The City of Raleigh is emerging as a leader in the use of green stormwater infrastructure (GSI). In the fall of 2017 the City completed a multi-year process to update its policies to encourage the use of GSI throughout the City. This was the culmination of the City’s Green Stormwater Infrastructure strategic plan.

The work grew out of a call to action by the City Council in the early 2000s committing to improve the health of local streams and the Neuse River but promoting Low Impact Development (LID). That commitment took nearly a decade to be converted to action by the City. In 2013, Raleigh Stormwater began the process of developing in earnest the GSI strategic plan. The plan development was facilitated by Tetra Tech. The first phase was internal to the City working with various City departments to educate staff and learn about potential barriers within the City structure to successfully implementing GSI across the City. This is a critical step in truly integrating GSI into the basic mechanisms of a city – city staff at all levels and all departments need to see how using GSI can aid their work rather than be a burden.

In 2015, the public phase of the plan launched with the creation of two work groups- the Code Review Work Group and the Implementation Work Group. These work groups included interested citizens, city staff, developers, engineers, and environmental groups. American Rivers was engaged on both over the next year and a half of work.

Raleigh began implementing its green stormwater infrastructure strategic plan in September 2017. The new plan includes revision of the City’s Unified Development Ordinance (UDO) to remove barriers to the use of green stormwater infrastructure and the development of an incentive program for private developers to use GSI in new and redevelopment. The incentive program is particularly noteworthy since it is not a cash incentive; in the process of the development of the incentives we heard from developers that the preference would be for a streamlined permitting system that offered timeliness and certainty. The City of Raleigh in response is creating a ‘green team’ that works with developers to integrated GSI into their plans and in return shepherds the project through the City system. The City also has its on-going cost share program to offset the costs associated with retrofitting existing private development with GSI.

This plan and investment in retrofits sets Raleigh apart as a leader in the use of GSI and a model for other communities across the country.

You can’t wall off a river and expect the river, its wildlife, or its people, to survive. That’s why we put the Lower Rio Grande on the list of America’s Most Endangered Rivers® of 2018.

“The Rio Grande is so much more than a border,” says Chris Williams, Senior Vice President for Conservation at American Rivers.

“It is a life-giving source of water, a cultural crossroads, a pillar for local economies, a scenic treasure, and a unique freshwater ecosystem. Construction of a border wall, unhindered by any meaningful environmental review, disrupts and damages that ecosystem, impacting everything that depends on it.”

President Trump has proposed the construction of hundreds of miles of new border walls along the Rio Grande, and Congress has agreed to fund this first phase of construction. The first 30 miles of this new phase of wall building have already been mapped, and preparations are under way for construction in the Lower Rio Grande floodplain.

River guide Austin Alvarado. “Before the Rio Grande is a border, it’s a river,” he says. | Photo: Ben Masters

Much of this new construction will be “levee-walls”— essentially a steel fence on top of a large levee— that will cut the Rio Grande off from its floodplain, potentially exacerbating flooding and erosion and blocking access to this life-giving resource for people and wildlife.

In the coming years, President Trump will likely push Congress to fund additional border wall construction. Trump has called the current $1.57 billion appropriation a “down payment” on an eventual $25 billion over ten years.

We’re calling on Congress to refuse to appropriate another penny for this damaging and wasteful project.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/4986/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”4″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

New Rio Grande border walls will have multiple impacts: habitat corridors will be severed and endangered species will be pushed closer to extinction; natural inflows into the river will be disrupted; wetlands will be destroyed; floodwaters will be deflected, potentially moving the river channel; flooding in communities along the river will be worsened; and access to the river for residents and landowners will be disrupted.

In addition to the Lower Rio Grande, America’s Most Endangered Rivers of 2018 is a snapshot of some of our nation’s most beloved and iconic rivers in the crosshairs. The list includes:

- The recreation paradise of the Boundary Waters

- The rivers of Alaska’s world-famous Bristol Bay

- The Mississippi River in the heart of Minneapolis

In our many years of issuing the America’s Most Endangered Rivers report, we’ve seldom seen a collection of threats this severe, or an administration so bent on undermining and reversing protections for clean water, rivers and public health.

Your support is vital as we fight for America’s Most Endangered Rivers of 2018, and rivers nationwide.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/5027/donate/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”4″ center=”yes”]Donate today »[/su_button]

Senator John McCain called it “one of the worst projects ever conceived by Congress.”

Former Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt called it “godawful, cockamamie.”

They were talking about the Yazoo Pumps, an Army Corps boondoggle that would devastate Mississippi’s Big Sunflower River and cost taxpayers hundreds of millions of dollars.

Thanks to President Trump and his allies in Congress, this terrible project is back and it poses such a threat that we placed the Big Sunflower River at the top of the list of America’s Most Endangered Rivers® of 2018.

The Big Sunflower River is a special place…

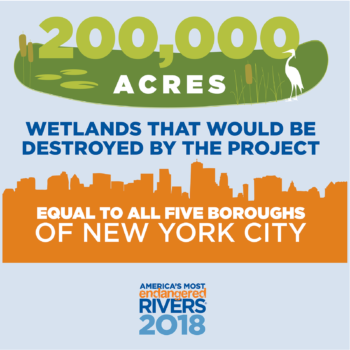

The Yazoo Pumps project would cause a mind-boggling amount of damage…

The Yazoo Pumps project would cost taxpayers at least $300 million. That’s a lot of money…

It’s time to stop this terrible project once and for all.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/4999/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”4″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

In addition to the Big Sunflower River, America’s Most Endangered Rivers of 2018 is a snapshot of some of our nation’s most beloved and iconic rivers in the crosshairs. The list includes:

- The recreation paradise of the Boundary Waters

- The Lower Rio Grande along the border with Mexico

- The rivers of Alaska’s world-famous Bristol Bay

- The Mississippi River in the heart of Minneapolis

In our many years of issuing the America’s Most Endangered Rivers report, we’ve seldom seen a collection of threats this severe, or an administration so bent on undermining and reversing protections for clean water, rivers and public health.

Your support is vital as we fight for America’s Most Endangered Rivers of 2018, and rivers nationwide.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/5027/donate/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”4″ center=”yes”]Donate today »[/su_button]

Thank you for standing with us.

In this episode of We Are Rivers, we discuss the collaborative efforts Arizona and other Lower Basin states and water users are taking to address challenges facing the Colorado River and solutions, including the Drought Contingency Plan.

This blog was co-authored by Jeffrey Odefey & Kathryn Sorensen, Director of Phoenix Water Services

Arizona is a renowned leader in water management thanks to more than a century of careful planning and effective leadership. But, with drought and declining water levels in the state’s key water supplies, Arizona must do more.

Nearly half of Arizona’s water is provided by the Colorado River via the Central Arizona Project (CAP) canal. However, the Colorado River is over-allocated. Over the past decade, the Colorado River has been the subject of a series of high-profile planning efforts and negotiations, including the recently proposed Drought Contingency Plan. These efforts reflect the widespread recognition of significant legal over-allocation and physical overuse of water in the Colorado River Basin, as well as a more accurate understanding of historic hydrology in the Colorado River Basin and the likely near-term impacts of climate change.

Due to both drought and the basic problem of over-allocation of the river, Lake Mead levels have dropped quickly, leaving Arizona at risk of a shortage declaration that will diminish the amount of Colorado River water available to Central Arizona.

System conservation is an innovative and extremely promising approach to reducing risk and building resiliency and certainty into Colorado River Basin operations. Willing funders compensate water users who are willing to voluntarily reduce their water use. Voluntary system conservation allows Colorado River users to collaborate on ways to use less water in the lower basin so that it can be stored in Lake Mead to benefit the system as a whole. This storage benefits people and communities because a model that sustains Lake Mead’s water levels will allow people and communities to predict and understand the long-term management of the Colorado River.

The Colorado Basin states have inherited this problem, and it is our inherent duty to work together to fix it. Public health, economic development, and quality of life here in Arizona are contingent upon a reliable and safe water supply. We must be committed to building resiliency and implementing innovative water management strategies to ensure dependable water supplies for generations to come.

Tune in to “Episode 10: Securing Arizona’s Water Supply is a Team Effort,” to hear how Arizona and other Lower Basin states are working together to reduce demand of the Colorado River through the Drought Contingency Plan.

You can learn more about this collaborative project at 4states1source.org.

The William Penn Foundation recently announced more than $40 million in new funding for the Delaware River Watershed Initiative (DRWI), which is among the country’s largest non-regulatory conservation efforts to protect and restore clean water. The DRWI is a first-of-its-kind collaboration, where American Rivers is one of 65 organizations working together to protect and restore the Delaware River and its tributaries, which provide drinking water for 15 million people in Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey, and Delaware.

The DRWI is tackling widespread pollution problems that threaten clean drinking water and the health of rivers and streams. This includes erosion and runoff from deforested acres in headwaters, polluted runoff from agricultural fields, flooding and polluted stormwater from cities and suburbs, and a depleted aquifer in southern New Jersey.

In 2014, the DRWI launched a new approach, joining local and regional groups to accelerate conservation efforts. Today, the DRWI stands out as a basin-scale program driven by non-profits like American Rivers, guided by science. In just over three years, DRWI partners have;

- Protected 19,604 acres,

- Restored 8,331 acres, and

- Monitored and sampled water quality at more than 500 sites across four states.

With learnings gleaned from the past four years, this additional $40 million dollar, three-year investment builds on DRWI’s initial successes to protect and restore an estimated 43,484 additional acres, and it allows DRWI to continue its scientific approach to securing clean, abundant water in the basin.

American Rivers has been very involved in the campaigns to protect and restore the Delaware River system that supplies water to 15 million people, many of whom live in Pennsylvania. As a member of the DRWI, we have led the push to advance green stormwater infrastructure and assess scientific and economic findings to create a plan to improve upstream/downstream connected buffer protections within the Basin in Pennsylvania. American Rivers has also been a part of the national Clean Water for All Coalition and supported the comprehensive development and successful launch of the campaign in the mid-Atlantic.

We are excited to see how this will continue to flourish to the benefit of all Pennsylvania residents, and all residents in the Delaware River Watershed.

This guest blog by David Wick is a part of our 2017 America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series on the South Fork Skykomish River.

The past few weeks, we’ve been detailing the issues with the Snohomish County PUD (SnoPUD) proposal to build a new powerhouse at the base of Sunset Falls on the South Fork Skykomish River and reroute water from a 1.1 mile reach of the river between Canyon and Sunset Falls. This proposal is a threat to outstanding fish, wildlife, recreation, and scenic values of the Skykomish and in this post we’re going to jump in to some of the specifics about the threats and the issues this proposal would pose to the imperiled runs of salmon and steelhead.

Since 1958, the Washington State Dept. of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) has operated a trap and haul facility at this site to transport wild fish above Sunset, Canyon, and Eagle Falls to approximately 90 miles of cold water spawning habitat. Ecosystem Diagnostic and Treatment (EDT) modeling for Chinook salmon in 2004 and 2005 suggested that the South Fork Skykomish River above Sunset Falls is the most productive area for Chinook in the Skykomish system. According to filings from the Tulalip Tribe, Chinook production above Sunset Falls represents upwards of 30% of the natural origin spawners in the Skykomish population and 20% of the Chinook within the entire Snohomish basin.

The purpose of the trap and haul facility is to sort the returning mature fish and to transport wild Chinook, coho, sockeye, shum, and pink salmon, including bull trout and steelhead, above the falls. Hatchery salmon are returned to the hatchery to be sacrificed for roe and milt, and hatchery steelhead are dispatched and donated. Needed trap and haul improvements include a new truck and better sorting equipment. SnoPUD is offering approximately $3 million for these one-time, off-license upgrades as an enticement for locating their powerhouse adjacent to the trap and haul facility. While improved handling may lessen the impacts to overall fertility, that better handling of up-migrating fish does not cause them to grow larger, survive longer, or to become more abundant.

Part of increasing fish abundance requires the successful down-migration of juvenile salmon and steelhead over the falls and for that, ample flows are needed. This is the proposed project’s fatal flaw.

According to some fisheries experts familiar with the basin, the project will impair downstream fish passage as well as degrade and reduce fish habitat necessary for spawning salmon and other native fishes in the South Fork Skykomish River system, by reducing median monthly flows 63 – 90%.

To make the project economically viable, SnoPUD needs to drastically reduce the river flow over the falls by diverting most of the flow through its hydropower facility. According to plans filed with FERC, juvenile fish will be screened and deposited in the de-watered bypass reach. Juveniles remaining in the river will pass over Canyon and Sunset falls with inadequate water to cushion their landing on the rocks below.

According to statements filed with FERC, SnoPUD’s proposed project is neither economically viable nor in the interest of its ratepayers. The project could not operate for three months per year due to low summer flows and relies on securing a minimum instream flow of 250 cfs, which is wholly insufficient for the habitat needs within the bypass reach. The proposed instream flow conflicts with state minimum instream flow rules, and the entire project area is further protected from hydropower development under the Northwest Power Act.

In its draft license application Exhibit E, Section E.1.4.2. Endangered Species Act (page E-15), SnoPUD rightly concludes “that findings of ‘may affect, likely to adversely affect’ are appropriate for Chinook salmon in the Puget Sound Evolutionarily Significant Unit (ESU), and winter-run steelhead and bull trout in the Puget Sound Distinct Population Segments (DPS). While the District’s proposed construction best management practices are intended to protect aquatic resources, the risk of incidental adverse effects on individual fish (i.e., incidental take under the ESA) cannot be entirely eliminated. The Project may also adversely affect designated or proposed critical habitat for these species.”

Chinook and coho salmon populations are at or near historic lows, and adding a new source of mortality is not appropriate. The project threatens to do irreversible damage to populations at risk as well as to critical habitat required by Chinook salmon as established by NOAA (50 CFR Part 226, September 5, 2005). Considered cumulatively with all other sources of mortality or population pressure, the project has the potential to move threatened populations to endangered status.

In April 2016, the Tulalip and Snoqualmie Tribes formally requested that the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission deny PUD’s application based on anticipated harm to juvenile salmon and steelhead.

Currently, 15 different salmon and steelhead stocks in Washington State are listed under the Federal Endangered Species Act and the productivity of the ESA-listed natural origin Skykomish Chinook salmon population has substantially declined over the past 15 years to well below the replacement level, meaning the population is currently in steep decline.

Southern resident orca whales are also at a 30-year population low. In 2015 the federal government declared that our orca whales are among eight species most likely to go extinct without dramatic action. In just the last two years, seven whales have died. Lack of Chinook salmon has been strongly implicated as the main cause of decline. Despite spending millions on fish studies, SnoPUD has not examined or commented on the potential effects of the proposed project on Orca Whales.

But there is still hope. Joseph Bogaard, executive director of the Save our Wild Salmon Coalition (a coalition of more than 40 organizations) says that, “Salmon are a very prolific species. If you give them a healthy river they will do the rest. The most important action we can take to help salmon and steelhead survive and thrive is to restore healthy habitat and access to healthy habitat.”

Let’s not repeat the same mistakes made in Europe and New England where the salmon decline was not only dramatic, but permanent.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/1233/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”4″ center=”yes”]Take Action »[/su_button]

In a year of political upheaval and attacks on environmental safeguards, American Rivers continues to claim some significant victories – thanks to you, our supporters.

President Trump signed the omnibus spending bill on Friday, and it’s an important victory for rivers and clean water.

Here are some of the ways our rivers, clean water supplies, and communities won in the spending bill:

- $8.821 billion for the Environmental Protection Agency ($763 million more than the 2017 enacted level) that includes vital funding to prevent water pollution and safeguard drinking water.

- $209 million (up from $100 million) for FEMA to reduce flood risk for communities through better planning, and rebuilding homes and businesses away from floodplains.

- $104 million (up from $75 million) for the WaterSMART program’s water efficiency efforts.

Also important is what’s not in the bill: we were able to fight back several harmful anti-environmental riders, including one that would have prevented public scrutiny and judicial review of the Trump administration’s efforts to repeal the Clean Water Rule.

While we celebrate this good news, we are continuing to defend our rivers from a series of attacks from Congress and the Trump administration. We’ll be sounding the alarm about urgent threats to ten rivers on April 10, when we announce America’s Most Endangered Rivers® of 2018.

To all of you who help make our victories possible, and who stick with us through all of the battles – thank you.

In December 2017, American Rivers helped remove three 100-year-old earthen and concrete dams from Hamant Brook in Sturbridge, Mass., restoring habitat for native brook trout, wood turtles, and mussels. We caught up with the project’s director, Amy Singler, to learn what inspired her about Hamant Brook and where she goes from here.

Why remove these dams?

There is an old joke: What does a fish say when it bumps its head? “Dam!” When you build a dam, fish can’t move up and down their natural habitat. By removing the dam, we restore access to habitat, as well as the ecological function of the river. Plus, a lot of old dams are safety hazards, and can be liabilities for their owners and the community.

Most of the dams I work to remove are smaller industrial-era dams that are up to 300 years old. In a lot of cases, the dam has outlived its usefulness and its costs outweigh its benefits.

Removing dams sounds pretty easy. Is it?

Removing a dam can be incredibly complex, and that’s why it’s important to have a group like American Rivers help dam owners and community leaders navigate the many steps. We work with engineers to figure out what it will take to remove the structure, and we secure funding and necessary local, state, and federal permits. It took six years of work on Hamant Brook before the big yellow machines came to pull the dams out. The actual removal and restoration of the riverbed took about three months.

How is Hamant Brook unique?

There is a trail network along the river that people in the community use daily. What is exciting is that as people walk it every day, they will see the native fish coming back in. They will notice the change in the wildlife. They’ll see the plants grow. They get to see the evolution of the river as it comes back to life.

What inspires you?

It’s pretty exciting to think that we’re bringing a river, which hasn’t been a river for a century, back to what it wants to be. When we finally removed the last of the dams on Hamant Brook, the sun was down, and the equipment was gone. I stood there in the dark and listened to the river running. Just four hours earlier you couldn’t have heard anything. I get choked up thinking about it.

How do we strike a balance?

I get my drinking water from a series of reservoirs created by dams, so I understand that some dams are important. But there are so many deadbeat dams around the country that no longer serve a purpose. They’re choking our rivers. We need to be thoughtful about which dams make sense, and which ones need to come down.

Anything you want American Rivers supporters to know?

Having your consistent, ongoing support makes a fundamental difference. That’s the reason we aren’t working on a dozen dam-removal projects—we’re working on dozens all across the country. We have in-house expertise and we’re training a larger network of people to move this forward. We’re pushing forward a movement.

What’s next?

We’re going on a dam hunt in northern New Hampshire and Vermont—talking with community members, and identifying dams to remove and rivers to restore. Freeing rivers never gets old.

Watch a timelapse video of a dam being removed from Hamant Brook below:

This guest blog by Irene Nash is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series on the South Fork Skykomish River.

Towering snow-capped mountains. Jagged granite peaks outlined against a brilliant sky. A powerful river carves its way past massive boulders as eagles hunt overhead, occasionally joining talons and spiraling downward together in what looks like a crazy, out-of-control game before separating and flapping regally away just before they reach the treetops.

It sounds like some wonderland tucked away in the Swiss Alps or a remote nature preserve, but amazingly this wild place exists in the Skykomish Valley – less than an hour from Seattle, one of America’s fastest-growing major cities.

Flowing through the Skykomish Valley, around 45 miles northeast of Seattle along National Scenic Byway Route 2, is the beautiful Skykomish River, a year-round playground for whitewater paddlers. With two roadside sections ranging from Class II to III+ and a powerful rite of passage Class IV rapid (Boulder Drop), “the Sky” is a kayaking classic and one of Washington’s most beloved rivers.

It’s sometimes difficult to describe the beauty of the Skykomish Valley. Last year, it was made apparent to me after returning from a kayak trip to some remote and beautiful areas of Ecuador. After returning home, I surprised myself by telling my husband, “You know, our river valley is actually prettier!” We had the same reaction after paddling the Colorado River of the Grand Canyon. Yes, the scenery was fantastic, but there’s never a time that we return from any kind of trip without feeling a sense of disbelief that something as gorgeous as the Skykomish Valley is our backyard.

However, it’s easy for people to take for granted and I think that’s happening now, especially with the looming threat of the proposed hydropower project at Sunset Falls on the South Fork of the Skykomish River. My husband, who is from New Zealand, always points out that, “If this were New Zealand and the Skykomish Valley were within one hour of Auckland, the entire area would be thriving on recreational tourism and any idea of using the Skykomish River for hydropower would be ludicrous.”

With a long history of extractive industries forming the basis for local economies, however, it takes a forward-thinking mind shift on the part of policy-makers to entertain the idea that the future of this area may no longer lie in resource extraction, including the dubious and extremely optimistically framed economics of hydropower at Sunset Falls.

The economies of the towns along Highway 2 aren’t going to be supported by just whitewater kayaking, but there’s huge potential for them to tap into the resources of the thousands of recreational visitors who stream through the Skykomish Valley in growing numbers each week to hike, camp, ski, and fish. Just ask anyone who lives in the valley about traffic on Highway 2 and they’ll tell you it has gotten drastically heavier in just the last five years.

Hikers: Nick Baughman, Dave Moroles, Kevin Hoffman. The Skykomish Valley seen from the Index Wall. | Photo by Nick Baughman

Many of these visitors come for the wilderness and outdoor recreation opportunities, which brings up the question: Isn’t it incredibly short-sighted to potentially scuttle the future of this area by planning mis-guided industrial projects that demolish wild characteristics and remove options for outdoor recreation?

I can easily picture the kids of today looking back in 20 years and asking our current policy-makers: “What were you thinking?”

For now, the Skykomish River flows freely and the tens of thousands of hikers who use the nearby Lake Serene Trail each year don’t yet have to hear explosions from diversion tunnels that proponents of the Sunset Falls hydropower project would like to see blasted into existence. Let’s hope common sense and a smart vision for the future prevail for this wonderland that is the Skykomish River Valley.

Help stop this dam from ruining the wild Sky River. Some places are too special to ruin with development and diversions.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/1233/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”4″ center=”yes”]Take Action »[/su_button]

Guest blogger Irene Nash is a whitewater kayaker who lives in the Skykomish Valley with her husband and two dogs.

Weather in Colorado can be a fickle beast. Last year, despite the winter starting on a dry note, Colorado ended with a significant amount of precipitation across the state, particularly across the Western Slope. The snow was so deep in some communities that ski areas closed due do too much snow!!

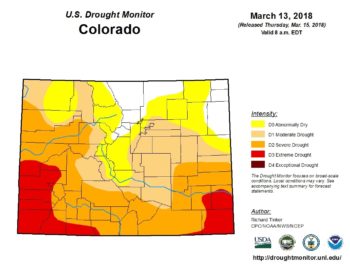

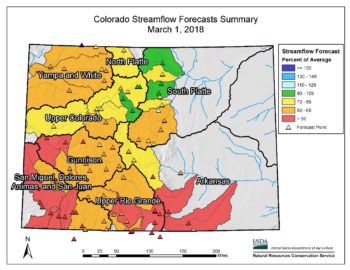

But this year, it’s a different story. On my drive into the high country earlier this week, it was impossible not to notice a missing aspect of the landscape: snow. Colorado, like other states across the southwest and high plains is dry. Very, very dry. Warm temperatures with scant precipitation has been the norm for most of the winter, and despite a bit wetter February, it wasn’t enough to lift the state’s precipitation even to an average level – and the southwestern corner is still well below 75 percent of normal snowpack. Unfortunately, forecasts predict continued dry conditions into summer – we can no longer hope for a wet spring to save the day. As of March 14th, Colorado would need nearly 360 percent of normal snowfall to bring snowpack up to optimal levels.

So what does this mean for rivers?

Without a significant amount of moisture, and soon, summer flows across the state are destined to be much lower than average. The southwest and southeast parts of the state are experiencing the greatest threat, with snowpack in surrounding mountains being dismally low. The Gunnison, San Miguel, and Dolores River Basins are projected to produce 45 – 51 percent of average stream volume, and the Animas in early March experienced some of the lowest flows through Durango on record. However, while current reservoir levels across the state are at or above average (current storage total is around 116 percent of average) we can’t gamble our future on a great snowpack next year to replenish this year’s consumption. The trends are for less snow more often, and changes must be made to safeguard our rivers.

Colorado depends on our rivers for agriculture, recreation, municipal needs, and drinking water supplies. And we, as Coloradans, know that we cannot rely on weather patterns to get us out of a problem. The climate is changing, and overall we are experiencing more consistently dry years, with wet years becoming few and far between. We need to implement common sense solutions to cope with a future where there is regularly less water and drier conditions across Colorado.

While the snowpack situation isn’t looking great for us this year, water managers across Colorado were forward thinking in the creation of Colorado’s Water Plan. They identified collaborative, smart, and efficient solutions to protect our clean drinking water supply, and healthy rivers have and will continue to be a critical part of how we manage water and rivers here in Colorado. Colorado’s Water Plan identifies the fundamental solutions to preserve our clean, safe, reliable drinking water supply and protect the places we all love.

It’s unlikely we’ll hit the almost 360 percent of precipitation we need in the coming months just to get to average this year, which is why we must continue circling back to conservation and the protection of our rivers. Continued implementation of the Water Plan may alleviate the effects of weather swings in years to come by adding flexibility through identified solutions like increased water conservation, more flexible water management, and better protections for healthy rivers and streams. We have viable, cost-effective and strategic actions to ensure a healthy water future for Colorado, and by embracing these efforts now, and supporting increased funding for the plan into the future, we can make the best bet toward sustaining Colorado’s rivers through these dramatic, and unpredictable, swings in Colorado’s wild weather.

The South Fork of the Skykomish River in Washington’s North Cascades is a treasured watershed for many important values — recreation, scenic, critical fish and wildlife habitat, and even suitable for a Wild and Scenic designation. But unfortunately it is still ground-zero for a proposed hydropower project located at scenic Sunset and Canyon Falls.

The Project

Sunset Falls Hydropower Project Proposed Intake: The site of the proposed intake for the Sunset Falls Hydropower Project on the South Fork Skykomish River above Canyon Falls.

In 2011, the Snohomish County Public Utility District (SnoPUD) began the regulatory process to study the feasibility of the Sunset Falls Hydroelectric Project to be located on the South Fork Skykomish River near the climbing and boating community of Index. The proposed run-of-river hydroelectric facility for the Sunset and Canyon Falls reach would reroute water from a 1.1-mile stretch of the river, in violation of the Washington Department of Ecology’s instream flow rule, sending it through a roughly 2,200-foot underground tunnel to a powerhouse at the base of Sunset Falls, thus reducing Sunset and Canyon Falls to a trickle (the initial proposal called for an inflatable eight-foot high by 55-foot wide weir which would have been placed at the top of Canyon Falls and diverted through a shorter tunnel and powerhouse). Seven years later, SnoPUD is hoping to file a final license application with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) sometime this year.

Why Wild?

Surrounded by wilderness on both sides, the South Fork Skykomish River and its headwaters flow from deep in the Cascades, draining a breathtaking and fairly untouched 835-square-mile watershed. It is the proud centerpiece of communities along its riverbanks, with many residents who fish, paddle, and enjoy the variety of general river recreation opportunities the river offers.

South Fork Skykomish Coho: Fish community at the site of the proposed intake for the Sunset Falls Hydropower Project on the South Fork Skykomish River. Some great habitat for coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) fingerlings that were in abundance.

If you’re an angler, a member of the Tulalip or Snoqualmie tribes, or an orca living in Puget Sound, you probably have an interest in the imperiled runs of native salmon, steelhead, and trout. And with ongoing habitat restoration work being completed throughout the basin, the threats from this proposed project are just too risky and undermine many of these large-scale and significant habitat investments. Additionally, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) has been operating a trap-and-haul facility for these ESA-listed species since 1958 and trucking them above the falls (they are a natural impassable barrier to fish passage) in an effort to open up more habitat to aid recovery efforts. While the current trap-and-haul facility, located at the base of Sunset Falls, helps with upstream fish heading to their spawning grounds, the proposed project would adversely impact the downstream migration of salmon and steelhead smolts in the spring. And although the SnoPUD is dangling a $1.5-million carrot in the form of a trap-and-haul facility upgrade to WDFW, the plan doesn’t adequately address outmigrating smolt issues.

This section of the river is also popular among the whitewater community, with Sunset Falls once a traditional starting point to the classic run known simply as ‘the Sky.’ And because of these outstanding fish, wildlife, recreation, and scenic values, the South Fork Skykomish has been singled out for by a variety of state, regional, and federal agencies for protection. In 1990, it was recommended by the Forest Service as suitable for Wild and Scenic designation. The Northwest Power and Conservation Council identified it as a Protected Area from hydropower development. And it is recognized as the only Puget Sound river in the Washington State Scenic River system.

It Doesn’t Add Up

And while the Skykomish is a scenic jewel in the heart of a breathtaking landscape that is worthy of protection, this proposed project, no matter where it was located, has many flaws. For starters, the economic feasibility of the project doesn’t pencil out. Since 2013, the proposed construction costs have risen almost 30 percent, from a low estimate of $173-million to a high of up to $260-million dollars. The output from the powerhouse would max out at 30 megawatts (MW), or enough energy, according to SnoPUD research, to power up to 10,000 homes, but would be limited and dependent on minimum stream flows. So realistically, the project’s actual capacity given limited seasonal flows would be more around 14 MW.

An independent study from 2013 estimated that the power produced by the completed project would be two to three times more expensive than if SnoPUD were to simply buy the power from the existing grid— an added expense that would likely be passed on to ratepayers. Even SnoPUD’s own data show that the project is highly likely to operate at a loss for the first 30 years.

Is Nature Stepping In?

While these issues and protections might not be enough to halt what some residents call a ‘zombie’ project (five various hydropower projects have been proposed at this site since the early 20th century by various utilities), Mother Nature might be getting in the last word.

Landslide at Sunset Falls: A large landslide is currently active on the south side of the Skykomish River adjacent to Sunset Falls.

Since 2013, the hillside directly south of the bedrock of Sunset Falls has been sliding and on the move ever since. With a constant trickle of water that seems to come from within the hillside, there are many residents who speculate the river is reclaiming an old course and rerouting to a channel that existed during the glacial age. Should the 300-foot-tall hillside give way to the river, it would completely bypass the Sunset and Canyon Falls reach, thus invalidating the entire project.

As some opponents have pointed out, it also flies in the face of one of the seven criteria submitted in the FERC pre-application documents which state that areas of consideration should have “no known geological hazards or unstable areas that would preclude construction.” It’s anyone’s guess if it could happen naturally anytime soon, but if blasting of the nearby bedrock were to proceed as outlined in the proposal, many residents worry about the effects it might have on the unstable slope.

What’s Next?

Presently, the SnoPUD is trying to petition to Department of Ecology to amend the instream flow rule even though Ecology has noted that the flows established under the existing instream flow rule cannot be impaired. Ecology has the legal authority and responsibility to protect and mandate minimum instream flows to protect designated uses (such as aesthetics, recreation, and fishery resources) under Section §401 of the Clean Water Act and changing the instream flow rule for this project would set a bad precedent and bode poorly for the future of the Skykomish and other Washington rivers.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/1233/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”4″ center=”yes”]Take Action »[/su_button]

Every day seems to bring another headline about threats to rivers and clean water. That makes it even more important to celebrate victories and the progress we are making together to protect local waterways, clean drinking water and priceless ecosystems.

“American Rivers and our supporters all over the country are rising to meet the challenge of protecting rivers and clean water despite the headwinds created by an administration hostile to environmental protection,” says Chris Williams, senior vice president for conservation.

With your support, American Rivers is making a difference. We are fighting back hard against rollbacks to clean water protections, and we are making real solutions happen—from removing dams to helping underserved communities advocate for cleaner water to working at the local, state and federal level to put plans in place that safeguard our most precious resource.

Some of these victories for water will last generations. Others are temporary. We must stay vigilant and keep the pressure on. In the meantime, here are a few wins we can all be proud of.

Hoback River, Wyoming

To stop fracking at the headwaters of the Wild and Scenic Hoback River (one of America’s Most Endangered Rivers in 2011 and 2012), American Rivers and our partners raised almost $9 million to buy back natural gas leases from a Houston-based energy company. The buyout—combined with existing federal legislation that bans new oil and gas leasing in the Wyoming Range—protects clean water, wildlife, and recreational opportunities for generations to come.

Wild and Scenic Rogue and Smith rivers, Oregon

In early January 2017, the U.S. Department of the Interior adopted a 20-year ban on new hard-rock mining on 100,000 acres of public lands and rivers, including these two rivers (on the list in 2015). American Rivers worked with a coalition of local, state and national advocates to advance the safeguards and set an important, bi-partisan precedent for protecting public lands. A bill making its way through Congress would permanently block mining near the Rogue and Smith, which are home to some of the strongest runs of salmon and steelhead in the lower 48.

St. Lawrence River, New York

Outdated dams were harming the St. Lawrence River and fish and wildlife habitat. Our America’s Most Endangered Rivers listing in 2016 shined a spotlight on the problem and helped secure a solution: The U.S. and Canadian governments approved a plan in 2017 to restore more than 64,000 acres of wetlands along the St. Lawrence. The plan will also improve water quality, support fisheries and biodiversity, control erosion, and bolster the region’s economy.

Holston River, Tennessee

Flowing 274 miles from the Blue Ridge Mountains in Virginia to the Tennessee River, the Holston hosts an ammunitions plant that leaked a carcinogenic, explosive compound into the groundwater for years. We included the Holston on our list of America’s Most Endangered Rivers in 2015 as a call to action. Good news: Local partners brought a successful lawsuit to force the plant to clean up the pollution. They won, and the work is scheduled to complete in 2020.