While the national discourse is focused on issues that divide us as a country, clean water is one of the values that should unite us. No matter who you are or where you are from, we all need clean, safe water for drinking, for growing the food we eat, and for nurturing a healthy environment. Just like the veins and arteries in our bodies, rivers and streams are the circulatory system of our country. Rivers truly are essential for all life.

Where I live in Virginia, the Potomac River provides my drinking water for roughly 6 million people in the region. On weekends I see grandparents fishing with their grandkids on the riverbank. The trails along the river are perfect for a stroll with friends, especially as the fall colors are popping. And from downtown DC all the way upstream, the river is alive with people kayaking, canoeing, and having fun in the water.

Science shows that time on and near water improves our mental health. And as our RIVERS AS ECONOMIC ENGINES report demonstrated, a healthy river drives real opportunities for jobs and businesses.

But my home river and rivers across our country looked a lot different 50 years ago. Before the safeguards of the Clean Water Act were in place, the Potomac River smelled so bad, you’d often have to hold your breath when walking by. Every time I played in or around the river, I would get skin infections. Other rivers from Maine’s Androscoggin to Ohio’s Cuyahoga were so polluted they caught fire. Across the country, rivers were treated as sewers – they were health hazards, unfit to support life.

The Clean Water Act, passed with bipartisan support, was a historic milestone establishing a fundamental right to clean water. It remains one of our nation’s most vital safeguards for the health and safety of our communities and our environment.

One notable example of success is North Carolina’s Neuse River, which American Rivers is naming the River of the Year for 2022. This national honor celebrates community leadership and spotlights progress for clean water and river health.

Before the Clean Water Act was signed into law in 1972, the Neuse River was choked with pollution from textile mills and other manufacturing. The federal safeguards provided by the Act, combined with local efforts to stem polluted runoff, improve water management, and remove outdated dams have been the major drivers in the river’s ongoing recovery. Over the years, local governments, the state, and EPA have invested millions to upgrade failing wastewater facilities, reduce polluted runoff, and protect critical areas of the watershed.

While we celebrate the progress of the Clean Water Act on the Neuse River and nationwide, we also have a lot more work to do. Too many people today do not have access to safe, clean water, and too many rivers aren’t safe for fishing and swimming. Climate change is already increasing the frequency and intensity of both floods and droughts. And freshwater animals are going extinct at twice the rate of ocean or land-based animals. Systemic injustices disproportionately burden communities of color with pollution and flooding. And with the Supreme Court considering SACKETT V. EPA, federal protections for rivers and streams nationwide hang in the balance.

Any weakening of national clean water safeguards would be a disaster. The Sackett v. EPA case could throw out 50 years of clean water protections — 50 years of reasonable, rational safeguards — that our rivers, communities and our families rely on.

Our river health must not go backwards. As we celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Clean Water Act, American Rivers stands with our partners and frontline communities to ensure we uphold key protections and to make further progress to realize the vision of clean water and healthy rivers everywhere, for everyone.

Clean water and rivers must unite us. Because when different people, in their own ways from their own places, pull together toward a common goal, we can create positive, transformational change.

The situation on the Colorado River continues to get worse. For months, there has been abundant news about falling lake levels (Lake Powell is below 25% full, and Lake Mead is hovering below 30% full) and while some areas of the west had a terrific monsoon, other areas were left high and dry. Now consider a forecasted La Nina winter (could be the third in a row,) which generally features a warmer and dryer season and reduced snowpack throughout the West, including the Rockies; the confluence of a grim water year is staring at us in the face.

Without being overly melodramatic, the reality is that unless some serious decisions are made, and fast, we could be facing the difficult reality of very little to no water being able to pass through Glen Canyon Dam, in essence creating a Grand Canyon without the guarantee of a flowing Colorado River. For anyone who has been on the river, whether on a raft trip or hiking to Phantom Ranch or trout fishing at Lee’s Ferry, this is a frightening vision. But what would someone who simply peers over the edge of the Canyon at the South Rim, enjoying the expanse and color and light of the distant rocks and buttes – does it matter to them that the small, silver ribbon in the distance is actually dry, rather than wet? Does it matter to people that the very thing that helped create, and certainly supports the web of life, culture, and connection of one of the grandest landscapes in the world, could be reduced to a mere trickle if we don’t take action – and soon? Are we ok with that scenario?

Let’s review what all this means in a practical sense. You may know that the Bureau of Reclamation, the Federal government agency that oversees/manages many of these big reservoirs and the Colorado River system overall, publishes a set of forecasts periodically to try to “project” what lake levels might be – usually up to two years into the future. These are called “24-month studies” and they take scores of different scenarios into account to forecast where the lake levels might be given varying amounts of runoff, soil moisture, snowpack, different temperature possibilities, and how much water is being used in different places across the entire basin. This all feeds into planning how much water needs to be stored, or how much can be released and when, for Lake Powell, Grand Canyon, and Lake Mead, among other federal facilities within the system. These predictions impact millions of people across the Southwest, and across the country when we start to consider that the vast majority of vegetables grown for our winter food supply rely on Colorado River water.

On average, about 8 million acre-feet of water (just one acre-foot is a football field of water, one foot deep, or just over 326,000 gallons) flows from Lake Powell to Grand Canyon in a normal year. But what happens if that number is drastically reduced, or water can’t safely flow through the dam at all? What happens then? Already this year, nearly a million-acre feet has both been sent downstream (from storage in Wyoming’s Flaming Gorge Reservoir) and held back in Lake Powell to slow the fall of the lake. Right now, there is only about 7 million acre-feet flowing into the Canyon in 2022. But levels are still declining, and we are getting closer to the point where Glen Canyon Dam cannot generate electricity, and potentially even worse, where water really can’t safely flow through the dam at all. What if those flows ultimately consisted of about 10% of what flows today – and all from seepage and springs dotting the length of the canyon itself?

Now back to the most recent 24-month study, where Reclamation projects through what they call the “minimum, most, and maximum probable” hydrology projections. For the first time in the history of these projections, the minimum probable projection indicates that Lake Powell could decline to a level where no electricity can be generated (below elevation 3,490ft) by as early as December of 2023. But that says nothing about the efficiency of that power, since the lower the lake gets, the weaker the power generation capability is.

Below that, water would need to be released through tubes that have never been tested for sustained use. Limited space exists where water can still flow through the dam, supplying water to Grand Canyon and Lake Mead, but not generating any power. Overall, this space is only 120 feet, then the lake would be at “dead pool” (at elevation 3,370 ft.) which is in essence exactly how it sounds – a pool of water not flowing through the dam at all.)

So how much more water needs to be held back in order to keep Lake Powell on life support? JOHN FLECK, ERIC KUHN, AND JACK SCHMIDT CONTEMPLATE THAT VERY QUESTION AS THEY SET FORTH THE RATIONALE FOR DOING KEEPING LAKE POWELL FUNCTIONAL IN AN ARTICLE THEY AUTHORED LAST WEEK.

We know that the Federal government has emphatically said that they will protect “critical infrastructure” which means Glen Canyon Dam and both the hydropower and water supply systems that depend upon it. We also know that there are many rules that dictate how this whole system is managed. The Colorado River community is comprised of 7 states, as well as the Republic of Mexico and the Department of Interior, along with stakeholders that include municipalities, irrigators, hydropower customers, recreationalists, and environmentalists. Each hold varying interests in different parts of the Basin, but all must find a way to participate as a whole within the Basin that sustains us all. Critical to considering the Basin going forward also requires recognition of the 30 Federally recognized Tribal nations which have long been left out of the decision-making process around the river. Their rights and role as it relates to the river can no longer be overlooked. Their opportunities to participate are gaining and they should be even more deeply included in decisions going forward. In short, nobody can go it alone, and everyone needs water security and predictability to plan for the future.

Fleck, Kuhn, and Schmidt argue that now might be the time for Reclamation to impose a restricted flow through the dam of only 5.5MAF – ~ 30% less than “normal” flows and still another 13% less water than is flowing into Grand Canyon today. And last week, the Bureau of Reclamation proposed “Moving forward with administrative actions needed to authorize a reduction of Glen Canyon Dam releases below seven million acre-feet per year, if needed, to protect critical infrastructure at Glen Canyon Dam.” This proposal would attempt to keep at least some water flowing through the hydropower turbines (and further lower the levels at Lake Mead) but would keep electricity flowing in both. But what impact would this have on the Grand Canyon ecosystem, including the four species of native fish, the coldwater fishery above Lee’s Ferry, and the amazing diversity of plant, animal, and bird life throughout the Canyon? What would happen to the vibrant and sought-after rafting industry, which between both private and commercial trips, ferry’s more than 26,000 people per year through one of the most amazing, humbling, and majestic landscapes on earth? And maybe most importantly, where does this leave the cultural and spiritual considerations that water flowing through the Canyon has for the various Tribal communities that consider the Colorado River and Grand Canyon sacred places – essential to their way of life?

Can everyone come together with a solution to at least hold the river and the two reservoirs it feeds to a level that would at least triage the situation? If not, what then? While hypothetical, we need to recognize that a nearly dry or severely depleted Grand Canyon in a few short years is more plausible than ever. For anyone who has ever done a river trip leaving at Lee’s Ferry, you know that the Paria River comes in just a mile or so below the put-in, but that is a highly unpredictable river – often either pretty small or nearly dry much of the year, or a raging torrent during the monsoon season.

The next “reliable” water coming into the Canyon is at the Little Colorado River, 75 miles from the dam – and 75 miles is a long way when there is so much riding on the health and sustainability of this ecosystem. Some water from seepage around the dam does occur, but with lowering lake levels, does that seepage get reduced as well? So many unknowns are staring us all in the face.

The upshot is that this is a scary time in the Colorado River system, with many options to consider – rules and laws, and treaties to follow (or change) and lots of people depending on getting it right. And increasingly important in all this, is that getting it right means getting it right together – the possibility of litigation or other legal action would define the worst-case scenario, as any opportunity for compromise and collaboration and finding solutions together instantly stops the minute the first lawsuit is filed.

The 22-year drought and its associated aridification of soils and plants, the exposure of more than 40 million people to water shortage, the whole country being impacted by the potential of reduced food production, and in the middle of all this, one of the seven wonders of the world and the ecosystem, and people, who are deeply connected to this place. Where do we go from here?

The rivers in South Carolina could run out of water. And under existing state law, South Carolina government is allowing all water flow to be legally sucked from a river. In essence, this was the determination that the federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) made when it disallowed state water withdrawal rules because they are not scientifically defensible and do not protect clean water and aquatic wildlife. It is the first time EPA has rejected a state water flow standard. The EPA decision is a big step in a decade-long effort by American Rivers and our partners- Upstate Forever and the Southern Environmental Law Center. These groups threatened to sue the agency if it did not review the state water withdrawal law and associated regulations for compliance with the Clean Water Act.

Healthy, flowing rivers in South Carolina have been in jeopardy since the passage of the South Carolina Surface Water Withdrawal, Permitting, Use, and Reporting Act which went into effect in 2012. The law and associated regulations created the state’s first regulatory program for water withdrawals. That’s the good part. The law also set a statewide minimum standard that is woefully inadequate for protecting aquatic life, fishing, boating, and downstream users. It allowed withdrawers to take up to 80% of a river’s average annual flow. Even worse, the regulation exempted agricultural withdrawers from maintaining flows during low flow periods meaning they could keep taking water until the river is literally sucked dry.

American Rivers and partners brought attention to the failures of the South Carolina policy by listing the South Fork of the Edisto River as a Most Endangered Rivers® in 2014 and the entire Edisto River in 2015. These rivers have been most heavily impacted by excessive water withdrawals. Despite substantial public sentiment against the implementation of the law – an estimated 400 people vocally opposed to the mismanagement of South Carolina’s water participated in a January 2014 public meeting – the South Carolina legislature was unmoved by this outcry to end the agricultural exemption and make other changes needed for protecting river health and recreation uses.

Finally, the EPA ruled in May of this year that South Carolina’s water withdraw law was not in compliance with the Clean Water Act. The nation’s bedrock environmental law, the Clean Water Act was written by Congress to protect and restore the biological, chemical and physical quality of the nation’s waters. Federal courts have affirmed numerous times that ensuring healthy water flows falls under the Clean Water Act. You can’t have a healthy river without enough water!

EPA has ordered South Carolina to stop using its state water withdrawal law and accompanying regulations for any Clean Water Act related permitting decisions. The state is now in the process of developing new, protective standards for stream flow and lake levels. This will hopefully produce a new regulation and recommendations to the state legislature that would be scientifically defensible and ensure the health of the state’s rivers and lakes.

Specifically, the EPA found:

- The South Carolina Surface Water Withdrawal, Permitting, Use, and Reporting Act set a water quality standard as defined by the Clean Water Act for regulating water flows and lake levels;

- The state law also set a water quality standard as defined by the Clean Water Act for “safe yield”, the amount of water that can be withdrawn from a river or lake;

- These two standards do not protect the “biological, chemical and physical integrity” of the state’s waters and are, therefore, in violation of the Clean Water Act;

- South Carolina cannot use these standards for any Clean Water Act purposes; and

- The state must develop new water quality standards during 2022 and submit them to EPA for review to ensure compliance with the Clean Water Act.

This precedent setting decision is a big step in preventing excessive water withdrawals and harmfully inadequate minimum flow requirements that have threatened the state’s rivers for a decade. It opens a new path for water management in South Carolina and provides an example to other southeastern states for protecting our region’s rivers and ensuring enough clean water for people and nature.

Did you know that poster sized section of stream bottom in the Southeast US can have more species of freshwater mussels than the all the streams in Europe?

There are more species of freshwater mussels in the Southeast US than anywhere else in the world – even in the Amazon Rainforest! These filter-feeding animals keep your drinking water clean and keep your water bill down as dirty stream water is more expensive to turn into drinkable water.

While we have stunning diversity of freshwater mussels, we also have a problem. Populations of freshwater mussels are declining and scientists do not know why yet. American Rivers is partnering with scientists across 13 states to figure out what’s going on.

Recently, the field crew was near Rome, GA, and we started our morning with First News with Tony McIntosh on WRGA to talk about our work to stave off biodiversity loss.

As end-of-summer fires blanket western Montana in thick smoke, it is too hot to sit on the banks of the Thompson River but too cold to stand in the water for more than a few minutes. While Montanans have withered in 90+ degree temperatures for most of the summer, many of our rivers, like this one, have remained ice cold. But the cold water is just one of the top three reasons American Rivers is telling the Forest Service to protect 57 rivers in the Lolo and Bitterroot National Forests as Wild and Scenic Eligible.

#1 Cold Water

Trout like water that is ice cold.

Cold water is a climate shield. From Blue Joint Creek in the Bitterroot Mountains to the West Fork Thompson River near Thompson Falls, western Montana boasts 35 rivers that serve as a climate refuge for cold water fish like Bull Trout and Westslope Cutthroat Trout. New climate science fish habitat maps show that headwater streams will be some of the few places cold enough by 2040 for cold water fish to survive. A recent study on climate impacts on Montana’s fishing economy found that cold-water river segments support ten times more anglers than warm-water segments. This brings visiting anglers to the state of Montana and keeps local anglers fishing close to home. Overall, cold water in Montana’s headwaters streams is good news for both fish and anglers.

#2 Close to Home

Wild and scenic rivers aren’t just for extreme athletes in remote outdoor places. In fact, 20% of river miles we’re recommending as Wild and Scenic Eligible are readily accessible by roads and include well-known local gems like:

- Rock Creek, an iconic blue-ribbon trout stream just outside Missoula with ample camping

- Lower Clark Fork River, a family floating destination near St. Regis with placid fishing stretches, deep swimming holes, and boat ramps for all kinds of watercraft

- Clearwater River, a popular canoe trail nearly Seeley Lake with stunning views of the Swan Mountains

Recreational wild and scenic rivers provide close-to-home recreation with easy access for Montanans of all backgrounds, skill levels, and athletic abilities.

#3 Our Culture

Although outdoor recreation itself is a key part of how some might define “Montana culture,” the cultural ties to our rivers run much deeper and longer for Indigenous Peoples. Our rivers, including 18% of those we are recommending as Wild and Scenic Eligible, are significant to the current and historic cultures of the Séliš (Salish), Qlispé (Kalispel and Pend d’Oreille), Kootenai, Ktunaxa, Nimíipuu (Nez Perce), and Schitsu’umsh (Coeur d’Alene) Tribes, among others. Cultural values are an important reason to protect rivers like:

- Rattlesnake Creek, a historic Indigenous fishery

- Sleeping Child Creek, a site from Indigenous creation stories known as Snetetšé (Place of the Sleeping Baby)

- Sweathouse Creek, a place to build sweat lodges

- West Fork of the Bitterroot River, where generations of Séliš (Salish) harvested edible valerian root, an important medicinal plant

Eligible for What?

Wild and Scenic River protections are truly made-in-western-Montana. In the 1950s, University of Montana wildlife biologist John Craighead and his brother Frank were fighting fast and furious dam proposals. They were frustrated. Wouldn’t a law protecting the country’s remaining few free-flowing rivers be a better way? After years of organizing, Craighead’s dream became law when the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act was signed in 1968. Wild and Scenic Eligible rivers protected as part of National Forest plans are waiting their turn for the permanent protections offered under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act.

American Rivers’ new Lolo and Bitterroot Wild and Scenic Eligibility Report highlights all 57 special rivers on the Lolo and Bitterroot National Forests in Western Montana and will be a key tool in convincing the Forest Service to protect them as Wild and Scenic Eligible. Along with the voices of local community members, we can influence upcoming forest planning processes to ensure that rivers like these remain cold, clear, and free-flowing for many hot summers to come. During forest planning, rivers can receive Eligible Wild and Scenic River status, meaning that they are protected for the life of the forest plan (usually around 20 years). Eligible Wild and Scenic Rivers are protected for their fisheries, climate refuge, cultural, scenic, recreational, and other values while ensuring they are protected from dams, diversions, de-watering, erosion from stream-side logging, and other activities that can make them inhospitable to fish and dangerous for boaters and anglers. During Montana National Forest plan revisions completed since 2015, American Rivers and other local partners successfully convinced the Forest Service to double its river protections. On National Forests near Helena, the Flathead, Yaak, and Bozeman, more than 1000 river miles are now protected as Wild and Scenic Eligible within four National Forest plans that will remain in place for decades.

What’s My Role?

As a Montana community member, resident, visitor, or Indigenous Nation citizen, you can help our Western Montana Office. Sign up so you can get action alerts when it’s time to comment on river protections during the upcoming Lolo and Bitterroot forest plan revisions. Use this interactive map of eligible rivers to learn more about each individual rivers and its special values.

To contact our Western Montana Office, email or call Lisa Ronald, Western Montana Associate Conservation Director, at lronald@americanrivers.org, 406-317-7757.

It was a lot of water. More water than I’m used to seeing rushing towards the canyon section of Northwest Washington state’s North Fork Nooksack River. A few stomachs flipped as we peered over the bridge at the thousands of cubic feet of water blowing right past us, but the excitement of rafting those giant waves quickly took over.

American Rivers recently had the pleasure of co-hosting a whitewater rafting trip with a local nonprofit organization called the Vamos Outdoors Project — a group, based in Whatcom and Skagit counties, whose mission is to build community through connection to the land and access to the outdoors.

American Rivers recognizes that conservation and environmental education traditionally underserves Latine, Migrant, and Multilingual communities, disconnecting them from their rivers and the environmental threats that disproportionately burden their communities. We wanted to create a fun experience for the youth of these communities — one that would foster new advocates who will engage in Northwest river protection efforts for years to come. Thus, the idea of a river rafting trip was born.

Eleven students and two trip leaders from the Vamos Outdoors Project piled out of the van on a drizzly morning in early June, all brimming with excitement. They wriggled into their wetsuits, and everyone’s safety equipment was checked for proper fit. A few students grew nervously quiet as we approached the bridge under which we would launch the rafts. The river was raging at over 3,000cubic feet per second. Spring runoff had just peaked, and Mt. Baker was shedding her winter coat directly into the Nooksack. It was a lot of water—beautiful and breathtaking.

The professional guides conducted a thorough safety check and tested our knowledge of the paddling commands. We then set out on the first section of our trip. Hoots and hollers filled the canyon for several miles. Nearly everyone was beaming as we pulled over on the river for lunch.

I introduced the students to a handy way of remembering the five Pacific salmon species that call the Nooksack River home. They also collected macroinvertebrates (bugs that salmon like to eat while they rear in freshwater) and discussed the life cycle of Pacific salmon. A restoration staff member from the Nooksack Indian Tribe talked about some of the threats the river faces (logging, irresponsible recreation, dams, etc.). The Nooksack people have stewarded this watershed for centuries, and today, the Tribe’s restoration team implements several projects throughout the river, including the installation of engineered log jams that provide habitat for all life stages of salmon and steelhead. Through their efforts, and those of numerous partners, habitat is recovering from erosion, the riparian forest is reconnecting to its river and floodplain, and dams like the Middle Fork Nooksack Dam are being removed to restore a free-flowing river.

After two devoured watermelons and a near-stampede when the brownies came out at the end of the lunch hour, we were all back on the river together. The sun had emerged to illuminate a whole mess of smiles, disappearing behind and then rising above the river waves.

We closed the trip by sharing our rose, bud, and thorn: one thing about the trip that you really enjoyed; one thing that you want to improve upon; and one part that was particularly challenging. Following the paddling commands and changing stroke patterns on a dime, were challenging for most. But for eleven students doing a highly adrenaline-inducing activity for the first time, I was elated to hear that so many of the kids were looking forward to “next time.”

Trips like this one are dynamic ways to engage Latine and Migrant youth, who aren’t always offered the opportunity to get to know their river in this way. Creating opportunities to interact with and learn about the river builds and strengthens connections and understandings of the North Fork Nooksack River’s ecosystem, the people who rely on it, and the work being done to protect and enhance it – work such as the Nooksack River Wild and Scenic effort. Since 2012, American Rivers and several local partners have been working to secure permanent protections for the Nooksack River, which will allow for the protection and restoration of all five Pacific salmon species and steelhead; protect the river’s clean water used for drinking, farming, outdoor recreation, and tourism; and ensure the river remains free flowing. We were also able to introduce the students to the Maple Creek River Access Site—a plan put together in collaboration with the Washington State Department of Natural Resources, Whatcom Land Trust, American Whitewater, and others which will, once completed, provide public recreation access along the North Fork Nooksack River, while also allowing natural resource managers to protect, restore, and enhance the adjacent riparian forest and natural river systems.

This trip was made possible by the generous support of the Wilburforce Foundation, Superfeet, the Mountaineers Foundation AKA the Keta Legacy Foundation, and the Norcliffe Foundation. We are so grateful for your support of this trip. Thank you for supporting these youth, their education, and their budding roles as river advocates.

Language Note: Vamos Outdoors Project uses the terms ‘Latine,’ ‘Migrant,’ and ‘Multilingual’ to refer to their community and their students.

On August 16, 2022 President Biden signed into law the Inflation Reduction Act, which will provide an estimated $369 billion to tackle climate change over the next decade. That’s a big number, but what does it mean for rivers?

Overall, this is a bold step forward, as it provides a significant investment that would cut carbon emissions by 40% by 2030, and provides over $30 billion in financial assistance for green house gas reduction projects. In a country like the U.S. where passing climate change legislation can be difficult, these investments could be game- changing.

Here are some key provisions:

Drought Response

$4 billion for water infrastructure modernization projects, as well as projects to reduce harmful effects of drought on rivers and inland water bodies. This comes in three main forms:

- Water users would be compensated for voluntary reductions that are made in water deliveries.

- Conservation projects to help bolster water levels in the Colorado River system would receive funding support.

- Environmental restoration projects to mitigate damage from drought conditions will be a central priority.

The funds, to be administered by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation over the next four years, could be used to pay farmers, rural districts and others to fallow crops and in- stall efficient watering technology, or to pay for other voluntary water reductions in the Lower and Upper Colorado Basins, which combined provide drinking water and irri- gation to nearly 40 million people across seven states and Mexico.

Tribal Nations

$12.5 million through FY 26 for near-term drought relief actions to mitigate drought impacts for Indian tribes that are impacted by the operation of a Bureau of Reclama- tion water project.

$220 million for tribal climate resilience and adaptation programs, and $10 million for fish hatchery operations and maintenance programs at the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Conservation and Climate Resilience

$3 billion in grants to states, tribes and municipalities and community-based nonprofit organizations for financial and technical assistance to address clean air and climate pollution in disadvantaged communities.

$3 billion in investment to help reduce air pollution and carbon emissions at and surrounding our nation’s ports. Most of our nation’s ports continue to use antiquated diesel technology that pollutes our air, harms our planet, and is not fuel efficient.

$250 million for wildlife recovery and to rebuild and restore units of the National Wildlife Refuge System and state wildlife management areas. Restored habitat will mit- igate the impacts of climate-induced weather events and increase resiliency, benefit- ting wildlife and surrounding communities.

$2.6 billion for NOAA to assist coastal states, the District of Columbia, Tribal Gov- ernments, local governments, nonprofit organizations, and institutions of higher edu- cation to become more prepared and resilient to changes in climate.

$190 million for high performance computing capacity and research for weather, oceans and climate.

$50 million for NOAA to administer climate research grants to address climate challenges such as impacts of extreme events; water availability and quality; impacts of changing ocean conditions on marine life; improved greenhouse gas and ocean carbon monitoring; coastal resilience and sea level rise. This research will provide the science that Americans need to understand how, where, and when Earth’s conditions are changing.

$12 million to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to develop and implement recov- ery plans under Section 4(f) of the Endangered Species Act of 1973. Section 4(f) of the Endangered Species Act requires the Secretary to develop and implement recov- ery plans for listed species.

$250 million to carry out projects for the conservation, protection and resiliency of lands and resources administered by the National Park Service (NPS) and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM).

$250 million to carry out conservation, ecosystem and habitat restoration projects on lands administered by the NPS and BLM.

Environmental Justice

$1.5 billion to plant trees, establish community and urban forests, and expand green spaces in cities, which combats climate change and provides significant community benefits by increasing recreation opportunities, cooling cities, lowering electric bills, and reducing heat-related death and illness.

$50 million for investments in Urban Parks through grants to localities for acquisi- tion of land or interests in land, or for development of recreation facilities to create or significantly enhance access to parks or outdoor recreation in urban areas.

$397.5 million for programs aimed at building resilience across Tribal govern- ments and communities by providing support to transition electrified homes to re- newable energy sources and provide renewable energy to homes without electricity; address drinking water shortages and provide financial assistance for drought relief; maintain and operate hatcheries; and fund Tribal climate resilience and adaptation programs.

$550 million to ensure disadvantaged communities have the resources needed to plan, design, and construct water supply projects, particularly in communities and households that do not currently have reliable domestic water supplies.

$1 billion to improve Energy Efficiency or Water Efficiency or Climate Resilience of Affordable Housing, that help covers the cost of energy efficiency upgrades.

$1.9 billion to support efforts to improve walkability, safety, and affordable transportation access, including natural infrastructure and stormwater management improvements related to surface transportation in disadvantaged areas.

Energy

$260 billion in new and extended clean-energy tax credits meant to incentivize energy companies and public utilities to produce more solar, wind and hydropower energy.

It also expands or creates a host of new environmental tax credits for electric vehicles, residential and commercial buildings, certain manufacturing, and carbon sequestration.

Wildfire Protections and other Forestry improvements

$5 billion to protect communities from wildfires while combating the climate crisis and supporting the workforce through climate-smart forestry, including:

- $2.15 billion for National Forest System Restoration and Fuels Reduction projects

- $1.8B for hazardous fuels reduction projects on National Forest System land within the wildland-urban interface

- $200M for vegetation management projects on National Forest System land

- $100M for environmental reviews by the Chief of the Forest Service

- $50M for the protection of old-growth forests on National Forest System land and to complete an inventory of old-growth forests and mature forests within the National Forest System

Plus $2.75 billion for investing in climate-smart forestry to boost carbon sequestration and another $1.5B to provide grants for tree planting and related activities.

It has become clear that there’s another threat looming just over the horizon for California – a megaflood. A new study from Daniel Swain and Xingying Huang of UCLA provides dire modeling of how climate change will impact weather patterns throughout the state, with periods of unprecedented rainfall expected to increase in frequency and intensity in the years to come. There is no telling exactly when the event will occur, but the research has made it clear: the storm is coming.

This superstorm, often referred to as atmospheric rivers, will put California’s flood mitigation infrastructure: levees, dams, floodplains and more to the ultimate test. Communities in the floodplains of the Central Valley are especially vulnerable and face the greatest risk from flood events that haven’t been witnessed in our lifetime. American Rivers has put together 3 key priorities to prepare for these drastic changes, inspired by an article published by the New York Times on August 12th.

Reconnect rivers to their natural floodplains

Over the past century, California’s rivers have been confined by levee construction and cut off from their historic floodplains. Our rivers have limited capacity to spread and slow flood flows, increasing the risk of levee failure and catastrophic flooding. By connecting rivers to their historic floodplains, we make room for rivers to flow naturally during high flood events while replenishing groundwater aquifers and reconnecting wildlife habitats. These multiple benefits (or “multi-benefit”), nature-based solutions are essential to landscape-level climate resilience and are a comprehensive natural solution to the impacts of anthropogenic climate change.

Invest in multi-benefit, nature-based flood risk reduction solutions in the Central Valley

As noted in the New York Times article, investments in flood risk reduction infrastructure have been inadequate given the rapid pace of climate change. Federal and state agencies have been unable to meet their goals of reducing flood risk reduction benchmarks, leaving poor communities vulnerable to severe flooding. We need diverse coalitions of legislators, flood managers, conservationists, and farmers to advocate for more federal and state funding dollars to support more flood risk reduction projects and better planning for the floods in our future.

Limit urban development in high-risk floodplains

Floodplains are areas where rivers would flow and undulate across the landscape if they were not constricted by levees – and they are the most at risk for flooding and levee failure. While levees are often built to protect critical infrastructure—such as highways and airports— this can lead to further development on lands presumed to be protected by the levee. Building entire neighborhoods and commercial facilities in high-risk floodplains next to critical infrastructure places lives, jobs, and entire regional economies at risk. By limiting urbanization in floodplains, we can reduce the amount of damage we expect to be caused by increased flooding.

These priorities guide our work in California’s Central Valley, where American Rivers designs and implements on-the-ground flood resilience projects and advocates for state and federal policies that keep communities safe. If you would like to stay up to date on our work in California, check out our California Region page.

Waterfalls are something to behold. Whether five feet tall or 200 feet tall, there is just something about cascading water that captures your attention. But what classifies falling water as a waterfall? How many different kinds of waterfalls are there? Is Niagara Falls the biggest waterfall in the world?? We’ve got the answers to these common questions about waterfalls below.

Can all falling water be considered a waterfall?

Not exactly. To be deemed a waterfall a segment must be at least five feet high. To further qualify, according to Milestone Press, the waterfall must come from a river, creek, or stream that provides water at least annually.

Fun Fact: There is a town in Connecticut that claims to have the smallest natural waterfall in the United States. This is a bold claim! The town of Newington, Connecticut claims that Mill Pond Falls, originating from Mill Pond, is the smallest in the United States, and even holds a Waterfall Festival every year to honor the falls’ so-called fame and contribution to town history. Coming in at 12 feet high, it is pretty small. What do you think? Do you know of a smaller waterfall? Please share your thoughts in the comments below. You can find out more about Mill Pond Falls here.

Okay so after we have deemed it a waterfall, what kind of waterfall is it?

There is a long list of different types of waterfalls, but the main differentiator is how the water descends. For times sake, we’ll touch on the most common.

Tiered or Multi-step Waterfall

A series of waterfalls one after another of roughly the same size, each with their own sunken plunge pool.

Example: Yosemite Falls in Yosemite Valley

Plunge Waterfall

A vertical fall that flows without making any contact with the underlying cliff face.

Example: Rainbow Falls in Hilo, Hawaii, on the Wailuku River.

Cascade Waterfall

Falls that have a series of rock levels onto which the waterfalls

Example: Cascade Falls, along Little Stony Creek which feeds into the New River

Horsetail Waterfall

Water falling in a vertical drop, then making contact with the rock surface behind the water, causing the water to spray out or change direction from the original path.

Example: Horsetail Fall which is created from rain or snow melt merges with the Merced River in Yosemite National Park

Fan Waterfall

A falls that widens at it’s base

Example: Union Falls along the Fall River in Wyoming

Is Niagara Falls the biggest waterfall in the world?

The short answer is no, however, there is more to the story. Niagara Falls is certainly not the tallest in the world. The title of the tallest known waterfall is held by Angel Falls, located along the Amazon River in Venezuela, which falls an incredible 3,212 feet. Niagara Falls does, however, hold the title for “World’s Highest Flow Rate” at 700,000 gallons of water flowing down the falls every second.

Another commonly unknown fact about Niagara Falls is that it is actually made up of three falls:

- American Falls

- Bridal Veil Falls

- Horseshoe (Canadian) Falls

All of these falls originate from the Niagara River which receives water from four of the Great Lakes, emptying into the 5th lake, Lake Ontario.

Waterfalls are fascinating!

This blog was written by American Rivers Hydropower Reform Intern Katherine Tara.

As climate change fuels increasingly severe floods and droughts, the value of clean, healthy rivers becomes even more essential. And as we prioritize and increase investment in low- or no-carbon energy sources, it’s vital that we have all the information about costs and benefits of alternatives to fossil fuels.

While hydropower dams will continue to play a role in our nation’s energy portfolio, it is important to acknowledge that both reservoirs and hydropower generation contribute to greenhouse gas emissions.

Here’s what you should know about emissions impacts of reservoirs and hydropower:

Q: Should hydropower be considered clean energy?

A: Hydropower should not be labeled “clean” or “green” because of the damage dams cause to rivers, fish and wildlife, communities, and cultural values, and because of the greenhouse gas emissions produced by reservoirs. 80% of these reservoir emissions are methane – a greenhouse gas that is 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide.

Q: About how much methane is emitted from reservoirs annually?

A: Estimates show that hydroelectric and non-hydroelectric reservoirs emit approximately 13.4 million metric tons of methane per year, with nearly half of that coming from hydroelectric reservoirs.

Q: How is methane emitted from reservoirs?

A: Methane is emitted from manmade reservoirs through several pathways including (1) continuous diffusion across the surface of the reservoir; (2) bubbling (“ebullition”) from sediments; and (3) transport through plants growing within the reservoir.

Q: Do hydropower facilities generate more methane than non-hydro reservoirs (for example, reservoirs only used for water storage)?

A: Yes. The energy generation technology that turns a dammed reservoir into a power source can contribute to the methane emissions of the reservoir in a variety of ways. The turbines release methane that is dissolved in the water and ultimately increase GHG emissions. In addition, hydropower operations can dramatically raise and lower reservoir levels, exposing sediments, which releases methane.

Q: Does the Environmental Protection Agency keep track of GHG emissions from reservoirs?

A: Sort of. Greenhouse gas emissions from hydroelectric reservoirs were inventoried in the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) 2020 report to quantify emissions from the energy sector.This report estimates that in 2020, reservoirs and other artificially flooded lands produced 797 kilotons of methane, annually. EPA estimates emissions generally, but hands-on measurement of emissions at individual reservoirs is necessary to better understand the problem.

Q: What does American Rivers make of this whole situation?

A: American Rivers believes that a large-scale reservoir methane emissions measurement program would be beneficial for honing emissions models and allowing scientists, regulators, and dam operators to better anticipate the consequences of an increasingly warming climate on reservoir methane emissions. American Rivers joined partners to sign this call to action, urging EPA to improve tracking.

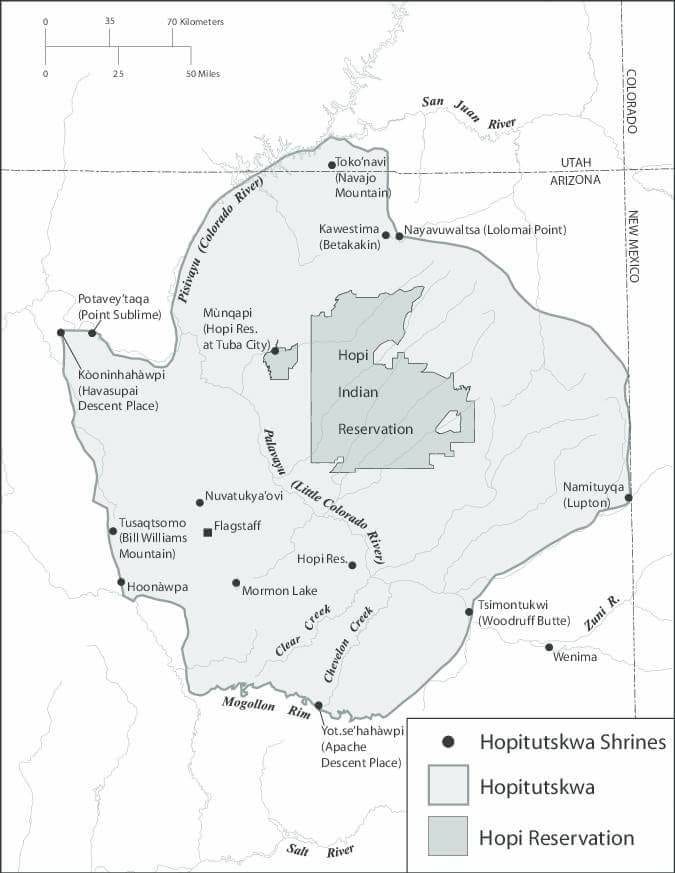

For two early mornings in Spring, Hopi leaders, elders, and advocates joined with EcoFlight, American Rivers, and the Grand Canyon Trust to fly over Palavayu, or the Little Colorado River. This is no small feat for a 340-mile-long river. The primary purpose of the flights was to offer Hopi elders and cultural leaders—the people who’ve mostly experienced Palavayu through song, culture, and religion—an opportunity to behold the river and Hopitutskwa, the Hopi ancestral lands, in their entirety and to engage in conversations about their protection.

Viewed from the air, an impressive landscape unfolds in which Palavayu (“red river”) flows through the center of Hopitutskwa. Nuva’tukya’ovi, the peaks near Flagstaff, rise to the West, still capped in snow in mid-April.

Hopitutskwa occupies much of the 17.3-million-acre Little Colorado River watershed. Flying towards the headwaters from Winslow, Homol’ovi—an ancestral Hopi settlement along the river—and Tsimontukwi, or Woodruff Butte, come into view. We observe the massive scale and impact of the three coal-fired power plants that operate exclusively on the groundwater below Palavayu. Notably, these stations withdrew a combined average of 36,100 acre-feet of groundwater per year between 2001-2005 and continue significant withdrawal to this day, directly impacting the river’s baseflow and communities downstream who rely on both the river and the Coconino aquifer.

When we turn and fly northwest towards the confluence with Pisisvayu, or the Colorado River, the layers and shadowed canyon of Öngtupqa—Grand Canyon—clarify in the early morning light. Soon we’re over Sakwavayu—Blue Springs—and then the site of the proposed Big Canyon Dam, a place which is as undeniably beautiful as it is undeniably inappropriate for a project that would pump billions of gallons of ancient groundwater to fill four reservoirs for the sheer speculation around cheap hydropower.

But, the flights facilitated much more than the viewing of the landscape. The experience generated conversation about how to advocate for the river and how to include elders in the process. It helped Hopi community members feel respected and included in the work to protect the river and provided an opportunity for them to share their expertise on the issues that are important to them. It supported younger generations of Hopi advocates in demonstrating good intentions and provided an opportunity to learn proper Hopi place names. It also helped to build trust between Hopi and non-Hopi partners.

“Lack of access to information—this is what is driving people’s concerns. No one has been communicating with us at Hopi or explaining what’s happening.”

Increasing access to information about threatened places, including creating opportunities to witness these places firsthand, is a critical part of conservation advocacy. Many of the participants in the flights were unaware of the Big Canyon Dam proposal and many more yet in communities along the Little Colorado River don’t have access to this information or what can be done. We’re working on multiple fronts to change that. One critical next step is that Hopi filmmaker, Victor Masayesva Jr., will be using footage gathered during the overflights in a forthcoming Hopi-language film titled “Sípapuni” about Palavayu and its attendant cultural landscape. The film will be shown in upcoming outreach events throughout Hopi villages and communities, encouraging all Hopi to engage in the effort to safeguard this incredibly important river.

We’re grateful to the Hopi Cultural Resources Advisory Task Team, Hopi Cultural Preservation Office, and Hopi Tribal Council for participating and to our partners at EcoFlight.

This opinion piece originally ran in the Louisville Courier Journal on August 2, 2022.

I remember sitting on our porch in Catlettsburg, holding my cabbage patch doll watching the torrential downpour and continuously glancing at Shopes Creek as its waters crept nearer and nearer to our home.

I remember the putrid smell after a flood and the way mud hung around for weeks and weeks climbing up our legs. I remember the critters upended from their homes and into basements across the region that kept children away from those parts of the house in perpetuity.

I remember my Granny talking about the flood of 1977 and how the scars of that one flood alone completely shaped – and still shapes – the story of the community as a floodwall was built to divorce people from the river, but also from the water, which was the lifeblood of the neighborhood.

Communities like mine and those flooded out in the last few weeks, live these realities constantly. And it’s just getting worse as climate change fuels increasingly severe storms and floods. In 2020, the U.S. saw an average annual loss of $32 billion from flooding, and that cost could rise by up to $41 billion by 2050, according to a study published in Nature. Low-income, Black, Latino and Indigenous communities are disproportionately impacted. Flooding has always kept people in poverty and that will just get worse, unless we take action.

My heart aches for my neighbors, but I have hope. Because even while rivers are where we’re feeling the devastation right now, rivers are also the source of powerful, equitable, cost-effective solutions.

There are proven ways to keep people and property safe along rivers, while reaping all of the benefits a healthy river offers. We can restore floodplains (the low-lying areas along rivers) and wetlands, giving rivers room to safely accommodate floodwaters. We can improve land use and change how we build, so runoff doesn’t overwhelm downstream communities. We can also help people get out of harm’s way− in some regions of the U.S., communities have successfully relocated to higher ground.

It’s critical that every community understands their options, can advocate for their own safety and well-being and determine their future. That is why American Rivers is calling on the Biden administration to take emergency climate actions in support of healthy rivers. Here are three steps the administration can take right now to support hometowns like mine and other vulnerable communities nationwide:

Help people find safety

The administration should require FEMA and HUD to better integrate programs for affordable housing with floodplain management to meet the housing needs of people who need to relocate to safer ground. The lack of resilient affordable housing remains a huge barrier for families looking to move away from flood prone areas. The need for climate-resilient, affordable housing is critical to frontline communities as they recover from and prepare for extreme weather.

Send resources to vulnerable communities

The administration can help states improve flood management, both reducing flood damage − particularly for disadvantaged communities − and protecting and restoring natural floodplains. We must reduce the gap in FEMA resource availability for low-income communities of color, which often don’t have the municipal staff required to be eligible for pre disaster mitigation programs.

Protect and restore rivers

The administration should establish a National Floodplain Protection and Restoration Program to better use federal floodplain management programs to protect and restore the nation’s floodplains as carbon sinks and reduce flood damages. The initiative should set national goals for protection and restoration for floodplains, coordinate floodplain data collection, create mapping and prioritization tools and equitably distribute flood resilience funding to states.

We can break the devastating cycle of flood damage. We can give communities the tools they need to lift themselves out of poverty. We can create a future where healthy rivers and people thrive together.