This guest blog was written by Karlee Deatherage, a member of the Nooksack Wild and Scenic campaign steering committee and Clean Water Policy Analyst at RE Sources for Sustainable Communities.

On any given day during our sunny, dry Pacific Northwest summers, you can find people out enjoying a variety of outdoor activities, from picking berries at a local u-pick farm, harvesting clams or crabbing in and around Puget Sound, building sandcastles on beaches, or taking a leisurely paddle down a local river or creek. Our way of life here in Whatcom County is inextricably linked to a healthy Nooksack River, and we should do everything we can to protect it as we all live downstream and everyone depends on plentiful, clean water.

When I think of the relationship between summer and the Nooksack River, I also think about how much more water we are using to keep cool and stay hydrated, how much water farmers need for crops like raspberries and blueberries, and the dwindling water levels in tributaries that are key for salmon returning to spawn. Yes, our salmon are incredibly resilient creatures, but there are only so many proposed dams and water diversions or years of insufficient stream flows due to drought that salmon can survive. Conservation of the upper Nooksack basin as Wild and Scenic provides safeguards to the river against these future harmful water projects and dams, and potential mining projects, all of which would have devastating effects on its wild characteristics, ecosystem, recreational amenities and clean water.

The lower reaches of the Nooksack River have already seen significant development, bank hardening, and rerouting of certain stretches of the river. It faces water quality concerns ranging from excessive bacteria to lack of dissolved oxygen to support salmon and other aquatic life. So many community groups, tribes, nonprofits and agencies have put all hands on deck through habitat restoration projects to undo the damage the lower Nooksack has suffered. Thankfully, however, the upper Nooksack watershed — where our communities get their clean water — is relatively intact. I hope we can keep it that way.

A Wild and Scenic River designation for the Nooksack would mean we are able to protect the headwaters from intense development or activities that could impact water quality and might pose yet another threat to our clean water, salmon and way of life. I support a Wild and Scenic Nooksack so our hard work in the lower watershed won’t go to waste and so we can all savor the remaining wild and scenic stretches of the upper Nooksack in perpetuity.

Sign the petition and learn more about the Nooksack River Wild and Scenic Campaign »

This article originally appeared in The Hill on July 19, 2018

Franklin Square, located in the heart of downtown Washington, is the District’s oldest protected park. It was set aside by the federal government in 1832 to protect a spring that supplied drinking water to the White House. Despite this protection, contaminated water continued to pose health risks for Washingtonians, including President Abraham Lincoln’s beloved son Willie, who died in the White House in 1862 from typhoid contracted from contaminated drinking water.

Today Washington’s drinking water is generally safe, but the recent drinking water advisory highlighted the vulnerabilities in our water systems locally and nationwide. This latest incident, resulting from a loss of pressure at a pumping station, along with reports of toxic algae outbreaks in drinking water sources from Oregon to Florida is a wake up call: We need to invest more in the nation’s water infrastructure, including our rivers, and we must uphold federal clean water safeguards.

The American Society of Civil Engineers gives the nation’s drinking water infrastructure a D grade. There are 240,000 water main breaks across the country each year, and 6 billion gallons of treated water are lost each year to leaking pipes. An estimated $105 billion is needed to upgrade our country’s drinking water and wastewater systems. We also need to protect and restore our rivers. Nationally, rivers provide much of our drinking water supplies. Healthy rivers, wetlands and floodplains are natural infrastructure, vital to our safety and economy.

While the quality of our nation’s drinking water remains high for the most part, there are still glaring outliers such as the lead contamination in the water supply for Flint, Michigan. Water warnings are popping up across the country this summer.

Salem, the capital of Oregon, was under an advisory for weeks in June because of a toxic algae outbreak in its water supply. Children under six years old, pregnant women, nursing mothers and adults with compromised immune systems were told not to drink the water. While there are multiple reasons for the algae outbreak, one likely cause is industrial logging practices and the resulting pollution from clearcutting, chemicals and fertilizers.

In Florida, algae from Lake Okeechobee is spurring concerns for human health, fisheries and the economy. Fueled by phosphorous and nitrogen in fertilizer running off farmlands, the algae can be toxic if consumed, causes skin and respiratory irritation, and can be fatal to dogs that swim in or drink the water.

The lesson from Oregon and Florida is clear: What we do to the land impacts our rivers and water supplies.

In Ohio, Gov. John Kasich (R) recently signed an executive order to toughen control of fertilizer pollution — an important step — stemming from the algae outbreak in Lake Erie in 2014 that left 500,000 people without drinking water for three days.

While state action is important, it is critical that we increase federal investment and preserve national clean water safeguards. In addition to supporting water infrastructure funding, Congress must uphold the Clean Water Rule, which protects small streams and wetlands — the drinking water sources for one in three Americans — from pollution.

As was recognized 186 years ago when Franklin Square was protected, water is life. It is essential to our health, our economy and our future. The warning signs this summer are a call to action for better clean water protections nationwide.

This guest blog was written by Andrew Whitehurst. It is a part of our blog series on America’s Most Endangered Rivers® – Pearl River. American Rivers listed the Pearl River as one of America’s Most Endangered Rivers® back in 2015 due to the threat of a proposed new dam and lake project.

What’s the deal with this project? Here’s some background.

After the devastating Easter flood of 1979, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was charged with developing a comprehensive flood control plan for Metro Jackson, Mississippi. Several Pearl River plans were introduced, focusing on flood control and environmental impact. They were never implemented due to public opposition, and concerns over funding and downstream impacts.

In 1996, a local businessman proposed the first of several plans to dam the river in Jackson below Ross Barnett Reservoir Dam to develop an urban waterfront with questionable flood control benefits. The proposal changed over the years in response to ineffective flood control designs, exorbitant costs, and environmental concerns.

Most recently, local sponsors (The Rankin-Hinds Pearl River Flood and Drainage Control District and the non-profit Pearl River Vision Foundation) published a Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) and Feasibility Study for a new dam and lake on July 24, 2018, with a 45-day public comment period ending September 6th.

A Flawed Plan

This project proposal is based on poor assumptions and incomplete information. “The plans incorporating economic development cost more than levees” (MS Legislature PEER Committee Report #540, p.34, 10/12/2010). In fact, the flood control plans developed before 1996 offer less costly options that better address flooding concerns. These options include improvements to existing levees, raising buildings and homes, or buying out properties with historical flooding problems. The Drainage District’s DEIS now claims levees cost more than a dam/lake alternative. The river hasn’t changed since 2010 and construction prices haven’t changed that much, so what’s going on here?

The lake dredging plan would bulldoze riverside forests, dredge and dig 25 million yards of riverbanks and river bottom to elevate 1861 acres and get it ready for lakeshore development. These wetlands along the river provide natural flood protection for our community. This plan goes against the national trend of dam removal and wetland protection.

A man poses with a sturgeon he caught in the Pearl River in 1944 before the construction of Barnett Dam. Now, this fish species is endangered. | Mississippi Museum of Natural Science Archives

Eliminating 10 miles of river habitat for two federally-protected species (Gulf sturgeon and ringed sawback turtle) will harm many types of wildlife and slow these species’ recovery. This much habitat destruction also adds needless expense to this purported flood control project.

The Pearl River is the fourth largest source of fresh water to the Gulf, east of the Mississippi River. The Pearl’s discharge from the upstream Ross Barnett Reservoir has reached critical low flow levels over the years with surprising frequency. Another dam will only complicate this problem.

In 2013, scoping comments asked the District for a hard look at Pearl River low flows June-October, which they continued to avoid addressing in this DEIS. Their approach hides monthly variability, softening a lake’s impact to the river. More sophisticated modeling should be run to see exactly how sensitive the lower Pearl River’s swamps, marshes and the western Mississippi Sound are to damming and to more complicated water management demands from a second major lake.

Further, the Draft EIS doesn’t address the effects of climate change in its modeling of the river and its physical functions. Hotter summers are predicted by scientific studies of the southeastern U.S., which means increased evaporation for all lakes, including this one.

BAD for Our Economy & Community

The Drainage District’s Draft EIS has an economic analysis that concentrates its cost/benefit analysis on Hinds and Rankin Counties. Downriver counties and parishes need cost/benefit analyses too.

- The area’s $891 million seafood industry supports 9,491 jobs (Mississippi State University Extension, 2/13/2018), and is reliant upon healthy freshwater flows.

- Hundreds of millions of dollars in restoration projects are underway or planned for coastal Mississippi and Louisiana, such as a $50 million marsh, oyster and living shoreline project.

- Water treatment costs are expected to increase for nearly 100 downstream Pearl River businesses and municipalities that rely on the Pearl for adequate dilution of their discharges, such as International Paper and Georgia-Pacific.

- Project proponents have been passing their upfront costs onto taxpayers – to date taxpayers have already paid $8 million for feasibility studies (MS Legislature PEER Committee Report #545, p.9, 12/14/2010).

- Increased property taxes in and around Jackson finance the project. Mississippi House Bill 1585 (2017) gave the Rankin-Hinds Pearl River Flood Control and Drainage District authority to tax property owners who are, “directly or indirectly benefitted by the project.”

- The Drainage District’s cost projections appear to oversimplify and undercut the expense of removing old hazardous waste sites and landfills along the river.

Furthermore, there are many unknown costs associated with the project, such as costs to relocate infrastructure (i.e. roads, bridges, railroad lines, utilities, landfills) that would be impacted, or costs to operate, manage and maintain the dam and lake. In addition, a detailed wetland mitigation plan is absent from the DEIS and so those costs are not final.

What’s Next

State and federal permits are still needed for this project, and 12 downstream stakeholders have passed resolutions against it. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is currently accepting public comment on the DEIS until September 6, 2018. You can make a difference today!

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/6408/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”4″ center=”yes”]Take Action »[/su_button]

Andrew Whitehurst is Gulf Restoration Network’s Water Program Director and works on water and wetland issues from Madison, MS.

This guest blog is by Tim Palmer, photographer and author of “Wild and Scenic Rivers: An American Legacy.”

When I need to brighten my day, I go to the river.

I walk along the shore, or sit for awhile at the water’s edge and listen to the swish, or the babble, or the exciting bubbly rush of flow. Always moving when the rest of the landscape is still, the river holds me rapt, and if I stare long enough, it mesmerizes and takes me away to a special place where the rest of the world — along with its eternal complications, everyday demands, and political disappointments — seems like a thousand miles away. And floating on the river is even better, drifting with the current wherever it goes.

Montana’s Flathead River was one of the original eight rivers to be protected under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. | Tim Palmer

Part of the appeal of rivers likely has an evolutionary context: our bodies are nearly 70 percent water, and every drop comes from a river or from groundwater, which is inseparably connected to the surface flow. Rivers are essential to our lives and communities, and they also create the finest of all wildlife habitat. Their free-flow from mountains to sea makes possible the iconic runs of salmon and steelhead in the Northwest, and of other fish throughout the nation.

Through the 1960s our natural rivers — and all of their attributes — were being lost at an astonishing rate by the construction of large dams. Some 70,000 had been built on virtually every major river, and hundreds more were proposed, planned or under construction regardless of their economic worthiness, their hydrologic capabilities to supply water, or their unintended but harmful effects on fish, wildlife, recreation and landowners.

Rising against this backdrop of gung-ho damming, Congress passed the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act in 1968 with unanimous support in the Senate and with a bipartisan 265-7 vote in the House. Seeking balance of federal policies that for a century had encouraged development at any cost, the law recognized that some of our finest natural streams should remain the way they are. The new law represented nothing less than a new way for a nation to regard its rivers, its landscape, and its environment.

For selected rivers, the program bans dams or other federal projects harmful to the streams, and it encourages other means of protection for fish, wildlife, water quality and historic values. Intending to go beyond the initial 8 designated rivers (12 counting major tributaries), the Act established protocols for adding rivers to the system.

Pennsylvania’s Delaware River had three different sections designated as Wild and Scenic. | Tim Palmer

Designation in this foremost program for river stewardship sets the stage for better management of recreation of all types. The resulting national prestige has also bolstered efforts to protect streamfront open space, to reinstate healthier flows in diverted sections of some rivers, to develop trails, and to reinforce local communities and economies.

Today, as we near the 50th anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, nearly 300 rivers have been set aside nationwide. That spells success, though among 2.9 million miles of rivers and streams in the nation, only 0.4 percent are safeguarded in this program.

The upcoming anniversary of the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act on October 2, 2018, is a cause to celebrate the legacy of all who have worked for the health of America’s finest streams. It also challenges us to do more. Perhaps most important, national recognition through this federal law — enacted half a century ago — can inspire all to engage further in ongoing efforts aimed at protecting and restoring these and other waterways.

Learn more about how we’re celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act by visiting 5000miles.org.

Tim Palmer is the author of Wild and Scenic Rivers: An American Legacy, which tells the lively history of river protection through this national program with 160 spectacular color photos. See this and Tim’s other work at www.timpalmer.org.

Collecting 1 million pounds of trash in a single day takes dedication. And people — 8,000 to be exact. Such huge numbers are why we are tipping our hats to the Ohio River Valley Water Sanitation Commission’s (ORSANCO) annual River Sweep event. Every June, River Sweep mobilizes volunteers to the Ohio River and its tributaries, fringed by 3,000 miles of river shoreline.

“It’s not our volunteers’ trash that they’re picking up,” says Lisa Cochran, who coordinates the event for ORSANCO. “But they are willing to come out and get dirty and take this responsibility on. They have special hearts.”

Photo by Jean Ison at the Ohio River sweep

Cochran describes the Ohio River as “everything a river can be.” It supplies local communities with transportation, drinking water, recreation, fishing, boating and beauty. “It’s part of the community here.”

Back when River Sweep first launched nearly 30 years ago, the Ohio—which is the lifeblood for six cities—was a dumping ground for large items like water heaters and cars. Though they no longer find appliances in the river, volunteers do have a new challenge: single-use plastics.

“You drop a pop bottle in the parking lot and think, ‘Oh well.’ You don’t think it’s going to make it down to the Ohio River. We get people out to River Sweep because, just like American Rivers says, when you connect people to rivers, they protect rivers.”

For information about a river cleanup near you, visit www.AmericanRivers.org/Cleanup.

Rivers are in the spotlight in Denver at the Outdoor Retailer Summer Market, North America’s largest tradeshow in the outdoor industry.

Numerous events, discussions and parties throughout the show, from July 22 – July 25 are focused on the importance of clean water and healthy rivers to businesses and communities.

And it’s a big deal: The Colorado River alone supports a $1.4 trillion economy each year, including recreation, agriculture, power and water supplies.

Across the country, rivers provide much of our clean, safe, reliable drinking water, and every year Americans spend $86 billion on watersports.

Another reason everyone’s talking about rivers? This year is the 50th anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act – the landmark law that permanently protects rivers with outstanding scenic, recreational, fish and wildlife, historic and cultural values. Like America’s National Parks, wildlife refuges and wilderness areas, the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System was the first of its kind in the world.

A coalition of conservation organizations and leaders in the outdoor industry have joined forces to celebrate the anniversary and advance the next 50 years of river protection in our country. The campaign, 5,000 Miles of Wild® – is a campaign of American Rivers, American Whitewater, NRS, OARS, YETI, REI, Chacos, NiteIze, Chums, Keen, Kokatat and Yakima. We’re working together to protect 5,000 new miles of Wild and Scenic Rivers and one million acres of public land over the next two years.

“In an era when public lands and clean, healthy waters – concepts we once took for granted in America – face grave threats, we must renew our commitment as a nation to protecting free-flowing rivers and wild places for generations to come,” said Mark Deming, NRS Director of Marketing.

“5,000 Miles of Wild brings us together to protect something vital to our everyday lives, and vital to our outdoor lifestyles and recreation,” said Colleen Gilligan, Director of Marketing at Chums.

“We want our children and children’s children to have the same opportunity to enjoy our amazing natural resources that we had. We want them to build the same memories and love for the outdoors that we did. The more we can come together as an industry and advocate for the outdoors, the more we can protect and save these opportunities for everyone.”

During the Outdoor Retailer Summer Market, Boulder-based company NiteIze is throwing a party to rally attendees in support of Wild and Scenic Rivers, and NRS, Chums and American Whitewater are hosting events to celebrate rivers and drive action for river protection.

Upon signing the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act on October 2, 1968, President Lyndon Johnson said, “Every individual and every family should get to know at least one river.”

We couldn’t agree more, and we are grateful to our partners in the outdoor industry who are stepping up to ensure a future of healthy rivers for all.

Join our 5,000 Miles of Wild campaign to support Wild and Scenic River protection, and if you’re heading to Outdoor Retailer, we’ll see you at the many river-themed events throughout the show!

In today’s guest blog Steve Evans of Cal Wild and Friends of the River writes about the State of California protecting the Mokelumne River as the state’s newest Wild and Scenic River. For the past 30 years the Foothills Conservancy and Friends of the River have fought to defend and protect the “Moke” and led the successful Wild and Scenic effort despite near continuous fights over water in California. With 2018 marking the 50th Anniversary of the national Wild and Scenic Rivers Act and over 1,100 miles of new Wild and Scenic designations pending in Congress we hope that this is just the beginning. www.5000miles.org

The Mokelumne River became California’s newest Wild and Scenic River when Governor Jerry Brown signed the natural resources budget bill in the last week of June 2018. Protection of 37 miles of this magnificent river in the Sierra Nevada foothills – from Salt Springs Dam to a point just upstream of Highway 49 – became a reality after decades of advocacy by Friends of the River, Foothill Conservancy and other conservation groups. The unusual legislative vehicle used to protect the river – the natural resources budget trailer bill – became possible due to a rare consensus between conservation groups, water agencies and the California Natural Resources Agency (CNRA).

In response to 2016 legislation authored by Assembly member Frank Bigelow (R-O’Neils), the CNRA conducted a study to determine the Mokelumne’s eligibility and suitability to be protected as a state wild and scenic river. Released in early 2018, the study found the river to be free flowing to possess extraordinary scenic and recreation values. More than 1,700 people responded positively to the draft study’s conclusion that the river was suitable for state protection. The final report proposed special language to ensure that state designation did not affect existing water rights and facilities and that future additional rights to water from the Mokelumne could be acquired for projects that avoided harm to the river’s flow and extraordinary values.

Representatives from Friends of the River and the Foothill Conservancy worked out the language with water agencies from Amador and Calaveras Counties, East Bay Municipal Utility District (EBMUD), and the CNRA. In response, the local foothill water agencies withdrew their long-standing opposition and formally supported wild and scenic protection for the Moke.

“It took several years to reach agreement to protect the Mokelumne River for present and future generations,” stated Eric Wesselman, Executive Director of Friends of the River. “But with some persistence, we eventually developed the political consensus needed to protect this magnificent river in the Sierra Nevada foothills,” he said.

“This is a landmark achievement,” said Scott Ratterman, Calaveras County Water District Board president. “We are proud to have reached a consensus with all stakeholders that protects local water rights and the river for future generations.”

The support of the local water agencies neutralized opposition from local supervisors in Amador and Calaveras counties. EBMUD, which delivers clean drinking water from the Mokelumne to 1.4 million customers in the east Bay Area, has supported wild and scenic protection for the river since 2015.

The turn-around in the river’s political fortunes was dramatic. The foothill water agencies managed to block passage of 2015 bill by Senator Loni Hancock (D-Berkeley) that would have added the river to the state wild and scenic rivers system. Ironically, the Hancock bill included water rights assurance language similar to the special language worked out with the CNRA and subsequently included in the budget trailer bill.

The Mokelumne is the seventh river protected as a state wild and scenic since the system was established in 1972. California wild and scenic rivers are protected against destructive dams and diversion projects and state agencies are required to protect the rivers’ free flowing character and extraordinary scenic, recreation, fish and wildlife values. Friends of the River played a key role in adding rivers to the state system since 1986.

Since 1988, Friends of the River and the Foothill Conservancy have worked together with their conservation allies to protect and restore the Mokelumne River. The groups advocated for federal wild and scenic river protection through land and resource plans by the U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management. They secured improved flows and recreational access through the federal relicensing process for PG&E’s extensive hydroelectric facilities on the river. They successfully pressured EBMUD to restore public recreational access to the river downstream of Highway 49. Along the way, three dam projects were shelved due to opposition by conservation groups. Now, 37 miles of the river are permanently protected by the state.

The newly protected segments of the Mokelumne River represent an important recreational resource for residents of Amador and Calaveras counties and their tourism-based economies. Protection of the river was a long-time priority of the locally-based Foothill Conservancy and other local conservationists.

“I can’t begin to tell you how happy we are,” said Katherine Evatt, board president of the Foothill Conservancy. “It’s a tremendous day for our community. People really love the Mokelumne. We have worked for decades to ensure that this beautiful river is protected for generations to come, and finally, the upper Mokelumne is a California Wild and Scenic River.”

Author: Steve Evans

Steve Evans was hired by Friends of the River in 1988 and has served as Conservation Director from 1990 until June 1, 2011. He has more than 35 years of conservation policy experience in public lands and resource issues. He successfully encouraged federal agencies to identify more than 3,000 miles potential Wild & Scenic Rivers and has played a key role in the legislative expansion of the federal and state Wild & Scenic Rivers Systems in California.

This is a guest blog by Gregory Fitz and Dakota Goodman.

In October of 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act into law. The legislation had been sponsored in Congress by Senator Frank Church of Idaho. The National Wild and Scenic Rivers system was conceived around the remarkable idea that some rivers were so valuable to the cultural and environmental legacy of a region that they, and some of their surrounding area, should be preserved as natural, free-flowing waterways for the benefit and enjoyment of future generations. Since then, almost 13,000 miles of 208 rivers across the country have been protected. Six of those rivers are in Washington.

To celebrate the 50th anniversary of the National Wild and Scenic River Act, we’re going to spend some time over the course the year telling the stories of Washington’s designated rivers: Illabot Creek, the Klickitat River, the Pratt River, the Skagit River, the White Salmon River and the Middle Fork of the Snoqualmie River. Each is a unique part of Washington’s astounding network of rivers and each earned its designation in the national system through the hard work and foresight of advocates.

We’ll begin with the White Salmon River, one of the initial rivers in Washington to earn the National Wild and Scenic River designation.

The White Salmon River

The White Salmon River originates among the glaciers and snowpack of Mount Adams. It flows South 44 miles to join the Columbia River an hour’s drive east of Portland, Oregon. Its watershed encompasses approximately 400-square miles. It is a tumbling, fast moving river that flows through a long, vertical wall gorge and contains a series of Class III-V rapids, placing it among the most popular whitewater rafting and kayaking rivers in the Columbia River basin, with many expert paddlers flocking to the lower gorge, challenging even the most experienced boaters.

The river supports a healthy population of rainbow trout. Historically, it also supported substantial runs of steelhead, coho salmon, and fall and spring Chinook salmon. The construction of Condit Dam in 1913 blocked those migratory species. When the dam was breached in 2011, salmon and steelhead were able to reach upstream spawning habitat for the first time in nearly one hundred years. Standing 125 feet tall, Condit Dam was the largest dam removed in the United States until both Elwha River dams were knocked down a couple years later.

The White Salmon River flows through the ancestral territory of the Klickitat People. They are a Shahaptian tribe and many are currently enrolled members of the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation. The Klickitat People encountered Lewis and Clark’s expedition in 1805.

National Wild and Scenic Rivers Designation

Two sections of the White Salmon River have been set aside as part of the National Wild and Scenic Rivers system. The first, lower reach, begins at the confluence with Gilmer Creek, near the town of B Z Corner, and runs to the confluence with Buck Creek. It was designated in 1986. The second, upper reach, runs from the headwaters to the boundary of Gifford Pinchot National Forest and includes Cascade Creek from its headwaters to its confluence with the White Salmon. This second reach was designated in 2005. The two sections represent 27.7 miles of the White Salmon River, but they are not contiguous.

Condit Dam had been built in 1913 and by the 1970s, seven additional dam projects were being proposed along the White Salmon. Advocates feared these dams would bury the river’s dynamic character and bedrock geology underneath endless acres of reservoir water. A passionate group of volunteer advocates formed the Friends of the White Salmon River and worked tirelessly to prevent the proposed dams. Fortunately, they were successful, but their advocacy didn’t end when the dams were stopped.

A broad coalition of local residents, business owners, environmentalists and management officials began to push for the White Salmon to be included in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. The pointed to the water quality, basalt gorge, timber resources, whitewater recreation, a Native American longhouse and cemetery and the potential to restore anadromous fish populations as reasons for its protection. The opportunity arrived in 1986 when the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area Act was signed by President Reagan. Because the confluence of the Columbia River and White Salmon River is within that designated area, it made perfect sense to also designate the lower reach of the White Salmon as a National Wild and Scenic River.

Steve Stuckmeyer and Megi Morishita drop into the White Salmon Narrows below Condit Dam on the White Salmon River. Photo by Thomas O’Keefe.

After the designation of the lower reach, the broad coalition of advocates kept working. They pushed for the additional designation of the headwaters to preserve the White Salmon’s unique geology, steady flow of cold, clean water and native fish habitat. Partnering with managers in Washington and the U.S. Forest Service, they were eventually able to get the upper reach added to the Wild and Scenic Rivers National System in 2005.

Simultaneously, many of the advocates were working to breach Condit Dam. After many false starts and intense dialog between government agencies, local communities and the power company that owned the dam, this would happen only a few years later.

The Wild and Scenic White Salmon River: Today

Due to its consistent flow and steep gradient, thousands of boaters race along the White Salmon’s rapids, waterfalls and gorge every year. The removal of Condit Dam added five miles of additional river to run. This recreational traffic supports a robust tourist economy and provides visitors a thrilling opportunity to experience an aggressive Washington river in its glory.

As the rafters and kayakers head downstream, native fish are swimming upriver again. Researchers are finding steelhead and salmon spawning in the site of the old reservoir and, especially, on the headwater gravel and tributaries protected and preserved by the Wild and Scenic River designation. With a bit of luck, their numbers will continue to grow as the fish continue to take advantage of protections provided by this important legislation.

Next month, we’ll be profiling the Klickitat River, another one of the six Wild & Scenic designated rivers in Washington.

In celebration of the 50th Anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, we have teamed up with a number of partners and outdoor gear companies to collect 5,000 wild-river stories and to protect 5,000 more miles of such rivers nationwide. Share your story and learn more.

This guest blog from Jill Crafton is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series on the Mississippi River Gorge.

As residents of the Upper Mississippi River Basin, we often take for granted the natural ecosystems that exist within the basin. The meandering river, floodplains and tributaries define its character and support the many birds, mammals, reptiles and amphibians and species of fish throughout the channels and backwaters. The Upper Mississippi River Refuge Act establishing the Mississippi River Wildlife and Fish Refuge was passed on June 7, 1924 to preserve the natural character of this 300 mile river bottom preserve.

In 1922, fifty-four Mississippi River anglers formed the Izaak Walton League in response to the loss of wilderness and pollution of our rivers that, at the time, were used as sewer systems. The first aggressive action was to protect the Mississippi River system. The great conservationist Will Dilg led this effort by proposing the Upper Mississippi River Refuge Act to protect the river. Dilg and the Izaak Walton League brought about the appropriation, establishment and management of this preserve through Congress in 1924 to address the pollution, erosion damage due to siltation, and the disappearing fast waters and spawning habitat.

Later in 1930, Congress authorized the “construction and repair of the river” which led to the creation of the nine-foot navigation channel. Realizing that the nine-foot channel, which flooded thousands of acres of forest and wildlife habitat during construction, was inevitable, members of the Izaak Walton League joined by women of the Federation of Women’s Clubs attended hearings from 1930 – 1933. The thrust of their opposition was to secure agreement to maintain relatively stable water levels and to assure the full consideration of protection for recreational and aquatic values. The Izaak Walton remains a relentless advocate for the river’s habitat for fish and mammals and the aquatic plant life that migrating birds need for food.

Since the Refuge’s establishment, a series of dams — the nine-foot navigational channel — and sewage pollution have compromised its wilderness, wildlife habitat and natural beauty by disrupting the natural flows of the river and destroying habitat for fish and wildlife. Keeping the dams in place requires continued costly maintenance and operation of the Locks and Dams; moreover, maintenance is backlogged, and there are a finite amount of dollars available. In the Mississippi River Gorge below St. Anthony Falls there is an exciting opportunity to restore the natural flow and character of the river and influence the future of this stretch of the river.

Next week, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers will host public meetings on the Disposition Study that will guide the fate of these two upper most dams that are part of the nine-foot navigation channel project. Removing the dams to restore fish and wildlife habitat is an option and can be accomplished a few ways.

- The Corps could release the dams to another owner who would remove them. Under this model, local non-profits and/or citizens could create a limited liability trust that would raise the funds necessary to remove the infrastructure and oversee the project. Similarly, a municipality, like a park district, could take ownership of the infrastructure and remove the dams.

- The Corps could keep the dams and evaluate their removal through existing authorities. There are two authorities that the Corps uses to remove dams and restore aquatic ecosystems:

- Section 1135 of WRDA 1986, the Corps’ first ecosystem restoration authority, authorizes modifications of Corps projects to improve the environment, and

- Section 206 of WRDA 1996 authorizes the Corps to carry out aquatic ecosystem restoration projects to improve the quality of the environment on sites unrelated to Corps projects.

Both of these options have pros and cons. If the dams are released and removed through another entity, removal will be certain and swift. But this option is expensive and fundraising through foundation grants and private donors might compete with other important local projects. If the Corps keeps the dams and pursues removal through their authorities, removal and restoration would take longer and success would be less certain. The projects would compete nationally for funding and be subject to political horse-trading. Additionally, local groups would still have to raise a portion of funds to match federal cost-share rules.

Either way, it’s important for everyone to get involved. Let the Corps know you want the dams removed by sending them an email or attend an upcoming public meeting if you are in the area.

Public meeting schedule:

July 16th at 6PM at Mill City Commons, 704 Second St. S., Minneapolis, MN 55401

July 17th at 6PM at Highland Park Senior High School auditorium, 1015 Snelling Ave S, Saint Paul, MN 55116

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/4987/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”4″ center=”yes”]Take Action »[/su_button]

Author: Jill Crafton

Jill Crafton, Izaak Walton League. Jill is on the Board of Directors for the Izaak Walton League of America and lives in Bloomington, MN. She serves on several committees committed to improving the water quality of the Great Lakes and Mississippi River and sits on the Riley Purgatory Bluff Creek Watershed District Board.

Jill Crafton, Izaak Walton League. Jill is on the Board of Directors for the Izaak Walton League of America and lives in Bloomington, MN. She serves on several committees committed to improving the water quality of the Great Lakes and Mississippi River and sits on the Riley Purgatory Bluff Creek Watershed District Board.

Summer has been hot already – heck, it’s July – it’s supposed to be hot!

But in my neck of the woods, it has been particularly smoky as well. As I sit here in my office in Durango, a campfire-like aroma permeates everything as the 416 fire, which started more than a month ago, continues to burn across more than 55,000 acres of forest, increasing daily. Thankfully, recent rains have helped stifle fire activity and this particular fire is no longer considered a threat.

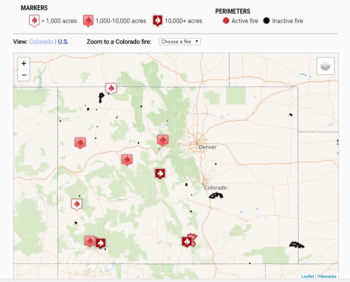

Map of Colorado’s wildfires as of 7/11/2018, courtesy of The Denver Post. (Click to be directed to the map.)

Last winter, Colorado received only about two-thirds of the snowpack we normally get, especially in the Southwestern corner of the state, where both the Rio Grande and San Juan river basins had less than half what we normally receive. Less snow equals less spring and summer river flows, and the Animas through Durango is a perfect example. On the day of its peak runoff, the Animas had less than 25% of its normal flow through town, a river of sorrows for sure. Couple that with an extremely dry spring (La Plata County had less than one-sixth of its normal spring precipitation) and the formula for explosive wildfires was set. Over the course of the winter, conversations in the local post offices and watering holes about the statewide lack of snowpack resulting in an aggressive fire season were frequent – and it appears those fears are coming true. Now, maps of western Colorado are dotted by little flame symbols from the northwest corner of the state in Moffat County to south-central Colorado where the wildfire on La Veta pass is raging. Basalt has one, Silverthorne, Fairplay, Norwood, Dolores – this smoke will linger until the monsoons kick into gear (we hope…)

Here in Durango, the fire’s impact to the local economy was instantaneous, as the normal influx of tourists from across the country diverted their plans and went elsewhere. In the local fly fishing shop, Duranglers, reservations for guided trips is down considerably, and the rafting outfitters were cut off from the river for more than two weeks, curtailing one of the most productive periods of the year – runoff in the Upper Animas River. Hotel and supermarket parking lots have noticeably more spaces available than normal for this time of year, and it is pretty easy to get a seat in one of our fabulous local restaurants. With the amazing fire crews gaining more control over the blaze, town is bustling, the train is running, and other than the thick brown haze outside my office window, things are getting back to normal. But it was certainly tense around here for a while.

Rain dances only work so often, and there is no reliable way to make more snow in the winter, how we manage the water we do get is something that each of us can control. Earlier this year, we released a report called Do You Know Your Water, Colorado, which outlines how Colorado’s rivers, streams, and population are inherently tied together – from the western slope where roughly 80% of the state’s water falls from the sky as snow, forming a welcome snowpack, to the eastern slope where more than 80% of the population lives. We describe how water moves around the state, supporting both a thriving population base as well as a vibrant economy that includes outdoor recreation, farming and ranching, and a multitude of jobs all across the state. And as important as it is for each of us to do what we can to stretch our water supplies as far as we can, understanding how the system works is key to taking action on behalf of Colorado’s rivers. Check it out!

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act – a landmark law protecting outstanding, free-flowing rivers nationwide. As part of our celebration of this milestone, today we are releasing a new film, 5,000 Miles of Wild.

Combining stunning scenery with insightful commentary on the state of river conservation from Senator Tom Udall, Ted Roosevelt IV, American Rivers President Bob Irvin, Rio Grande Riverkeeper Jen Pelz, river guide Austin Alvarado and others, this film is a powerful call to action for protecting our country’s remaining wild rivers for future generations.

5000 Miles of Wild from American Rivers on Vimeo.

The film was shot earlier this year by filmmaker Ben Masters during a trip on the Wild and Scenic Rio Grande in Big Bend National Park. A New Yorker story, published in May, captures some “behind the scenes” of the film shoot and details the issues facing the river.

It was an honor to have Senator Udall from New Mexico with us on the trip. In the film, he talks about his his father Stewart Udall, who was Secretary of the Interior under President Johnson, and integral to creating the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. Ted Roosevelt IV, whose great-grandfather was the 26th President of the United States, shares his perspective on our nation’s conservation history and advice for today’s river advocates.

We want this film to broaden awareness about the importance of protecting wild rivers, and spark positive action: viewers can visit www.5000miles.org to sign a petition supporting protection of 5,000 new miles of Wild and Scenic Rivers nationwide.

There are a million reasons why we need more Wild and Scenic Rivers. To see some examples, read through the personal stories shared on the 5,000 Miles of Wild site, then share your own.

“We need to be doing more, not less, to protect the rivers that give us clean drinking water, unsurpassed recreation opportunities, fish and wildlife habitat, and connections to culture and our shared heritage,” says David Moryc, Senior Director of River Protection for American Rivers.

“Together with our partners and supporters, we are advancing vision for the next 50 years of river protection in our country.”

The official anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act is October 2, 2018.

This guest blog from Mike Davis is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series on the Mississippi River Gorge.

“The channel was very crooked, winding about between reefs of solid rock, with an eight to ten mile current… he knew that the drift of a minute in that white water would pile us up on the next reef below… for the next six miles he turned and twisted among the reefs, under a full head of steam, which was necessary to give us steerageway in such a current.”

– From “Old Times on the Upper Mississippi” by George Merrick

Although this does not sound like a description of any river channel within the Twin Cites, Minnesota, it is.

Only a century ago, the reach of the Mississippi River downstream of St. Anthony Falls met this description. Depending on the season, a raging white-water torrent or a more docile rapids and riffle channel flowed around a dozen or more islands on the way to its confluence with the Minnesota River. Early explorers remarked often about the majesty of the falls, and were amazed by the huge numbers of eagles and other fish-eating birds that congregated in the gorge below to feed. This was no accident since the rapids below the falls was one of only three that existed upstream of St. Louis. With the falls blocking further upstream movements, the rapids area of the Mississippi’s only gorge was no doubt a destination for both migratory and resident rock-loving fish species. Although historic accounts lack detail, it is probable that this rapids was a critical spawning habitat for several large river fish species, such as sturgeon and paddlefish. Today the rapids are “lost” beneath the impoundment created by the Ford Dam.

Historically the Mississippi River between St. Anthony Falls and Lake Pepin (68 river miles) supported at least 43 species of native mussels. Native freshwater mussels have been integral players in river ecology for millions of years. Mussels feed on bacteria and fungi that they filter from the river water, stabilize the riverbed with their shells and provide attachment and habitat for other life ranging from algae to walleye. They are unique among the world’s mollusks in having a parasitic life stage using fish as temporary hosts. Numerous fascinating adaptations of females deliver larvae onto the fish species of choice.

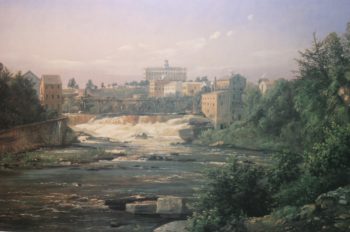

Painting of the Mississippi Gorge | Minnesota Historical Society

Once so abundant that the river bottom was literally made of mussels, by 1900 water quality in this reach of the Mississippi River had declined enough to nearly eliminate them. Giant floating bogs of rotting sewage sucked the life-giving oxygen out of the water for decades. These degraded conditions continued until the 1970s when Congress passed, and President Nixon signed, the Clean Water Act. Water quality improved during the 1980s and 1990s with the separation of sanitary and storm sewers in the Twin Cities Metropolitan area and wastewater treatment was much improved.

Today, both native fish and mussels are again thriving in this reach of the river. However, 20 species of native mussels have yet to recolonize this improved habitat. In order for this to occur, host fish carrying mussel larvae must travel from a part of the river still supporting these species – travel greatly impeded by dams today.

With large river species of fish far below their reported historic abundances and with spawning rapids obliterated elsewhere on the Mississippi below the falls, restoration of these rapids and access to them by migrating fish would be an enormously important ecological achievement. A modern-day redemption for the uses conceived of at the close of the 1800s, but still with us today.

Below the Mississippi Gorge falls | BF Upton

Moreover, with the recent return of good water quality, restoration would create recreational and scenic opportunities not found in a large urban setting anywhere else in the U.S. Redemption of these rapids would create 2 to 300 acres of accessible riparian parklands and 15 miles or more of high quality shoreline angling opportunities.

Kayaking anyone?

You can help us Restore the Gorge! If you are in the area, attend a public meeting:

July 16th at 6PM at Mill City Commons, 704 Second St. S., Minneapolis, MN 55401

July 17th at 6PM at Highland Park Senior High School auditorium, 1015 Snelling Ave S, Saint Paul, MN 55116

[su_button url=”https://act.americanrivers.org/page/4987/action/1″ background=”#ef8c2d” size=”4″ center=”yes”]Take Action »[/su_button]

Author: Mike Davis

Author: Mike Davis

Mike Davis is a River Ecologist.