The following guest blog from Brian Hanson is part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series on the Middle Fork of the Vermilion River in Illinois.

I am writing in response to an article about the Middle Fork of the Vermilion River published in the Chicago Tribune on April 10, 2018. The river has been selected as one of America’s Most Endangered Rivers®.

I broke into tears when I read it.

I confess to being a bit emotional recently. I’ve been told that it’s a common problem with people who have had death or near-death events and develop a heightened sense of what is or has been important in their life. I had my own near-death experience two months ago and now wear a portable defibrillator.

Seeing the Vermilion River in the paper brought back a favorite memory of my dad, H. Gordon Hanson, a great guy who died way too young. I had high hopes for more quality bonding time with him after he took early retirement from his job. His job? He was a biologist for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. In the early days of his career, it seemed like his job was to try and make the pillage of our environment “look pretty.” But then, the word “environment” became more important. He gave me his copy of “Silent Spring”, the anti-pesticide book by Rachel Carson, to read shortly after it came out. Eventually, his job title was changed from just “Biologist” to “Chief of Environmental Resources Division” for the Army Corps.

For those of you who enjoy fishing for Coho salmon in Lake Michigan, my dad deserves more than a tip of the hat. He was involved in many projects like that during his career with the Army Corps.

He was also largely responsible for the development of recreational areas on Army Corps property along the upper Mississippi. Many campgrounds on Army Corps property there and throughout the Midwest were due to his efforts. If you’ve camped at any of them you can thank my dad.

While I was a student at the University of Illinois in Champaign, Dad came down to spend a little time with me. He suggested that we take – what appeared on the map to be – a reasonably short float down the Vermilion River. He had our clunky old aluminum canoe strapped to the top of the car. The Vermilion was not known as a float stream back in those days, and we soon found out why. It took all of our strength on umpteen occasions to lift that canoe over massive logjams and downed trees. We arrived at our takeout point well after dark. Dad had to hitch a ride (in the dark) to go back and get our car.

Of all my memories of time spent with my dad, that “gentle” float trip down the Vermilion River has been a favorite. Part of his legacy that I cherish is that he had a big part in rivers like the Vermilion becoming National Scenic Rivers. I wonder if I was an unknowing member of his scouting mission that day.

Polluters like Dynegy and others have tried to tarnish my father’s legacy in Illinois and where I live in Michigan. Lake Michigan continues to be threatened with horrific environmental damage if and when Line 5 bursts beneath the Straits of Mackinac.

Our current leadership – or lack thereof – in Washington and in state capitals across the country tell us they want to roll back regulations that protect valuable resources like the Middle Fork Vermilion River.

I have good reason to be crying.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/4946/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”4″ center=”yes”]Take Action »[/su_button]

Editor’s Note: A more recent article has been published on this issue in the Chicago Tribune. Check it out!

Brian Hanson is an advocate for healthy rivers in Illinois.

This guest blog was written by the Board of Directors of the United Tribes of Bristol Bay. It is a part of our blog series on America’s Most Endangered Rivers® Rivers of Bristol Bay.

Salmon season is just beginning in Bristol Bay, Alaska. Lots of things are happening this time of year. First, the air fills with the sound of swallows. Then, kings start swimming into our rivers. The first catch is celebrated. Nets are set, and smokehouses fill with strips. This is the way spring has turned to summer each year for generations. But the proposed Pebble Mine threatens that sacred life cycle which we hold dear.

The people of Southwest Alaska have thrived on the clean waters, abundant wildlife, pristine lands and the strong cultural traditions of our region since time immemorial. Our people have a resilient, respectful, and peaceful way of life, grounded in the earth’s provisions and dedicated to honoring our ancestors.

The Pebble Mine threatens more than just our land and waters, and it is more than a disruption of our daily, seasonal and annual activities, our abundant wildlife, and our strong salmon runs. The proposed Pebble Mine is a threat to our livelihood, our people, our culture and our way of life. Our ancestors have not just survived, but thrived, as a unified people for thousands of years because of the natural bounty the earth provides. Developing this mine would go against all that our culture celebrates and relies upon.

For generations, the Dena’ina, Yup’ik, and Alutiiq people of Bristol Bay taught their children to honor the land for what it provides and to hold sacred the water for all it sustains. Our connection to the land and water is what makes us who we are as a people. Salmon, moose, caribou, seals, geese and other wildlife not only provide sustenance, but also ground us in our culture, in a seasonal way-of-life. The natural world is intertwined in our story-telling, dance, clothing, spirituality and all of the other traditions that we teach to our younger generations.

Pebble Mine will not only negatively affect salmon for human consumption, it will affect wildlife’s consumption as well. | Patrick Moody

The executives at the Pebble Partnership claim there will not be harmful impacts to fish, that our culture will not be disrupted, that mining and clean water can co-exist, but we know better. They’ve already proven themselves wrong, mistreating the land in exploration activities and attempting to buy local support.

Nearly twenty years ago, when this project came to light, our elders warned us of the harm that the Pebble Mine would bring. They knew that the mine would bring irreversible impacts: polluted waters, disruption of our hunting and fishing grounds, and a loss of culture as we lose these key components of who we are. Extensive scientific research has since proven what we already knew to be true: Pebble is the wrong mine in the wrong place.

The people of Bristol Bay have stood together to protect our region from Pebble, and we will never back down. We will not give up our livelihoods for the profits of a foreign mining company. Clean water is the lifeblood of our people. It runs like veins throughout our region, sustaining every facet of our lives. In Bristol Bay, we have a resource more precious than gold, and we will not stop fighting to protect it.

Sign-on by June 27th to be included in our petition!

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/5000/petition/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”4″ center=”yes”]Take Action »[/su_button]

Author: United Tribes of Bristol Bay Board of Directors

Author: United Tribes of Bristol Bay Board of Directors

United Tribes of Bristol Bay (UTBB) is the first tribally chartered consortium in the Bristol Bay region of Southwest Alaska. UTBB’s mission is to protect the lands and waters that support the traditional way of life of the indigenous people of Bristol Bay by advocating against unsustainable large-scale hard rock mines like the Pebble Project.

This month, the Arizona House of Representatives’ Committee on Energy, Environment, and Natural Resources is holding a series of special meetings – one in Kingman (June 13th), one in Camp Verde (June 15th), and one in Buckeye (June 20th). The goal of these meetings is to give legislators a chance to learn about constituents’ concerns regarding water supplies and to investigate potential solutions to the water issues facing our state.

Representative Rusty Bowers and Senator Gail Griffin will chair the meetings, and other legislators will also attend. Of particular interest will be a discussion about the Lower Basin States of Arizona, California, and Nevada, and their diligent efforts working on a Drought Contingency Plan (DCP) to stave off shortages in the Colorado River, which Mexico has also joined. It is critical that Arizona Department of Water Resources be authorized by the Legislature to sign Arizona on to the DCP, and to speak as “the one voice” for Arizona’s Colorado River users.

All citizens wishing to make their views known are encouraged to attend, fill out a speaker slip and present their views.

This is a great opportunity to tell your state officials directly your opinions about Arizona’s rivers and sustainable supply of clean, safe, and reliable drinking water. We hope you can join!

- Kingman

- When:Wednesday, June 13th at 2pm (detailed agenda)

- Where: Mohave County Administration Building (700 W Beale St, Kingman, AZ 86401)

- Camp Verde

- When:Friday, June 15th at 10am (agenda)

- Where: Cliff Castle Casino Hotel Conference Center (555 W Middle Verde Rd, Camp Verde, AZ 86322)

- Buckeye

- When:Wednesday, June 20th at 10am (agenda)

- Where: Palo Verde Nuclear Education Center (Palo Verde Nuclear Education Center (600 N Airport Rd, Buckeye, AZ 85326)

For several years, an array of Colorado River Upper Basin stakeholders, including state agencies, farmers and ranchers, conservationists and municipal water managers have been partnering on innovative water conservation pilot projects to help ensure healthy flows and habitat in the river, maintain levels in Lake Powell and protect our vibrant agricultural communities.

Additional support is needed, though, to turn those pilot projects into a sustained, effective demand management and system conservation program that includes a water bank in Lake Powell to store the conserved water. Expanded funding for these projects will help implement market-based solutions on a larger scale to maintain healthy flows in the Colorado River and sustain the jobs, wildlie and communities that depend on it. Additionally, states will need to enact water policies and procedures that allow water conserved through these projects to be left in the river and allowed to reach Lake Powell.

In Episode 11 of We Are Rivers, we explore the ideas and efforts behind expanded demand management and increased conservation across the Upper Basin with Scott Yates of Trout Unlimited and Taylor Hawes of The Nature Conservancy, both of whom are deeply integrated into the nuance and detail of developing a system that works for everyone who relies on the Colorado River, as well as the long-term, sustainable health of the Colorado River itself.

Listen to We Are Rivers Episode 11: How Water Management and Flexibility Can Save the Colorado River today!

Rocky Point is coming back to life. Local residents of Choppee, South Carolina and the surrounding area remember a vibrant past at Rocky Point. A popular hangout for locals, Rocky Point once provided a great gathering place for Fourth of July picnics, afternoons jumping into the Black River from a rope swing on the bluff, sunning on the river’s small sandy beaches, and launching boats for a day on the to fish or paddle on the river or on Choppee Creek. By the end of the summer, locals will once again be able to experience these activities at the new Rocky Point Community Forest.

After five long years, Rocky Point is nearly ready to reopen to the public. The valuable piece of river frontage and forest was secured for conservation as a Community Forest. Thanks to Winyah Rivers Foundation, Georgetown County Parks and Recreation, The Nature Conservancy, and the Open Space Institute and the generous support of the North American Wetland Conservation Act program of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the South Carolina Conservation Bank, the Duke Water Resources Fund, the Carolina Bird Club, and the Butler Conservation Fund, Rocky Point Community Forest provides and protects 650+ acres and 1.8 miles of river and creek front for passive recreation and education.

When it was purchased, Rocky Point joined a network of over 12,000+ acres of protected land throughout the Black River Watershed. Since it holds a South Carolina Department of Natural Resources Scenic River designation, there is a focus on the conservation of the natural and cultural character of the Black River corridor. In line with this mission, the forests of Rocky Point will be restored and managed sustainably and the wetlands and wildlife will be protected.

Rocky Point Community Forest will provide opportunities for recreation, education, restoration and conservation. At the beginning of the summer, construction began for a paved boat ramp, kayak launch, primitive parking and picnic. A simple trail network will be expanded upon as the project continues to mature. Community members will be able to enjoy the area as they did once before. The first of its kind in the area, the community forest will serve as an outdoor classroom for forestry students, land owners and the general public to further their understanding of the sustainable forestry methods used on site. Restoration of a 200 year old cemetery enhanced the cultural resources of the land in addition to the surrounding forest. Restoration of the forest to longleaf pine where appropriate will help manage and maintain the ecological integrity of the forest. Conserving these lands will protect both the regional ecosystem integrity as well as the services the forests, wetlands and river provide to the public.

The future of the Rocky Point Community Forest is bright with opportunity. Providing a public place for community members to connect with the Black River and the forest is important to preservation of our natural resources. Soon Rocky Point will be alive once more.

Author: Emma Boyer, Winyah Rivers Foundation

Emma joined Winyah Rivers as the Waccamaw Riverkeeper in 2015, leading the organization’s education and advocacy efforts until May 2017 when she stepped down as a result of growing her family. At that time, Emma took on a part-time role with Winyah Rivers to advance our organization’s involvement in the acquisition of the Rocky Point property on the Black River and the Singleton property on the Waccamaw River. Emma continues as Winyah Rivers part-time Land Officer. Emma has a Master’s Degree in Environmental Science and Policy and a Bachelor’s Degree in Biology.

The Chattooga River may be famous for its rapids, and being the site for the filming of Deliverance, but it’s now being celebrated for its status as a United States Wild & Scenic River. The Chattooga takes its name from “Tsa-tu-gi,” an old Cherokee village on the river. The word has no other meaning in Cherokee, and whatever it once meant in Creek has long since been forgotten. What has not been forgotten is the tremendous effort that was taken to designate 57 miles of the river, and 15,432 acres of its surrounding land, as federally-protected river corridor under the Wild & Scenic Rivers Act.

Claude Terry (rear) & Jimmy Carter (front) on the first open-canoe descent of the Chattooga’s Double-Drop of Blue Sluice rapid. Jimmy Carter, then-governor of Georgia, was instrumental in the designation of the Chattooga as a federally-protected Wild & Scenic River in 1974. | Credit: Doug Woodward / American Rivers

On May 10th, 1974 the Chattooga River was designated Wild & Scenic by Congress. Flowing through North Carolina, Georgia and South Carolina, the Chattooga is recognized as one of the Southeast’s premier whitewater rivers. It begins in mountainous North Carolina as small rivulets, nourished by springs and abundant rainfall. High on the slopes of the Appalachian Mountains near Whiteside Mountain is the start of a long journey that ends at Lake Tugaloo between South Carolina and Georgia, dropping almost 1/2-mile in elevation along the way.

Flowing through three national forests, the river is one of the few remaining free-flowing streams in the Southeast. It offers outstanding scenery, ranging from thundering falls and twisting rock-choked channels to narrow, cliff-enclosed deep pools. Dense forests and undeveloped shorelines characterize the primitive nature of the area.

The Wild & Scenic Rivers Act, the federal legislation that protects rivers deemed to preserve certain rivers with outstanding natural, cultural, and recreational values, was passed in October of 1968. The Act is notable for safeguarding the special character of now over 200 of these rivers, while also recognizing the potential for their appropriate use and development. It encourages river management that crosses political boundaries and promotes public participation in developing goals for river protection.

With 2018 being the 50th anniversary of the Act, land managers, conservation groups, paddlers and other river enthusiasts nation-wide have been celebrating the Act’s impact by visiting and paddling these places and sharing information on the success of this historic and unique form of protection.

Risa Shimoda (River Management Society), Don Kinser (past president of American Whitewater), Regina Goldkuhl & Gray Jernigan (MountainTrue) are all smiles shortly after putting-on the Chattooga at Earls Ford. | Credit: Jack Henderson

As just one of many events, River Management Society organized a celebratory paddle/rafting trip for local and regional river conservation organizations’ staff and members, as well as other river enthusiasts, to gather and further grow the conversation surrounding southeastern river conservation.

American Rivers joined staff and members of River Management Society, American Whitewater, United States Forest Service, Sumter National Forest, South Carolina Department of Natural Resources, MountainTrue, City of Hendersonville, NC and City of Columbia, SC for a paddle trip on Section 3 of the Chattooga River. There were 12 rafters and 7 kayakers. The plethora of organizations present laid host to wonderful conversations on river conservation work, paddling adventures, Wild & Scenic River planning, and a contagious feeling of inspiration across water enthusiasts towards the good work being done to protect and advocate for our nation’s waterways.

Pictured front-left to rear-right: Mark Singleton (American Whitewater), Scott Harder (South Carolina DNR), Melissa Martinez (US Forest Service – Wild & Scenic River Program), Jack Henderson (American Rivers & River Management Society), Regina Goldkuhl (MountainTrue), Risa Shimoda (River Management Society), May & James Leinhart, Kevin Colburn (American Whitewater), Plenio Beres (Sumter National Forest), Gray Jernigan (MountainTrue), Mike Huffman (City of Hendersonville NC), Charles Pellet (South Carolina DNR).

Not pictured: Erin McCombs & Gerrit Jobsis (American Rivers), Andy Grizzel & Karen Kustafik (City of Columbia SC), Don Kinser (American Whitewater), Bob Marshall (South Carolina DNR)

When this trip was first being planned, early in the year, the organizers were worried about the water being too low, however strong spring rains brought the free-flowing Chattooga to a relatively high level and ended up providing the group’s trip with plenty of flow. While many of the kayakers opted to depart the river midway down at Sandy Ford, prior to entering the rivers’ tougher obstacles, the daring rafters and their skilled guides continued downstream into the classics of Section 3 including rapids named ‘Narrows,’ ‘Second Ledge,’ ‘Eye of the Needle,’ ‘Painted Rock,’ and ‘Bull Sluice.’

Trip participants enjoyed conversations with their fellow river conservation companions and colleagues. Some folks had known each other across organizations and agencies for several years, collaborating on conservation work, while other attendees had the chance to meet long-time heroes. New relationships were formed, and the river offered a friendly and open environment to converse on regional water conservation, protection and recreation work, and informally learn about one-another’s work. Bringing together staff from three of nation’s leading river-conservation and management groups – River Management Society, American Rivers and American Whitewater, as well as several state and local groups, was a unique experience of which the impact-of would not be soon forgotten.

Wildwater Rafting Outfitters, in Long Creek South Carolina, hosted the entire group, and guided the trip’s commercial rafters down the river. The Chattooga River is where it all began for Wildwater; they were the first commercial outfitter to run the river in 1971 and have ever-since held a reputation for safety, responsibility, skill and advocacy towards paddle travel on many sections of the Chattooga River. Our guides handled the high water with skill and tact, and provided the guests with a wonderful experience.

The author enjoys some ‘down-time’ on Soc-Em-Dog rapid on Section 4 of the Chattooga. | Credit: Matt Jackson

With this year being the 50th Anniversary of the Wild & Scenic Rivers Act, American Rivers encourages everyone to explore, and advocate for, wild and scenic rivers of all kinds. Check out www.rivers.gov/wsr50/ to learn about Wild & Scenic Rivers in your area, and how to get involved with them!

Other links:

The Wild President: https://vimeo.com/213281194

https://www.rivers.gov/rivers/chattooga.php

https://www.5000miles.org/share-your-story/

Like many American families, road trips were a big part of my upbringing. Every summer, my parents would pack up our red Chevy Blazer and we’d hop in the car in pursuit of our next big adventure. Regardless of our destination and the time it took to arrive, my brother and I would always play the license plate game, each determined to beat the other in finding all 26 letters of the alphabet exclusively on license plates. Not only did the game fuel our competitive spirits, it also helped pass what seemed like days to get to our destination.

While I haven’t played the license plate game in quite a few years, I can’t help but check out the different plates when I’m on the road. Who knew there were so many different plates available. It wasn’t until I was much older that I learned many of these designs actually raise money and build awareness about important issues to state residents.

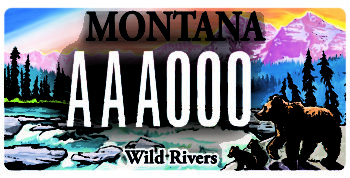

Here in Colorado, and just north of us in Montana, rivers are making a statement on license plates.

In Colorado, American Rivers partnered with Colorado Trout Unlimited, Audubon and the Colorado Watershed Assembly to build support for rivers across the state. In Montana, American Rivers worked with Bozeman artist Rachel Pohl to depict the North Fork of the Flathead River, one of Montana’s four Wild & Scenic Rivers, on their license plate.

In Colorado, American Rivers partnered with Colorado Trout Unlimited, Audubon and the Colorado Watershed Assembly to build support for rivers across the state. In Montana, American Rivers worked with Bozeman artist Rachel Pohl to depict the North Fork of the Flathead River, one of Montana’s four Wild & Scenic Rivers, on their license plate.

If you’re a resident of Colorado or Montana, show your support for rivers by purchasing and proudly displaying a river-themed license plate on your vehicle! All money raised goes toward the conservation, protection and restoration of rivers and streams in Colorado and Montana respectively. So whether you’re a farmer, kayaker, hunter, rafter or angler – or just someone who appreciates the natural beauty that rivers bring to our landscape – these license plate shows your willingness to put your money where your interest lies!

Purchase a Colorado Protect Our Rivers license plate here (to donate to American Rivers, put our name in the “Partner Code” box) and read up on a few Frequently Asked Questions.

Purchase a Montana Wild Rivers license plate here (scroll to the second line to find American Rivers’ plate).

Purchase a Montana Wild Rivers license plate here (scroll to the second line to find American Rivers’ plate).

Who knows, maybe I’ll bring back the license plate game this summer. One thing I do know, I’ll be on the lookout for more river themed license plates!

The following guest blog by Clark Bullard is part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series on the Middle Fork of the Vermilion River in Illinois.

What? One of America’s National Scenic Rivers is on this year’s top 10 list of America’s Most Endangered Rivers®? That’s not supposed to happen.

The Middle Fork of the Vermilion River is an oasis of natural beauty and ecosystem health in the middle of North America’s Great Corn and Bean Desert. Thirty years after being rescued from the dam builders, this treasured river ecosystem is now threatened by three million cubic yards of coal ash, dumped 40 feet deep adjacent to the riverbank behind a long-abandoned power plant. The dump is owned by Dynegy, which emerged from bankruptcy a few years ago and prefers the “cap and run” approach to shedding its responsibility for the arsenic and other toxins that are oozing orange leachate out of their unlined ash dumps.

The Middle Fork of the Vermilion River is an oasis of natural beauty and ecosystem health in the middle of North America’s Great Corn and Bean Desert. Thirty years after being rescued from the dam builders, this treasured river ecosystem is now threatened by three million cubic yards of coal ash, dumped 40 feet deep adjacent to the riverbank behind a long-abandoned power plant. The dump is owned by Dynegy, which emerged from bankruptcy a few years ago and prefers the “cap and run” approach to shedding its responsibility for the arsenic and other toxins that are oozing orange leachate out of their unlined ash dumps.

The lesson here is simple: laws and regulations alone do not protect rivers, people do.

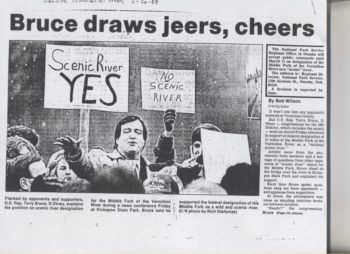

In the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, a massive 22-year nonpartisan all volunteer grassroots campaign was waged to stop a dam project that would have flooded the Middle Fork valley; this fight ultimately led to the Middle Fork of the Vermilion’s National Scenic River designation. For the first 10 years, 10,000 acres of land were bought while the project inched forward, construction appropriations were defeated, and studies were conducted. Then in 1976, 60,000 petition signatures were collected the old-fashioned way, representing every county in the state. A bipartisan collection of state legislators who received 10,000 handwritten letters from their constituents believed that facts mattered, and were impressed by facts about one of Illinois’ best aquatic ecosystems. The dam project was stopped.

Environmental victories are always temporary, but losses are permanent. The Middle Fork is no exception. A dozen years after the dam project was defeated, the Middle Fork of the Vermilion River was designated as a state scenic river, and the Illinois state legislature directed the Governor to apply for National Scenic River status to ensure that the river remained free-flowing.

The National Park Service’s endorsement of the National Scenic River designation was the strongest to date on the river’s “outstandingly remarkable values” in all 6 categories: scenic, recreational, geologic, fish and wildlife, historic and archaeological. However, die-hard reservoir proponents lobbied President Ronald Reagan’s lame duck Interior Department Secretary, who rejected the National Park Service’s recommendation and denied Illinois’ request. Again, the statewide citizens group wasted no time persuading the state’s bipartisan congressional delegation to co-sign a letter to be carried by the Republican Governor to President Bush’s newly-appointed Interior Department Secretary. It worked. Since 1989, the Middle Fork of the Vermilion River has been safe from dam projects, but remains vulnerable to other risks.

The National Park Service’s endorsement of the National Scenic River designation was the strongest to date on the river’s “outstandingly remarkable values” in all 6 categories: scenic, recreational, geologic, fish and wildlife, historic and archaeological. However, die-hard reservoir proponents lobbied President Ronald Reagan’s lame duck Interior Department Secretary, who rejected the National Park Service’s recommendation and denied Illinois’ request. Again, the statewide citizens group wasted no time persuading the state’s bipartisan congressional delegation to co-sign a letter to be carried by the Republican Governor to President Bush’s newly-appointed Interior Department Secretary. It worked. Since 1989, the Middle Fork of the Vermilion River has been safe from dam projects, but remains vulnerable to other risks.

Now, 55 years’ worth of toxic coal ash remain where they were dumped on the river bank – an ugly but localized scar along a 17-mile stretch of otherwise public land. Rivers own their floodplains, so it is only a matter of time before a catastrophic failure of the ‘ash dam’ carries toxins an unpredictable distance downriver, harming people and wildlife along the way.

Dynegy needs to stop polluting the Middle Fork with their coal ash and take responsibility for the waste they’ve dumped next to the river. Future generations of taxpayers shouldn’t have to cover for Dynegy’s negligence.

Dynegy is being sued for violating the Clean Water Act by Prairie Rivers Network, which was formed in the late 1960s to stop dam projects throughout the Midwest, including this one. As that generation of founders and activists passes the baton to a new generation, we take this opportunity to express our gratitude again to the staff of American Rivers, who provided inspiration and valuable advice during our campaign to secure the National Scenic River designation 30 years ago. We can only hope that the next generation of activists remembers the words of David Brower: “This generation will decide if something untrammeled and free remains, as testimony that we had love for those who follow.”

TAKE ACTION TODAY!

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/4946/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”4″ center=”yes”]Take Action »[/su_button]

Clark Bullard was one of the first board members of the coalition that became Prairie Rivers Network.

This piece originally appeared in the 2018 Spring Issue of Outside Bozeman.

Here on the northern edge of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, we sit perched on the headwaters of the continent. The mighty Missouri, Green, Yellowstone, and Snake river systems all originate within this landscape, and while the headwaters of these great rivers all flow from a highly-protected block of public land, only one of the four—the Snake River headwaters—is protected under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act.

This year, on October 2, 2018, the Act will turn 50. A number of local streams are eligible for designation under the Act, and a lot of people in southwest Montana are working to make that happen. But before we can celebrate the Act’s future, we need to understand its past.

The Genesis

President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act into law in 1968, but the effort that ultimately got us there started much earlier—and right here in Bozeman. The 1950s and 1960s were the zenith of the big dam-building era in our country, and a number of proposed dams drew the attention of Montanans, including the Spruce Park dam on the Middle Fork of the Flathead River, in what is now the Great Bear Wilderness.

This dam, which would have been built by the Army Corps of Engineers, was to be a mirror of the Hungry Horse Dam one drainage south on the South Fork of the Flathead River. It would have backed up the Middle Fork some 11 miles, and was just one of nearly a half-dozen such dams proposed for the upper Flathead River system.

The Spruce Park proposal caught the attention of John and Frank Craighead, well-known wildlife biologists and conservationists, who might be best known for their pioneering work on grizzly bears in Greater Yellowstone. The Craighead brothers led the fight against the Spruce Park dam, and in 1957, John Craighead first proposed the idea of a federally protected system of “wild rivers” at a conference at Montana State University.

John and Frank would go on to publicize the need to protect wild rivers; a decade later, they were at the forefront of getting the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act passed, along with Interior Secretary Stewart Udall and senators Frank Church (D-Idaho), Gaylord Nelson (D-Wisconsin), Lee Metcalf (D-Montana), and Rep. John Saylor (R-Pennsylvania).

The Craighead family’s ties to Montana remain strong. Lance Craighead, executive director of the Craighead Institute in Bozeman, reflects that even though the brothers tend to be more well-known for their work as wildlife biologists, “my father Frank and uncle John always considered the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act to be one of the greatest conservation achievements that they contributed to in their lifetimes.”

Lance recalls that the two brothers’ river ethic started while canoeing the Potomac River, when they witnessed the degradation of rivers in the East. This awareness and concern grew during their many raft trips down wild rivers in the West after World War II. As with many modern-day river runners and anglers who fall in love with the waters they ply, these experiences turned into a desire to protect those rivers. “As kids, we grew up floating wild rivers with Dad and Uncle John,” recalls Lance. “Thanks to the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, countless generations of other kids are able to do the same.”

The Wild and Scenic Rivers Act Today

Montana currently ranks seventh in the nation with a total of 368 Wild and Scenic river miles, about the same as New Jersey and Pennsylvania. We have four designated rivers: the Upper Missouri River through the Breaks, and the North, Middle, and South Forks of the Flathead River. This amounts to about 0.2% of the 177,000 river miles in Montana. According to the National Inventory of Dams, which is maintained by the Army Corps of Engineers, Montana currently has 2,960 dams. Montana hasn’t had a new Wild and Scenic River designated since 1976. Meanwhile, our neighbors in Wyoming, Idaho, and Utah added a combined 900 miles of new Wild and Scenic rivers in 2009 alone. Clearly, the balance between conservation and development intended by Congress when it passed the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act 50 years ago has not yet been struck.

There are, however, a growing number of people in Montana working to change that. In December 2017, the bipartisan East Rosebud Wild and Scenic Act (S.501) passed the U.S. Senate by unanimous consent, and was introduced in the House. The East Rosebud bill would protect 20 miles of the stream as it flows through public land off the Beartooth Plateau, and has been championed by the broad-based local coalition known as the Friends of East Rosebud Creek, which includes virtually every rancher, business owner, and resident in the area.

In addition to East Rosebud Creek being on the cusp of becoming Montana’s next Wild and Scenic River, the state-based coalition, Montanans for Healthy Rivers, currently has over 1,000 Montana businesses and over 2,000 citizens endorsing its proposal to designate 50 new Wild and Scenic streams on public lands in the Crown of the Continent and Greater Yellowstone ecosystems.

In 2014 and 2016, bipartisan statewide polls on river issues in Montana found that three-quarters of Montanans support the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, and two-thirds of Montanans support designating more Wild and Scenic rivers in the state. Furthermore, 85% of Montanans think that “rivers are highly important to our economy and way of life,” and nearly nine out of ten voters would like to see the number of protected rivers in Montana maintained or increased. Support for protecting Montana’s wild rivers is overwhelming, regardless of ideology, party affiliation, gender, age, or geographic region.

Montana’s business community is taking note of rivers, as well. Business for Montana’s Outdoors (BMO) conducted a survey that polled 200 businesses from every county in Montana, to find out opinions and perspectives on the connections between our outdoors, outdoor way of life, and the economy. Nearly three-quarters of business owners said that we can protect land and water and have a strong economy at the same time, and 70% claimed that the “Montana outdoor lifestyle” was a key factor in deciding to locate or expand their business in Montana.

“Montanans and Montana businesses are clearly connected to their environment, whether we’re talking about an outdoor recreation business, a manufacturer, a marketer, or someone in the tech industry,” explains BMO’s Marne Hayes. “People are in Montana for our landscapes and waterways, for the value that those things bring to them personally, and for how they contribute to the culture of their business.”

Then there is the science behind the roles that wild rivers play for humans, fish, and wildlife in our changing and developing world. In many arid regions of the West, the writing is on the wall, and tough choices must be made—and made soon. Scott Bosse of American Rivers in Bozeman explains the urgency: “Given how climate change is rapidly shrinking our snowpack and the West is one of the fastest-growing regions of the country, I think we’re going to see a lot more dams and other water development projects proposed in Montana over the coming decades. That’s why we need to act now to protect our highest-value free-flowing rivers. It will be too late if we wait any longer.”

What does this mean for local rivers, you might ask? While Montana is sure to receive more riverside development in the future, and likely more dams as well, favorite streams like the Gallatin, upper Yellowstone, upper Madison, and Smith rivers all have local groups pushing for their protection. Kristin Gardner from the Gallatin River Task Force in Big Sky sums up the reason behind this interest: “Because of the Gallatin River, we not only live here, we thrive here—as individuals and as a community… Wild and Scenic protection would ensure that the necessary recognition and planning is in place to secure the long-term health of these irreplaceable resources for generations to come.”

“People are passionate about their local streams,” adds Charles Drimal of the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, which is working with Montanans for Healthy Rivers. “In communities like Livingston, Gardiner, Bozeman, and Big Sky, where rivers are just as much a cultural identity as a hydrological force, people want to see iconic rivers like the Yellowstone and Gallatin protected.”

The Future of Wild Rivers

Public lands and rivers, along with our nation’s system of national parks and preserves, have been called “our best idea.” In southwest Montana, we are fortunate enough to live this every day. But not everyone in this country is quite so fortunate. So, how do we maintain support nationwide for this “best” idea?

One way is to keep wild rivers relevant through stories. River stories are one of the most treasured cultural traditions in the outdoor world. Whether you’re spinning a yarn about that time you failed to properly tie down the raft and had to chase it downstream; when Grandpa almost landed a fish this big; when Liz swam the Kitchen Sink in April without spilling her beer; or when a bear loved the smell of frying bacon in the river kitchen a little too much—one and all, these river stories capture and spread the wildness that protected rivers help to maintain in our lives.

In celebration of the 50th Anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, the national nonprofits American Rivers and American Whitewater have teamed up with a number of outdoor gear companies to create 5,000 Miles of Wild. Their goal is to collect 5,000 wild-river stories and to protect 5,000 more miles of such rivers nationwide.

For many of us, what we love about protecting certain wild rivers is legacy. “The legacy of river protection under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act will serve not only everyone today who cherishes our remaining natural rivers, but all the generations to come in an era when the values of our free-flowing streams will become increasingly evident,” says river author Tim Palmer. This is not to say that it will be easy. Our public lands and rivers are under attack, and it’s going to take a lot more people getting involved to protect them—outdoor recreationists, homeowners, farmers and ranchers, and businesses from every sector. We Americans are learning that conservation is difficult, and protection is not necessarily permanent, unless we all stand up for our wild lands and rivers. Wild rivers, fortunately, are one thing that almost all of us love and understand to be important and necessary. To put it simply, says Lance Craighead: “We need more of them.”

What will that require, you might ask? In John Craighead’s words from 2013, “It doesn’t require much more than having Congress understand how important those rivers are to all Americans. They’re about American as American can be.”

Floods are a natural part of life on a river. But scientists say that severe floods will happen more often as climate change worsens – compounded by the paving over of wetlands and building in floodplains.

After any flood subsides, our natural reaction is to want to rebuild as soon as possible. Everyone wants to help communities get back on their feet and rebuild quickly. But in a world where disastrous storms happen more and more frequently, it’s just as important to make sure that communities are rebuilt better and smarter, so they will be safer and more resilient in the face of the next deluge.

How do we do that? First, we make certain we’re rebuilding in the right places. Floodplains and wetlands often receive the brunt of the impact from storms and floods because that’s exactly how they are supposed to work. Properly managed, they provide buffers that can protect lives and property from the impacts of floods, often more effectively and much more economically than artificial barriers like dams and levees. A single wetland acre, saturated to a depth of one foot, retains 330,000 gallons of water — enough to flood thirteen average-sized homes thigh deep.

When we alter and build in floodplains, we compromise these natural defenses and put lives, homes and businesses in harm’s way. Wherever possible, flood-damaged communities should consider how they can preserve these natural defenses to provide dependable flood protection and avoid risk to property.

Second, we must ensure that we are rebuilding in the right way. Individuals can take advantage of state and federal programs for buyouts and relocations to build their new homes on higher and safer ground. Some communities, such as Valmeyer, Illinois and Charlotte-Mecklenburg, North Carolina decided to move entire portions of their towns to higher ground following repeated flooding.

Unfortunately, President Trump rescinded a critical rule that required rebuilding federal infrastructure to higher standards following floods. Despite the administration’s failure, communities should develop and enforce zoning and building codes that ensure new structures are sited and constructed to be flood-resilient.

Third, we must reject outdated flood control approaches. In the past, many cities and towns reacted to floods by building dams, levees and floodwalls, channelizing rivers in concrete straitjackets – an approach that actually increases flood damage downstream. Billions have been spent on dams, levees and other flood control structures, but we have been largely unsuccessful in “controlling” anything. Flood damages have continued to increase nationwide, costing taxpayers, families, businesses and the environment.

We now know that often the best way to reduce flood damage, and to safeguard people and property, is by avoiding development in floodplains, re-connecting rivers with their floodplains and by protecting and restoring wetlands. After decades of sustaining major flood damage, Vermont now actively promotes these natural flood-management solutions, as opposed to building more and bigger dams, levees and floodwalls. Recent projects in California’s Central Valley prove that reconnecting rivers to floodplains has multiple benefits for flood protection, water supply, fish and wildlife habitat and recreation.

These lessons apply to communities coast to coast, big and small, urban and rural. Our elected officials at the local, state and federal levels should place new emphasis on the restoration of natural flood protection as the most cost-effective way of safeguarding lives and property.

Congress is currently considering a Water Resources Development Act to improve the Army Corps of Engineers. Our elected leaders should require the Army Corps to fully consider natural infrastructure approaches when developing flood risk reduction projects. We know how to keep communities safe. Will Congress act?

This guest blog is by Melissa Diemand, Sr. Director of Communications at Potomac Conservancy.

The Potomac River, the source of drinking water for over 5 million residents in the Washington, DC area, earned its highest health grade ever in Potomac Conservancy’s 10th State of the Nation’s River report. The Potomac’s health has improved to a B, up from a B- in 2016 and all the way up from a D in 2011.

Top pollutants – nutrients and sediment – are on the decline, more streamside lands are under protection, and native fish and wildlife are returning. The Potomac now supports healthy communities of striped bass and white perch, and it is one of the few rivers along the U.S. East Coast where American shad populations are thriving.

“The Potomac River is making a comeback and is on its way to joining the Charles, Willamette and other urban rivers that have made remarkable recoveries in recent years,” said Potomac Conservancy President Hedrick Belin.

It’s a dramatic turnaround for the river that President Lyndon Johnson once declared, a “national disgrace.” Since the passage of the Clean Water Act in 1972, changes in agricultural practices, upgrades to wastewater treatment plants, and reductions in industrial discharges have significantly lowered water pollution. And in recent decades, the EPA’s Chesapeake Bay Program has led a historic federal-state cleanup effort to reduce water pollution to the Bay and its tributaries, including the Potomac River.

Federal leadership, while certainly critical, cannot alone address the myriad of threats to our waters; it takes a village. Potomac Conservancy is proud to work alongside American Rivers and conservation partners across the Chesapeake Bay region who are preserving healthy lands and clean water.

Our work is more important now than ever. The report warns that polluted urban runoff, rapid deforestation, and new attacks on federal water protections could derail progress.

Learn more about the Potomac River’s recovery and emerging threats at www.potomacreportcard.org.

About Potomac Conservancy

Potomac Conservancy is a nonprofit organization that is working to ensure the Potomac River boasts clean water, healthy lands, and vibrant communities. The Conservancy improves water quality through land conservation and advocacy, and empowers a local movement to take action for clean water. Potomac Conservancy is recognized as one of Washington, DC’s best nonprofits by the Catalogue for Philanthropy and is accredited by The Land Trust Accreditation Commission. Learn more at www.potomac.org.

Bogle Vineyards Takes a River-Friendly Approach to Winemaking

In California, water is more precious than sunshine. The state has experienced years of crippling drought. Thankfully, an increasing number of vintners are making strides to reduce the amount of water they use to grow grapes and operate their winemaking facilities.

Take Bogle Vineyards. A decade ago, the company decided to get certified as a sustainable winery through the LODI/California Rules for Sustainable Winegrowing program. The certification requires that winegrowers meet strict standards for managing pests naturally, powering their equipment efficiently, improving soil quality and using water responsibly. In celebration of summer adventures and Bogle Vineyards’ commitment to environmental sustainability, the winery has made a donation to support American Rivers’ mission to protect the rivers that provide clean water, recreation and a connection to the great outdoors.

“In our hearts, we are farmers,” says Jody Bogle, one of the three siblings who operate the 50-year-old family business, now one of the largest wineries in the United States. Jody and her siblings, Ryan and Warren, grew up in the Sacramento Delta — an expansive tidal marshland at the confluence of California’s two largest rivers, the San Joaquin and Sacramento. The Delta’s quilt of islands, which are separated by narrow creeks called sloughs, is one of the most productive agricultural zones in the country. For six generations, the Bogle family has worked this land, growing corn, wheat and, beginning in 1968, wine grapes.

“We know that clean, abundant water is what keeps our land fertile and alive,” Jody says. “We believe we have a responsibility to keep it that way for our kids and grandkids.”

In addition to making sure they irrigate their 1,900 acres only during dry weather cycles, the Bogles also installed a high-efficiency drip irrigation. They also use low-water nozzles and recapture the water when spraying down tanks. Plus, they recycle 95 percent of the winery’s solid waste and have introduced falcons, hawks and owls to keep pests in check.

At first, the Bogles didn’t think their customers would care that they were implementing sustainability techniques. But the response was overwhelmingly positive.

“It turned out our customers care as much as we do about how we use natural resources,” Ryan Bogle adds. “We have received incredible feedback from people who loved the fact that they could get a good wine at a good price — and not have to sacrifice their environmental ethics. They want to support us because they believe we’re doing the right thing.”

Winemaking team of Dana Stemmler, Chris Smith and Eric Aafedt along with Ryan Bogle, Jody Bogle and Warren Bogle.

The family didn’t stop there: Bogle Vineyards has become a leader in the effort to influence California’s wine industry toward more Earth-sensitive practices. Bogle, which purchases grapes from vineyards across California, asks its growing partners to pursue sustainable certification, paying a bonus to farmers who grow and harvest grapes in an environmentally responsible way. As a result, 92 percent of grapes crushed during Bogle’s 2017 vintage are certified-sustainable.

“American Rivers is proud to partner with Bogle Vineyards, a company that demonstrates a significant commitment to environmental sustainability — and that has a deep connection to keeping our rivers healthy and our water clean for generations to come,” says Bob Irvin, President and CEO of American Rivers.

Learn more about rivers and how you can protect them by visiting www.AmericanRivers.org/greateroutdoors.