Meadows play an integral part in the Sierra hydrologic system, which provides more than 60% of California’s developed water supply. Healthy meadows provide a suite of benefits including improved groundwater storage, enhanced water quality, reduced peak flood flows, and critical habitat. It’s estimated that 50% of Sierra meadows are degraded by human impacts, resulting in the loss of these benefits. Momentum around meadow restoration has been growing as legislators, land managers, and the public have recognized the benefits meadows have the potential to provide. In 2014, the Governor prioritized mountain meadows in the California Water Action Plan, as a means to increase groundwater storage and habitat. This, in turn, has fueled federal agencies, local governments, conservation organizations, tribes, and others to take action.

American Rivers California headwaters team is working hard to restore meadows in the Sierra Nevada. Since 2012, we have completed restoration projects on approximately 730 meadow acres and led 16 projects in 11 watersheds across the Sierra. We also published a journal article presenting the effects of restoration on groundwater and streamflow in a recently restored Sierra meadow and have been co-leading a Sierra-wide partnership focused on increasing the pace, scale and efficacy of meadow restoration.

Currently we are partnering with Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks (SEKI) to build momentum around meadow restoration in designated wilderness. Wilderness is federally designated in National Parks, National Forest, and Bureau of Land Management (BLM) land. It covers over 15% of the Sierra Nevada and is

“for the use and enjoyment of the American people in such manner as will leave them unimpaired for future use and enjoyment as wilderness, and so as to provide for the protection of these areas, the preservation of their wilderness character…”

Castle Domes Meadow | Photo by Maiya Greenwood

The heart and soul of wilderness is maintained by strict rules included in the Wilderness Act of 1964, among which are: no permanent or temporary roads, no motor vehicles, no motorized equipment, no motorboats, no landing of aircraft, no other form of mechanical transport, and no structures or installations. The wilderness designation often comes with the misconception that wilderness is inherently pristine, however, these areas were subjected to human influence and degradation in the hundreds of years prior to their designation. For example, although currently protected, many Sierra meadows were subject to a century of overgrazing following the Gold Rush. The meadows in present-day wilderness often exhibit similar degradation as meadows outside of wilderness areas. To date, the majority of meadow restoration projects completed in the Sierra have used techniques that require motorized vehicles and large machinery to move soil and rock. However, these techniques are not directly transferable to wilderness meadows due to the disallowance of motorized vehicles.

This presents a conundrum; people broke the meadows, but the wilderness designation makes it very difficult for us to fix them.

Colby Meadow | Photo by Maiya Greenwood

So, how can we tackle this problem? American Rivers is partnering with Sequoia and Kings Canyon (SEKI) National Park, which is comprised of 93% wilderness. Our project is aimed to address the wilderness restoration conundrum by determining 1) which wilderness meadows are degraded, and 2) what restoration techniques both effectively address meadow degradation and maintain ‘wilderness character’. We addressed the first question by completing a field assessment of 60 wilderness meadows using the Meadow Condition Scorecard, a tool American Rivers developed in partnership with the Forest Service, UC Davis, and others to rapidly evaluate meadow condition and restoration potential. We are currently addressing the second question by completing a restoration project to pilot wilderness friendly techniques at Log Meadow in Sequoia National Park. This meadow is accessible, and outside of designated wilderness. We are piloting these techniques at a non-wilderness meadow so that we can test logistics and efficacy of techniques prior to applying them in remote wilderness areas with more complicated and costly logistics.

The lessons learned at Log meadow, in conjunction with the completed meadow assessments, will lay the groundwork for extensive restoration and protection of degraded wilderness meadows throughout Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. We hope to scale up this approach and inform wilderness meadow restoration efforts in National Parks, National Forests and BLM land across the Sierra Nevada region.

Thanks to our funders: the California Department of Fish and Wildlife and the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation who are supporting this important work.

Communities seeking relief from flooding caused by increasingly intense storms.

Fish seeking refuge from warming downstream waters.

Parents seeking solace when their child has been pulled into the undertow of the base of an artificial waterfall (aka a dam).

Landowners pouring money into failing, obsolete structures, or perhaps pretending they do not exist at all… just waiting for the next big storm to knock them down.

The reality of living in a world with a changing climate is real, and we must ensure that we actively work towards making our rivers and communities more resilient. Now is the time to revive our rivers and streams— the lifeblood of our nation. The good news is that we are making progress.

It has been another successful year of busting dams and reconnecting rivers and streams across America. Every year the dam removal movement continues to grow stronger. In 2018, 82 dams in total were removed from across the country. Communities in 18 states worked closely with various non-profit organizations, local municipalities, state and federal agencies to remove these dams and successfully reconnect more than 1,230 river miles.

Dams were removed in the following states: California, Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

In 2018, California had the highest number of removals, surpassing Pennsylvania, the leading dam removal state for the past 15 years. The top three states removing outdated dams in 2018 were:

- California – 35 dams removed

- Pennsylvania – 7 dams removed

- Michigan – 7 dams removed

Over the years, the number of dam removal projects have continued to increase, with most removals (1,355) occurring over the past 30 years. Pennsylvania has the highest number of removal projects so far (337 total recorded), while other states nationwide are also stepping up to the challenge (this year’s leader, California, has 148 total removals, followed closely by Michigan with 139). From 1912 through 2018, 1,578 dams have been removed in the U.S. to restore fish passage and access to habitat, eliminate safety hazards, and reduce future liability for owners and surrounding communities.

For over a century, the U.S. has led the world in dam building. However, like all infrastructure, dams don’t last forever. Twenty years ago this July, Edwards Dam was removed from the Kennebec River in Maine. It marked the first time the federal government ordered a dam removed because its costs outweighed its benefits; it garnered worldwide attention. The Kennebec is a resounding restoration success story, with millions of fish returning every year. It inspired a movement that continues to grow, nationally and globally.

Today, many local communities have come to understand that while in some situations dams can be beneficial, they can also cause a considerable amount of harm to river ecosystems. The American Society of Civil Engineers gives the nation’s dams a D grade in its report card on the nation’s infrastructure. Therefore, dams that were once the center of communities powering mills or supplying water for some industry are subsequently being removed after wearing down or no longer serving their intended purposes.

This year, American Rivers is applauding the great progress that environmental organizations, local municipalities, state and federal agencies, landowners, and others have made towards reestablishing natural river flow and functions through dam removal. However, we are ready to do more. There are hundreds of thousands, perhaps over a million, more dams out there. Many of them are coming to the end of their useful lives. American Rivers is committed to working with our partners across the country to find ways to increase the number of dams removed each year and empower communities to restore and reconnect their rivers. We cannot do it alone.

Please join us now to help accelerate the dam removal movement!

Things you can do:

- Learn more about the benefits of dam removal

- Talk with others in your community about the benefits of dam removal

- Support the removal of outdated dams within your community

- Comment on this blog post and tell us if you know of possible projects. We will make sure to connect you with an American Rivers staffer in your region or with someone in your local community who may be able to help.

HIGHLIGHTS OF DAM REMOVAL AND RIVER RESTORATION EFFORTS IN 2018 INCLUDE:

Bloede Dam, Patapsco River, Maryland

The Bloede Dam was removed in 2018 as part of a larger plan— which included removal of the Union and Simkins dams in 2010— to restore more than 65 miles of spawning habitat for blueback herring, alewife, American shad, hickory shad, and more than 183 miles for American eel in the Patapsco River watershed. Originally built by a private company in the early 1900s to supply electricity to the cities of Catonsville in Baltimore County and Ellicott City in Howard County, the 34-foot high by 220-foot long dam, located in Patapsco Valley State Park, was most recently owned by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources. At the time of demolition, it no longer produced power or any other economic benefit, but contributed to numerous injuries and deaths, including at least nine dam-related drownings since the 1980s. Its removal reconnects habitat for one of the highest runs of river herring in the Chesapeake Bay.

Contact: Serena McClain, American Rivers, 202-347-7550, smcclain@americanrivers.org

Cleveland National Forest, California

The Cleveland National Forest removed 33 dams in total—18 dams from Holy Jim Creek, four in upper San Juan Creek, 10 in lower San Juan Creek and one from Trabuco Creek—in 2018. The dams were originally constructed for varying uses, including to create pools for a stocked rainbow trout fishery and provide water for fire suppression. However, years of disuse and, in some instances, a 40-year maintenance backlog resulted in the decision to remove these structures as a way to improve stream conditions and provide adequate fish passage and wildlife habitat. The efforts of the Cleveland National Forest demonstrate the power of coupling smart management of outdated water infrastructure with the potential re-establishment of extirpated species like the southern California steelhead trout.

Contact: Kristen Winter, Cleveland National Forest, 858-674-2956, kwinter@fs.fed.us

Columbia Lake Dam, Paulins Kill, New Jersey

The 18-foot tall and 330-foot long Columbia Lake Dam was originally built in 1909 and, at the time of removal, owned by New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection Division of Fish and Wildlife. The project consisted of the removal of Columbia Lake Dam and a downstream remnant dam on Paulins Kill. These two dams were physical barriers to fish migration and negatively impacted river flow. The removal of the Columbia Lake Dam restored access to more than 10 miles of historic habitat for migratory fish including American shad, restored 32 acres of floodplains, and provided safe and new recreational opportunities. The project is anticipated to increase abundance and diversity of macroinvertebrates, including freshwater mussels, that are indicative of good water quality.

Contacts: Laura Craig, American Rivers, 856-786-9000, lcraig@americanrivers.org

Barbara Brummer, The Nature Conservancy, 908-879-7262, bbrummer@tnc.org

To accompany the 2018 list of dams removed, American Rivers updated the interactive map that includes all known dam removals in the United States since 1916. Visit www.AmericanRivers.org/DamRemovalDatabase for more information.

Today the U.S. Senate passed a landmark bill that protects nearly 620 miles of new Wild and Scenic Rivers in seven states, establishes new wilderness areas, protects some important rivers from mining, and reauthorizes the Land and Water Conservation Fund. For Wild and Scenic River designations the bill, S. 47, marks the biggest step forward in nearly a decade.

As we celebrate 50 years of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act this year it is fitting that there is bipartisan support for protecting new Wild and Scenic Rivers from Massachusetts to California, including adding protections for tributaries of the Rogue River, one of the original eight rivers protected in 1968.

Thank you to U.S. Senators Cantwell and Murkowski worked tirelessly to move this massive package of natural resource bills. There are many champions to thank in the Senate for their work on behalf of protecting free-flowing rivers as Wild and Scenic including California Senator Feinstein, Massachusetts Senator Markey, and Senators Merkley and Wyden who fought for 250 miles of new designations in Oregon. With passage of this bill Senator Wyden has now protected more miles of Wild and Scenic Rivers in his home state, over 2000, than any member of Congress ever. Senator Wyden is a true river champion.

The overwhelming local support for these protections are the reason why they are moving through Congress despite the gridlock that usually dominates Congress when it comes to natural resource issues. A special thanks to the years of hard work of groups like the Nashua River Watershed Association, American Whitewater, the Farmington River Watershed Association, Molalla River Alliance, and K.S. Wild to help organize river communities in support of these new designations. Thanks also to our business partners including Northwest Rafting Company, Nite Ize, NRS, REI, OARS and Yeti.

We are hopeful that the House passes this critical bipartisan legislation and send it to the President’s desk for signature.

Some details on the rivers protected:

- 256 miles of new designations the for tributaries for the Rogue River, the Molalla, and Elk Rivers in Oregon;

- 110 miles of the Wood-Pawcatuck Rivers in Rhode Island and Connecticut;

- 76 miles of Amargosa River, Deep Creek, Surprise Canyon and other desert streams in California;

- 63 miles of the Green River in Utah;

- 62 miles of the Farmington River and Salmon Brook in Connecticut;

- 52.8 miles of the Nashua, Squannacook and Nissitissit Rivers in Massachusetts and New Hampshire.

Nashua River | Photo by Nashua River Watershed Association

Along with the designation of East Rosebud Creek in 2018, Montana’s first new Wild and Scenic River in 42 years, today’s action is a major step forward for the 5000 Miles of Wild campaign, an effort led by American Rivers, American Whitewater and our partners to protect 5,000 additional river miles and 1 million acres of riverside by October of 2020.

The bill includes other critical river protection and restoration measures, including:

- Reauthorizing the Land and Water Conservation Fund, the nation’s largest and most important conservation program that provides hundreds of millions of dollars annually to secure the purchase and protection of public lands;

- Wild and Scenic North Umpqua River Wild Steelhead protections: Would protect 99,653 of steelhead habitat in the North Umpqua River watershed in honor of Frank Moore, a World War II veteran and his wife, Jeanne, legendary stewards of the river;

- Mineral withdrawals to protect the Yellowstone River in Montana, the Methow River in Washington and the Wild and Scenic Chetco River in Oregon from harmful mining;

- Name change for Oregon’s Wild and Scenic Whychus Creek, formerly known as Squaw Creek, a derogatory term.

This is a guest blog by Gregory Fitz.

In October of 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act into law. The legislation had been sponsored in Congress by Senator Frank Church of Idaho. The National Wild and Scenic Rivers System was conceived around the remarkable idea that some rivers were so valuable to the cultural and environmental legacy of a region that they should be preserved as natural, free-flowing waterways for the benefit and enjoyment of future generations. Since then, almost 13,000 miles of 208 rivers across the country have been protected. Six of those rivers are in Washington.

To celebrate the 50th Anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, we are spending some time over the course the year telling the stories of Washington’s designated rivers: Illabot Creek, the Klickitat River, the Pratt River, the Skagit River system, the White Salmon River and the Middle Fork of the Snoqualmie River. Each is a unique part of Washington’s astounding network of rivers and each earned its designation in the national system through the hard work and foresight of advocates.

In this third installment of our series, we’ll take a closer look at Washington’s mighty Skagit River system and one of its valuable tributaries, Illabot Creek.

The Skagit River and Illabot Creek

The Skagit River is the largest river in Puget Sound and one of the biggest rivers in the entire state. It runs 150 miles long and drains a mountainous watershed that encompasses almost 1.7 million acres of the North Cascade Range and coastal Washington. The tallest peaks in the basin are a pair of volcanoes, Mount Baker and Glacier Peak. The Skagit River, along with its tributaries the Sauk, Suiattle and Cascade Rivers, were the first rivers in Washington to be included in the National Wild and Scenic River System. They are astounding, archetypical examples of northern rivers.

Eagle Viewing on the Skagit River | Photo by Glen Campbell

The Skagit begins when it first flows off Allison Pass in the Canadian Cascade Mountains of British Columbia. It is joined by three major tributaries – Snass Creek, the Sumallo River and the Klesilkwa River – before it crosses the U.S-Canadian border. Between the border and the town of Newhalem, Wash., the upper river is impounded by the Skagit River Hydroelectric Project. This project consists of three dams owned and operated by Seattle City Light and, as recently as 2012, produces nearly 90 percent of Seattle’s electricity. The section of the Skagit River protected by the National Wild and Scenic River System’s “free flowing” designation begins below the areas impounded by these three dams. The dams were built many years before the National Wild and Scenic River System was passed into law.

The Gorge Dam is the lowest of the three dams in the project. It was originally built between 1921 and 1924. It was replaced by a taller version in 1961. Below the Gorge Dam the river often runs dry as the water is diverted into a tunnel. It re-emerges near the town of Newhalem. Diablo Dam, the middle of the three, was built between 1927 and 1930. The furthest upriver, the Ross Dam, was constructed in three stages. The first was completed in 1940 and the second and third were finished in 1953. All three dams are listed in the National Register of Historic Places. They span a forty-mile length of the upper river and they impound reservoirs that stretch back across the U.S.-Canadian border. They were built without fish ladders. While migratory fish passage is blocked, the flooded geography included a severe gorge that may have prevented large numbers of historic salmon and steelhead populations above the dam sites. This makes the habitat present in lower river tributaries all the more crucial to the Skagit’s fish populations.

The Skagit’s largest tributary, and a substantial river in its own right, the Sauk River, joins it below the town of Rockport, WA. The Suiattle River joins the Sauk north of the town of Darrington. The Cascade River joins the Skagit at the town of Marblemount. The Sauk, Suiattle and Cascade rivers were all included in the original Skagit Wild and Scenic River System when it was designated in 1978. The Baker River, the Skagit’s second largest tributary, joins the Skagit near the town of Concrete, downstream a few miles from its confluence with the Cascade. The Baker River has been impounded by hydroelectric dams since 1925 and was not included in the Skagit’s Wild and Scenic designation, though it is home to a population of genetically distinct sockeye salmon. From there the Skagit flows west another forty miles toward Puget Sound. Not long before reaching saltwater, the huge river splits into a north and south fork, forming Fir Island in the process. The estuary joins Puget Sound at Skagit Bay, 60 miles north of Seattle.

Rafters on the Sauk River Tributary | Photo by Thomas O’Keefe

The Skagit River is named for the Skagit People, two distinct tribes of Lushootseed Native Americans who live in the region. Before European settlers arrived, the Upper Skagit People occupied territory along the Skagit, Baker and Sauk rivers. The Lower Skagit, often called the Whidbey Island Skagits, occupied land on Whidbey Island and near the mouth of the Skagit on the mainland. Today, the Skagit River basin remains home to the Upper Skagit, the Swinomish and Sauk-Suiattle Tribes.

Illabot Creek is a small but significant tributary of the Skagit that joins the river upstream of Rockport. It isn’t one of the largest tributaries, but it still has miles of great salmon, steelhead, bull trout and bald eagle habitat. Where that habitat had been historically compromised, some of the crucial, and ongoing, habitat restoration work occurring in the basin is currently underway. It wasn’t included in the original Wild and Scenic designation for the Skagit System but was added thirty-five years later as its own designation.

Wild and Scenic Rivers Designation

When the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act was originally passed in 1968, the US Forest Service (USFS) (among other agencies and advocacy groups) immediately begin to assemble lists of candidate rivers in Washington state that would meet the eligibility requirements for future designation, as was required by law. Washington is lucky to have a great number of waterways that meet this USFS criteria, but because of its astounding importance to the region, and outstandingly remarkable values (ORVs) including scenic, recreational, wildlife and fisheries, the Skagit River rose to the top of the list.

The Skagit would eventually be included in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System (NWSRS) in November of 1978, a decade after the system was created. It was added as a portion of the National Parks and Recreation Act, a piece of legislation spearheaded by the California Representative Phillip Burton. At the time it was the largest parks bill in history and the Skagit system was the first of its kind to be included in the NWSRS.

During this period that the Skagit River was being considered for designation, another dam and a nuclear power plant were being proposed in the region. The dam would have been the fourth dam in Seattle City Light’s upriver hydroelectric complex along the upper river near Copper Creek. The nuclear power plant was being proposed on Kiket Island, in Skagit Bay. The upstream and downstream boundaries of the Skagit’s main stem designated section was drawn to leave room for both of these power generation facilities, though due to changing economics and growing political opposition, neither was ever built.

Kayaking on the Skagit River | Photo by Thomas O’Keefe

The Skagit River’s addition to the National Wild and Scenic River System also included the Sauk, Suiattle and Cascade Rivers. In total, almost 160 miles of rivers were protected. These important tributaries were designated as scenic rivers and were valued for the crucial fish habitat contained in their watersheds. It was a groundbreaking advancement in the legal protection of rivers to include the remaining, integral tributary habitat as part of one large, interconnected network. It was the first time in the history of the National Wild and Scenic River System that a river was considered as an entire system built around the needs of anadromous fish. The designation recognized and celebrated the way healthy rivers function as a whole and protected much of the remaining, best habitat available.

At the time, Illabot Creek wasn’t included as a part of the Skagit River System’s original Wild and Scenic designation. Advocates and ecologists always recognized its importance to the Skagit’s network of spawning habitat and, eventually, in December of 2014, a little over 14 miles of Illabot Creek was added to the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. This was an important addition to the protected network of tributaries within the Skagit River system, but also evidence of the opportunity to continually expand and protect additional river miles within the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. The law continues to be a fundamental, and evolving, conservation tool fifty years after the original legislation was passed.

The Skagit Wild and Scenic River System and Illabot Creek: Today

It is almost impossible to overestimate the importance of the Skagit River, and the incredible network of rivers in its comprehensive system, to the Puget Sound region of Washington. It is an iconic river of the Pacific Northwest. Its salmon and steelhead are legendary and sustained people in the region for millennia. Those communities were bedrock among the Coastal Salish people.

The basin is a crucial corridor for wildlife migration through the Cascades and is home to one of the largest population of wintering Bald Eagles in the continental United States. The original Wild and Scenic designation celebrated the free-flowing characteristics and clean water quality of the designated watersheds. All of the rivers in the designation, with Illabot Creek being an exception, are important boating rivers. Whitewater rafting is especially popular on the Sauk and Suiattle Rivers. A niche fly-fishing technique involving two-handed rods and short, heavy lines was developed on the Sauk and Skagit by winter steelhead fisherman. All around the world, fly fisherman now cast “Skagit Lines” in pursuit of fish on moving water.

Skagit River Angler | Photo by Luke Kelly

The fish remain fundamental to the watershed. The Skagit system is home to chinook, chum, coho, sockeye and pink salmon. It is synonymous with winter steelhead and its watershed contains one of the healthiest and important populations of bull trout in the Western U.S. But, like the rest of Puget Sound’s rivers, salmon and steelhead populations in the Skagit River are struggling compared to historic returns. The Wild and Scenic River designation protects important spawning and rearing habitat and provides a base for ongoing restoration projects to proceed. Important restoration work is being done on the lower Sauk River, and on the alluvial fan of Illabot Creek. The Skagit River System Cooperative, on behalf of the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community and Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe, along with the Upper Skagit Indian Tribe, Skagit Watershed Council, The Nature Conservancy and The Skagit Land Trust, among others, are working closely with the U.S. Forest Service and the region’s private landowners to foster and support on-going efforts to stabilize and protect the river system’s diminished salmon and steelhead populations.

While pink and chum salmon in the Skagit system seem to be slipping during recent years, winter steelhead and Baker River sockeye salmon have been re-building their diminished numbers. The sockeye travel the Skagit until turning to swim up the Baker. Improved hydropower management and a fish trap-and-haul facility on that river has allowed more fish to reach their spawning habitat. After years and years of collapsing numbers, winter steelhead in the Skagit were listed as an Endangered Species in 2007. The river was closed to fishing soon after and hatchery steelhead were prevented from diluting the wild stock by lawsuits. From a low of approximately 2000 winter steelhead, populations have rebounded to an estimated average of 6000- 8800 steelhead a year. For the first time in a decade, a short catch-and-release winter steelhead season was allowed in the Spring of 2018.

The Skagit River System, with its miles and miles of protected tributaries, remains an ideal place for the essential work of conserving the best remaining available fish and wildlife habitat and the crucial ecosystem functions provided by wild, flowing waterways. It is a beloved river, the lifeblood of the North Puget Sound region since time immemorial, and a perfect example of the priorities and values celebrated by the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System.

Gregory Fitz is a writer, conservationist and fly fisherman based in Seattle.

In our final post, we’ll be profiling the Middle Fork Snoqualmie and Pratt Rivers, two more of the six Wild and Scenic designated rivers in Washington.

In celebration of the 50th Anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, we have teamed up with a number of partners and outdoor gear companies to collect 5,000 wild-river stories and to protect 5,000 more miles of such rivers nationwide. Share your story and learn more.

It takes a village. The first time that I sat down with planners from the Flathead National Forest was six years ago, on a rainy April day in Kalispell, MT. The coffee was warm, the doughnuts were somewhat fresh, and the specialists from the Forest Service were friendly. My friend and I were there to represent a recently formed rivers coalition during the forest plan revision process. This was the first of many such meetings, as well as the beginning of many phone calls and emails from the boaters, anglers, landowners, businesses, agricultural producers, and conservationists that make up our coalition, Montanans for Healthy Rivers. Our goal was to ask the Flathead National Forest to protect a number of key headwaters streams in their Revised Forest Plan as eligible for designation under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act.

Wild and Scenic Eligible Rivers

Rafters on the Middle Fork Flathead | Photo by Mike Fiebig

While many people understand that the 50-year old Wild and Scenic Rivers Act protects some of the best rivers in the U.S. in their free-flowing state, as designated by Congress, few also know that public lands management agencies are required to inventory and protect public lands streams that meet the requirements for designation under the Act. These are called eligible streams. What does it take for a stream to be found eligible, you ask? Just two things: A stream must be free-flowing, and possess at least one “outstandingly remarkable value.” Streams that are found to meet those two conditions are to be protected in their current state for the life of the plan. Simple, right?

Friendly Persistence…

Armed with this knowledge, our scrappy group of river lovers went about showing Forest Service staff, through photos and stories, which rivers have outstanding recreation, fisheries, scenic, wildlife, geology, history and cultural values. It took a lot of bad coffee and tenacity, but in the end it paid off.

Gets Results

On January 28, the Flathead National Forest released its Record of Decision, unveiling the updated Forest Plan that will guide its operations for the next 15-20 years. The new plan protects 22 Wild and Scenic Eligible streams, totaling 284 river miles, as well as the over 90,000 acres of riverside lands surrounding them. Unprotected streams such as the 35-mile long Spotted Bear River and culturally important Trail Creek are now administratively protected from oil and gas development, mining and damming. This is nearly DOUBLE the number of streams that we started with at the beginning of the plan revision process. These streams will now be protected for the life of the plan.

You Can Do This Too

Yakinikak Creek | Photo by Mike Fiebig

Engagement works. It’s also a fun way to get to know your public lands better. Plug into your local Forest Plan or BLM Resource Management Plan Revision and tell agency officials what YOU love about public lands rivers and streams in your area, and which ones you want to see protected. It works. And it takes a village.

In Episode 15 of We Are Rivers, we explore what the Upper Colorado River Basin States are doing to reduce the risk and potential effects of a “Compact Call” in the Upper Basin

We recently released Episode 14 of We Are Rivers featuring Jim Lochhead, CEO of Denver Water and Andy Mueller, General Manager of the Colorado River Water Conservation District. In part 1 of this two-part series we learned what a Colorado River Compact Call is and how it would affect the river and communities that depend on it. Today, we release Episode 15, or part 2 of the series, hearing again from Lochhead and Mueller. This time we hear their thoughts about what the Upper Basin States are doing to reduce the risk of a Compact Call, and the potential ensuing disruption to water supplies, the environment and the economy of the Upper Basin and Colorado River states overall.

As a reminder, a Compact Call on the Colorado River could occur if Upper Basin States are unable to deliver the water they are required to send through Lake Powell under the rules of the 1922 Colorado River Compact to the Lower Basin States. Overuse of water, aridification of the West due to climate change, and growing populations throughout the basin are putting extreme pressure on the Colorado River. To help reduce the risk of a Compact Call, both the Upper and Lower Basin states are negotiating Drought Contingency Plans (DCPs) to deal with the very real possibility of water supply shortages on the Colorado River.

In Episode 15, both Lochhead and Mueller talk about what the Upper Basin states are doing to reduce the risk of a compact call through the Upper Basin DCP. Water managers are taking a number of different voluntary approaches to reduce Compact risk, including demand management, a voluntary program that compensates water users on a temporary and voluntary basis to reduce water use and increase deliveries to Lake Powell. To learn more about demand management, including the benefits for agriculture, the environment and recreation, check out Episode 11 of We Are Rivers.

Demand management is the cornerstone of the Upper Basin states solution in the DCP. However, incentives for water users to conserve water is limited – today there is no way to ensure it stays in Lake Powell until there is a time when a Compact Call may be enacted. However, Upper Basin water managers are looking to change this.

To ensure voluntarily conserved water stays in Lake Powell instead of being depleted by Lower Basin states, Upper Basin water managers are looking to create a dedicated “pool” of conserved water in Lake Powell. The amount of intentionally conserved water would be booked and recorded in Lake Powell and would have to stay in the lake until dry years when the Upper Basin needs to release it to the Lower Basin. (As a reminder, it is only conserved water that we are talking about, other excess water from rain and snow melt wouldn’t be kept in Lake Powell as Upper Basin Water). This extra security would be stored to help curtail a compact call, supporting the conservation efforts of the Upper Basin states.

This is exciting stuff! Tune in today to Episode 15 Colorado River Compact Call Part 2 – Reducing the Risks of a Call!

Please note that throughout this episode all referenced reservoir water levels are specific to the time this episode was recorded during the summer of 2018. For updated reservoir levels, you can directly visit a reservoir’s website.

Guest post by Evan Millsap, from University of Alaska, Fairbanks, Museum of the North, as part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Colville River.

Let’s open with a statement: The Colville River is Alaska’s greatest paleontological treasure. Exposures along the bluffs of the Colville River contain some of the most abundant and diverse fossil assemblages in the world. For over 20 years, paleontologists have been coming to the Colville in search of new species in an attempt to gain insight into life in the ancient Arctic. The sediment near the top of the bluffs are full of bones from extinct species of mammoths, whales, and walruses; but the underlying Prince Creek Formation contains fossils that are even more exciting: Alaskan dinosaurs.

Rock with dinosaur tracks taken from the Colville River | Photo by J.P. Cavigelli

Over fourteen new species of dinosaur have been discovered in the North Slope alongside three new species of dinosaur-era mammals. Every summer, as researchers come back to the Colville, they find more and more fossils that were previously overlooked. Most interestingly, these species are significantly different from dinosaurs found in other places. Some paleontologists now refer to the Colville area as a unique “biogeographic province,” with extinct animals unlike anywhere else in the world.

The North Slope in the age of the dinosaurs truly was remarkable. Due to the movement of Earth’s tectonic plates, it was even further north than it is today, and although the world generally was somewhat warmer, the Slope was still the coldest place in the world where dinosaurs lived (that we know of). The Alaskan dinosaurs in this area would have had to put up with 120 days of pure darkness, snow, and temperatures well below freezing. Paleontologists and geologists are still unraveling the puzzle, trying to figure out how they managed to survive in these conditions, what they ate, and how they stayed warm.

Alaska is a tough environment to do research in, and little paleontology is done here compared to other states. However, of the Alaskan dinosaurs that have been officially named, all of them come from the North Slope. Nanuqsaurus hoglandi was a ferocious, cold-hearty, meat eater and a distant cousin to T. Rex. Pachyrhinosaurus perotorum was a tough, brutish, herbivore with a giant boss, or frill, radiating out from its forehead.

Dinosaur mounts from UAF Museum of the North | Photo with permission from UAF Museum of the North

Ugrunaaluk kuukpikensis, the famous dinosaur with a mouth like a duck-bill, has perhaps been studied and debated more than any other Alaskan dinosaur. For years, arguments centered around Ugrunaaluk’s winter habits, as many paleontologists believed these animals could not have survived the harsh climate and must have migrated vast distances just as modern caribou do. However, new detailed analyses of Ugrunaaluk’s bones reveal that this animal probably slowed growth during the winter and did not migrate very far, if at all. Ugrunaaluk must have been a common sight, as this species was an abundant, year-round resident. Ugrunaaluk fossils often weather out of the bluffs along the river and are found scattered along the beaches. More bones of this animal have been excavated than any other Alaskan species. It is truly the iconic Alaskan dinosaur, and is mounted proudly on display at the University of Alaska Museum of the North beneath a painting of the ancient North Slope and an aurora-lit sky.

It seems all too appropriate, then, that the iconic dinosaur of Alaska is named after the beautiful Colville, one of Alaska’s greatest rivers: in Iñupiat Ugrunaaluk kuukpikensis means “ancient grazer of the Colville River.”

Evan Millsap is a PH.D. student at University of Alaska, Fairbanks

Guest post by David Krause at The Wilderness Society, who is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Colville River.

Colville River | Photo by The Wilderness Society

Earlier this year, American Rivers released its 2018 America’s Most Endangered Rivers® report, which included Alaska’s Colville River, or Kuukpik in the Iñupiaq language. This remote Arctic river is one of the wildest in the country. The river’s high bluffs provide nesting habitat for an extremely high numbers of raptors, particularly peregrine falcons, rough-legged hawks and gyrfalcons. Numerous species of fish, including Arctic grayling, salmon and broad whitefish, utilize the watershed during various life stages.

To Arctic residents, the river is an important transportation route to access subsistence resources and culturally important sites. Because of the significance of these values, the Bureau of Land Management established the Colville River Special Area more than 40 years ago.

To the west of the Colville River in the Western Arctic is the remarkable (but very poorly named) National Petroleum Reserve – Alaska (NPR-A). This landscape’s name is a relic of an earlier time and not representative of its extraordinary ecological values and cultural importance. The NPR-A contains two caribou herds as well as large numbers of bears, wolves, wolverines, moose and other wildlife. This area also includes the Teshekpuk Lake Special Area, one of the largest and most unique wetland complexes in the circumpolar Arctic.

Millions of birds migrate to this region every year to breed, raise their young, and molt. This treasured ecosystem, however, is facing significant, near-term degradation by industry and is threatened by shortsighted land use planning on the part of the Trump Administration.

Colville River Map | Provided by The Wilderness Society

Only a few years ago, in 2013, a comprehensive, science-based plan was developed to allow for some oil development within the region while protecting special natural areas of high conservation value. Since then, however, industry has failed to meaningfully offset the impacts of their projects and has irreversibly compromised subsistence use areas of local residents.

This month, the Trump Administration announced that it is beginning a formal process to dismantle the 2013 land management plan, which allowed oil and gas leasing in a little over half of the NPR-A. The Administration’s move to revise the plan will likely remove conservation protections for the remaining area, resulting in leasing and oil development in previously closed areas.

David Krause is the Arctic Lands Conservation Specialist with The Wilderness Society.

You never know what you’re going to find in a river. All too often, tires and metal scraps are more abundant than fish and water plants.

So when a colleague and I arrived at the Mayors’ Grand River Cleanup — the largest river cleanup event in west Michigan — we weren’t sure what we’d find.

For the last 15 years, the West Michigan Environmental Action Council in Grand Rapids, Michigan, has hosted the event, which attracts volunteers from four cities who come to pick up trash along 30 miles of the Grand River.

Although it was sunny, the morning was brisk, and we were relieved to be greeted with smiling faces, coffee and doughnuts. Alongside 1,200 volunteers, our partners at West Michigan Environmental Action Council, and National River Cleanup® sponsor Cascade Blonde American Whiskey, we spent the morning roaming the banks of the river, depositing trash and recyclables in our big clear and black bags.

Cascade Blond Grand Rapids river clean-up | Photo by Ashley Avila

A very large cleanup event, like the Major’s Grand River Cleanup, can’t be accomplished without the help of local site leaders, who instructed us on safety and how to avoid plants such as poison ivy. Along the river banks, we took pictures of items too difficult or unsafe to carry out. (Think water-logged child car seats and half-buried pieces of metal.) The City Sanitary Department would come by later to remove them.

On our arrival back at Sixth Street Park, we enjoyed lunch, live music and refreshments courtesy of Founders Brewery and Cascade Blonde American Whiskey, while connecting about our strange river findings. All told, we removed approximately 20,000 pounds of trash and recyclables from the Grand River that day, proving the event’s motto: “Small acts have grand impacts” on the river.

That is not the only event in Grand Rapids that puts recycling first, though.

American Rivers also partnered with the West Michigan Environmental Action Council and the city of Grand Rapids to encourage recycling at the famed Art Prize.

For 19 days, artists and spectators from around the world vote on their favorite art, which is exhibited throughout downtown Grand Rapids. The free event attracts more than 500,000 visitors, a thousand works of art and artists from 40 countries. It also accumulates tons of trash. To help cut down on trash, American Rivers staff and friends stood at the trash-sorting stations in downtown, and instructed event attendees on which container their trash, recyclables and food waste could go in.

We also separated our deposit cans out of the recyclables for the homeless that collect them to return to stores for bottle deposits. People from all over the world left Grand Rapids with inspiring pictures of art and — importantly — less trash.

Grand Rapids river clean-up | Photo by Ashley Avila

At American Rivers, we help communities protect their rivers — and that includes being an active participant in the cities and towns in which we live. Lucky for us, supporting a local environmental initiative often comes with great perks like music, food and art.

- Organize a cleanup with National River Cleanup®, or sign up for an existing cleanup near you

- Learn more about recycling with our National River Cleanup® recycling guide

- Take our River Cleanup Pledge to pick up trash and help us fill our virtual landfill

- And more!

In mid-December, stakeholders from across the Colorado River basin gathered in Las Vegas for the annual Colorado River Water Users Association (CRUWA) conference to discuss the future across the basin. Every year, important information about the Colorado River is discussed in Vegas, but this year’s conference was particularly important. The seven states that comprise the Colorado Basin have been negotiating Drought Contingency Plans (one for the Upper Basin and one for the Lower Basin) to deal with the very real possibility of water supply shortages from the Colorado River. At CRUWA, the Upper Basin States of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming agreed to move forward toward the completion of a Drought Contingency Plan (DCP,) as did the Lower Basin States of Arizona, California and Nevada.

The driving force behind the interstate Upper Basin DCP is the need to reduce the increasing risk of a compact driven curtailment, or “Compact Call” which could cut water to users across the Upper Basin States. A compact call would occur if the Upper Basin States are unable to deliver the water they are required to send through Lake Powell under the rules of the 1922 Colorado River Compact to the Lower Basin States. Overuse of water, aridification of the West due to climate change, and growing populations throughout the basin are putting extreme pressure on the Colorado River.

The DCP is a critical step for the Upper Basin to secure reliable water for agriculture, cities, industry, and the environment and to avoid the disruption and chaos that would follow a compact call. To learn more about what curtailment means for people and the environment, how it could happen, and why the DCP is so important – please listen as Jim Lochhead, CEO of Denver Water and Andy Mueller, General Manager of the Colorado River Conservation District, discuss what it could mean for Colorado.

Listen today to Colorado River Compact Call Part 1 – What Could a Call Mean; and stay tuned for the second part in the series, Colorado River Compact Call Part 2 – How Can We Mitigate Risks, discussing how the Upper Basin states are working together to reduce the possibility of a compact call.

Please note that throughout this episode all referenced reservoir water levels are specific to the time this episode was recorded during the summer of 2018. For updated reservoir levels, you can directly visit a reservoir’s website.

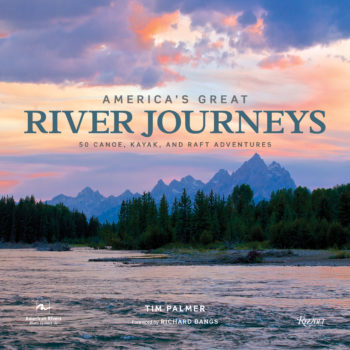

This is a guest post by Tim Palmer, award-winning author of 19 books about rivers, conservation, and adventure travel, including America’s Great River Journeys.

The old adage is true: we only protect what we love, and we only love what we know. So getting to know rivers is important.

There are lots of ways to do that—from simply reading a story or seeing a picture to actually living near the water’s edge—and they can all be satisfying, reveling, and compelling. But going there, floating with the current, and traveling wherever the river takes us may be the best way to know the wonders of our waters and to appreciate the values they offer to all of us.

I’ll go a step further: river trips are among the best things in life.

Rivers wind and plunge as pathways of adventure, of exploration, and of nature, and river trips offer a view that we just don’t get through the windshield. You have to go!

Drifting with the current draws us into the unknown—an incredibly beautiful unknown. Both the serenity of mirroring pools and the rush of explosive rapids stir the body, the psyche, and the spirit.

Part of the fascination for river trips comes simply from the joy that they offer to all. And it’s not just about us. Rivers are home to fish and wildlife, and in traveling on these waterways we can see that they intertwine whole landscapes, regions, and states.

Rivers cool us on hot days, they take us to enchanting places, and in quiet moments they instill or stir thoughts that probe to the core of vital experience, meanings, and mysteries.

Let gravity do the work on the river of our choice! Easily taken for granted, our floating on the current is a pleasure unlike any other. We drift without effort, as if airborne in slow motion flight above the rocks and terrain beneath us. This can be done in utter silence and relaxation as we watch the river bottom and shorelines go by, and there’s something special and serene about doing that for not just a moment or an hour, but for days.

Rivers deliver us to both rugged canyons and scenic valleys, to wilderness that’s untouched and also to the nation’s esteemed heritage of historic landmarks. In their timelessness, the currents of today can take us back in time. On the water and away from the road, we can imagine the past by following the paths of Native Americans and the explorations of Lewis and Clark.

River trips offer visions not just to the past and present, but also to the future. A fate without strong connections and visceral attachments to the natural world would be doomed. By joining the flow and appreciating its beauty, we make those connections. We embrace those attachments.

River trips are microcosms of life itself with its mix of security and risks, comforts and hardships, escapes and returns. These trips are something we can do with family, friends, like-minded people, total strangers, and all the above. Being out there, and connected in a common endeavor, we work together, share the duties and rewards, and get to know each other under conditions that not only allow, but require it.

Rivers come from mountain or upland sources and they swell to grand finales at the edge of the sea. In between—if we’re willing to go—they sweep us up in journeys to the heart of America.

— Published in association with American Rivers, Tim Palmer’s new book, America’s Great River Journeys, features 50 of the finest river trips in America.

— Published in association with American Rivers, Tim Palmer’s new book, America’s Great River Journeys, features 50 of the finest river trips in America.

See it at www.timpalmer.org, or at www.rizzoliusa.com/book/9780847861736.

Here’s what American Rivers President Bob Irvin said about America’s Great River Journeys:

“Tim Palmer’s narratives and photos capture the allure of free-flowing water and illuminate the importance of rivers in our lives. There’s nothing quite like a river trip if you’re searching for adventure, connection with friends and family, and discovering the very best of America’s natural treasures. Sign me up for any one of the fifty magnificent journeys that Tim so well describes.”

Guest post by Save the Boundary Waters is a part of our America’s Most Endangered Rivers® series spotlighting the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness.

The Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness is a vast network of waterways including the Kawishiwi River in Northeastern Minnesota. The South Kawishiwi River is currently threatened by sulfide-ore copper mining from Twin Metals Minnesota on the very edge of the Boundary Waters.

The Boundary Waters

The Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness is the most visited wilderness in the National Wilderness Preservation System. This glacially carved landscape attracts over 155,000 visitors each year for its world-class paddling, fishing, hiking, camping, wildlife viewing and incredible scenery. The Boundary Waters is made up of unique rock formations, expansive boreal forests, and a vast network of clean lakes and rivers to paddle through and portage to. It has 1,200 miles of canoe and kayak routes, 237.5 miles of overnight hiking trails and 2,000 designated campsites.

Mining Threat

The South Kawishiwi River is an important gateway into the Boundary Waters. It flows through the heart of the Wilderness and has three popular entry points for paddlers. The river flows outside of the Wilderness through Birch Lake, re-enters the Boundary Waters downstream, and then flows into Voyageurs National Park and Ontario’s Quetico Park.

Twin Metals Minnesota has proposed a sulfide-ore copper mine along the South Kawishiwi River and Birch Lake. Toxic pollution from sulfide-ore copper mining could drain into and permanently pollute lakes and rivers in the Boundary Waters for hundreds of years, disrupting the surrounding ecosystem. This risky type of mining has never been done in the state of Minnesota, and has never been done safely. Byproducts of sulfide-ore copper mining include hazardous pollutants such as sulfuric acid and other heavy metals, which are harmful to wildlife and people, and could have devastating impacts to the Boundary Waters.

Recent News

This year, we are celebrating the 40th anniversary of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness Act. On October 21, 1978, Jimmy Carter signed the act into law, protecting 1.1 million acres of interconnected lakes and rivers, uninterrupted forests and diverse wildlife. To celebrate this milestone, Minnesota’s Governor Mark Dayton proclaimed October 21, 2018, as Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness Day.

Unfortunately, the Trump Administration recently opened up the Superior National Forest to foreign mining companies, ignoring facts and science. On September 6, 2018, Administration officials announced that the application for a mining ban, which would have protected Northeastern Minnesota’s pristine lakes and rivers from copper-nickel mining, was cancelled. The Administration did not complete a promised study on the social, economic and environmental harm that sulfide-ore copper mining would do to the Wilderness. There is no indication the required environmental assessment was ever completed nor was it ever put out for public comment, which is normal practice.

The Boundary Waters is a national icon that has some of the cleanest water in the world. The Wilderness is major economic driver for Northern Minnesota. The cancelled environmental study would have analyzed the threats and costs to the community posed by sulfide-ore copper mining on the edge of the wilderness.

We must continue to put pressure on the Trump Administration and Congress to protect the Boundary Waters so that all can continue to enjoy this special, wild place.

The Campaign to Save the Boundary Waters was organized by local residents in and around Ely, Minnesota, who are dedicated to creating a national movement to protect the clean water, clean air and forest landscape of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness and its watershed from toxic pollution caused by mining copper, nickel and other metals from sulfide-bearing ore.