We all know that Arizona lies in a big, dry, desert – yet we still love living here and making this state our home! But the beautiful landscape and economic vitality that supports the unique Arizonan lifestyle is fueled by our supply of water, and that supply is in jeopardy. Nearly half of Arizona’s water is provided by the Colorado River via the Central Arizona Project (CAP) canal. That’s drinking water for people, irrigation water for farms, ranches, and wineries, water for businesses and towns that keep Arizona’s economy humming, and water for our abundant wildlife and natural heritage.

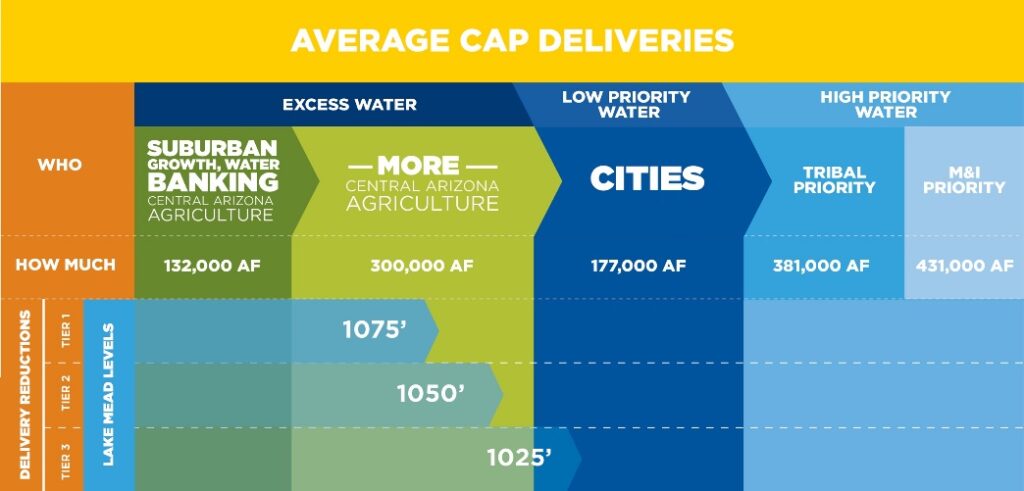

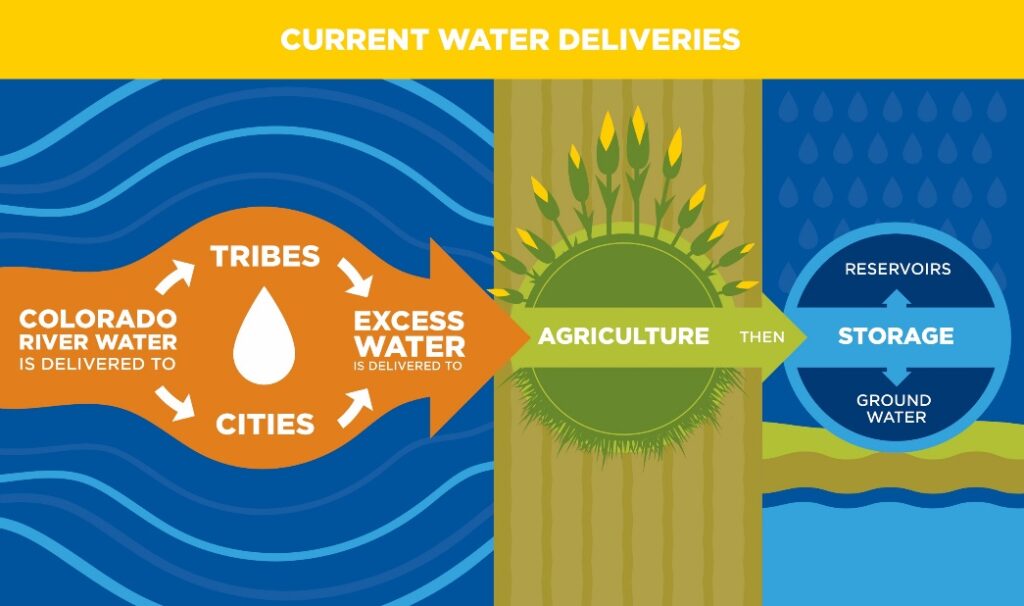

CAP Water that is unused by Arizona tribes and cities gets passed to other uses

Our supply of Colorado River water is measured and managed by levels in Lake Mead, on our northern border with Nevada. Due to drought and dramatic overuse in the Southwest, Lake Mead has been dropping quickly, even with hefty snowpack in Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming over the past few winters – the mountains simply cannot keep up with overuse by Arizona and surrounding states.

Our supply of Colorado River water is measured and managed by levels in Lake Mead, on our northern border with Nevada. Due to drought and dramatic overuse in the Southwest, Lake Mead has been dropping quickly, even with hefty snowpack in Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming over the past few winters – the mountains simply cannot keep up with overuse by Arizona and surrounding states.

Built in conundrum: more water is taken out of Lake Mead than comes in each year

This imbalance is why leaders and elected officials from California, Arizona, and Nevada, along with the U.S. and Mexican governments, have come together to negotiate a deal that will work hand-in-hand to store more water in Lake Mead, and will ensure participation from each of the states on a formal basis. This agreement is called the Drought Contingency Plan, or DCP, and we need to get it done!

Under Bureau of Reclamation operating guidelines for the river, Lake Mead must be maintained at an elevation of at least 1,075 feet, and in recent years with a combination of overuse and the effects of drought, the lake has barely stayed above that level. If it drops below 1,075 feet, mandatory cutbacks could be first imposed upon Arizona, with other states being penalized later. Deeper cuts are possible if the lake level drops further.

CAP Provides Water for Many Uses. Without DCP, Shortages Could Touch All Arizonans

These cuts would create significant risks, especially for the agriculture and development sectors of our state’s economy who will be the first to see their water supplies reduced. The impacts wouldn’t be evenly felt; some communities and natural resources would suffer more than others.

A DCP Agreement is Necessary to Prevent Undesirable Consequences

No great feat of engineering is going to help us out of this predicament – however our ingenuity can help us find a way. Instead we must look to policies and conservation measures governing water use in the lower Colorado River Basin. The DCP does just that by forging a series of agreements, enforceable between the three states, to share investments in these conservation measures, as well as the benefits. The DCP will balance our water system and make us more resilient to future shortages, as well as provide a mechanism for future agreements to secure sustainability across the entire southwest. It is truly a win for Arizona, and a path forward for all three states.

No great feat of engineering is going to help us out of this predicament – however our ingenuity can help us find a way. Instead we must look to policies and conservation measures governing water use in the lower Colorado River Basin. The DCP does just that by forging a series of agreements, enforceable between the three states, to share investments in these conservation measures, as well as the benefits. The DCP will balance our water system and make us more resilient to future shortages, as well as provide a mechanism for future agreements to secure sustainability across the entire southwest. It is truly a win for Arizona, and a path forward for all three states.

When implemented, the DCP will do five key things:

1) Protects Arizona water users from drastic, involuntary reductions, and provides for gradual reductions through voluntary water exchanges and conservation.

1) Protects Arizona water users from drastic, involuntary reductions, and provides for gradual reductions through voluntary water exchanges and conservation.

2) Encourages the three states, with additional help from the country of Mexico, to voluntarily keep more water in Lake Mead, working together to avoid dropping below the 1,075 feet elevation threshold.

3) Joins all three states (and the U.S. government) in collective responsibility to protect Lake Mead’s water, especially if lake levels continue to drop – and provides for the first time that California will share in some of the water reductions.

4) Provides incentives for states, especially California and Arizona, to store some of its extra water, known as “surplus” or “excess” in Lake Mead, when it has it. As states conserve more, and with the blessing of abundant winter snows, Lake Mead can rise again – especially if we help it do so.

5) And lastly, the DCP works towards a collaborative management solution between the states and federal government, with the health of Lake Mead as a top, stated priority.

Legislation is Needed in 2018 to Improve Arizona Water Management in Three Areas

1) Support the Drought Contingency Plan (DCP): The Lower Colorado Basin DCP is a proposal currently under consideration that aims to protect Lake Mead’s elevation from dropping to critical levels that would reduce Arizona’s water supplies. The Coalition is working to get it authorized by the Legislature and signed by AZ, CA, NV and the Bureau of Reclamation.

2) Support an Arizona DCP-Plus Plan: DCP-Plus is an Arizona-only plan to keep Lake Mead elevation above 1,080’ and delay or prevent future shortage declarations that could take out roughly one-third of Central Arizona’s Colorado River supplies. DCP-Plus would incentivize reductions in water use and water storage programs so that unused water can be safely stored in Lake Mead. To enact the Plan, the Coalition believes we need an ‘Excess Water’ compromise that helps both the River Counties where CAP seeks to buy and transfer new water supplies, and for others who depend on the economic vitality created by a secure Colorado River supply.

3) Support an Arizona Colorado River Conservation Plan: Such a plan would establish an ongoing and collaborative process to ensure Lake Mead elevations are always protected. The plan would estimate conservation volumes needed on a yearly basis to ensure Lake Mead elevations do not fall to the point at which Arizona will experience harmful shortages. The Coalition supports a plan that would assure water users that the water they choose to forbear and conserve in Lake Mead will benefit all Arizonans, and not be consumed by another water user.

The deal is not final yet. Completing DCP negotiations is key to protecting Lake Mead from future shortages. And most importantly, it reminds residents and business interests across all three states that we are all in this together, and by acting boldly, we can sustain our lifestyle, economy, and rivers and wildlife of the Southwest for generations to come.

For more information on broader Colorado River issues in the lower basin, please visit our Lower Colorado webpage.

Everyone deserves access to safe, affordable, reliable clean water. Unfortunately, in communities across the country, clean drinking water is at risk. That’s in part because our water infrastructure – including pipes to distribute drinking water and move dirty water to treatment systems – is outdated and in some cases, literally crumbling.

Last year, the American Society of Civil Engineers issued a report card on the nation’s infrastructure. Drinking water systems received “D” grades. And while this puts all Americans at risk, it’s communities of color and lower-income neighborhoods which already suffer from lack of investment and opportunity that feel the worst impacts.

We must bring our water infrastructure up to modern standards – our health, economy and well-being depend on it. The Environmental Protection Agency has estimated that we need more than $650 billion in water infrastructure investment over the next 20 years just to meet current environmental protection and public health needs.

President Trump is making infrastructure a focus of his State of the Union address on January 30 and he is expected to release a plan for the nation’s infrastructure in the coming weeks. Any successful plan will make real investments in repairing aging water mains and replacing lead pipes, not just offering corporations tax cuts and privatization schemes or rolling back bedrock environmental laws like the Clean Water Act.

It’s also critical that when we invest in water infrastructure, we invest wisely. While fixing old pipes must be on the “to do” list, we should also prioritize nature-based solutions to managing our water resources. These innovative approaches not only deliver clean water, they have multiple benefits for communities – saving money, creating jobs and improving lives.

Nature-based solutions can mean planting trees and restoring wetlands, rather than building a costly new water treatment plant. It can mean choosing water efficiency and conservation instead of building a new water supply dam. It can mean restoring floodplains instead of building taller levees.

These approaches that protect, restore and mimic the natural water cycle have a wide range of social, economic and environmental benefits. Our report “Naturally Stronger” documents how cities including Philadelphia, Milwaukee and Washington, DC are successfully using nature-based solutions to secure reliable water supplies, create good jobs, keep water rates affordable, increase community parks and green space, and reduce flooding.

As President Trump puts infrastructure in the spotlight, American Rivers will be urging Congress to reject the President’s proposals to weaken bedrock environmental laws such as the National Environmental Policy Act, Endangered Species Act, and Clean Water Act. We will also encourage Congress to stand up for greater water infrastructure investment and insist on nature-based solutions to restore and modernize our nation’s infrastructure.

This week the president delivers his annual State of the Union address to Congress. Doubtless President Trump will declare that due to his efforts the state of the union is strong, and assure Americans that whatever problems remain, he – alone – will fix them. But to those who care about rivers and clean water (which should be everyone, right?), those assurances will ring hollow.

Rivers and streams in America have come a long way since the dark days when oily plumes of smoke rose over the burning Cuyahoga. Federal legislation like the Clean Water Act and the Safe Drinking Water Act have dramatically reduced pollution – by one estimate, the dumping of toxic pollutants by industry has been reduced by 700 billion tons per year – slowed the destruction of wetlands and small streams, and helped make drinking water supplies in the U.S. among the safest and most reliable in the world. But (and there’s always a “but”) the job of securing the nation’s water resources from pollution and environmental degradation is far from finished.

The Clean Water Act (CWA) set a goal of making the nation’s waters “fishable and swimmable” by 1983. Though we’ve made significant progress, we missed that deadline by a wide margin. According to one recent study, over 50% of assessed rivers and streams failed to meet water quality standards. In another, only 28% of rivers and streams were determined to be in good condition while 46% were in poor condition. Nearly 25% of river and stream miles nationwide carry harmful bacteria at levels that could threaten the health of people exposed via recreation. Wetlands continue to suffer from pollution, dredging and filling. In fact, recent studies suggest the pace of wetlands loss has been increasing since the early 2000s.

In the latter half of the 20th century, the dependable quality of drinking water in the U.S. was the envy of the world, but after years of neglect, cracks are appearing in the legal and physical infrastructure that we all depend on for safe drinking water. Pollution from lead, coal ash, algae blooms, agricultural run-off, and other sources are fouling water supplies in communities across the country. The American Society of Civil Engineers gives the condition of the nation’s wastewater and drinking water infrastructure a grade of D-, and the American Water Works Association estimates that a trillion dollars over the next 25 years is needed to make the system whole again. No less an authority than the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency warned (during the previous administration) that crumbling infrastructure threatens to reverse the public health and environmental gains achieved since passage of the Clean Water Act.

President Trump is unlikely to dwell on much of this in his State of the Union address. But his actions, and those of his EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt, speak volumes about the administration’s lack of concern for clean water and its antipathy toward federal efforts to protect it. The new administration was barely under way before plans were announced to drastically cut the EPA’s budget, and long-time agency professionals and advisors – the core scientific expertise and institutional memory of the agency – found themselves frozen out of decision-making. One of Trump’s first acts as president was to sign a bill revoking an Obama Administration rule that would have stiffened limitations on the dumping of mine waste into rivers and streams. Since then the administration has announced plans to review (read: roll back) a rule that protects streams from the dumping or leakage of coal ash, scrapped a policy that required that planning of public infrastructure projects account for flooding aggravated by climate change, and delayed compliance with a rule limiting the discharge of water-borne pollutants from coal-fired power plants.

Plans were laid even before the inauguration to eliminate the “Waters of the United States” or Clean Water Rule. In 2001 and 2006, two oblique Supreme Court rulings cast doubt on the extent of the CWA’s jurisdiction, and the Obama Administration engaged in a lengthy rulemaking process to clarify the authority of the CWA to protect small streams and wetlands that contribute to the drinking water supplies of one in three Americans. After years of painstaking scientific, economic and legal analysis, hundreds of public meetings, and a comment period that produced over a million comments, the Clean Water Rule was adopted, reaffirming the CWA’s authority. Shortly after taking office, President Trump and Administrator Pruitt launched an effort to sweep away this carefully crafted rule and once again expose hundreds of thousands of miles of small streams and wetlands to unregulated pollution and degradation.

So, at a time when action to protect the nation’s water resources should be ramping up – according to a recent poll the public’s concerns about clean water are at their highest level in over 15 years – the Trump Administration is doing exactly the opposite. And don’t let the Administration’s much ballyhooed initiative on infrastructure (which the president may tout in his speech) fool you. A draft of the plan that began circulating a few days ago reveals it to be an industry wish list of exemptions from the nation’s bedrock environmental laws that would further undermine protection for rivers, streams and clean water.

If that sounds bleak…well…it is pretty bleak. Fortunately, folks all over the country are rising to meet the challenge of protecting rivers and clean water despite the headwinds created by a president hostile to environmental protection. American Rivers and allies will challenge the rollback of the Clean Water rule in federal court, arguing that the administration’s effort to sweep away the rule is not only unwise but unlawful. States from California to Maryland are investing in water infrastructure the right way, with dam removal and river and floodplain restoration projects that promote water quality, improve public safety, and provide wildlife habitat and recreational opportunities. Partnerships between landowners, NGOs, local governments and Native American tribes are implementing watershed restoration and management projects that benefit local communities as well as fish and wildlife. Cities across the country are pioneering integrated water management approaches to secure drinking water supplies and better manage pollution from sewer overflows and urban run-off. Stakeholders are working together to better allocate scarce water resources in response to drought, and promoting natural infrastructure – rivers floodplains, and wetlands – that can often be as effective as concrete and pipes at purifying and delivering drinking water to communities, and at a significantly reduced cost.

None of this can replace an active federal government promoting strong protection for rivers and clean water and investing the billions of dollars necessary to effectively address the decay of our water infrastructure. Until we return to that kind of federal leadership, we must do everything we can to hold the line for rivers and clean water.

This is a guest blog by our January 2018 National River Cleanup intern, Chelsea Alley.

There is a wide variety of trash found at river cleanups; from shopping carts to sofas, bottles to baby dolls. National River Cleanup® volunteers work to make these waterways trash-free – removing unique and common items alike. In no particular order, below are the five most common trash items found at river cleanups:

1. Cigarette butts

Cigarette butts weigh one gram or less, but they account for 30% of all litter in the United States. They are the single worst offender in spite of their small size (food packaging makes up a larger percentage of litter but includes more than just one item, like straws, takeout containers, snack wrappers, etc.). This means that more than one trillion cigarettes are discarded each year, weighing over two billion pounds… or the equivalent of 42 Titanic’s stacked together!

2. Plastic bottles and bottle caps

More than 22 billion plastic water bottles are thrown away yearly, meaning only about one in every six water bottles purchased in the United States ends up being recycled. An average water bottle weighs about 12.7 grams, so the amount of water bottles wasted each year weighs over half a billion pounds. That’s almost as heavy as the Empire State Building! Plastic bottles and bottle caps aren’t biodegradable, but they do photodegrade. That means that this plastic breaks down into small parts in the sun, and releases chemicals into the environment as they disintegrate. The worst part? They continue breaking down for 500 – 1,000 years!

3. Food Packaging

Food packaging is the largest category of waste on this list, as it includes household packaging (i.e. milk jugs, juice boxes, and snack packaging) as well as fast food packaging (i.e. paper, Styrofoam, paperboard wrappings, coffee cups, and drink cups). Almost half of litter in the U.S. is food packaging. While some of these items could be recycled, most are not, and often these are found weighing down shorelines and waterways. The Natural Resources Defense Council estimates that fast food chains and consumer brand manufacturers relying on single-use packaging waste over $11 billion a year, enough to fund ¼ of the U.S. Energy and Environment budget.

4. Plastic Bags

Plastic bags are so common in the United States that over 100 billion bags are used each year. Over three times more bags end up as litter in our forests and waterways than are recycled annually. Plastic bags only weigh about eight grams each, but enough are littered annually to weigh as much as 176 adult blue whales! Plastic bags take almost as long to degrade as plastic bottles, leach chemicals into the environment, and inhibit natural water flows.

5. Aluminum Cans

Almost 100 billion aluminum cans are used in the U.S. annually, and only about half of these cans are recycled. The rest go to landfills or into the environment. Beverage containers account for 50% of roadside litter (though this statistic includes plastic containers), and much of that is washed into our waterways. Every aluminum can weighs about 14.9 grams, which means that even if only 1% of the aluminum cans used each year were littered, there would be enough waste to equal the weight of 2,500 African bush elephants, and enough cans to circle the equator almost two and a half times.

Bonus: What will stay in your river the longest? Microplastics.

Microplastics can come from larger plastic items when they break down, or in the form of products like microbeads. Most microplastics float into the ocean, but a lot will sink to the bottoms of riverbeds and mix in with the sediment there. This effects oxygen levels in the water as well as harms animals that depend on these ecosystems for their livelihoods. Because plastic takes so long to break down, microplastics are so small, and these items are located along the bottom of rivers, they can stay in the rivers for potentially up to 1,000 years.

These numbers are certainly overwhelming, but they don’t need to stay that way! There are many things you can do on your own or with your community to reduce the amount of waste in rivers:

- Organize a cleanup with National River Cleanup®, or sign up for an existing cleanup near you.

- Learn more about recycling with our National River Cleanup® recycling guide.

- Take our River Cleanup Pledge to pick up trash and help us fill our virtual landfill.

- And more!

Author: Chelsea Alley

Chelsea is a third-year Environmental Studies student at Hollins University and was a National River Cleanup intern for the month of January, 2018.

The Custer Gallatin National Forest, stretching from Southwest Montana to South Dakota, is midway through a four-year process of revising its forest plan. In January 2018, the forest released its “Proposed Action,” which among other things would administratively protect 31 rivers that were found to be eligible for designation under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act: streams that are (1) free-flowing, and (2) possess at least one outstanding value like scenery or recreation. If these rivers make it into the final plan, 278 miles of free-flowing river in the forest would be administratively protected from projects that would alter their free flow nature or outstanding values.

National Forests are required to inventory and protect the Wild and Scenic eligible rivers in the forest when they revise their forest plans – approximately every 20 years – giving people a once or twice in a lifetime opportunity to weigh in. Please submit a comment supporting these 31 Wild and Scenic eligible streams by March 5, 2018, at: cgplanrevision@fs.fed.us with subject line “Comment – draft plan – CGNF” Please recommend that they add the Taylor Fork River (pictured above) as well – it deserves it!

The Custer Gallatin National Forest Plan Revision is just one of many such processes that American Rivers is engaged in to protect wild rivers in celebration of the 50th Anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act in 2018. With our partners, we plan to protect 5,000 miles of wild rivers and collect 5,000 stories. Visit the 5,000 Miles of Wild website to read some of the stories that we have gathered, explore the regions that we are trying to protect, and maybe even share a story of your own. Hopefully you’ll come away inspired to help us celebrate the 50th birthday of the strongest river protection designation in the world.

From the Chena River in Alaska to the St. Lucie in Stuart, Florida individuals and groups got their hands dirty for clean water throughout 2017. This past year, National River Cleanup®:

- Registered cleanups at 1,877 sites,

- Mobilized 65,614 volunteers,

- Removed 3,008,259 pounds of trash, and

- Kept roughly 10,000 pieces of garbage and debris out of our waterways.

Behind these numbers are people – volunteers and organizers who worked tirelessly to ensure our rivers were left cleaner and safer than how we found them.

To honor these individuals and groups, we launched the National River Cleanup River Heroes program in 2016. This year, we brought this recognition program back under a new name (Cleanup Champions) so we can shine a light on all the great work taking place across the country. The categories for this year’s awards were:

- Most River Miles Cleaned

- Most Pounds of Trash Collected

- Most Volunteers Mobilized

- Tiny but Mighty

- NEW: Cleanup to Watch

For each of the first three categories, we crowned a large-scale (ten or more cleanup sites) and a mid-sized (nine or fewer sites) event with the coveted title. In addition, we named a few honorable mentions. Click here to see the full list of winners and honorable mentions.

Curious to learn more about the winners? I reached out to a few to learn a bit more about their cleanups. Check out what they had to say:

The Charles River Watershed Association (CRWA): This group was 2016’s top River Hero for “Most Volunteers Mobilized,” and this year they secured the spot by drawing 100 more volunteers! “For the past 18 years, the Annual Charles River Cleanup has been a day to celebrate Earth Day and engage individuals in community service. Helping to connect individuals with the environment, the Cleanup increases understanding of environmental stewardship and furthers the CRWA’s mission to preserve, protect, and enhance the Charles River. Uniting over 3,000 volunteers to clean up the entire length of the Charles River, participants in the cleanup volunteers can easily connect their daily habits to the trash they pull out and around the Charles River.”

MIchigan Clean Up Our River Banks (CUORB): “Little over a year old but 1600+ tires, too many bags of litter to count and too much scrap metal to move has been taken out or located to be for next spring. Bring on 2018!”

Pearl Riverkeeper: “In three short months, volunteers from all walks of life and demographics helped us plan a river cleanup across 15 Mississippi counties and two Louisiana parishes. Our inaugural event was a giant success with over 1,000 volunteers cleaning 34,000 pounds of trash out of the Pearl River watershed. It was an inspirational event that highlighted just how much the Pearl River means to us all.”

Eastern Pennsylvania Coalition for Abandoned Mine Reclamation (EPCAMR): “EPCAMR works with dozens of coalfield communities throughout…PA that have been previously impacted by abandoned mines and provides financial and technical assistance to them yearly to conduct cleanups along stream corridors and on landscapes that have been littered with illegal dumping. Centralia holds a special place in the hearts of the EPCAMR Staff. Many former residents come from out of state to support the cleanup efforts every year and this was our 4th.”

Teddy Bear Project: “Teddy Bear Project began in Rockaway Park (Queens), New York…to engage volunteer[s] in partnership with St. Francis De Sales Quilting Bee…Teddy Bear Project lost everything in Hurricane Sandy but relocated to [the] Bronx River in West Farms Square, Bronx. [The group’s] mission “All Things Warm & Fuzzy” found new purpose, however. The new goals include the power of volunteers, but the new community has a river in which [a] serious call for action is necessary.”

CT River Conservancy (CRC): “2017 was a celebratory year for CRC, marking both our 65th anniversary as the voice for the CT River and our 21st year organizing the Source to Sea Cleanup. The Cleanup is a unique 4-state effort with over 2,500 volunteers in 170+ local groups and fits into our broader work of caring for and protecting our rivers, keeping them clean & beautiful for the wildlife and recreationists that depend on them, and educating and engaging people to get more involved in their rivers. CRC uses trash data collected during the cleanup to support legislation and other efforts to keep trash out of our rivers. That includes expanding bottle bills to put a deposit on more plastic bottles, making curbside recycling easier and more accessible, and requiring tire manufacturers to run free tire disposal programs to discourage illegal tire dumping.”

Friends of the White River: “In 2017, we held our 29th annual Spring Downtown Cleanup. This is our largest event, totally land-based, through downtown Indianapolis. Look for a special big event in 2018, celebrating our 30th year!”

It goes without saying that National River Cleanup® wouldn’t exist without our 2017 Cleanup Champions and hundreds of others who register with us each year. Because of these organizers and their deeply-valued volunteers, we are able to work toward a future of trash-free rivers, creeks, and streams.

The Cape Fear River in North Carolina has been making headlines in 2017 due to the unregulated release of a potentially toxic chemical – GenX – from the Chemours manufacturing plant in Fayetteville, NC. There are tens of thousands of unregulated chemicals in the United States that are only minimally managed before being released into our rivers and streams. This creates issues for drinking water systems that are using that water to provide clean water supplies for communities as well as for ground water supplies as those systems are not designed to filter out these unregulated chemicals.

PBS’ News Hour program did an indepth story of the problem on the Cape Fear.

The laws regulating chemicals in the U.S. and in the states have not been updated to protect communities from the potential threats of the constantly changing mix of chemicals that are used and discharged. A new system needs to be developed to keep untested chemicals from entering our clean water supplies.

Amidst the largest dam building era in the United States, Congress realized urgency around preserving certain rivers with outstanding natural, cultural, and recreational values in a free-flowing condition for the enjoyment of present and future generations. In 1968, President Lyndon Johnson signed The Wild and Scenic Rivers Act into law, giving rivers a special designation to protect the remarkable values that free-flowing rivers have across the country. The Act is notable for safeguarding the special character of these rivers, while recognizing the potential for their appropriate use and development. It encourages river management crossing political boundaries and promoting public participation to develop goals for river protection.

There are about 3 million river miles across the United States. Since being signed into law, The Wild and Scenic Rivers Act has protected nearly 13,000 miles of river. Today, less than one percent of America’s rivers are wild and free. Special reaches like the Middle Fork of the Salmon, Rogue, Chattooga, Tuolumne, and New Rivers are all protected under this designation, but many rivers remain at risk.

In this week’s episode of We Are Rivers, we discuss the history and background of the Act while describing the ever-growing need to do more to protect wild rivers and streams across the country. Join us to learn more about the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act and discover how you can get more involved with protecting rivers and streams across the country.

You can also find us in iTunes and Stitcher!

In my foreword to Tim Palmer’s wonderful new book, Wild and Scenic Rivers: An American Legacy (Oregon State University Press 2017), I wrote about one of the battles that inspired me to dedicate my career to environmental conservation. This was the fight in the early 1970s in my home state of Kentucky to protect the Red River and its spectacular gorge from an unnecessary and wasteful dam. In an era when any free-flowing river was viewed by politicians and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers as an opportunity for dam building and pork barrel largesse, the Red River was ripe fruit waiting to be picked.

Thanks to determined opposition from local farmers and residents who did not want their pastures and homes submerged beneath a reservoir; the support of paddlers (including some of the founders of American Rivers), hikers, and climbers who valued the Red River Gorge and its recreational opportunities; and the timely appearance of U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, who hiked the Gorge to highlight its rugged beauty, the dam proposal was defeated. In 1993, the Red River was permanently protected as Kentucky’s only federal Wild and Scenic River.

This year, 2018, marks the 50th anniversary of the landmark Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. Wild and Scenic Rivers are special places: rivers that communities have chosen to protect because of their outstanding cultural resources, fish and wildlife, clean water, recreation or scenic values. The designation by Congress prohibits construction of a dam, or other development that would harm the river’s unique character.

We have a lot to celebrate in this anniversary year: Today, thanks to the efforts of American Rivers and our partners and supporters across the country, the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System safeguards more than 12,700 miles along parts of 208 rivers and three million acres of riverside land in 40 states and the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico.

We also have a lot more work to do. Many of our most treasured rivers remain unprotected from new dams, mining and other harmful development – special places that could be lost to future generations. That is why, in this 50th anniversary year of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, American Rivers and our partners have launched the 5,000 Miles of Wild® campaign. Our goal is to protect 5,000 new miles of Wild and Scenic Rivers and one million acres of riverside lands over the next five years. At a time when the Trump Administration and many in Congress are dismantling safeguards for our clean water and public lands, we must speak up louder than ever and demand protections for the rivers we love.

For me, one of those places is Washington’s Olympic Peninsula. Last year, I had the privilege of going steelhead fishing on the Queets, Hoh and Quinault rivers, which the 5,000 Miles of Wild campaign is working to protect. It was a classic Northwest steelhead experience: February, raining and 45 degrees. I learned why steelhead are called the Fish of a Thousand Casts — I must have cast 999 times because I had but one grab of the colorful streamers I was casting with a two-handed Spey rod, with no fish hooked.

Despite this, I had a fantastic time — it was a true “bucket list” trip. Even in the rain, the rivers were a beautiful gray-green as they flowed off of glaciers and through the protected forests in Olympic National Park. By contrast, the nearby Humptulips River was a murky brown, full of sediment runoff from its heavily logged watershed. This provided a vivid illustration of the value of permanently protecting rivers and their watersheds.

As we pursue our goal of protecting 5,000 new miles of Wild and Scenic Rivers nationwide, the memories from this trip and from the fight to save Red River Gorge remind me what’s at stake and inspire me for the work to come.

Today, Kentucky’s Red River, and the other 207 Wild and Scenic Rivers nationwide, flow freely thanks to the hard work of many individuals who have come before us. Now it’s our turn. I hope you will join me in working to protect the wild rivers of Washington’s Olympic Peninsula, Montana’s headwater streams in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem and Crown of the Continent, Colorado’s Deep Creek, pristine mountain streams in the forests of North Carolina and many others across the country as Wild and Scenic.

Sign our petition at www.5000miles.org and share your river story. Now is our moment to launch the next 50 years of river protection in our country. Together, we will make a lasting difference for the rivers that connect us all.

[su_button url=”https://www.5000miles.org/petition/” background=”#ef8c2d” size=”5″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

Click here to launch the visual tour of California’s floodplains |

2017 has been a landmark year for floodplains in California’s Central Valley.

The 2017 Central Valley Flood Protection Plan Update now embraces a dramatically different approach called “multi-benefit” flood management. This approach recognizes that by reconnecting floodplains and expanding floodways and flood bypasses, we can reduce flood risk to people and property while providing multiple benefits including habitat for fish and wildlife, improved recreational opportunities, groundwater recharge, and improved water quality, to name a few. American Rivers has been championing this approach for the last decade.

In addition, great strides were made in advancing specific multi-benefit projects that will help achieve ecological outcomes outlined in the new flood plan. American Rivers is leading and assisting in planning efforts on several projects that are identified in the new Plan as priority projects. Projects that actually broke ground this year include West Sacramento’s Southport levee setback project, the Hamilton City levee setback project, and the Yolo Bypass Adult Fish Passage Improvement project. You can see where these are happening and learn more about them on our revamped multi-benefit flood management website.

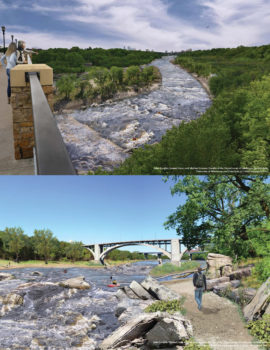

Since the Upper St Anthony Falls Lock was ordered closed in 2015, the Minneapolis-St Paul community has been considering the future of the Mississippi River in the Gorge – the stretch of river between the falls and its confluence with the Minnesota River about 10 miles downstream. The Mississippi River Gorge was once a long stretch of whitewater, but over the last century it has been dammed and pooled for hydropower and navigation. Today, the Army Corps of Engineers owns the two dams in the Gorge. With relatively little barge traffic and high maintenance costs, the Army Corps is evaluating the fate of the infrastructure. Without navigation and the associated investments from the Army Corps, the river through the Gorge will change.

Dam 1 by US Army Corps of Engineers (top) and Lower St Anthony Falls Dam by Olivia Dorothy (bottom).

In response the Army Corps’ evaluation, American Rivers hosted a public meeting in summer 2017 with the neighborhood Longfellow Community Council about the future of the Mississippi River in the Twin Cities. We were interested in hearing what the community thought about removing the dams to restore the Gorge.

The meeting was very well attended, with more than 100 people filling the pews at St. Peder’s Church in Minneapolis. To start the meeting, experts from the National Park Service, Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, and Army Corps of Engineers talked about the natural history of the Mississippi Gorge and the Corps’ process for determining the fate of the infrastructure. American Rivers’ Brian Graber and Olivia Dorothy talked about the multiple benefits of dam removal and how removing the dams could restore the Mississippi River in the Twin Cities.

Mississippi Gorge restoration renderings from Lake Street (top) and Franklin Street (bottom). Click to enlarge.

Following the presentations, critics of the proposal were vocal. Rowing club members lamented the loss of calm pools should the dams be removed. Others were concerned about the loss of hydropower, a renewable energy source for the community, and the lack of coordination thus far with the Native American community. However, after all the written comments were reviewed, they showed that about twice as many people expressed support for river restoration as opposed it. While the critics have been vocal in expressing their significant concerns about restoring the river, it seems the majority of participants actually support the restoration concept.

And the comments and conversations generated several questions that American Rivers and partners plan to explore, including:

- Identifying other locations for competitive rowing activities.

- Replacing lost hydropower with another renewable energy source.

- Clarifying the environmental benefits of dam removal in the gorge.

- Developing plans to expand/improve recreational access.

- Exploring the needs of minority and low-income people in planning.

- Identifying any infrastructure that might be vulnerable to changing river discharge.

Moving forward, American Rivers will work with partners to explore these six areas of interest to better understand and articulate the restoration option for the Mississippi River in Minneapolis-St. Paul. In the meanwhile, the Army Corps has stalled their study of whether to retire the locks and dams as they await funding from the federal budget. We are hoping that study resumes in the next year.

To read the full report from the meeting and summer survey, visit https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1yvh37LdfRtleKcdxD7zA0itR3V7ayyYV?usp=sharing

Guest post by Nikhil Mendiratta, a junior at Georgetown University within the McDonough School of Business.

This semester, I had the opportunity to work with American Rivers as a Project Manager with Hilltop Consultants at Georgetown University. Hilltop Consultants is an entirely student-run organization that works with nonprofits in the United States and abroad to provide strategic and meaningful solutions for various issues. We typically select five-six client groups for a strategy consulting engagement each semester. I have been involved in the organization since my freshman year, and this was my first opportunity leading a team of consultants to complete a client project.

Through a semester-long consulting process, Hilltop teams take a deep dive addressing issues, overcoming a barrier, or tackling a challenge presented by our clients. In this case, the project presented by American Rivers was quantitative and financial in nature, which fit well with my background. I study finance and accounting, and worked at Citigroup this past summer, so I was excited to be working on this project. Of course, I would not have been able to complete this project without an incredible team comprised of a senior consultant and three other members, who hit the ground running from week one in early-September.

The project consisted of three key areas. Most importantly, we researched how American Rivers could build a new model to forecast corporate and foundation revenue. Additionally, we examined how American Rivers compared to its peers in terms of the breakdown of its revenue sources. Finally, we recommended key performance indicators (KPIs) that the corporate and foundation fundraising team could use for internal evaluation and decision-making. Our research process involved both academic research and real-world case studies, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of each situation.

Ultimately, we compiled recommendations about how American Rivers can implement our findings going forward. We included step-by-step guides about the implementation of five different forecasting models, in addition to a discussion of forecasting methodology and modeling best practices. Furthermore, we updated a previously completed analysis of the revenue breakdowns of other conservation organizations to include data from similarly sized organizations without a conservation focus. Finally, we recommended a new methodology for key performance indicators and specific KPIs that American Rivers can implement. Our project culminated in a presentation of our findings and recommendations to the staff on December 11th, 2017.

Overall, our team had a very positive experience working with American Rivers throughout the fall semester. The biggest takeaway for me was understanding how nonprofit organizations operate. This project is revenue-based, so I have learned about factors that drive both revenues and expenses, as well as how financials generally work in nonprofits. It’s very different from my previous experiences working with large corporations and analyzing large market cap companies.

A highlight was when we were able to participate in a National River Cleanup event in October. The team went to Teddy Roosevelt Island and spent a few hours cleaning up the Potomac River, just a short walk from our campus. It was an eye-opening experience about river cleanliness, and helped us become even more committed to advancing the mission of American Rivers.