The Salmon-Challis National Forest in central Idaho, headwaters of the world-renowned Salmon River, is currently revising its forest plan. This process occurs just once every 20 years or so, making it incredibly important that the Forest gets it right. While getting a new Wild and Scenic river designated by Congress often takes upwards of 10 years, forest plan revisions have the potential to protect dozens of free-flowing rivers through the planning process – a once in a generation opportunity.

Part of the plan revision process is inventorying and protecting the remaining free-flowing streams on the Forest that qualify as “outstanding” under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. The Salmon-Challis National Forest has done a great job on its draft inventory, finding 69 streams totaling 708 miles to be free-flowing and possessing at least one outstanding value. But opposition groups are pressuring the Forest to protect far fewer streams, and in some cases none at all.

We need your help. Please send a comment to the Forest supporting the protection of all streams in the Salmon-Challis National Forest’s “Draft Wild and Scenic Eligibility Inventory.”

Comments on the Draft Eligibility Inventory, due July 16, can be emailed to: scnf_plan_rev@fs.fed.us.

For more information, take a look at the Forest’s story map to review their recommendations. You can also submit a supportive comment through their portal. For those who want to dig even deeper, take a look at the Forest’s Draft Eligibility Report.

During the year of the 50th Anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, and at a time when public lands are being assaulted from all directions, we need more of our last free-flowing rivers to be protected, not less. Thank you for your help!

This blog is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series on the Mississippi River Gorge.

Mussels – the Brita filters of the animal world – are the most endangered animal in North America due to habitat degradation in rivers.

In this video, the female federally-endangered snuffbox mussel hides in the gravel bed waiting for a common logperch to flip it like a pebble. When the logperch touches the female snuffbox, she grabs the fish by the nose while ejecting her baby glochidia, who will attach themselves to the logperch’s gills to feed until they grow large enough to settle in a gravel bed.

Not to worry! The logperch is unharmed by the encounter.

No other small fish can survive the snuffbox’s attention, making the logperch its obligate host. In other words, the mussel is totally dependent on the logperch for the survival of its species.

While the snuffbox mussel and the logperch lived in the Mississippi River Gorge historically, the habitat is not suitable today because of two dams.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/4987/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”4″ center=”yes”]Take Action »[/su_button]

The Klamath River was once the third largest producer of salmon on the West Coast. But for nearly 100 years, four dams have blocked salmon and steelhead from reaching more than 300 miles of historic habitat, and have caused toxic algae outbreaks that harm water quality all the way to the Pacific Ocean, more than 190 miles away.

That’s all about to change, with the most significant dam removal effort in history. And today, we marked an important milestone in the push to remove the river’s four dams — J.C. Boyle, Copco 1, Copco 2, and Iron Gate. The Klamath River Renewal Corporation, the entity managing the dam removal project, submitted its plan to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, as part of its application to transfer the license for the four dams and remove them.

Demolition Details

Known as the Definite Plan, the 1,500-page document provides comprehensive analysis and detail on project design, decommissioning, reservoir restoration, and other post-deconstruction activities.

For example, the plan describes how the reservoirs behind the dams will be drawn down, or drained, carefully and relatively slowly in a process that will take two to three months. Demolition of the dams will follow during the dry season (June to October). A five to ten-year restoration plan will ensure lands formerly inundated by the reservoirs are stabilized and restored with native plants.

What comes next? FERC will use the information to make a decision on the license transfer application. If FERC approves the transfer application, it will then turn to the dam removal application – the final approval we need. We are hopeful that the project will stay on track, with dam removal beginning in 2020.

Smart Move for Ratepayers

Dam removal makes sense from both an environmental and an economic perspective. The four Klamath dams produce a nominal amount of power, which can be replaced using renewables and efficiency measures and without contributing to climate change. In fact, since we started working on this project over 10 years ago, 10 times as much wind, solar and geothermal capacity was produced than is provided by these dams.

In 2008, the Public Utilities Commissions in Oregon and California concluded that removing the dams, instead of spending more than $500 million to bring the dams up to 21st century safety and environmental standards, would save PacifiCorp customers more than $100 million..

The World’s Biggest?

The Klamath River project will be the most significant dam removal and river restoration effort yet. Never before have four dams of this size been removed at once which inundate as many miles of habitat (4 square miles and 15 miles of river length), involving this magnitude of budget (approximately $397 million) and infrastructure.

But perhaps more important than the size of the dams is the amount of collaboration and the decades of hard work that have made this project possible. American Rivers has been fighting to remove the dams since 2000. And thanks to the combined efforts of the Karuk and Yurok tribes, irrigators, commercial fishing interests, conservationists, and many others, our goal of a free-flowing river is now within reach.

This blog is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series on the Mississippi River Gorge.

Rivers connect us.

Not just in the wild lands of Montana or through the great canyons of the West, but they are the life force of many urban centers. This is the case with the Mississippi River Gorge… and in this case, our urban river connection could be even stronger if we remove the dams that keep it tightly harnessed.

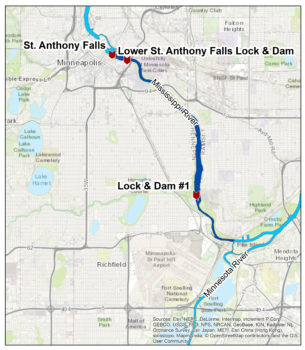

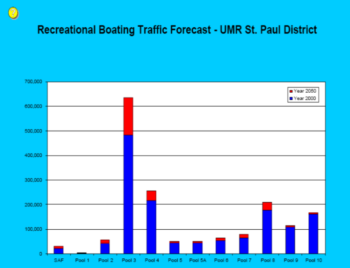

The Mississippi River Gorge runs approximately eight miles from Saint Anthony Falls in downtown Minneapolis to the Minnesota River confluence in Mendota, Minnesota. In the Gorge, steep bluffs extend to the waterline and are mostly undeveloped throughout the Mississippi National River and Recreation Area. Parkland and walkways parallel the top of the bluffs, and some areas are crisscrossed with hiking trails. From the water, recreational boaters experience a feeling of remoteness even though they are paddling through a major metropolitan area. However, despite the river’s proximity to the city’s center and its National Park designation, it has the fewest number of recreational boaters on the Upper Mississippi River Navigation System in the St. Paul District.

Although within the most populous area of the river, Pool 1 has the least recreation with no projected growth assuming present conditions continue. (Click to enlarge.)

The Gorge is impounded by two navigation dams that also produce hydropower: Lower Saint Anthony Falls Lock and Dam, and Lock and Dam 1.

These dams are impacting a river corridor that supports many state and/or federal species of concern, including black buffalo fish, paddlefish, northern long-eared bat, eleven species of mussels and Blanding’s turtle.

This year, there is an opportunity to restore part of an untamed Mississippi River and bring back fish and wildlife exiled a century ago.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is currently studying Lower Saint Anthony Falls Lock and Dam, and Lock and Dam 1, to determine if it is in the taxpayers’ best interest to continue paying for maintenance and operation of the structures. This study will also determine if other federal, state, local, non-profit and private entities are interested in future ownership of the properties. Upon completion of the study, the Army Corps will submit recommendations to Congress on the fate of the infrastructure. This study provides a rare opportunity to influence the future of the Mississippi River Gorge and residents’ connections with the river.

It costs about $1.5 million annually to operate and maintain the dams and locks in the Mississippi River Gorge. On top of this routine funding, the infrastructure must be overhauled about every 50 years to extend the life of the infrastructure. Such major rehabilitation work can cost around $45 million per site.

If the Army Corps decides to keep the dams in place, aquatic habitat in the Gorge could continue to decline for a generation or more. On the Upper Mississippi River, habitat is degrading faster than it can be restored through existing conservation programs, and the river’s dams are a primary cause of declining aquatic habitat.

Saint Anthony Falls was once one of four big river rapids on the Upper Mississippi. Today, a lone remnant of the St. Louis Chain of Rocks rapids is all that remains. While the Gorge’s bluffs have been mostly protected as public parkland, the dams remain blocking access to unique habitat for fish and wildlife and stifling natural river processes.

Lower Saint Anthony Falls Lock and Dam | Olivia Dorothy

The dams in the Mississippi River Gorge were built to support an industry vision dating back to the 1800s. Although the dams currently produce hydropower, their capacity is tens of thousands of kilowatts below the 55,000-kW national average, and their actual production is lesser still. Keeping the dams in place would require millions of dollars annually to safely maintain the infrastructure, some of which is a century old, while the river’s ecosystem continues to degrade.

The time is ripe to take a bold step forward towards a new vision of the Gorge that removes the environmentally damaging features of a 150-year-old industrial plan, restores the natural flow and character of the river, rehabilitates habitat for fish and wildlife, and promotes compatible recreation and business opportunities.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers should move towards a solution that removes the dams in the Mississippi National River and Recreation Area.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/4987/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”4″ center=”yes”]Take Action »[/su_button]

The first half of June have been nothing but hot and dry for most communities in Colorado. On the Front Range, temperatures have soared into the high nineties, and in numerous places across the state, wildfires have flared, darkening the skies with smoke and threatening local economies as tourists remain at home. Across the state, we are seeing – and feeling – the impacts of our dry winter.

Rivers form the lifelines of Colorado’s economy, environment and lifestyle. They impact every aspect of our lives, providing most of our clean, safe and reliable drinking water, supporting thriving farms and ranches, and contributing to culture, heritage and recreation. During a dry summer like this, we can easily identify the impacts that healthy, flowing rivers have on our communities and quality of life.

Those who enjoy spending time on or near rivers have likely noticed the lower – and earlier – flows we experienced this year. The Colorado River peaked about 4 weeks earlier than normal, and at the GoPro Games in June, flows through Gore Creek were less than half of the normal discharge. On the upper Yampa above Steamboat Springs, fishing has been restricted below Stagecoach Reservoir to help protect fish in this reach. And farmers and ranchers are radically changing their normal operations to ensure they protect their livelihood at this time of dwindling irrigation water in their ditches.

As this summer presses on, we certainly will continue to be impacted by the dry year. But there is hope, and things each of us can do to help conserve our critical water resource, including reducing shower times, limiting outdoor watering, and educating yourself about the health of our rivers and streams – including ways you can support more conservation and flexibility across the state. It’s now more important than ever to increase your awareness about where your water comes from and how water moves throughout the state.

Earlier this summer, we produced an illustrated guide, called “Do You Know Your Water, Colorado?” to explain the long, complicated journey a drop of water takes from its home in a river to your tap. As a Coloradan, it’s our responsibility to understand how water is moved from place to place across our great state and the role we all have in protecting our state’s flowing rivers and the clean, safe, reliable drinking water they provide.

Always, but especially in a dry year like this, we must meet future water demands without sacrificing our rivers and everything they support. Our communities, economies, environment and drinking water supply depend on all of us working together. Can our rivers count on you to help move Colorado’s water future forward?

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/5080/petition/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”4″ center=”yes”]Take Action and support Colorado’s rivers »[/su_button]

This guest blog was written by Sarah Evans and is a part of our blog series on America’s Most Endangered Rivers® – Rivers of Bristol Bay, Alaska.

I grew up in the Bristol Bay, the salmon capital of the world. My family first lived in Manokotak, a small village on the Igushik River. When we moved there, my mom wanted to make friends right away, so she brought me down to the beach where all the local women were filleting salmon. And she asked if she could help. But when my mom brought out a filet knife, the women busted up laughing, they said, “Are you crazy? We don’t use a man’s knife here,” and handed her an ulu and taught her to fillet salmon the Yup’ik way.

I should pause to explain my mom a bit, she was beautiful and was always done up to the nines. She always had perfect makeup, with bright pink lipstick – the lipstick was her signature look. She loved pink anything and loved wearing high heels. At the time, Dillingham had mostly dirt roads, but she still wore heels most days.

When I was seven, my family moved from Manokotak to Dillingham, a larger community, where every fall they held the No-See-Um Festival, which includes a salmon filleting contest. Local women competed to see how many salmon they could filet in 10 minutes. Our first fall, my mom walked over to sign-up, and I could see the locals giving her strange looks as if to say, ‘who the hell is this fancy chick,’ and laughing at her pink rubber boots (bought from a Martha Stewart catalog). But sure enough, my mom annihilated all of them in the contest with her ulu! Jaws dropped to the ground. I have never been so proud or seen my mom so happy. And from that moment on, I was hooked on salmon.

I’ve spent every summer completely salmon-obsessed. I have been a commercial fisherman, a sport fisherman, and massive subsistence user of salmon. I have studied salmon from an anthropological and biological perspective. But my greatest salmon accomplishment was earning my spot at the fish splitting table.

The splitting table is a sacred place. It’s where women gather together to do much more than just put salmon away for their family to eat throughout the winter. To be able to join the table is a rite of passage, and an honor you have to earn. When I was a kid I wanted so badly to be at the table – I wanted in on the jokes and secrets. I desperately wanted my own ulu! But I had to work my way through the ranks: umping fish guts, making sure there were buckets of water to clean the table, hanging fish strips in the smokehouse, and other chores. When I was 16, I had made it through the gauntlet, and I had a spot at the table – and my very own ulu. Finally, I was able to laugh with the women because I was in on the jokes, the stories, the secrets and the drama. I thought of us all as the Queens of the Bristol Bay!

Not long after, my community and many others became aware that the salmon that hold our communities together was threatened by the Pebble Mine. So for more than a decade, we’ve been fighting to ensure that there would be splitting tables for generations to come. The fight has had its ups and downs, but through it all, we’ve never lost hope and never given up. And along the way, there’s been some fun.

A few years back, we got the greenlight to host a Salmon Day at the Alaska State Fair. We decided to do salmon print t-shirts with kids – give parents a break from their sugar-riddled kids, and give kids a fun salmon memento to take home. The night before we left Dillingham for Anchorage to go to the fair, we realized we didn’t have any salmon to use for the prints! No problem, right? We were Queens of Bristol Bay. We could get up early catch some silvers before flying out. Of course, that plan didn’t go as expected, and we only got two fish from our expedition.

We knew we needed more for the booth, as hundreds of people would be at the fair. But it was late August, and we couldn’t find anyone with whole fish still. Everyone had processed theirs for winter. Still, we were Queens of Bristol Bay. We thought we could catch some around Anchorage.

Our crew of Bush Rats in the Big City started trying to find our natural habitat. We got a tip that there were some great creeks north, and headed out. By the time we find some salmon in a shallow creek, it is dark out, and we couldn’t see much. We manage to catch a few humpies with our bare hands and toss them in a garbage bag. Back at the hotel, we shoved the garbage bag into our mini-fridge, having never looked at our catch. The next morning we wake up and the whole room smells unbearable. We open the fridge, and completely rotten, mushy salmon fall out. Even if we could use them without puking, they’d fall apart on the first print. Now out of time, we realize we’re going to have to settle for herring purchased at a nearby fish market.

The shirts were still a hit, the parents were happy for a break from their kids, and we lived to fight the Pebble Mine another day.

I am fighting the Pebble Mine so I can help protect Alaska’s most valuable resources: our clean water, our clean air, our fisheries, wildlife and our people! I’m fighting so that all of us can pass on our knowledge, our stories, our experiences to the generations to come, and so that one day we all have a chance to make it to the fish splitting table. I know that if my mom were still alive she’d be standing here right next to me with her heels on and a one-of-a-kind pink No Pebble Mine t-shirt on, fighting with us all.

Sign-on by June 27th to be included in our petition!

Editor’s Note: You can also listen to Sarah’s story here.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/5000/petition/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”4″ center=”yes”]Take Action »[/su_button]

Sarah Evans is from Dillingham, Alaska, newish to Anchorage. She spends most of her free time outdoors with her two dogs, or sitting somewhere with a drink in her hand obsessing over Alaskan politics.

This guest blog was written by Jenny Weis with Trout Unlimited. It is a part of our blog series on America’s Most Endangered Rivers® – Rivers of Bristol Bay.

Standing in a carpeted, sterile event hall next to identical rows of beige, cushioned chairs, my eyes welled up with tears as I watched the propaganda video put forth by the Pebble Partnership detailing their phase-one plans to build a massive mine at the headwaters of Bristol Bay.

Thirty years ago, a vast, low-grade deposit of gold and copper was found in the hills of a water-rich saddle within the remote region in southwest Alaska, at the headwaters of two of the eight major rivers that flow into Bristol Bay. The same year of the discovery, a little over four thousand miles away, I’d just been born.

The region sustains world-class sport fishing and hunting, and an Indigenous subsistence culture that has thrived for millennia. The Bay itself is a famous commercial fishery that supplies over half the world’s sockeye salmon. Pebble mine backers are asking us to trade the gold in the hills for the salmon in the rivers. Thousands of Alaskans and a million Americans have spoken up in response, and have resoundingly and repeatedly said, “no way.” Yet the company presses on.

Over the past two weeks, I watched from afar as residents of rural villages dotting the region have packed tiny community centers and school gyms to tell the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the agency in charge of reviewing one of Pebble’s most critical permits, their concerns about the proposed Pebble Mine. Seated in mish-mashed accumulations of folding chairs, Native Elders stood and spoke about how the mine would impact their clean water and traditional fishing and subsistence hunting and gathering practices that have been passed down for generations. It was sometimes hard to discern their testimony through thick Yup’ik accents, grainy cell phone videos due to poor connection, or tears. Commercial fishermen feared that any impacts would destroy the fishery and thus, their livelihoods and the trade they planned to pass onto their children. They were visibly frustrated — after dozens of hearings and meetings, why did they have to say this all over again?

The scenes couldn’t be more different in Anchorage.

Protesters outside the Anchorage meeting hosted by the Army Corps of Engineers. April 19, 2018. | Brandon Hill

There was no opportunity for public testimony in Anchorage, Dillingham — the largest community in the Bristol Bay region, or in Homer — the largest community on the Kenai Peninsula, near the proposed gas pipeline and additional 250MW power plant the company proposes to build. It’d take too long to get throughthe hundreds of comments in opposition, said the Corps of Engineers.

Impassioned testimony was replaced with a single, sterile video produced by Pebble with a faceless, robotic voice over discussing the company’s massive plans. The opportunity to publicly testify was replaced with a court reporter in a side room who would transcribe a private, oral statement.

The video displayed prominently on a large screen upon entering the meeting. Describing what would need to be dug up to access the gold and copper, the very landscape of Bristol Bay — things like trees, vegetation, wetlands, fishing rivers, and wildlife habitat, the video used the word, “overburden.” The video said Pebble would closely monitor wildlife activity on the tailings ponds, but left out the end of that very sentence, which is, “because it will be toxic.” It explained that once the phase-one mine was done with operation, Pebble would replace all the material they remove from the pit and “revegetate.” This word struck me as something that would almost be funny — imagining hard-hat workers trying to replace the wild character on vast amounts of ground they’d unearthed, if it weren’t so depressing and impossible.

Clearly, this fight has absolutely nothing to do with me. I was hired by Trout Unlimited’s Alaska program in 2014 to help their army of concerned lodge owners and anglers organize, following the lead of the Native community, and help get the word out that the science is in, and the mine would be catastrophic to the businesses and cherished fishing opportunity, as well as the livelihoods of those that live in Bristol Bay now and have since time immemorial.

As I’ve gotten to know the people who’d be personally impacted by this proposal over the last four years, it has become clear why testifying against this project could make you cry, even if it’s your 10th or 50th time doing so.

It’s hard not to shudder when a robot explains that 160,000 tons of mine waste per day would be trucked down roads that would have to cross 200 salmon streams, introducing concrete and fences to a wild region wherein those two items are now uniquely absent. It’s not uncommon to see a room full of shaking heads when the company brags that no longer using cyanide in their plans is its claim to “environmental responsibility,” despite that the very mineral they seek to unearth, copper, is lethal to wild salmon even in trace amounts. And you can’t help but wonder how the mine backers sleep at night promising the mine will be safe while knowing that NO mine in modern history has safely contained toxins from the surrounding environment at this scale.

I know that if Pebble Mine goes through, my life will likely carry on as usual. Alaska’s economy will take a hit, and the world’s supply of salmon will be altered. But I have no skiff to leave to my children or smokehouse to continue filling the way ancestors did before me. Pebble banks on the fact that most of their opponents recognize this, and will eventually give up.

But on behalf of the people I have met in the last four years, whose lives and whose children’s lives will be irreparably altered by this proposal, I’ll be damned if I don’t do everything I can to ensure that Bristol Bay remains characterized by the one thing it has since before time: wild salmon. The Pebble Mine proposal doesn’t fit into this picture.

So, you can bet I’ll be standing there with them, behind them, at as many meetings as it takes until the robot videos, arrogant foreign investors, and unfair permitting schedules are a thing of the past.

Sign-on by June 27th to be included in our petition!

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/5000/petition/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”4″ center=”yes”]Take Action »[/su_button]

Author: Jenny Weis

Jenny Weis works for Trout Unlimited‘s Alaska Program. She lives in Anchorage. Trout Unlimited is working with anglers, local communities and businesses to stop Pebble Mine and put long-term protections in place for Bristol Bay, Alaska.

Jenny Weis works for Trout Unlimited‘s Alaska Program. She lives in Anchorage. Trout Unlimited is working with anglers, local communities and businesses to stop Pebble Mine and put long-term protections in place for Bristol Bay, Alaska.

This guest blog was written by Tipton Power, a member of the Nooksack Wild & Scenic campaign steering committee and is actively engaged in the Bellingham paddling community.

Nothing defines the arrival of prime paddling season more than the subtle roar of rapids and splashes of cold water, fresh from the deep winter snowpack, which wake up the senses and help you appreciate nature’s cycles and seasons in another way.

Late spring is in full effect here in the North Cascades and as the temperatures warm up in the higher elevations, the North Fork Nooksack River rises to prime levels for paddling and rafting. It’s time to just get back in a boat any day of the week and let the current whisk you away down the river.

Whitewater Paradise

From its origins on the slopes of the glacier-dotted Mt. Shuksan, the North Fork Nooksack tumbles down steep boulder gardens and cuts narrow canyons through lush inland rainforests, picking up flows from major tributaries like Glacier, Canyon, and Wells Creeks. Along the banks, everything seems covered in a thick mat of moss and ferns appear to grow from everywhere you look.

The upper reaches of the North Fork offer expert paddlers tight gorges with class IV and V white water separated by a couple of waterfall portages. Below that is a short but steep Class IV(+) section ending at the Horseshoe Bend campground. From the campground down to the town of Glacier, the river leaves the highway again and runs through a beautiful mini-gorge with lots of quality Class II and III water. It is a great day stretch for kayaks and rafts that instills a sense of remoteness and adventure close to home.

Why Wild & Scenic?

Residents in the area are lucky to have such a gem of a river in their backyard. As well as having recreational and scenic values, the Nooksack River is also critical spawning habitat for salmon, steelhead, and trout, a source of clean water to the communities downriver, unique geological features (ever seen the Chuckanut sandstone formation?), and cultural values to the Coast Salish people.

Over the past century, there have been more than 50 proposed hydropower projects within the Nooksack River basin and without Wild and Scenic protection, it leaves the river vulnerable to these ever-present threats. This alone is why I think it is time for us as a paddling community—a river community—to get behind the designation of the forks of the upper Nooksack River and nine key tributaries as a Wild and Scenic River and give this small slice of paradise in the North Cascades the protection it deserves.

Sign the petition and learn more about the Nooksack River Wild & Scenic Campaign.

This guest blog was written by Katherine Carscallen and is a part of our blog series on America’s Most Endangered Rivers® – Rivers of Bristol Bay, Alaska.

As I type this blog, I can feel my fingers sting with layers of cuts and grime. Looking at my Band-Aid and grease saturated hands, I’m reminded that it was never my intention to be a mechanic. In no way do I mean to disparage mechanics, I’m often gratefully indebted to them. It’s just that I grew up on my parent’s commercial fishing boat.

I was always drawn to the bridge of the boat, watching the net go out, fish pile in, and my favorite part, picking each fish out of the net, one by one as they come aboard. Picking fish is a race against yourself, to get the salmon out as quickly as possible while taking care to remember that each one will end up on a person’s plate in the near future.

Fishing to me was always intense. Exciting. An adventure. And of course when we were lucky – lucrative.

It wasn’t long after college I knew I wanted fishing to be a permanent part of my life and I bought my boat. That was my first inadvertent step towards becoming a mechanic. I learned very quickly that in order to do the fun parts of fishing, you must first ensure your engines, hydraulics, steering, pumps, and every other detail of the boat is maintained to run without fail at a critical moment. Without all the equipment we depend on running well, I would never have the opportunity to put my net in front of the world’s largest runs of wild salmon year after year in Bristol Bay. So, this time of year, with an estimated 51 million salmon only a week or two away, I guess I am a mechanic, anxiously awaiting my chance to be a fisherman again.

When I decided to make fishing my career, I also never intended to become an environmental advocate.

By the same token however, the un-paralleled fishing here in Bristol Bay is only possible thanks to generations of people caring for the habitat that sustains our salmon. Centuries ago, healthy salmon runs were all over the West Coast, unobstructed by dams, sediment, roads and other inevitable side effects of industrialization.

Today, those runs are diminished, and Bristol Bay is now unique. It’s the last great wild sockeye run in the world, and the habitat that sustains our watershed has not been damaged by development. Keeping our fishery intact means advocating for the habitat that sustains it.

Ever since a Canadian company called Northern Dynasty proposed to build what would be one of the largest mines in North America just upstream from my home in the headwaters of our two most important salmon rivers, I’ve become an environmental advocate too.

Today, the Pebble Mine is closer to becoming a reality than ever before. Northern Dynasty has entered the federal permitting process. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is taking comments on the impacts the mine would have – this is the first phase in the permit application’s environmental review.

I’ve already submitted my comment, asking that the Army Corps consider the downstream impacts this mine would have. I asked them to consider the generational threat a toxic tailing dam would pose, the economic harm the existence of a mine would have on our fishing industry that is rooted in quality, sustainability and pristine wild salmon. I asked them to prioritize thousands of years of tradition and a way of life sustained by the people of this region, and to consider the permanent and irreversible harm this mine would bring to an otherwise unaltered watershed, as one mine after another was built on top of our salmon nursery.

This is our opportunity to take a different path than the places where salmon runs have already been decimated. We can still prioritize water, salmon, people and Bristol Bay’s world-class fishery.

So, while I anxiously await the coming salmon, I’m taking a break from my boat work to ask you to submit a comment as well. Please support the last great wild sockeye fishery, and the pristine habitat that sustains it.

Sign-on by June 27th to be included in our petition!

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/5000/petition/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”4″ center=”yes”]Take Action »[/su_button]

Katherine Carscallen is a commercial fisher woman and lifelong resident of Bristol Bay.

This guest post by Dr. Jason Sellers is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Rappahannock River.

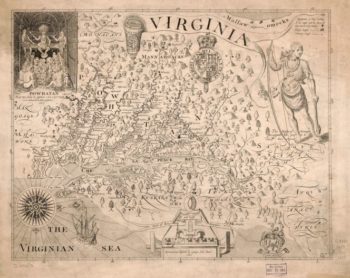

The Rappahannock River has long been a focal point for Virginia’s human communities, and its health remains vital for Virginians today. Although often confident in the resilience of their natural resources, including the Rappahannock, Virginians have historically taken steps to protect the river and the opportunities it provides. Concerted efforts since the 1960s have revitalized the river, its industries, and its people, even as new threats imperil the Rappahannock today.

For centuries, anadromous fish runs and fertile soils have attracted Native Americans to Virginia’s river valleys. Algonquian peoples, many of them associated with the Powhatan chiefdom, centered their territories on the major waterways on which they relied for food and travel. John Smith met a number of these groups as he explored the Chesapeake in 1608, including the Rappahannock tribe, whose name means, “the people who live where the water rises and falls,” and from whom the river takes its name. Smith also received reports of Manahoac settlements above the Rappahannock’s fall line.

English colonists found Virginia’s rivers attractive for similar reasons, dispersing across plantations on level, fertile land near the waterways that could carry their tobacco and wheat to market. As settlement expanded inland, the House of Burgesses ordered the construction of Fredericksburg in 1728, at the fall line of the Rappahannock. The town was to serve as a distribution center connecting backcountry settlers and the area’s emerging iron industry with Atlantic trade networks. Several years earlier, Governor Alexander Spotswood had established German iron workers on the Rapidan River, the Rappahannock’s largest tributary, and by 1720 Spotswood’s Tubal Furnace was operational, later providing iron for Fredericksburg’s gun manufactories during the American Revolution.

Although the new federal government declined to designate Fredericksburg as a port-of-entry, investors hoping to position the Rappahannock as a regional trade hub constructed an extensive canal system. When the system failed to turn a profit, the Fredericksburg Water Power Company transformed it in 1855, constructing a wooden crib dam to direct water into the canals for water power rather than transportation, and enlivening Fredericksburg’s thriving agricultural and industrial mills. The company modernized this operation in 1910, constructing Embrey Dam to channel water through turbines at its new power plant to provide electricity for the growing region’s industries. The plant ceased operations in the 1960s when power demands exceeded what local water power could supply, but the canal system continued to provide raw water for the city into the early 2000s.

By the turn of the 21st century, intensive agricultural and industrial development had been shaping the Rappahannock for three centuries, and a major dam had obstructed it for over 150 years. As early as 1759, upstream residents complained that mills obstructed fish runs, and the General Assembly ordered mill owners to build fishways through or around their dams — an early example of political action to protect valuable marine species. The watershed’s extensive timbering and mining had less obvious but equally damaging effects on the river’s health, the former removing ground cover and eroding the banks of the river and its tributaries, the latter leaving open slag piles to leach into streams. To protect and manage the valuable fisheries on the Rappahannock and throughout the commonwealth, the state tasked a series of agencies with regulating its finfish and shellfish industries beginning in the 1870s. Similar concerns about industrial pollution, as well as municipal wastewater discharge, led to one of the nation’s first water control laws in 1946 to protect municipal water sources.

Virginia thus had a long history of environmental protections by the time the General Assembly created the Virginia Outdoor Recreation Study Commission in 1964 amid a mounting environmental movement. Anticipating that the mix of counties, cities, and towns comprising Virginia’s metropolitan areas would complicate land-use planning, the Commission’s 1965 report called for regional planning and action when multiple localities shared a resource, identifying waterways and river basins as particular concerns. That report and the 1966 Virginia Outdoors Plan became the underpinning for subsequent legislation that created an open-space easement program designed to protect watersheds, scenic views, historic landscapes, and wildlife habitats by permanently removing land from development. Since 1988, more than forty organizations have secured over 500,000 total acres of perpetual easements in the state.

Such easements constitute one crucial tool for regional conservation efforts on the Rappahannock River. As part of a larger flood control and water supply project, the City of Fredericksburg purchased 4800 acres of forested riparian lands along 32 miles of the Rappahannock and Rapidan rivers in 1969, later converting more than 4000 acres into a conservation easement in 2006. Residents along the river have responded to environmental concerns as well, some formalizing their efforts by founding the Friends of the Rappahannock (FOR) in 1985. Besides securing its own property and establishing additional conservation easements, FOR has been instrumental in raising environmental awareness by combining a range of educational and restoration programs throughout the watershed with political advocacy on behalf of the river and its residents. As co-founder Bill Micks explained in 2017, “Almost everybody from top to bottom on this river now realizes the importance of a green 100-foot buffer or 200-foot buffer and how important that is for water quality. I think things have really taken a step in a good direction.”

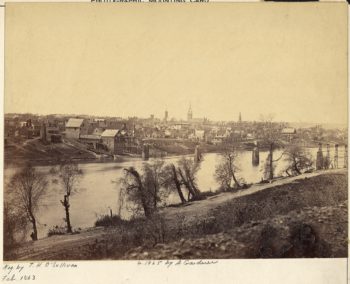

Perhaps the most visible moment in the Rappahannock’s recovery came with the removal of Embrey Dam. Concerns about declining migratory fish stocks and the poor condition of the dam dovetailed with desires to restore the river and boost tourism, and local officials and conservationists cooperated to secure congressional support. A 1998 federal study determined that fish passage and the restoration of the Rappahannock was in the public interest, qualifying the dam removal project for federal funding. After removing 250,000 cubic yards of accumulated sediment, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers used explosives to breach the dam in 2004, removing the rest in 2005 to restore a free-flowing Rappahannock for the first time in 150 years.

The outcome of years of coordinated efforts between the state, the city of Fredericksburg, federal agencies, the military, and non-profit organizations, the removal of Embrey Dam is a reminder of both the challenges and possibilities inherent in protecting regional watersheds like the Rappahannock from new threats like fracking. Remembering events of the early 2000s, Chief Anne Richardson of the Rappahannock Indians recalls, “We had a tradition of pouring salt in the water to cleanse and so we went and poured salt in the water and prayed that the creator would come because he created this river, it belongs to him, not us. And so we asked for purification and healing and he did it.”

Through the efforts of the citizens and governments it serves, the Rappahannock today is the longest free-flowing river in Virginia. The last decade has seen migratory fish returning to the river’s upper reaches, oyster populations rebounding in the tidal estuary, the river’s banks revegetated, bald eagle nesting sites multiplying, residents and tourists boating and hiking, and a cleaner water supply for the region’s inhabitants. Centuries ago and today, from the mountains to the bay, a healthy Rappahannock remains a center of Virginia life.

FOR THREE YEARS IN A ROW, the Virginia General Assembly has rejected industry attempts to roll back important fracking chemical disclosure rules that would apply to natural gas development in the Rappahannock River Basin. This idea, to keep chemical secrets from the public, continues to rear its ugly head. Despite defeating these bills in past Virginia General Assembly sessions, there is currently another legislative attempt to erode these protections sitting in a subcommittee of the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Council and may end up in the Virginia General Assembly for a FOURTH YEAR IN A ROW. This is unacceptable.

[su_button url=”https://salsa4.salsalabs.com/o/50930/p/dia/action4/common/public/?action_KEY=25010″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”4″ center=”yes”]Take Action »[/su_button]

Dr. Jason Sellers is a professor of history at the University of Mary Washington in Fredericksburg, VA. He is a cultural and environmental historian of 17th-and 18th-century North America interested in landscapes and bodies, and is currently working on a project that explores the interactions of Munsee Indians and European colonists in the 17th-century Hudson Valley.

This blog is a part of our series on America’s Most Endangered Rivers® – the Big Sunflower River in Mississippi.

The Big Sunflower River topped our annual list of America’s Most Endangered Rivers® this year. Have you been there? Have you paddled or fished in this special place? Tell us your story below!

In case you’ve never been there (sadly, I have not either), I wanted to share some beautiful images that capture many of the curious creatures that call this place home (and some whimsical commentary that you can take or leave). These images are all credited to Stephen Kirkpatrick.

Check out the stack of alligators above! I suspect they must have been keeping warm by piling up (this image was taken in March). Or perhaps they are waiting in line for the all-you-can-eat buffet!

Did you know that armadillos can swim? I did not. Yet, here is this rolly polly stretching out and taking a dip in the river. It reminds me of a tiny amphibious tank.

Did you know that armadillos can swim? I did not. Yet, here is this rolly polly stretching out and taking a dip in the river. It reminds me of a tiny amphibious tank. Whoooooo do we have here? A gorgeous Barred Owl. Did you know that supposedly Barred Owls have a call that sounds like, “Who cooks for you?” Listen here and then tell me below if you agree with the experts at The Cornell Lab of Ornithology (I’m not sure… it just sounds like a bunch of hooting to me… although I admit that I am not a bird expert AT ALL)!

Whoooooo do we have here? A gorgeous Barred Owl. Did you know that supposedly Barred Owls have a call that sounds like, “Who cooks for you?” Listen here and then tell me below if you agree with the experts at The Cornell Lab of Ornithology (I’m not sure… it just sounds like a bunch of hooting to me… although I admit that I am not a bird expert AT ALL)!

Well, I’ll be dammed! While beavers drive some people crazy, they can actually be really helpful for the river environment in some places. If you want to learn more, check out this recent article!

Well, I’ll be dammed! While beavers drive some people crazy, they can actually be really helpful for the river environment in some places. If you want to learn more, check out this recent article!

The beautiful Belted Kingfisher. I love that blue-grey. Of course, I had to compare the soulful hoots of the Barred Owl to this Belted Kingfisher, and HONEY, this bird sounds like it is ordering me around! I don’t know what I am supposed to be doing, but I better get on top of it! (Does this remind you of anyone you know…?)

The beautiful Belted Kingfisher. I love that blue-grey. Of course, I had to compare the soulful hoots of the Barred Owl to this Belted Kingfisher, and HONEY, this bird sounds like it is ordering me around! I don’t know what I am supposed to be doing, but I better get on top of it! (Does this remind you of anyone you know…?)

BARRED OWL: Whoooo cooks for you?

BELTED KINGFISHER: Goodness, you don’t even know. Nobody is cooking for me! Where are my helpers? Nowhere to be found. But you can bet when the food is ready, there they will be with their empty bellies waiting for some tasty fish. Did anybody help catch the fish? Nope. You just don’t even know…

These Black-bellied Whistling Ducks live in the trees and forage at night. Of course, I had to have a listen. Here you go! Definitely less quacky and more chirpy.

These Black-bellied Whistling Ducks live in the trees and forage at night. Of course, I had to have a listen. Here you go! Definitely less quacky and more chirpy.

Don’t you just love the look of this Cattle Egret? It’s as if he just woke up and was like—what did I miss?? Listen to this Cattle Egret having a good laugh about something or other. Not surprisingly, these birds hang out with cows, eating bugs that get rustled up or even ticks on the cows themselves. Gotta love that symbiosis.

Don’t you just love the look of this Cattle Egret? It’s as if he just woke up and was like—what did I miss?? Listen to this Cattle Egret having a good laugh about something or other. Not surprisingly, these birds hang out with cows, eating bugs that get rustled up or even ticks on the cows themselves. Gotta love that symbiosis.

Lots of birds. Something else! Fox squirrel! This one is starring in the new movie: Mission Impawsible. Before it leaves for its mission, it needs to track down some nuts!

Lots of birds. Something else! Fox squirrel! This one is starring in the new movie: Mission Impawsible. Before it leaves for its mission, it needs to track down some nuts!

This is Mississippi. You know there are bugs in this Delta! This is a Hoverfly on a Chickasaw plum bloom. Don’t worry though. Hoverflies are harmless to most other animals.

This is Mississippi. You know there are bugs in this Delta! This is a Hoverfly on a Chickasaw plum bloom. Don’t worry though. Hoverflies are harmless to most other animals.

Look at this momma wild hog with all her hoglets! I cannot imagine having that many babies at one time. Good luck, momma!

Look at this momma wild hog with all her hoglets! I cannot imagine having that many babies at one time. Good luck, momma!

Bird break over. Y’all, I had to share this Indigo Bunting! Look at that stunning blue plumage. What a happy sounding bird!

Bird break over. Y’all, I had to share this Indigo Bunting! Look at that stunning blue plumage. What a happy sounding bird!

Check out this goofy Wood Duck! I think he’s yelling—Stop! We didn’t wait 30 minutes to digest before going in the water! What do you think he is yelling?

Check out this goofy Wood Duck! I think he’s yelling—Stop! We didn’t wait 30 minutes to digest before going in the water! What do you think he is yelling?

Did you know that Red-bellied Woodpeckers have suuuuuper long tongues? Their tongue can stick out nearly two inches past the end of their beak, plus it’s all barby and sticky, to get tasty morsels out of deep crevices.

Did you know that Red-bellied Woodpeckers have suuuuuper long tongues? Their tongue can stick out nearly two inches past the end of their beak, plus it’s all barby and sticky, to get tasty morsels out of deep crevices.

Lastly, we have fabulous Roseate Spoonbills and a cameo by Black-crowned Night Heron. There’s something wonderful about a bright pink bird with a big ole spoon beak that just makes me smile. Nature is a crazy place.

Lastly, we have fabulous Roseate Spoonbills and a cameo by Black-crowned Night Heron. There’s something wonderful about a bright pink bird with a big ole spoon beak that just makes me smile. Nature is a crazy place.

Truly, these magnificent creatures are just a small snapshot of the amazing wildlife that would be impacted by the Yazoo Pumps project in the Big Sunflower watershed. Take action today to help us save this special place.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/4999/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”4″ center=”yes”]Take Action »[/su_button]

If you loved these images as much as I do, go check out more of Stephen Kirkpatrick’s wildlife photography at: https://www.kirkpatrickwildlife.com/index.

The following guest blog from Brian Hanson is part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series on the Middle Fork of the Vermilion River in Illinois.

I am writing in response to an article about the Middle Fork of the Vermilion River published in the Chicago Tribune on April 10, 2018. The river has been selected as one of America’s Most Endangered Rivers®.

I broke into tears when I read it.

I confess to being a bit emotional recently. I’ve been told that it’s a common problem with people who have had death or near-death events and develop a heightened sense of what is or has been important in their life. I had my own near-death experience two months ago and now wear a portable defibrillator.

Seeing the Vermilion River in the paper brought back a favorite memory of my dad, H. Gordon Hanson, a great guy who died way too young. I had high hopes for more quality bonding time with him after he took early retirement from his job. His job? He was a biologist for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. In the early days of his career, it seemed like his job was to try and make the pillage of our environment “look pretty.” But then, the word “environment” became more important. He gave me his copy of “Silent Spring”, the anti-pesticide book by Rachel Carson, to read shortly after it came out. Eventually, his job title was changed from just “Biologist” to “Chief of Environmental Resources Division” for the Army Corps.

For those of you who enjoy fishing for Coho salmon in Lake Michigan, my dad deserves more than a tip of the hat. He was involved in many projects like that during his career with the Army Corps.

He was also largely responsible for the development of recreational areas on Army Corps property along the upper Mississippi. Many campgrounds on Army Corps property there and throughout the Midwest were due to his efforts. If you’ve camped at any of them you can thank my dad.

While I was a student at the University of Illinois in Champaign, Dad came down to spend a little time with me. He suggested that we take – what appeared on the map to be – a reasonably short float down the Vermilion River. He had our clunky old aluminum canoe strapped to the top of the car. The Vermilion was not known as a float stream back in those days, and we soon found out why. It took all of our strength on umpteen occasions to lift that canoe over massive logjams and downed trees. We arrived at our takeout point well after dark. Dad had to hitch a ride (in the dark) to go back and get our car.

Of all my memories of time spent with my dad, that “gentle” float trip down the Vermilion River has been a favorite. Part of his legacy that I cherish is that he had a big part in rivers like the Vermilion becoming National Scenic Rivers. I wonder if I was an unknowing member of his scouting mission that day.

Polluters like Dynegy and others have tried to tarnish my father’s legacy in Illinois and where I live in Michigan. Lake Michigan continues to be threatened with horrific environmental damage if and when Line 5 bursts beneath the Straits of Mackinac.

Our current leadership – or lack thereof – in Washington and in state capitals across the country tell us they want to roll back regulations that protect valuable resources like the Middle Fork Vermilion River.

I have good reason to be crying.

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/4946/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”4″ center=”yes”]Take Action »[/su_button]

Editor’s Note: A more recent article has been published on this issue in the Chicago Tribune. Check it out!

Brian Hanson is an advocate for healthy rivers in Illinois.