The following guest blog, a collection of boyhood memories from Mike Camp, is part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series on the Middle Fork of the Vermilion River in Illinois.

“A river poured through the landscape I knew as a child. It was the power of the place, gathering rain and snowmelt, surging through the valley, under sun, under ice, under the bellies of fish and the brown boats of sycamore leaves.” – Scott Russell Sanders

I was raised on a farm that bordered the Middle Fork of the Vermilion River, southeast of Collison, Illinois. In 1971, when I was sixteen, we moved to another farm, ten miles northwest near Armstrong, again on the river.

In sixty-four years, I’ve never lived more than two miles from the river’s banks. It has been my constant companion. The river, valley, and accompanying woods have always been my family and friend’s fascinating neighbor.

I had an almost Huck Finn boyhood— even as a kid, I knew I was lucky to be there.

However, even then I knew the river was not pristine. I knew there were problems, including people throwing trash into the river and occasionally soap bubbles on the edge of the eddies. But, the biggest problem was one we did not know about. There was coal ash being stored in the unlined pits on the floodplain. Chemicals from the coal ash were seeping into the groundwater and into the river. Floods were eroding the river bank near the coal ash pits, which could possibly lead to the worst-case scenario: a breach in the bank causing coal ash to flow directly into the river, wrecking the river for miles downstream. However, in the 1960s, I was as oblivious to this as anyone else and spent my time enjoying the river.

No one knows a landscape better than a curious child: hiking, crawling, climbing, swimming, poking with a stick, wandering and wondering. No hollow tree, seep spring, raspberry patch, river pool or riffle was left unexplored. Anytime school or farm work permitted my Mom heard these words as I raced out the door, “I’m goin’ to the river!”

Just upstream along the river from our house was a long, curving bend, with a wide, willow-edged sandbar. My older brothers, John and Bill, and a couple of their friends and I camped there every chance we got. My brothers were five and six years older and allowed me to tag along with considerable grace and only a little annoyance. We fished, using both poles and trotlines. For bait, we walked up the riffles, dragging a seine along the bottom. We caught hellgrammites, crayfish, minnows, and on one memorable occasion, a mudpuppy. The mudpuppy was so hideous looking that I thought that if they were twelve feet tall, they would rule the world.Gone Swimmin’

On the Collison farm, there was a deep pool, on a shady bend of the river, only a quarter mile from our farmstead. This is where my siblings and I learned how to swim. My older brothers had taught me to dog paddle, late in the summer when I was seven. With only a shaky remembrance of how to do it, we went swimming the next June for the first time that summer.

I did not realize then how much a river’s channels can change.

I walked confidently into the river in what had last year been waist deep water. This year it was a scoured-out hole deeper than my head. Down I went, then up splashing and swallowing water. Panicking, down I went again. Then up, trying to make a strangled yell to my brothers. The third time down, I decided I had better try to do something. So, flailing away I headed back toward the bank. By then they had figured out I was in trouble and came to help.

So, there I was lying on the sand, spitting water and gasping. First, they checked to see that I was okay. Then they immediately threatened to kill me if I told Mom. She was always worried about us going to the river, and this incident would have ended our fun. So, she never learned about it until years later.

Living Off the Land

When I could not be outdoors, I read all I could find about wildlife, Native Americans and living off the land. With my cousins, Carl and Bob, we’d catch and fillet some fish and attempt to cook them by impaling them on a willow switch or by laying them on a flat rock by the fire. The result would be a charred on the outside and raw on the inside morsel, usually with a dusting of fine sandbar sand. We gained enormous respect for anyone who could eat like that and survive.

One December day when I was twelve, my friend Joe and I gathered a bucket of mussels from the cold, clear water. Wanting to try to eat them, we took them up to the house and put them in Mom’s best soup pan. Fortunately, she was gone.

As the water boiled, the stench coming off the mussels was amazing. The shells fell open and we were both dreading having to try one. Fortunately, Mom came home. She voiced a pretty clear opinion of our experiment, and the mussels got tossed, untried. Another important lesson in living off the land: it required a lot more experience, knowledge and especially hunger to be successful.

The Float Experiment

The summer I was thirteen, my friend Denis and I decided to build a log raft to float the river. With a dull axe and determination, we chopped down some of the smaller soft maple trees that grew like weeds on the floodplain of the river. Carrying the logs to a sandbar, we tied it together with ropes braided out of baling twine, making it as tight and secure as we could. It was about 8 x 12 feet long, just big enough for two boys and a little gear.

With two long push poles, we launched and headed downstream, quickly learning that a raft is not the most nimble vessel. We ran it up onto a submerged rock, causing the back of the raft to swing downstream. The log I was standing on rotated, opening a gap, which my left leg fell down through.

So, there we were, going backward downstream, with my leg dragging and Denis hooting with laughter and me hollering at him. He quickly jumped off and pulled the raft up onto a sandbar, got me loose and we both laughed at the absurdity of it. We got back on and floated a-ways downstream. Then got into the water, towed the raft back upstream, and did it again several times.

Of course, when we built it, we did not think about the practicality of a raft— it works best going downstream, one-way. But that did not matter. The fun was in the creation and time on the water.

Rivers— the Cure for Boredom

Of course, this is only a fraction of the things I did on the river. As I said, even as a kid, I knew I was damn lucky. In a lifetime outdoors, with the river as my companion, I’ve never been bored because there is always something to see if you are open to it and looking.

My wife Kristin and I have felt so strongly about this that we have introduced our children, grandchildren and extended family to the river hoping they will gain an appreciation of the beauty, peace and excitement of being outdoors. Children today lead lives that are spent much more indoors than in the past. But if they have the opportunity to be exposed to nature, they may, like me, discover a lifelong, healthy pursuit of knowledge and pleasure.

Sadly, rivers need constant protection. We have a rare jewel in our midst. Good men and women fought against an unneeded pork-barrel dam in the in the 1970s and won. In the 1980s many of the same people won a National Scenic River designation for the stream. Now we need to work together to see that this coal ash problem is solved safely. Then, in the future, kids will be running out a screen door, yelling, “I’m goin’ to the river!”

Mike Camp is a long-time resident of Vermilion County, Illinois. Mike continues to be a champion for protecting the Middle Fork of the Vermilion River.

This guest blog by Dr. Donald Jackson is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series on the Big Sunflower River in Mississippi.

The rivers that course through the Mississippi River Alluvial Plain (a.k.a. “The Delta”) of Western Mississippi are integrated functionally as key components of floodplain river ecosystems. Such ecosystems, worldwide, are known for biological richness and typically support some of earth’s most productive inland fisheries. Very real and tangible dependencies exist between humans and these fisheries. The Big Sunflower River is a good example, and research into channel catfish growth in this Delta stream is providing important insights about this floodplain river system.

Rivers, unlike ponds and lakes, derive most of the energy driving biological productivity from organic material (primarily plant material) of terrestrial origin. Organic material, including leaves, woody debris and detritus from vegetation, is colonized by bacteria and fungi that convert it to forms usable (digestible) by aquatic invertebrates like insect larvae, snails and crayfish. Production of aquatic invertebrates is called secondary production. The amount of secondary production in an aquatic ecosystem is directly related to fishery production.

The more organic material entering the aquatic component of a river ecosystem, the greater the secondary production, and the greater the fishery production. Some organic material falls directly into a river’s channel (such as leaves falling from trees), but in floodplain systems like the Big Sunflower, flooding increases the area over which organic material is available for contributing to secondary production of aquatic invertebrates. During high water, rivers like the Big Sunflower fill their floodplains and fish leave the confines of the normal river channel. They follow the rising water both to exploit the additional sources of food the floodplain affords, and to spawn in the floodwaters. When the river recedes after high water, the fish return to the river’s channel nourished through feeding on the floodplain. Some species spawn on floodplains and return to the main channel having contributed a new year-class of juveniles to the river.

Generally speaking, fishery production for a given year in a floodplain river ecosystem is directly related to the height and duration of flooding one to two years before the year in question. This is usually the amount of time it takes for fish that were spawned in the flooded areas to grow large enough to be captured in the fishery (this is called recruitment into the fishery).

When a river’s cycles of flooding and low-flow periods are disrupted by human activities, the fishery and the people who may have dependencies on it can suffer. Although flooding can occur during any time of the year, across evolutionary time aquatic organisms have evolved to anticipate flooding during winter/early spring and low flows during summer/autumn. Leaves fall off of the trees in fall and are an energetic bank of high-quality organic material available for use by aquatic invertebrates once floodwaters inundate the associated floodplain. The invertebrates (primarily aquatic insects and crustaceans) maximize their growth during winter and subsequently become energetically efficient forage items for fishes that are also out on the floodplains. This is why, for example, channel catfish in rivers have their greatest growth during winter while channel catfish in ponds and lakes have their greatest growth during summer. Channel catfish are poikilothermic (cold blooded) so one would think that in both types of systems they would grow fastest during summer. But that just isn’t the case. It is a matter of availability of food for the fish. In river systems, the availability of food is greatest and more energetically efficient (larger food items) during winter (Flotemersch and Jackson 2003). The same patterns of foraging, growth, and recruitment to exploitable size exist for other riverine species.

Most rivers in “The Delta” have been modified by damming and dredging (including, in some cases, channelization). These activities are designed to minimize flooding. Two principal rivers in the region that have not been significantly altered are the Big Sunflower River and the Big Black River. In a Ph.D. study of growth rates for channel catfish in rivers throughout the state of Mississippi, these two rivers were, respectively, number one and number two for fastest growth (Shephard and Jackson 2006). Additionally, catch rates were highest in these two rivers (Shephard and Jackson 2009). The channel catfish has “cultural icon” status because recreational fishermen prize them and commercial fishermen target them for local markets. This fish species thrives in rivers that are allowed to function as floodplain ecosystems.

When people in Mississippi (and throughout much of America’s “Deep South”) think about fishing in lowland rivers, they are thinking primarily about catching catfish (Jackson 2016). The channel catfish is the “bread and butter” fish that sustains most fishing in these systems. Therefore, in order to safeguard the rich traditions and cultural values associated with our rivers, we should refrain from engineering these productive ecosystems in ways that modify their flow and flood regimes.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/4999/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”4″ center=”yes”]Take Action »[/su_button]

References:

Brown, Ralph B., John F. Toth, Jr., and Donald C. Jackson. 1996. Sociological aspects of river fisheries in the Delta Region of western Mississippi. Project Completion Report. Mississippi Department of Wildlife, Fisheries and Parks. Federal Aid Project F-108. Freshwater Fisheries Report number 154. 98 pp + 2 appendices.

Cloutman, Donald G. 1997. Biological and socio-economic assessment of stocking channel catfish in the Yalobusha River, Mississippi. Ph.D. Dissertation. Mississippi State University. 184 pp.

Jackson, Donald C. 2016. Deeper Currents. University Press of Mississippi. 231 pp.

Flotemersch, Joseph E. and Donald C. Jackson. 2003. Seasonal foraging by channel catfish on terrestrially burrowing crayfish in a floodplain-river ecosystem. Ecohydrology and Hydrology 3:61-70.

Shephard, Samuel and Donald C. Jackson. 2006. Difference in channel catfish growth among Mississippi stream basins. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 135(5):1224-1229.

Shephard, Samuel and Donald C. Jackson. 2009. Density-dependent growth of floodplain river channel catfish Ictalurus punctatus. Journal of Fish Biology 74:2409-2414.

Dr. Jackson is a former professor of fisheries at Mississippi State University. He is now the Sharp Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Fisheries at Mississippi State and the author of four books: Deeper Currents, Wilder Ways, Tracks, and Trails.

Last week, after four years of pressure to improve fish passage at Buckley and Mud Mountain dams on Washington’s White River from tribes, American Rivers, and others, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers hosted a groundbreaking ceremony for a new state-of-the-art fish passage facility.

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers hosted a groundbreaking ceremony for a new state-of-the-art fish passage facility.

On Friday afternoon under a drizzly yet glorious spring day, we joined individuals from the Army Corps, Puyallup Tribe of Indians, Muckleshoot Indian Tribe, Cascade Water Alliance, and Senator Patty Murray at a groundbreaking ceremony that kicked off the two-and-a-half-year project and eventual completion of the nation’s largest fish trap-and-haul facility.

Originating from the Winthrop, Emmons, and Fryingpan glaciers on Mt. Rainier, the White River travels 68 miles and drains almost 500 square miles before flowing into the Puyallup River and South Puget Sound. The White River is enjoyed by kayakers, fishermen, hikers, and visitors to Mt. Rainier National Park and the surrounding area. The river is home to four species of salmon (coho, chum, pink, and Endangered Species Act (ESA)-listed Chinook), as well as ESA-listed steelhead and bull trout. The river’s salmon and steelhead are central to the culture of the Muckleshoot and Puyallup Indian tribes.

Over $150 million in taxpayer funds are spent each year to restore salmon to rivers and streams around Puget Sound. This investment is undermined every year when thousands — even hundreds of thousands in some years — of salmon and steelhead die at the antiquated and dangerous Buckley Diversion Dam fish collection facilities, due to the poor condition of this dam and its undersized fish trap.

The Buckley fish trap was built in 1941 and from its inception, was never really sufficient to transport the large numbers of salmon attempting to return to their spawning grounds above Mud Mountain Dam. Even if salmon do make it into the overcrowded fish trap, they are often exhausted, delayed, impaled on rebar, and/or injured from the cramped holding facilities, which reduces their chances of survival and lowers their spawning capability after release.

To address the threat, American Rivers named the White River among America’s Most Endangered Rivers® in 2014, shining a national spotlight on the impacts of two Army Corps dams on salmon and steelhead runs and river health. Additionally, with the help of Earthjustice, we sued the Army Corps for “take” of a threatened species and failure to consult with NOAA Fisheries over dam operations. The legal action resulted in consultation and a plan by the Army Corps to avoid “take” and begin work on updated fish passage, which will help ensure the long-term survival of Puget Sound spring Chinook and other salmon and trout species in the basin.

The original facility was designed to move only 20,000 fish annually. During peak salmon migration, in odd years, the facility is overloaded, as it struggles to move upward of 20,000 fish per day. The new facility is designed to transport 60,000 fish a day, or upward of 1.2 million fish per year.

Last week’s commencement of the project to improve fish passage and upgrade the facility would not have happened without the dedication of the Muckleshoot Indian Tribe and the Puyallup Tribe. It also would not have happened without the leadership and commitment from Senator Patty Murray. Additionally, this project was made possible by the hard work of the Army Corps of Engineers – Seattle District along with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and NOAA Fisheries as wells as the Cascade Water Alliance.

We look forward to monitoring this project as it progresses toward a 2020 completion date and many thanks to all of our supporters who spoke up about Buckley Dam, which has killed thousands of salmon and steelhead in this endangered river. Because of your advocacy, the Army Corps is addressing the problems, which is great news for the White River, the threatened salmon and steelhead populations, and the overall health of Puget Sound.

Guest blog by Mike Davis of Minnesota Department of Natural Resources for our continued celebration of World Fish Migration Day.

Lake Pepin is a 23 mile long riverine lake in the Mississippi River created by the delta of its tributary, the Chippewa River of Wisconsin. Pepin is the widest place on the entire Mississippi River and at one time reached from the Chippewa to the city of St. Paul, MN and within about 10 miles of the foot of the rapids that extend upstream to St. Anthony Falls. By the 1800’s St. Anthony Falls had eroded upstream far enough to leave around 6 miles of prime spawning habitat for fish species dependent on rapids for spawning. The 60 mile run upstream to these rapids was an easy trip on a free flowing river for the fish of Lake Pepin and the river in between.

Residents around Lake Pepin in the 1800’s reported being awakened at night by the splashing of thousands of paddlefish feeding at the surface, probably targeting the enormous insect hatches common to the lake in summer. Commercial fishermen landed hundreds of sturgeon and paddlefish in seines. Huge spawning runs of blue suckers attracted settlers to the gorge to pitchfork and club them to feed to livestock and to pickle for later home consumption.

All that changed as industry set its sights on the river as a source of power and transportation. In 1917 a high dam was erected near the foot of the historic rapids that stopped the age-old migration of fish into the rapids. Pollution and lack of access to critical spawning habitat greatly reduced populations of these fish. Since the Clean Water Act of 1972, pollution has been greatly reduced and these fish populations have begun to increase. However the rapids spawning habitat that they need remains a missing link to their full recovery.

Today we have an historic opportunity to return rapids habitat to the Mississippi’s last remaining rapids that lies submersed below the reservoir of Lock and Dam 1. Locks have stopped serving the barge industry that they supported for decades and an Army Corps of Engineers Disposition Study is now underway to determine the fate of this dam and another upstream at St. Anthony Falls. Dam removal is a feasible option that could be the recommended outcome of this study. Removal of the dams would allow for restoration of the world-class St. Anthony Falls rapids and reopen the habitat lost a century ago. Sturgeon, Paddlefish, and other rapids dependent species could once again migrate and spawn in the midst of this major metropolitan area and in full view of its human residents.

As we continue to celebrate World Fish Migration Day we look to the new places where we could see rivers once again flowing free. World Fish Migration Day could, in a few years, become an annual celebration along the Mississippi’s resurrected rapids in downtown Minneapolis!

The following guest blog from Pam Richart with Eco-Justice Collaborative is part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series on the Middle Fork of the Vermilion River in Illinois.

The first major battle for the Middle Fork of the Vermilion River in its over 10,000-year history occurred in the early 1970s, when farmhouses were purchased and razed, and construction equipment moved in to dam the river for recreational purposes. Due to the hard work of tens of thousands of people who wrote letters, made calls, and met with their elected officials, the dam was stopped. Then in 1986, the Middle Fork of the Vermilion was designated a State Scenic River. Three years later, the U. S. Department of Interior designated 17.1 miles of the Middle Fork of the Vermilion as a National Scenic River. At the time, with a state-administered corridor management plan in place, people thought the river would be protected from future threats.

This year, as we celebrate the 50th Anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, the Middle Fork of the Vermilion is again under siege.

Deteriorated gabions and eroding riverbank next to the Old East Ash Pit on the Middle Fork of the Vermilion River, IL. Coal ash contaminants are seen actively seeping into the river. Taken May 2, 2018. | Pam Richart

This time, the river is threatened by a plan that could leave 3.3 million cubic yards of coal ash in its floodplain forever. The coal ash is stored in three unlined pits, just a few yards from the river channel. Two of the three pits are known to be leaking, and the erosion of the banks next to these impoundments continues to raise concerns over a possible breach and coal ash spill.

The Beauty and Wildlife of the Middle Fork

East-central Illinois boasts some of the richest farmland in the country. However, the predictable “flat-as-a-pancake” topography abruptly changes when approaching the Middle Fork of the Vermilion River from the west. This scenic river carves a meandering path through Illinois’ Grand Prairie glacial deposits, exposing scenic, steep, valley slopes with towering bluffs. Most of the area along the Middle Fork is forested (including stately oaks, beech, and sugar maple), but there are also several prairie sites and seep springs. Giant sycamore trees with their twisted, exposed roots line the riverbanks providing shade during summer months, and the variety of hardwood species in upland and bottomland forests present a firestorm of fall color. The only structures visible from the river are the abandoned power plant and its smokestack and pump house located further downstream.

The scenic river designation begins at the northern boundary of the Middle Fork State Fish & Wildlife Area and extends through Kennekuk County Park, power plant property, and on through Kickapoo State Park. The river and its 1,000-foot wide scenic corridor pass through nearly 10,000 acres of public lands. The only private property is the land owned by Dynegy, where the Vermilion Power Generating Station and associated coal ash pits are located.

The Middle Fork is an upper perennial stream, which is uncommon in central Illinois. The average gradient is 2.9 feet per mile and it twists and turns through boulder riffles, making it fun to paddle. This clear, gravel-bottomed river is one of the highest quality and most biologically diverse in Illinois. Numerous species of fish, mussels, and other invertebrates live in its fast-moving water, sand and gravel raceways, and clear pools. Good populations of game fish such as smallmouth bass, crappie and channel catfish are present. Perhaps the most notable among the abundant and diverse fish fauna is the bluebreast darter. The breeding male has a colorful olive-green body with a bright blue breast, orange dorsal fins, and red spots along the sides. The only known location of this species in Illinois is in the Vermillion River basin.

River otter and her babies on the Middle Fork of the Vermilion River, IL. | Nature Photography by David Hale

Wildlife is abundant. Woodlands provide habitats for many mammals, including the grey fox, fox squirrel, raccoon, and white-tailed deer. The least shrew, red fox and striped skunk make their home in the transitional grassland/shrub areas. River otter, mink, beaver, and muskrat inhabit river shorelines. Wood ducks, egrets, heron, kingfisher, and shorebirds make their home in the bottomlands. The upland wooded areas are frequented by warblers, vireos, and most common songbirds, and it is not uncommon to see a pileated woodpecker. Several pairs of nesting bald eagles have made their home along the river’s edge, and the elusive southeastern shrew also is found in the area.

In spring, the woods explode with a vibrant display of colorful wildflowers, including Jack-in-the-pulpits, violets, bluebells, sweet Williams, spring beauties, Dutchman’s-breeches, wake-robins, and nodding trilliums.

Vermilion History and Economy

A 1,000-year-old, native American complex listed on the National Register of Historic Places sits along the bluffs and in the floodplain of the Middle Fork on the east side of the river, in Kennekuk County Park. This is a ceremonial site that is believed to have connections to the Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site, a 2,000-acre complex of mounds where a pre-Columbian city thrived at the confluence of the Missouri and Mississippi rivers. Named after the Collins family that farmed the area, the complex features eight mounds that exhibit lunar alignment. The most prominent – Indian Springs Mound – is about 7 feet tall, sits on a bluff overlooking the river, and was built over a wooden, burned funeral structure that contains the remains of indigenous leaders. What connects Collins to Cahokia are the mounds themselves, their shape and placement, and the artifacts found there.

The river system also provides the benefits of a strong recreation economy to Vermilion County. Kickapoo State Park, Kennekuk County Park, and the Middle Fork State Fish and Wildlife Area are key destinations for local residents and visitors, enjoyed for canoeing, kayaking, tubing, wildlife viewing, photography, hunting, angling, hiking, and horseback riding. A livery located in Kickapoo State Park puts over 10,000 people on the Middle Fork River in canoes, kayaks and tubes each year.

We Need to Come Together to Protect This River Again

Later this year, the Illinois EPA is likely to decide on a proposal by Vistra Energy/Dynegy (Dynegy) that could leave 3.3 million cubic yards of coal ash in unlined, leaking pits on the banks of the Middle Fork, where erosion from this natural meandering river threatens their long-term stability.

Two of the three coal ash pits are known to be leaching arsenic, barium, boron, chromium, iron, lead, manganese, molybdenum, nickel, and sulfate into the river. These contaminants are known to cause birth defects, cancer and neurological damage in humans, and can harm and kill wildlife, especially fish.

But perhaps most alarming is the ongoing erosion of riverbanks next to the two oldest pits. Gabions (wire baskets filled with rock) installed in the 1980’s to protect the pits from the meandering river have been severely compromised, leaving the river bank vulnerable to aggressive erosion. They have been ripped off the banks by the Middle Fork, and either lie in the channel next to the pits or have been swept downstream. Two storms in 2015 were responsible for eroding banks precariously close to the New East Ash Pit, causing Dynegy to seek emergency riverbank stabilization to avoid a potential breach.

A recent engineering study by Dynegy’s consultant shows just 15 feet remains between the river bank and the toe of the slope of the coal ash pits in some areas along the North and Old East pits. A previous study indicated that the Old East and North Ash Pits could fail if separation between the bank and the toe of the slope of these pits is reduced to just eight and 10 feet, respectively. In the meantime, a near-record storm this past February appears to have further eroded the banks adjacent to these pits – severely undercutting banks and leaving large, cavernous holes from downed trees and boulders moved downstream by this flood event. As the Middle Fork of the Vermilion River continues to wear away at the sides of riverbanks next to these pits, the threat of a catastrophic breach continues to increase. And while Dynegy’s plan includes bank stabilization, we know no stabilization lasts forever.

This is another time the public needs to demand the protection of Illinois’ only National Scenic River. There or no requirements for a public hearing on a proposal that could leave Vermilion County residents a legacy of toxic coal ash and, to date, the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency has declined to hold one. Any decision that is made by the Illinois EPA as to whether or not Dynegy will be able to cap and leave its coal ash in the river’s floodplain with bank stabilization will be made without any public input.

That’s why Eco-Justice Collaborative is holding a People’s Hearing in Danville, Illinois, next month. The agency’s decision will either positively – or negatively – affect the health, recreational, scenic and economic values of this National Scenic River. This hearing will give those who rely on the river an opportunity to voice concerns that are backed up with facts by experts who will testify on the risks of leaving the ash in the river’s floodplain.

Take Action Today!

That is the only solution that can fully protect this National Scenic River from ongoing pollution or a potential coal ash spill.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/4946/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”4″ center=”yes”]Take Action »[/su_button]

Pam is Co-Director of Eco-Justice Collaborative (EJC). EJC is organizing a grassroots campaign to remove the coal ash from the Middle Fork of the Vermilion River.

Guest blog by Hackensack Riverkeeper Outreach Coordinator, Caitlin Doran.

The saying “a picture is worth a thousand words” has become a little worn these days. At Hackensack Riverkeeper, we prefer, “a pictures is worth a thousand pounds of trash.”

The 2017 National River Cleanup Photo Contest winner! Anton Getz removed crates from shores of the Hackensack River, NJ.

The winning National River Cleanup® photo contest picture was just one moment that was part of many great river cleanups. The 2017 photo captures how hard working and dedicated volunteers are to cleaning up local waterways. American Rivers continues to support this idea with National River Cleanup, an initiative that provides much needed support to our organization and others like it.

In a given river cleanup season, dedicated volunteers like Anton Getz remove upwards of 15 tons of trash and debris from our 210 square mile watershed. They do this in extreme cold, heat, and sometimes-rainy weather, working in places as far north as Lake DeForest in Rockland County, NY, all the way down to the Newark Bay from the peninsula of Bayonne, NJ. Hackensack Riverkeeper volunteers are the boots on the ground (literally), cleaning up our most important natural resources – like the Meadowlands, the kidneys of our river and one of the most important estuarine environments on the East Coast, and the reservoirs that provide us with our drinking water.

This particular river cleanup took place at Woodcliff Lake Reservoir in Woodcliff Lake, NJ – part of the drinking water system for close to 1 million people. Volunteers are always surprised to find such a litany of litter threatening their drinking water supply, and these cleanups continue to open our eyes to the way non-point litter reaches even the most sensitive parts of our watershed. Thanks to volunteers like Anton, we are getting ahead of the trash in many parts of our watershed, as we work to be the upstream solution to river and marine pollution!

With the help of National River Cleanup we were able to get the word out about our cleanup and have trash bags to supply volunteers with. Every season we are able to organize cleanups and register them through their site alongside other cleanups going on around the country. After submitting cleanup photos for the National River Cleanup photo contest we were ecstatic to hear that our photo had made it to the voting round and even more excited when we were announced as the winners.

This spring, we’ll be returning to Woodcliff Lake Reservoir to undo more environmental damage. Join us! If you live in New Jersey and would like to know more about the work of Hackensack Riverkeeper, please call 201-968-0808 or email Caitlin at Outreach@hackensackriverkeeper.org. See you at the river!

What if you couldn’t pay your water bill? What if the city cut access to water in your home, and throughout your neighborhood?

In Detroit in 2014, more than 33,000 homes lost access to water service because residents couldn’t afford the costs. The problem is ongoing. Just two months ago, the Detroit Free Press reported that more than 17,000 people in the city are at risk of shut-offs.

In Flint, Michigan, even at the height of the crisis when their drinking water was contaminated with lead, residents paid some of the highest water rates in America.

“If you care about clean water, you need to care about affordability,” says Katie Rousseau, Director of Clean Water Supply in the Great Lakes for American Rivers.

“This is a human rights issue. When you don’t have clean water, what do you do for drinking, bathing, cleaning and cooking? When you can’t pay your water bills, that has all kinds of consequences. People can lose their homes, their children.”

“Everyone deserves clean, safe, affordable water,” Rousseau says.

That is why American Rivers is sponsoring “Making Ends Meet: A Workshop on Water Affordability” in Philadelphia, May 30-31. We’re teaming up with the Mayors Innovation Project, the Water Center at Penn, and the Clean Water for All coalition to offer this free workshop to share solutions on how cities can keep water, sewer and stormwater services affordable for all residents. The workshop will feature Michael Nutter, former mayor of Philadelphia, and other experts.

“We need to get ahead of this problem. It shouldn’t take a crisis to force cities and states to protect people’s health. We are committed to ensuring clean water and healthy rivers for all,” says Rousseau.

Learn more and register for “Making Ends Meet: A Workshop on Water Affordability”

When it comes to recovering federally endangered pallid sturgeon in the lower Yellowstone River, a strong majority of Montanans support removing an existing diversion dam that has been implicated in their demise.

That’s according to a new poll that was commissioned by American Rivers and its conservation partners and conducted by Tulchin Research last month. The pollster interviewed 400 likely Montana voters and has a margin of error of +/- 4.9 percent.

Among the key findings of the poll:

- 81% of Montanans support efforts to protect the pallid sturgeon, a prehistoric fish that was added to the endangered species list in 1990

- By a 64-21 margin, Montanans support removing the Intake Diversion Dam to recover pallid sturgeon and replacing its function with irrigation pumps to meet the needs of farmers

- By a 51-26 margin, Montanans support removing the Intake Diversion Dam even after being told the cost to do so could be three times higher than the cost of building a new dam and bypass channel

- By a 62-20 margin, Montanans would be more likely to support an elected leader who supports removing Intake Diversion Dam to recover pallid sturgeon

The poll comes at a pivotal time, as a federal appeals court recently lifted an injunction that was blocking the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers from building a new $59 million concrete dam just above the existing Intake Diversion Dam. The sole purpose of the proposed new dam is to divert water from the river into a canal that irrigates 54,000 acres of cropland in the Lower Yellowstone Project.

As part of the project, the Corps wants to build a two-mile-long bypass channel that it hopes pallid sturgeon and other fish will use to get around the dam. But most fisheries scientists who have studied this issue are skeptical the bypass channel will work. They point to the fact that no artificially constructed bypass channel has successfully passed any sturgeon species anywhere in the world.

Since Intake Diversion Dam and five other upstream diversion dams were constructed on the lower Yellowstone River early in the 20th century, the pallid sturgeon population has dwindled because they can no longer access historic spawning habitat.

To successfully reproduce, pallid sturgeon need long stretches of free-flowing river so their hatched embryos can drift downstream and gradually mature into juvenile fish. Currently, the hatched embryos drift downstream into Lake Sakakawea, an artificial reservoir on the Missouri River, where they perish due to a lack of dissolved oxygen in the water. Removing Intake Diversion Dam would give pallid sturgeon access to 165 miles of historic habitat.

Biologists estimate there are only 125 adult pallid sturgeon left in the lower Yellowstone River and the adjacent Missouri River below Fort Peck Dam. Government scientists have long said that the key to their recovery is removing impassable barriers such as Intake Dam that prevent them from accessing their historic spawning areas.

American Rivers hopes the Corps will hold off on building the new dam and bypass channel and instead work with conservation groups and Montana’s congressional delegation to explore other options for delivering water to the Lower Yellowstone Project so Intake Dam can be removed. One promising option currently under consideration is piping water from Fort Peck Reservoir into the Lower Yellowstone Project.

“We need to keep the lake fish away from the river fish.”

This outdated idea was the reason the Roaring River dam was completed in 1976 by the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency (TWRA) to limit “rough fish” from moving upstream from a large reservoir in the Roaring River watershed. Biologists do not propose rough fish barriers anymore, and biologists at the TWRA like Mark Thurman are working now to remove these structures that block rivers.

The Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency with support from the Tennessee Aquatic Connectivity Team identified this dam removal as an excellent opportunity to restore the Roaring River, a Tennessee state scenic river, because the dam was in disrepair, blocked passage for aquatic species, and was a public safety hazard for those who love to recreate in and along this beautiful river. The dam was removed in August 2017 and to date is the largest river restoration dam removal in Tennessee.

Like most dam removals, there were challenges to overcome in the process. A surprising challenge was handling the significant public interest in the project. Community members were concerned about what the river would look like after the dam was removed, so TWRA met this need for information with press releases and public notices. The removal drummed up excitement in nearby communities and locals even brought lawn chairs to watch the show. The project managers met with local press and talked about the benefits and goals of the project which helped the community embrace a river that better supports safe recreation and allows aquatic communities to thrive now that the Roaring River dam is gone.

The removal of this outdated structure connects 250 miles of main stem and tributary river miles up and downstream of this project. This popular paddling stretch no longer requires a portage and fish and other aquatic species have improved passage. Species such as white bass, redhorse, and the Eastern hellbender are expected to benefit by reconnecting populations above and below the dam.

American Rivers congratulates all the partners that made this project a success including the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, The Nature Conservancy, Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Tennessee Technical University, Southeast Aquatic Resources Partnership, and others who participate in the Tennessee Aquatic Connectivity Team. Thanks to your hard work the Roaring River flows freely for the benefit of people and nature.

Want to read about another project like this one? Check out the Citico Creek dam removal project blog here.

Late last year, the U.S. Senate appropriations committee proposed a legislative “rider” that would have required the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to “immediately” initiate construction of the environmentally devastating Yazoo Pumps. A huge outpouring of opposition prevented the legislative “rider” from becoming law, but it was only pulled from the bill at the very last minute. The very real risk of future attempts to resurrect this project catapulted Mississippi’s Big Sunflower River to the top of the list of America’s Most Endangered Rivers® of 2018.

The $300 million Yazoo Pumps would drain and damage 200,000 acres of ecologically rich waterfowl habitat in the Mississippi Delta so large landowners can increase agricultural production on marginal lands that have always flooded. This project is so damaging it was vetoed by the George W. Bush Administration in 2008 under the authority of the Clean Water Act. That veto was intended to permanently stop the project.

A Project from Another Era

The Yazoo Pumps are a hold-over from another era. Originally authorized by Congress in 1941, the Yazoo Pumps would be one of the world’s largest hydraulic pumping plants. The Pumps would be located in one of the most sparsely populated regions in the state of Mississippi. When turned on, the Pumps would move up to six million gallons of water per minute from one side of an Army Corps-built flood control structure to the other side of that structure.

These massive pumps will not protect communities from floods. Instead, they will drain wetlands so that a small number of large landowners can intensify agricultural production on lands that regularly flood.

Astonishing Damage

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and an independent hydrologic review found that the project would drain and damage up to 200,000 acres of ecologically significant wetlands—an area larger than all five boroughs of New York City. The Army Corps acknowledged that 67,000 acres of wetlands would be harmed, but the agency admitted that it did not evaluate the full range of wetland impacts.

The wetlands that would be drained provide some of the richest stopover habitat in the country for migratory birds, including waterfowl that live out much of their lives far beyond the borders of Mississippi. More than 450 species of fish and wildlife, including 257 species of birds—and 20 percent of the nation’s duck populations—rely on the wetlands that would be drained by the Yazoo Pumps.

The wetlands that would be drained also support vast numbers of other wildlife, including the Louisiana black bear—the inspiration for the “Teddy Bear”.

During a 1902 hunting trip in the Yazoo Pumps project area, President Teddy Roosevelt refused to shoot a black bear that had been captured and tied to a tree. The story of a President who refused to carry out such an ignoble act was memorialized in political cartoons that ran in papers across the country. Those cartoons in turn lead to the creation of a stuffed bear named Teddy.

While the Teddy Bear thrived, the Louisiana black bears did not. They were wiped out along with millions of acres of bottomland hardwood wetlands that supported them. However, protection of the Yazoo Pumps area wetlands gave the Louisiana black bear vital habitat that it needed to recover and thrive. In 2015, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service announced that the federally-threatened Louisiana black bear had met its recovery goals and no longer needed the protections of the Endangered Species Act.

The EPA Veto

The environmental harm that would be caused by the Yazoo Pumps led the George W. Bush Administration to veto the project under the rarely used Clean Water Act Section 404(c) veto authority.

This authority lets the EPA put a stop to projects that will cause an, “unacceptable adverse effect on municipal water supplies, shellfish beds and fishery areas (including spawning and breeding areas), wildlife, or recreational areas.” EPA has always reserved the veto for only the most environmentally egregious actions. The Yazoo Pumps definitely meets that standard.

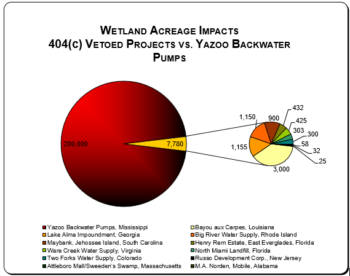

The 200,000 acres of wetland impacts that would be caused by the Yazoo Pumps are 25 times the combined wetland impacts of all previously vetoed projects. Even the “smaller” level of 67,000 acres of impacts acknowledged by the Army Corps are 8.6 times the combined wetland impacts of all previously vetoed projects.

After fully vetting the project’s environmental impacts and carefully considering tens of thousands of public comments, EPA put a stop to the Yazoo Pumps in 2008 by issuing the 12th Clean Water Act veto in the history of the Clean Water Act. EPA based its veto on the Army Corps’ assessment of 67,000 acres of harm.

EPA determined that the Yazoo Pumps would cause “unacceptable damage” to, “some of the richest wetland and aquatic resources in the nation,” including a highly productive floodplain fishery, substantial tracts of highly productive bottomland hardwood forests, and important migratory bird foraging grounds.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service concurred with these findings, and highlighted its concerns that the project would drain wetlands that provide critical wildlife habitat in the Panther Swamp National Wildlife Refuge, the Yazoo National Wildlife Refuge, and the Delta National Forest.

The public overwhelmingly agreed with the decision to veto the Yazoo Pumps. Of the 48,000 comments submitted by members of the public, 99.9 percent supported the veto, including 90 percent of the comments from Mississippians and more than 540 independent scientists.

Mississippi’s largest newspaper, the Clarion Ledger, wrote five editorials opposing the Yazoo Pumps. The New York Times wrote six editorials lampooning it.

A Multi-Million Dollar Handout to a Few

The unacceptable harm from this project cannot be balanced against any meaningful benefit. Only a small number of large farms, averaging 1,000 acres each, would be able to benefit from the ability to intensify agricultural production. Given the project’s enormous price tag, this translates into a multi-million dollar handout to these landowners, many of whom already receive substantial farm subsidy payments. Not surprisingly, an independent economic analysis demonstrates that the Yazoo Pumps will, at best, return only pennies on the dollar.

Congress Should Respect the Veto Process and Listen to the Public

While there are many complex environmental decisions facing the nation, whether or not to construct the Yazoo Pumps is not one of them. As acknowledged by Senator John McCain in 2004, the Yazoo Pumps are, “one of the worst projects ever conceived by Congress.”

Congress should respect the robust and comprehensive process that led to the Clean Water Act veto, and the overwhelming public support for that veto, and reject all efforts to resurrect the Yazoo Pumps.

This guest blog by Melissa Samet, Senior Water Resources Counsel, National Wildlife Federation, is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series on the BIG SUNFLOWER RIVER.

Last summer, the Chetco Bar fire in Southwest Oregon burned over 170,000 acres of our U.S. National Forest in Southwest Oregon, close to the town of Brookings and the California border in the Wild and Scenic Chetco River watershed. There is now a push to log and remove burned trees from the watershed. How we decide to act in the Chetco could set a precedent nationally – impacting our clean drinking water supplies, salmon and steelhead habitat, and recreation opportunities for generations to come.

Fire has always been a natural part of the landscape in the forests across our region, but we are now in a new era of “megafires.” On our National Forests, a century of forest fire suppression, the push to grow high densities of trees in large plantation-like mono-cultures, and especially, changing climatic conditions have led to drier and hotter weather patterns and created more combustible conditions. The larger and hotter forest fires that result can have significant impacts on forest health, rivers, water quality, and local communities.

The science on the effects of logging on the fragile post-fire landscape clearly shows dramatic increases in the amount and duration of harmful sediment in streams and rivers compared to watersheds that are left alone to recover. Some simple rules can help reduce harm to water quality and salmon habitat. This includes staying away from streamside areas and staying off of steep slopes prone to soil erosion and landslides that once triggered can dump too much sediment into streams over an extended period of years. It is vitally important to avoid creating new roads and decommission any temporary roads that are often the largest contributor to harmful amounts of stream sediment.

So, what will happen in the Chetco? This watershed is home to abundant salmon and steelhead runs, supplies drinking water to 14,000 residents in Brookings, and supports outstanding upland and instream recreation. There’s a lot at stake.

The U.S. Forest Service is now considering alternatives and taking public comment on a draft proposal to cut trees burned by the fire that could generate more than 70 million board feet of timber – double what the Rogue River-Siskiyou National Forest sold all of last year.

To their credit, thus far the Forest Service is considering staying out of high-value areas and using sensible management practices in their proposed action. Unfortunately, some extreme voices are calling for controversial and unsustainable levels of clearcutting that would sacrifice clean water and other public values. As in the past, this approach would likely only lead to more conflict and litigation, and if implemented, affect extensive damage to soils, water, and fish and wildlife habitat.

As we craft responses to the Chetco Bar fire and future wildfires that will inevitably occur in the region, we must do our utmost to protect the most valuable natural resources that come from our forests: the clean water, rivers and wild salmon that we all want to preserve for generations to come.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/5315/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”4″ center=”yes”]Take Action »[/su_button]

Over the past decade, there has been a growing movement across the United States to remove dams that no longer serve their intended purposes. While history might indicate otherwise—the U.S. led the world in dam building over the last century—agencies, tribes, individuals, and a myriad of other river stakeholders are realizing that of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ catalogued 90,000 dams blocking rivers and streams, many are considered ‘deadbeat dams.’ These dams that were once at the epicenter of a community’s livelihood are now old, unsafe, or simply outdated. More importantly, these dams also have a negative impact on the local environment and economy, by depleting fisheries, degrading river ecosystems, and otherwise altering recreational industry and the jobs it supports.

The entire removal process, from the initial concept or idea to the actual implementation, can take decades. For instance, in Washington State, the physical removal of the Elwha and Glines Canyon dams on the Olympic Peninsula’s Elwha River took less than three years to complete in 2014, but the actual planning process began in 1992, after Congress passed the Elwha River Ecosystem and Fisheries Restoration Act authorizing the removal of the dam in order to restore the altered ecosystem.

But what prompted Congress to take action?

The Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, who for centuries lived off the salmon that ran up the river every spring, summer and fall, had been opponents of the dams since they were first constructed in early 1900s. And there were many organizations, including American Rivers, who were advocating for their removal during the 1980s.

But long before dam removal was on the radar of Congress or any conservation organizations, Dick Goin, a Port Angeles, Washington pulp mill worker and master fisherman, began fishing the Elwha in 1937. Dick’s family lived primarily on Elwha salmon, and he felt the salmon saved his family, and that he owed a debt both to the fish and the river. He began a decades-long personal fight to remove the two dams and allow wild salmon access to the Elwha, as a wild river.

This understated story of Goin’s persistence for removal of the dams was captured by in the film The Memory of Fish, produced by Jennifer Galvin. Last fall, American Rivers, along with Galvin, toured the film across the Pacific Northwest, with the goal of inspiring communities near rivers at risk to engage in political action and citizen science.

“Touring The Memory of Fish with American Rivers was an incredible experience,” said Galvin from her home in New York. “At the beginning of each screening I’d look out into the audience knowing that some people came because they had something to say about dams; some were there because they had something to say about ‘environmentalism’ in the Trump era; some were there because they love fishing; and some were there because they knew Dick Goin.”

“What always moved me the most was that the movie moved them, helped people feel something for a river and for fish,” she said. “It’s not easy to see your audience cry, but it does open a new door of dialogue and understanding, especially across heated political divides. Showing an environmental documentary that is a deeply emotional story helps people understand what American Rivers is working so hard to do. The hope is that the tour moved people beyond being simply aware of river issues, like dam removal, to actually doing something about it.”

The film is now available for download, purchase, and streaming on Amazon Video, iTunes, Google Play and on DVD. Additionally, the film is available for any organization or person to host a screening, as a springboard for discussion, inspiration, and action. Galvin hopes Goin’s legacy will leave a similar impact on audiences as it left on Galvin.

“I wake up every morning these days thinking that the world needs more lifelong citizen scientists like Dick Goin,” said Galvin. “The stakes are getting higher for us when it comes to healthy rivers, and an active citizenry requires repetitive, focused, persistent work. This kind of work isn’t sexy and usually goes unseen. This was the genius of Dick Goin’s fight to free the Elwha – he was persistent, he was observant, and he was never afraid to use his voice. I know that one story like The Memory of Fish can change the story for many other rivers. Dick Goin’s legacy lives on through this film, but it’s up to us to make it count – for the Elwha River and so many other rivers at risk.”

For more information on purchasing, streaming, or hosting a screening of The Memory of Fish, visit: thememoryoffish.com.