This blog post was written by Melissa Youssef, current City Councilor and Mayor Pro Tem for the City of Durango. Join us to learn more about Durango’s connection with the Animas River.

My home town of Durango, nestled in a beautiful mountain valley in the southwest corner of Colorado, is a quintessential mountain town with an iconic river running through it. The 126-mile long Animas River descends from its headwaters high in the rugged San Juan Mountains before passing through Durango on its journey to meet the San Juan River in New Mexico. We have almost 8 miles of river frontage flowing right through the heart of town – which is why the Animas River is called the ‘spine of Durango.’ It is also, in many ways, the heart and soul of our town.

My family moved to Durango in 1997; my three kids grew up swimming, kayaking and playing on the beaches of the Animas River. I enjoy standup paddle-boarding, and like many residents of Durango, I also regularly walk and run on the Animas River Trail. All of us love the views we have of the river from our hikes on the mountaintops surrounding Durango, and recently, many of us had the pleasure of seeing a young bull elk standing attentively in the middle of the river right in the center of downtown. The Animas is the place we go for peace and tranquility and to escape the clatter and chatter that can take over our lives. For me, and for countless others, it is a sanctuary… even a church.

Fishing on the Animas River | Photo by Sinjin Eberle

The Animas has been an essential part of the colorful history of Durango. However, there were decades when our community neither understood nor recognized the importance of preserving and protecting this valuable asset, and instead turned its back on the river. All that has changed recently with the growth of Durango’s thriving commercial river rafting industry and the increasing popularity of river sports in general. Local government and business interests have acknowledged the positive economic impact the outdoor recreation industry has on our community. We began investing in our river, realizing not only what a huge asset the Animas is in terms of ambiance, character and local lifestyle – but also that it is an enormous economic driver in our tourism-based economy.

In response to heavy recreational use of the river, the City of Durango adopted the Durango Animas River Corridor Management Plan to develop and promote the river’s health, accessibility, in-stream recreational amenities, water quality, habitat protection and bank restoration. The Plan included an extensive community engagement process and encouraged residents to get involved with stewardship of the river.

The Plan did not address how to pay for these improvements, but they have been funded through a dedicated parks and recreation sales tax. In addition to the river improvements and other parks and recreation projects, the dedicated sales tax has funded the construction of 7.5 miles of the Animas River Trail, where community members are now able to enjoy the river while biking, jogging, skating, strolling or sitting on benches at lookout points all along the river. The Animas River Trail is by far the most used and enjoyed trail in our community.

But then…a heartbreaking setback…In August of 2015, sludge-filled water that had long been trapped inside the abandoned Gold King Mine north of Durango broke loose and 3 million gallons of toxic mine waste contaminated the Animas River, changing its color from emerald green to a surreal burnt orange. It was an environmental catastrophe, with massive impact to our outdoor recreation businesses, tourism, and community at large.

My family, like many families in Durango who love the river, felt personally devastated. National and international news reports and photographs of our foul orange river drew attention all around the world. The Animas was closed to the public for a period of time, and our community grieved. But we recovered, and the river clawed its way back to health. But then sadly, the river faced an ugly new challenge this past June when the 416 forest fire burned 55,000 acres of the San Juan National Forest north of town. Heavy rains following the fire washed ash and debris from the burn scar into the Animas, turning it black and suffocating thousands of fish.

These events have provided jarring wake up calls for us to be even more decisive and proactive in taking care of our river. We will never again turn our backs on the Animas. As the saying goes, “Water is the new gold.” Our river is an incalculably valuable resource and well worth our investments in time, energy, education and money.

Join us for Episode 2 of Ripple Effects, as we explore the connection the City of Durango has with their local river, the Animas.

Stroud Water Research Center presented the 2018 Stroud Award for Freshwater Excellence to American Rivers and our president and CEO, Bob Irvin, at the Stroud Center’s premiere fundraising gala, The Water’s Edge, yesterday evening.

“It is a great honor to receive this award from the Stroud Center,” Irvin said. “This award is for all of our generous members and supporters who make our work possible. At American Rivers, we believe every person in the country should have clean water and a healthy river and our supporters are moving us closer to achieving that goal.”

Since its inception in 2003, The Water’s Edge has featured an impressive list of individuals who have made noteworthy contributions to the world of science, fresh water, and conservation. Previous award recipients have included His Serene Highness Prince Albert II of Monaco; National Park Service and its director, Jonathan Jarvis; Alexandra Cousteau; Robert F. Kennedy Jr.; Dr. Jane Lubchenco and Dr. Kathryn Sullivan, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; Dr. John Briscoe; and Olivia Newton-John and John Easterling.

Reflecting on his more than thirty years in conservation, Bob said, “Of all the work I’ve done in my career, working to protect and restore rivers is the most hopeful work I have done.”

“No matter what we have done to a river, dammed it, diverted its flow, or dumped pollution into it, the river is still there. If we are wise enough to take out the dams, restore the flows, and stop polluting our rivers, they will come back to health amazingly quickly. I have seen it all across this country.”

Join American Rivers today: Your donation helps us continue our powerful advocacy to protect wild rivers, restore damaged rivers and conserve clean water for people and nature.

Business leaders, community advocates, and Congressional champions for Wild and Scenic Rivers from all over the country filled REI’s flagship store near the U.S. Capitol in Washington D.C. on Wednesday night to celebrate free-flowing rivers and call on Congress take action and pass the pending Wild and Scenic bills before the end of the year.

Senator Wyden speaking about his Oregon Wildlands Act.

The event builds on the momentum created across the country by the recent 50th anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act for new Wild and Scenic designations for rivers such as the Hoh on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula, the Nashua in Massachusetts, the Gila in New Mexico and the Molalla in Oregon.

We were fortunate to have such a strong turnout from members of Congress. Senators Maria Cantwell of Washington, Tom Udall of New Mexico, Ron Wyden of Oregon, and U.S. Representatives Don McEachin of Virginia and Kurt Schrader of Oregon shared their river stories and their support for Wild and Scenic Rivers.

American Rivers President Bob Irvin, Congressman Donald McEachin and REI Foundation President Marc Berejka.

Senator Cantwell, the ranking member of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee which is in charge of Wild and Scenic River designations, talked about the beloved Wild and Scenic Skagit River and her work to protect the Wild and Scenic Upper White Salmon River. Senator Wyden, who has championed more Wild and Scenic Rivers than any other member of Congress, stressed the value of river conservation for recreation and Oregon’s economy. Senator Udall recalled his trip on the Rio Grande, featured in the film 5,000 Miles of Wild. He talked passionately about his deep connection to wild rivers and wild places and the need to work with local stakeholders to permanently protect the Gila River.

Senator Cantwell pictured with REI’s Marc Berejka, American Whitewater’s Tom O’Keefe, Pew Trust’s John Gilroy, and American Rivers’ Chris Williams.

Outdoor industry leader REI hosted the event and has been a major supporter of Wild and Scenic River conservation. Other outdoor brands were at the event in full force. NRS, KEEN Footwear, Arcteryx and others are in town with the Conservation Alliance to lobby on behalf of Wild and Scenic River and other public lands bills. Fittingly, even the beer at the event had a Wild and Scenic connection as Deschutes Brewery — named for the famous Wild and Scenic Deschutes River in central Oregon — generously provided beer for the evening.

NRS Marketing Director Mark Deming talks with Jim Bradley of American Rivers and Senator Tom Udall.

The bills currently pending in Congress that include new Wild and Scenic River protections total over 1,000 miles and 350,000 acres of riverside lands and include the Oregon Wildlands Act and the Wild Olympics.

All of these bills are a part of the campaign to protect 5,000 miles of new Wild and Scenic River protections and 1,000,000 acres of riverside land and build a nationwide coalition of local groups and businesses to advocate for free-flowing rivers by October 2, 2020. The campaign business partners include REI, NRS, YETI Coolers, OARS Outfitters, Chaco, Nite Ize and KEEN Footwear and non-profit partners American Rivers, American Whitewater, Idaho Rivers United, and Pacific Rivers. With the designation of East Rosebud Creek in Montana in August we’re already on our way! You can become a part of the campaign too by going to www.5000miles.org to tell your river story and take action.

There were plenty of river wins to celebrate in 2018. From streams protected to dams torn down, here are a few big wins we can all be proud of (and thankful for).

- Federal court upheld the Clean Water Rule

American Rivers won a huge victory in our lawsuit challenging the Trump administration’s attempt to suspend the Clean Water Rule. A federal district court in South Carolina issued a nationwide injunction blocking the suspension on the grounds that the administration failed to comply with the law. As a result, the Clean Water Rule is now in effect in 26 states. The administration is appealing the decision, so our work is not finished. But our victory means that this administration, like any other, must comply with the law.

- East Rosebud Creek became Montana’s fifth Wild and Scenic River

As we celebrated the 50th anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act in 2018, Montana’s East Rosebud Creek became our nation’s newest Wild and Scenic River. The campaign to protect East Rosebud began in 2009, when a Bozeman-based hydro company applied for a permit to build a 100-foot-wide diversion dam just below East Rosebud Lake. American Rivers and our conservation partners filed formal objections and eventually convinced the company to abandon the project. We then joined with local ranchers and landowners to advocate for permanent federal protection. Our collective efforts paid off: 20 miles of this beautiful alpine trout stream will remain free-flowing forever.

- Colorado’s wild Maroon and Castle creeks protected

American Rivers reached a final agreement with the city of Aspen to permanently abandon plans to dam Maroon and Castle creeks. We worked with conservation partners, Aspen’s mayor and city officials to find a practical alternative to provide additional water should the city need it in the future. In addition to protecting two wild streams, the agreement also safeguards the iconic Maroon Bells-Snowmass Wilderness Area — one of Colorado’s most beautiful and photographed mountain valleys.

- Bloede Dam blast freed Maryland’s Patapsco River

Conservation leaders, federal and state officials and our other partners gathered to celebrate when explosives breached Bloede Dam. In 75 years, the nonfunctioning Bloede Dam caused at least nine drowning deaths and blocked migratory fish swimming to and from the Chesapeake Bay. Its removal is the linchpin of a decades-long restoration effort to restore 65 miles of spawning habitat to blueback herring, alewife, American shad and hickory shad.

- Alabama’s Coosa River put on the path to recovery

A federal court unanimously ruled in our favor and tossed out the license for seven harmful hydroelectric dams on the Coosa River. Construction and operation of the dams wiped out more than 30 freshwater species on the Coosa, which was once one of the most biodiverse rivers in the world. If left in place, the dam licenses would have been in place for the next 30 years. Now the Coosa’s remaining fish, mussel and snail species may have a shot at recovery.

Thank you to all of the local river groups, communities, conservation allies and supporters who made these victories possible in 2018. We are grateful for your partnership and look forward to even more action for rivers in the year ahead!

Sign up to stay in the loop on other river success stories, and how you can help.

It’s a fact of life in the Colorado River Basin that no one is really in charge.

Instead, the complicated business of managing the basin’s water supply is achieved collaboratively by an array of federal and state agencies, quasi-agencies, irrigation districts, cities, Native American nations and the Republic of Mexico — all operating according to a complex set of rules called the Law of the River. It’s a cumbersome machine that’s challenged to respond quickly to crises, even the slow-burning kind.

And yet, as John Fleck wrote in his book “Water is for Fighting Over,” the Colorado River Basin’s complex web of collaborations is perhaps the strongest asset as the people and agencies tasked with managing the river’s water supply face an uncertain and daunting future in the Southwest.

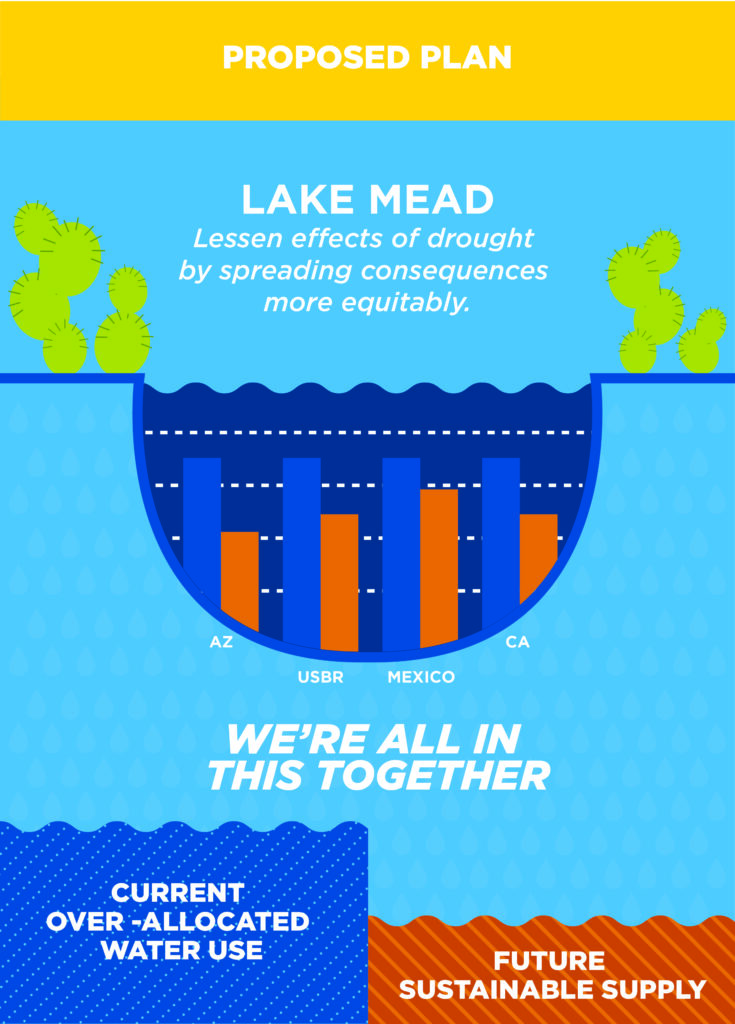

As we tend to say around the American Rivers’ watercooler, the best response to uncertainty is flexibility.

In the absence of a commanding authority, tribes, cities and irrigation districts should be empowered to develop and pilot new ways to use the river’s dwindling water supply efficiently.

Tribes and farmers may be able to lease some of their un-needed water to cities or other farmers. Irrigators and cities may adopt voluntary conservation programs that reduce water use to leave water in the river or to provide to other users. Cities may find opportunities to work together, saving water today to create shared supplies for the future.

These tools and others create increased connectivity between people and the river, as well as between communities who rely the river’s waters. Increased collaboration and connectivity can create flexibility that helps the river and its communities adapt in the face of shortages.

Those of us in the business of posing solutions to problems facing the Colorado River call these voluntary agreements between willing parties “water sharing” to emphasize the collaborative spirit behind them.

Nowhere is this spirit more apparent than in Arizona, where competing interests in how water gets stored and used have made it difficult to agree on steps toward ensuring the state has abundant water for the future.

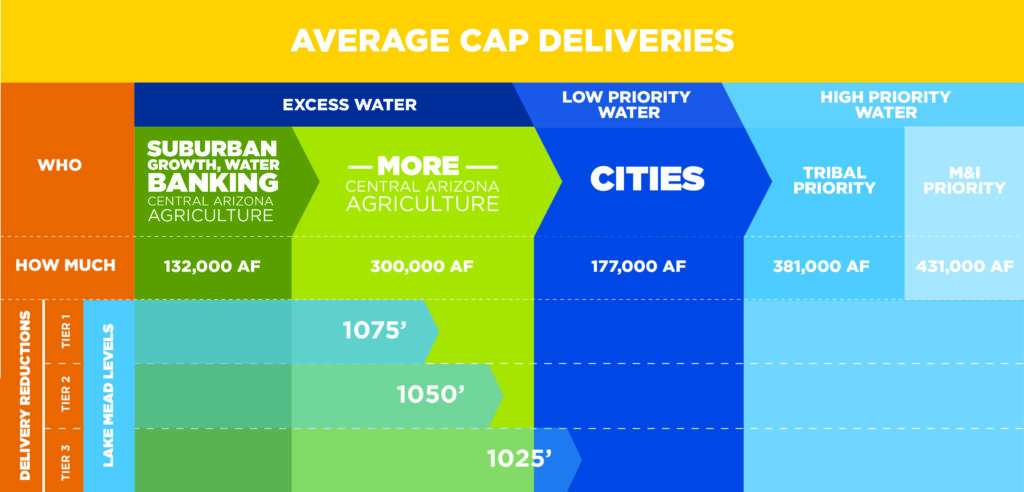

Much of the water for the farms and growing cities in central Arizona is provided by the Central Arizona Project canal, which brings Colorado River water more than 300 miles across the desert before ending near Tucson. Under the Law of the River — the set of compacts and laws that dictate how the Colorado River is managed — this water has some of the lowest priority, meaning it’s the first to get cut back when the river is too low to meet all needs. In central Arizona, irrigators and homebuilders will be the first to feel these cuts, raising questions about unintended impacts. Insecurity in their waters supplies are motivating many cities and irrigators to find creative, collaborative solutions.

Leaders from the Arizona Department of Water Resources and the Central Arizona Water Conservation District have conceptually approved a Drought Contingency Plan with the other six states that rely on water from the Colorado River system, accepting that cuts to Arizona’s water supply are necessary to shore up the Colorado River. However, finding the deals necessary to implement those cutbacks within the community of Arizona water users has been difficult. Some of the more promising responses have flowed (pardon the pun) out of one-on-one, collaborative deals between communities that have water to share and those that are at the greatest risk of suffering shortages in the future.

The cities of Tucson and Phoenix, for example, pioneered a partnership in which Tucson will store some of Phoenix’s water today and provide it back to its northerly neighbor when Phoenix requires water in the future.

Another example: The Gila River Indian Community and the managers of water supply for growing central Arizona communities have crafted an innovative set of short-term water leases and water exchanges that benefit both parties. The deal they have proposed includes swaps of stored groundwater, investments in pumps and canals, and deliveries of some of the community’s currently unused water over a span of 25 years. The innovation and flexibility in this arrangement could take pressure off of other parts of the state’s water supply portfolio, making it easier for all to adjust to a reduced supply.

These kinds of collaboration are necessary if Arizona, and the other river states, are to adapt to long-term changes in the river’s hydrology, and correct the over-allocation built into the Law of the River.

To help illustrate this concept, we’ve posted a short animated video.

When I first floated the idea of a river trip to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, it sounded a lot like the theme song to Gilligan’s Island. There would be a professional fly fishing guide and raft guides, two writers, a photographer, a federal river manager, three conservationists, a world champion free skier and artist, and a longtime American Rivers supporter and his 11-year old son, all traveling together down 30 miles of the Middle Fork Flathead River over the course of five days. Luckily our group would not suffer the same fate as the crew of the S.S. Minnow and get stranded in the wilderness for years. But I bet if you polled the group afterwards, no one would have been particularly bothered by the idea of such an outcome.

Before I started working for American Rivers, I had never heard of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. As a passionate river enthusiast, activist and recreationist, I’m not proud to say that I was completely ignorant of our nation’s strongest river protection law. Having pulled a 180 over the last four years, today my entire world is “wild and scenic.” I immerse myself in Wild and Scenic history, engage in the development of Wild and Scenic management plans, and spend a majority of my waking hours conducting grassroots outreach to built support for more Wild and Scenic river designations in Montana.

Photo by Jeremiah Watt

Naturally when the golden anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act came up this year, I jumped at the opportunity to celebrate. After all, the very idea for the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act was conceived in Montana. Specifically, it was on a multi-day river trip on the Middle Fork Flathead River in the mid 1950s where the idea for a national system of protected rivers was inspired.

Missoula-based wildlife biologists John and Frank Craighead, along with a few colleagues and friends, ventured down the Middle Fork during the summer of 1956 to make a “personal evaluation of its recreational potential,” (Craighead, 1957, p. 16). The Craighead brothers are renowned for their grizzly bear research and for pioneering the use of radio telemetry to track wildlife. When the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers proposed the Spruce Park Dam on the Middle Fork, John and Frank knew that it would flood essential habitat for grizzlies and a myriad of other wildlife species. Determined not to be “obstructionists to development” but rather “defenders of the public interest,” (Craighead, 1957, p. 16) the Craighead brothers set out to identify other important river values that would be negatively impacted by a dam.

In an editorial written in the June 1957 issue of Montana Wildlife, John Craighead described what he observed on his Middle Fork Flathead trip and why he believed it was imperative “to keep intact some wild rivers on the basis that they are essential to our way of life,” (Craighead, 1957, p. 17). He went on to suggest classifications of rivers based on their level of “wildness” due to scale and proximity of development (roads, structures, etc.) Much of what John and his colleagues deliberated while venturing down the Middle Fork Flathead was incorporated into the original Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, which President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law in 1968.

As our group journeyed down this same stretch of river, which looks exactly the same way it did for John and Frank over six decades ago, I was in a state of awe and wonder. Not only because of the overwhelming beauty and untouched wildness of the place, but because of the Craighead brothers’ foresight of preserving wild rivers for the benefit of the public. They knew what they were up against in opposing the Spruce Park Dam, but John pointed out that if an organized system of protected rivers was in place, “competing interests would know where conservationists stand and the people could decide with a minimum of confusion where their interests lay,” (Craighead, 1957, p. 20).

Photo by Jeremiah Watt

Over the last several years, my colleagues and I have been advocating for more Wild and Scenic river designations in Montana. One waterway in particular, East Rosebud Creek, has faced several hydroelectric dam proposals over the last few decades. Consequently, it became our highest priority for immediate protection. Earlier this year the East Rosebud Wild and Scenic Rivers Act was introduced in Congress for the third time. Serendipitously, as our group was absorbing the beauty and wildness of the Middle Fork Flathead River, the East Rosebud bill passed in the House of Representatives, and two weeks later on August 2, it was signed into law. It marked Montana’s first new Wild and Scenic river designation in 42 years.

As our river trip came to an end and our group exchanged heartfelt hugs, there was nothing but gratitude in the air. We were all thankful for our guides, the conversations shared, the opportunity to be in this place together, and ultimately for the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. I asked some of my new friends why this trip was special to them or what it meant to be on the Middle Fork Flathead. The common theme in their responses echoed our mantra at American Rivers – rivers connect us. Much as the Craigheads explained more than six decades ago how rivers connect important pathways for all living things, rivers also bring people from all walks of life together in powerful ways.

This means of connection is what makes me grateful for a system of protected rivers. In many ways this type of public benefit cannot adequately be quantified, but it is still very much observed and felt by those who experience a wild river. If you don’t know what I’m talking about, I encourage you to take a trip on a wild river as soon as you can. Go right now. Then come back and tell all of your friends. Share your river story with the world, or maybe just your local newspaper. Who knows, your story might be the one to protect a wild river forever.

Citations:

Craighead, J. (1957). Wild River. Montana Wildlife: Montana Fish and Game Department Official Publication, 15-20.

#####

Do you have a river story to share? Please visit 5000milesofwild.org today and help us protect more of our most cherished rivers by telling your story.

I know what you’re thinking: It’s been a week since the 2018 midterm elections. Everyone is focused on 2020 presidential election speculation, or the ongoing count/recount drama in Florida, reminding us of the 2000 election that wouldn’t end. So why take a moment to look in the rearview mirror?

It’s only been a week, and the 2018 midterms are still being figured out, but when it comes to rivers, here are three important takeaways:

1) Champions for rivers did very, very well at the ballot box: Montana reelected Senator Jon Tester, who has dedicated his previous two terms to conserving public lands in Montana and elsewhere. Case in point: the successful enactment of legislation to designate East Rosebud Creek as a Wild and Scenic River, which was a true bipartisan effort. Congressman Greg Gianforte (also reelected last week) and Sen. Steve Daines (not on the ballot) were also champions for getting this bill across the finish line.

Another champion for rivers, Senator Maria Cantwell of Washington, was also reelected. Senator Cantwell has championed public lands and rivers from her perch as ranking member of the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, and is the lead sponsor of legislation to enact the landmark Yakima Basin Integrated Plan.

Senator Ben Cardin of Maryland, the foremost defender of the Clean Water Act in the U.S. Senate was reelected by a wide margin. Clean water and rivers have no better friend than Ben Cardin.

2) There are some new sheriffs in town: With the change of party control in the U.S. House of Representatives, there are new Committee chairs overseeing important House Committees who are strong supporters of rivers and the environment.

For example: the incoming Chairman of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, Frank Pallone of New Jersey, has been a steadfast protector of rivers, standing up to the efforts of the National Hydropower Association to weaken the Endangered Species Act and the Clean Water Act.

Incoming Chairman of the House Natural Resources Committee, Raul Grijalva of Arizona, is the foremost defender of endangered species in the Congress. For the next two years at least, we shouldn’t have to worry about the Natural Resources Committee approving bill after bill to deny protections to some of the planet’s most vulnerable fish and wildlife.

It takes funding to protect and preserve public lands, repair outdated water systems, and remove dangerous and outdated dams. Nita Lowey of New York, whose district runs along the lower Hudson River, understands this connection and she will be the Chairwoman of the House Appropriations Committee. That’s the Committee that produces the annual bills that set the spending priorities for the federal government. It’s also the Committee that decides whether harmful riders, like the one this year that tries to block the Clean Water Rule, are attached to annual spending bills.

3) Unfortunately, many Republicans who support the environment retired or were defeated, such as Rep. Carlos Curbelo and Rep. Ileana Ros-Lehtinen of Florida. An exception was in Maryland where Governor Larry Hogan was reelected. Governor Hogan has championed dam removals on the Patapsco River, including the removal of Bloede Dam, and defended the Clean Water Act against attacks by Exelon Corporation and other members of the National Hydropower Association. Rivers are not and should not be a partisan issue, and it’s important to have bipartisan support for river conservation at all levels of government. As Rep. Mark Sanford, a South Carolina Republican, wrote in The New York Times recently, “[T]he environment matters to voters. As a party, we have somehow forgotten that conservatism should apply to more than just financial resources. Being conservative should entail being conservative with natural resources, too.”

What does this mean for American Rivers? We’ll still be here in DC and in our offices across the country, fighting against ill-advised attempts by those in Congress and by President Trump to weaken environmental laws and to slash funding for river conservation. But we’ll have a lot more allies in powerful positions to fend off these attacks, and to ensure that river conservation remains a priority.

We’ll also continue to work as we always have, looking to build bipartisan coalitions for river conservation, just like we did just a few short weeks ago in getting the East Rosebud Creek Wild and Scenic bill and the America’s Water Infrastructure bill enacted into law.

As I write this, the votes haven’t been fully counted in Florida and Georgia, and there’s still a Senate runoff election in Mississippi in December. But it’s already clear that the election of 2018 was a big win for rivers.

Over the last decade, communities across the country have realized that protecting and restoring their local river encourages recreation, creates an economic engine for the region, and strengthens connections across the community. Over the last decade, many communities have changed their outlook on rivers and discovered the many benefits of a healthy ecosystem, including how recreation in river corridors improves and sustains local economies.

Here in Colorado, river related recreation is not only a quality of life benefit but also an economic engine, contributing over nine and a half billion dollars and 80,000 jobs to the state’s economy. Protecting and restoring rivers improves local quality of life by putting people in contact with the outdoors, providing green space, and offering ample opportunities to recreate and move outdoors, while also connecting community members with each other and the local treasures in their city.

Montrose, CO — photo credit to Scott Murphy

The City of Montrose is one of the many Colorado communities who have reconnected with their local river. Earlier this fall, I spent a morning along the Uncompahgre River in Montrose, Colorado talking with city representatives, including City Manager Bill Bell about the importance of the Uncompahgre to their community. Here is what Bell had to say about Montrose’s efforts to connect to its local river:

“The Uncompahgre River flows through the City of Montrose and for many years, the Montrose community had turned its back on the river. Unfortunately, we focused on the river for utilitarian purposes only. That has all changed! Over the past several years, we have changed our focus to highlighting our river as a wonderful natural amenity that helps to foster the Montrose lifestyle based on healthy and active living, as well as outdoor recreation. We not only promote our river corridor as a destination for rafters, kayakers and stand-up paddle boarders, but we also advertise the great fishing opportunities that exist throughout town.”

The Uncompahgre River is now an important corridor for the City of Montrose. Not only does it provide river access for the residents and tourists that come to enjoy the six mile “daily run” on the Uncompahgre, but the river is followed by an amazing bike and walking trail for many to enjoy. The popular walking trail will soon be extended, matched by GOCO dollars, for another 2 miles, connecting the community to their newest river recreation project, the Colorado Outdoors project, a river restoration and multi-use project.

The Colorado Outdoors project is a significant undertaking for the City and its partners, including Mayfly Outdoors, a fly-fishing company helping spearhead the project. Unlike some projects, this public-private partnership to restore over a mile of the Uncompahgre, bring new recreation opportunities including fishing and boating access along with the new walking trail, and improve the local economy has a unified, collaborative vision.

Montrose water sports park: credit Mayfly Outdoors

Montrose, like many other communities in Colorado, understands the importance of a healthy, flowing river for their community. Tune in today to hear more about the City of Montrose’s connection with the Uncompahgre River and the collaborative nature of the river revitalization process.

Ripple Effects is a sub-series of American Rivers’ podcast We Are Rivers. Join us as we explore more Colorado river towns like Montrose, Durango, and Steamboat Springs that have reconnected with their local river and have experienced the ripple effects that only a local river can provide.

You’re not alone if you don’t know what the Southwest’s new drought contingency plan is.

Water can be a wonky business — especially in the seven states (Colorado, Arizona, Nevada, California, Utah, Wyoming, New Mexico) that rely on the Colorado River and its exhausted reservoirs, Lakes Powell and Mead. In its simplest terms, the states agreed on a plan to prevent an immediate water crisis. But it’s so much more complex than that.

We parsed recent news to bring you a roundup of what we think is the best writing about the drought agreement and the issues it addresses — as well as the ones it doesn’t. Here’s what you need to know.

Amid climate and Fed Pressure, Colorado River water managers attempt to chart new course (KUNC)

Luke Runyon explores the pressures climate change and drought are placing on the Southwest’s water supply. He also goes into the basic concepts surrounding states’ voluntarily accepting cuts to water allocations.

Southwest states release Colorado River drought plan; SNWA board to vote in November (Nevada Independent)

More interesting than explaining what’s at stake if Lakes Powell and Mead drop even further is this article’s dive into the politics surrounding the agreement and why it’s taken three years of negotiating to reach a deal.

Colorado River Basin states agree on drought contingency plans (Mohave Daily News)

This straight-forward news piece details the math behind the agreement, including the cutbacks Arizona, California and Nevada face if Lake Mead drops too low.

Western states release proposed Colorado River agreements (Arizona Republic)

In addition to laying out the pros of the new agreement, this article steps back into history to explain how the Colorado River became so leveraged in the first place.

There’s still a ways to go. While the states have reached an agreement between themselves, it’s really more of an “agreement in principle.” The hard steps are yet to come. Arizona and Colorado have to settle the complicated and contentious issues of how their cuts will be implemented by local water users. Arizona’s legislature has to sign off on the state’s internal deal, and finally, an Act of Congress is necessary to settle some of the federal issues involved. None of this is by any means certain.

Of course, truly addressing the challenges facing the Colorado River means coming to grips with three realities:

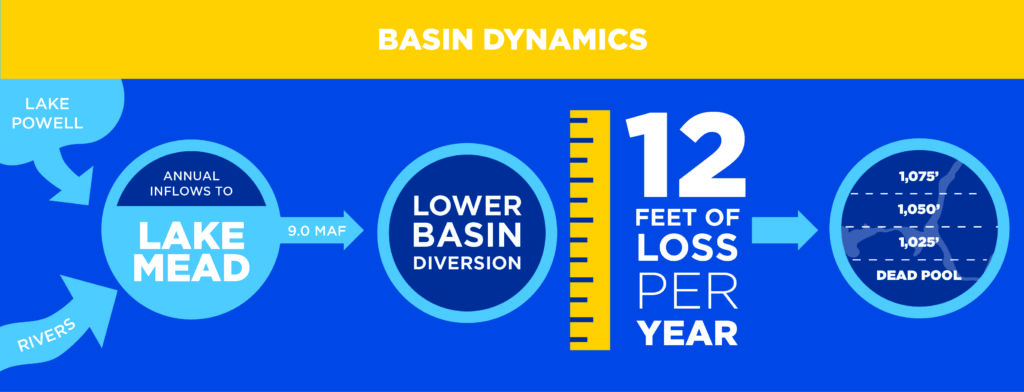

- We take more water out of the Colorado River than what nature can supply.

- The system of allocating Colorado River water to the seven states was broken from the get-go.

- The future of the Southwest is contingent on our ability to use less water and prioritize the health of the river.

Over the past four years, American Rivers has played an important role in efforts to secure Arizona’s water future and protect the Colorado River. Together with a coalition of other state and national organizations, we have brought city and agricultural water leaders together to share ideas and develop common sense solutions. We’ve been a voice for the River and Arizonans in workshops convened by the governor, Arizona Department of Water Resources and the Central Arizona Project. We are working to innovate new methods for using water efficiently and sharing water supplies to create flexibility.

The new drought contingency plan is a good step, but it won’t cure Lake Mead’s dwindling water level and bathtub rings. Adapting to a climate-changed future will require significant steps to reduce demand and to manage the Colorado River’s water more efficiently.

The ominous bathtub rings in Lakes Mead and Powell are evidence of the most serious challenge facing the seven U.S. states that depend on water from the Colorado River. The bands of blanched rock, several stories high, tell the story of the nation’s largest two reservoirs in crisis, and a Colorado River that’s steadily losing its ability to meet all the demands placed upon it.

Falling Lake Mead levels threaten Arizona and California water supply

Earlier this month, after years of fitful effort, state agencies and water providers agreed on a Drought Contingency Plan to deal with the very real possibility of shortages in the water supply provided by the river. This tentative agreement is big step toward slowing the decline of Lake Mead and setting up a future of more sustainable water use in the Colorado River Basin.

On the positive side, the tentative agreement creates a framework to save more water in Lake Mead in coming years and to allocate the supply cutbacks that will accompany the nearly inevitable shortage.

According to the Bureau of Reclamation, the federal agency which oversees management of the river system, there’s a nearly 60 percent chance that a “Tier 1” shortage will be declared in the Lower Basin states (California, Arizona and Nevada) in 2020. The goal of the Drought Contingency Plan is to prevent even deeper cutbacks in the future supply available to the Lower Basin.

Lake Powell: Photo credit Rainer Krienke

A successfully implemented Drought Contingency Plan will reduce the risk of deeper shortages. It is our best chance to avoid significant cuts to Arizona’s water supply.

From the moment a Drought Contingency Plan is formally signed, central Arizona will have to live without 192,000 acre feet of water per year. (One acre foot is enough water to cover a football field 1 foot deep.)

It’s also likely that the federal government will declare a “Tier 1” shortage in 2020, forcing a cutback of 512,000 acre feet of water per year, or nearly 30 percent of Arizona’s annual Central Arizona Project supply. Without an Arizona agreement on how to equitably allocate this cutback, shortages on the river will likely deepen, forcing the state to forego an additional 128,000 acre feet.

Right now, all of this water is used by farms in central Arizona, the new subdivisions sprouting up around the Valley of the Sun, and homes and businesses in cities around Phoenix. Protecting people and farms while securing the future of the river is a difficult challenge and must be done in an equitable way within established laws and priorities.

Looming shortages will cut deeply into water available for Arizona

But the Lower Basin Drought Contingency Plan only gets us so far. It provides the river community with breathing space to tackle the deeper problems facing the Colorado River and its communities — including the original over-allocation of the river’s water; over-consumption by farms and cities in California, Arizona and Nevada; and the intensified aridification of the region caused by climate change.

Ever-shrinking water levels in the Colorado River Basin aren’t short-term hiccups in hydrology and precipitation. They are the inevitable result of long-term forces that will require bold action to alleviate.

A collaborative Drought Contingency Plan reduces risk to Arizona and Colorado River

This month’s agreements will help get river communities through the near-term shortages that seem inevitable, and they are an important first step toward more lasting solutions. In the next few years, river leaders and water managers have an opportunity to build on the Drought Contingency Plan and to think ahead. Protecting the river and the water it provides will require us to develop resilient solutions that reduce water consumption and efficiently share the river’s waters.

On that humid morning on July 1,1999, we knew we were at a turning point for Maine’s Kennebec River. What we didn’t realize was that we were at a turning point for the conservation movement and rivers nationwide.

TV trucks arrived early at the riverfront in Augusta. Boy Scouts sold donuts, and others gave out commemorative t-shirts. The whole community had turned out to witness this historic event: the removal of Edwards Dam.

Twenty years ago, most lawmakers and conservationists viewed removing dams as a radical, pie-in-the-sky idea. But Edwards proved that dam removal is a viable, cost-effective solution — one that can bring significant benefits to the environment, community and economy.

“The Edwards Dam removal propelled a national movement to remove dams that continues to grow stronger every year,” says Brian Graber, senior director of American Rivers’ River Restoration Program. “Dam safety offices, fisheries managers, dam owners and communities are taking a second look at the benefits and impacts of dams. And many are deciding that removal is the best option.”

Edwards Dam had blocked the Kennebec River for 162 years. It had powered local industry since the days of Hawthorne and Thoreau and was part of Augusta’s history and identity.

But it had also taken a serious toll on the health of the river and its fisheries. It changed the very character of the river by degrading habitat and blocking the migration of a number of species — including Atlantic salmon, American shad, blueback herring and alewife — important to commercial and recreational fishermen. Edwards Dam provided only one-tenth of 1 percent of Maine’s power supply. It was clear the dam’s costs outweighed its benefits.

Now the dam was coming down, thanks to years of work by American Rivers, the Natural Resources Council of Maine, the Atlantic Salmon Federation and Trout Unlimited and its Kennebec Valley Chapter. Together, we had intervened in the dam’s relicensing process and advocated for removal. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission ruled in our favor in 1997.

After a series of speeches, Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt and Gov. Angus King rang a bell next to the podium. Then the bells at St. Augustine’s church started tolling.

Bells ring at symbolic moments: births, weddings, funerals. Now, the bells were ringing for the river.

The backhoe began to work. We strained to see across the river; some stood on metal folding chairs. We watched as the yellow machine’s big metal claw slowly dug away at the temporary dirt cofferdam.

We watched and waited. This was before cell phones and social media. Time stood still. We stood shoulder to shoulder, all eyes on the backhoe, suspended in this moment together.

And then, finally, a big muddy gush of water broke through the dam and the crowd erupted in cheers. The river was running free for the first time in 162 years.

Sturgeon, alewife, eagles and osprey rebounded in the Kennebec within a decade. Hikers now explore newly developed trails. And water no longer sits dead and still. The river is alive once again.

Since that day in Augusta, American Rivers has championed hundreds of dam removals. We’ve celebrated some amazing river restoration successes: The Elwha. The White Salmon. The Penobscot.

Most recently we celebrated the blast at Bloede Dam, freeing Maryland’s Patapsco River.

Together with our supporters and partners, we’ve created a river renaissance – a revival of fish and wildlife, free-flowing waters and new opportunities for people to enjoy and connect with their rivers. We’re the lead on many projects, and we also share our experience and expertise with other advocates so they can advance dam removal efforts in their own communities. We provide technical and funding assistance, conduct trainings for new project managers, and share information to strengthen and advance the movement.

And the movement is going strong: More and more outdated dams are coming down every year: 2017 was a record year for dam removal with 86 dams torn down nationwide. All told, our dam removal database includes information on 1,492 dams that have been removed across the country since 1912. Most of those dams (1,275) were removed in the past 30 years.

As American Rivers celebrates the 20th anniversary of the Edwards Dam removal, we’re recommitting ourselves to thinking big, and to making our national river restoration movement even stronger and more effective. Because, let’s face it, there are still tens of thousands of aging dams serving no purpose yet still clogging our nation’s rivers.

There’s something powerful about imagining a better future for your river, and working with your neighbors to make it happen. There’s something inspiring about watching that first rush of water when a dam is breached. There’s something transformational about a community embracing their river’s restoration story as their own.

Dam removal is about unleashing potential. It’s about tapping into the power of a free-flowing river. Edwards Dam was just the beginning.

Will your river be next?

My parents, brother and I used to call Big Snowbird Creek home for weekends at a time. We camped along its banks with my grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins. Our days were spent swimming, fishing, picking blackberries, cooking together, telling stories, riding four-wheelers and bicycles, playing cards when it rained, and shooting off fireworks on the Fourth of July.

As adults, my husband and I make trips back to that place as often as we can. When we hit the gravel road, we both reach to roll down our windows and take in the cool air and smell of the river. That smell floods me with precious memories every time. Instantly, I’m home. Memories like these are why I chose to work for rivers.

Here at American Rivers, we love starting conversations by simply asking, “What is your favorite river?”

This was the topic of the night when supporters of American Rivers, American Whitewater and MountainTrue gathered to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act at New Belgium Brewing in Asheville, North Carolina.

[su_carousel source=”media: 45362,45361,45360,45359,45358,45354″ title=”no” autoplay=”0″]

Around 500 people came together that evening to celebrate rivers and to share their stories with us. Folks showed up eager to talk about their favorite rivers and ready to act to protect them. Activists wrote passionate messages to elected officials, urging them to protect more waterways under the landmark Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. Together, we enjoyed fellowship with river lovers by telling stories about our favorite rivers.

Ask a group of people “what is your favorite river?” And you’ll sometimes hear the same river name. But the story is always different. From serene paddles to whitewater action; from lazy floats to fly-fishing; from riverside hikes to family picnics — rivers are eager to give. We all have connections to rivers and rivers connect us.

During the 50th anniversary year of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, American Rivers has been celebrating how far we have come in safeguarding rivers, and we look ahead as we work to protect 5,000 additional miles. Many of these special places are at risk. Visit 5000Miles.org to tell us your river story and to take action for our wildest, most outstanding rivers.

Thank you to all those who came out in Asheville to celebrate rivers and join us in protecting them.