plans. In order for a project to utilize the Water Plan’s budget to meet these goals, the proposed conservation project must be appropriate in that it addresses real needs and is cost-effective, sustainable, and supported by local stakeholders.

The state has taken a great step forward by allocating $10 million per year for Water Plan Implementation grants. While this is a first step, we must further fund the plan’s broader strategies as well. Public investment in water projects must be smart, which starts with meeting all of the “criteria” in the Colorado Water Plan. Before any new, significant projects are proposed, the state should apply all of the Water Plan’s criteria in order to demonstrate that the state is committed to investing in (or endorsing) only projects that use public resources wisely, protect rivers and wildlife, and reflect community values. The last two years have seen state funding disproportionately spent on costly structural projects while sustainable, cost-effective methods, such as water reuse and flexible water-sharing agreements have been undervalued and underfunded. Creative conservation projects are essential in upholding the Water Plan to sustain the natural beauty of Colorado’s rivers and streams and ensure a safe and reliable drinking water supply.

However, it is important to note that there is nothing legally binding in the Water Plan that requires Colorado to abide by its outlined goals. Therefore, the success of the plan solely relies on the motivation of everyday people to work together as a community to hold politicians and basin roundtables accountable with respect to the plan. I encourage you to learn more about where your water comes from and what you can do as an individual to reduce your water consumption. We all need to work collaboratively to reduce our demand for water.

As we celebrate the second anniversary of Colorado’s Water Plan, we have an opportunity, and a responsibility to rally behind the premise of the Plan, keeping Colorado beautiful and sustainable for all. Join us over the next few months as we dive into the mechanics of Colorado’s Water Plan, and why it is so important to see it succeed.

This guest blog by Lin Wellford is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series on the Buffalo National River.

How would you react if a neighbor did something that suddenly altered your quality of life or the value of your property?

For too many folks in a rural areas, this isn’t just a rhetorical question. People who live in the country understand the realities of farming and raising animals. They know that in the spring, cattle growers may get a load of chicken litter applied to their pastures to help the grass grow, and the smell will be noticeable for a few days. Sometimes animals get out in the road and it’s neighborly to alert their owner. You might get stuck behind a slow-moving tractor now and again.

That’s life in the country. People look out for each other. They try to get along and be considerate.

If a neighbor decided to build a rural factory, complete with constant truck traffic in and out, plus industrial sounds and smells (very unpleasant smells at that, and not just a few times a year, but nearly year-round)… what would you do?

Neighbors surrounding an industrial-scale hog operation in tiny Mount Judea, Arkansas, have been living this new reality since discovering that a local man bought property up on a hill in the heart of their community. The factory turns out piglets by breeding 2500 sows in rotation, producing something like 80,000 animals yearly. The owners and proponents call it a farm.

Officially, it is classified as a confined animal feeding operation, or CAFO for short. In other words, it’s an indoor feedlot for pigs. Two giant metal buildings stand windowless, with exhaust fans running around the clock to keep the enclosed hogs from suffocating. The animals never see daylight, except through the slats of a truck transporting them to the facility where they will be finished, meaning fattened, before being shipped one last time to a slaughter house.

As someone who used to enjoy bacon and a good barbequed spare rib, learning about how pork is now mass produced was a real eye-opener. It is well known that pigs are as smart, perhaps even smarter, than many dogs. Yet these CAFO animals spend their entire lives either pregnant or nursing babies, within metal confinement pens inside these buildings.

The pig, who is curious and playful under normal circumstances, never experiences the sun on its back or ground under its feet.

The cement floors have metal grates, allowing waste to accumulate in a pit beneath the building. The floors are washed off at intervals and the pits are emptied into outdoor lagoons (basically open sewage ponds). From there the waste these animals produce, over 2 million gallons a year, is pumped into trucks and taken to a patchwork of fields where it is sprayed out onto the ground as often as possible.

Neighbors complain privately about the smell, the flies, and the traffic as the spray trucks make their circuit from the sewage lagoons to the fields and back. But no one complains too publicly. No one wants to be a bad neighbor.

In Pennsylvania, a family farm that operated for generations switched to this industrial model of mass producing swine. The neighbors had a year to make formal complaints, but they liked their neighbors and trusted them. The farmers, in turn, trusted the corporation that assured them this was a safe and efficient way to make a good living.

It was only after a year of operation that the constant presence of sprayed manure was impossible to ignore. By then, Pennsylvania law said nothing could be done. One neighbor found that she could not keep her swimming pool water clear after numerous treatments. Finally the pool tech asked if there was a CAFO in the area. She told him there was. He shrugged and said there was no way to counter the effects of airborne pollutants.

If what is in the air is messing up pool water, what is it doing to our rivers and streams, not to mention our lungs?

Many states are passing laws to protect landowners’ ‘right to farm’, even though the definition of farming has been altered radically in the past few decades. Shouldn’t neighbors also have the right to protect their way of life from being ruined by one landowner‘s choice to turn his farm into a factory?

The operators of these facilities don’t even own the animals under their care. But they do own the manure that is left behind and many find that the fields used to dispose of waste rapidly accumulate more nutrients than they can use. The result over time is often hay that is too high in nitrogen to make healthy fodder. Excess nutrients also find their way into the water table, impacting private wells and, eventually, local waterways.

Environmentalists are scolded for their reaction to having such an over-sized operation placed in fragile, environmentally sensitive areas. But the fact is that similar CAFOs have a history of polluting groundwater and rivers. The corporations will deny this up to the moment that the evidence becomes irrefutable. Contract growers will be left holding the mortgage for the facility, and the public will be on the hook to clean up the mess, while the corporation moves on to find another poor rural area in a state with lax environmental laws they can take advantage of.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/692/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

Lin Wellford has made her home in the Ozarks for more than 40 years. A retired author/artist, she now devotes her talents to environmental issues and community causes.

How do you save a river running dry? One creek at a time.

That’s the spirit of the Upper Flint River Working Group – a voluntary, collaborative forum in which conservation groups, water utilities, and other stakeholders come together for open dialogue on how to restore drought resilience to one of the region’s most important rivers.

Twice a year, in a meeting room at a Methodist church in a bucolic setting on the edge of the Georgia countryside, the Working Group gets together for the better part of an afternoon. We talk about the year’s weather (and its impact on the river), about key challenges in conservation on the Flint, about new opportunities for partnership, and we share updates about ongoing projects throughout the basin.

One of those projects is on Flat Creek in Fayette County, where the county water system director is leading an effort to better manage reservoirs to sustain both his water system and its downstream neighbors for the future. While the water system has already taken on the low-hanging fruit of improved management practices, American Rivers is working closely as a partner to provide science-based recommendations for long-term sustainable management. We don’t know when the next drought will strike the Flint, but we do know that this team effort is already resulting in a healthier Flat Creek and will result in a healthier Flint River, too.

[su_button url=”https://www.marketplace.org/2017/07/27/sustainability/in-era-water-ownership-sparks-disputes-georgia-water-agency-share-supply” background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Listen in for more »[/su_button]

Almost one year ago, I conceived the idea to run across South Carolina, all in the name of river and freshwater resource conservation. I reached out to American Rivers early in the process and they were excited to partner with me. We named the project Running For Rivers, and later came to an agreement with RES, LLC to be the presenting sponsor. I am a biologist and ultra marathon runner, and have been working and running in South Carolina for many years. For work, I focus on the conservation and management of freshwater, estuarine, and marine resources. In my running life, I love to get out in the wilderness and try to run next to rivers and streams; it brings me peace and great joy to run next to flowing water. This project truly brought together two of my greatest passions.

Over the year of route planning and logistics, it was clear that the route was going to be close to 300 miles. I made the decision to round it up to an even 300 miles. I then decided to attempt to tackle the 300-mile journey in 3 days (72 hours). Very few people have ever accomplished that distance in that time, but it is always important to dream big and go after goals that may seem “impossible.” Additionally, “300 miles in 3 days” had a nice ring to it.

On Thursday Nov. 2 at 10:07 in the morning, I began running toward the ocean from the NC/SC Border (Eastern Continental Divide), near the Middle Saluda River. After about 8 miles, it was apparent to me that something was wrong. I had trained for 4-6 months, but I was feeling fatigued and my quads were already hurting with 292 miles left. At about mile 10, I left a quiet gravel road and stepped onto a very busy 2-lane secondary highway where vehicles were flying by me, barely giving me an inch. Much of the next 2 days were characterized by few sidewalks, lots of traffic at high speeds, and generally just feeling “off.” The constant onslaught of high-speed traffic (often with distracted drivers) was much more draining than I had anticipated.

On Thursday Nov. 2 at 10:07 in the morning, I began running toward the ocean from the NC/SC Border (Eastern Continental Divide), near the Middle Saluda River. After about 8 miles, it was apparent to me that something was wrong. I had trained for 4-6 months, but I was feeling fatigued and my quads were already hurting with 292 miles left. At about mile 10, I left a quiet gravel road and stepped onto a very busy 2-lane secondary highway where vehicles were flying by me, barely giving me an inch. Much of the next 2 days were characterized by few sidewalks, lots of traffic at high speeds, and generally just feeling “off.” The constant onslaught of high-speed traffic (often with distracted drivers) was much more draining than I had anticipated.

Ultimately, I pushed hard and grinded through some rough miles and a lot of pain, all while passing near or over the South Saluda, Reedy, Little, Bush, Broad, Congaree, and Saluda Rivers. I made it 150 miles to Columbia, SC in about 53 hours. After very tough circumstances and heavy heart, I made the decision to stop. The 150 miles would have been impossible without my amazing crew and pacers, which included my fiancé Laura and her cousin Mel, my endurance logistics masters Lauton and Kenny, ultra-running maniacs Justin and Andres, and communications director Dan. I would not have been able to make it more than 20 or 30 miles without the crew; they were truly amazing.

Additionally, the adventure would been extremely tough without all of the support and generosity from RES, American Rivers, Badwater, Orvis, NipEAZE, Crevar Chiropractic, and all of our other sponsors.

I guess we will call this Running For Rivers Part 1. Stay tuned for Part 2…

Learn more about Keith’s adventure at www.RunningforRivers.com

Ushering in a new chapter for the Neuse River and City of Raleigh, removal of the unsafe and obsolete Milburnie Dam began on Wednesday, November 15.

Why dam removal?

This obsolete dam hadn’t produced power in years and much worse, it had caused the death of 15 people, who drowned in the hydraulic created at the abandoned powerhouse. Removing the dam eliminated this public safety hazard. It will also restore the health of the Neuse River.

What benefits will the dam removal bring?

Milburnie Dam was the last impediment to migratory fish on the Neuse River from the coast, particularly shad and striped bass. The six mile long impoundment will return to its free flowing state and fish will return to their historic spawning grounds. As a part of the project, 7 years of monitoring will be performed to see how the biological and physical characteristics of the river change after dam removal. The Neuse will not only benefit from the removal of the dam, but the site of this project will be protected in perpetuity under a conservation easement.

American Rivers has advocated for the removal of Milburnie Dam for over a decade. Restoration Systems is managing and funding the project with private dollars. Mitigations credits will be generated by this project into a mitigation bank. This dam removal is the continuation of a comprehensive river restoration effort, including four previous dam removals downstream and on Neuse River tributaries.