While running outside, one of the most exciting aspects is what you’ll see. The scenery of the outdoors doesn’t compare with the sight of a tv or mirror wall a treadmill provides indoors. Not to mention different seasons and weather conditions provide something new for runners to observe. The autumn months offer trails and roads paved with fall foliage, winter brings around ice and snow as the temperatures drop, and during the spring and summer, the trails and paths jolt to life again as plants bloom and people take advantage of warmer weather.

But there is one part of running outside that remains consistent throughout all seasons – litter. Whether running through a park, in a neighborhood, a busy street, or even a secluded trail, litter is always within view. I’ve attempted to do my part when running on the Capital Crescent or Rock Creek Park trails in D.C. but running shorts don’t always have the most plentiful of pocket space.

This is where plogging comes in.

Plogging is a fitness craze that first began in Sweden and is gaining popularity in the U.S. The word plogging comes from jogging and “plocka upp,” the Swedish word for ‘pick-up’. The activity involves individuals or groups of joggers with trash bags picking up pieces of garbage as they run, and since plogging involves running as well as squats, it can potentially provide a more intense workout.

The plogging trend is spreading across the U.S. thanks to its health and environmental benefits. Already, social media channels are full of photos of plogging hauls with the hashtag #plogging and river organizations are hosting plogging cleanup events.

With the weather getting warmer, life is returning to trails, sidewalks, and parks. With all those people outside there is bound to be more trash, but also more people to help pick it up. If you want to register or volunteer at clean-ups to try out plogging, National River Cleanup can help to make it easier and even supply groups with trash bags for their plog.

So, get out there and plog away!

Did you know rivers and streams provide much of our drinking water supply? This means that the water that you drink, cook and shower with, and use to clean your clothes and dishes, might come from a river.

Let’s celebrate the source of our drinking water and learn what we can do at home and in our community to help keep it clean.

Where does your drinking water come from?

The Environmental Protection Agency’s Drinking Water Mapping Application to Protect Source Waters is a great place to start. There, you can learn where your local water utility is getting your drinking water from. For example:

- If you live in Seattle, your water comes from the Cedar and Tolt rivers, where surrounding forests help protect water quality.

- If you live in New York, your water comes from the Delaware River basin.

- The 3.2 million residents of Minnesota’s Twin Cities get their water from the Mississippi River.

- Most of metro Atlanta’s 4.1 million residents get their water from the Chattahoochee and Flint rivers.

- The lifeline of the Colorado River sustains more than 36 million people across seven states, from Denver to Los Angeles.

- Three fourths of the drinking water for the Washington, DC metro region comes from the Potomac.

How can you help your drinking water source?

Get your hands dirty!

Find a local river cleanup through our National River Cleanup map. Not seeing one near you? Create your own cleanup with help from the organizers handbook (we can even send you trash bags).

Local river organizations have a variety of events, from tree planting to invasive plant removals, all of which help the water quality in your river. Using River Network’s searchable map, you can find and connect with over 6,000 groups across the U.S. that are working on local rivers.

Catch the rain

Rain barrels, which attach to downspouts, catch rainwater which would otherwise flow into sewers and over dirty streets, carrying pollution into local streams. Rain gardens are an attractive way to collect runoff and encourage groundwater recharge. These approaches work in concert with nature to collect and filter runoff, reduce flooding, and minimize pollution in our rivers and streams, all while helping to save money and energy.

Reduce your use

The average household’s leaks can account for more than 10,000 gallons of water wasted every year. | Pan Xiaozhen

One easy way to help protect your local rivers – use less of them! There are a few simple things you can do at home to ease the burden on your local water supply and save money in the process.

- Turn off the faucet while brushing your teeth.

- Only run the washing machine and dishwasher when you have a full load.

- Use a low flow shower head and faucet aerators.

- Fix leaks.

- Install a dual flush or low flow toilet, or put a conversion kit on your existing toilet.

- Don’t overwater your lawn or water during peak periods, and install rain sensors on irrigation systems.

- Install a rain barrel for outdoor watering.

- Plant a rain garden for catching stormwater runoff from your roof, driveway, and other hard surfaces.

- Monitor your water usage on your water bill and ask your local government about a home water audit.

- Share your knowledge about saving water through conservation and efficiency with your neighbors.

Every drop of water we drink connects us to a river. Together, we can make a difference for our rivers, ensuring clean water supplies for generations to come.

Deep into a multi-day trip on the Wild and Scenic Rio Grande in Big Bend National Park, I was swimming in the river. It was at the end of a hot day. Canyon walls rose around me and the cool currents felt good. And I wondered, am I in the U.S. or Mexico? I’d been told that the border is the middle of the deepest channel. But isn’t that constantly changing, on a monthly or weekly or hourly basis? When a river is a border, are boundaries fixed or fluid? People may care where the border is, but the river doesn’t. With all the noise around #BuildThatWall, what could we learn if we stopped for a minute to listen to the river?

We set up this trip in February to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act – the actual anniversary of the signing of this landmark law will be October 2, 2018. Senator Tom Udall from New Mexico joined us on the trip – his father Stewart Udall was Secretary of the Interior under President Johnson, who signed the Act. So did Ted Roosevelt IV, whose great-grandfather was the 26th President of the United States, and Nick Paumgarten, a writer from the New Yorker.

Nick’s New Yorker story does a great job capturing our adventure and describing some of the issues facing the river (read the article).

The New Yorker story covers the controversy of new border wall construction, as well as an idea that has been percolating for decades: the creation of a bi-national park to permanently safeguard public lands in Texas and Mexico. Similar to Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park connecting Montana and Canada, a park encompassing the Rio Grande would tie together critical ecosystems on a grand scale. It’s an alternative vision, the opposite of a wall. A bi-national park would be about connection and collaboration. It could symbolize abundance and courage and generosity. Not the fear and separation that the wall stands for.

We need big ideas like that. Our rivers and public lands deserve nothing less, especially now, when the Trump administration is lobbing new attacks daily. That is why American Rivers and our partners launched the 5,000 Miles of Wild® campaign to designate 5,000 new miles of Wild and Scenic Rivers nationwide, in celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. For our clean water, our shared natural heritage, our children. Our future.

River guide Austin Alvarado said something that stayed with me: “When you put the river first, everything else falls into place.” He meant that when you protect a river, we all end up getting what we need. People benefit more from a healthy river than a dead river. So what if we listened to the river? What if we put the river first? On the Rio Grande, and beyond?

Visit www.5000Miles.org to share your river story and tell Congress it’s time to protect 5,000 new miles of Wild and Scenic Rivers nationwide.

American Rivers had an opportunity to sit down with Chris Johnson from the Nooksack Wild & Scenic steering committee, to learn more about his experiences fishing on the Nooksack river.

Great to meet you Chris, could you tell us about yourself?

I’m a born-and-raised local Bellingham guy and a fisherman for almost my entire life. Having just crossed into my 62nd year on this planet, I’ve experienced some memorable days fishing our local waters. Unfortunately those days are fewer and farther between as North Puget Sound salmon and steelhead runs have declined, so too have the seasons to fish for them.

Can you talk about the changing seasons?

On the Nooksack River, the fishing season used to stay open for steelhead and bull trout until the end of March. Now the mainstem and the South Fork close at the end of January, with the North Fork closing a few weeks later on February 15.

Can you give us an example of what it used to be like on the river?

When I think about the “good ol’ days,” one particular day comes to mind. Not necessarily for the number of fish we caught, but for the beauty of a day spent in the Nooksack River watershed.

It was one March in the late 1980s when the river had been high and off-color for a while, and I had been checking the river daily once the snow level dropped. One day, I drove out to Nugent’s Corner the night before to really inspect the river—this was the pre-USGS streamflow website era—and while there was still a lot of flow, the river was beginning to clear up. I returned home, called a friend, and asked if he wanted to drift Highway 9 to Nugent’s Corner. Minutes after he said “yes,” I was in the driveway hooking up the drift boat and getting my gear together.

Early the next morning, we met at the take out, ran the shuttle, and launched the boat. There was still a lot of flow and a touch of color to the river so we made the decision to pull plugs with the hope of triggering an elusive wild, winter steelhead to strike. But after fishing the first four runs we had no fish and zero takes. Since there were already a lot of boats on the river and just about all of them were ahead of us, we realized we were not getting any coveted first water. But since steelheaders are optimistic people, we pushed on with all the hope and energy we could muster.

As we slid the boat down a riffle into the Shake Mill hole (the run is long gone, thanks to the dynamic and wild nature of the Nooksack drainage), we let out our lines and I began pulling on the oars, backing the plugs down the run. We had a small bucket we were trying to hit, which put us so tight to the high bank side that my right oar was hitting the rip rap. About halfway down the run, just as I noticed a big white rock next to me, the inside rod went off, shaking violently with an angry fish on the end. A mad scramble ensued as I grabbed the rod and we switched places. My buddy rowed across the river to the soft water, where we could safely land and release this hard fought Nooksack River wild steelhead.

“Nice fish,” I said as the steelhead came into view. “Ten or 12 pounds I’d guess, but I think we better do that again!”

I hopped back into the rower’s seat, headed back up to the top, and started the process all over again. We followed the same drill which yielded similar results. Right next to the white rock, tight to the bank, and the inside rod went off again. This time the steelhead went on a finger-burning run, cleared the water, but was much bigger and more aggressive in nature than the previous fish.

After a good battle, we ferried across the river and pulled her alongside the boat. She was an absolute beauty. All of 15 pounds and dime-bright, just days in the river from her migratory run through Puget Sound and the North Pacific Ocean. After we released her I thought we should see if we can replicate what just happened one more time.

Again, I hopped on the oars and pulled the boat back to the top for another pass. I slowly backed the plugs down the run and as we approached the white rock my pulse began to quicken. Could there be another fish there, after all these boats had fished through this run before us? Sure enough, as we slid next to the white rock, the rod buried once again. The fish made a long, slow, dogged run. Then it exploded at the surface, giving us a flash of its brute strength.

After a long stubborn tussle he came sliding alongside the boat, ready to be released. What we saw was a magnificent male wild steelhead, pushing the mid-twenties weight class. His jaw was just beginning to kipe and there was a beautiful rosy pink hue on his gill plate that tracked all the way down his lateral sides.

It was an absolute specimen and to this day the biggest steelhead I have ever caught. We caught no more fish the rest of the day, but that didn’t matter at all after the spoiled morning we just had. That one wild winter steelhead was well worth the price of admission.

What’s changed with the river since then?

Days and fish like that are becoming rarer as time passes. As the state fish of Washington, we need to do all that we can to protect wild steelhead and their habitat. Take the lower Nooksack, which has been hammered by civilization, from dikes and stormwater run-off to roads and loss of riparian vegetation, this infringement on their habitat has taken a toll on the native fish.

What more can be done to help?

While the lower and middle Nooksack River habitat improvements are limited (there are great habitat restoration efforts being completed by a variety of stakeholders), we still have an opportunity to permanently protect the upstream habitat, which is still somewhat intact and considered a vital connection to the anadromous life-cycle of steelhead and salmon. But without permanent protections for the Nooksack, the great habitat restoration efforts happening on the lower river would not be able to carry the recovery load if we lose the upstream habitat and spawning grounds for many of these fish.

For the last few years, I’ve been working as a volunteer with the goal of designating portions of the upper Nooksack River forks and tributaries as Wild & Scenic. My hope is that if we can achieve these lasting protections, they can aid in the recovery of wild steelhead and salmon, help populations rebound, and one day I could be back fishing the river in March, sliding the boat patiently down each run with the potential of connecting with another North Puget Sound wild winter steelhead.

[su_button url=”https://www.nooksackwildandscenic.com/” background=”#ef8c2d” size=”4″ center=”yes”]Sign the petition to support our Nooksack Wild & Scenic River campaign »[/su_button]

Over the last decade, momentum for restoring Sierra Nevada meadows has been building. The State of California and the U.S. Forest Service have both increasingly recognized the benefits of meadow restoration for California watersheds and are now committed to meadow restoration. Healthy meadows provide a suite of benefits including improved groundwater storage, enhanced water quality, reduced peak flood flows, and critical habitat.

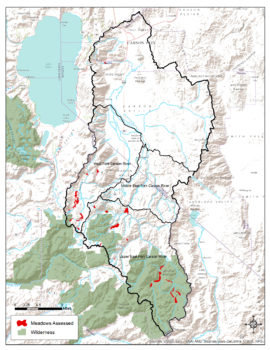

However, with an estimated 50 percent of the 191,000 acres of meadow in the Sierra (Sierra Meadows Strategy, 2016) degraded by human impacts, it is difficult to know where to start. To address this, in 2010, American Rivers partnered with UC Davis and the U.S. Forest Service to develop the Meadow Condition Scorecard, a rapid assessment method to quickly assess overall meadow condition and help identify meadows in need of restoration.

Since 2010, American Rivers has used this method in 11 watersheds throughout the Sierra. It has also been used by project partners including UC Davis and California Trout.

Last year, with funding from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, American Rivers completed scorecard assessments in two major Sierra watersheds, the Carson River and Truckee River. We assessed a total of 28 meadows in the Carson watershed and 30 meadows in the Truckee watershed for a total 58 meadows across 3380 acres. We then worked collaboratively with diverse stakeholders to prioritize the most important sites for restoration based on the scorecard data and other factors like water supply and wildlife benefits. The results of these assessments and others are available via the UC Davis Sierra Nevada Meadows Data Clearinghouse. For the full reports, see the links below.

Restoring Carson Meadows: Assessment and Prioritization

Restoring Truckee Meadows: Assessment and Prioritization

The meadow scorecard assessments have been an important tool for collaboratively identifying top-priority projects and galvanizing support. For example, as a result of this process in the Carson and Truckee watersheds, American Rivers and partners identified 12 priority meadows and have already raised $455,000 to restore the first four sites.

We plan to continue to use the scorecard to identify priority projects and bolster support for meadow restoration, including completing a new assessment of wilderness meadows in Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks this coming summer.

Over the last week, those of us who eat, sleep, and drink Colorado River issues have watched with alternating measures of surprise, concern, and alarm as water users from the Upper Basin states publicly called out the operators of the Central Arizona Project (CAP) for “gaming” reservoir levels to maximize water deliveries to Arizona. The worry is that CAP’s efforts to find a “sweet spot” in managing the Colorado River has the effects of undoing nearly a decade of collaborative conservation successes and threatens to pull the entire Basin into shortage more quickly than is already likely.

Media coverage of this dustup has been welcome, highlighting the complexity and conflicting motivations at the heart of efforts to manage the Colorado River as a water supply for seven states and 40-plus million people. The states and major water users along the river agreed in 2007 to a set of guidelines that spelled out collaborative responses to drought and shortages in water supply. But these guidelines don’t resolve the tension between an ethic of “we’re all in it together” and the long-practiced tendency of each state to maximize their own water use. More critically, the guidelines are a good effort to respond to short-term drought, but deftly avoid the substantive management changes needed to address permanently diminished flows associated with long-term aridity.

Conflict between states and water users is regrettable, but more so, there is a missed opportunity within ongoing multi-state negotiations to fully acknowledge what all of us privately admit… there isn’t going to be enough water in the Colorado River in the future to fulfill all of the previously made promises. If the Colorado basin ever really provided a reliable fifteen to seventeen million-acre-foot (MAF) supply, those days were brief, and they are long gone. The consensus of climate science and hydrology points toward a future in which Colorado River flows total 12 MAF or less, perhaps as low as 9 MAF. The real problem isn’t one water user striving to achieve a “sweet spot” in reservoir levels to maximize its own water use; it’s the failure so far of the basin states to adjust to the new hydrology. Region-wide aridity and a warming climate just might force that hand for them.

In this regard, Arizona certainly could be doing more. Individual users of Colorado River water, some of the major urban water providers, and an irrigation district or two, have shown innovation and commitment to conserving water and creating more flexible tools for sharing their water resources. Likewise, cities in southern Nevada and southern California have demonstrated real foresight, either in reducing demand or developing resilient local water supplies as alternatives to uncertain and declining Colorado River imports. But as a whole, the states that share the river haven’t yet shown a full commitment to solving the underlying problem of getting by with a smaller share of Colorado River water.

If there’s a silver lining in last week’s airing of dirty laundry, maybe, just maybe, it’s in the way the family feud has highlighted our need to get to the real issues. As the basin looks toward negotiations around a new set of operating guidelines to succeed those adopted in 2007, let’s hope they can bring a spirit of innovation and honest, intentional, collaboration to meet this challenge.

Riparian floodplains are some of the most fertile agricultural lands in the world. Nutrients are carried from upriver and deposited in the floodplain during high flows. Some of the oldest civilizations were established in floodplains due to the productivity of the soil.

Unfortunately, farming and living in these floodplains comes at a cost. The process involved in depositing those massive loads of nutrients on the land requires flooding. This, of course, can be destructive. We try to battle these floods with our man-made infrastructure, but sometimes our best designs are not good enough to keep the floodwaters off of our developed lands. Sometimes it costs more to try to keep farming in these flooded areas than it costs to restore the land to its historical ecosystem.

In the Big Sunflower River Basin, approximately 290,000 acres of natural areas are at risk of being negatively impacted by the Yazoo Pumps. Of these areas, over 220,000 are state or federally-owned. This means taxpayer money was used to protect and restore those acres. Approximately 40,000 acres were added to that sum over the past 13 years. Depending on the value of the land, the recently protected lands alone likely cost $60 to 80 million to purchase and restore. Some may ask, “Why spend that money to convert it back to a natural area?”

Conservation Easements and the Farm Bill

Through the Farm Bill and other federal programs, landowners can apply for their land to be enrolled in permanent wetland or floodplain easements. The Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) then purchases the development rights to the land. In most cases, the lands enrolled in these easements are lands that are highly susceptible to flooding and erosion and have become difficult to continue farming. NRCS then pays the landowner a fair price for land that would be difficult to sell due to the flooding and erosion. Then the land is restored to a more natural system that provides numerous benefits including fish and wildlife habitat, floodwater storage, recreation and nutrient removal.

Digging into Maps

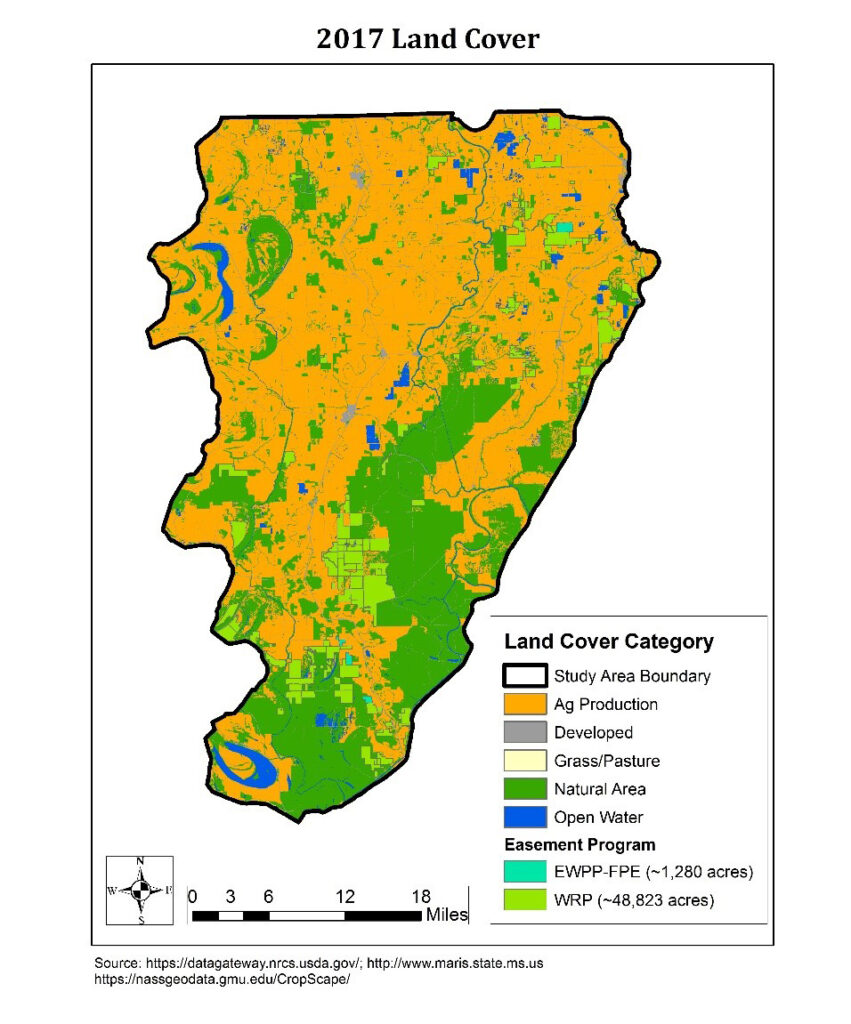

Approximately 290,000 acres of natural areas cover the Yazoo Pump Study Area. Of those, about 200,000 acres are wetlands that could be negatively impacted if the pumps are installed. Further, taxpayer dollars invested in the restoration of as many as 50,000 acres of easements could be negated.

Currently, the Yazoo Pumps project proposal lists a 926,000-acre area as the Yazoo Backwater Study Area, but during a major flood in 2011, approximately 160,000 acres of the pump area flooded. When looking at some maps, a few questions came to mind:

- If we assume the entire study area is affected by the Yazoo Pumps, how might they impact conservation land protected by taxpayer dollars?

- How will the Yazoo Pumps impact agricultural land in the entire study area?

- On the other hand, if only 160,000 acres are pumped, which of the lands in question would actually be affected by the project?

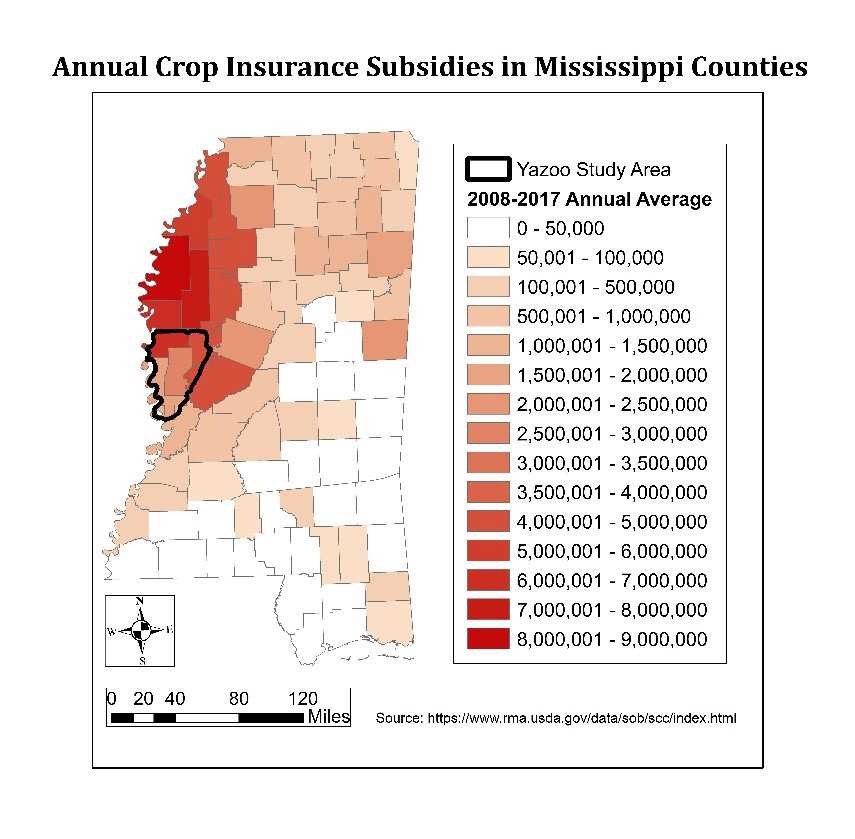

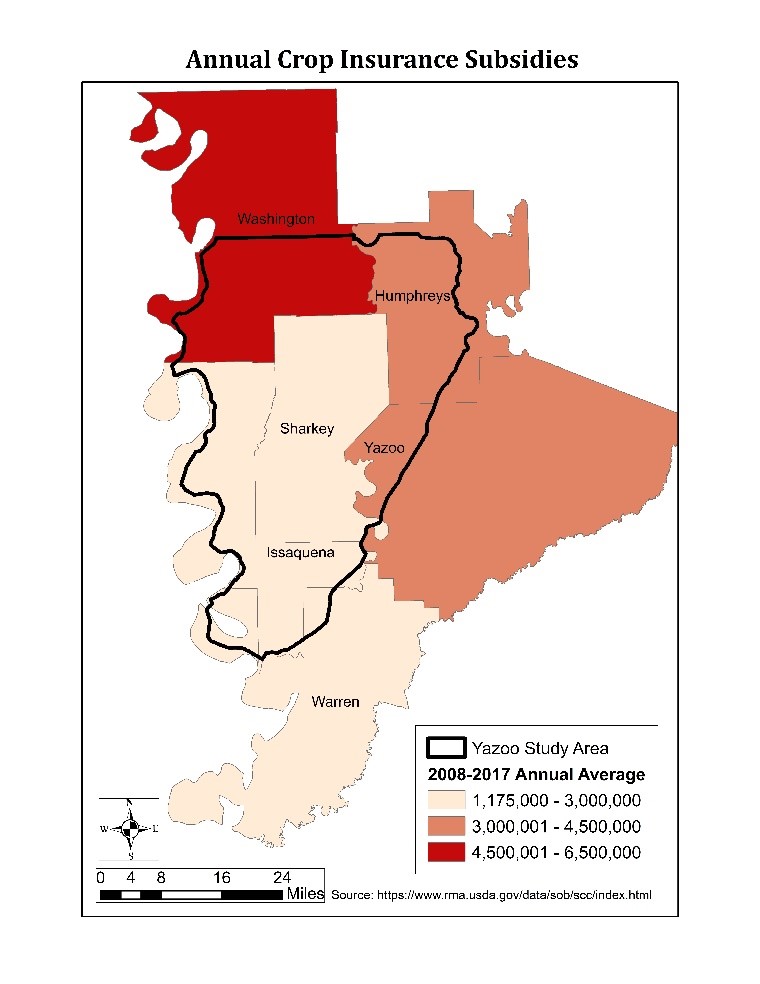

Scenario One: Pumping During All Flood Events

Some people believe that the pumps will decrease the overall risk of farming in the floodplain. The map below reveals that the Mississippi counties located in the Mississippi Delta, where most of the state’s row crop agriculture is located, receive the most crop insurance subsidies on an annual basis. The pumps would be located inside the study area as shown in the maps below. It is possible the pumps would then reduce the amount taxpayers must spend to relieve the flooding disasters in that area, but does the reduction in crop insurance subsidies pay for the pumps? No. Subsidies within the pumped area total less than $10 million each year. If the pumps cost over $300 million to construct, then it will take at least 30 years to pay for the pumps. However, by that time, the pumps will have cost more for repairs and management. Furthermore, the pumps will not relieve crop loss entirely. There will still be other problems leading to crop loss and the need for crop insurance, so we can assume there will still be millions of dollars spent on crop insurance in this area with or without the pumps.

Maps showing annual agricultural crop insurance subsidies (in dollars) in all Mississippi counties and then zoomed into the Yazoo Pumps study area.

On top of the fact that this argument for building the Yazoo Pumps doesn’t make sense financially, draining the entire pump area will most definitely impact a large portion of the wetlands. At that point, we would no doubt see detrimental impacts to the natural area that cannot be quantified financially. Over 200,000 acres of wetlands would be drained to some extent, and the investment of over $100 million of taxpayer money in conservation lands would be completely negated.

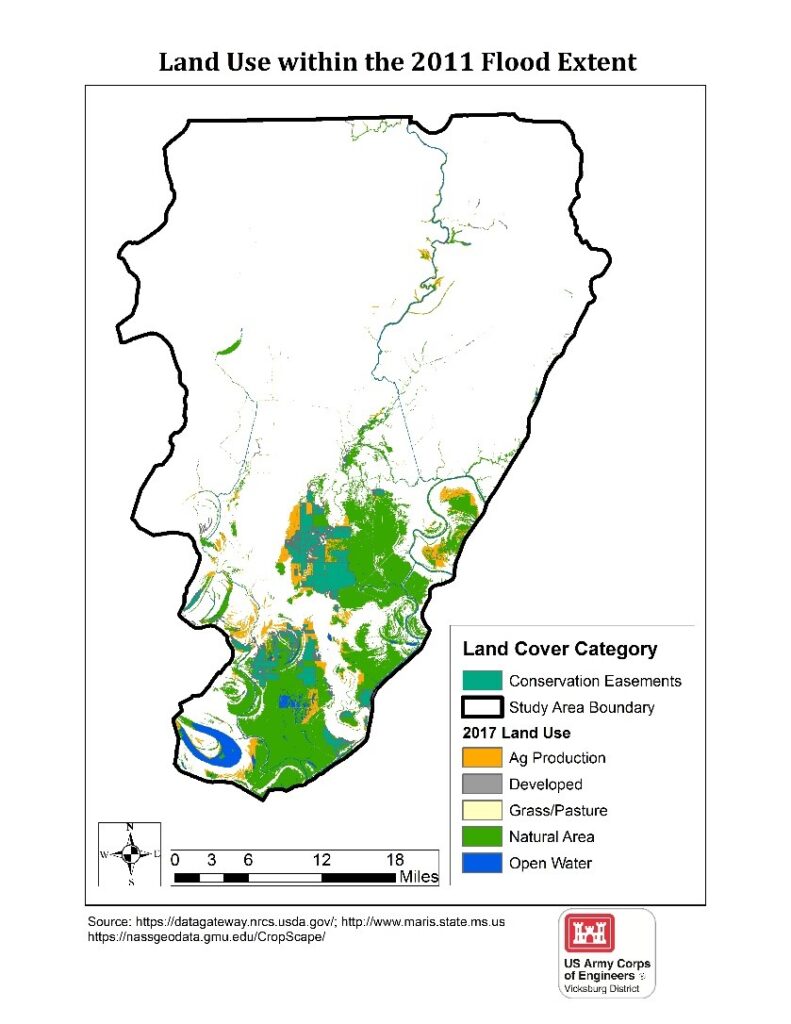

Scenario Two: Pumping During Major Floods Only

In the second pumping scenario, the Yazoo Pumps are turned on only during large flood events like the 2011 flood. This scenario presents an even worse financial investment. In 2011, the Mississippi River spilled over its banks and destroyed homes, farmland and infrastructure. During that flood, approximately 160,000 acres of the pump area was flooded.

Having pumps in place could have drained some of the water, but what type of land would it have drained?

As the map below reveals, most of the flooded area was wetland. Only 19,000 acres of the flooded area is currently in agricultural production. That means only 12 percent of the flooded area would have been cropland in need of protection, while 139,000 acres of natural wetlands and open water would have been unnaturally drained. If less than 20,000 acres of cropland are protected when turning on the pumps during floods, then the investment in the pumps will never be paid off.

Map showing the types of lands impacted by the 2011 flood in the vicinity of the proposed Yazoo Pumps.

Impacts on People

Another issue that has not been addressed is the impact that the pumps will have on developed areas and the people who live nearby. Two counties, Issaquena and Sharkey, make up 87 percent of the economic base of the pump area. Those two counties combined contain fewer than 6,000 people. The population in the area has been consistently declining in recent decades. Furthermore, the two counties contain a little over 200 farms, most of which are large industrial operations harvesting thousands of acres each. Therefore, the investment in the pumps would not aid many farmers, and most of the benefits would go toward a select number of those farmers.

No matter how we look at this $300-million investment, it is not a good use of taxpayer dollars.

If the pumps drain the entire study area, it will cause irreplaceable damages to wetlands and not save enough money in insurance and disaster relief. If the pumps are turned on only during flood events and drain only a portion of the study area, very few acres of crops will benefit while most of the wetlands will be drained.

Although floodplains are some of the most fertile lands in the world, sometimes it is better to restore them to their natural state rather than face the risks involved with farming them. Many taxpayers have realized this in the Big Sunflower River Basin and sought to protect those resources. Let’s not drain their investments.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/4999/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”4″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

Guest blog in celebration of World Fish Migration Day by Matthew B. Ogburn.

I’ve only seen river herring in the Patapsco River once. A dozen silver flashes, finning among rocks on a warm spring day along the Grist Mill Trail upstream of Orange Grove. Place names hint of the mills, iron forges, and villages that once filled the Patapsco Valley.

Trains rumble by along tracks on the valley wall and planes fly overhead every few minutes on final approach to Baltimore/Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport. Guinness is building its new brewery and barrel house just downstream. And Bloede Dam stands in the way of fish migrating upstream to spawning grounds, the birthplace of their ancestors for millennia.

The Alewife and the Blueback Herring (two fishes collectively known as ‘river herring’) are born in spring into the warming waters of rivers and streams flowing into Chesapeake Bay. Alewife like the water cool, arriving in March and staying through April. Blueback Herring prefer the warmer waters of April and May. Like salmon, they are anadromous fish that migrate from the ocean into freshwater streams to spawn. Unlike the stereotypical salmon which dies after spawning, many river herring migrate repeatedly between the ocean and freshwater streams to spawn for several years.

Young river herring spend much of their first year in the protected waters of tidal rivers and marshes. As the cold of winter arrives, they swim to the relatively warm waters of the mid-Atlantic continental shelf. Maturing between ages 3 to 5, they may live to an age of 8 years or more.

The Alewife returned to Patapsco River a few weeks ago. Among the many returnees were several fish tagged by my research team from the Fish and Invertebrate Ecology Lab at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center. (My team is on the river every week and sees many more herring than I do!) We use Passive Integrated Transponders, or PIT tags, which are the same ‘microchips’ that your dog or cat may have, to track the migrating fish. These are the first river herring recorded returning to the Patapsco for multiple spawning seasons!

It’s an exciting finding, because it confirms that the same individuals return to the river each year. These fish, or their kin that we tag in 2018, will be among the first in over 100 years to access up to 65 miles of habitat upstream of Bloede Dam. Thirty-five feet tall and an engineering marvel of its time, the long-dormant hydropower dam will be removed later this year. It is another step in the transformation of Patapsco Valley from industrial center to scenic State Park.

Will the herring pass the site of Bloede Dam? Will they pass the sites of Simkins Dam (removed in 2011) and Union Dam (removed in 2010)? Will they reach Daniel’s Dam, soon to be the last remaining major dam on the mainstem Patapsco River, or even use its fish ladder to move further upstream? We’ll be watching and waiting for them, learning the lessons individual fish have to teach us about the resiliency of two species that have survived despite a multitude of threats.

River herring are still in the Patapsco River because a few herring avoided the nets of foreign and then American fishing fleets that decimated populations in the 1950s-70s. Today, some fish are still caught accidentally in offshore fisheries, but efforts are in place to minimize those impacts. After migrating into Chesapeake Bay to the mouth of Patapsco River, they swim past Ft. McHenry and through the industrial Port of Baltimore before entering fresh water. Generations of herring have persevered in the degraded lower reaches of the river, where water power made the Patapsco Valley an engine of the Industrial Revolution.

Will river herring populations in the Patapsco River stage a comeback after the removal of Bloede Dam? Spawning runs 10 times greater occur in the Choptank River, much of which has never been dammed, and Marshyhope Creek, where a centuries-old dam washed out in 1935, giving hope that access to habitat will spur a recovery. Whether or not herring populations increase, removing Bloede Dam is a major milestone in the restoration of the Patapsco River and its valley, a conservation success story in the heart of the Washington-Baltimore Metropolitan Area.

Author: Matthew B. Ogburn

Dr. Matthew Ogburn is a Principal Investigator and Research Scientist at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center in Edgewater, Maryland. Matt specializes in fish and invertebrate ecology.

This guest blog by John Ruskey, with Quapaw Canoe Company, is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series on the Big Sunflower River.

This river has the blues! Besides the many blues and gospel musicians who were born and baptized along its banks, its mussel shell beds, which are reported to be the richest such biota in the world, seem to be in constant danger of overzealous engineering. The Sunflower River has been neglected, dumped upon and over-worked — so much that American Rivers has proclaimed it to be America’s “Most Endangered River” in 2018.

The good news is that its forests constitute the largest bottomland hardwood forests in the National Forest system (they also produce the highest carbon-sequestration of any forests in North America!), and its banks are home to every creature found native to the Mississippi Delta, winged, webbed, or otherwise. It’s a beautiful place to get away, to reflect a moment on the rivers and woods of America, to walk along its banks, to paddle its waters, to enjoy its primeval scenery. Most importantly, it’s home to all of us who live on or near its banks, and second home to many others who love it from a distance. Shouldn’t we be taking better care of our lonely muddy river — the little lonely river with a bad case of the blues?

Natural and Cultural Description:

The Sunflower River is sometimes difficult to access, in part because it is carved out of the deep mud of the Lower Mississippi Alluvial Valley. Nevertheless it is well worth the effort to explore. Paddlers are rewarded with abundant birds, amphibians and mammals, deep woods, endless wetlands, and the rich culture of the Mississippi Delta. How many rivers can you put-in near the Delta Blues Museum (Clarksdale), paddle behind the most active juke joint in the world (Red’s in Clarksdale), meander though the “birthplace” of the blues (Dockery Plantation), visit another legendary juke joint Club Ebony (BB King’s haunt in Indianola), and end up near the birthplace of Muddy Waters (Rolling Fork)?

The Sunflower is the Mississippi Delta. If a rain drop falls in the Delta most likely it enters the Big Sun somewhere in its 250 mile north-south journey. It receives all waters good and bad from Friars Point, Clarksdale, Cleveland, Indianola, Leland, Greenville, Rolling Fork, and Mayersville. The only major Delta populations it doesn’t drain are Tunica, Greenwood, and Belzoni. Its tributaries include the Hushpuckena, the Quiver River, Bogue Phalia, Silver River, and due to some radical canal work, Deer Creek and Steele Bayou. The Little Sunflower, and some minor bayous and chutes are considered its “distributaries,” waterways that carry its excesses during high water. It is sometimes connected overhead out of its drainage area via Moon Lake and the Yazoo Pass to the Coldwater River and points North and East, but only after torrential rainfall or during the highest of river levels. Of course, during severe flooding, the entire Delta goes under water and then you could really say “the river connects us all!”

450 species of fish and wildlife depend on the Big Sunflower River, including belted Kingfishers. | Stephen Kirkpatrick

The Sunflower River is born in the bayous and lakes of Northern Coahoma County and meanders South some 250 miles through the Yazoo-Mississippi Delta paralleling the Mississippi River on the West and the Yazoo on the East, (with which it confluences with 10 miles above Vicksburg). A small but dynamic river, once forested, now mostly bordered by fields, the Sunflower is a rich habitat for all creatures native to the region, including black bear and panther. Its muddy current averages 2100 cfs (cubic feet per second) at Sunflower, 3461 cfs at the mouth of Bogue Phalia, and approximately 4500 cfs where it empties into the Yazoo River at Steele Bayou. Its drainage includes most or all of Coahoma, Bolivar, Sunflower, Washington, Sharkey, and Issaquena Counties, some 3,689 square miles, inhabited by 133,075 people (2017 estimate, US Census).

The Sunflower and the Yazoo parallel each other (and not coincidentally the Mississippi River) for the majority of their North-to-South journey, but come from widely different origins. While the Sunflower emerges from the bayous of the North Delta, the Yazoo gurgles out of the Kudzu-covered Piney forests of the Mississippi “Hill” Country, in the form of the Coldwater River. Later it merges with the Tallahatchie (Bobby Gentry: Ode to Bille Joe), and then at Greenwood meets the Yalobusha to form the Yazoo. It also passes through Sledge (home of Charlie Pride), Marks, and Yazoo City. Greenwood was once the cotton stock market capital of the world, and Robert Johnson was reportedly poisoned in a nearby juke joint. Emmet Till was murdered on one of its bayous, igniting the stormiest period of the Civil Rights era.

All Mississippi rivers have the blues to some extent, but the Sunflower has the blues worse than any other. In its journey through the Delta, the Sunflower winds through the layers of mud and history that gave the world its first great blues singer (Charlie Patton, Dockery Plantation), the first mechanized cotton picker (Hopson Plantation), its oldest African-American founded community (Mound Bayou), rural Civil Rights era leaders (Fanny Lou Hamer, Sunflower County; Aaron Henry, Clarksdale), the Teddy Bear (President Theodore Roosevelt was in the Delta National Forest (reportedly somewhere near Little Sunflower Recreation Area) hunting bears when the idea of the teddy bear toy was created.), King of the Chicago Blues (Muddy Waters, born in Rolling Fork, lived 25 years at Stovall) and the renowned ambassador of the blues (B.B. King, Indianola). The Rev. C.L. Franklin (Aretha’s Father) is just one of many who were baptized in her muddy waters. Bessie Smith died at the G.T. Thomas Hospital which sits on her banks in Clarksdale (now the Riverside Hotel). Today you can hear live blues along the river at juke joints Red’s and Ground Zero Blues Club, and learn about the African American history that gave birth to this earth-shaking music at the Delta Blues Museum (Clarksdale) and the BB King Museum (Indianola). Legendary woodsman, Holt Collier (1846-1936), who cornered the Teddy Bear, reported its waters to run clear and clean, and Roosevelt started each day of the hunt with a cold-water swim. One of our long-term objectives is to make the waters safe once again for fishing and swimming. What would Roosevelt think if he returned to the deep forested lands he once hunted in and found their wetlands had been drained of water?

Don’t look for sandbars on this river. You will encounter nothing but thick, rich Mississippi alluvial floodplain soil, and the fields and towns and forests adjacent. Exceptional wildlife, especially raptors and amphibians. Muddy banks make for muddy landings, muddy picnics, muddy camps. In high water the mud is all hidden. But in low water be ready for climbing and descending steep slippery banks of chocolate goo as you enter and exit the waterway.

Of course, the end of one river is just the beginning of another, and so the Sunflower becomes a tributary of the Yazoo River at Steele Bayou. Not far downstream the Yazoo gets swallowed by the mother river, the Mighty Mississippi. There is an outdated plan to build the world’s largest freshwater pumps where the Sunflower joins the Yazoo, the so-called “Yazoo Pumps.” We in the Delta feel the effects of the problem the pumps are supposed to fix, that is “backwater” building up within the Mississippi Delta. We paddlers have some thoughts about this and the water situation everywhere, the lack of good water, the disappearing wetlands, the violent shifts of water levels from drought to flood, from extremely low water levels, to catastrophic flooding on all rivers in the middle of America. Why is this happening? In part because more rain is falling when it rains. In part because we keep cutting off wetlands, like the Mississippi Delta, or building parking lots or neighborhoods, or increasing our farmlands in places where the river used to naturally expand, and its excess waters be absorbed in.

I am but a canoe builder and river guide, and leader of a small group of adventurers, the Mighty Quapaws. But we do know the Sunflower river better than anyone else, if nothing else for the simple fact that we are the only people that actually get out and paddle it. Poor neglected rivers. They have become the closet you stuff all your unwanted things in — where your guests can’t see them. But what if your guests did see them? Then you’d start keeping it a little neater, wouldn’t you? And that’s what we are hoping with the Big Sunflower – we are hoping that these explorations and writings will take some of the fear out of the mud and trashy banks, and add a little respect and recognition of the beauty and great expressions of life – and that more people will get out and paddle it. As more people paddle, maybe the people who dump things over the bank will be less inclined to do so — and those who would build giant expensive pumps — and who knows, maybe with the attention of others they’ll even clean up some of the mess they made last year.

It’s time to stop this terrible ‘Yazoo Pumps’ project and protect the Big Sunflower and it’s rich history once and for all.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/4999/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”4″ center=”yes”]Take action »[/su_button]

Where can you paddle the Sunflower River?

There are many places along the 250-mile length of the Sunflower River to access and paddle, but the best spots are found around Clarksdale and Rolling Fork. See below for complete listing and links to water trails in Clarksdale, Anguilla, and Rolling Fork. Canoe, kayak and paddle board are all suitable vessels.

Clarksdale:

In the Clarksdale area, you can do a round trip from downtown, paddle upstream as far as you feel like and then turnaround. The Quapaw Canoe Company is a good place to do this from for easy parking, access, maps, and canoes, kayaks and paddle boards for rent. www.island63.com

There is also a beautiful 3 mile paddle (approx 1 hr.) into downtown from the Friars Point Bridge. Or take an afternoon and put in near Clover Hill on the Farrell-Eagle’s Nest Road, 10 miles total (approx 4 hrs). http://lowerdelta.org/paddling-trails/sunflower-river/

Hopson Plantation/Shack Up Inn: Start out near Red’s Juke Joint in downtown Clarksdale and paddle 5 miles downstream for a takeout at the Hopson Bridge, directly behind Friend of the Sunflower River supporting business Shack Up Inn.

Sunflower:

In Sunflower, put in behind the Library and do a round trip paddle, first upstream, you can make an interesting foray up to the mouth of the Hushpuckena River, and then float back into town. (like climbing the mountain: do the hard work first!)

Indianola:

Put in at the confluence of the Quiver River, approx 8 mile paddle to the Hwy 49 Bridge below town. Walk 2 miles north into town to reach Club Ebony, BB King’s favorite juke joint. The phenomenal BB King Museum is located nearby.

Anguilla:

Boat Ramp at the Hwy 14 bridge. Do a round trip, or make a day (or overnight) 14 mile paddle into Delta National Forest, the largest bottomland hardwood forest in the National Forest system. http://lowerdelta.org/paddling-trails/big-sunflower/

Near Rolling Fork/Holly Bluff:

Good ramp on the old channel of the river off highway 16. Paddle upstream past the distributary Little Sunflower River, and meander deeper and deeper into the woods. Round trip: go as far as you feel like paddling, then turn around and return to your vehicle.

Little Sunflower River: Put in at the boat launch off the 433 (Spanish Fort Road) deep in Delta National Forest (the largest bottomland hardwood forest in the National Forest system) and explore the same woods legendary hunting guide Holt Collier frequented. http://lowerdelta.org/paddling-trails/little-sunflower/

Near Eagle Lake:

Steele Bayou Confluence: put in at the Steele Bayou Control Structure and paddle upstream ½ mile to the confluence of Steel Bayou, where steamboats used to start their journey up into the frontier Mississippi Delta.

Yazoo River Confluence: put in at the Steele Bayou Control Structure for a one-mile paddle to the mouth of the Big Sun at the Yazoo, the “River of Death.” Enquire about further paddling options down the Yazoo River.

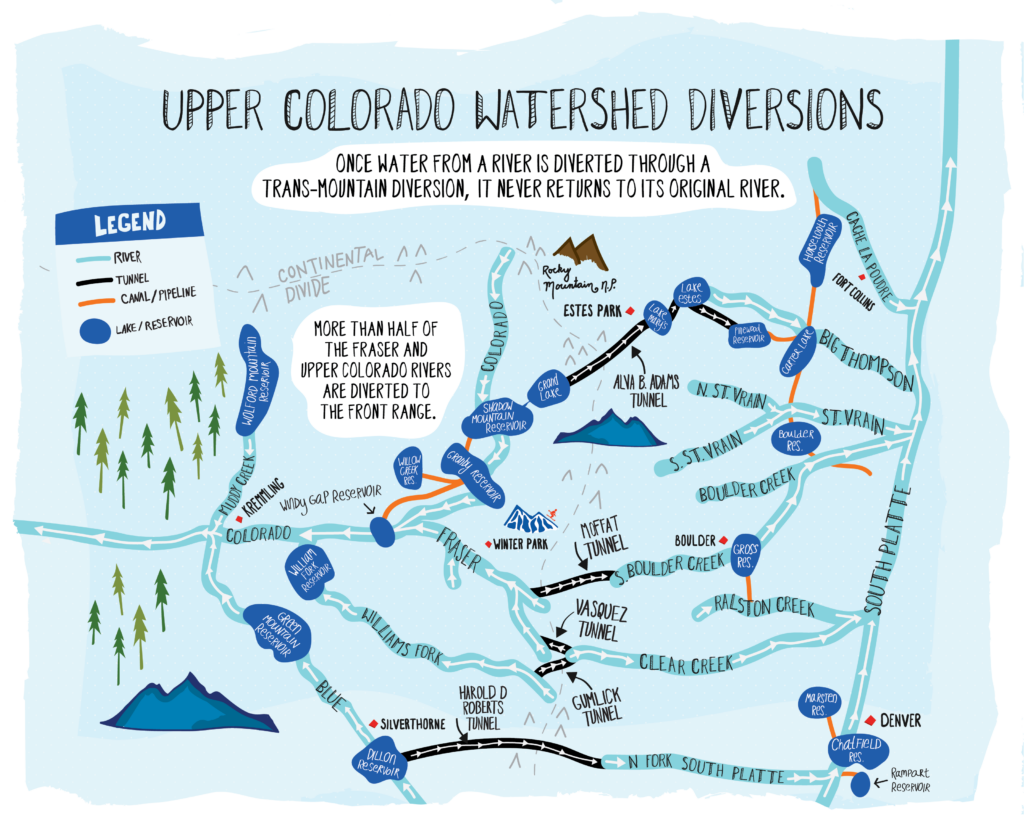

Rivers are the lifelines of Colorado’s economy, environment, and lifestyle. They touch everyone in our state, providing most of our clean, safe, and reliable drinking water; supporting our thriving farms and ranches; and contributing to culture, heritage, and recreation — everything from world-class fishing, paddling, and scenery — drawing visitors from around the world.

Colorado’s rivers provide so much to each of us, but do we really know enough about them?

Colorado’s rivers sustain our economy and quality of life, however our state’s lingering aridity and variable climate does not guarantee enough water will be in the right place at the right time for people or wildlife. The journey of water and the ways we’ve engineered our river systems to move water to where it is needed is complicated.

As Colorado developed, the Front Range grew beyond what nearby available water sources could reliably supply. Envisioning a future of water scarcity, Front Range water providers secured significant Western Slope water rights, allowing them to pipe and pump Western Slope water east across the Continental Divide to support the water needs of the Front Range. These trans-basin diversions permanently remove water from one basin, depriving downstream ecosystems and communities of water that would have naturally flowed through them.

Rivers supply the majority of Colorado’s drinking water. Unfortunately, today our rivers are under strain from high water demands and limited supplies. Colorado’s population is rapidly increasing, topping 5.6 million in 2017, and experts predict our state’s population could double in 30 years. Our rivers are already overworked providing for current demands, let alone for future growth.

Today, American Rivers and Audubon Rockies released “Do You Know Your Water, Colorado?” a resource to illustrate the long, complicated journey a drop of water has from its home in a river to your tap. Take a look, and explore how the rivers we love are connected to our clean, safe, reliable drinking water, and ways you can step up to protect the rivers and places we love in Colorado.

In many ways, water ties our state together, but managing water in Colorado has never been easy. With a changing climate, growing population, and numerous competing needs, managing Colorado’s water will not get any less challenging in the future. It’s more important than ever that we all understand where our water comes from, and what we can do to preserve our critical water resources.

In 2015, Colorado’s first Water Plan was signed, establishing the first holistic approach to managing the state’s water. Colorado’s Water Plan offers solutions to water uncertainty by charting a collaborative path forward towards water security for people and the environment. The Plan provides a blueprint for improving water conservation, using land smartly, storing and sharing water more efficiently, and ensuring our rivers and natural places have the water they need to stay healthy and to support Colorado’s vibrant recreation economy and way of life. It is now up to Colorado to put the Water Plan into meaningful action.

Coloradans know what makes our state so great – our rivers. We must meet future water demands without sacrificing our rivers and the wildlife, communities and economies they support. Our communities, economies, environment, and drinking water depend on all of us working together. Can our rivers count on you to help move Colorado’s water future forward?

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/5080/petition/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”4″ center=”yes”]Take Action »[/su_button]

This week, after seven years of opposition to a hydropower proposal put forth by the Snohomish County Public Utility District (SnoPUD) for the South Fork Skykomish River, local activists, tribes, paddlers, river recreationists, and anglers got some good news at the April 10 SnoPUD meeting, when the SnoPUD commission and staff agreed to cancel the Sunset Falls hydropower project and request the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) to close the docket on the current application.

“I don’t see a need at the moment for Sunset Falls,” said Commissioner Kathleen Vaughn at the April 10 meeting. The announcement was met with a resounding applause from the audience, which was packed with local residents and activists, whom for years have been vocal in their opposition to the project.

“What the IRP (Integrated Resource Plan) makes pretty clear is that there isn’t a need for a resource like Sunset Falls,” said SnoPUD CEO/general manager Craig Collar, “particularly from an energy standpoint, but also from a capacity standpoint, anywhere in the near future.”

SnoPUD’s Integrated Resource Plan is a long-term strategy regarding future energy resources and provides an action plan for the future. Once the IRP is adopted at the upcoming May 2018 meeting, the Sunset Falls project will be officially cancelled.

The announcement came just one year after the South Fork Skykomish was named among America’s Most Endangered Rivers® of 2017, the second time it’s landed on the list (first time was in 2012).

The proposal for the run-of-river hydroelectric facility at the Sunset and Canyon Falls reach would have rerouted water from a 1.1-mile stretch of the river sending it through a roughly 2,200-foot underground tunnel to a powerhouse at the base of Sunset Falls, thus reducing Sunset and Canyon Falls to a trickle.

The proposed project would have adversely impacted the downstream migration of salmon and steelhead smolts in the spring. According to Tulalip Tribe data, the habitat above the falls represents upwards of 30% of the Chinook natural origin spawners in the Skykomish population and 20% of the Chinook production within the entire Snohomish basin. Chinook salmon are critical to our struggling Southern Resident Killer Whale populations.

Of course, the opposition to this dam goes well beyond just a wild fish perspective. Because of outstanding fish, wildlife, recreation, and scenic values, the South Fork Skykomish has been singled out by a variety of state, regional, and federal agencies for protection. In 1990, it was recommended by the Forest Service as suitable for Wild and Scenic designation. The Northwest Power and Conservation Council identified it as a Protected Area from hydropower development. And it is recognized as the only Puget Sound river in the Washington State Scenic River system. Add to that the power generated from the project would be minimum and come at a high price to ratepayers, operating at a loss for the first 30 years, and the project just doesn’t make sense.

“This is a major victory for everyone who values our region’s healthy, free-flowing rivers,” said Wendy McDermott, Director of the Puget Sound and Columbia Basin for American Rivers. “Thanks to overwhelming public support and determined local activists, the South Fork Skykomish River has gone from ‘most endangered’ to ‘saved’. I commend the Snohomish PUD for making this prudent decision today.”

Although there was overwhelming opposition from locals, the general public, and tribes, local resident and activist Lora Cox was singled out by the SnoPUD staff and commissioners at the meeting for her dedication and work against the hydropower proposal. In a time when the political and conservation landscape is full of hyperbole and sometimes skewed facts, there is a refreshing lesson to be learned from the way Cox approached advocacy, as indicated by Collar and the commissioners.

“I’d like to recognize one stakeholder in particular: Lora Cox,” said Collar. “Lora is no fan of the project and we heard from her more than anyone else. Lora was always polite, always respectful, and she took the time to engage with staff and ask questions. She was receptive to feedback and worked hard to understand this project and engaged with staff in a very graceful way, which we appreciated.”

“I can’t speak about what this means to other stakeholders,” said Cox, “but this was a deeply personal debt that I tried very hard to pay,” she said. The debt she references was a lost battle she fought years ago in opposition to a dam on the Stanislaus River in Northern California. “Little did I know the effort would be all-consuming, requiring huge amounts of time, mental energy, patience, and a bit of money. But the Skykomish River will remain free flowing for quite a while.”

She added, “SnoPUD leadership and commissioners deserve credit for reassessing their realistic need for the minimal amount of power the project would have produced and for wisely deciding to abandon the project. For a public utility to do that is almost unheard of.”

Cape Town, South Africa, could be the first modern city in the world to run out of water due to explosive population growth and severe drought, intensified by climate change. Since word of the shortage first hit U.S. newspapers in February, “Day Zero” — when the city’s reservoirs run dry and the municipal water system essentially shuts down — has been pushed from April to July and perhaps beyond thanks to Capetonians’ emergency water-saving measures. But if and when the city is forced to shut off its taps, more than 4 million people could be rationed to 6.6 gallons of water per day — just enough for basic health and hygiene.

I sat down with American Rivers’ Senior Vice President of Conservation, Chris Williams, to hear why he isn’t surprised by the news out of Cape Town, why it’s a big deal and how American Rivers is working across the country to make sure our communities are thinking and acting in smart ways when it comes to water in the era of climate change.

A dry reservoir behind Theewaterskloof Dam near Villiersdorp, Western Cape, South Africa, which serves 41% of the water storage capacity available to Cape Town. | Photo: 6000.co.za [FlickrCC]

Why is it important to pay attention to what’s happening in Cape Town?

Because it’s situations like Cape Town’s that folks in the water world have been sounding alarms about for a long time. In many parts of the world, water supplies are under increasing pressure from growing human population, demographic changes and climate change, which is changing the rules by which rivers, rain and snowfall, and annual storms have operated for thousands of years. Under most climate change scenarios, dry places are going to get drier, wet places are going to get wetter, and times of drought and plenty will be increasingly unpredictable. So, cities and agricultural areas that are in fairly dry parts of the planet — like Cape Town — are the first to feel the bite as climate change really starts to take hold.

Are there parts of the United States that face similar challenges?

We’re already seeing this across the Southwest, from California to Texas. Record droughts have wracked the region in recent years, with some cities and farming communities pulled back from the brink only by timely but increasingly unpredictable monsoons and snowfalls. The cities fed by the Colorado River — from Los Angeles to Las Vegas to Phoenix — are in the danger zone because they are historically dry and likely to get drier. Colorado River reservoirs Lake Powell at Glen Canyon Dam and Lake Mead at the Hoover Dam, like their counterparts around Cape Town, are historically low and getting lower. Every year, folks in the desert Southwest hold their breath and wonder, “Is this going to be the year when we have to declare a shortage?” Many say it’s not a question of if but when.

How is American Rivers stepping up?

While the situation in the southwestern United States is dire, it’s not too late to take the steps necessary to avoid a Cape Town-like crisis. But it will take a new approach to managing water in the West. We need a better, more efficient, more enlightened way to make sure water gets to where it’s needed. We need to ensure that people use water wisely and are good stewards of a resource that’s coming into ever greater demand. And we need healthy, natural rivers — because they are the best infrastructure for gathering and delivering water for human use.

American Rivers is moving on multiple fronts to meet this challenge. We are working with stakeholders, including federal, state and local officials, water management agencies, irrigators and conservationists, on innovative water-sharing and trading schemes that would allow water to move more freely from place to place and user to user, depending on need and supply in any given year. We are promoting water efficiency as a more effective and economical alternative to dams, reservoirs, pipelines and pumps. And we’re spearheading projects to restore rivers, from California’s Central Valley to the headwaters of the Colorado River, to ensure that they are healthy and resilient in the face of climate change.

What is the next frontier of helping communities become more resilient to climate change?

People collect water from a spring in the Newlands suburb as fears over the city’s water crisis grow in Cape Town, South Africa, Jan. 25, 2018. | Image from Reuters

When Americans think of water scarcity, we tend to picture a dusty field or a cracked lake bed in some rural setting. The crisis in Cape Town brings home the impact water scarcity can have on urban dwellers. [Currently Capetonians are surviving on rations of 13 gallons per person of water per day. For comparison, the average American uses 80-100 gallons per day.]

The management of rivers and water resources in U.S. cities is often fragmented amongst multiple agencies with separate jurisdictions over source water, stormwater and wastewater. American Rivers is working in cities across the country to better integrate management of urban water in order to improve the ability of cities to ensure clean, plentiful water and — the other side of the climate coin — be better prepared for flooding. This work provides an opportunity to bring historically marginalized communities — those often least served by current water infrastructure and most vulnerable to pollution and flooding events — to the table when decisions are being made about how the city will manage its water.

At the end of our discussion, Chris added:

I hope that South Africa’s water-saving efforts work, that winter rains come this year and that Cape Town escapes the current crisis. But hoping for rain is not enough. Only by protecting and restoring our rivers and carefully stewarding our water can we meet the challenge of climate change, and ensure that no cities in the United States face their own Day Zero.